Introduction

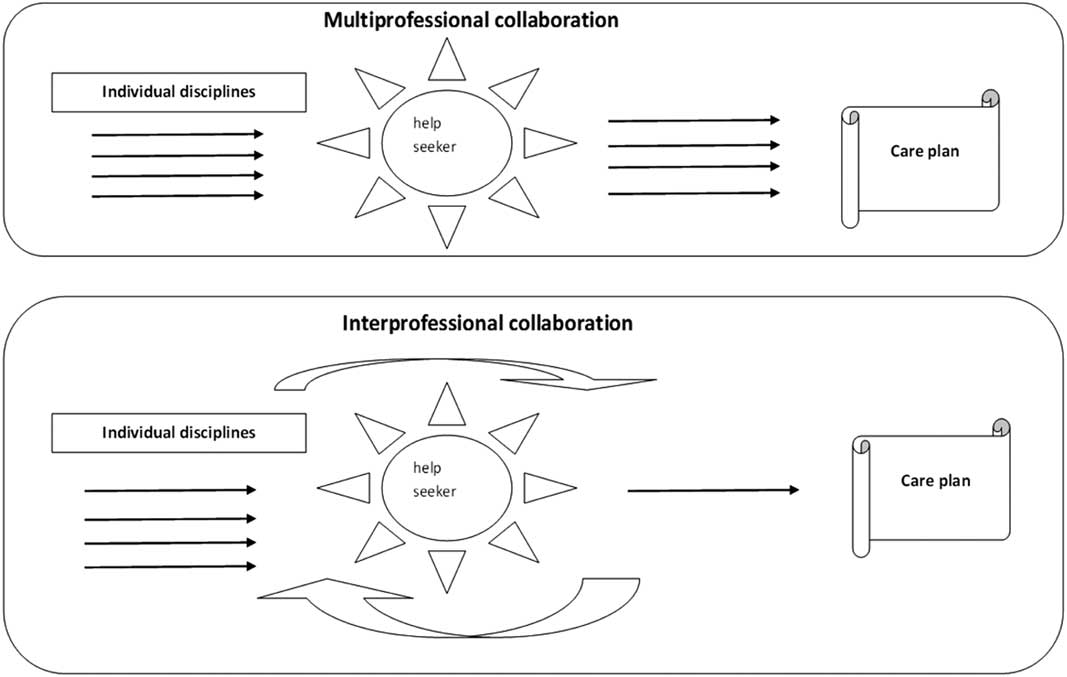

Provision of good quality of care for frail elderly requires high levels of interprofessional interventions by coordinated teamwork of healthcare professionals (Sim and Leung, Reference Sim and Leung2000). The extent to which the healthcare professionals show interprofessional collaboration and execute interventions affects the quality of the care provided (Zwarenstein et al., Reference Zwarenstein, Goldman and Reeves2009). For example, interprofessional collaboration in the care for elderly decreases fall incidences (Stenvall et al., Reference Stenvall, Olofsson, Lundstrom, Englund, Borssen, Svensson, Nyberg and Gustafson2007; Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Murray, Gillespie, Robertson, Hill, Cumming and Kerse2010; Markle-Reid et al., Reference Markle-Reid, Browne, Gafni, Roberts, Weir, Thabane and Henderson2010), the level of independence for activities of daily life (ADL) (Young et al., Reference Young, Green, Forster, Small, Lowson, Bogle, George, Heseltine, Jayasuriya and Rowe2007; Ryvicker et al., Reference Ryvicker, Feldman, Rosati, Sobolewski, Maduro and Schwartz2011) and increases patient and professionals satisfaction (Handoll et al., Reference Handoll, Cameron, Mak and Finnegan2009; Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Reider, Frey, Scharfstein, Leff, Wolff, Groves, Karm, Wegener, Marsteller and Boult2010; Berglund et al., Reference Berglund, Wilhelmson, Blomberg, Duner, Kjellgren and Hasson2013). Moreover, interprofessional interventions improve communication and collaboration to deliver good quality of care (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Reider, Frey, Scharfstein, Leff, Wolff, Groves, Karm, Wegener, Marsteller and Boult2010; Nazir et al., Reference Nazir, Unroe, Tegeler, Khan, Azar and Boustani2013). Interprofessional collaboration is considered when there is a model of working together between different healthcare providers (see Figure 1; McGill, 2001) (Yaffe et al., Reference Yaffe, Dulka and Kosberg2001; WHO, 2009; Bridges et al., Reference Bridges, Davidson, Odegard, Maki and Tomkowiak2011; Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011; CAIPE, 2014; Green and Johnson, Reference Green and Johnson2015; Tsakitzidis et al., Reference Tsakitzidis, Timmermans, Callewaert, Truijen, Meulemans and Van Royen2015). It involves the awareness of different roles in the team. The healthcare providers develop a multidisciplinary integrated and cohesive answer to the needs of the care receivers and their context. With a common vision, purposeful approach and shared responsibility, a care plan is chosen and followed-up (Vinicor, Reference Vinicor1995; Leathard, Reference Leathard2003; D’Amour et al., Reference Dagneaux, Gilard and De Lepeleire2005; WHO, 2010; Tsakitzidis and Van Royen, Reference Tsakitzidis and Van Royen2015). Integrated working and interprofessional collaboration aims to ensure continuity of care, reduce duplication and fragmentation of services and places the patient as the focus for service delivery (Amador et al., Reference Amador, Goodman, Mathie and Nicholson2016; Fleischmann et al., Reference Fleischmann, Tetzlaff, Werle, Geister, Scherer, Weyerer, Hummers-Pradier and Mueller2016). Multi-professional collaboration (see Figure 1) however is characterised by the fact that appropriate experts from different professionals handle patient’s care independently. The patient’s problems are subdivided and treated separately, with each provider responsible for his/her own area (Page, Reference Page2009). There is an urgent need to develop and test interventions that promote integrated working and address the persistent divide between health services and independent providers (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Goodman, Bunn, Victor, Dickinson, Iliffe and Froggatt2011; Mulvale et al., Reference Mulvale, Embrett and Razavi2016). Individual interprofessional collaboration teams have opportunities to improve collaboration regardless of the organisational or policy context within which they operate. So successful integrated care (ie, models that are effective in meeting patient needs) demands (interprofessional) collaboration and the ongoing involvement of patients and family carers in programme planning, implementation and oversight. This will ensure that user needs and expectations are reflected when it counts, and that consumer satisfaction issues can be realistically addressed (Kodner and Spreeuwenberg, Reference Kodner and Spreeuwenberg2002).

Figure 1 Model of interprofessional collaboration and difference with multi-professional collaboration (based on McGill, 2001; Yaffe et al., Reference Yaffe, Dulka and Kosberg2001)

Little is known about how interprofessional healthcare providers in nursing homes work together (Nazir et al., Reference Nazir, Unroe, Tegeler, Khan, Azar and Boustani2013; Tsakitzidis et al., Reference Tsakitzidis, Timmermans, Callewaert, Verhoeven, Lopez-Hartman, Truijen and Van Royen2016). From the literature it is noticed that the existing collaboration within usual care in nursing homes is rarely described. This makes it difficult to fully understand what makes the interprofessional collaboration as intervention effective, in comparison with the usual care (Tsakitzidis et al., Reference Tsakitzidis, Timmermans, Callewaert, Verhoeven, Lopez-Hartman, Truijen and Van Royen2016). We know that interprofessional teamwork evolves from trial and error learning (McCallin, Reference McCallin2004) and so interprofessional collaboration has to be actively taught (Barr, Reference Barr2002; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2005).

There is also limited insight in the perceptions and the factors that have an impact on (or barriers and enablers of) collaboration in nursing homes (Nazir et al., Reference Nazir, Unroe, Tegeler, Khan, Azar and Boustani2013).To make a success of integrated care, formal structures may need to be put in place for health service delivery and organisation of care for care homes (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Goodman, Bunn, Victor, Dickinson, Iliffe and Froggatt2011). Barriers to integrated collaboration include a failure to acknowledge the expertise of care home staff, their lack of access to healthcare services, as well as high care home staff turnover and limited availability of training. The care home manager supports the process of integrated care through facilitating trainings for all levels of care home staff professionals (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Goodman, Bunn, Victor, Dickinson, Iliffe and Froggatt2011). When different health professionals promote or recognise a common social identity, built on shared views and goals, integrated care can be facilitated (Amador et al., Reference Amador, Goodman, Mathie and Nicholson2016). Further insight is needed in how interprofessional collaboration in nursing homes is understood and experienced. This will support the education of future healthcare providers regarding their responsibilities in multidisciplinary teams in order to work interprofessionally to deliver the required care within their context.

Aim

This study aims to gain insights in the perception of professionals towards interprofessional collaboration in nursing homes and the factors that have an impact on interprofessional collaboration.

Design

Based on the research question to investigate how interprofessional collaboration in nursing homes is understood and experienced, the study used a qualitative descriptive methodology (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). Focus group interviews and additional semi-structured interviews were performed. The focus group interviews were used to elicit the multiplicity of perceived roles within a group context, gaining a larger amount of information in a shorter period of time (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs1997). The semi-structured interviews further explored individual attitudes, beliefs and feelings and went more in depth with the preliminary findings from the focus groups (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs1997).

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Antwerp (number: UA A11-01). Participants were all informed about the process, and confidentiality was respected for all gathered information.

Data collection and participants

The National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (NIHDI) provided us with of a list of officially recognised existing nursing homes in the province of Antwerp. All eligible nursing homes (n=194) received a written invitation to participate in this qualitative research. The Belgian model (the also including the province of Antwerp) of long-term residential care for the elderly is rather unique. Homes for the elderly and nursing/care homes offer a home-replacing environment when possibilities for long-term care at home or short-term residential care are no longer sufficient, after (re)-assessment of the severity of ADL or instrumental ADL limitations. In 2007 there were about 566.000 persons with moderate to severe levels of dependence in Belgium (on a total population of 10.6 million and a 1.8 million population aged 65+), a number which will double by 2060 (Willemé, 2010). About 123,000 (22% of disabled elderly or 7% of the 65+ population) mainly elderly persons are living in homes for the elderly (73,000) and nursing homes (50,000). There is a mix of residents with mild and severe disability, and also older people with dementia living together in one institution. The elderly can move between different levels of care, from a home for the elderly to a nursing home, without leaving the institution. All institutions are well spread over the country (Stichele et al., 2006). About 39,000 fulltime-equivalent nurses are taking care of elderly in homes for the elderly and nursing homes. General practitioners (GPs) have responsibility for the clinical care of the elderly in these institutions. Also other primary healthcare services are involved in the medical care. The health insurance system covers nursing care (as well as paramedical and rehabilitations care) for dependent persons. Non-medical expenses are not covered, leaving a big financial burden to the elderly – with a nursing home bill of more than € 1600/month – which is higher than the average pension of € 1300/month. This burden is partly alleviated by some other cash benefits such as the allowance for assistance to elderly persons.

After a period of three weeks every nursing home was called to ask if they received the invitation and if they had personnel interested to participate in a focus group. The coordinator of the nursing home proposed a list of participants. Finally the purposive sample consisted of professionals from nursing homes (profit and non-profit) representing different geographical areas within the province of Antwerp. Recruitment was not easy, a lot of nursing homes and/or personnel rejected to participate even after showing initial interest and confirmation to participate. Eventually three focus groups were conducted and took place at the University of Antwerp during working hours and lasted ~2 h. Focus groups were ‘mono-disciplinary’ to better understand the perception of the roles in interprofessional collaboration within a specific group of healthcare professionals, as well as to avoid bias in responding because of hierarchic relations. The first focus group was held with GPs, the second one with nurses and the third one with paramedic disciplines of physiotherapists (PT) and occupational therapists (OTs) (see Table 1). The focus groups were facilitated by a moderator (L.S., a psychologist) using an interview guide to lead the discussion, and observed by a member of the research team (G.T., a physiotherapist) who took field notes during the sessions. The interview guide was developed by the research team (P.V.R., H.M., S.T. and G.T.) and reviewed by colleagues for comprehensibility and feasibility. The interview guide for the focus groups started with an introductory question to get acquainted with each other. Then several open questions followed; the first explored the description of the global organisation of their nursing home and how they perceived their own role in collaboration. This was followed by two open questions about how the care was being organised and what the future aim was of the nursing home regarding the care. Each focus group was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Additional individual interviews (see Table 1) were executed with professionals from the representative specific healthcare professionals semi-structured interviews were face-to-face with the participant and the interviewer (G.T.). These interviews lasted ~1 h, were recorded and transcribed ad verbatim.

Table 1 Description of characteristics participants – health professionals

GP=general practitioner; GP CPN=general practitioner as coordinating physician in a nursing home; GP OOH=GP out of hours; PT=physiotherapist; HPT=head physiotherapy; OT=occupational therapist; N=nurse; HN=head nurse; NA=nurse auxiliary; MB=management board; HPaT=head paramedic team; P=paramedics.

Analysis

A thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was performed. A group of four researchers from different disciplines(a psychologist, a sociologist, an occupational therapist and a physiotherapist (L.S., S.A., N.C. and G.L.)) read one focus group and four interviews to immerse in the data and initial ideas were noted by the team. This phase produced the initial codes from the data. Both open coding (identification of primary themes) and axial coding (analysis of relationships among themes) were conducted (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) and re-focussed into potential themes. Subsequently, three out of the five initial analysts (N.C., G.L. and G.T.) revised and refined emergent themes through constant comparison of instances from the data set. They compared interpretive memos and discussed relationships between categories. Discrepancies were given particular attention to ensure the validity of the analysis: they were considered by consulting specific instances in the transcripts, discussing their relationship to established themes and reaching consensus as a group (Creshwell, Reference Creshwell2003).

Findings

Participants

In total three focus group sessions were held: one focus group with GPs (n=6), one with nurses (n=4) and one focus group with paramedic disciplines including three PTs and one OT (n=4). In addition, nine semi-structured interviews were executed, with a coordinating GP (Coordinating physician in a nursing home), a head nurse, a nurse, two nursing auxiliaries, two GPs from out-of-hours services, one physiotherapist and one member of a nursing home management board. One GP who took part in the focus group gave an additional individual interview on her experience of out-of-hours practice.

Four main themes represented the perception and factors that impact interprofessional collaboration: context, collaboration, care, and experience. These themes emerged consistently from all focus groups and interviews. Even though usual care was described differently, all participants expressed a tension between the ways they would like to collaborate and the way collaboration is being experienced in daily practice.

‘Context’ of working is more professional-centred than patient-centred

In this theme, the context is described from the experiences of professionals that can influence collaboration. In nursing homes mainly GPs, nurses, physiotherapists and nursing auxiliaries are involved in the care for residents.

GPs, who work independently in private (often solo) practice, consciously choose to continue (or not) seeing their patient when they move to a nursing home and have between two and 18 patients living in a nursing home. The decision whether to continue visiting the patient is based on the distance from a nursing home relative to their practice, and whether it is located on their work path. Occasionally GPs make an exception based upon their relationship with the patient. This raises the question if continuity of the care of the residents depends upon the willingness and practical considerations of their GPs?

‘…Normally we do the follow-up of our patients if they go to a nursing home nearby, but if it’s too far away, we do not do that” (FG (Focus group) – GPX p2 line 42) “…within 5 km of the practice more or less”’.

(FG GPY, p. 2, line 49)

‘One of them is now in a nursing home in a village further away, she is actually a chronic patient who I have actually known from years back when she was still living at home and I have continued to visit her because otherwise she had to change GP and I didn’t want her to go through that’.

(FG – GPZ, p. 2, line 61)

As regards to physiotherapy on the whole, there are two to five physiotherapists available in nursing homes. Physiotherapists work on prescription and therefore the number of patients in treatment also depends on the situation of the residents in the nursing homes. This means that not all physiotherapist work fulltime and that they are as a discipline less involved in planning the care.

Nurses and nursing auxiliary’s work in shifts and, depending on the size of the nursing home, they are mostly responsible of ~30 residents. A head nurse leads the ‘care-team’. Head nurses work as managers but often they are also involved in the actual care in order to feel more engaged with the care for their residents. It stays unclear whether the head nurses take responsibility for the ‘teamwork’ and if they bring the information and disciplines together.

‘… I am no longer doing patient care, as a head nurse I truly do the work of a head nurse I think then, in the sense that I do not have to wash residents, nor do I have to make their beds, I don’t give medicine…’.

(FG – N, p. 9, line 306)

‘…I am helping a little bit here and there when necessary, and at eight o’clock I try to organize and give the medication, that’s pretty much my job, euhm why I do this well … because it actually gives me the opportunity to see all residents…’.

(Interview – HN, p. 6, line 175)

Even members of the nursing home management board try to keep in close contact with the residents by participating actively in the workplace.

‘…So I hope with being there more, and I already see results that is an observation that previously came from the nursing auxiliaries and nurse team, that animators were never seen in the department, which was also true…’

(I – HPaT, p. 8, line 276)

‘No collaboration’ or ‘Collaboration’ limited to information exchange

Collaboration is mainly described as helping each other independently of being a professional, a resident, family or volunteer. Unfortunately in nursing homes collaboration is expressed in tasks that professionals perform to offer the best care possible for residents and to get the prescribed performance supplied. Collaboration is mainly limited to information exchange throughout different communication channels, for example, consultations, mono- and multi-professional briefings. Within the nursing homes paramedics work in ‘separate’ groups. First, there is the team of nurses and nursing auxiliary for the care. Second, there are all other professions such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, etc., often named the ‘paramedics team’.

‘…us physios have taken matters into our own hands, so basically we are self- employed physiotherapists so we do our work under the lead of the head nurse so basically the head nurse is our boss but actually we decide ourselves how our work has to be done. I mean we plan our work we have been working with two physiotherapists who are self-employed for many years. We simply organize our work ourselves because we as physiotherapist have the best insight on what you can offer as a physiotherapist or do in given situation; while the nurses, they often have a slightly different view’.

(FG – PT, p. 4, line 128)

In a lot of nursing homes it is noted that staff wear a uniform without an explicit difference between disciplines. As GPs indicate a head nurse as the most important contact person, it would be easy recognising them because of their uniform. Implicitly this confirms that GPs do not really know or recognise staff of the nursing homes.

‘S. They know a lot about their patients, so I hope it is the head nurse … she can also be a nurse, anyway it will be a nurse’.

(I – GP – OOH 1, p. 9, line 284)

Nurses confirm that GPs depend on them for important information but they also complain about collaboration with GPs. Some GPs promise to make a visit for acute situations but often they do not turn up or visit on another day. This can affect the support or feedback GPs receive because there is not always a nurse available depending on the time they arrive in the nursing home.

‘…problem is also that with us, there are a lot of GPs who come in the afternoon, that is to say that there are two nursing auxiliaries at that moment who know nothing of the program nor about the medication or about the care record and if so they cannot actually help the GP…’.

(FG – N, p. 34, line 1143)

During the weekend it seems that communication and information exchange is organised differently. Doctors from out-of-hours practice declare that they do not always know the professional profile of the person who gives them the information. Therefore, GPs are unsure about the quality of the information they receive. This results in the possibility of lacking important information in certain situations and can compromise continuity of care.

‘S. it is sometimes creepy, because you only read “shortness of breath” as a doctor. If you then for example receive a phone call, that at least you can ask a little bit more “ah yes breathlessness and there are other complaints?’, but so euhm during out of hours you get only “shortness of breath” on a little paper…’.

(I – GP, OOH 1, p. 4, line 114)

In nursing homes multi-professional consultations are regularly organised. Unfortunately not all disciplines are always represented. It seems difficult to find appropriate moments for everybody involved per case. The content of the consultations is mainly about the residents’ evolution or problems to be solved, especially when there is a decline of the residents’ health situation. So no proactive planning of the care is mentioned. Generally the tasks and collaboration between professionals are performed as they present themselves ad hoc. According to the GPs the ‘better nursing homes’ are those where it is clear what the tasks are for each discipline then a more structured collaboration is present. According to the GPs these aspects facilitate collaboration in order to achieve the goals of the care plans.

‘…There are some nursing homes, where indeed, occasionally everything goes completely wrong. There are some nursing homes where everything goes very well, where the organisation is better. And you have some nursing homes where sometimes they know you will normally be there the next day and they still pretend that you have to come urgently the day before. When you get there, it often seems that you could have waited until the next day’.

(FG – GP, p. 4, line 141)

The ‘care’ is described as routine tasks to be done

This theme is described in terms of how and which care is organised, and how continuity of care is pursued. All the ‘actions’ take place in the morning to get the care done. All professionals in the nursing homes are busy to get all residents washed and dressed. A lot of therapies are also planned in the morning. There is little time for a chat with the residents. GPs that are not immediately linked to the nursing homes come and go as it suits them personally. Nurses ensure that doctors prescribe what they think residents need.

‘I get prescriptions for residents and these are listed on a big board so that I know which patients I have to give therapy to and on which day, so I’ll see which patients I have to do today and euhhm then I already start than I know oops that resident was sick so I must not treat him today, and then I can start with my work, so I’m going eum looking for the first resident to treat’.

(FG – PT and OT, p. 3, line 83)

The tasks are fairly routinely organised, fixed times for breakfast, lunch, afternoon snack, drink tour, etc. Follow-up of care is mainly done through briefings, multidisciplinary consultation and not by integrated care planning. During the weekends and during holiday periods the basic care continues but, the workforce is much smaller. Planning revolves around tasks to be done.

It seems that no time is taken to plan the ‘care’ and to ‘take care’ of the residents, which demonstrates that there is no coordination of care to create an integrated care plan. Everyone has the best intentions and works with best endeavours to offer the highest quality possible, but, time and time pressure throw a spanner in the works. Professional health workers admit that therefore residents do not receive the ‘care’ they deserve.

‘Sometimes it contains a bit of the danger of the routine could be, that you say as of now I’m going in there and I do that and that and that and surely as the pressure is there. I am already with my thoughts on the next thing, in oh I have to go there and then I have this and that to be done, and that I also should not forget these things but meanwhile I am with a resident engaged and I am with my mind already with another resident because I have to organise everything. I try to get everything scheduled, and that should not be the things in my mind when I am with a resident but yes I do so, and that has to do with the pressure, I think’.

(FG – N, p. 40, line 1337)

‘Experience’ about collaboration

The experiences GPs have with collaboration and communication with nursing homes are very diverse. Sometimes GPs get the feeling there is no internal communication in nursing homes. They receive on unexpected moments requests for an urgent visit, but once they get there it seems a pure administrative question. GPs get dispirited to comment on requests for visits. GPs indicate that staff involvement with the residents and enthusiasm of staff is the most important indicator to label a nursing home as a ‘good’ nursing home.

‘M.…when you see that residents are happy, I wonder if they are satisfied with the care, and I think that often these are the nursing homes where better and more staff is present when the residents are happy…’.

(FG – GP, p. 32, line 1034)

Nurses complain about having little time to talk or chat with the residents. They do not have time to ‘take care’ of the people in a personalised way. On the other hand, nursing auxiliaries expressed their experience as being satisfied with their work and also have time to be there for their residents. This confirms that a personal approach with residents seems important.

‘S. Yes because actually I don’t like hearing “what do I do now”, there is always something to do, you must not work eight hours or six hours or four hours in a row, I think it’s important to sit down once in a while, have something to drink, have a chat with your colleagues about your private life, but that you can see what work needs to be done and that it is done which I find very important’.

(I – NA 1, p. 17, line 517)

Physiotherapists complain about the communication between professionals. They depend on written information to exchange thoughts, concerns and just the status of the residents. They are not involved in the briefings of the nurses and nursing auxiliaries and thus no integrated care planning is present. They are concerned about giving quality treatments because of the lack of information.

‘…but to us it remains still a tricky issue that the care givers themselves are very difficult to motivate to read something or to communicate the received care in the right way, you have already repeated the issue and one month later you have to repeat what you have in fact told them already a month ago, and is already like this and nothings has changed in over twelve years, it’s terrible…’.

(FG – PT, p. 7, line 241)

Discussion

The aim of this study is to gain insights in the perception of healthcare professionals towards interprofessional collaboration in nursing homes and the factors that impact the interprofessional collaboration. Four main themes emerge from the analysis: context, collaboration, care and experience. The themes gave us valuable information about how interprofessional collaboration is performed in practice. As in the definition, interprofessional collaboration involves the awareness of different roles in the team (Vinicor, Reference Vinicor1995; Leathard, Reference Leathard2003; D’Amour et al., Reference Dagneaux, Gilard and De Lepeleire2005; WHO, 2010; Tsakitzidis and Van Royen, Reference Tsakitzidis and Van Royen2015). No additional energy is invested in identifying personnel or staff. In relation to discipline identification as described by the participants, care providers do not know the competences associated with the discipline, even though professional identity is important before interprofessional relationships can be successful (Molyneux, Reference Molyneux2001). Sometimes the only visible difference of disciplines can be noticed through the different uniforms.

In interprofessional collaboration there is a model of working together between different healthcare providers (Leathard, Reference Leathard2003). All disciplines/professionals really try to inform each other with the most current information. because of the way the care is organised it is difficult to even achieve basic needs (a walk, wanting a chat, etc.) of residents. The findings show us that it seems not feasible to expect physicians or other health professionals to perform vital organisational roles in addition to their clinical responsibilities (Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Meuser, Rogers, Lawrie and Reeves2010). Formal team-based care, presence of communication and coordination among team members, and leadership are consistent features of successful interventions for interprofessional care (Nazir et al., Reference Nazir, Unroe, Tegeler, Khan, Azar and Boustani2013). However we found little valid structure in the results of this study in nursing homes. Without an interprofessional collaboration it will be difficult to develop a multidisciplinary integrated and cohesive answer to the needs of the care receivers and their context. The different healthcare professionals in the nursing homes are seen as separate groups. There is little evidence that they are working towards the same goals. There is a first group called ‘care-team’, involving nurses and nursing auxiliaries, the second group involves all paramedics and other non-medical staff working in the nursing home and in the third group there are the GPs. The care as task described by the participants does not reflect the challenges or benefits of interprofessional working.

The shift in responsibility for health and elderly care from acute inpatient settings to the community sector and to family and care providers means that older people and their families should be involved in planning and decisions about their care and identifying what would be of most assistance to them (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hutchinson, Brown and Livingston2014). From our data the participants see these care tasks still as their core business and they do not immediately link their task to other healthcare professionals or families and do not immediately look for ways to work in a more interprofessional way. Seemingly everyone wants to do everything at once, but there is no one taking responsibility for making the ‘groups’ work as a team. Collaboration between different disciplines in nursing homes presented itself as fragmentary. The interprofessional relationship between GPs and nurses is described as an important factor for collaboration. In every nursing home nurses are seen as the most important contact person. But for nurses it is difficult to work with so many GPs who all work differently. And with staff shortage a lot of nursing auxiliaries help out the nurses. On the other hand, knowing GPs have different patients in different nursing homes, good structure could help not to lose time looking for the right professional to receive relevant information. From the perspective of the GPs, collaboration is influenced by the fact that they always have to adjust their way of working and that there are often problems with accessibility of the nursing home. During the weekend GPs often describe the care different from that during the week. The transfer of information is often very concise and can therefore not be labelled as ‘good’. Sometimes it even creates an unsafe feeling for GPs. Physicians have more legal accountability for medical decisions, so they have to receive as much information as possible. In a study among GPs in Germany, it was shown that GPs apply different strategies to achieve a productive performance when visiting a patient in a nursing home (Fleischmann et al., Reference Fleischmann, Tetzlaff, Werle, Geister, Scherer, Weyerer, Hummers-Pradier and Mueller2016). In Belgian study it is shown that collaboration between GPs and geriatricians is enhanced by exchanging information on, and reflections on roles and competencies (Dagneaux et al., Reference D’Amour, Ferrada-Videla, San Martin Rodriguez and Beaulieu2012). Therefore by openly recognising and discussing the tensions between traditional and interprofessional discourses of collaborative leadership, it may be possible to help interprofessional teams, physicians and clinicians alike, to work together more effectively (Lingard et al., Reference Lingard, Vanstone, Durrant, Fleming-Carroll, Lowe, Rashotte, Sinclair and Tallett2012). In usual care a lot of collaboration is perceived, but in our results no common vision or responsibility sharing is found. The role description of the different disciplines does not always seem clear nor is it always explicit. It is a matter of getting the task done.

Globally the results illustrate that in nursing homes it is not only about ‘taking care of’ but it is all about ‘caring for’. Nursing auxiliaries explicitly mentioned they make time for their residents and have consciously chosen to ensure an enjoyable stay in broader terms than just provision of basic care. They sense that being there for the residents is the most important task. Every professional wants to do well for the residents and provide qualitative care. Therefore knowing and understanding the definition of interprofessional collaboration in healthcare is important. Next to what the definition involves for interprofessional collaboration, the indication that the involvement of the staff plays an important role should also be taken into account. When we look at it in a more general way (transferability of the data) ‘care’ is perhaps not only a matter of time management and taking the right medication at the right time. Healthcare professionals still need to reflect on, and reconsider their attitudes, approaches and expectations towards both traditional ways of working and professional power balances in interprofessional settings (Molyneux, Reference Molyneux2001; Nazir et al., Reference Nazir, Unroe, Tegeler, Khan, Azar and Boustani2013). Within healthcare teams, formal and social processes and team structure are critical considerations. There is need for a paradigm shift from single-profession healthcare delivery toward integrated care in which several disciplines work together in interprofessional teams to address an individual’s needs (Vinicor, Reference Vinicor1995; Leathard, Reference Leathard2003; D’Amour et al., Reference Dagneaux, Gilard and De Lepeleire2005).

Many straightforward actions can be taken at this level, such as dedicating human resources to championing collaboration, setting a common vision and goals, attending to formal and social processes to minimise conflict and value the contributions of team members. Ongoing reflection for continuous improvement of the full team is required, through formal mechanisms like quality audits, as well as regularly scheduled team meetings. At the same time, the context within which the team operates is important, although understudied (Mulvale et al., Reference Mulvale, Embrett and Razavi2016). So what is the goal of the care plan and which role do the different disciplines play to achieve the goal with a ‘common vision’ and ‘shared responsibility’? Who will lead the team to provide the best patient-centred care possible? How will we grow to a more interprofessional working model such as integrated care (Kodner and Spreeuwenberg, Reference Kodner and Spreeuwenberg2002). With this study we confirm that patient’s problems are subdivided and treated separately (Page, Reference Page2009) and so healthcare professionals do not work interprofessionally according to definitions from the literature. More research in primary care is needed with the aim to get better insight in the process of changing from an existing working model to a more interprofessional working model.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our results are based on the findings of a particular setting and their relevance in other settings needs to be further explored. However data triangulation with use of focus group and additional individual interviews using different perspectives in data analysis allowed us to explore the perceptions and experiences with interprofessional collaboration. However perceptions and experiences have their limitations and are only one component of the description of collaboration in usual care. In addition to our study it would be good to gain more insight in how the care is actually delivered. Other methodologies can be used such as (non)participant observation or questionnaires or even a quantitative study.

Conclusion

This study provides insight in the perception of healthcare professionals towards interprofessional collaboration in nursing homes. In usual care the perceived interactions between professionals is called collaboration. Obviously physicians and all healthcare professionals do not work interprofessionally according to definitions from the literature. This study provided evidence of the awareness that interprofessional collaboration in usual care is situational and fragmentary organised. From the results and form the literature it seems that healthcare professionals need more training to advance their knowledge about how to collaborate interprofessionally. It is more than just the sum of tasks divided over different disciplines, attention for formal and social processes is needed. Research on implementation of interprofessional education in practice and its effect is needed to get insight on how to create a more common vision on taking care in order to deliver more integrated and so patient-centred care.