Formal flexible training first became available in 1969, and was specifically aimed at women with domestic commitments. Except for some posts in Oxford, the scheme was not greatly used until 1979, when there was a focusing on senior registrar training, with a second boost in 1991 with the introduction of a new scheme for career registrars. Demand for flexible training posts is growing, with a reported increase of 30% across grades and specialties (Reference GoldbergGoldberg, 1997). It has been suggested that, nationally, 14% of psychiatrists train flexibly, although the uptake varies regionally between 3.5% and 26% (NHS Management Executive, 1993). More recent evidence suggests this figure is an underestimate: in a survey of consultant psychiatrists over 50 years of age, 16% had trained flexibly, and of these, 76% were women (Reference Mears, Kendall and KatonaMears et al, 2004). Today, it is likely that a significantly greater proportion of female consultant psychiatrists have trained flexibly.

This project builds on a survey carried out in the Thames region (Reference Etchegoyen, Stormont and GoldbergEtchegoyen et al, 2001), which found that part-time training for women in this region was largely considered satisfactory, although not without difficulties. The national study described here extends the College Research Unit’s existing workforce planning research.

Method

The questionnaire used in the Thames region study (Reference Etchegoyen, Stormont and GoldbergEtchegoyen et al, 2001) was adapted for national use. The questions covered demographics, training, quality of subsequent posts, obstacles encountered and reasons behind career choices. Throughout the questionnaire, an anchored five-point Likert scale was used to yield useable data. The anchor points were 1 for no influence/not at all, 5 very influential/a great deal.

As no central record of flexible training exists, a list of all practising female consultants in the UK (n=1689) was obtained from the registrations department of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. All individuals on the list were sent the questionnaire and asked to complete and return it if they had trained flexibly, and to return only the front page if they had not. Analyses were carried out on the data collected using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 11.5).

Results

Three hundred useable questionnaires were returned, giving an adjusted response rate of 47.3% (taking account of non-flexibly trained respondents).

Demographics and training

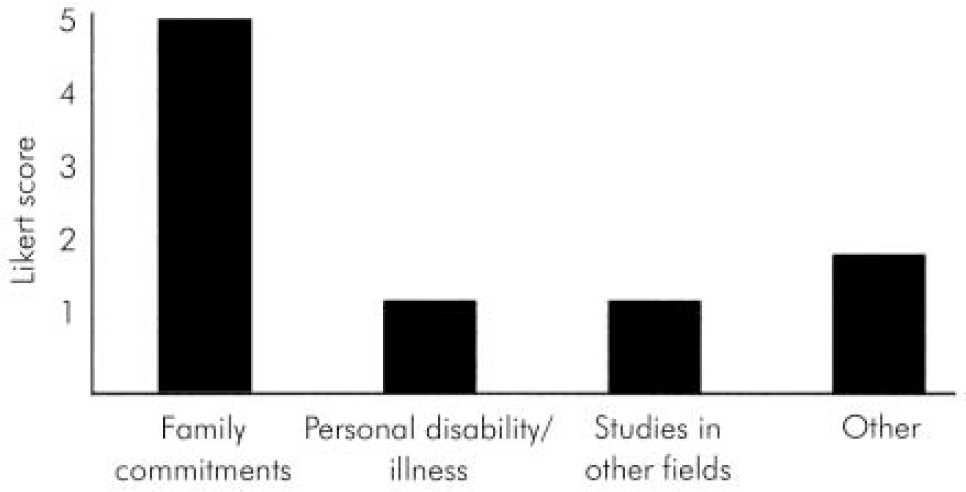

Overwhelmingly, family commitments were reported as the key factor in the decision to train flexibly. Figure 1 shows the mean scores for each factor, using the five-point scale described above. Respondents were satisfied that their training had equipped them for the responsibilities they found after accreditation (mean score 4.4, s.d. 0.86), and that flexible training had enabled them to obtain the job of their choice (mean 4.2, s.d. 1.10) and had not hindered their clinical progress (mean 1.5, s.d. 0.96). However, respondents thought that flexible training had had a slightly negative influence upon academic progress (mean 2.4, s.d. 1.47).

Fig. 1. Factors influencing the decision to train flexibly.

First post after accreditation

The great majority of the sample (95%) obtained a substantive post in psychiatry after accreditation, and for almost all (94%) this was at consultant level. Of those responding, 43% moved into full-time posts (n=127), a majority (53%, n=155) worked in part-time posts, 4% in job shares; 83% (n=248) reported obtaining their first choice of working pattern (although for those in full-time posts, this figure drops to 73%), with family commitments identified as the most important factor influencing that choice (mean 4.3, s.d. 1.24). The average number of sessions worked in the first job for part-timers was 7.0 (s.d. 1.8) and for all respondents it was 8.6 (s.d. 2.4). Respondents were generally satisfied with their first post (mean score 3.8, s.d. 1.12), and less than satisfied with support from management (mean 2.9, s.d. 1.16).

Respondents were asked to indicate if they had experienced any of a list of potential problems in their first post. These are shown, compared with problems encountered in subsequent posts, in Table 1.

Table 1. Problems encountered in first and second substantive posts

| Problem | Post 1 n (%) | Post 2 n (%) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive workload | 199 (66) | 60 (61) | -5 |

| Problems with protected study sessions per week | 155 (52) | 48 (49) | -3 |

| Lack of CPD time | 133 (44) | 45 (46) | +2 |

| Lack of administrative support | 91 (30) | 31 (32) | +2 |

| Lack of junior staff | 136 (45) | 42 (43) | -3 |

| Other | 74 (25) | 28 (29) | +3 |

| None of the above | 33 (11) | 12 (13) | +2 |

Subsequent posts

Approximately a third (n=101) of the sample had moved into a second post, with almost all (97%) entering a consultant post, including 2% gaining an academic position. Of these, 54% were full-time posts, 43% part-time and 3% job-sharing, with an average number of sessions worked of 9 (s.d. 2.6). The reasons for leaving the first post are listed in Table 2. Respondents were generally satisfied with their second post (mean 3.8, s.d. 1.18), and with the support from management (mean 3.1, s.d. 1.35). Problems compared with those seen in the first substantive post are given in Table 1.

Table 2. Reason for leaving first substantive post (n=101)

| Reason | Response n (%) |

|---|---|

| Obtained a better job | 37 (37) |

| More children | 2 (2) |

| Lack of job satisfaction | 23 (23) |

| First job too stressful | 33 (33) |

| Difficulties with management | 22 (22) |

| Other | 56 (56) |

Part-time v. full-time working

Flexibly trained consultants working part-time were more positive than their flexibly trained full-time colleagues about their training, although differences were not statistically significant. Part-time workers scored a higher mean on how well they felt their training had equipped them for practice (4.44 v. 4.35, NS) and that it had helped them obtain their desired job (4.26 v. 4.15, NS). They were more satisfied with their first post (3.81 v. 3.79, NS), but scored slightly more highly on how far they felt flexible training had hindered their academic (2.56 v. 2.2, NS) and clinical (1.54 v. 1.42, NS) progress.

Part-time consultants were found to be more likely to experience all of the problems listed in Table 3, apart from excessive workload.

Table 3. Problems encountered in full-time and part-time work patterns

| Problem encountered | Full-time n (%) | Part-time n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of junior staff | 55 (43) | 76 (49) |

| Lack of administrative support | 38 (30) | 48 (31) |

| Problems with protected study sessions per week | 64 (50) | 84 (54) |

| Lack of CPD time | 51 (40) | 76 (49) |

| Excessive workload | 94 (74) | 98 (63) |

Discussion

There are limitations to this study. With insufficient data to permit sampling of all flexibly trained psychiatrists nationally, the questionnaire form was sent to all female consultant psychiatrists. Although few men choose to train flexibly, representing only 3% of flexible trainees in one region (Reference Etchegoyen, Stormont and GoldbergEtchegoyen et al, 2001), clearly our survey only addresses the experience of flexibly trained women. A retrospective sample was chosen, because the operational difficulties of identifying a national sample of those currently in flexible training were prohibitive. Finally, we have been unable to trace the potentially important group of flexibly trained individuals who did not progress to consultant status or who had left psychiatry altogether.

Flexible training is an increasingly important route for those who – for whatever reason – do not have enough time to take part in full-time training. Flexibly trained psychiatrists have been found to outperform their full-time colleagues in terms of how quickly they gain College membership (assessed by number of examination attempts), and also gain experience in other specialties prior to psychiatry (Reference Herzberg and GoldbergHerzberg & Goldberg, 1999). This, coupled with a reported increase of 30% in demand for flexible training posts across specialties (Reference GoldbergGoldberg, 1997), shows that this is a crucial group for policy-makers to recognise and encourage.

The headlines from this study are positive: flexibly trained psychiatrists feel well-equipped for their work, and do not feel that their flexibly trained status has denied them opportunities to progress (in this, our study agrees with Reference Etchegoyen, Stormont and GoldbergEtchegoyen et al, 2001).

Unsurprisingly and overwhelmingly, family reasons are primary in the decision to train flexibly. This is positive, since this route for training was originally introduced to meet the needs of people whose family commitments were preventing them from entering full-time training.

After training, over three-quarters of the sample moved into their first choice of working pattern (equally divided between full-time and part-time, the choice again largely governed by family commitments). That for nearly a quarter of those in a full-time post this was not their first choice of working pattern indicates that more and better opportunities for flexible working at consultant level are needed. This first post was reported as largely satisfying, although problems were encountered and support from management was poor. However, these issues are shared by all consultant psychiatrists, and are not confined to the flexibly trained (Reference Mears, Kendall and KatonaMears et al, 2002). A third of respondents had moved to another consultant post, largely for reasons centred around the job itself – either the first post was unsatisfactory in some way, or a better opportunity presented itself.

Although the results are not statistically significant, a tendency emerges that consultants in part-time posts have a more positive image of their training, although they are more likely to feel it had hindered their academic career progress. Data also suggest (although again not with statistical significance) that part-time consultants are encountering problems more frequently than their full-time counterparts, with the notable exception of excessive workload. This might lead to a hypothesis that those in part-time posts tend to be more skilled at managing their time.

In summary, flexible training is being taken up by those whose family commitments are preventing them from training full-time, which is appropriate, since this is its primary purpose. Concerns that training flexibly might cause problems for those who use this route have been largely undermined by this study. Findings also suggest, however, that women who train flexibly believe that this route might hinder academic progression, and this may account, at least in part, for the underrepresentation of women in academic psychiatry (Reference Killaspy, Johnson and LivingstonKillaspy et al, 2003). Flexibly trained consultants do face problems with their work, but these are mirrored by those faced by their non-flexibly trained peers.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.