Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide, with more than 700 000 people committing suicide in 2019, accounting for 1.3% of all deaths in 2019 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Approximately 58% of suicides occur among individuals aged under 50 years, posing a significant global public health problem with implications for the working population (WHO, 2021). Specifically, the suicide rate in South Korea is exceptionally high at 24.1 per 100 000 population, while the average suicide rate among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is 11.0 (OECD, 2023).

The causes of suicide are multifaceted, involving psychiatric, biological, social, environmental, and demographic factors (Farooq, Tunmore, Wajid Ali, & Ayub, Reference Farooq, Tunmore, Wajid Ali and Ayub2021; Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016). Among them, unemployment is an important social factor. Several studies, including one conducted in South Korea, have reported an association between unemployment and suicide (Blakely, Collings, & Atkinson, Reference Blakely, Collings and Atkinson2003; Nordt, Warnke, Seifritz, & Kawohl, Reference Nordt, Warnke, Seifritz and Kawohl2015; Yoon, Jung, Choi, & Kang, Reference Yoon, Jung, Choi and Kang2019).

Studies have suggested that the association between unemployment and suicide stems from mutual risk factors, such as mental illnesses (Milner, Page, & LaMontagne, Reference Milner, Page and LaMontagne2014; Mortensen, Agerbo, Erikson, Qin, & Westergaard-Nielsen, Reference Mortensen, Agerbo, Erikson, Qin and Westergaard-Nielsen2000). However, there is also evidence suggesting that unemployment causes suicide. A recent study conducted in Australia used 13 years of data and found that the association between unemployment and suicide is causal (Skinner, Osgood, Occhipinti, Song, & Hickie, Reference Skinner, Osgood, Occhipinti, Song and Hickie2023). According to studies, unemployment can lead to suicide through various pathways, such as impaired mental health, increased psychological distress (Daly & Delaney, Reference Daly and Delaney2013; Paul & Moser, Reference Paul and Moser2009; Yoo et al., Reference Yoo, Park, Jang, Kwon, Kim, Cho and Park2016; Yoon, Kim, Park, & Kim, Reference Yoon, Kim, Park and Kim2017), financial stress, which is also related to mental illnesses (Ridley, Rao, Schilbach, & Patel, Reference Ridley, Rao, Schilbach and Patel2020), and social isolation (Pohlan, Reference Pohlan2019).

However, it is also possible that the impact of unemployment accumulates over time. A previous study found that the number of unemployment spells is related to decreased quality of life and satisfaction, showing that unemployment has a scarring effect (Mousteri, Daly, & Delaney, Reference Mousteri, Daly and Delaney2018). Similarly, another study reported that adults experiencing fluctuations between different employment statuses are more prone to suicidal thoughts than consistently unstably employed or unemployed individuals (Kim, Ki, Choi, & Song, Reference Kim, Ki, Choi and Song2019). Studies have also shown a cumulative effect of unemployment on mental health and acute myocardial infarction (Dupre, George, Liu, & Peterson, Reference Dupre, George, Liu and Peterson2012; Strandh, Winefield, Nilsson, & Hammarström, Reference Strandh, Winefield, Nilsson and Hammarström2014).

Based on the existing evidence, it is plausible to hypothesize that the risk of suicide attributable to unemployment increases as the number of unemployment spells increases. However, to the best of our knowledge, research remains scant on the impact of the number of unemployment spells on suicide. Therefore, this study investigates how unemployment experiences affect suicide mortality and whether the effect varies based on the number of unemployment spells using two years of nationwide data from a country with one of the highest suicide rates.

Material and methods

Data source

We utilized data from Statistics Korea (the National Statistical Office of South Korea) and the Korean Employment Information Service (KEIS) for the years 2018 and 2019. Initially, we collected information on the number of deaths by cause, along with mid-year population figures categorized by sex and age (grouped into five-year intervals) from Statistics Korea. Subsequently, we obtained data on the total number of workers for each year, categorized by employment and unemployment history, from KEIS. Finally, we merged the datasets from both institutions to gather information about the employment history and cause of death of individuals who died during this period and had a record of employment.

Definition of a worker and the number of unemployment spells

We defined a ‘worker’ as anyone with an employment history in each calendar year of 2018 or 2019. We used workers' employment records to determine the number of unemployment spells that occurred over the past five years. For the total worker population, we analyzed employment records from the preceding five calendar years (from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2018, for the 2018 dataset; from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019, for the 2019 dataset). For workers who died during this period, we analyzed employment records from the five years leading up to their date of death. The number of unemployment spells was categorized as zero, one, two, three, and four or more in the past five years. The analysis was limited to workers aged 25–64 years – generally considered the working population in Korea – and five years of employment history was evaluated.

Cause of death

Statistics Korea provides information on the causes of death based on the 8th revision of the Korean Classification of Diseases, which is aligned with the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases. For this study, the focus was on suicides, categorized as intentional self-harm under the external cause of morbidity and mortality. To distinguish suicides from other external causes, the category was split into two: suicide (X60–X84) and external causes other than suicide (U12 and V01–Y89, except for X60–X84). We also identified four other leading causes of death that accounted for more than 5% of the total deaths: neoplasms (C00–D48), diseases of the circulatory system (I00–I99), diseases of the digestive system (K00–K92), and symptoms and signs not classified elsewhere (R00–R99). All remaining causes were grouped as ‘others combined.’

Statistical analysis

We calculated crude mortality rates per 100 000 people for the general population, total workers, and workers stratified by the number of unemployment spells. To assess the impact of unemployment on mortality, indirect standardization was employed, using the general population as the reference group to compute standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) according to the number of unemployment spells. Proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) and 95% CIs were also calculated according to the number of unemployment spells, using the distribution of mortality in the general population as the reference. Furthermore, stratified analyses were conducted by sex and age group (25–44 and 45–64 years) for SMR and PMR analyses to explore potential differences in mortality rates among the subgroups. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (AJOUIRB-EXP-2021-149, AJOUIRB-EXP-2022-180). Informed consent was waived because the data we obtained were not individual level.

Results

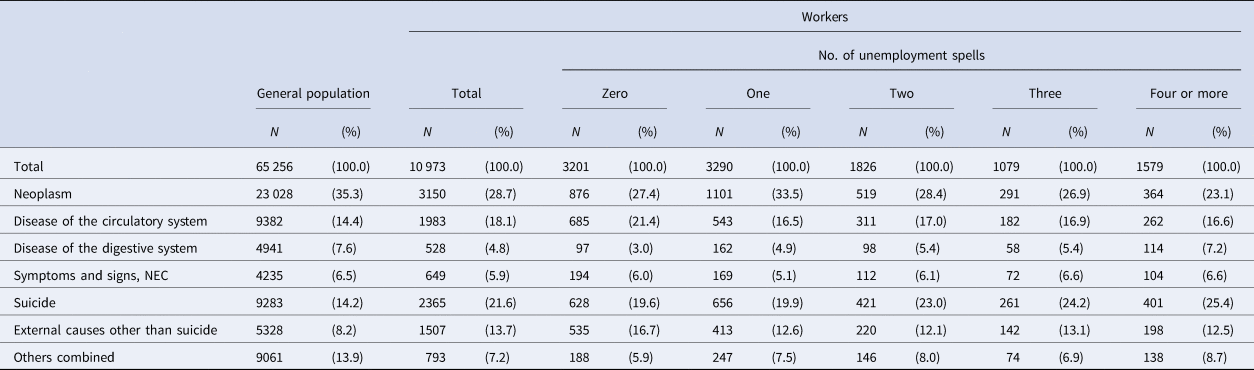

In Korea, an average of 65 256 deaths occurred annually from 2018 to 2019 among the general population aged 25–64 years (10 973 workers). Neoplasm was the leading cause of death for the general population (35.3%) and workers (28.7%). However, suicide was more common among workers (21.6%) than among the general population, where it was the third most common cause of death (14.2%). Diseases of the circulatory system were the second most common cause of death in the general population (14.4%) and third most common cause among workers (18.1%). The proportion of suicide increased with the number of unemployment spells, with proportions of 19.6% and 25.4% in workers with no unemployment spells and four or more unemployment spells, respectively. The distribution of leading causes of death is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of leading causes of death among individuals aged 25–64 years in the general population and workers, 2018–2019

Abbreviation: NEC, not elsewhere classified.

All numbers are the averages of 2018 and 2019. The totals may not correspond to the sum of separate figures owing to approximation.

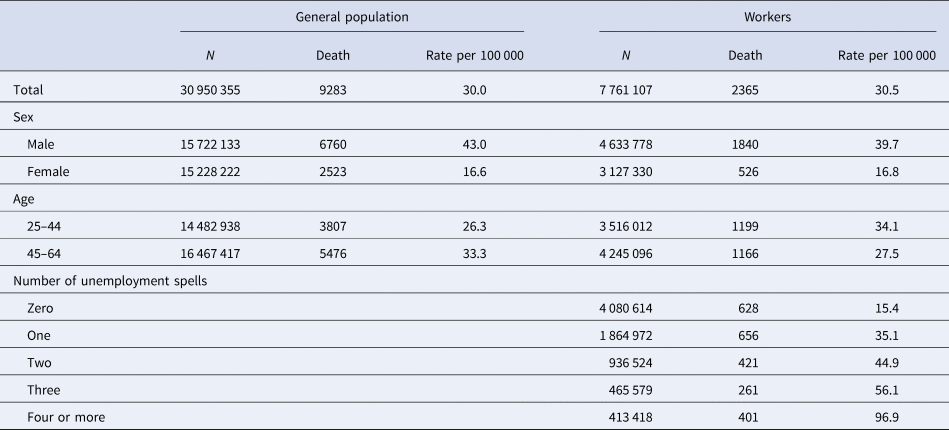

Table 2 presents the total number of individuals in the general population and workers based on sex, age, number of unemployment spells, and suicide mortality rates per 100 000 people. The general population and workers had similar suicide mortality rates (30.0 and 30.5, respectively). Men had a higher suicide mortality rate than women in both groups. In the general population, the older age group (45–64) had a higher suicide mortality rate (33.3) than the younger age group (25–44; 26.3). However, younger workers had a higher suicide mortality rate (34.1) than older workers. The suicide mortality rate increased gradually with the increase in the number of unemployment spells – the lowest rate was observed in the group with no unemployment spells (15.4) and the highest in the group with four or more unemployment spells (96.9). Stratified analyses by sex and age group showed similar results, demonstrating a consistent pattern wherein the crude suicide mortality rate increased with the increase in the number of unemployment spells across both sexes and age groups (online Supplementary Table).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and crude mortality rates for suicide among the general population and workers aged 25–64 years, 2018–2019

All numbers are the averages of 2018 and 2019. The totals may not correspond to the sum of separate figures owing to approximation.

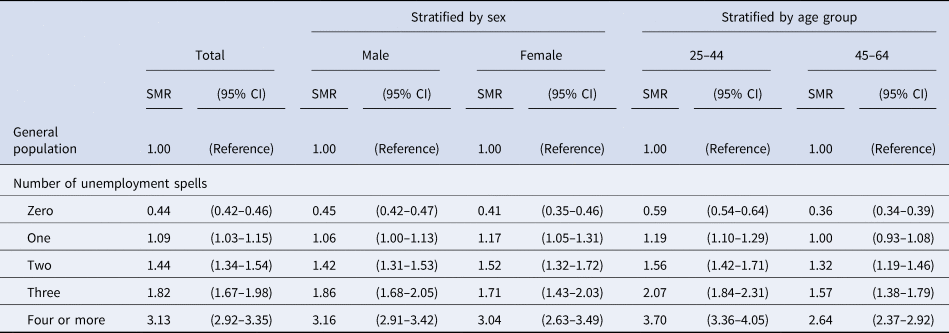

Table 3 presents the results of comparing SMRs for suicide among workers aged 25–64 years and the general population based on the number of unemployment spells. Among total workers, the group with no unemployment spells displayed a significantly lower SMR than the general population (SMR: 0.44, 95% CI 0.42–0.46), whereas all other groups exhibited significantly higher SMRs – the highest SMR was observed in the group with four or more unemployment spells (3.13; 2.92–3.35). These findings were consistent across all subgroup analyses. While men exhibited a crude mortality rate exceeding that of women by more than 2-fold, the SMRs according to the number of unemployment spells remained similar across both sexes. However, the SMRs among younger workers in all categories were higher compared to those of older workers. In addition, it is noteworthy that the SMRs for suicide among men and younger workers significantly increased with each increment of unemployment spell, accompanied by distinct confidence intervals.

Table 3. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for suicide among workers aged 25–64 years compared to the general population according to the number of unemployment spells in the past five years, 2018–2019

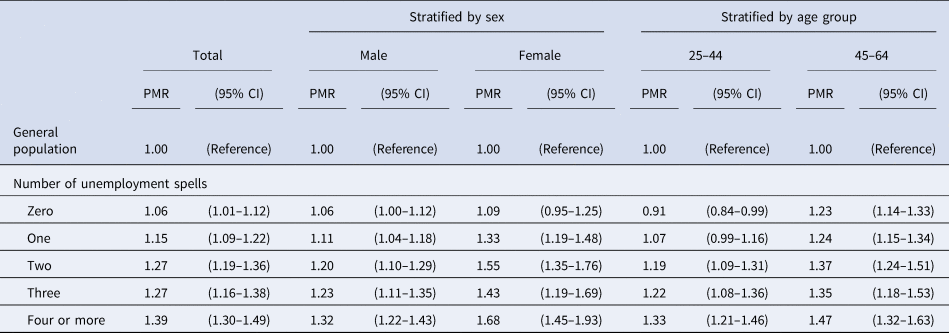

Table 4 presents the results of comparing PMRs among workers aged 25–64 years and the general population based on the number of unemployment spells. All worker groups exhibited significantly higher PMRs than the general population. As the number of unemployment spells increased, PMRs also increased – the highest rate was observed in the group with four or more unemployment spells (1.39; 1.30–1.49). These results were generally consistent across the stratified analyses. However, female workers with four or more unemployment spells displayed a higher PMR (1.68; 1.45–1.93) than male workers (1.32; 1.22–1.43), and older workers with four or more unemployment spells showed a higher PMR (1.47; 1.32–1.63) than younger workers (1.33; 1.21–1.46).

Table 4. Proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) for suicide among workers aged 25–64 years compared to the general population according to the number of unemployment spells in the past five years, 2018–2019

Discussion

This study investigated the association between the number of unemployment spells and suicide mortality. Utilizing nationally representative data, we obtained mortality data for the entire workforce and compared them with the overall Korean population. The overall suicide mortality rate among workers was similar to that among the general population. However, suicide mortality rates were higher among younger workers than among older workers. We also observed a trend of increasing crude mortality rates, SMRs, and PMRs for suicide as the number of unemployment spells increased, even after stratification by sex and age, suggesting a dose-response effect of unemployment on suicide mortality. Specifically, each instance of unemployment spell, regardless of the previous number of spells, led to a significant increase in SMRs among men and younger workers.

In this study, the suicide mortality rate among men was more than twice the rate among women, which is consistent with the previous finding that the risk of suicide is generally higher among men than among women (Hawton, Reference Hawton2000). However, our finding that the suicide mortality rate was higher among young workers than among young general population or older workers is inconsistent with previous findings. Generally, individuals with jobs tend to have lower suicide rates than those who are unemployed (Blakely et al., Reference Blakely, Collings and Atkinson2003; Yur'yev, Värnik, Värnik, Sisask, & Leppik, Reference Yur'yev, Värnik, Värnik, Sisask and Leppik2012), and suicide rates typically tend to increase with age (Cheong et al., Reference Cheong, Choi, Cho, Yoon, Kim, Kim and Hwang2012; Statistics Korea, 2022). Although it is unclear, work-related risk factors for mental health, such as excessive workload, emotional labor, and job insecurity, may have a stronger impact on young workers, as they tend to experience more psychological distress due to less control and less stable positions at work (Hybels, Blazer, Eagle, & Proeschold-Bell, Reference Hybels, Blazer, Eagle and Proeschold-Bell2022).

We found that the suicide mortality rate was higher among individuals who experienced just one unemployment spell than among the general population. Notably, the suicide rate increased as the number of unemployment spells increased. These observations suggest that distress associated with unemployment may accumulate over time and intensify the risk of suicide. Our SMR analyses, standardized by sex and age group, consistently supported these results. Compared to the suicide rate among cancer patients in South Korea, which is reported to be twice as high as that of the general population (Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Shin, Cho, Park, Won and Yun2010), the suicide mortality rate among workers with four or more unemployment spells, which is more than three times higher, suggests that repeated experiences of unemployment are profoundly distressing and traumatizing. Stratified analyses by sex and age also produced similar results, indicating that the cumulative experience of unemployment is a vulnerability for suicide across all demographic groups.

The mechanisms contributing to a higher risk of suicide among the unemployed than the employed include the direct stress of unemployment, loss of work-related identity and relationships, and financial strain (Wanberg, Reference Wanberg2012). Increased mental stress has also been objectively reported in studies that have shown an increase in cortisol levels after unemployment (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Egger, Barth, Winker, Osterode, Kundi and Ruediger2006). In other words, the impact of unemployment goes beyond just losing the job; it involves losing the value of work and job rewards (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg1977). This, in turn, leads to damaged self-esteem, a loss of motivation, and depression, all contributing to an increase in suicidal tendencies.

Additional hypotheses explaining the rise in suicide mortality rates associated with an increased number of unemployment spells include the ‘scarring effect’, where early unemployment can result in negative long-term outcomes, and the ‘discouraged worker effect’, wherein learned helplessness, lack of self-esteem, and fear of rejection contribute to a reluctance to actively finding and returning to work. Past experiences of unemployment can have long-lasting effects, diminishing the well-being of individuals in the workforce (Clark, Georgellis, & Sanfey, Reference Clark, Georgellis and Sanfey2001). According to human capital theory, experiencing repeated unemployment diminishes future labor skills, placing individuals at a disadvantage in the job market (Becker, Reference Becker2009; Manzoni & Mooi-Reci, Reference Manzoni and Mooi-Reci2020). Even if they manage to secure employment, they are more likely to be limited to low-status, low-paying jobs, perpetuating a cycle of precarious employment (Gangl, Reference Gangl2006). This detrimental feedback loop leads to workers developing a sense of failure, resulting in a tenfold increase in suicidal ideation (Korea Suicide Prevention Center, 2020).

In contrast, workers without unemployment spells showed a significantly lower suicide mortality rate than the general population. This is a natural consequence of having a secure income and can be explained by the healthy worker effect – people with good mental health are more likely to stay employed (Li & Sung, Reference Li and Sung1999). Additionally, work itself may have a positive effect on an individual's mental health, for example, through a sense of accomplishment (Satuf et al., Reference Satuf, Monteiro, Pereira, Esgalhado, Marina Afonso and Loureiro2018).

The higher PMR in workers than in the general population suggests that they are an important group in terms of their relative contribution to suicide. The proportion of suicides among all causes of death in workers was approximately 1.5 times higher than that in the general population, while the proportions of cancer or chronic diseases, which often lead individuals to stop working due to reduced work capacity or the need for treatment, were comparatively lower. Nevertheless, PMRs for suicide demonstrated an increase as the number of unemployment spells increased, adding support to the finding that the cumulative stress associated with unemployment heightens the risk of suicide. Among workers with four or more unemployment spells, suicide surpassed cancer as the primary cause of death. Therefore, this group requires enhanced care and vigilant monitoring.

While our primary focus was on elucidating the mechanism through which unemployment experiences impact suicide mortality rates via the deterioration of mental health, it is also well-known that mental health influences both employment status and suicide mortality concurrently (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Liu, Li, Tsai, Chen and Kuo2023; Dobson, Vigod, Mustard, & Smith, Reference Dobson, Vigod, Mustard and Smith2021; Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Arffman, Lumme, Suokas, Pirkola and Böckerman2020; Milner et al., Reference Milner, Page and LaMontagne2014). Although mental disorders can directly contribute to suicide, there are suggested pathways through which mental disorders impact the risk of suicide via change in employment, which may result in economic difficulty. Individuals with mental health issues are often marginalized from the employment market, leading to an increased risk of unemployment. Even if they manage to maintain employment, their incomes are more likely to be declined (Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Arffman, Lumme, Suokas, Pirkola and Böckerman2020; Hynek, Hollander, Liefbroer, Hauge, & Straiton, Reference Hynek, Hollander, Liefbroer, Hauge and Straiton2022; Olesen, Butterworth, Leach, Kelaher, & Pirkis, Reference Olesen, Butterworth, Leach, Kelaher and Pirkis2013). Several potential causes contribute to their unemployment. Among these, disability stands out as a significant factor. However, it is important to recognize that stigma and discrimination, which are also direct causes of suicide, also play pivotal roles in the unemployment experienced by individuals with mental health issues (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Green, Davies, Demou, Howe, Harrison and Munafò2022; Sharac, Mccrone, Clement, & Thornicroft, Reference Sharac, Mccrone, Clement and Thornicroft2010; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose and Henderson2016).

In light of the findings from existing literature, it is plausible to interpret the result of our study as indicating that individuals with pre-existing mental health problems, who are already at a high risk for suicide, experienced recurrent unemployment due to their health condition. Conversely, the assumption that repeated unemployment may impact workers' mental health, thereby increasing the risk of suicide, as hypothesized study, is also plausible. To overcome this limitation, previous studies examining the causal relationship between employment status and suicide utilized longitudinal study designs that ascertain temporal relationships or controlled mental health-related factors (Milner et al., Reference Milner, Page and LaMontagne2014; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Osgood, Occhipinti, Song and Hickie2023). However, it is important to note that our study was a cross-sectional study. Furthermore, although we collected individual data on age, sex, employment history, and suicide deaths, we were unable to obtain personal characteristics known to influence suicide mortality, such as substance abuse, socioeconomic condition, and personal histories of mental and physical illnesses. As a consequence, our study's limitations prevented the establishment of a causal relationship between unemployment and suicide mortality, therefore, caution is needed when interpreting the results. Given that utilizing the number of unemployment spells as a risk factor for suicide is, to the authors' knowledge, a novel approach, there is a necessity for future research to employ longitudinal designs and include a broader array of personal characteristics to establish causal relationships, even though there is growing evidence suggesting that unemployment itself act as a causal factor in suicide.

There are some other limitations in this study. First, certain workers who are not covered by employment insurance, such as government employees and private school faculty members, were not included in this study. However, as of 2019, more than 90% of workers were covered by employment insurance (Korean Statistical Information Service [KOSIS], 2023), implying that this study is representative of the entire Korean workforce. Also, we were unable to determine whether unemployment was voluntary or involuntary since the cause of employment termination could not be identified in the employment insurance data. Future studies should include information on unemployment benefits as these are exclusively provided to individuals who have lost their jobs involuntarily.

Despite these limitations, this study's strengths lie in being the first study that used credible large-scale data to explore the relationship between the number of unemployment spells and suicide mortality in the context of Korea. To increase the reliability of our results and provide an objective understanding of suicide mortality among Korean workers, we used data on the causes of death from Statistics Korea. This dataset adheres to international cause-of-death classification standards, enhancing the credibility of our findings.

Effective suicide prevention requires the identification of vulnerable groups and targeted policy support. Along with precarious employment and prolonged unemployment, which are known occupational risk factors for suicide, we suggest that a high number of unemployment spells can also be a risk factor. Therefore, individuals who face repeated unemployment require not only economic support, such as unemployment benefits but also social and psychological support. This study is timely as it has implications for protecting workers' mental health amid the economic downturn and deteriorating labor market conditions triggered by the coronavirus disease pandemic. Furthermore, unemployment stress has a detrimental impact on not only mental but also physical health. Therefore, further research is necessary to investigate the impacts of the number of unemployment spells on other causes of death, as well as to examine the effects of unemployment duration on suicide rates and/or mental health outcomes. Understanding these relationships can help devise comprehensive strategies to protect and support the well-being of workers and address the complex challenges associated with unemployment and suicide prevention.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000965

Acknowledgments

We thank Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute for processing and providing the data from Statistics Korea (the National Statistical Office of South Korea) and the Korean Employment Information Service (KEIS).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute, Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (2021-OSHRI-727, 2022-OSHRI-802).

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.