A diet high in fruits and vegetables (F&V) is essential for good health and to prevent chronic disease. However, a high proportion of children from Western countries do not meet recommendations for F&V intake( Reference Currie, Nic Gabhainn and Godeau 1 – Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortvliet 4 ). F&V consumption is a key behaviour to target during childhood because dietary behaviours track from childhood into adolescence and adulthood( Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 5 – Reference Wyse, Campbell and Nathan 7 ) and food habits in children are still flexible to change( Reference Birch 8 ). Interventions targeting F&V intake have had limited impact( Reference Epstein, Gordy and Raynor 9 – Reference Wolfenden, Wyse and Britton 11 ). One possible explanation is that some key influencing factors are not addressed in these interventions( Reference Baranowski, Lin and Wetter 12 ).

Using the social ecological theory, children’s home environment is a key setting in supporting or inhibiting healthy eating, as it represents the immediate environment in which the child lives, grows and plays( Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 5 ). Parents determine the home environment. Systematic reviews summarising the literature have concluded that components of the home environment, such as availability and accessibility of F&V, parental role modelling and parental intake of F&V, are related to children’s F&V consumption( Reference Blanchette and Brug 13 – Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ). Factors influencing children’s dietary behaviours vary according to age. In early childhood it is acknowledged that children are most dependent on their parents and dietary intake is largely influenced by their home environment( Reference Wyse, Campbell and Nathan 7 ). However, it is unclear how the home environment influences F&V consumption in children aged 6–12 years, especially as they enter primary school, gain more independence and competing influences like the media, peers and the school environment come into play. An increasing number of studies have been published on this topic in recent years( Reference Blanchette and Brug 13 – Reference Ball, Timperio and Crawford 17 ); however, many of these have included a wide age range (4–18 years old), have not differentiated between children and adolescents and have examined only F&V in combination. Combined analyses of F&V may mask the fact that eating fruits may have different correlates compared with eating vegetables.

Therefore, the current review aimed to explore the components of the home environment that have been studied in relation to children’s F&V consumption, and to examine and add to the existing literature updated to 2015 regarding this relationship, focusing specifically on primary-school children aged 6–12 years.

Methods

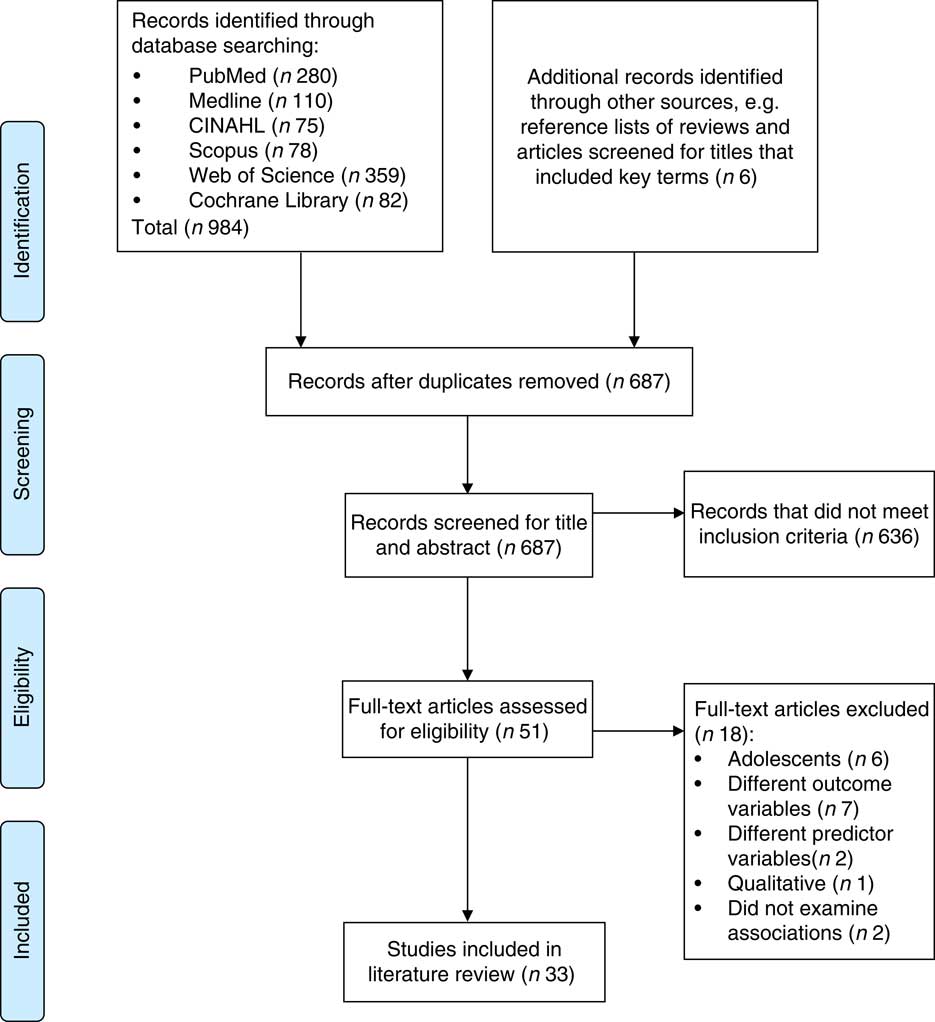

The present review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) systematic procedures( Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff 18 ). The aim was to locate studies which focused on the association between the broad home environment and F&V intake in children aged 6–12 years. The searches were conducted in the following databases: Medline, PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. The search terms were broad and included truncations and synonyms for ‘diet’, ‘fruit’, ‘vegetable’, ‘food habits’ and ‘eating behavior’, which were combined with the Boolean operator ‘OR’ and ‘home environment’, OR ‘parent’, ‘family’. These two search strategies were then combined with the Boolean operator ‘AND’. Both keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used. The searches were limited to English language, child (6–12 years) and publication date of January 2007 to December 2015 where these functions were available in the databases. January 2007 was selected to capture studies after the systematic reviews in this area. The full search strategy is available from the authors on request. Only observational studies were included as the aim was to examine associations and in a non-controlled setting. As depicted in Fig. 1, studies were screened and selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Due to the wide range of possible home environment components obtained from the studies in the review, conceptually similar components were combined under a general category (Table 2). Search and selection of studies were completed independently by two authors using the stated criteria and uncertainties regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies were discussed with other authors until a consensus was reached.

Fig. 1 (colour online) PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram showing selection of studies for the present review

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 2 Summary of studies identified in the present review

NA, not available; OW, overweight; OB, obese; SFVNP, School F&V Nutrition Programme; RCT, randomised controlled trial; NIK, Neighbourhood Impact on Kids; SEIFA, Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas; GROW, Generating Rural Options for Weight; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; PARADE, Partners of All Ages Reading About Diet and Exercise; SES, socio-economic status; Ax, assessment; RSA, Ready Set Action; INPACT, ICO Nutrition and Physical Activity Child Cohort; SEP, socio-economic position; LEAS, Longitudinal Eating and Activity Study; NR, not reported; F&V, fruit and vegetable; PA, physical activity; REAL KIDS, Raising Healthy Eating and Active Living in Kids; CFQ, Child Feeding Questionnaire; CADET, Child and Diet Evaluation Tool; AWPCS, Active Where Parent–Child Survey; PCQ, Pro Children Questionnaire; FEAHQ, Family Eating and Activity Habits Questionnaire; YAFFQ, Youth and Adolescent FFQ; ICC, intra-class correlation; FFE, Family Food Environment; TEENS, Teens Eating for Energy and Nutrition; HBQ, Health Behaviour Questionnaire; DQES, Dietary Questionnaire for Epidemiological Studies; TV, television; GNKQ, General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire; GPPQ, General Parenting Practices Questionnaire; FIS, Food Involvement Scale; EDNP, energy-dense nutrient-poor; NKQ, Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire; FPQ, Feeding Practices Questionnaire; PCA, principal component analysis; HES, Home Environment Survey; KCFQ, Kids’ Child Feeding Questionnaire; CNQ, Child Nutrition Questionnaire; freq, frequency; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; freq, frequency; incl., including; FJ, fruit juice; VJ, vegetable juice; excl., excluding; veg, vegetables; CATCH, Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health; ACAES, Australian Child and Adolescent Eating Survey; BKFS, Block Kids Food Screener; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-age Children; NNS, National Nutrition Survey; DLW, doubly labelled water; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data extracted from studies were: study design, participant characteristics, sample size, recruitment method, measures of predictor and outcome variables, and psychometric properties of measures. Reliability and validity of the tools used for predictor and outcome measures of ≥0·70 was considered acceptable. These are shown in Table 2. All identified components of the home environment were extracted and, using the Analysis Grid for Elements Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework( Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 5 ), classified into three categories, namely home physical, political and sociocultural environment. The home economic environment (e.g. socio-economic status) and demographic factors were excluded as the review was interested only in modifiable components of the home environment.

Table 3 Summary of associations between home environment components and consumption of fruits and vegetables in children aged 6–12 years

(+), positive; (–), negative; (0), nil; PA, physical activity; F, fruit; V, vegetable; F&V, fruit and vegetable; B, boys only; G, girls only; B&T, boys and total sample; G&T, girls and total sample; B&G&T, boys and girls and total sample; I, baseline results from longitudinal studies, II, follow-up results from longitudinal studies.

If boys and girls/fruits and vegetables are analysed separately, they are summarised as individual relationships.

Superscripted numbers in parentheses refer to citation numbers. References for longitudinal studies are in italics.

* Total number of relationships for each home environment component.

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS) developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project( Reference Thomas, Ciliska and Dobbins 19 ), which is suitable and has been validated for use in observational or experimental studies, was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies across five domains (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals and dropouts)( Reference Mackenbach, Rutter and Compernolle 20 ). All identified studies were assessed by a two reviewers and given an overall rating of weak, moderate or strong. The QATQS served to provide insight to limitations within studies and was taken into consideration in combination with findings from the studies.

Summarising associations

Significant (P<0·05) and non-significant associations between the home environment and children’s F&V consumption are summarised in Table 3. Findings from analyses which separated boys and girls, and fruits and vegetables, and baseline and follow-up results from longitudinal studies were summarised separately as individual relationships( Reference Cooper 21 ), as they are likely to have different correlates( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 ). Only multivariate results were included, as significant associations from univariate analyses were generally more abundant and would likely inflate overall findings.

The total number of relationships analysed for each home environment component was determined and the percentage of significant relationships used to determine consistency, which was defined as: no association (0–33 %), indeterminate/inconsistent (34–59 %) and positive/negative association (60–100 %; see Table 3). These methods were based on those that have been used previously( Reference Ferreira, van der Horst and Wendel-Vos 22 , Reference Sallis, Prochaska and Taylor 23 ).

Results

General characteristics of studies reviewed

Within the thirty-three studies in the present review, 205 independent relationships were identified (Table 3). Studies are categorised according to their general characteristics in Table 2. All but two studies were cross-sectional, with follow-up periods between 9 and 36 months in the two longitudinal studies( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 ). Most studies were conducted in the USA( Reference Attorp, Scott and Yew 26 – Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 ) and European countries( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Brown, Ogden and Vogele 35 – Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Te Velde and Maes 44 ). Sample size ranged from fifty( Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 ) to 13 305( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ), and six studies had fewer than 100 subjects( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 – Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore 48 ). Measures of the home environment and F&V consumption varied. Twenty-four studies used scales from existing tools to measure home environment components, while the rest developed new questionnaires( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 , Reference Ding, Sallis and Norman 28 , Reference Perez-Lizaur, Kaufer-Horwitz and Plazas 32 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 , Reference Li, Adab and Cheng 49 , Reference Pearson, Timperio and Salmon 50 , Reference de Jong, Visscher and HiraSing 56 ). From the thirty-three studies, fifteen measured F&V in combination, nineteen measured fruit consumption and seventeen measured vegetable consumption, and definitions differed (Table 2). Five studies reported results for boys and girls separately( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 , Reference Mushi-Brunt, Haire-Joshu and Elliott 31 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Pearson, Timperio and Salmon 50 ). Five studies used only child-reported data, seventeen used only parent reports and eleven used a combination (Table 2). Twenty-three studies adjusted for potential confounders, while in the other ten studies( Reference Attorp, Scott and Yew 26 , Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend 29 – Reference Perez-Lizaur, Kaufer-Horwitz and Plazas 32 , Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg 41 , Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 51 , Reference de Jong, Visscher and HiraSing 56 ), confounding was not reported. Covariates were varied and most commonly included child’s age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status and BMI. Twenty-three studies used regression( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 , Reference Couch, Glanz and Zhou 27 , Reference Mushi-Brunt, Haire-Joshu and Elliott 31 – Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg 41 , Reference Wind, te Velde and Brug 43 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Te Velde and Maes 44 , Reference Marshall, Golley and Hendrie 46 , Reference Li, Adab and Cheng 49 – Reference Zarnowiecki, Parletta and Dollman 52 , Reference de Jong, Visscher and HiraSing 56 , Reference Kunin-Batson, Seburg and Crain 77 ) and eleven used correlation analysis( Reference Ding, Sallis and Norman 28 – Reference Mushi-Brunt, Haire-Joshu and Elliott 31 , Reference Rodenburg, Oenema and Kremers 40 , Reference Van Strien, van Niekerk and Ouwens 42 , Reference Wind, te Velde and Brug 43 , Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 , Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore 48 , Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz 78 ). Only one study used structural equation modelling( Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 51 ).

Measures of effect size varied between studies and were not reported in two studies( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Marshall, Golley and Hendrie 46 ). Only two studies( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Zarnowiecki, Parletta and Dollman 52 ) reported conducting a power calculation, and all but one study provided confidence intervals for results( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ). The home sociocultural environment was most commonly investigated, while the home political environment was less studied. Studies differed in the definition, number and combination of home environment components studied.

Quality assessment

Overall, methodological quality was poor, with twenty out of thirty-three studies rated as weak. This was mainly due to the cross-sectional design in a majority of studies and selection bias as evidenced by the homogeneous sample with limited representativeness (Table 2), recruitment through convenience sampling( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 ) and voluntary participation( Reference Attorp, Scott and Yew 26 , Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend 29 , Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Marshall, Golley and Hendrie 46 , Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 , Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 51 ). About half of the studies had strong–moderate ratings for using valid and/or reliable tools, while, for the other half, psychometric properties were either not reported or weak. Most studies either did not report, or had a low, response or follow-up rate (Table 2). It was not possible to assess publication bias as hypotheses were not reported in many studies.

Similar to a previous review( Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ), only home environment components with three or more significant relationships with combined F&V (described as F&V in the following sections), fruit or vegetable consumption will be reported and discussed, as findings for components that were investigated sparsely, all listed in Table 3, are limited and inconclusive.

Home physical environment and children’s fruit and/or vegetable consumption

Six home physical environment components were identified (Table 3). Availability and accessibility of F&V were most commonly studied and were positively associated with children’s F&V consumption more consistently than other components. All five studies examining home accessibility( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Perez-Lizaur, Kaufer-Horwitz and Plazas 32 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 , Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz 78 ) reported a positive association, although the strength of the relationship was unclear due to lack of reporting in two studies( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 ). With respect to home availability, no association with F&V consumption was found when it was measured through direct observation using a shelf inventory( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 ), compared with parent reports of perceived home availability in the three positive relationships found( Reference Ding, Sallis and Norman 28 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 ), with Robinson-O’Brien et al. also including child reports, although the effect size was not reported in their study( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 ). One study reported home availability as the strongest correlate (r=0·342, P=0·001)( Reference Ding, Sallis and Norman 28 ). These studies were conducted predominantly in Americans from low-income backgrounds( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Perez-Lizaur, Kaufer-Horwitz and Plazas 32 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 ), except for one in London( Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 ), thus limiting the representativeness of findings.

The consistently positive association was evident only for home availability in relation to frequency of vegetable consumption (OR=1·27; 98 % CI 1·12, 1·44)( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ) and at follow-up (OR=2·14; 95 % CI 1·17, 3·91, P<0·05)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ), and was found to be most strongly related to frequency of vegetable consumption (β=0·652, P<0·001)( Reference Amuta, Jacobs and Idoko 53 ) and meeting guidelines for vegetable consumption (OR=2·62; 95 % CI 1·61, 4·26, P<0·001)( Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg 41 ). Despite the more consistent association found for vegetable consumption (six of eight relationships) than fruit consumption (five of nine relationships), associations tended to be stronger for fruit consumption in van Ansem et al.’s study (OR=4·08; 98 % CI 1·75, 9·48)( Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg 41 ) and at baseline (OR=2·97; 95 % CI 1·65, 5·46, P<0·05)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ) than for vegetable consumption. Collectively, all studies had the strength of adjusting for common confounders except for the only study where no significant association with F&V consumption was found, in which confounding was not reported( Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 ).

Home sociocultural environment and children’s fruit and/or vegetable consumption

Twenty-four home sociocultural environment components were identified (Table 3), but most were investigated sparsely. Parental modelling was positively associated with children’s F&V consumption in four of seven relationships( Reference Couch, Glanz and Zhou 27 , Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend 29 , Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 ). No association was found longitudinally( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 ). All studies measured parent-reported parental role modelling, and Draxten et al. also included child reports( Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend 29 ). It should be noted that there were methodological limitations in these studies, as detailed in Table 2.

Parental modelling was also related to higher intakes of fruits (four of six relationships)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 , Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz 78 ) and vegetables (five of seven relationships)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 , Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz 78 ), although the positive associations obtained only slightly outnumbered those with none. All three studies which analysed fruits and vegetables separately were predominantly in the Netherlands( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 ). Operationalisation of parental modelling was inconsistent; in six studies reporting a significant positive association( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 , Reference Wolnicka, Taraszewska and Jaczewska-Schuetz 78 ), parental intake was used to define modelling, while in another study with no association( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 ) it was defined as avoiding negative modelling. In the only study where it was the strongest correlate of children’s F&V consumption (OR=0·68; 95 % CI 0·34, 1·02, P<0·001), parental modelling was measured on the same scale as parental encouragement and thus the association may have been blurred( Reference Couch, Glanz and Zhou 27 ).

Parental intake was defined as a component distinct from parental modelling, as the former solely refers to the amount or frequency of fruits and/or vegetables consumed by the parent. Parental role modelling may refer to the parents being a role model through their intake, but may also encompass other aspects like their feeding attitude, eating styles and mealtime behaviours( Reference Brown and Ogden 54 , Reference Scaglioni, Salvioni and Galimberti 55 ). In the present review, parental intake was positively associated with children’s F&V consumption, especially in mothers( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 ), although no studies examined this relationship in fathers. When F&V consumption was analysed separately, maternal intake appeared to be a stronger correlate than fathers’ intake, whereas weak positive associations were found when mothers and fathers were not differentiated( Reference Raynor, Van Walleghen and Osterholt 33 , Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and Candel 39 ). Paternal intake was positively associated with fruit but not vegetable consumption( Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 ). However, these studies consisted of a homogeneous sample of predominantly overweight Australian fathers( Reference Hall, Collins and Morgan 45 , Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 ), and parents reporting dietary intake in the identified studies were mostly mothers.

Indeterminate associations with children’s F&V consumption were observed for parental encouragement, with half of the six relationships from five studies( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 , Reference Couch, Glanz and Zhou 27 , Reference Gross, Pollock and Braun 30 , Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan 34 , Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 ) showing no association( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 , Reference Christian, Evans and Hancock 36 ) including those at follow-up( Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij 25 ). This was similar for fruit consumption (three of four relationships)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ). Associations were more consistently positive for vegetable consumption (five of six relationships)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ), although no association was found at follow-up as well( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ).

Similarly, inconsistent findings for parental facilitation/support as a correlate of children’s F&V consumption were found, mainly due to the varied components in this category, each of which was investigated infrequently (see Table 2). Nevertheless, strong, positive associations in relation to children’s fruit consumption were reported for cutting up fruit (OR=1·34; 98 % CI 1·20, 1·51) and bringing fruit to school (OR=2·75, 98 % CI 2·43, 3·12), regardless of gender( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ), but no association was found longitudinally( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ). Similarly, cutting up vegetables (OR=1·16; 98 % CI 1·03, 1·31) and bringing vegetables to school (OR=1·99; 98 % CI 1·68, 2·36) were strongly and positively associated only with girls’ and combined boys’ and girls’ vegetable consumption( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ). Longitudinally, the positive association was weakened from baseline (OR=2·57; 95 % CI 1·32, 4·98, P<0·05) to follow-up (OR=2·12; 95 % CI 1·12, 4·01, P<0·05)( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ). Weaker associations were found for cooking together most days of the week (OR=0·64; 95 % CI 0·41, 0·99, P<0·05) and doing groceries together 2–4 d/week (OR=0·94; 95 % CI 0·81, 1·09, P<0·05)( Reference de Jong, Visscher and HiraSing 56 ). However, despite the same specific combination of home environment components measured, the same Pro Children Questionnaire used and large sample size, these findings for parental encouragement and facilitation/support are limited in generalisability as they were mostly obtained from studies by De Bourdeauhuiji et al.( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ) and Tak et al.( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ), where study populations were part of the same projects in Europe.

Home political environment and children’s fruit and/or vegetable consumption

Findings for most of the home political environment components examined in relation to children’s F&V consumption were sparse and thus inconclusive (Table 3). However, having demand rules was positively related to fruit consumption in three of six relationships( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ), including those at baseline( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ). Associations were of similar strength in analyses for gender groups, although not significant for girls( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ). Compared with fruit consumption, demand rules had stronger and more consistent associations (83 % of relationships) with children’s vegetable consumption, persisting from baseline (OR=3·10; 95 % CI 1·66, 5·79, P<0·05) to follow-up (OR=3·06; 95 % CI 1·64, 5·68, P<0·05), and this association was the strongest and most consistent compared with other components investigated( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ). However, these results were also obtained from the two European studies by De Bourdeauhuiji et al.( Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ) and Tak et al.( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ), and thus should be interpreted in view of the limitations mentioned previously.

No association was found between F&V and allowance rules( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ), but there were positive associations with vegetable consumption in girls, combined boys and girls, and at follow-up in three of five relationships( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ).

Composite measure of the home environment

Only two studies, both conducted in Adelaide, Australia, examining the association between the overall home environment and children’s F&V consumption were identified in the current review( Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 51 , Reference Zarnowiecki, Parletta and Dollman 52 ). Findings were inconclusive despite all associations with fruits and/or vegetables being significantly positive in both studies, likely due to differences in the combination of components measured.

It is evident that studies in the present review were highly heterogeneous in methodological design and quality, limiting the ability to compare results. In line with previous reviews( Reference Blanchette and Brug 13 , Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 , Reference van der Horst, Oenema and Ferreira 15 , Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 , Reference Ferreira, van der Horst and Wendel-Vos 22 , Reference Sallis, Prochaska and Taylor 23 ), results presented have focused mainly on the consistency of associations and not the magnitude of associations across studies, as the heterogeneity in effect estimates and lack of reporting in some studies also limited the direct comparison of effect sizes.

Discussion

The present review aimed to add to the existing literature and expand the understanding on the influence of the home environment on F&V consumption in children aged 6–12 years. This could inform the development of more effective interventions to encourage F&V consumption. A vast array of home environment components studied were differentially associated with children’s fruit and/or vegetable consumption, suggesting that specific components of the home environment may have more influence than others. However, studies should be interpreted in light of the heterogeneity in study methodology, design and effect estimates.

The results of the present review showed that the most consistent evidence for children’s combined F&V consumption was found for availability and accessibility of F&V, parental role modelling of F&V and maternal intake of F&V. These components, together with parental facilitation/support and demand rules, showed consistently positive associations when fruits and vegetables were analysed separately; although in some studies, availability, maternal intake and parental facilitation were more strongly and positively associated with fruit consumption, while demand and allowance rules were stronger correlates of vegetable consumption. These findings support previous work that correlates of fruits and vegetables differ( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 , Reference van der Horst, Oenema and Ferreira 15 ), and support the social ecological theory( Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza 5 ) indicating that primary-school children aged 6–12 years are still dependent on their parents and that the home environment is a major influential setting to target.

The present review supports previous findings of the positive influence of home availability and accessibility of F&V on children’s F&V consumption( Reference Blanchette and Brug 13 – Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ). This elucidates the importance of both components, as children may not consume F&V that are hard to access even if they are available, especially if unhealthy foods are also available( Reference Zarnowiecki, Dollman and Parletta 57 ). Most studies in the review reporting positive associations with F&V consumption included parent reports. Currently, there is no gold standard for measuring home food availability; little is known about the accuracy of perceived reports compared with direct observations( Reference Pinard, Yaroch and Hart 58 ). Moreover, agreement between parents’ and children’s perceptions of home availability and accessibility of F&V is low( Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and de Vries 59 – Reference van Assema, Glanz and Martens 61 ). Parents may be more prone to social desirability bias( Reference Pinard, Yaroch and Hart 58 ) and report greater availability of F&V than their children( Reference van Assema, Glanz and Martens 61 ), and child-reported availability was more likely to correlate with F&V consumption and improve internal consistency of scales( Reference Bere and Klepp 62 , Reference Cullen, Baranowski and Owens 63 ). This could explain the inconsistencies in results between studies. If parents perceive availability and accessibility to be good, such a perception could prevent increasing children’s F&V intake. Thus, both parents and children provide invaluable information and different perspectives should be taken into consideration( Reference Robinson, Rollo and Watson 47 , Reference van Assema, Glanz and Martens 61 , Reference Collins, Watson and Burrows 64 ).

Apart from being nutritional gatekeepers controlling home availability and accessibility of F&V( Reference Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski 65 ), parents also act as powerful socialisation agents, influencing children’s food intake by being role models and through the rules they impose( Reference Brug, te Velde and De Bourdeaudhuij 66 ). Past evidence for parental rules was indeterminate and seldom differentiated between demand and allowance rules( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 , Reference Brug, te Velde and De Bourdeaudhuij 66 ). The present review provides new insight to the current literature, showing that demand and allowance rules are positively and more strongly related to vegetable than to fruit consumption. The persistent and stronger associations for maternal compared with paternal intake also attest to the fact that mothers have more influence than fathers on children’s intake and may be better role models. This finding is especially important as maternal employment continues to increase globally, changing the influence of family routines and opportunities for role modelling at mealtimes( Reference Anderson 67 , Reference Cawley and Liu 68 ). With most children not meeting recommendations for F&V( Reference Currie, Nic Gabhainn and Godeau 1 – Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortvliet 4 ), these findings are promising because strategies like encouragement, cutting F&V up, bringing them to school and enforcing demand rules may promote consumption, especially for vegetables. Interventions should not just encourage children’s consumption but also aim to improve parents’ consumption. The indeterminate or absent associations found for all parenting practices (such as parental role modelling), consistent with previous reviews( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 – Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ), indicates that such practices are unlikely to be useful in children age 6–12 years who have increasing autonomy compared with early childhood( Reference Ventura and Birch 69 ). Parents employing these strategies should be informed that these alone will not be adequate for increasing children’s F&V consumption.

Nevertheless, it may be inaccurate to view each component of the home environment independently as they may interact to influence F&V consumption differently. To the authors’ knowledge, the current review is the first time that the relationship between the overall home environment and children’s F&V consumption is summarised, although only two studies were identified( Reference Hendrie, Coveney and Cox 51 , Reference Zarnowiecki, Parletta and Dollman 52 ). However, using an overall measure of the home environment assumes equal contribution of all components and does not enable the identification of the strongest correlate of F&V consumption.

Overall, the evidence presented in the current review is encouraging, but limitations should also be considered before stronger conclusions can be made. Causation and direction of associations cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional design of most studies. It is possible that the reverse is operative as well, such that children’s F&V consumption prompts parental encouragement, practices like cutting up F&V or rules demanding consumption, as supported by Ventura and Birch’s model postulating a bidirectional relationship( Reference Ventura and Birch 69 ). Evidence supporting this is limited. One longitudinal study showed that changes in F&V intake frequency did not predict changes in home environmental components and concluded that the home environment is likely to have a larger impact on F&V consumption( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 ). More research is needed to further explore this relationship.

Cross-sectional data are also limited by confounding. Recent studies have suggested that unhealthy and healthy lifestyle behaviours tend to cluster( Reference Leech, McNaughton and Timperio 70 ) and associations have been shown to be moderated by personal factors, such that children with more positive self-efficacy, liking or preference for F&V may be more influenced by the home environment( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Kremers, de Bruijn and Visscher 71 ). Therefore, these are potential confounders to consider in disentangling the effects of lifestyle factors on F&V consumption.

Psychometric strength of measures used differed across studies. In six of twelve studies using valid measures( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference Ding, Sallis and Norman 28 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference Rodenburg, Oenema and Kremers 40 , Reference Wind, te Velde and Brug 43 , Reference Pearson, Timperio and Salmon 50 ), correlation statistics were used to test for validity rather than the more robust test of agreement( Reference Burrows, Golley and Khambalia 72 ). Parent reports are often used to measure F&V consumption based on the assumption that children cannot estimate portion sizes well( Reference Tak, te Velde and de Vries 73 ), but children above 8 years of age are able to accurately self-report intake( Reference Collins, Watson and Burrows 64 ). It remains unclear whose report is more accurate and valid( Reference Reinaerts, de Nooijer and de Vries 59 , Reference Collins, Watson and Burrows 64 ). More studies investigating their validity are required. Furthermore, the present review used overall fruits and/or vegetables consumption as the main outcome without distinguishing between meeting guidelines, frequency or amount of consumption (Table 2). These were often dichotomised from continuous measures( Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend 29 – Reference Perez-Lizaur, Kaufer-Horwitz and Plazas 32 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 , Reference van Ansem, Schrijvers and Rodenburg 41 , Reference Pearson, Timperio and Salmon 50 ), increasing the likelihood of loss of power and precision of effect sizes( Reference Dawson and Weiss 74 ). While meeting guidelines may be related to enhanced intake, they may have different correlates; children can eat more frequently in limited amounts and may not be meeting recommendations. Also, some included potatoes, or fruit and/or vegetable juice, and most studies used a 24 h recall (Table 2), which may not be representative of usual intake( Reference Collins, Watson and Burrows 64 ). Collectively, these may lead to inconsistencies in measured intake, especially in countries where potatoes and/or juice make up a large proportion of children’s F&V intake( 2 , Reference Faith, Dennison and Edmunds 75 , Reference Slining, Mathias and Popkin 76 ), and may explain the inconsistent associations obtained.

Lastly, a considerable number of significant findings, especially those from separate analyses for fruits and vegetables and gender groups, were from the two European studies( Reference Tak, te Velde and Brug 24 , Reference De Bourdeaudhuij, Velde and Brug 37 ). While effect has been shown to be modified in different groups, they may be limited in generalisability. The multiple strategies employed in the two longitudinal studies also makes it hard to attribute which home environment component brought about change in consumption. Thus, conclusions with regard to home environment predictors of change in children’s F&V consumption are likely to be weak.

Strengths and limitations

The current review is strengthened by its systematic approach and compliance with reporting guidelines. Despite consisting mainly of cross-sectional studies, the findings are useful for hypothesis generation. Similar to past reviews( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 14 – Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ), the present review focused on the consistency of association and not the strength of association. However, as most studies had a large sample size, statistical significance may have been more easily achieved than in smaller studies. Conceptually similar components were combined under a general category but results of studies with stronger methodological quality could be masked by those that were weaker. This was accounted for by considering quality assessment ratings of the studies in our review. Nevertheless, weaker ratings may not necessarily reflect a low-quality study but a lack of reported detail in the papers. Finally, search terms used to retrieve studies from existing databases may not have been sensitive enough and more studies could have been obtained with a more specific search strategy.

Implications for practice/future research

Future studies should be based upon conceptual or theoretical models( Reference Ball, Timperio and Crawford 17 , Reference Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski 65 ) to enhance understanding of mechanisms involved and provide consistency in defining the home environment. New components such as availability and accessibility of unhealthy foods, clusters of diet and activity-related parenting practices and the overall home environment were identified in the present review, none of which were previously examined. Together with those investigated sparsely, they should be replicated to generate more compelling evidence. Analyses for fruits and vegetables and gender groups should be separated where possible. Investigation of potential moderators, such as personal or contextual factors, is also needed to ensure sufficient confounder control in future studies. Stronger longitudinal or intervention studies analysing causation are also warranted. These should be accompanied by improvements in methodological design, through the use of reliable and valid tools specific to the study population, and theoretically driven statistical approaches. These will ensure that interventions to increase F&V consumption among children are evidence based and supported by strong methodological design.

Conclusion

In accordance with social ecological theories, the current review demonstrates the various influences of the home environment on children’s fruit and/or vegetable consumption, adding new insight and further support of previous work( Reference Blanchette and Brug 13 – Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp 16 ). Nevertheless, the relationship between the home environment and children’s F&V consumption is complex and still not well understood. Evidence is consistent only for a limited number of home environment components. Too few studies have been conducted on many of the home environment components to draw strong conclusions.

Nevertheless, parents of primary-school-aged children are important role models who determine the home availability and accessibility of F&V, facilitate easy consumption and enforce rules demanding children to eat F&V. Future interventions promoting F&V consumption in children aged 6–12 years should target both parents and these components of the home environment.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.X.O. and A.M. conducted initial searches. J.X.O. tabled results and drafted the manuscript. A.M. and S.U. provided academic supervision and support in all aspects of the study. A.M., S.U. and E.L. reviewed search results and all authors reached consensus on inclusion criteria. E.L. and J.M. contributed to drafting, critical revision and final approval of the version to be published. All authors reviewed the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.