In a recent article in this journal, Shevlin et al. (Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021) reported that the mental health of adults in the UK, who were surveyed as part of the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) study during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, could be the best described in terms of five profiles. They found that a small proportion of people (~5%) experienced increased symptoms of depression/anxiety and COVID-19-related posttraumatic stress disorder (C19-PTSD), a slightly higher proportion (~6–8%) experienced decreased symptoms of both, and the rest (>~80%) experienced no major changes across the year. These results are consistent with findings from two meta-analytic reviews of changes in population mental health from before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 (Prati & Mancini, Reference Prati and Mancini2021; Robinson, Sutin, Daly, & Jones, Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2021). These studies showed that there was a small increase in symptoms of mental ill health in the first weeks of the pandemic, followed by a return to pre-pandemic levels by May 2020. Here we report results from the now completed C19PRC study in Ireland that assessed the mental health of adults at five points during the first year of the pandemic. Specifically, we present findings on (1) what proportion of adults met the criteria for depression, anxiety, and/or C19-PTSD at each assessment, and (2) if, and how, symptoms and prevalence estimates of these disorders changed during the first year of the pandemic.

The C19PRC-Ireland study is an Internet-based survey of adults living in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethical approval was granted by Maynooth University (SRESC-2020-2402202). Data were gathered across five waves (W1: March/April 2020, W2: April/May 2020, W3: July/August 2020, W4: December 2020, and W5: March/April 2021), and quota sampling was used at Wave 1 (N = 1041) to construct a sample representative of the population with respect to age, sex, and regional distribution. Recontact rates were 49% at W2, 51% at W3, 40% at W4, and 38% at W5. Overall, 26% of those who participated at W1 responded at all waves, and they did not differ from non-responders on all mental health variables. Responders differed from non-responders in being older and less likely to live alone. New participants were selected to fill ‘vacant’ sex, age, and regional quotas at Waves 2, 4, and 5 so that the cross-sectional sample was representative of the population. Wave 3 sample data were weighted using an inverse probability weighting method to produce cross-sectional estimates that were representative of the population. A detailed methodological account of the C19PRC-Ireland study is available elsewhere (Spikol, McBride, Vallieres, Butter, & Hyland, Reference Spikol, McBride, Vallieres, Butter and Hyland2021).

Depression and anxiety were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006), respectively. Symptom scores range from 0 to 27 and 0 to 21 respectively, and scores ⩾10 on both indicate the possible presence of depression and anxiety. The International Trauma Questionnaire (Cloitre et al., Reference Cloitre, Shevlin, Brewin, Bisson, Roberts, Maercker and Hyland2018) was used to measure symptoms of PTSD. Respondents completed the scale thinking about their ‘…experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic’. Scores range from 0 to 24, and the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria were followed to identify ‘cases’ (Cloitre et al., Reference Cloitre, Shevlin, Brewin, Bisson, Roberts, Maercker and Hyland2018). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the cross-sectional prevalence estimates of depression, anxiety, and/or C19-PTSD at each assessment. Longitudinal changes in the means and prevalence estimates of these disorders were assessed using structural equation modeling. Missing data were handled using full information robust maximum likelihood estimation meaning that all analyses were based on the full sample at W1.

The cross-sectional prevalence estimates for depression, anxiety, and C19-PTSD at each assessment can be found at https://osf.io/ekry8/. The proportion of people who met the criteria for any one of these disorders was similar at each assessment: W1 = 34.7% (95% CI 31.8–37.6), W2 = 36.6% (95% CI 33.7–39.6), W3 = 35.4% (95% CI 32.6–28.3), W4 = 34.5 (95% CI 31.7–37.3), W5 = 33.7% (95% CI 30.9–36.5).

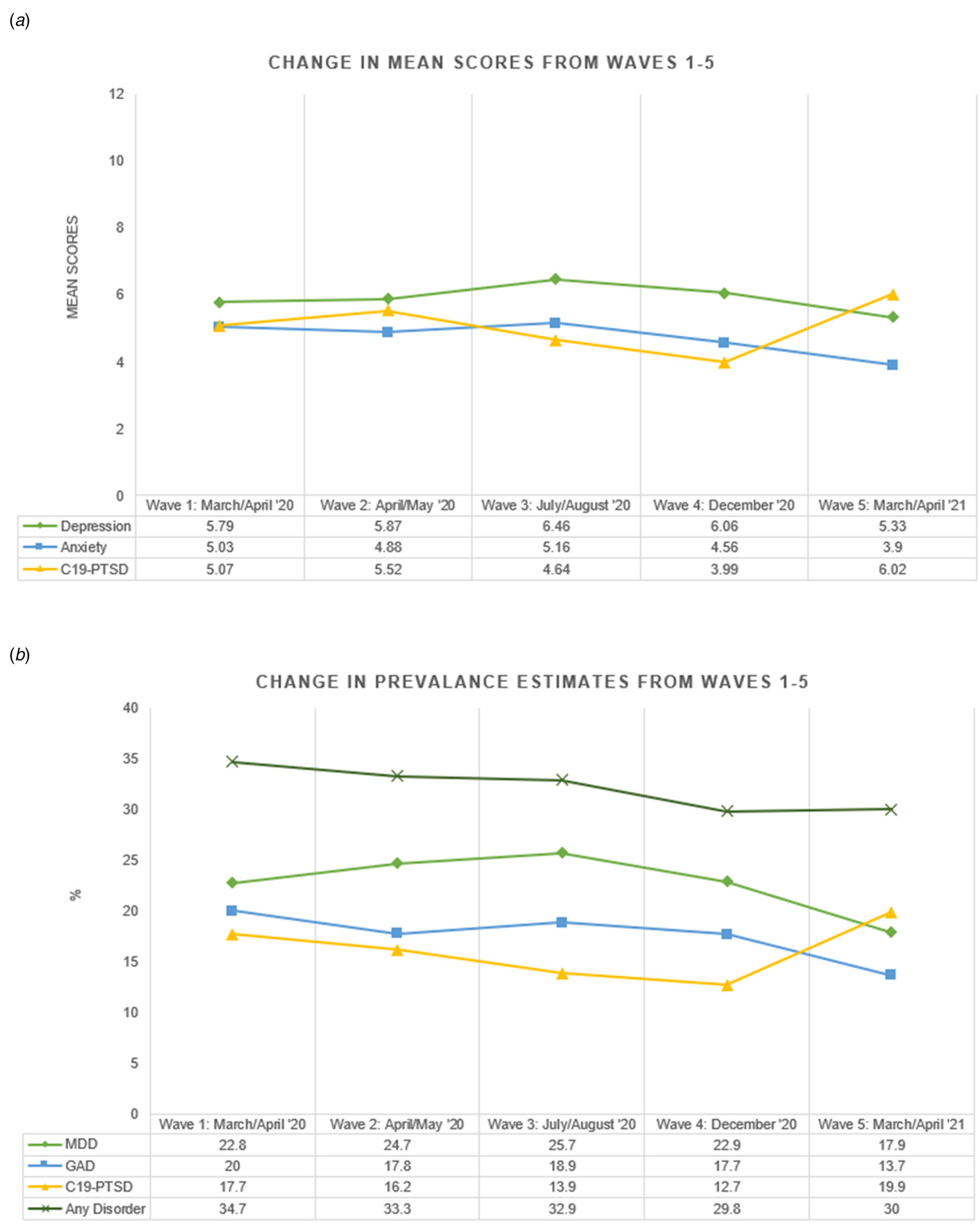

Tables containing the full set of findings regarding the longitudinal changes in the mean scores and prevalence estimates of depression, anxiety, and/or C19-PTSD can be found at https://osf.io/ekry8/. There were statistically significant changes in the means and prevalence estimates of all three variables across the five waves (see Fig. 1). Mean levels of depression were lower at Wave 5 than Wave 1 but not significantly so (d = 0.09, p = 0.063), and the proportion of people meeting the criteria for depression at W5 was 4.9% points lower than at W1 (p = 0.018). Mean levels of anxiety were significantly lower at W5 than W1 (d = 0.26, p < 0.001), and the proportion of people meeting the criteria for anxiety at W5 was 6.3% points lower than at W1 (p < 0.001). Mean levels of C19-PTSD were significantly higher at W5 than W1 (d = 0.19, p < 0.001), and although the proportion of people meeting the criteria for C19-PTSD increased by 2.2% points from W1 to W5, the difference was not significant (p = 0.248). Overall, 34.7% of people met the criteria for depression, anxiety, or C19-PTSD at W1 and this dropped by 4.7% points to 30.0% by W5 (p = 0.033).

Fig. 1. Longitudinal change in means and prevalence estimates during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Together these findings provide no evidence of an overall increase in mental health problems in the general adult population of Ireland during the first year of the pandemic, and to the contrary, suggest that there was a small overall decrease in mental health problems driven by declines in depression and anxiety. These findings are consistent with results from multiple large-scale longitudinal studies from UK (Fancourt, Steptoe, & Bu, Reference Fancourt, Steptoe and Bu2021; Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, Butter, McBride, Murphy, Gibson-Miller, Hartman and Bentall2021), and meta-analyses of pre-post pandemic changes in mental health symptoms (Prati & Mancini, Reference Prati and Mancini2021; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Sutin, Daly and Jones2021). These findings stand in stark contradiction to concerns expressed at the outset of the pandemic that there would be a marked increase in mental health problems in the general population (Campion, Javed, Sartorius, & Marmot, Reference Campion, Javed, Sartorius and Marmot2020).

Financial support

This research received funding from the Health Research Board and the Irish Research Council under the COVID-19 Pandemic Rapid Response Funding Call [COV19-2020-025].

Conflict of interest

None.