Introduction

Since 2014, the Swedish Social Democratic-Green Party Government has pursued a feminist foreign policy (FFP), with the outspoken goal to become the ‘strongest voice for gender equality and full employment of human rights for all women and girls’.Footnote 1 This initiative has been characterised as ‘a normative reorientation of foreign policy’.Footnote 2 Three other statesFootnote 3 have since initiated feminist aspects in their foreign policies: Canada's Feminist International Assistance Policy,Footnote 4 France's Feminist Diplomacy,Footnote 5 and Mexico's feminist foreign policy.Footnote 6

However, already a cursory examination of the policies reveal that the four states have interpreted the underlying feminist norms differently, emphasising various elements in their respective approaches. The goals of this article are to compare the FFPs in these countries, to establish similarities and differences between them, and to explain the reasons for their respective strategic choices.

In doing so, we combine two International Relations (IR) theories – norm translation theoryFootnote 7 and strategic narrative theory.Footnote 8 Norm translation theory has been used to show how individual states interpret norms of international organisations and global conventions into their domestic contexts. In contrast, strategic narrative theory has been applied to demonstrate how states form and project soft power onto other states. Compared to the norm translation theory, which focuses on national appropriation of international norms, strategic narrative theory is about states telling stories to international audiences; stories that might not necessarily be about norms. Combining these theories can show how states translate international norms to their own advantage by producing strategic narratives to advance their soft power ambitions abroad. Bringing a norm perspective into the strategic narrative theory constitutes a novel contribution of this article. The comparative approach helps to demonstrate how a ‘package’ of international norms is related to by different states: by focusing on certain aspects and not others, states can help to further international norms and at the same time use them strategically for their own purposes.

The theoretical question we ask is ‘How do international norms get translated into strategic narratives of states?’, followed by the empirical question of ‘How do FFPs of Sweden, Canada, France, and Mexico compare in translating international norms into their strategic narratives?’ Empirically, the article relies on policy documents; government's communication in form of press releases, official statements, public speeches, embassy statements, and articles in national and international media from the four FFP countries. We analyse this material using qualitative content analysis.

The article is structured as follows. After having first outlined the main components of the four FFPs, we introduce our first theoretical tool, norm translation theory. We then conceptualise FFPs in terms of strategic narratives, formed through norm translation, and present five factors that may influence the way in which countries chose to strategically interpret existing norms. We proceed with describing our methodological approach, followed by the empirical analysis, a structured comparison of the four FFPs linked to an analysis of reasons for their differing approaches. We conclude by summarising our findings and offering suggestions for future research in understanding the relationship between norm translation and strategic narratives.

Feminist foreign policies (FFPs): An overview

While the concept of FFP had existed in academic circles before Sweden launched it, its application on a state level is new.Footnote 9 Its content, however, is not. The norms underlying any FFP have been laid out in international conventions aimed to protect women's rights, enhance female participation in public life, and empower women economically.Footnote 10 For example, the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) presents eradication of gender-based violence as a way to ensure women's sexual, reproductive, political, economic, and social rights. Furthermore, the 2000 UNSC Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) introduces female participation in conflict resolution and peace negotiations as a way to enhance women's representation in decision-making. A FFP then becomes a step further by making the norms of international conventions visible in practice in state relations with other countries.

A FFP has not only been characterised as ethical, but also radical,Footnote 11 as it aims to apply a gender equality lens to foreign policy – ranging from diplomacy and development, to trade and defence– in bilateral relations with other countries.Footnote 12 While being norm-based, a FFP is also a pragmatic policy.Footnote 13 Even though it uses the word ‘feminist’ – a word historically reserved for political movements and activists – it does not only pursue an activist agenda. It also aims to improve women's conditions around the world within the existing growth-oriented and patriarchal system.Footnote 14 For that, existing FFPs have received critique.Footnote 15 Promoting an ethical foreign policy while not fully abiding by its principles at home and abroad presents a challenge. For example, Sweden and Canada have been criticised for selling weapons to repressive regimes who violate women's rights,Footnote 16 while Mexico and France have been denounced for failing to stop the rising numbers of femicide in their countries.Footnote 17 One goal of this article is to understand how the FFP states address this challenge in a comparative perspective.

The introduction of a FFP may be linked to strong ideological, normatively based convictions (‘this is the right thing to do’), but also to the strategic strengthening of the initiator's self-images internationally. As Ann Towns argues, ‘[s]tate behavior towards women has often provided an opportunity not only to differentiate among states but also to evaluate and rank states in a hierarchical manner’.Footnote 18 Some of the FFP countries (Sweden, Canada) have a long-standing reputation as ethical powersFootnote 19 with an ideological heritage as promoters of human rights, and not least gender equality. Being a pioneer by initiating a feminist policy attracts attention and can consolidate a country's image as a vanguard and frontrunner. For France, introducing a FFP helps to bolster its broad great power ambitions by adding a moral component. For Mexico, the FFP both supports its ambitions as a regional leader and adds credibility to its domestic fight against femicide. A FFP may also become a catalyst for recognition at a multilateral arena, as evidenced by the Canadian (2018) and French (2019) presidency in the Group of Seven (G7), and the Swedish (2017–18) and Mexican (2021–2) non-permanent seats on the UNSC after their FFP launch.

The four countries in this study that have officially adopted and are implementing FFP relate to international norms by foregrounding certain gender issues and backgrounding others.Footnote 20 The Swedish FFP has been the first to date (since 2014) and remains the most comprehensive of all four. In 2016, the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs presented long-term FFP objectives for six focus areas, which promote women's rights as human rights, women's participation in politics and peace processes, economic rights, freedom from violence, and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).Footnote 21 Being comprehensive, this policy applies gender lenses to diplomacy, trade, aid, and security spheres of action.

In comparison, the Canadian policy has been more modest. Introduced as ‘Feminist International Assistance Policy’ (FIAP) in 2017, development assistance has been its primary focus. Within this focus, the Canadian FIAP also has six action areas that prioritise gender equality and human rights, economic growth, climate action, inclusive governance, and peace and security.Footnote 22 Being a member of the G7, the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promoted this policy during the 2018 Canadian G7 presidency by creating the Gender Equality Advisory Council to include gender equality and gender-based analysis across all areas of G7 work.Footnote 23

Compared to Canada, French FFP has been more comprehensive. Termed ‘feminist diplomacy’ (FD) and used interchangeably with the concept ‘feminist foreign policy’, French FD prioritises aid and diplomacy as the country's spheres of action. Its five areas of intervention focus on appointing female leaders, gender mainstreaming, gender-budgeting, gender-friendly language, and collaboration with civil society.Footnote 24 France took over the G7 presidency after Canada in 2019 and promoted its FD through this channel.

The next country to adopt a FFP was Mexico. Announced in 2020, Mexico's FFP includes five priority areas, with a feminist approach across all areas of foreign policy, making equality visible, gender parity within the foreign ministry, combatting gender-based violence and an intersectional approach to foreign policy.Footnote 25 Mexico specifically focuses on working with FFP in the Latin American region and regional forums using an intersectional lens. Mexico followed Sweden and won a non-permanent UNSC seat in 2020. We suggest that each country's different take on FFP can be understood as norm translation, which we conceptualise below.

Norm translation

Norm translation theoryFootnote 26 has developed as a response to norm diffusion theory.Footnote 27 While the proponents of norm diffusion prioritised a linear approach of norm spread from global to local, the scholars of norm translation emphasise a more diverse process of norm spread. As Susanne Zwingel argues, ‘I use the term “translation” here instead of “diffusion” because translation implies that differently contextualized norms may be translated into another realm, for example, from global to national or local to national, whereas diffusion assumes a one-way influence from global to non-global.’Footnote 28 This definition fits into how FFP reflects international norms. On the one hand, FFP relies on already existing norms that have been articulated in international conventions (translation from international to national level). On the other hand, FFP appropriates these norms into its domestic context (national level) in order to apply them in diplomatic relations with other countries (international level).

The value of norm translation theory is in its emphasis on incompleteness and selectivity of norm spread. Anke Draude argues that ‘[t]he meaning of a translation only applies in its context; as soon as it crosses boundaries, its content changes fundamentally. There are no ‘true’ translations in the sense of a positivist ontology.'Footnote 29 This implies that there can be no universally acceptable and applicable FFP, as translating FFP from one context to another would simultaneously modify its content. As Zwingel contends, ‘translation of global norms into domestic practice remains principally incomplete’.Footnote 30 In this translation process, certain normative aspects are selected, while others are lost.

Based on these developments in norm translation theory, we argue that in a chain of translating gender equality norms in Sweden, Canada, France, and Mexico, each of these states produces its own version of FFP, understandable and applicable in its national context and on the international stage.Footnote 31 As the next section argues, norm translation is reflected in a country's strategic narrative.

Strategic narrative stages in norm translation

Strategic narratives are stories that states tell about themselves, other states, and a current state of world affairs by formulating a problem and proposing a solution that would create a positive image of their Selves on the international arena, help achieving their objectives, and persuade others to follow suit.Footnote 32

There exist three stages of strategic narrative; that is, formation, projection, and reception.Footnote 33 Formation is a stage of producing a new or modifying an old story about the current state of world affairs, which is achieved by setting an agenda for international actors to follow. In respect to FFP, the formation stage is where the formulation of the importance of feminist foreign policy for the world takes place. Furthermore, the projection stage of a strategic narrative is about the medium of its delivery; it includes main narrators of the desired story and the public spaces where this narration takes place. In FFP, main narrators include state actors and diplomats, while the medium of transmission includes all possible governmental and non-governmental channels. Finally, the reception stage of strategic narrative is the effect this narrative has on its receivers. The reception stage does not imply that strategic narrative recipients are passive actors consuming what is being given to them. On the contrary, they are active agents in accepting, modifying, or rejecting strategic narratives.

We argue that norm translation is realised at all three stages of the strategic narrative. One state can first be influenced by the strategic narrative of another state. The norm influenced state then develops its own version of a strategic narrative through translation of the international norms into its own context. In the case of FFP, Sweden, Canada, France, and Mexico act as both norm takers at home (of the basic norms from international conventions) and as norm promoters abroad (of their FFP as expressed in their strategic narratives). In this article, we only focus on the stages of formation and projection of four FFPs as strategic narratives.

Influencing factors in the formation and projection of strategic narratives

We argue, following norm translation theory, that the formation and projection of strategic narratives are influenced by several factors. The first influencing factor is norm imprecision:Footnote 34 The less precise the norm is, the easier it is to accept it by other states in order to mold it into their local context. As IWDA policy brief shows, ‘there is no single definition of a feminist foreign policy’.Footnote 35 This means that each country has an opportunity to offer their own FFP definition.

The next influencing factor is previous work the country has already done on gender issues. If some progress has already been achieved in improving certain aspects of gender equality at a national level, these aspects tend to be in focus also in its strategic narrative. The third influencing factor for the formation and projection of a strategic narrative is the gender problems yet to be solved either nationally (at home) or/and internationally (abroad) and which of these are prioritised.

The fourth influencing factor is continuous participation and engagement in international collaboration on gender problems. All of the FFP countries have signed and ratified CEDAW, adopted the national plans as a response to the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), and launched action plans for the implementation of WPS. The last influencing factor is an ability to preserve the country's unique identity and the legitimacy of its actions.Footnote 36 All FFP countries articulate their uniqueness through FFP by being the first country in the world to address a certain gender aspect.

Strategic narrative types in norm translation

Laura Roselle, Alister Miskimmon, and Ben O'Loughlin identify different types of strategic narratives: international system narratives, national narratives, and issue narratives.Footnote 37 International system narrative implies that the state creates and projects its favorable vision of the world and its problems. It is a narrative of ‘how the world is structured, who the players are, and how it works'.Footnote 38 In relation to the FFP, an international system narrative articulates broader global problems (for example, poverty, international insecurity, migration, etc.) to be solved by addressing gender inequality.

National narrative means that political actors formulate and disseminate an image of the Self at home and abroad. According to Roselle and colleagues, national narrative is ‘what the story of the state or nation is, what values and goals it has’.Footnote 39 The national narrative incorporates gender into the vision of the nation, be it a gender equal nation, a sexual minorities welcoming nation, a nation free from gender-based violence, and so on. Incorporating gender into the national narrative is a way to upgrade the vision of the Self and to manifest how the nation wants to be seen by others.Footnote 40

Finally, issue narrative focuses on the current problem at stake and desirable solutions that need to be undertaken. It is a story of ‘why a policy is needed and (normatively) desirable, and how it will be successfully implemented or accomplished’.Footnote 41 The issue narrative would zoom in at selected gender problems relevant for the country in question.

We argue that these three strategic narrative types constitute the content of FFP at its formation and projection stages. The next section suggests that these three strategic narrative types are influenced by the existing narratives of feminism.

Feminist narratives as strategic narratives

There are many types of feminist narratives, but those relevant in this article are liberal and intersectional feminist narratives.Footnote 42 A liberal feminist narrative advocates an increased presence of women in existing institutions. It stands not only for integration of women into existing institutions, but also for promotion of women into leadership positions of these institutions. Furthermore, liberal FFP supports legal reform for gender equality, women's human rights, and success of individual women. Liberal feminism does not oppose militarism, unlike pacifist feminism,Footnote 43 which allows pragmatism and idealism to co-exist in a FFP.

The liberal narrative is the most common narrative of international organisations, international conventions, and states. Market feminism,Footnote 44 security feminism,Footnote 45 legal feminism,Footnote 46 and rights-based feminismFootnote 47 all constitute liberal feminist narratives. Market feminism concerns emancipation of women through entrepreneurship brought by international financial organisations and private companies.Footnote 48 Market feminism favours economic growth; economic empowerment of women through a FFP can become a way to achieve growth. Furthermore, security feminism relates to securitisation of female bodies in areas of conflict, as well as in peace times.Footnote 49 According to security feminism, a FFP can address sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and SRHR locally to achieve security globally. Moving on to legal feminism, it relies on the law as a means of access, institutionalisation, and practice of gender equality.Footnote 50 A FFP can make a reference to the law or introduce a new law to advocate for gender parity in public institutions. Finally, rights-based feminism stands for universalisation of women's entitlement for political, economic, and social equality.Footnote 51 In order for women to acquire the same rights as men, a FFP can advocate for women's rights as human rights. These subtypes of liberal feminism have been criticised for not addressing the impact of economic globalisation on gender inequality and for prioritising human rights over economic and social justice.Footnote 52

An intersectional feminist narrative stands for gender equality between women, men, and non-binary persons and social justice among people of different race, ethnicity, class, and other social markers. This narrative is primarily found in NGOs, social movements, and grassroots organisations. For example, when talking about the rights of migrant women of colour, the need for combating racism and religious phobias and ensuring social justice can be articulated.

Methodology

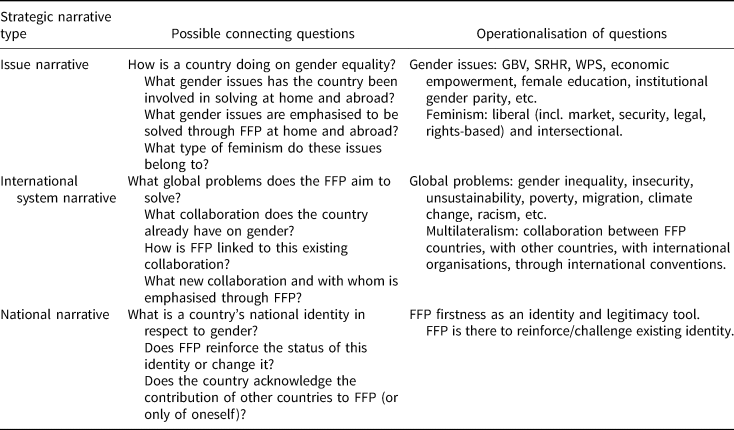

To map each FFP as a strategic narrative in four states, the texts from government communication on FFP were collected from Nexis-Uni and online (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary material) in the form of policy documents, press releases, public speeches, official interviews, embassy statements, op-eds, but also media reports (Table 1). In total, 110 texts from 46 sources were selected for the analysis.Footnote 53 Using qualitative content analysis,Footnote 54 the information on FFP in the selected texts was coded for the three strategic narrative types and two types of feminism (Table 2). The conceptualisation of liberal and intersectional feminism was based on Christine Alwan and S. Laurel Weldon's typology.Footnote 55 The operationalisation of liberal feminism into market, security, legal, and rights-based feminisms stemmed from both the data and FFP focus areas and from the academic literature discussed above, using an abductive logic,Footnote 56 thereby constituting an issue narrative. International system narrative was operationalised by linking liberal feminism to multilateral cooperation on solving global problems of gender inequality, insecurity, unsustainability, poverty, and intersectional feminism. Finally, national narrative was operationalised by linking liberal and intersectional feminisms to the state identity and its geopolitical positioning within the Global North or the Global South.

Table 1. Data collected per type.

Table 2. Operationalisation of strategic narrative types.

It should be noted that each of these FFPs may be contested domestically and challenged by contending narratives, based on competing conceptions of state identity, with different prioritisation of FFP and with alternative interpretations of what constitutes a FFP. For analytical purposes, the narratives are being treated as singular and coherent in our analysis.

Analysis: Comparing four FFPs

Sweden's FFP: Strategic issue narrative

Gender equality has been prioritised by Swedish governments since the 1970s: ‘Sweden made a name for itself early on with its progressive gender equality policy featuring social reforms to strengthen women and girls at every stage of life and in all forums.’Footnote 57 A gender equality approach has influenced its foreign aid prior to the introduction of the FFP,Footnote 58 but with it, Sweden has scaled up its ambitions. The three most prioritised FFP focus areas are presented below (see Appendix 2 in the supplementary material).

SGBV is one of the most prioritised areas, to which Minister for Foreign Affairs Margot WallströmFootnote 59 brought experience and knowledge from her previous position as UN special representative on sexual violence in conflict. The FFP focuses on how Sweden can contribute to decrease SGBV abroad – not least in places of conflict – by helping the victims and bringing proceedings to perpetrators, as well as rehabilitating soldiers. During its stint at the UNSC, Sweden contributed to have ‘sexual and gender based violence as a stand-alone criteria for [UN] sanctions’.Footnote 60

Another highly prioritised area is women's participation in conflict resolution. The UNSC Resolution 1325/WPS has a strong standing in Sweden. Sweden adopted its first National Action Plan in 2006 and has now implemented its third (2016–20). WPS was a priority during Sweden's period in the UN Security Council, where some success was achieved: ‘since Sweden took up a place on the Council, all of the Council's statements have mentioned women, peace and security’.Footnote 61 The argument that women need to be included in peace processes in order to have sustainable peace has been intensively communicated.Footnote 62 Through the FFP, a Swedish network of women peace mediators has been established, and Sweden has been involved in the co-establishment of a Nordic equivalent as well.Footnote 63

A third highly prioritised area is sexual and reproductive health and rights. Sweden was comparatively early in introducing reforms in relation to SRHR domestically. The FFP is focused on issues such as sexuality education, maternal health, providing contraception and safe and legal abortions. Sweden was one of the countries increasing its development aid related to SRHR as a reaction to the Trump administration's introduction of the gag rule.Footnote 64 The pushback against women's rights in this area has been brought to attention in government material. In a speech, Wallström applauded progress made in the UN on sexual violence in conflict, while at the same time questioning the lack of SRHR in the same resolution (UN resolution 2467):

The resolution is important and we have welcomed it. … However, sexual and reproductive health and rights were not included in the resolution. … In other words: the international community could not agree on stating the need for basic sexual and reproductive health and rights of survivors of sexual violence in conflict. Shall we deny these victims emergency contraceptives? Safe abortions? The right to know about their bodies, to know about HIV and AIDS? With all our knowledge, with everything we know and are capable of – is this where we want to be?Footnote 65

With regard to the type of feminism found in Sweden's FFP, it clearly builds on liberal feminism. Women's rights as human rights are at its core, but it also draws upon security feminism. Intersectionality is mentioned in the Handbook, recognising that other factors than gender is important to take into account, but in other forms of communication it is overall absent. The focus on economic empowerment of women has a market feminist approach. Overall, the FFP is based on ‘mainstream’ liberal feminism,Footnote 66 and this is also how it is presented in different forms of outreach.

Sweden's FFP: Strategic international system narrative

The main problem that the FFP aims to solve is gender inequality, which manifests itself in many different areas and the policy therefore has to focus on different aspects (rights, representation, resources; see Appendix 3 in the supplementary material). Decreasing gender inequality will have positive effects not only for women:

Our work is based on the premise that gender equality is not just a women's issue – it benefits everyone. Research shows that gender-equal societies enjoy better health, stronger economic growth and greater security …Footnote 67

Gender equality is linked to democracy and ultimately what is good, as stated by Wallström in a speech:

These examples concern gender equality, but this is really part of a larger struggle, between democracy and authoritarianism; between openness and repression; between hope and fear: yes, one might even call it the struggle between good and evil.Footnote 68

International cooperation is important, not least due to the pushback of women's rights and the decline of democracy in many places around the world. Sweden builds its FFP on previous international commitments, and regards multilateral institutions important for its work. It has been part of several new forms of cooperation, often within the UN framework, such as HeForShe (UN Women), but also in global movements such as She Decides. International insecurity is also a major problem the Swedish FFP aims to address. Here it builds on the WPS framework, emphasising the role of women in, for example, preventing and resolving conflicts. The WPS agenda heavily influenced Sweden's work in the UNSC (2017–18).

Sweden's FFP: Strategic national narrative

The Swedish government has continuously emphasised that it is the first feminist government in the world (see Appendix 4 in the supplementary material), as is its feminist foreign policy.Footnote 69 It is stated that the FFP is both a practical and smart policy, as described by Wallström in an op-ed: ‘Feminism is a component of a modern view on global politics, not an idealistic departure from it. It is about smart policy which includes whole populations, uses all potential and leaves no one behind.’Footnote 70

The government is underlining Sweden's early progress in gender equality, which makes it a legitimate leader in the area: ‘Sweden shall be a role model for gender equality, both nationally and internationally.’Footnote 71 The fact that other states now follow in its footsteps is frequently mentioned. Wallström states: ‘it is encouraging that our feminist foreign policy has received so much attention and gained a following. Canada also pursues a feminist approach to its foreign policy and France engages in feminist diplomacy.’Footnote 72

Canada's FIAP: Strategic issue narrative

The main problem to be solved abroad is poverty, and the best way to do so is through gender equality. In that sense, gender equality is rather ‘the answer’ to a problem.Footnote 73 However, considering the global approach to this issue, it will be dealt with in the next section. Among gender related problems, SRHR, SGBV, economic empowerment, and issues related to peace and security are the ones most prioritised by Canada (see Appendix 5 in the supplementary material).

Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is the first and core area of the FIAP and includes the fight against SGBV. Foreign Minister Chrystia FreelandFootnote 74 has also described SRHR as being at the core of Canada's foreign policy (not only the FIAP): ‘Women's rights are human rights. That includes sexual reproductive rights and the right to safe and accessible abortions. These rights are at the core of our foreign policy.’Footnote 75

Marie-Claude Bibeau, Minister of International Development and La Francophonie,Footnote 76 has been highly active with regard to different initiatives on SRHR. In early 2017, prior to the launch of the FIAP, Canada increased its spending in this area. It also joined, as a core partner, the Ouagadougou Partnership in March 2017, which works with family planning in Western Africa. The work against SGBV has been visible and is present both in relation to SRHR and to peace and security.

Another highly prioritised area is peace and security (at home and abroad). Canada has a strong commitment to WPS. It adopted its first National Action Plan in 2010, and the second in 2017. This commitment is reflected in the FIAP, as is Canada's commitment to the 2030 Agenda, emphasising the link between peace and sustainable development. In line with the WPS agenda, Canada aims to increase the role for women in peace negotiations, conflict prevention, and postconflict state-building. In addition, it will train police and peacekeepers in gender equality. In this area, one of few explicit links in the FIAP to Canada's domestic context is found:

Though much has been done to promote gender equality in the Canadian Armed Forces, more work is needed to ensure that Canada's military reflects and respects the needs of the women it employs and serves. Canada is committed to making its military a true example of gender equality in action.Footnote 77

Hence, Canada is aiming to lead through example when it comes to gender equality and military forces. SGBV is also emphasised in relation to peace and security. Canada states its aim to prevent and respond to these issues in conflict zones – and humanitarian crises – as well as enforcing a zero-tolerance for abuse by peacekeepers.

Yet another highly prioritised area is the economic empowerment of women in the Global South. The action area ‘Growth that Works for Everyone’ aims to give ‘women more opportunities to succeed and greater control over household resources and decision making, as well as reducing their heavy burden of unpaid work, including child care’.Footnote 78 In an op-ed with Kristalina Georgieva, CEO of the World Bank, Bibeau writes: ‘In nearly every country, women and girls face systemic barriers that bar them from full and equal participation in the workforce and the formal economy more broadly.’Footnote 79 Contributing to removing these barriers, the FIAP, for example, promotes women's economic rights, support technical and vocational training for women, and the inclusion of women in economic decision-making.Footnote 80

With ‘women's rights as human rights’ at its core, the FIAP is characterised by liberal feminism, including rights-based as well as security feminism. However, the strong emphasis on economic empowerment of women, and women as agents of growth also means a strong element of market feminism in the policy.

Canada's FIAP: Strategic international system narrative

The main global problem to be addressed is poverty and gender equality will contribute to its eradication (see Appendix 6 in the supplementary material). In the cover letter to the FIAP, Bibeau states: ‘The primary objective of this policy is to contribute to global efforts to eradicate poverty around the world. To achieve this, we must address inequality.’Footnote 81 In the same document, it is also stated: ‘A feminist approach is much more than focusing on women and girls; rather, it is the most effective way to address the root causes of poverty.’Footnote 82 The empowerment of women and girls is thus a means to combat poverty.

Increased gender equality will not only contribute to economic growth, but also to sustainability in line with the 2030 Agenda, another Canadian priority. This message is repeated in different types of communications. Bibeau has written op-eds with World Bank CEO Georgieva, underlining these aspects: ‘The World Bank and the Government of Canada agree that one of the most effective ways to accelerate economic development, reduce poverty and build sustainable societies around the world is to empower women and girls.’Footnote 83

Canadian ministers strongly emphasise their country's commitment to multilateralism and the liberal world order. This is done through collaboration with other states or groups of states, for example, the G7. Other actors, in addition to states, are also important partners to Canada in the fight against poverty and for the empowerment of women and girls, such as IGOs and NGOs, but also private companies.Footnote 84

Canada's FIAP: Strategic national narrative

In the words of Laura Parisi, ‘[t]he FIAP continues the rhetoric of Canada being a “good state”.’Footnote 85 It projects Canadian values and beliefs:

Canada's Feminist International Assistance Policy is a reflection of who we are as Canadians. It expresses our belief that it is possible to build a more peaceful, more inclusive and more prosperous world. It guides our support for the world's poorest and most vulnerable people.Footnote 86

The strategic national narrative also focuses on the contrast between the former Conservative government's lack of emphasis on gender equality in development and the ‘progressive’ and feminist Trudeau government's ambitions in this area, as described by Bibeau: ‘from 1995–2015, Canada's government failed to champion women's rights … It was high time to take a good, hard look at the situation and adopt a new plan, a more ambitious plan, a more feminist plan.’Footnote 87

In addition, Canada portrays itself as a leader in the empowerment of women and girls: ‘It [the FIAP] will make Canada a global leader in promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.’Footnote 88 The approach is framed as something extraordinary – even revolutionary, as described in an op-ed by Bibeau and Katja Iversen, from the NGO Women Deliver: ‘This year's G7 is doing something that some would call revolutionary, and many believe is long overdue: looking at every priority issue through a gender lens.’Footnote 89

The G7 presidency, referred to above, was used to further strengthen Canada's emphasis on gender equality and demonstrating its lead. Through its emphasis on gender equality, the explicitly declared feminist government under Trudeau is ‘leading by example’ in its feminist approach to international assistance.

France's FD: Strategic issue narrative

President Emmanuel Macron has made gender equality his policy priority and initiated FFD with four main pillars: ending gender-based violence, ensuring equitable and quality education and health, promoting economic empowerment, and ensuring full equality between women and men in public policyFootnote 90 (see Appendix 8 in the supplementary material).

In relation to gender-based violence, President Macron suggested giving legal status to the fight against femicide at the United Nations General Assembly,Footnote 91 while the former Minister of State for Gender Equality and the Fight against Discrimination Marlène SchiappaFootnote 92 ‘insisted that her government is waging “feminist diplomacy” abroad and battling at home via new laws against street harassment and cyberbullying’.Footnote 93 In addition, FFD mobilises development assistance to address war rapes and forced marriages in the Global South.Footnote 94 One of the influencing factors to bring SGBV into FFD is high numbers of femicides in France.Footnote 95 Another factor is online bullying, which led to the initiation of the hate speech law in France. Furthermore, the #MeToo campaign led to passing a law against street harassment of women.Footnote 96 France's below average position (28 per cent) in OECD gender-focused aid (38 per cent average) encouraged the French Development Agency to include a gender component in 50 per cent of its projects.Footnote 97

FFD also addresses female education and health via development assistance:

Furthering this feminist foreign policy means working to ensure that both girls and boys around the world get better access to education. To this end and at France's instigation, a conference on girls’ education in Africa will be held in Paris on 5 July, tied in with the Sahel Alliance.Footnote 98

The rationale to prioritise the Sahel region of Africa in FFD is due to it having the highest rates of child marriage and early pregnancies in the world. Countries of this region are all former French colonies, where up to 50 per cent of the population is under 15 years old.Footnote 99 French engagement with the Sahel Alliance and She Decides campaign paved the way to include female education and health into FFD.

When inclusion of women into existing institutions at home is concerned, Minister of Europe and Foreign Affairs Jean-Yves Le Drian states that FFD stands for quota systems and improvement of occupational equality at the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs: ‘We must strive to promote equality at every stage of the recruitment and promotion process, notably by ensuring that candidates of both sexes are well represented on selection panels, in order to ensure greater gender parity among recruits as soon as they join the Quai d'Orsay and throughout their careers.’Footnote 100 FFD also focuses on increasing the number of female leaders in French embassies: ‘In December 2017, there were 50 female ambassadors [that is, 25 per cent of all ambassadors]; there were 9 female directors and heads of service [that is, 28 per cent].'Footnote 101 The quota system introduced in French companies and legislatures has also affected the diplomatic corpus: ‘The Sauvadet Act also requires the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, like all other administrations, to have 40% females among the first appointments to the posts of ambassador or director.’Footnote 102

Regarding economic empowerment of women, Le Drian and Schiappa argue that FFD is ‘a foreign policy to foster women's economic empowerment worldwide, and particularly in Africa’.Footnote 103 More specifically, Macron announced financial support to female entrepreneurship in Africa.Footnote 104 FFD also aims to support female entrepreneurship in France: ‘I'll be deeply involved in writing the boldest and most ambitious French law on women's economic emancipation.’Footnote 105 The rationale to focus on economic empowerment in FFD stems from the importance given to economic growth in G7. Female poverty is also one of the influencing factors: ‘In France, 70% of the population living below the official poverty line are women.’Footnote 106

As for the type of feminism embedded in FFD, rights-based and legal feminisms are echoed in the topics of SGBV and institutional inclusion of women, while the focus on economic empowerment epitomises the elements of market feminism. Legal feminism is expressed in supporting the implementation of rights-based and market feminisms through laws. The rational of FFD is that solving SGBV and institutional exclusion of women helps improving women's access to the marketplace:

I think it is difficult to fight for equal pay if women fear physical harm in the street, when they travel, and even when they go home … It is very difficult in these cases for women to have the necessary mindsets to develop their careers.Footnote 107

France's FD: Strategic international system narrative

Gender issues articulated by France in the strategic issue narrative are also tied to global problems of the international system narrative (see Appendix 9 in the supplementary material). This interlink is created by France's obligations to comply with international instruments and give France an opportunity to position itself as a leader solving global problems via FFD. The primary global problems of French focus are gender inequality (in general, beyond FFD), unsustainable development, and international insecurity.

When addressing global problems, FFD advocates for multilateralism through collaboration between countries via international forums and partnerships: ‘No country can achieve gender equality on its own, which is why I believe deeply in a collective commitment to women's rights in the form of multilateralism, which is the rationale of the feminist diplomacy led by France …’.Footnote 108

FFD has been influenced by the Gender Equality Advisory Council set up by the Canadian G7 presidency in 2018,Footnote 109 the Istanbul Convention,Footnote 110 and WPS.Footnote 111 The 2030 Agenda has also been an influencing factor on the content and conduct of FFD: ‘It [FFD] is aligned with the 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and covers all the pillars of sustainable development (economic, social, environmental, partnership and governance/political).’Footnote 112 References to the 2030 Agenda imply that gender inequality contributes to unsustainable development, especially in the Global South.Footnote 113

France's FD: Strategic national narrative

Since 1789, freedom, equality, and brotherhood have constituted French national identity. In his presidential campaign in 2017, Macron suggested to focus on gender equality as one of the national goals (see Appendix 10 in the supplementary material). After winning the elections, Macron created the Secretariat of Equality between Women and Men.Footnote 114

FFD is articulated to distinguish Macron's cabinet from its predecessors and unite France around gender equality: ‘France is back for itself: Gender equality is the great cause of President Macron's term.’Footnote 115 FFD then becomes a means of achieving gender equality at home and abroad: ‘Setting an example in its internal practices is a key part of rolling out the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs’ feminist foreign policy.’Footnote 116 FFD allows projecting an image of France as a global leader:

France is also back for the wider world: Gender equality now needs to become a great global cause. France is back and feminism as well. Let us match the president's commitment in favour of all girls and women, everywhere in the world. Together.Footnote 117

Mexican FFP: Strategic issue narrative

Mexican officials emphasise two main gender issues for FFP to tackle at home and abroad: gender-based violence and female inclusion into existing institutions (see Appendix 11 in the supplementary material). In relation to gender-based violence at home, the Undersecretary for Multilateral Affairs and Human Rights at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Martha Delgado advocates: ‘Feminist foreign policy offers a clear message: government is sensitive to the daily situation of violence against women. Gender-based violence shakes our conscience and we take full responsibility to put all the tools of the state at our disposal to eradicate it.’Footnote 118 One of the influencing factors to prioritise SGBV in MFFP is a high number of femicides. In 2019, 3,825 women were killed in Mexico; 1,006 were victims of femicide.Footnote 119 Another influencing factor is an existing Mexican international commitment to fight femicide.Footnote 120

Moving on to gender-based violence abroad, the Consul General of Mexico in Houston (US) Alicia Kerber Palma states in her op-ed ‘A Year of Feminist Foreign Policy’ that ‘we seek to address the most difficult contexts that migrant women can face, including domestic violence, discrimination, human trafficking and other problems’.Footnote 121 The rationale for focusing on migration in MFFP is that it is no longer seen as solely about men's experience. The influencing factor to address SGBV is a high number of Mexican migrants in the USA.Footnote 122 Another influencing factor is an existing Mexican programme on improving migrant women's conditions: ‘A notable example is the impetus given to the Window for Comprehensive Women's Care (VAIM),Footnote 123 which places women at the center of consular programs and services.’Footnote 124

Concerning the inclusion of women into the existing institutions at home, Delgado states: ‘With the launch of a feminist foreign policy … we strive to achieve gender parity in staffing within the Foreign Ministry.’Footnote 125 One of the influencing factors is that Mexico has achieved progress in including women into the public institutions through the 2014 constitutional reform.Footnote 126 MFFP serves as a way to expand this practice to institutions where gender parity is not achieved. That is because ‘Women, in Delgado's words, have more difficulty accessing jobs that involve living abroad or traveling very often, such as foreign service … We hope that Mexico can have half female and male ambassador.’Footnote 127 Kerber Palma further states that ‘the commitment of a feminist foreign policy is not only limited to the integration of more women into the sector, but also to its incorporation into decision-making positions that allow challenging the political and power hierarchies’.Footnote 128

In terms of the type of feminism that Mexican FFP pursues, fighting SGBV corresponds to the intersectional approach to feminism, while addressing women's exclusion from the government and diplomatic corps is embedded into the liberal feminist thought. ‘An intersectional feminist approach to all foreign policy actions’ is named as one of five MFFP goalsFootnote 129 and includes ‘sexual and reproductive rights; recognising the diversity of women and girls; the differentiated effects of climate change on women; the rights of migrant women; and inclusion of indigenous languages and peoples’.Footnote 130

Mexican FFP: Strategic international system narrative

Mexico links SGBV and inclusion of women to global problems of gender inequality (in general, beyond FFP), international insecurity, unsustainable development, climate change, and racism. These problems are viewed as either causing or being caused by structural discrimination of women. Solutions to these problems are prescribed by international and regional organisations and their conventions, to which Mexico commits (see Appendix 12 in the supplementary material). Mexico's embeddedness into the international and regional structures helps legitimising MFFP and provides a platform for practicing this policy.

MFFP values multilateralism within the existing conventions: ‘Mexico constantly seeks to advance feminist foreign policies in multilateral forums; we do this not only to improve this approach to foreign policy but also to encourage other countries to join this international coalition.’Footnote 131 MFFP has been influenced by BPfA (the main document addressing gender inequality), WPS and 2030 Agenda (which problematise international insecurity and unsustainable development), 2014 UNFCC COP Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG) and 2017 UNFCC COP Gender Action Plan (GAP) (which fight climate change), and 2013 OAS Inter-American Convention against all forms of Discrimination and Intolerance (which tackles racism).Footnote 132

Mexican FFP: Strategic national narrative

For some time, Mexico's reputation has been of a country with a high level of femicides and a masculine culture of drug trafficking and corruption.Footnote 133 Taking an initiative to promote MFFP constitutes a break from the existing identity and a desire to develop a new one (see Appendix 13 in the supplementary material).

Promoting FFP allows Mexico to present itself as the first country in Latin America and the Global South to initiate the policy. Compared to the other FFP countries, Mexico is the only state explicitly acknowledging the contribution of others to FFP: ‘It joins countries such as France, Canada, Norway and Sweden in reaffirming the importance of gender equality for the development of just, peaceful and happy societies.’Footnote 134 Mexico also emphasises its role as a regional actor when pursuing FFP: ‘As the first Latin American country to adopt a feminist foreign policy, Mexico is willing to learn from other countries with more experience, share its benefits, and lead the nations of our region to adopt this foreign policy.’Footnote 135

Discussion: Comparing strategic narratives

Strategic issue narrative

The strategic issue narrative is dominated by liberal feminist ideas and practices in all four cases. At the same time, each state either prioritises particular aspects of liberal feminism (legal, market, security, rights-based) or incorporates aspects from competing feminist thought (intersectional).

Sweden's FFP builds on a liberal feminist narrative, with emphasis on rights-based feminism and security feminism. There is also an element of market feminism, when it comes to economic empowerment of women. Of the three most prioritised areas presented earlier, SGBV and SRHR focus on rights, while the WPS-agenda in FFP has a strong focus on security feminism. The ‘mainstream’ liberal feminism characterising Sweden's FFP derives from its previous domestic reforms as well as international conventions.

Canada's FIAP is also characterised by liberal feminism, emphasising women's rights as human rights. This is evident with regard to SRHR, SGBV, and in relation to peace and security issues, and influenced its establishment of the G7 Gender Equality Advisory Council. However, at the same time, the FIAP also demonstrates a high degree of market feminism. The emphasis of economic empowerment of women can even be described as the overarching goal of the policy – it is not only a goal in itself, but the way to eradicate poverty on a global level.

In the case of France, liberal feminism is present in the form of market and legal feminism. Market feminism advocates for bringing as many women to the labour market as possible, and hence, treats them as an economic resource. Legal feminism is there to administratively assist the smooth functioning of the market. Even human rights-oriented gender issues such as eradication of SGBV and support for female education and health are worth fighting for as long as they can help women entering the labour market.

The strong emphasis on the market reasoning and economic empowerment of women in FFPs of Canada and France is consistent with their membership in G7, where economic growth remains the main driver of world progress. Gender equality is instrumentalised by these countries as a way to speed up economic growth. To do that, gender equality of opportunities is prioritised over gender equality of outcomes.

Finally, Mexico is the only country that brings the perspective of intersectional feminism into its FFP. By incorporating both elements from liberal and intersectional feminisms in its FFP, Mexico is trying to draw attention to issues of particular concern to the Global South, often overlooked by FFP countries from the Global North. These issues include structural discrimination against women of colour, indigenous women, migrant women, and the LGBT community.

A lesser emphasis on the market logic and more attention given to the social policies to gender equality in Swedish and Mexican FFPs can be explained by their status as ‘small states’ on the international stage, and by their left-leaning governments in office during the formation and projection stages of the strategic narrative. Gender equality is not seen as a goal to remedy other world problems, but as a complex problem worthy of attention in its own right. By viewing gender inequality as a problem of broader structural inequalities, Sweden and Mexico offer a comprehensive perspective to gender inequality.

What does the dominance of liberal feminism in the strategic issue narratives mean for norm translation? On the one hand, the fact that liberal feminism runs across all four cases implies that the status quo of the basic norm of gender equality as recognised by the international community remains unchanged. On the other hand, the possibility to emphasise different aspects of the basic norm (legal, market, security, and rights-based feminisms) and even incorporating elements of a competing norm (intersectional feminism) means that states have room to adjust the basic norm by localising it into their national context and transforming its content to fit their needs.

Moreover, a divide between economic (Canada and France) and social (Sweden and Mexico) priorities in gender equality demonstrate that there is a split between countries who would like their FFP to be more market or social policy oriented. Furthermore, a divide between the countries of the Global North (in favour of more liberal feminism) and the Global South (in favour of more intersectional feminism), as well as between the ‘big states’ (Canada, France) and the ‘small states’ (Sweden, Mexico) reveals that the basic norm is understood and practiced in different ways depending on the geopolitical and economic hierarchies of states. Finally, different takes on whether the FFP should be practiced primarily abroad (Canada, Sweden) or both abroad and at home (France, Mexico) reveal another nuance in the approach to the basic norm. Both France and Mexico emphasise the importance of FFP application at home and abroad. France calls it a ‘dual approach’ where ‘ownership of gender issues both in terms of professional equality internally at the MEAE, and through gender mainstreaming within France's external action’ is crucial.Footnote 136

Strategic international system narrative

The international system narrative is dominated by references to multilateralism and the primacy of international organisations and frameworks in addressing gender issues through UN 2030 Agenda, BPfA, WPS, and so on. These instruments place gender issues in relation to other global problems such as unsustainable development, international insecurity, poverty, climate change, and others.

For Sweden, the main problem to be addressed is gender inequality, which is manifest in many different forms and builds on structural discrimination of women and girls. To fight for gender equality is not only in the interest of women and girls – everyone will benefit from a more gender equal world. Sweden advocates international cooperation in this effort, which is needed not least due to the pushback of women's rights in many places around the world today. Sweden has a strong commitment to international conventions and treaties on women's rights. It also used its seat in the UN Security Council (2017–18) to promote gender equality and its FFP agenda. The Swedish FFP also views international insecurity as a major problem, and draws heavily on the WPS framework to address it.

Canada's FIAP pictures poverty as the main problem, and gender equality as a way to fight it. By empowering women and girls, growth will increase and this will lead to more prosperous and sustainable societies. At the same time as women and girls in the developing world are described as vulnerable, they are seen as the main agents of change. To Canada, increasing gender equality is hence a means to fight poverty, rather than a goal in itself. Canada is also strongly committed to different international conventions on women's rights, and used its G7 presidency in 2018 to further promote gender equality.

In the case of France, a strong emphasis on UN 2030 Agenda in FFD makes gender equality a tool to achieve sustainable development. In addition to women being an economic resource in need of mobilisation, they also become a resource in achieving sustainable development. By emphasising sustainable development, FFD becomes a way to comply with and implement SDGs on the national and international levels. This is especially noticeable in France's International Strategy on Gender Equality (2018–22), in which ‘the key focuses of France's feminist foreign policy are set out’.Footnote 137 What is interesting is that neither the concept of FFP nor FFD are mentioned even once in this document.

When Mexico is concerned, gender equality is not treated as a tool to solve other global problems, but as a difficult goal to achieve due to other problems creating gender inequality such as racial discrimination, migration, and climate change. Treating gender inequality as a symptom of other global problems, Mexico does not emphasise one particular international instrument to address them, but rather refers to several frameworks.

What does reliance on multilateralism and primacy of international organisations and frameworks in addressing gender issues in the international system narrative mean for norm translation? On the one hand, consistency with international instruments keeps the gender equality norm in FFP more or less the same across countries and constrains each state's ability to substantially change it. On the other hand, choosing which convention to prioritise, which global problem to emphasise, and what relationship to articulate between gender issues and global challenges (does gender inequality exacerbates global problems or do global challenges lead to gender inequality?) provides enough room for manoeuvre for each state in norm localisation and subsequent transformation. For Sweden and Mexico, gender inequality is the main problem and addressing it is the goal of their FFPs. For Canada and France, however, gender equality is the solution to global problems such as poverty and unsustainable development.

Strategic national narrative

The national narrative is dominated by the references to the uniqueness of the Self in addressing FFP. Apart from Mexico, none of the countries tends to refer to each other as inspirations when talking about FFP. Mexico acknowledges the contributions of its predecessors in implementing FFP, but adds that MFFP is bringing a unique perspective from the Global South. Furthermore, Sweden is keen on mentioning Canada and France as its followers by emphasising the Swedish contribution to FIAP and FFD. France only mentions Canada as a predecessor of the G7 presidency, but not as a country with a FFP. Canada does not mention Sweden as its FFP predecessor. This Self-centredness of FFP countries in their strategic national narratives makes it difficult for them to unite and form a coalition of FFP like-minded states with a collective (rather than national) identity.

What does Self-centredness in addressing gender issues in strategic national narrative mean for norm translation? It indicates that a state is keen on engaging with a basic norm, if this norm can help it to look good both nationally and internationally. This is especially the case with ‘small states’ who need to do more to gain international attention. In the case of Sweden and Mexico, both are trying to refer to other countries to ‘back up’ their policy initiatives. In comparison, Canada and France as ‘big states’ have more leverage in the international arena and do not seek substantial support from other states.

Conclusion

This article has argued that states translate international norms into their domestic contexts by constructing strategic narratives that they further utilise to advance their soft power abroad. Looking at the case of feminist foreign policy, the article has compared Sweden, Canada, France, and Mexico in their attempts to interpret gender equality norms as prescribed in international conventions for national and international audiences.

Our findings demonstrate that FFPs are not a unified phenomenon. The four states conceptualise and articulate their FFPs in different ways related to strategic considerations. Each country emphasises the elements of feminism that fit its agenda and its domestic and international image. To a certain extent, FFP states may thus compete by bringing attention to their specific interpretation of FFP and to their specific role or niche in promoting feminist policies.Footnote 138

The revealed differences between these states in approaching their respective feminist foreign policies allow us to conclude that when international norms get translated into strategic narratives of states, they become part of stories that states tell about themselves and others in solving urgent problems. In these circumstances, the content of strategic narratives is no longer solely about the norms, but about actors themselves and their place in the world. This leads us to suggest that norm translation is not just about appropriation and localisation of international norms or about internationalisation of local norms, but also about national identities, images of Self and Others, and perceptions of roles that different states embrace or reject in solving pressing global issues. We therefore would like to open up a theoretical and empirical discussion about the role of strategic narratives in norm translation around the world.

Looking at norm translation from the perspective of strategic narratives also contributes to the scholarship on the instrumentalisation of gender in foreign policy.Footnote 139 This scholarship addresses both potential benefits and harms of such instrumentalisation. While instrumentalising gender in foreign policy might contribute to the establishment of state feminism in other parts of the world, the very idea of this policy being ‘foreign’ reproduces differences in race, ethnicity, religion, culture, and class between those who promote a FFP and those who receive it. By being formulated as a coherent story, feminist foreign policy silences internal contradictions, whether between ‘progressive’ elites and business community, between state representatives and civil society, or between well-off and marginalised women at home and abroad. This article thus invites further studies on instrumentalisation of gender through strategic narratives and norms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the reviewers for their constuctive and engaging comments and the RIS Editorial team for making the process so smooth.

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210521000413

Financial support

This work was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond [grant number P19-0712:1]; Riksbankens Jubileumsfond [grant number P19-0712:1].