The COVID-19 pandemic triggered rapid transformations across the globe. Probably no other event in the past 50 years has changed the working environment more comprehensively. When the pandemic started in February and March of 2020, university campuses all over the globe shut down in less than a week. Most remained closed or had heavily restricted access for almost two years, depending on the country and the city. Overnight online teaching replaced in-person instruction; all professional and student interactions moved to Zoom, Teams, or Skype; academic conferences either did not take place or moved to an online format; and field research became almost impossible. In addition, contact restrictions, lockdowns, curfews, and homeschooling were unprecedented challenges for many people, especially members of the academic community who had small children (Del Boca et al. Reference Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta and Rossi2020). It is important to note that even in normal times women bear the greatest burden of childcare, social care for older people, and general household tasks. The COVID-19 pandemic quickly amplified these disparities (Ohlbrecht and Jellen Reference Ohlbrecht and Jellen2021; Yerkes et al. Reference Yerkes, André, Remery, Salin, Hakovirta and van Gerven2022). Discussions emerged in many sectors, including academia, about specific ways that the pandemic was impacting professional lives, especially those of women. Given the acute pressure to publish in most higher-education institutions, it is important to evaluate the effect that the pandemic had on this central aspect of scholarly careers.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: A CRITICAL JUNCTURE IN THE PUBLICATION LANDSCAPE?

Collier and Collier (Reference Collier and Collier1991, 27) defined a “critical juncture” as one of those events that “establish[ed] certain directions of change and foreclose[d] others in a way that shape[d] politics for years.” The question asked in this symposium is: Was the COVID-19 pandemic such a critical juncture or watershed event when it comes to publishing patterns in political science?

Theoretically, we have reasons to believe that the pandemic could have brought tremendous change into the political science publication landscape. For example, we would anticipate that the pandemic took an emotional and physical toll on many colleagues through changes in work practices and interrelated major impacts on domestic lives. Did these transformations lead to a sharp decline in journal submissions? Many journals reported challenges in securing reviewers for manuscripts before the COVID-19 pandemic. Did the transformed work and home lives of scholars intensify this challenge? Crucially, given that we know that the effects of the pandemic were not gender neutral, should we also expect a widening of the gap in gender inequalities in publishing?

To address these questions, we convened a panel of journal editors at the 2022 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Montreal. We selected journals from across the discipline. We first approached the American Political Science Review (APSR) because it is a major generalist journal. APSR also is the flagship journal of our discipline and thus well placed to identify changes in publication patterns. To reflect different subfields of political science, we then selected three major subfield journals that publish on distinct topics in political science: Political Behavior, Politics & Gender, and Politics and Religion. We also included a discussion of data from our journal, the International Political Science Review (IPSR), to this symposium’s introduction to complement analyses from the other journals. IPSR also is a generalist journal but it has a particularly broad global authorship base.

These four journals also vary in the composition of their editorial teams. APSR and Politics & Gender currently have all-female editorial teams. In contrast, Political Behavior has two male editors, and Politics and Religion and IPSR have a mixed editorial leadership of a male and a female editor. All of the journals are ranked highly in citation indices and all receive submissions from around the world. Combined, they provide a valuable snapshot of the discipline. This collection of symposium articles emerged from the discissions and reflections at the 2022 APSA Annual Meeting.

MAIN PUBLICATION PATTERNS PRE-AND POST-PANDEMIC IN AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW, POLITICAL BEHAVIOR, POLITICS AND RELIGION, AND POLITICS & GENDER

The data and analysis presented by the editors of the four journals strongly counter the narrative that academic careers were profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The publication patterns of the flagship journal of the discipline, APSR; the three major subfield journals, Political Behavior, Politics and Religion, and Politics & Gender; and IPSR do not confirm the critical-juncture thesis. Rather unexpectedly, the symposium contributions found relatively little change in publication patterns during the pandemic compared to previous patterns. Contrary to expectations, and across the five journals, we find that—if anything—there was an increase in articles submitted in the first year of the pandemic. In 2021, submission rates declined to pre–COVID-19 levels.

The fact that female scholars publish less than their male counterparts is a well-established finding, not only in political science (Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Horiuchi, Htun and Samuels2020) but also across disciplines. Before the pandemic, there were important signs that this might be changing (Reidy and Stockemer Reference Reidy and StockemerForthcoming). As the pandemic continued, initial evidence presented in the medical sciences that submissions from female scholars had fallen sharply (Clark Reference Clark2023) caused serious alarm across different fields. Many colleagues asked whether the COVID-19 pandemic was likely to be a major setback for achieving gender equality in the publishing world. Had it reversed the positive improvements observed before the pandemic and potentially entrenched inequality even further? Fortunately, for the discipline, we did not find support for this thesis. Whereas two of the journals (i.e., Political Behavior and Politics & Gender) observed a decline in female submissions in 2020, by 2021, this temporary decrease disappeared and the journals reported a return to incremental increases in female authorship afterwards. This finding is replicated in other disciplines (Biondi et al. Reference Biondi, Barrett, Mazzocchi, Ando, Harvey and Mallory2021).

The analysis of the four journals also provides nuance to these findings. It appears that the COVID-19 pandemic created reviewer fatigue, at least for APSR, the flagship journal of the discipline. The APSR editors reported the need to invite more reviewers per manuscript to find the required three reviewers. However, this was not a common problem among the other journals. The editors of Political Behavior, for example, reported that there was scholarly altruism with colleagues volunteering to complete additional reviewing work. Furthermore, at Politics and Religion, the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to have increased international submissions.

THE MAIN PUBLICATION PATTERNS IN International Political Science Review

Analysis of our journal, IPSR—the flagship journal of the International Political Science Association (IPSA)—adds further nuance to this discussion. This is a particularly interesting comparative case because we publish research from all areas of the discipline and from across the globe. The submission base of authors is especially diverse, with manuscripts submitted from an average of more than 60 countries annually.

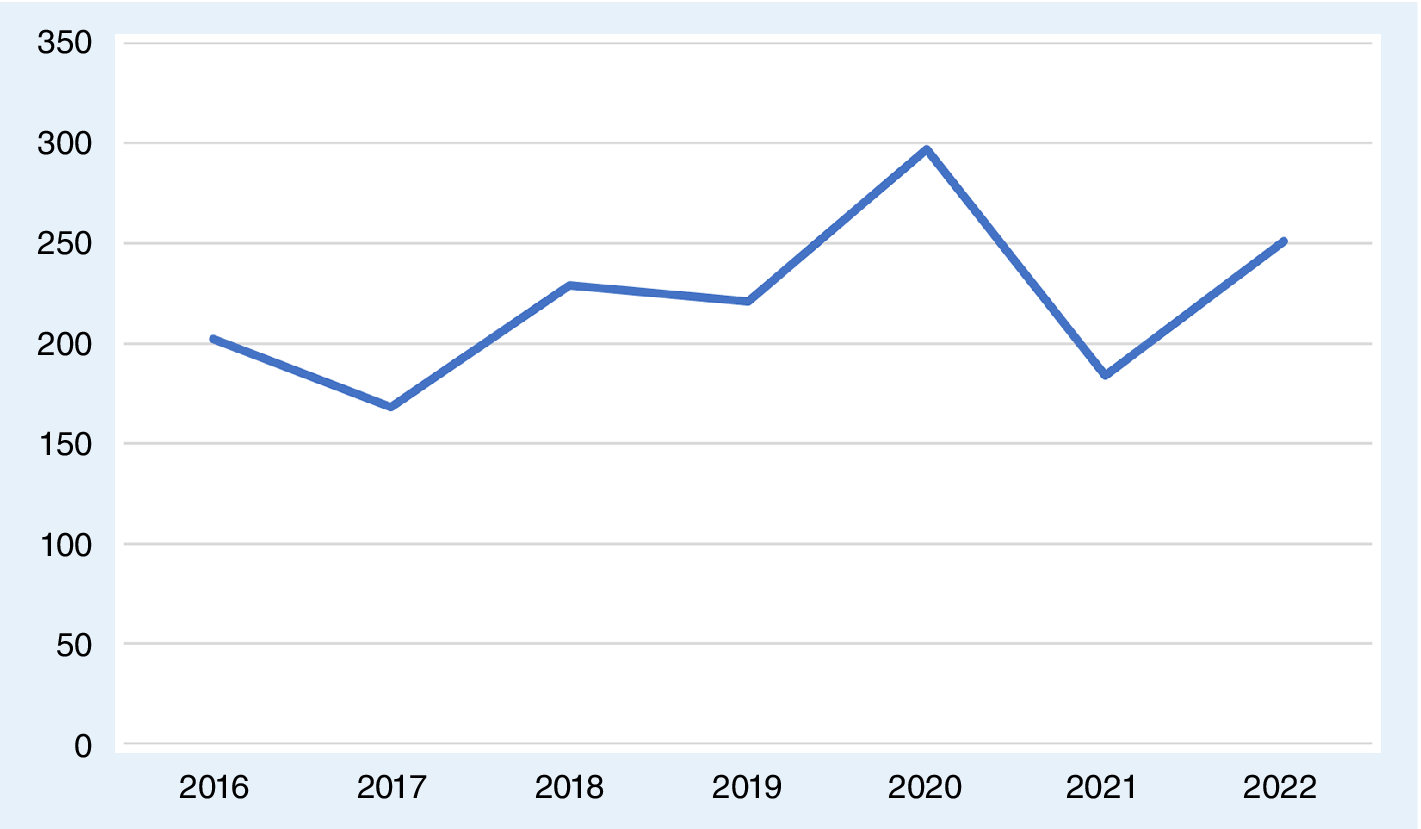

In common with the other four journals discussed in this symposium, IPSR experienced an increase in submissions in 2020. This was particularly noticeable as the year progressed, with unusual submission peaks from July to September—a period that typically would be slow for manuscript submissions due to summer holidays in the Global North. A noticeable decline in submissions in 2021 was initially cause for concern because it coincided with the World Congress of Political Science, the biannual conference of the IPSA. Congress years usually lead to a small increase in IPSR submissions, but this was not the case in 2021. However, submissions recovered strongly in 2022 (figure 1). A three-year average in submissions reveals little difference in the pandemic period compared to earlier periods.

Figure 1 IPSR Original Article Submissions by Gender 2016–2022

Sources: Scholar One, IPSR

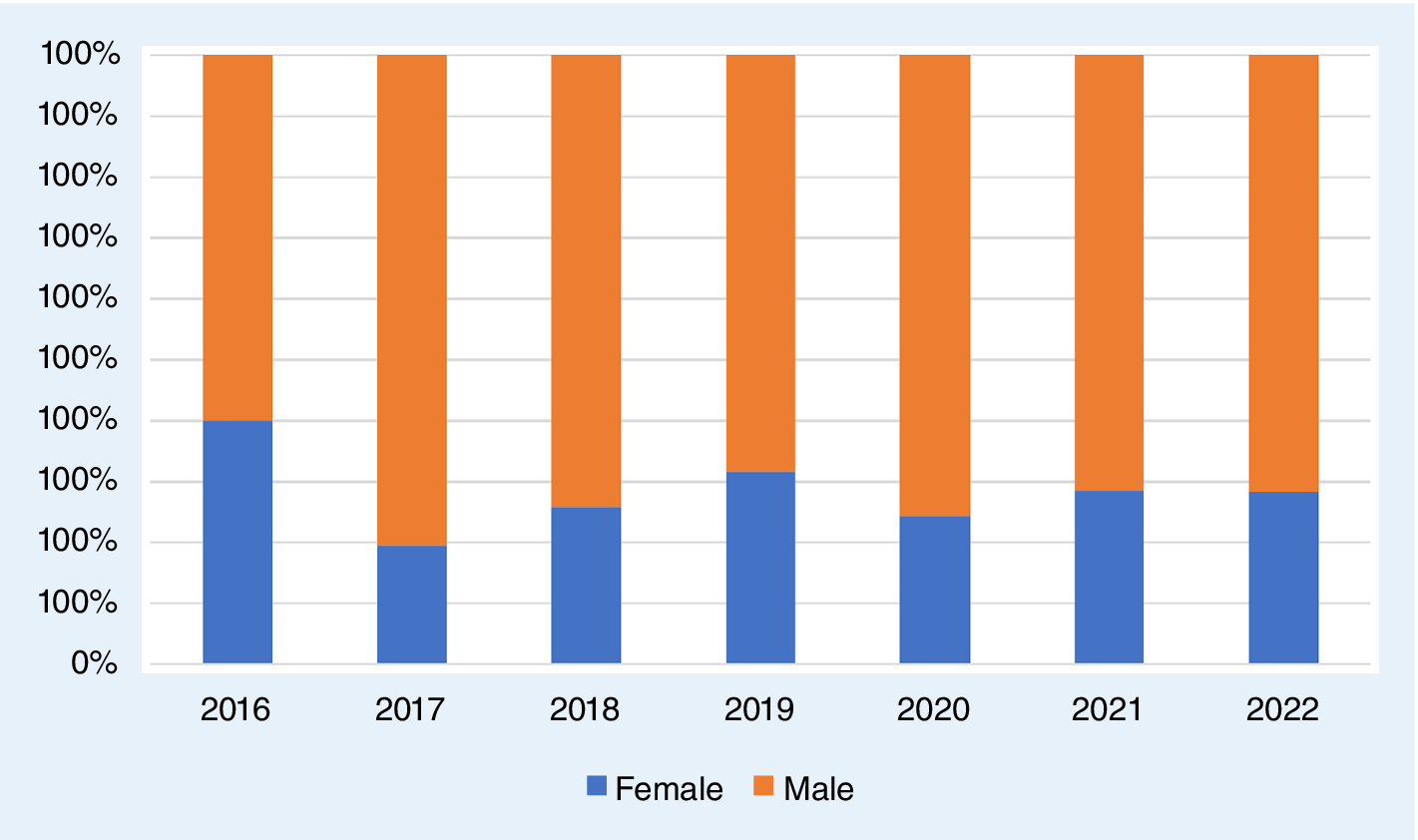

Concerning the gender balance among submitting authors (figure 2), this percentage oscillated around approximately 30% during the past decade. It is especially influenced by special issues, several of which are related to the politics and gender subdiscipline. The percentage of female authors submitting articles in 2020 decreased but nevertheless was within the normal overall range for the journal. The percentage of female authors recovered in 2021 and 2022. It is important to note that the decrease in female-authored submissions (i.e., single-author and coauthored work) was temporary; the three-year average reveals that the effect is not visible. Female authors have a higher IPSR acceptance rate than male authors. This is not unusual across the discipline, and the evidence available shows that this pattern also was not disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Female scholars continued to have their work accepted at IPSR at a higher rate than male scholars.

Figure 2 IPSR Original Article Submissions 2016–2022

Sources: Scholar One, IPSR

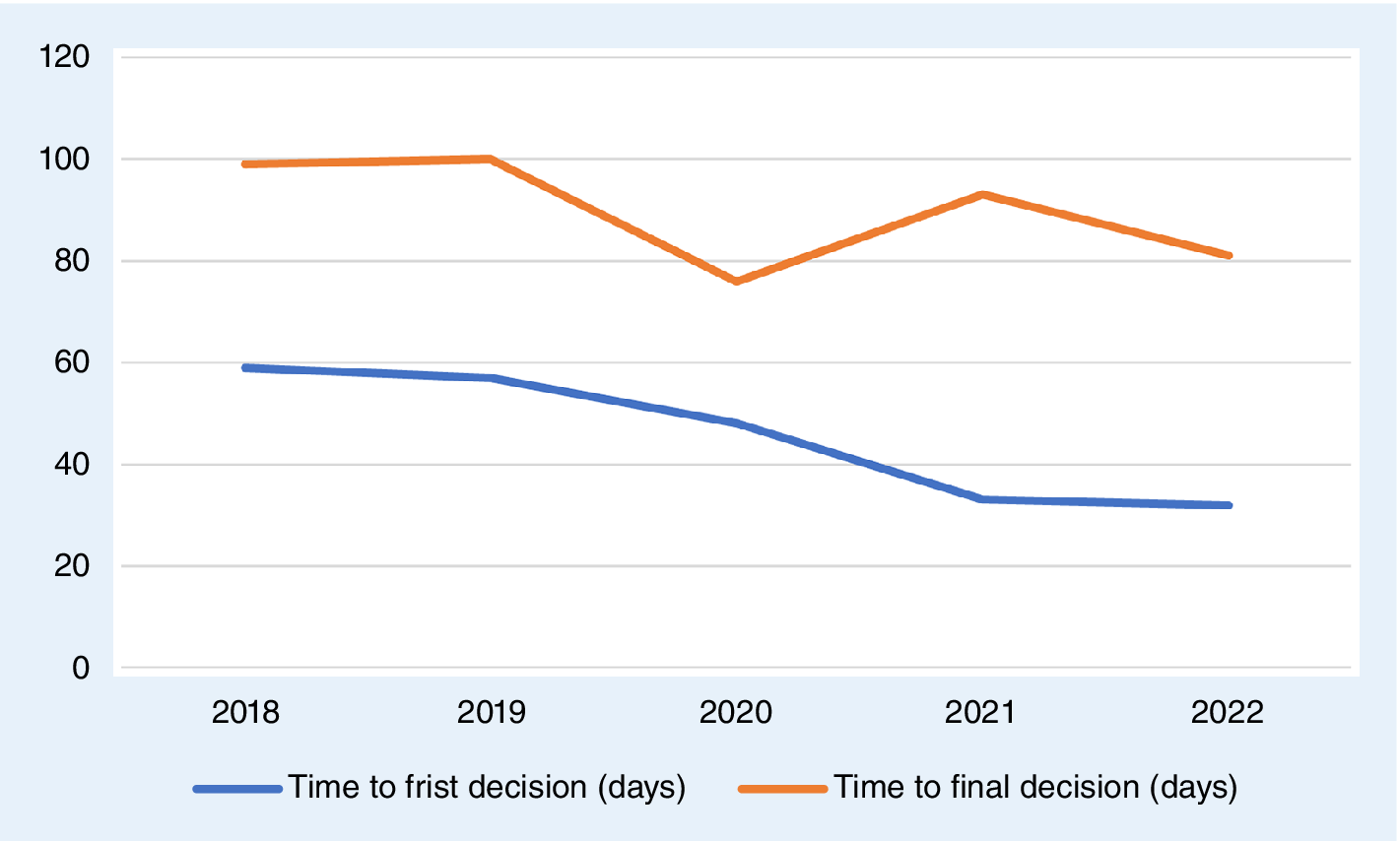

Decision making evolved during the pandemic period but not in alignment with the expectations of COVID-19 as a critical juncture (figure 3). Accelerating decision making was prioritized before the pandemic, and progress on this measure continued throughout the pandemic. On average, in 2019, it took 57 days for an author to receive a first decision (i.e., reject or revision); by 2022, this number had decreased to 32 days. Overall, the number of days is influenced heavily by desk-reject decisions. The number of days to final decision includes the review stage. In 2019, authors received a final decision after 100 days, on average. The decrease to 76 days in 2020 was influenced by a higher rate of desk rejection as well as faster reviewer turnaround times. The number of days to final decision began to increase slowly in 2021 and 2022, but it was still below the pre-pandemic average. Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic did not substantially alter decision making, including reviewer turnaround time.

Figure 3 Timing of Decisions

DISCUSSION

The initial evidence on publishing patterns in IPSR and the other four journals does not support the proposition that the COVID-19 pandemic was a major disruptive event that instituted notable change in publication patterns. If anything, the pandemic caused temporary disruption that dissipated quickly. That is, the contributions to this symposium found relatively little change in publication patterns during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic patterns. Probably the most unexpected finding that we discovered is that in the first pandemic year (2020), there was an increase in submissions across the board. Yet, other than this one-year increase, pre-pandemic publication patterns have mostly persisted.

These findings are notable because they confound the narrative of change. Moreover, they are especially important relative to perceptions about the publication contributions of female scholars. Perception matters in politics as elsewhere. If an imprecise narrative that women are disproportionately affected in the conduct of their career by certain types of crises becomes embedded, it could lead to even more unconscious bias in decisions on recruitment, promotion, and research grant awards. However, reality does not match these perceptions. Although there is some evidence of a decrease in female-authored submissions in 2020, it was temporary and within the normal variation range in authorship across the three-year period. Future research, however, could look at different types of women. For example, not all female scholars have children. Therefore, it is possible—as the editors of APSR suggest—that there is an increase in submissions by female scholars who do not have children and a decrease by those who do have children.

As pointed out by many of the editors who contributed to this symposium, the research process is a long “pipeline,” and it may be several years before the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are fully visible in our data, which is why the careful scrutiny of journal data is vitally important. Nevertheless—and despite the fact that we need more analyses of different types of women scholars—we conclude with the important point that women did not become less visible in the discipline through their publication presence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arguments to the contrary should be considered only if they are accompanied by clear evidence. Evidence—not perception—must be at the core of discussions on publication.

[W]e conclude with the important point that women did not become less visible in the discipline through their publication presence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The collection of the IPSR data was supported by funds provided by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Canada Office.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HKA2Y.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.