1. INTRODUCTION

The association between economic performance and the quality of institutions has been stressed by New Institutional Economics (hereafter NIE). According to NIE, institutions work as «the rules of the game in a society», altering individual incentives and the process of economic decision-making, which, in turn, leads to the development or stagnation of markets (North Reference North1990). Sustained economic growth results from the creation of an efficient economic organisation that protects ordinary people from both predatory rulers and the unilateral alteration of contracts (North Reference North1981).

Early modern Spain has traditionally been portrayed as the stereotype of a country that suffered economic backwardness due to its inefficient economic organisation. Spain, the argument goes, was unable to create either a political framework that limited the arbitrariness of the royal powers or an effective legal system that avoided breaches of contracts.Footnote 1 Some authors have dismissed the notion that Spanish rulers were politically unconstrained.Footnote 2 Yet research on the capacity of the state to guarantee contractual compliance between private parties is much less developed.Footnote 3

Certainly, some economists consider that the influence of formal contracting institutions on long-term economic growth is less important than the role played by those institutions that constrain government.Footnote 4 However, the impact of the legal system on the development of markets through the emergence of a low transaction cost environment has been widely recognised by many scholars.Footnote 5

Public registries—land, companies and credit registries—are among the most important contracting institutions. Well-designed public registries support impersonal exchanges by reducing transaction costs and reinforcing property rights (Arruñada Reference Arruñada2012). As for land registries, they provide creditors with information about a debtor's collateral (ex ante) and accelerate the judicial process after a default (ex post). Recently, some economic historians have tried to measure the effects of registration systems in mortgage markets during the medieval and early modern periods. Van Zanden et al. (Reference Van Zanden, Zuijderduijn and De Moor2012) and Van Bochove et al. (Reference Van Bochove, Deneweth and Zuijderduijn2015) show that the early registration of real estate and land transactions was crucial for the Low Countries' ability to create efficient credit markets earlier than other countries such as England. In addition, they claim that the success of these institutions can only be explained by their interaction with the legal system—mainly mortgage law—the diffusion of collateral and the role of financial intermediaries.

Building on this literature, this article analyses the impact of a specific public registry—the public mortgage registry—on Spanish notarial credit markets at the end of the early modern period. During this period, in the absence of modern banks, other financial actors emerged. Short-term credit was mainly provided by philanthropic institutions (pósitos, montes de piedad or montes píos) and merchants, whereas ecclesiastical institutions dominated the long-term credit market.Footnote 6 With respect to non-philanthropic loans, although these transactions could be agreed orally or through private documents, their notarisation provided a higher level of security.Footnote 7 In Spain, from 1768, this system was reinforced through the establishment of a network of public mortgage registries around the country.Footnote 8 Private parties were theoretically obliged to register those notarial contracts that included some specific assets as collateral, thereby clarifying property rights and reducing and expediting litigation.

Although public mortgage registries have been dismissed as insufficient for their purposes—due to non-observance of the law and their poor design—this article claims that this institution favoured the development of Spanish credit markets.Footnote 9 To test this hypothesis, I draw on a database of almost 2,500 short-term credit contracts (obligaciones) recorded by notaries in the city of Malaga before and after the creation of the public mortgage registry in 1768. By examining special mortgage and general mortgage contracts in Malaga in 1764 and 1784, I show that the creation of public mortgage registries had important consequences for the allocation of credit resources.Footnote 10 After 1768, special mortgage contracts started receiving much higher amounts than general mortgage contracts, whereas before the creation of public mortgage registries, both types had received similar amounts. Furthermore, this institution could have contributed to the development of more impersonal credit markets. Before the creation of the registry, some debtors were able to obtain larger loans thanks to their status, but other debtors lacked the alternatives allowing them to arrive at similar arrangements. After the creation of the registry, debtors could partially solve this problem and obtain more capital in the absence of such a signalling mechanism.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. In the following section, I describe the creation of public mortgage registries in Spain, focusing on their objectives, their problems and their fees. In section 3, I describe my sources. In section 4, I analyse the impact of public mortgage registries on Malaga's notarial credit market. Finally, section 5 presents the main conclusions.

2. PUBLIC MORTGAGE REGISTRIES IN EARLY MODERN SPAIN

In 1768, King Charles III promulgated a law that mandated the creation of public mortgage registries (oficios de hipotecas) across Spain (except in Navarre).Footnote 11 This law made it compulsory to register those new notarial contracts that incorporated a mortgage on a specific piece of land or real estate, an office or an annuity.Footnote 12 Mortgage registries were created mainly to avoid stellionatus, the fraudulent selling or mortgaging of encumbered and mortgaged properties as if they were free (Porras Arboledas Reference Porras Arboledas2004). The authorities wanted to create a network of local registries that gathered together all the information about mortgaged and encumbered properties. With this aim, a registry was created in each judicial district (partido/corregimiento). The registry was located in the town hall of the capital of the district, and the oldest town hall notary in the city controlled it. In addition, the high courts of justice (chancillerías and audiencias) were authorised to create new registries in other municipalities. After formalising a contract, private parties had to go to the registry where the mortgaged property was located and show a copy of the original document. The registrar would then annotate the mortgage. In the event of a default and a judicial process, this annotation would constitute proof of the property. Furthermore, unregistered mortgages did not have legal validity.Footnote 13

The creation and diffusion of mortgage registries in early modern Spain was not an easy process. In fact, prior to 1768, the Habsburg and Bourbon dynasties had both tried unsuccessfully to create similar institutions, initially for annuity contracts, and later for all the contracts that included special mortgages (Table 1). The explanation for this failure is twofold. First, the ambiguity of these laws created many problems related to terms, sanctions, the organisation of the registry and procedures (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, pp. 229-233). Second, these laws were systematically broken by the courts of justice accepting non-registered contracts as proof; by private parties hiding annuity contracts in order to avoid the payment of taxes, and also because they refused to give information about their debts;Footnote 14 by notaries who feared the loss of attributions; and especially by municipalities, as control of the registries generated constant friction when the monarchy started to privatise the offices of registrars instead of retaining them in the hands of the town hall notaries, who were under the rule of the aldermen (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, pp. 229-243; Fiestas Loza Reference Fiestas Loza1998, pp. 31-56).

TABLE 1. IMPORTANT EVENTS IN MORTGAGE REGISTRATION LEGISLATION BEFORE 1768

Sources: Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España, Libro X, Título XVI, Leyes I-II (1805, pp. 105-106), Serna Vallejo (Reference Serna Vallejo1995, pp. 224-262 and 270-283), and Fiestas Loza (Reference Fiestas Loza1998, pp. 31-56).

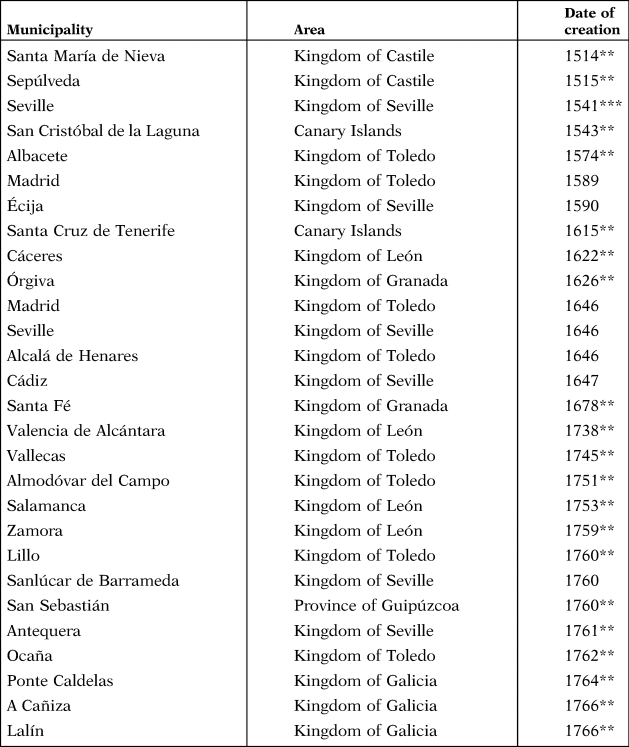

What, then, explains the relative success of the 1768 reform?Footnote 15 Certainly, this law was less ambiguous than its predecessors.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, I suggest that at least two other reasons were relevant. On the one hand, the monarchy finally accepted the transfer of all register attributions for annuities as well as for the rest of special mortgage contracts to a single public institution ruled by the oldest town hall notaries, and ultimately by the aldermen of the municipalities.Footnote 17 With this change, the political elites of the main cities not only gained control of the offices, but also prevented—or at least obstructed—the creation of a property tax. This made economic agents more willing to register their mortgages. On the other hand, since the middle of the18th century, in a context of economic recovery (Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura Reference Álvarez-Nogal and Prados De La Escosura2013), the authorities understood that accelerating the circulation of property required that buyers and creditors could easily obtain annuities and mortgage information on a property (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, p. 217). Authors such as Vizcaíno Pérez, who worked as Lawyer of the Royal Councils, remarked on the legal problems caused by the huge number of properties encumbered with annuities.Footnote 18 In meetings of creditors, annuities' unpaid interest had preference of payment over other credit modalities (Vízcaino Pérez Reference Vizcaíno Pérez1766, pp. 71-74).Footnote 19 This reduced the ability of other creditors to recover their capital, which made them particularly interested in knowing the situation of their potential debtors to avoid stellionatus. With this aim, the monarchy introduced several reforms, including the redemption of annuities or the creation of the public mortgage registries (Peset Reference Peset1982). This need was also perceived by the municipalities, and in fact, from the middle of the 18th century until the 1768 law, increasing numbers of them created mortgages registries (Appendix 1).

Nevertheless, although the creation of public mortgage registries was crucial to strengthening the property rights of owners of both land and capital in Spain, this institution still had many problems. Some courts continued to accept non-registered special mortgages as proof (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, pp. 364-365), many individuals did not register their mortgages, so the terms for doing so were extended (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, p. 279), and the organisation of the registry's book was still problematic (Villalón Barragán Reference Villalón Barragán and Congost2008, p. 242). However, probably the most important problem was that the law did not introduce any of the principles of modern mortgage law: publicity, speciality and priority (Ribalta Haro Reference Ribalta Haro, De Dios, Infante, Robledo and Torijano2007, pp. 304-342). In line with Roman legal tradition, private titling prevailed (Arruñada Reference Arruñada2012, p. 45), general mortgages were maintained (Ribalta Haro Reference Ribalta Haro, De Dios, Infante, Robledo and Torijano2007, pp. 304-342), and the reform did not alter the antiquity principle: except in the case of privileged mortgages, old mortgages always had priority over new ones regardless of whether they were general or special mortgages (Febrero 1786, p. 665).Footnote 20 These problems have led many legal historians to argue that mortgage registries were clearly insufficient to guarantee the protection of property rights.Footnote 21 According to them, legal conditions did not favour the development of credit markets until the enactment of the Spanish Mortgage Law in 1861 and a later reform in 1869 (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, pp. 436-524).Footnote 22

Before measuring the effects of mortgage registries on early modern Spanish credit markets, a last legal aspect must be analysed: the cost of registering a mortgage. Registry fees have been considered a key factor in the success or failure of public registries. If they are high, they create an entry barrier, and, consequently, the role of the registry is severely damaged (Djankov et al. Reference Djankov, La Porta, López-De-silanes and Shleifer2002). However, this position has been criticised by other authors such as Arruñada (Reference Arruñada2007), for whom this approach only takes into account the initial costs and compulsory formalities, and disregards ex post costs, such as court fees or the time needed to foreclose a mortgage, voluntary but common formalities and the quality of the information provided by the institution.

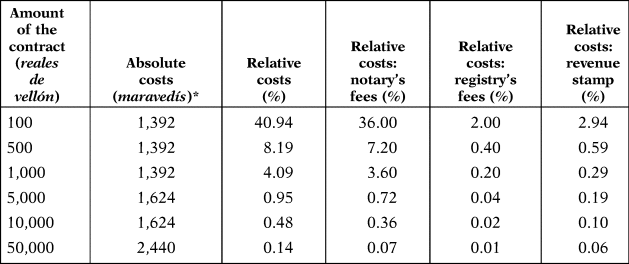

I have calculated the amount of notarial and registration fees for several mortgage contracts worth between 100 and 50,000 reales de vellón (hereafter r.v.).Footnote 23 These prices are calculated for a two-page mortgage obligation contract, the commonest credit contract in Malaga at the time (Table 2). Although notarial fees were high for small contracts, registry fees were always low, including those of small contracts.Footnote 24 I have also compared the costs of the Spanish public mortgage registries with the costs of similar institutions in England (deed registries) and in the Low Countries (real estate transaction registries) in the 18th century.Footnote 25 I use the number of daily wages of an unskilled urban labourer as a reference: data for England and the Low Countries are from Van Bochove et al. (Reference Van Bochove, Deneweth and Zuijderduijn2015), and I have included data on the wages of unskilled urban labourers (peones) in Madrid and unskilled rural labourers (jornaleros) in Malaga during the same period (Table 3).Footnote 26 This shows that the costs, in terms of daily wages, of registration in Spain were quite similar to real tariffs in Dutch municipalities—especially for reduced deeds—and were much cheaper than in England.

TABLE 2. LEGAL COSTS AND TAXES ASSOCIATED WITH A TWO-PAGE MORTGAGE OBLIGATION CONTRACT

*Note: 1 real de vellón = 34 maravedís.

Sources: Febrero (1783, p. 410), Martínez Salazar (1789, p. 285), Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España, Libro X, Título XVI, Ley III, and Título XXIV, Ley X (1805, pp. 108 and 158, respectively), and Moranchel Pocaterra (Reference Moranchel Pocaterra and Sánchez-Arcilla Bernal (PI)2012, p. 737).

TABLE 3. REGISTRATION COSTS IN DIFFERENT EUROPEAN MUNICIPALITIES IN THE 18TH CENTURY. EQUIVALENT VALUE: NUMBER OF DAYS' WAGES OF AN UNSKILLED WORKER

*Note: the Spanish registries did not use the number of words to establish fees, but the number of pages. As each page included approximately 500 words, I have used this as a reference.

Sources: for Spanish municipalities, author's elaboration based on Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España, Libro X, Título XVI, Ley III (1805, p. 108), Villar García (Reference Villar García1982, p. 152), Pinto Crespo and Madrazo Madrazo (Reference Pinto Crespo and Madrazo Madrazo1995, p. 203), and Moranchel Pocaterra (Reference Moranchel Pocaterra and Sánchez-Arcilla Bernal (PI)2012, p. 737); for Dutch and English municipalities, see Van Bochove et al. (Reference Van Bochove, Deneweth and Zuijderduijn2015, pp. 16 and 26, respectively).

Two caveats must be made here, however. First, notaries might have not complied with the law, charging higher tariffs to their customers. Second, registration required additional costs that are difficult to estimate. Before accepting a property as a guarantee, the lender probably asked the notary to examine the debtor's property titles. Although the 1782 official fees fixed a fee for that work (Martínez Salazar 1789, p. 285), it is possible that some lenders demanded additional work from the notaries, especially in the earlier stages of the registries, in return for higher and non-regulated payments.

3. ANALYSIS OF THE DATABASE

To check whether or not the 1768 reform improved the quality of the legal framework, it is necessary to measure its impact on the credit market. With this aim, I have taken notarial credit data from the city of Malaga. In early modern Spain, as in other contemporary countries, notaries had important functions. They drew up contracts and other legal documents that could be enforced by courts, provided legal advice and recognised documents. They developed an important role in credit markets, certifying loan contracts.Footnote 27 In some countries, such as France, notaries even worked as financial intermediaries, providing information to help their clients mitigate the effects of information asymmetries (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2000). Although the number of notarised loans was probably lower than those that were agreed in the informal market, the notary's participation was essential for larger contracts and transactions with foreigners and non-relatives (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2019).Footnote 28

My selection of the city of Malaga as an example is mainly explained by the important role that credit played in its economy. At the end of the 18th century, the city and its surrounding area were among the main Spanish producers of several agricultural commodities, such as wine, raisins, almonds, figs, lemons and oranges. Most of this production was later exported to the markets of northern Europe and former Spanish domains (Fisher Reference Fisher1981; Nadal Reference Nadal2003, p. 34; García Fernández Reference García Fernández2006). Commercial dynamism favoured an increase in population and the accumulation of capital in the city, helping to make Malaga one of the first industrialised areas of Spain during the 19th century (Morilla Reference Morilla1978).Footnote 29 This agro-export pattern was sustained by the city's trading houses and merchants who bought the commodities produced by the farmers and financed them periodically, receiving agricultural commodities in return. As a consequence of this situation, the city's notaries drew up a huge number of agricultural credit contracts (Peña-Mir Reference Peña-Mir2016). The primacy of small properties in this area may also have determined the relevance of credit transactions (Bernal Reference Bernal1981, p. 283; Gámez Amián Reference Gámez Amián and Morilla1995, p. 152). On the one hand, the small size of the plots made it difficult for the owners to accumulate capital or to exploit economies of scale, so they needed periodic loans in order to survive. On the other hand, as many farmers had land that could be offered as collateral, creditors had a greater incentive to lend them money.

I use notarial records for the years 1764 and 1784, that is, before and after the creation of public mortgage registries in 1768. These were years of peace and economic recovery after the Spanish participation in the Seven Years' War (1762-1763) and the American Revolutionary War (1779-1783). I have recorded two similar samples of obligation contracts (obligaciones) signed in Malaga in 1764 (1,307 contracts) and 1784 (1,181 contracts).Footnote 30

Obligations were contracts that «recorded a generic agreement in which a person recognized the mandatory nature of paying a debt or carrying out a future work» (Carvajal Reference Carvajal, Coffman, Lorandini and Lorenzini2018, pp. 216-217). They were used mainly as short-term loans: 82.5 per cent of obligation contracts drawn up in Malaga in 1784 had a duration of 1 year or less, the average lifetime being 10.3 months. Here, they were used mostly to finance agricultural activities, but they also served other purposes such as the recognition of debts, credit sales and payment of urgent expenses.Footnote 31

Two main reasons explain the selection of obligations—short-term credit—instead of annuities (censos consignativos and censos reservativos)—long-term credit—and other credit modalities.Footnote 32 First and foremost, in Castile, annuities were always supported by special mortgages, whereas obligations were not always supported by specific assets. As I want to measure the impact of special mortgages on credit conditions before and after the 1768 reform, I need to compare general mortgage and special mortgage contracts of the same kind. Second, the number of obligation contracts is much higher. For example, obligations constituted 22.8 per cent of the notarial deeds written in Malaga in 1784, whereas annuities accounted for only 1.4 per cent (Table 4). This is not a particularity of Malaga: from the mid-18th century, obligations replaced annuities as the main credit contract in many areas of Spain including Murcia (Pérez Picazo Reference Pérez Picazo1987), León (Rubio Reference Rubio1989), Alicante (Cuevas Reference Cuevas1999), Madrid (Sola Reference Sola and Torres Sánchez2000) or Almería (Díaz López Reference Díaz López2001), and the same process also occurred in other countries, such as France (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2019, pp. 62-66). Of course even in these areas obligations would only appear more frequent in terms of flow. Because annuities had much longer lifetimes and the loaned amounts were usually larger, they were superior in terms of stock until well into the 19th century (Milhaud Reference Milhaud2018, pp. 20-23).Footnote 33

TABLE 4. NOTARIAL RECORDS DRAWN UP BY NOTARIES OF MALAGA IN 1784

*Note: this category includes marriage and alimony obligations, concession and tax farming contracts, recognitions of tax and ecclesiastical debts and smugglers' pardons.

Source: see footnote No. 30.

Ideally, I would like to verify whether special mortgage contracts were effectively registered. However, the mortgage registry books for the judicial district of Malaga were destroyed during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) (Cabrillana Reference Cabrillana1984, p.84). Nonetheless there is evidence that a public mortgage registry was indeed created. On 2 December 1774, Lorenzo Ramírez, the oldest town hall notary in the city, paid a bail bond to rule the registry in the city. He mortgaged his office, valued at 16,500 r.v. and three houses valued at 30,500 r.v. This is a very large amount, taking into account the fact that the Council of Castile had only requested the mortgage of the office and additional assets valued at 11,000 r.v. (Archivo Histórico Municipal de Málaga, caja 343, expediente 2). There is also evidence that the information in the registry was used by tribunals to solve litigation. For example, in 1784, in a court case between Manuel Gordon and Alonso García, Gregorio Martínez de la Ribera, the oldest town hall notary and the person responsible for the mortgage registry, was summoned to provide evidence about the property García had included as a special mortgage in the contract that the two parties had signed 1 year earlier (AHPM, libro 3136, pp. 214r-217v). Finally, in 1784, all those contracts that incorporated a mortgage on lands, real estate, offices or annuities included a clause that forced the contracting parties to go to the registry and register the mortgage.

4. IMPACT OF PUBLIC MORTGAGE REGISTRIES ON NOTARIAL CREDIT MARKETS

In order to evaluate the effects of public mortgage registries on Malaga's notarial credit market, I compare obligation contracts that secured the capital with all present and future assets of the debtor (general mortgages) and contracts that added specific property as collateral (special mortgages) in 1764 and 1784. Before 1768 neither general nor special mortgage contracts written in the city of Malaga were recorded in a mortgage registry.Footnote 34 As a result of the 1768 law, a public mortgage registry was created in the city, and it became compulsory to register contracts with special mortgages on certain assets (lands, real state, offices and annuities). If the registry enhanced the legal protection of creditors' property rights, I should observe improved conditions for debtors in special mortgage contracts after the creation of the registry but not earlier. In other words, contracts with special mortgages should have similar conditions to contracts with general mortgages in 1764, but they should have significantly better conditions in 1784.

To assess whether public mortgage registries had an impact on contracts, I estimate the following model, using ordinary least squares (OLS):

CAPITALi denotes the size of the contract in r.v. I have removed contracts that did not mention any amount and I have adjusted contracts written in 1784 for the inflation accumulated since 1764.Footnote 35 Why is the size of the contract chosen as the dependent variable instead of using the interest rate? It has certainly been suggested that interest rates in capital markets are the best measure to evaluate the efficiency of the institutional framework (North Reference North1990, p. 69).Footnote 36 However, variations in interest rates were insignificant in credit markets characterised by a high degree of information asymmetries, for example, urban credit markets during the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. As price measurement was costly, lenders would not change interest rates but would discriminate among potential borrowers using other variables instead, such as the quality of the collateral or the reputation of the borrower (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2000, p. 300; Van Zanden et al. Reference Van Zanden, Zuijderduijn and De Moor2012, p. 19). This point is crucial for early modern Spain, where obligation contracts rarely included interest rates.Footnote 37 Most contracts stated that the amount was being provided «at the mercy of the lender». As has been suggested, lenders may have included the interest in the amount supposedly given by the creditor to avoid the usury laws (Tello Reference Tello1994, p. 14; Zegarra Reference Zegarra2017b, p. 81).Footnote 38 For this reason, I estimate the impact of special mortgages by looking at changes in loaned amounts.

Yeari is a dummy variable that takes value 1 if the contract is from 1784, and equals zero otherwise, to account for temporal trends. Mortgagei is a dummy variable that takes value 1 if the contract includes a special mortgage and equals zero otherwise. Contracts rarely mentioned the value of the mortgaged assets—which does not mean that lenders had no knowledge of it—so the effect of special mortgages on capital is measured in accordance with whether or not this guarantee was present. I have removed contracts that included non-registrable collateral according to the 1768 law (cattle, harvest, tools, devices, boats and cargoes). Thus, the regression includes only general mortgage contracts and registrable special mortgage contracts. It should be noted, however, that general mortgage and special mortgage clauses were complementary: contracts could include both clauses, only one or neither of them. However, in early modern Spain, it became increasingly common for all notarised contracts to include general mortgages, so negotiations revolved around the inclusion of an additional special mortgage over a specific property (Serna Vallejo Reference Serna Vallejo1995, p. 167).Footnote 39 The main advantage of special mortgages was that they linked contracts to specific assets. This link was maintained until repayment. Thus, a debtor could sell the properties used as special mortgages, but, in case of default, the creditor had stronger rights over those properties than the new owner. In contrast, if the contract was supported with a general mortgage only, the properties of the debtor could be sold without that lien and the creditor did not have any rights over them (Sigüenza 1767, pp. 40-41; Diario de México 1808, pp. 126-127 and 133-136). All the contracts in my database included a general mortgage, but just over half of them added a special mortgage. The percentage of contracts supported by special mortgages differs widely in these two years: 84.1 per cent in 1764 and 23.9 per cent in 1784. In 1764, the majority of contracts included this clause, while in 1784, its presence appears to be correlated with the amount loaned: the larger the capital, the higher the chance of a contract including a special mortgage (Table 5).

TABLE 5. PERCENTAGE OF CONTRACTS AND AMOUNTS SUPPORTED WITH SPECIAL MORTGAGES IN 1764 AND 1784

*Note: this range only includes two contracts in 1764 and three contracts in 1784.

**Note: this range does not include any contract in 1764 and only two contracts in 1784.

Source: see footnote No. 30.

Yeari × Mortgagei is an interaction variable that appears only when the year is 1784 and a special mortgage is included, in order to measure the incidence of special mortgages in the presence of a public mortgage registry. If my hypothesis is correct, neither the year nor the inclusion of a special mortgage should be significant by themselves. It is only their interaction that should be statistically significant, as it is only after the creation of a public mortgage registry that special mortgages should have an effect on amounts loaned.

Statusi is a dummy variable that takes value 1 if the contract includes the status of the debtor and equals zero otherwise. As noted above, Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2000) and Van Zanden et al. (Reference Van Zanden, Zuijderduijn and De Moor2012) consider reputation to be—along with collateral—the main variable used by lenders to discriminate between potential debtors. The reputation of debtors cannot be established from contracts directly, but its impact can be approached by looking at whether the status of the borrower was mentioned or not. Only 5.26 per cent of the contracts in my database included such a mention.Footnote 40 This could be motivated by the need of some groups, such as the military or the Church, to confirm or renounce their corporate privileges. Alternatively, debtors might have wanted to emphasise their material capacity to repay the loan, in which case mentioning their status could serve as a signalling mechanism. The majority of debtors who mentioned their status were of high or medium social rank and had regular rents from lands, real estate, annuities or tithes (priests, ecclesiastical institutions and aldermen), high public salaries (army and royal officers) or large trading profits (merchants and trading houses). Additionally, many of them belonged to organisations and corporations that could support them in case of default (the army, guilds, professional associations, etc.). Having the means to repay a loan is obviously not the same as having the intention to do so, but there was an indisputable element of prestige in both cases. Therefore, I expect status to have a significant effect on the amount of the contract. Finally, epsilon is the error term.

Table 6 shows the main results. As I expected, the year variable and the special mortgage variable are not significant by themselves. However, the interaction term that combines both variables has a significant impact on the size of capital. This suggests that the mere introduction of a special mortgage did not have noticeable effects over loaned amounts. It was only when the effectiveness of this clause became guaranteed by a well-performing registry that debtors received larger amounts. Thus, special mortgage contracts drawn up after the creation of the public mortgage registries received, on average, around 3,000 r.v. more than general mortgage contracts (drawn up in 1764 or 1784) and special mortgage contracts drawn up before 1768. In 1784, contracts with special mortgages on registrable assets were more than twice the size of contracts with a general mortgage only. In 1764, in contrast, there were no significant differences in the amounts loaned through different type of contract (see Appendix 2).Footnote 41 This is consistent with the hypothesis that the reform of 1768 had a positive impact on the allocation of credit resources.

TABLE 6. OLS REGRESSION RESULTS: IMPACT OF THE MORTGAGE REGIME AND THE STATUS OF THE BORROWER ON THE CAPITAL

t-statistics in parentheses.

Significance levels: *P < 0.1, **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

Source: see footnote No. 30.

Before 1768, the absence of public mortgage registries made it difficult to determine whether the collateral had already been mortgaged or not. Consequently, although creditors demanded the introduction of this clause as a preventive mechanism, it had no impact on loaned amounts. After 1768, new special mortgages began to be registered and trust in their effectiveness increased. This new institution helped clarify the seniority of lenders, improving the functioning of the market. The creation of a public mortgage registry did not increase the number of contracts with special mortgages in the short term, but rather the opposite, as evidenced by the fact that they decreased from 84.1 per cent of all contracts in 1764 to 23.9 per cent in 1784.Footnote 42 However, public mortgage registries ensured a better use of special mortgages. Debtors who wanted large amounts were required to include them, whereas general mortgages were enough for those who borrowed smaller amounts. Probably one of the main consequences of the creation of the public mortgage registry in the short term was a major segmentation of the notarial credit market. A huge number of debtors would become indebted through several small- and medium-value general mortgage contracts. A small percentage would continue using special mortgage contracts, but in smaller numbers and for larger amounts.Footnote 43 These results suggest that, contrary to traditional historiography, public mortgage registries helped to improve the protection of property rights in early modern Spain.

Finally, the status dummy has a large positive effect on the capital of the contract. Contracts that mentioned the status of the borrower were 6,300 r.v. larger than those that did not. Since this variable includes both 1764 and 1784 contracts, it shows that high- and medium-ranked members of the community could rely on their status to obtain larger amounts during the entire period.Footnote 44 This emphasises the importance that these types of mechanisms played in the absence of more sophisticated institutions, such as registries. It also suggests that the creation of the public mortgage registry helped to encourage more impersonal financial transactions. Once the debtors were able to strengthen their position as property owners, they could sustain their credit relationships on the basis of the quality of their collateral, becoming less dependent on their status. This would be especially helpful for low-status debtors. In this regard, registries were surely not enough to create a purely impersonal credit market, but they were probably a step forward in this direction. Notwithstanding the above, the number of observations is low and the statistical effect is not highly significant, so further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This article has examined the degree of protection given to creditors' rights in Spanish notarial credit markets at the end of the early modern period. I have focused on the role played by public mortgage registries in order to explore the extent to which formal institutions fostered a high level of contractual compliance in these markets. The creation of mortgage registries was a long and contested process that began in the 16th century and was characterised by constant breaches of the law and clashes between the monarchy and the municipalities over their control. Ultimately, in 1768, a network of accessible public registries was created in many Spanish areas. This change was favoured by better organisation of the registries, greater awareness of their importance and the fact that the monarchy renounced its control of the institution. Although these registries experienced many problems until they were replaced by public land registries in the second half of the 19th century, their creation in the late 18th century improved the allocation of credit resources.

To test this hypothesis, I have relied on a sample of almost 2,500 obligation contracts drawn up in the city of Malaga, before and after the creation of these registries. My analysis shows that, before the creation of public mortgage registries, contracts that included special mortgages on lands, real estate, offices and annuities received the same amounts as contracts that only included general mortgages—whose guarantees were theoretically weaker. After the creation of the public mortgage registries, however, contracts with special mortgages on those assets received more than twice as much as those that only included a general mortgage. Once special mortgages began to be registered regularly, they started to have real effects on credit conditions. Although initially the creation of a public mortgage registry did not increase the number of contracts with special mortgages, from that moment this clause helped debtors to obtain larger loans.

The results also suggest that public mortgage registries could have helped to create more impersonal markets. Debtors whose status was included in the contract—usually individuals of high and medium social rank who enjoyed regular incomes and/or who belonged to large organisations—received higher amounts than non-status debtors both before and after the creation of the mortgage registry. For these individuals, the creation of the registry was not so important because their social position helped them mitigate the reluctance of creditors to give them larger loans. For other debtors, however, other institutional arrangements were required, and the creation of the registry could have been one of them. Nevertheless, since the sample of observations that mention the status is small and the statistical effect is not highly significant, further research is needed in order to confirm or discard this hypothesis.

As my results refer to a single city, they must be interpreted with caution. This is especially relevant in a context of jurisdictional fragmentation characterised by a high degree of political autonomy on the part of the municipalities. Thus, the introduction and impact of public mortgage registries could have been conditioned by the economic needs of each judicial district, as well as by the degree of support for them among the elites, the notaries and the local judicial system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank the financial support provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education. I also want to thank Blanca Sánchez Alonso, the editor of Revista de Historia Económica—Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History. I am particularly indebted to my supervisors Yadira María González de Lara Mingo and Yolanda Blasco-Martel, without whose suggestions and support I would never have been able to write this paper. I have benefited from many comments by two anonymous referees as well as those of Carles Sudrià Triay, Alfonso Herranz-Loncán, María Alejandra Irigoin, Oscar Gelderblom, Germán Forero-Laverde, Pablo Fernández Cebrián, Nicolás Nogueroles Peiró and Antonio Carmona Portillo. I gratefully acknowledge comments by Anne Murphy, Tim Van Der Valk and the rest of the participants at the residential training course organised by the Economic History Society (Manchester, December 2017). Very special thanks are due to Pau Belda-i-Tortosa and Xabier García Fuente for their help and support. The usual disclaimers apply.

SOURCES AND OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS

Archivo Histórico Municipal de Málaga: caja 343, expediente 2 (1775).

Archivo Histórico Provincial de Málaga: protocolos notariales de Málaga capital (1764), libros 2472, 2492, 2626, 2709, 2773, 2854, 2872, 2895, 2908, 2950, 2953, 2997, 3009, 3032 and 3081. Protocolos notariales de Málaga capital (1784), libros 2859, 2914, 3006, 3027, 3047, 3049, 3050, 3136, 3150, 3160, 3167, 3174, 3195, 3236, 3256, 3269, 3306, 3323, 3331, 3338, 3356, 3365, 3383, 3390 and 3392. Protocolos notariales de Málaga capital (1808), libro 3639.

Catalogues: Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, Archivo del Reino de Galicia, Archivo del Reino de Mallorca, Archivo del Reino de Valencia, Archivo Histórico de Mahón, Archivo Histórico de Protocolos de Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Archivo Histórico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Archivo Municipal de Écija, Archivo Real y General de Navarra, and Archivos Históricos Provinciales (44 Spanish Provincial Historical Archives).

Diario de México (1808), Tomo VII (September-December, 1807). Ciudad de México: Oficina de Don Juan Bautista de Arizpe.

Ley Hipotecaria (1861). Madrid: Ministerio de Gracia y Justicia.

Los Códigos Españoles Concordados y Anotados (1851). Madrid: Imprenta de la Publicidad.

Novísima Recopilación de las Leyes de España (1805). Madrid: Imprenta de Sancha.

LEGAL HANDBOOKS

ALCARAZ Y CASTRO, I. (1762): Breve introducción del método y práctica de los cuatro juicios. Madrid: Oficina de Domingo Fernández de Arrojo.

BUSTOS RODRÍGUEZ, M (2005): Cádiz en el sistema atlántico. La ciudad, sus comerciantes y la actividad mercantil (1650-1800). Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz.

FEBRERO, J. (1783): Librería de escribanos e instrucción jurídica theórico práctica para principiantes part 1, vol 3. 3 edn. Madrid: Imprenta de Don Pedro Marín.

FEBRERO, J. (1786): Librería de escribanos e instrucción jurídica theórico práctica para principiantes part 2, vol 3. Madrid: Imprenta de Don Pedro Marín.

MARTÍNEZ SALAZAR, A. (1789): Práctica de substanciar pleitos executivos, y ordinarios, conforme al estilo de las chancillerías, audiencias y demás tribunales del Reyno. 4 edn. Madrid: Librería de Hurtado.

SIGÜENZA, P. (1767): Tratado de cláusulas instrumentales. Madrid: Imprenta y librería de Don Antonio Mayoral.

APPENDIX 1

LIST OF REGISTRIES CREATED IN SPAIN BEFORE 1768*

APPENDIX 2

VARIATIONS OF AVERAGE CONTRACTS ACCORDING TO TYPE OF MORTGAGE IN 1764 and 1784 (GENERAL MORTGAGE = 100)