Current healthcare literature generally identifies fruit and vegetable food prescriptions (FRx) as a viable clinical intervention for improving patients’ dietary consumption patterns, improving patient health outcomes and aiding in the prevention or management of nutrition-related chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes and CVD. While there is no universal protocol or standard of practice specific to FRx, for the purposes of the current study, based on existing interventions and the literature, the authors define FRx as a health focused intervention used by clinical healthcare providers to encourage their patients to improve their dietary consumption patterns by increasing patient access to healthier foods and improving their nutritional literacy (Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Peek, Ferguson and Roberson19). An emphasis on food access for food insecure individuals and disease management are also important provisions in FRx interventions. These interventions typically include a clinical provider writing out a traditional prescription but for quantities of fruits and vegetables rather than medications(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Peek, Ferguson and Roberson19). This prescription is then redeemed in a variety of ways – vouchers at a local farmers market, electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card at a local grocer or retailer or through a mobile market(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Peek, Ferguson and Roberson19). Each of these methods is designed to add money to the household food budget, specifically for fresh fruits and vegetables. Eligibility for these interventions ranges from poor food security status to the presence of a chronic health conditions (obesity, diabetes, pre-diabetes)(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Peek, Ferguson and Roberson19).

FRx interventions can have substantial short- and long-term effects on patient health, aiding in the management of chronic conditions, in the prevention of diseases and reducing long-term health costs(Reference Ridberg, Bell and Merritt13–Reference Saxe-Custack, LaChance and Hanna-Attisha14). Patients with diabetes, in particular, have been targeted in FRx programming. FRx interventions, originally created to benefit patients with diabetes, were eventually expanded to benefit all individuals in need. This expansion resulted in improved access to fresh fruits and vegetables for households, often living in poor food environments and systemically addressed health inequalities in low socio-economic status (SES) communities(Reference Goddu, Roberson and Raffel11,Reference Peek, Ferguson and Roberson19) . Others have documented the role FRx interventions play in reducing diabetes patients’ HbA1c levels and subsequently increasing their healthcare savings by up to $24 000 per year(Reference Hess, Passaretti and Coolbaugh12). While many FRx interventions target those with nutrition-related chronic conditions, others have included those with stroke, cancer, coeliac disease, metabolic disease and women who are pregnant(Reference Hess, Passaretti and Coolbaugh12,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak15–Reference Kearney, Bradbury and Ellahi17,Reference Anand20–Reference Swartz24) . Despite this evidence, the expansion of FRx interventions into mainstream primary care practice has been slow and uneven.

As currently implemented in the USA, FRx interventions rarely recruit through a medical provider but often rely on poor health or presence of a medical condition to determine eligibility(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Joshi, Smith and Bolen18). Yet, studies that have evaluated interventions incorporating clinicians indicate that prescriptions supplied by physicians are generally more highly valued by patients because of the symbolic power and patient-perceived authority of the recommendation(Reference Wetherill, McIntosh and Beachy10). This presents a particular dilemma for practitioners – knowing that clinics are powerful resources in the implementation and effectiveness of FRx interventions, but not understanding the lack of clinic level adoption or involvement.

The examination of this literature highlights a number of potential barriers to FRx adoption by clinical teams. The first is that there is no standard of practice around implementation. Specifically, there is a wide range but no universally accepted method of screening patients for eligibility for participation in FRx interventions. Some healthcare providers screen patients for intervention placement by asking about their SES or food security status, others rely on a predetermined geographic location (typically food deserts), still others rely on health markers such as BMI or diabetes status(Reference Goddu, Roberson and Raffel11–Reference Hess, Passaretti and Coolbaugh12,Reference Cavanagh, Jurkowski and Bozlak15,Reference Joshi, Smith and Bolen18,Reference Anand20–Reference Burrington, Hohensee and Tallman21,Reference Swartz24) . Additionally, there is no standard in terms of which clinician delivers or manages the intervention. While some FRx interventions rely on a single physician as the sole administrator of prescriptions, other interventions rely on teams of healthcare providers, including nutritionists and dieticians, community health workers and assistants, registered nurses, pharmacists and pantry managers, to provide FRx(Reference Hess, Passaretti and Coolbaugh12,Reference Anand20) . Other important barriers include the lack of nutrition education or training for most clinical providers, clinic workflow issues and the need for additional staff for support(Reference Goddu, Roberson and Raffel11,Reference Forbes, Forbes and Lehman16,Reference Schlosser, Smith and Joshi22,Reference Joshi, Smith and Bolen18) . There is also a general lack of discussion of the economic viability of FRx interventions(Reference Sadler, Bontrager and Rogers25).

While the literature provides some insight into what FRx interventions in clinical settings do not have – standardisation, training and support – the literature does not provide any evidence on how this might impact a physician or clinic’s decision to participate in or implement FRx interventions. Given the evidence for the clinical value of FRx interventions, the identified barriers to success and the role traditionally played by various healthcare providers in the rollout of these interventions, a better understanding of healthcare providers’ perspectives is a key factor to understanding which FRx intervention components should be addressed systemically to develop a standard of practice for scaled implementation. This scaled implementation and standardisation is a critical first step in the financial sustainability of FRx interventions that, to date, are not reimbursable by third party payors.

The current study examines the general awareness of and attitude towards FRx among clinicians. Specifically, healthcare professionals were asked to articulate their level of comfort with nutrition advocacy, willingness to utilise a FRx and who they thought would most benefit from such an intervention. Additional questions examined the logistics of FRx implementation, specifically how patients would be screened for enrollment and if the currently available screening tools were adequate. FRx is an emerging approach in clinical care to addressing the system level drivers of obesity, diabetes and other chronic, nutrition-related conditions. However, there are few studies that have examined how clinicians and other healthcare providers involved in primary care perceive these interventions and little is known about the level of awareness of the logistics and the interventions’ potential influence on patient outcomes. Further, studies that examine the usefulness of FRx interventions have an urban bias, with relatively few interventions being implemented in rural spaces(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Joshi, Smith and Bolen18). Little is currently known about the potential for these interventions in rural settings, which often lack the clinical staff for intervention implementation, specifically those with formal nutrition science training, or the infrastructure for food procurement, such as farmers’ markets(Reference AbuSabha, Namjoshi and Klein1–Reference Joshi, Smith and Bolen18). This research addresses, in part or in full, each of these gaps by collecting the perspectives of rural clinicians on FRx interventions.

Method

The current study employed an exploratory research design using in-depth semi-structured interviews. A list of healthcare providers from North and Central Mississippi was generated through an online search for primary care facilities, family practice offices and obesity clinics in North Mississippi as well as through contacts in the region who knew clinics familiar with FRx interventions. Because this region is rural there are relatively few healthcare providers so the sample was pulled from a comprehensive list of all providers who served the areas and had available contact information online. These providers serve predominantly low-income communities. The initial sample included fifty physicians, registered dieticians and nurse practitioners, twelve from Oxford, MS, fifteen from Tupelo, MS, two from Batesville, MS, eight from Jackson, MS, nine from Charleston, MS, two from Grenada, MS, one from Cleveland, MS and one from New Orleans, LA. Each healthcare provider was contacted a total of six times, three times over the phone and three times via email. Lack of response after the sixth contact attempt was considered refusal to participate. Only twenty of the healthcare providers contacted responded to our request for an interview. Of the twenty healthcare providers who responded, two stated that they did not have time to participate; two stated that they did not want to be part of the study, but did not provide a reason and one stated that they did not want to be part of the study because they no longer worked in healthcare. The study sample included fifteen healthcare providers, including three physicians, four registered dieticians, three nurses and three nurse practitioners. Six interviewees, four of whom have used FRx, indicated familiarity with the concept. Nine interviewees indicated no previous knowledge of FRx. Healthcare providers in this sample were predominately white (n 14) and female (n 12). Participants in the same ranged from 26 to 38 years old and had a range of 3–27 years in their current profession, with a majority having over 10 years of experience. Notably, while all participants were associated with primary care facilities, they were not all primary care providers.

Interviews were conducted over the phone and were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent. All interviews were de-identified and appropriate measures taken to protect the identity and privacy of the research participants. The research design and interviewing protocol were approved by the University of Mississippi Institutional Review Board as exempt under 45CFR 46·101(b)(#2ii,iii) – protocol number 20x-048.

Analysis

This research used summative content analysis and simultaneous coding to refine and synthesise the interview transcripts(Reference Hsieh and Shannon26). Interview questions targeted four key areas of inquiry: (1) barriers to implementation, (2) potential use, (3) routinising on-boarding and (4) nutrition education and advocacy. Prior to analysis, keywords within each of these areas, or themes, were identified. For example, within the theme ‘barriers to implementation’, researchers identified five a priori codes (keywords), based on the FRx, to help analyze the data: compliance, nutrition knowledge, access to F & V, clinic workflow and staffing. In order to fully capture all barriers to implementation, an additional category of ‘other’ was specified and codes pulled from the transcripts. Coding was conducted by three researchers using the predetermined coding protocol. The overall between-coder agreement was 81 %. Fleiss’s κ was also calculated for each interview and all had a positive inter-rater reliability (range: 0·255–0·927).

Results

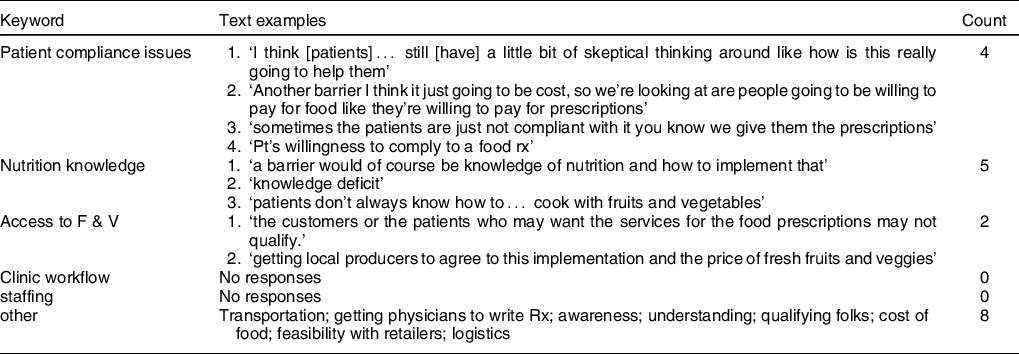

While healthcare providers in this sample did worry about their patients being able to follow-through on their FRx, the most common concerns with the efficacy of this approach were (1) a lack of understanding by healthcare providers of what a FRx is, how it is used and the logistics of administering such a prescription and (2) the cost of food (Table 1). Healthcare providers shared a pervasive concern that even if they could get doctors to write Rx the actual mechanics of such a clinical activity would be a significant barrier and their patients could not afford the food they would prescribe. For example, one participant felt it would be hard to get ‘provider[s] [who] will actually write the script if it’s an actual prescription’.

Table 1 Theme: potential barriers to implementation

While not initially coded as a barrier, healthcare providers were asked about their use of screening tools to enroll patients in a FRx interventions and what they would change about existing tools they may already use. Overwhelmingly, participants, if they used a screening tool (10/15), used some objective health measures (7/10) – lab results, anthropometric assessments (BMI, weight) or the presence of a chronic condition. One healthcare provider mentioned specifically the ‘starting a conversation diet screener’ recommended by the American Medical Association, and the others used SES/income. Those not directly involved with primary care relied heavily on the referral of a primary care provider and did not use screening tools in their practice. Six providers mentioned a need to adjust their screening tool or protocol. These changes indicated a need to have some form of scorable index for need, extra personnel to do the assessment (i.e., ‘diet tech’), the inclusion of other health measures (‘mental health’) or a need to waive current requirements for participation if multiple morbidities are present.

One healthcare provider articulated that it would be helpful to have ‘somebody like a diet tech or a diet aid or a diabetes assistant to do a little bit more in-depth questioning before you send the educator or the clinician in’. Another noted that in their intervention they used an income-based screening process but wished they could ‘make a waiver for those patients, maybe they have one or two comorbidities, and make that be the primary screening process…’

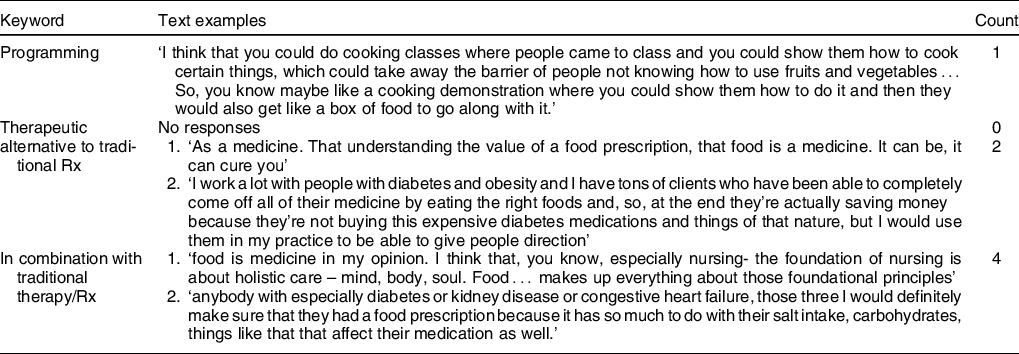

Participants were also asked to envision the target population for a FRx intervention (Table 2). Most (8/15) indicated that patients with diabetes would be the target population, but patients with obesity or other chronic illnesses and patients with low SES were also identified (7/15). A few participants also mentioned targeting patients with pre-diabetes and those who lived in rural areas or food deserts.

Table 2 Theme: potential use (of FRx)

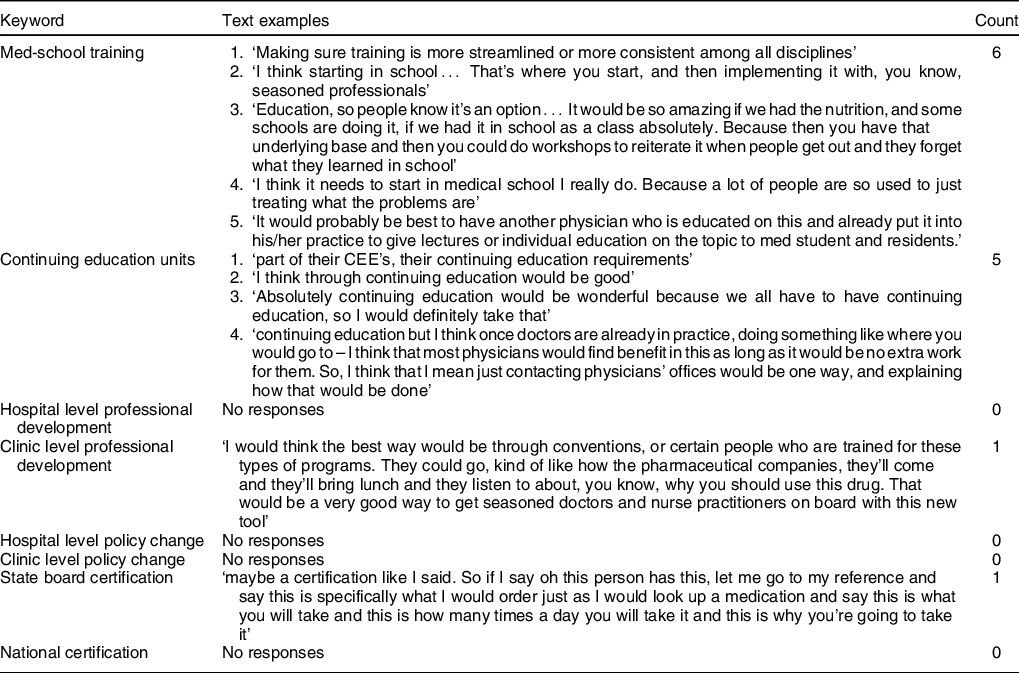

While not all the participants agreed on the ‘how’ of routinising FRx intervention onboarding, all agreed that additional training, education and advocacy were key to successful implementation (Table 3). Several mentioned the need for training across disciplines (nurse, RD, NP, physician), the hiring of specialised staff to assist with on-boarding (population health nurse), weekly or monthly educational seminars and the need for a state or federal agency to take on the responsibility and cost of systemic training. Healthcare providers in the current study also mentioned specific topics where more education was needed, including (1) types and use of screening tools, (2) community education, (3) potential benefits of such an intervention and (4) intervention logistics.

Table 3 Theme: routinising on-boarding

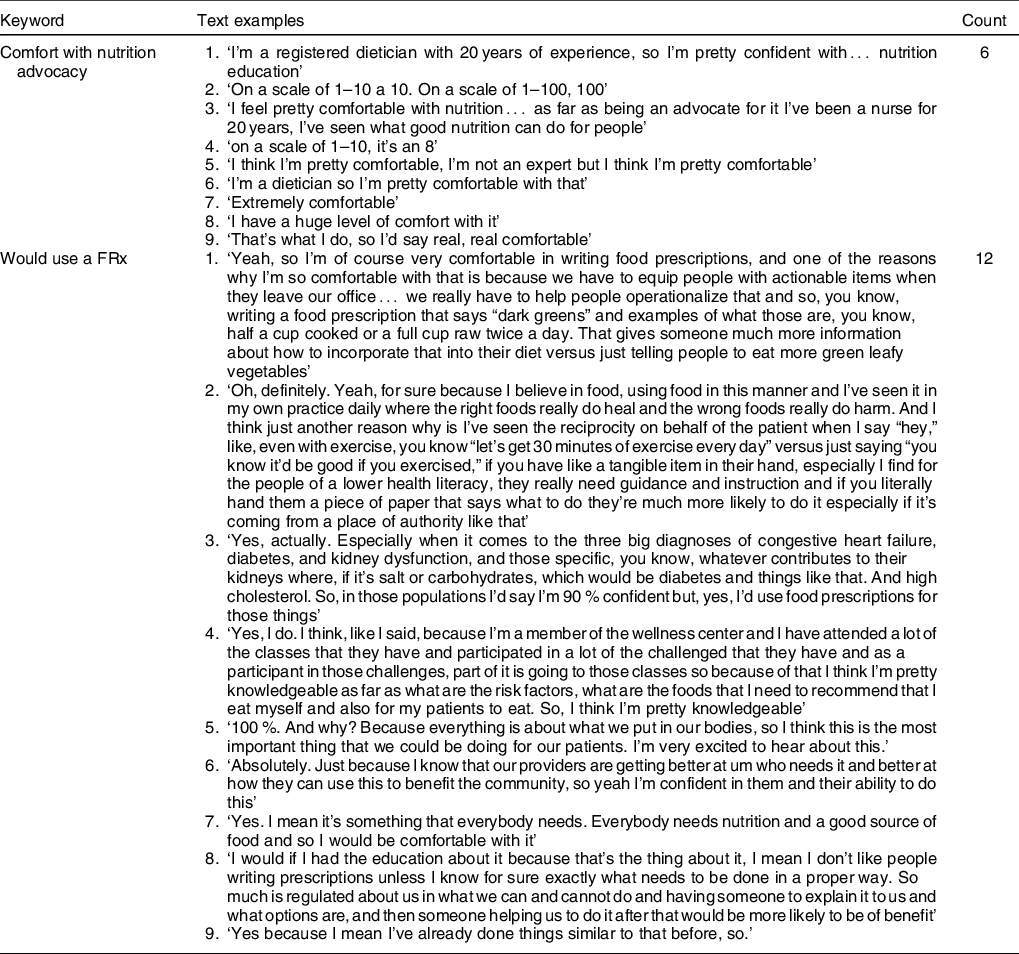

Fewer than half of the healthcare providers felt comfortable with their role in nutrition education and advocacy with patients (Table 4). Notably of the others who were comfortable, most had some training in nutrition (i.e., registered dietitian, had nutrition seminar in medical school). However, all but three participants said they would feel comfortable prescribing more fruits and vegetables.

Table 4 Theme: nutrition and health advocacy

Discussion

The results from the current study highlight three important findings related to healthcare providers’ perceptions and attitudes towards FRx interventions. First, there is a systemic lack of understanding or awareness of FRx interventions. Most interviewees were not personally aware of FRx interventions or reported a concern that many in the field were unaware. While FRx interventions are not a new idea, they are relatively new to clinical settings. A comprehensive review of the literature suggests that these interventions happen in the local food arena – more specifically at farmers’ markets and are usually funded by research bodies or federal agencies (i.e., USDA). While physicians often make the recommendations to their patients to increase fruit and vegetable intake or improve their diet generally, they are not typically involved in the administration of or activities associated with FRx interventions. Additionally, the literature offers up a wide variety of definitions for FRx interventions. Many of the interviewees could not supply a clear definition and were only able to talk about FRx interventions within the context of their practice after researchers provided a definition.

Second is the need for systemic combination screening tools. While a range of screening tools was mentioned by healthcare providers, two things were evident: (1) there was a significant reliance on biometrics as a screening tool, but no consistency across providers about which ones to use and (2) there was very little consideration of non-biometric assessments. Importantly, there was no mention of food security status or the use of the USDA two-item, six-item or long-form assessment of food insecurity as a screening tool. FRx are designed not only to address the nutritional deficiencies in a patient’s diet but also to improve access to food more generally. A number of participants made note of this nuance and indicated a need for being more sensitive to SES and other co-morbidities. This highlights the need for a multifaceted screening tool that allows healthcare providers to screen for the health-related pre-conditions for participation but also food security status and/or income that might make a patient a more compelling candidate for participation in a FRx intervention.

Third is the need for comprehensive, interdisciplinary training programmes for healthcare providers. Patients do not engage with just one type of healthcare professional, rather they engage with an entire healthcare system which can include a multitude of healthcare professionals. Specific training in nutrition is needed across all types of providers. Many of the study respondents identified medical school as a good opportunity to implement nutrition education. The Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine at Tulane University is one such example. Students in this programme learn about food and nutrition in combination with their traditional medical training(Reference McNulty27).

A sample size of 25–30 is ideal for qualitative work, especially grounded research studies(Reference Charmaz28–Reference Morse29). However, in exploratory studies, like this one, where the goal is to develop a base understanding of the phenomenon details (e.g. awareness and attitudes toward FRx interventions) rather than determine how frequent the phenomenon is within the population, < 20 interviews is appropriate(Reference Crouch and McKenzie30). As few as twelve interviews can result in data saturation during qualitative work(Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson31). Despite a small and non-representative (of the whole US) sample was used, the following recommendations are based on the fine-grained details of how healthcare providers interpret, understand and relate to FRx interventions. The following recommendations provide a starting place for improving healthcare providers’ ability to use and implement FRx interventions in clinical settings to improve health outcomes for vulnerable patients.

Recommendations

Based on these findings, the authors have developed three recommendations for improving clinical implementation of FRx for the treatment of chronic conditions:

-

Screening standardisation. Healthcare professionals and healthcare researchers should look to the standardisation and validation of a comprehensive screening tool for enrolling patients into FRx interventions (or similar interventions designed to increase nutrient food consumption). The current study indicates that healthcare providers are seeking tools that combine biometrics with items that help them prioritise patients according to SES and potential benefits to health status. To date, there are a few tools that provide a good foundation for this process. The ‘starting the conversation’ or STC(Reference Paxton, Strycker and Toobert32) assessment performs well for assessing diet quality, as does the CDC’s BRFSS(33). If combined with existing tools for assessing food insecurity, such as the USDA’s two- or six-item screening tool(34), and biometric measures that proxy for long-term morbidities and quality of life, the STC or BRFSS could provide a comprehensive screening tool for providers. Future work should focus on the validation of a combination tool, specifically as it relates to the enrollment of patients in FRx interventions. Until such a tool becomes available, in those places where nutrition education is important, advocating a multifaceted approach to screening is important.

-

Multi-tiered training across disciplines. This training should take place across three arenas: (1) medical or nursing school, (2) continuing education units and (3) a national certifying mechanism. Offering training during initial training and as continuing education units allows healthcare professionals to develop a foundational knowledge and maintain that knowledge over the course of their career. A national certifying mechanism allows professionals who did not receive training in medical or professional school to access that training to better serve their patients. This training should include basic nutrition education, the role of FRx interventions in improving patient outcomes, information and training on screening tools and information on intervention logistics (how to set up, implement and evaluate FRx interventions)(35). To be clear, this approach is not meant to replace certified nutrition therapies as prescribed by registered dietician or advocate for clinicians becoming RD alternatives, but rather to initiate these conversations with patients, direct them to the proper care and provide helpful information.

-

Community advocacy training. Community advocacy is not a part of healthcare training, but clinicians are at the front lines of many healthcare problems. Providing medical professionals with an advocacy framework and the skills to articulate their patients’ concerns to a broad public and policy audience is crucial(Reference Luft36). In part, serious efforts to promote advocacy by healthcare providers start with including this type of education in professional schools and rethinking how students are selected for these training programmes. To move advocacy to the forefront, medical training programmes need to overcome the current emphasis on biomedical knowledge and equally emphasise activities that demonstrate skills related to social justice issues(Reference Mu, Shroff and Dharamsi37). To facilitate the inclusion of advocacy in both initial training and continuing education, it is helpful to consider potential frameworks for health advocacy related to nutrition. University of British Columbia Health Advocacy Framework articulates the role or roles (agency v. activism) providers can have in advocacy and the nature of that advocacy (shared v. directed)(Reference Hubinette, Dobson and Scott38). This model allows healthcare providers to choose from a range of advocacy activities that match the needs of their community, as well as their expertise. Additionally, the Community Health Worker Advocacy Framework, while originally developed for community health workers, readily translates to the work of primary healthcare providers. This framework provides the scaffolding for an iterative, reflective advocacy strategy(Reference Sabo, Ingram and Reinschmidt39). Both of these frameworks could be adapted to apply specifically to nutrition and environmental health.

Conclusion

The current study sought to explore healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards and awareness of FRx interventions. While the healthcare professional interviewed for the current study was generally supportive, findings revealed a widespread lack of knowledge of what FRx are and how they work. However, most healthcare providers agreed that FRx would benefit their patients with chronic metabolic conditions like diabetes and hypertension, as well as those with lower SES. Although exploratory, the current study has several implications for healthcare praxis. First, there is a growing need and desire for interdisciplinary approaches to nutrition within the scope of traditional healthcare practice. The increasing prevalence of chronic metabolic disorders makes multipronged approaches that include traditional medicinal therapies AND interventions that improves access to and knowledge of healthy foods essential. These multipronged approaches require a common understanding of nutrition and health and many healthcare providers lack this training. Additionally, there needs to be consistency across healthcare settings in how patients are enrolled in these types of nutrition/food access interventions. To fully understand the scale and level of impact on health outcomes, consistence in patient profiles is important. This requires validated screening tools that account for current health status and SES.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge our community partner Dr. Catherine Moring who assisted with recruitment. The authors would also like to thank the healthcare providers who agreed to participate in the current study. Each of the authors would also like to thank their respective departments for their continued support. Financial support: This work was not supported through external or internal funding. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest as it relates to the content of this manuscript. Authorship: Each author has contributed significantly to the writing, analysis and editing of this manuscript. K.B.C. was responsible for conducting interviews, completing transcriptions and leading analysis. She also co-led the drafting of the introduction. Drs K.B.C and M.R. were responsible for conceptualisation, research design, quality control of data and analysis. Dr A.C. was responsible for drafting the results and discussion. Dr M.R. was responsible for editing of the final manuscript. D.A. and Q.P. were responsible for data analysis, drafting the introduction and editing of the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the University of Mississippi Institutional Review Board. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded. The research team adhered to all the protocols approved through the University of Mississippi IRB (20X-048).