Melismas are sometimes used in medieval liturgical music as optional embellishments for official chants. Notable among these are the melodiae for use with the Alleluia, the melismas sometimes used to decorate the repetenda of a responsory in the Divine Office, the great melismatic creations for the Kyrie eleison, and occasional additions to other elements of the Ordinary, such as the Gloria in excelsis and the Osanna. All these have been noted and studied by scholars and have much to teach us.Footnote 1

My subject, here, is a narrower one: the melismas used to embellish the performance of the introit in manuscripts of Aquitanian origin. Up until now, these have not been subject to extensive scholarly scrutiny and deserve our notice. Such melismas are evident when they are indicated, as they sometimes are in other contexts, by labels or rubrics. Equally often, as here, they stand out as variants of a widely attested tradition. It is easy to notice a lengthy melisma added to the end of a standardised verse-formula, especially when it is the second verse, Gloria patri, added to an introit.

Melismas are particularly difficult to categorise, catalogue and edit, since, by definition, they consist of a single syllable. When a melisma is added to a chant, it does not change the chant's words, and so it may escape notice in editions that concern themselves only with text.

The addition of poetical words to official chants – the phenomenon known as troping – is well known and has been studied for a long time. It is to Michel Huglo that we owe the first serious notice of melismas used as tropes – that is, as wordless additions to official chants. Huglo noted the phenomenon in East Frankish manuscripts and also in those of Aquitaine.Footnote 2 This article is an homage to and an amplification of Huglo's pioneering work. His study, proposing ‘melogene’ and ‘meloform’ tropes (i.e., embellishments derived by adding words to melodies and embellishments arising from newly created words), notes the introit embellishments in both East Frankish and Aquitanian manuscripts. My purpose, here, is to bring Huglo's observations up to date. An initial survey of East Frankish manuscripts, before turning to Aquitanian examples, will essentially cover all the melodic embellishments used for introits in the earlier Middle Ages. I prefer not to use the term ‘trope’ for melodic embellishments, since the term is never so used, to my knowledge, in the sources. Instead, such additions are called neuma or melodia or sequentia – if, indeed, they are labelled anything at all.

Before turning to Aquitaine, I present a summary of the situation in the East Frankish manuscripts. Two early manuscripts of St Gall (the troper, St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, 484 and the versicularium-troper-sequentiary, St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, 381), written by the same scribe in the second and third quarters of the tenth century, have melismas of moderate length as additions to the introit of the Mass for major feasts.Footnote 3 Such melismas appear only in tropers before the year 1000 and are evidently in the course of disappearance in some of those.Footnote 4

In St Gall 484 and 391, sets of melismas are provided for introits of major feasts: these are cued to be placed after successive phrases of the introit, the verse, the Gloria and the versus ad repetendum. Some introits, notably those for Easter, are provided with several such sets. These melismas are mostly of modest length, some ten to thirty notes, and do not appear to contain any reduplications within their melodies. There are more than 650 such melismas connected with some thirty introits; introits for principal feasts usually have several sets. More than 100 of the melismas appear more than once. About 200 of them appear in conjunction with texts that are fitted to the music in the manner of a prosula.Footnote 5 The collection is actually quite extensive in manuscripts associated with St Gall, extending to feasts of secondary importance, including the octaves of Easter and Pentecost.Footnote 6

Aquitaine

The Aquitanian style of melismatic additions for introits consists of two elements. The first phenomenon is similar to that of the East Frankish melismatic tropes, but used much more rarely, and for major feasts only: the addition of melismas to the ends of several phrases of the choral portion of the introit, but not, in these sources, to the psalmody. The second style consists of the addition of melismas to the doxology, perhaps to be used on major feasts. Some of these melismas are attached to specific introits; others, found in tonaries, are perhaps intended to apply to any introit of the indicated mode. Such melismas, the last soloistic sound of the introit, would provide a final flourish and a signal to begin the final repetition of the introit antiphon.

The manuscripts considered (and not considered) in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Aquitanian graduals, tropers, tonaries considered here

a Michel Huglo, Les tonaires. Inventaire, Analyse, Comparaison (Paris, 1971) describes the manuscripts on pp. 129–65. See also Heinrich Husmann, Tropen- und Sequenzenhandschriften, RISM Bv1 (Munich, 1964); David Hughes, ‘Further Notes on the Grouping of the Aquitanian Tropers’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 19 (1966), 3–12; James Grier, Ademarus cabennensis monachus et musicus, Corpus Christianorum, Autographa Medii Aevi 7 (Turnhout, 2018), 22–61.

Manuscripts with tonaries not taken into consideration: BnF lat. 7185, fols. 117–125v, fragment s12 (Huglo, Tonaires, 150–4); BnF lat. 7211 (Huglo, 156–7), fragments of four tonaries; BnF n.a.l. 443 (Huglo, 158–9); Naples, BN VII D 14 (Huglo, 157–9); Barcelona, Arch. Del a Corona de Aragon, Ripoll 74 (Huglo, 160–1); and London, BL add. 30850, Silos antiphoner (Huglo, 161–2).

Introits with added melismas

Four introits are found written out with additional internal melismas in the Aquitanian tonaries. Generally, they do not include melismas for the doxology's concluding Amen. These are the only Aquitanian sources that resemble the style of melodic additions used in East Frankish manuscripts, but their melismas are not those used for these introits in those manuscripts.

1. Resurrexi, for Easter

This appears with as many as five additional melismas in the Aquitanian graduals and tropers. The arrangements in these manuscripts are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Melismas added to Int. Resurrexi in Aquitanian tropers and tonaries

Key:

A. BnF lat. 1871, fol. 14v

B. BnF lat. 1118, fol. 41

C. BnF lat. 1240, fol. 30–30v, added in lower margin

D. BnF lat. 776, fol. 155

E. BnF lat. 179, fol. 126v

F. BnF lat. 1084, fol. 108

G. BnF lat. 1118, fol. 108

H. BL Harley 4951, fol. 299v

In five tonaries, cues to portions of the introit followed by melismas are found among the pieces in mode 4. The melismas are mostly the same in each case, but their number varies. In three tropers (Paris, BnF lat. 1118, n.a.l. 1871 and lat. 1240), textual additions, or trope-elements, are included in the mixture of introit and melismas (Figure 1). The four shared trope-elements have a notation that makes clear that the additions are not textings of the melismas (lat. 1118 precedes the introit with Gaudete et letamini; lat. 1240 appends an introduction normally used for the Gloria in excelsis).Footnote 7 One of these sources, BnF n.a.l. 1871, adds a melisma for the Amen of the doxology, which is shown as Melisma 4B in Table 4. But it will become clear from the discussion of melismas for the Amen that this is a separate phenomenon. The melody used for the Amen in 1871 is found for this introit (with no tropes or added melismas) also in BnF lat. 779, lat. 780 and lat. 903. Other melismas are used for the Amen with this introit in London, BL Harley 4951 and BnF lat. 776 and lat. 779, as can be seen in the following discussion and in Table 6.

Figure 1. Paris, BnF lat. 1118, fol. 108. Added melismas in the tonary for the introit Resurrexi. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

2. Nunc scio vere for St Peter

Three tonaries give versions of this introit with additional melismas at the ends of phrases. In the section on third-mode introit psalmody, the tonary of BnF lat. 776 (fol. 152v) writes out the introit with melismas added as follows (Figure 2):

Nunc scio vere* quia misit dominus angelum su-* -um et eripuit me [de manu] Herodis* [et de omni] expectacione* ple* bis Iudeo*- rum.

Figure 2. BnF lat. 776, fol. 152v. In this tonary, a melody with added melisma for the doxology of the introit is followed by a truncated version of the introit Nunc scio vere with additional melismas indicated in boxes. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

The tonaries of BL Harley 4951 and of BnF lat. 780 provide the same melismas, but omit the last two. These melismas are present in a number of other tropers accompanied by the trope-set Dum beatus Petrus (BnF lat. 887) or by the set Divina beatus Petrus (BnF lat. 909, lat. 1119, lat. 1120 and lat. 1121).Footnote 8 Similar to Resurrexi, the trope-texts have melodies not related to the added melismas (indeed, BnF n.a.l. lat. 1871 presents the trope-set Divina beatus Petrus without the melismas for the introit).

Some of the manuscripts that preserve Nunc scio with tropes (BnF lat. 1119 and 1120) also provide a melisma for the Amen of the doxology. This melisma (labelled as MEL 3B) is also used in BnF lat. 1084 with a different trope-set, and separately in tonaries in graduals for this and other introits, as will be seen in the following discussion. It is plain that the three phenomena – tropes (with added text), internal melismas, Amen-melismas – are independent.

3. De ventre matris meae for St John the Baptist

The tonaries of BnF lat. 780 (fol. 122v) (Figure 3) and BL Harley 4951 (fol. 295) provide three internal melismas. The same introit is presented in somewhat abbreviated form in BnF lat. 1084, fol. 155 (Figure 4). Neither version includes a melisma on Amen.

Figure 3. BnF lat. 780, fol. 122v (within the tonary). Introit De ventre matris meae, with melismas added at the ends of phrases. Note that the melisma on mee is incomplete (compare the version of lat. 1084 in Figure 4). Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

Figure 4. BnF lat. 1084, fol. 155 (within the tonary). Another version of De ventre matris meae; the melody here on acutum appears to be an abbreviated version of the one in lat. 780 (Figure 3), and there is an additional melisma on protexit me. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

4. Puer natus est for the third mass of Christmas

BnF lat. 887, fol. 11 (Figure 5) provides, in the gradual, a series of four melismas added over the course of the melody.

Figure 5. BnF lat. 887, fol. 11; introit Puer natus est with added melismas. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

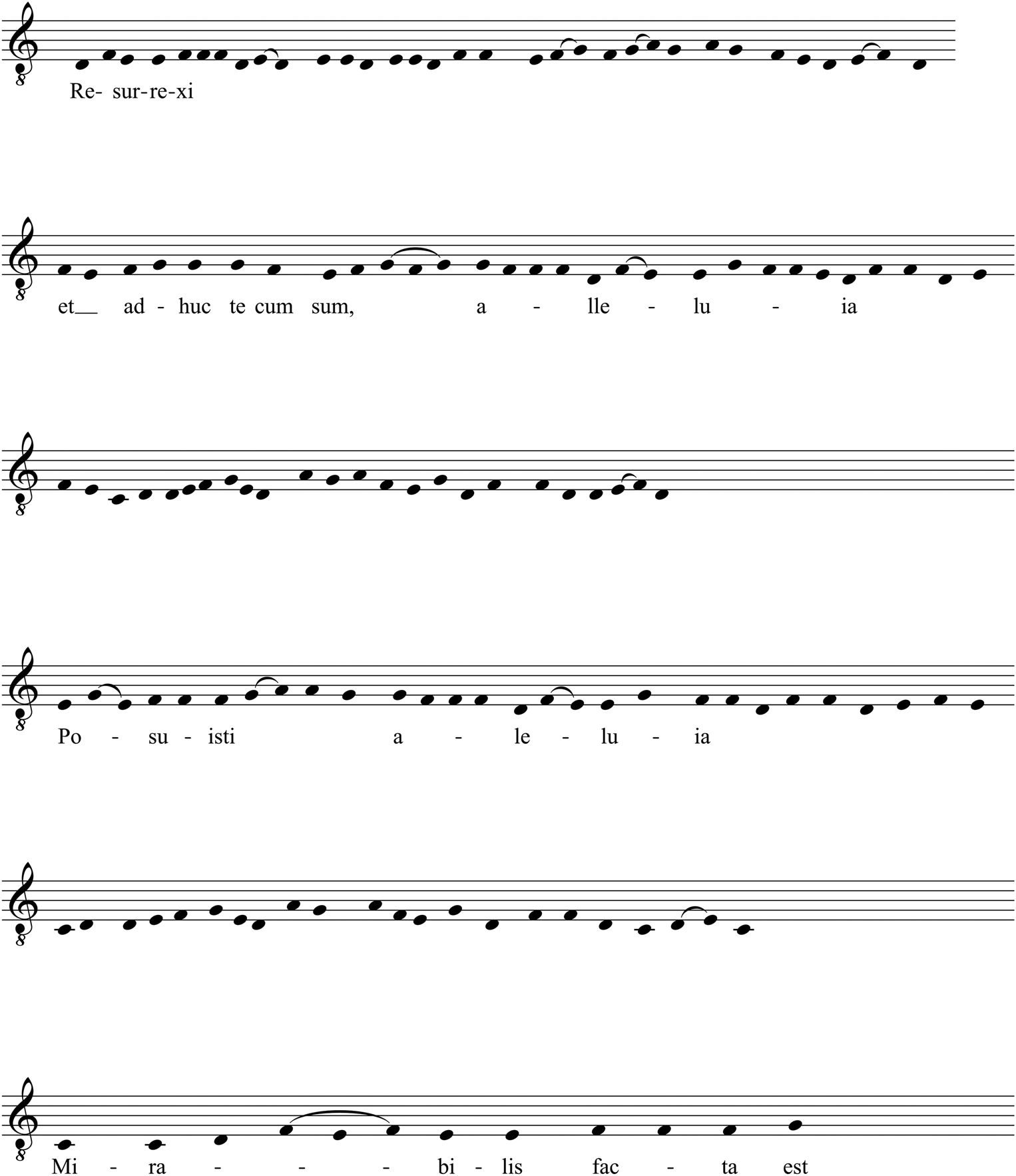

The melodies of all these melismas are relatively clear and make musically suitable extensions of the successive phrases of the introits. One example will perhaps suffice to encourage further analysis. Example 1 provides a transcription of the Introit Resurrexi with its melismas from the tonary of BnF lat. 1118.Footnote 9

Example 1. Resurrexi, from BnF lat. 1118, fol. 108. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF.

The opening melisma begins within the D–F third that limits the introit's first phrases, then rises higher to include the full range of the introit to follow. In a sense this gives away the dynamic of the introit's gradually expanding range. The first melisma ends where it began, so that the second phrase of the introit begins a third higher, just as it would if there had been no melisma.

The second melisma begins on the pitch E, the closing note of the introit's ‘Alleluia’, with a sort of anticipation of the d–f–f of the ‘Alleluia’ that follows the introit's next phrase. Some wide-ranging disjunct motion precedes a close on d, not the e on which the introit would have paused. Then follows the cue ‘Posuisti’, which jumps forward to the ‘alleluia’ leading into the third melisma. This third melisma repeats much of the material from the second, closing on the low C on which pitch the word ‘mirabilis’ continues the introit to its finish.

The melismas occupy mostly the same range, concluding either on d (the first two) or c, leading suitably to the music that follows but, equally suitably, never concluding on the final e of the mode.

Melismas for doxologies

The Gloria patri that normally serves as the second verse of an introit is often given in Aquitanian tonaries as a model for introit psalmody in each mode. In some cases, a decorated version is given in the tonaries, and sometimes a specific melismatic doxology is given with specific introits in the graduals or tropers. It is not always clear in the tonaries whether the melodies are meant to be model melismas for introits in their mode, but comparative study suggests that they are generally separable, moveable and optional.

Melismas in tonaries

Aquitanian tonaries sometimes provide a melisma as one of several possible versions of the doxology, suggesting that the melisma may be applied to any introit in the mode, or any introit in the group whose cues follow in the tonary. There are many versions of doxology psalmody that do not include melismas, so it is not clear from the tonaries whether the melismas themselves are to be considered optional or additional. The same melismas are sometimes found attached to verses or doxologies of specific introits, however, making clear that they are movable additions.Footnote 10 Such a melisma is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. BnF lat. 776, fol. 149v, introit tones, mode 1, differentia 2 (melisma 1B in Table 4). Source: gallica.bnf.fr/BnF. (colour online)

Table 3 lists these melismas from the Aquitanian tonaries. For each mode (there are no melismas for mode 5 or 6), the melismas are indicated according to the differentia (i.e., the numerical order of the versions of introit psalmody; I/2 indicates the second differentia of the first mode). For each mode the melismas are labelled A, B, C or D but of course the melismas are unique to their modes, so that 1A and 2A are different, each the first listed melismas of its respective mode.Footnote 11 Note that most melismas are found in more than one manuscript, that no tonary has more than three melismas for any mode, and that no mode, considered across all the tonaries, has more than four such melismas. No two tonaries have exactly the same collection of melismas.

Table 3. Melismas for introit psalmody in Aquitanian tonaries

It might be suggested that melismas are assigned to the Amen on the basis of the melody of the introit, especially perhaps the introit's beginning, so that the melisma makes a smooth transition from the end of the verse to the reprise of the introit. And to a limited extent this is true, in that tonaries tend to divide the introits of each mode into groups that reflect their melodies, and in particular their beginnings. Thus, the melismas, assigned by differentia, to some extent reflect this. But the matter is not simple or obvious.

Full consideration of this subject is far beyond the scope of this study, but we might take one example to stand for many (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Introits of Mode 1 in the tonary of BnF lat. 780, fol. 122v. (colour online)

The introits (‘officia’) for mode 1 in the tonary of BnF lat. 780, fol. 122v, are arranged in seven differentiae, of which the first and third have Amen-melismas. The following is a summary of the material presented in Figure 7.

DE OFFICIIS Noeoeane

1 Gloria….amen (+melisma)

-

De ventre/Vocavit me/Etenim/Dominus secus/

-

Laudate pueri/Exurge quare

-

2 Seuouaen

-

Rorate/Da pacem/Factus est dominus

-

3 Seuouaen (+melisma)

-

Gaudeamus/Suscepimus

-

4 Seuouaen

-

Exaudi domine vocem/Gaudete

-

5 Seuouaen

-

Sapientiam/Meditatio/Salus autem

-

6 Seuouaen

-

Scio cui/Lex domini

-

7 Seuouaen

-

Misereris

-

Extended melismas are provided for the doxologies of groups 1 and 3. The introits in differentia-groups 1–3 begin low, and those in groups 5–7 begin relatively high (group 4 contains two rather special melodies). This division can explain the various endings of the psalmody given by the tonary, but it does not explain the application of the two melismas (one with group 1 and the other with group 3), which both appear with sets of introits that begin low. Furthermore, the second melisma, with group 3, accompanies two introits that have the characteristic d–a upward leap shared also by the introits in the preceding group.

It is thus not clear here – or elsewhere in the tonaries – whether the melismas have special connections with the introits in their group, and the flexibility demonstrated in the use of these and other melismas makes clear that the assignment of melismas to melodies is a fluid phenomenon.

Melismas in graduals and tropers

These melismas are sometimes found also with individual introits, in graduals and tropers, and in these manuscripts sometimes there are other melismas, not found in any of the tonaries, that are apparently used in the same way. Table 4 is a conspectus of all the melismas used to close introit-verses in Aquitanian manuscripts, indicating which are found in tonaries and which are attached to specific introits in graduals or tropers. This is not a list of all such appearances, but a catalogue selecting one example of each melisma. Further on it will be possible to see all the appearances of each melisma, and which melismas are found with more than one introit. The list in Table 4, compiled from Aquitanian tonaries, graduals and tropers, can serve as a catalogue of all the melismas used in Aquitanian manuscripts for introit-verses.

Table 4. Melodies for introit psalmody in Aquitanian tonaries, tropers and graduals.

a Melismas provided by tonaries, as detailed in Table 2; numbered in column 1 by mode with the addition of upper-case letters.

b Further melismas found with individual introits; labelled in column 1 with lower-case letters; there are also indications of the introit and whether the source manuscript is a troper or a gradual.

A number of graduals and tropers give occasional melismas in association with specific introits. Sometimes these are melismas also shown in one or more of the tonaries, but as noted in Table 4, sometimes they are not. Often a melisma that appears with one introit in one manuscript appears with another elsewhere, and the same introit may bear different melismas in different sources. After considering these collections, we can return to questions of repertory and presentation, such as whether tonaries are accurate summaries of the introit-melismas provided elsewhere in the same manuscript.

The relevant Aquitanian manuscripts, from the late tenth to the early twelfth centuries, vary in their contents: some tonaries appear in manuscripts with graduals, others with tropers, others with both. (Many of these manuscripts also contain prosers and other materials, not considered here.) The manuscripts containing the tonaries we have just mentioned are summarised in Table 1, showing which tonaries accompany graduals and which accompany tropers. (No manuscript gives all three: the only gradual-troper, BnF lat. 903 has no tonary.)

In graduals

Each of the graduals, BnF lat. 776, 780 and 903 and BL Harley 4951, contains a few melismas among the various notations for introit psalmody, generally in association with major feasts. These are indicated in Table 5. (The gradual in BnF lat. 1132 contains no melismas for introits.) Three of the manuscripts, BnF lat. 776 and lat. 780 and BL Harley 4951, also contain tonaries and, to the extent that it can be determined (the tonaries of BnF lat. 776 and Harley 4951 are incomplete), the melodies listed for those manuscripts as coming from tonaries are, indeed, found in their respective tonaries. None of the graduals, however, is limited to melismas found in tonaries, their own manuscript or others: each includes material not provided by any surviving tonary.

Table 5. Melismas for introits in Aquitanian graduals arranged in modal order

a Arranged in modal order; melismas labelled as in Table 4.

These apparently optional or additional melismas are perhaps unusual contents for a gradual; their source is more likely a collection of optional or additional material called a troper. And, indeed, the melismas in tropers are much more numerous than in graduals. After considering the melismas from Aquitanian tropers, we will be in a position to consider the wider distribution of these melismas.

In tropers

Eleven Aquitanian manuscripts contain tropes of the proper of the Mass, and they sometimes include melismas for the Gloria of the introit. Only one of these, BnF lat. 903, also provides a gradual, and we will see that the melismas prescribed in its two sections are not identical. Five of the manuscripts include tonaries, and here we can compare the tonary and troper portions of each manuscript.

The melismas for introit-verses in these manuscripts are tabulated in Table 6, sorted by manuscript in descending size of repertory and, within manuscripts, by mode.

Table 6. Melismas for introits in Aquitanian tropers arranged in modal order

a Arranged in descending order of quantity of melismas for introits, and within each manuscript, arranged modally so as to show the use of added melismas.

bMelismas are labeled as in Table 3:

• ~ similar melisma

• abbr abbreviated

• var variant

Two of the tropers, BnF lat. 903 and lat. 779, have large numbers of Gloria-melismas. Unfortunately, neither has a tonary to which we might refer for comparative study. To judge from other tonaries, about half of their melismas appear also in tonaries. The same is true of the next most abundant source, the Moissac troper BnF n.a.l. 1871 (which, however, presents mostly melismas found elsewhere in tonaries). Perhaps there are two ways of informing cantors about possible melismas: either place them in tonaries where they might be applied to any introit in the mode, or (as in the case of BnF lat. 903, 779 and 1871) place them wherever they should be used, even though this involves repeated writing of the same melisma.

BnF lat. 903 is the only manuscript to contain a gradual and a troper in separate sections (the manuscript does not have a tonary). Its trope section provides a large number of Amen-melismas for specific introits, as seen in Table 6. This manuscript sometimes provides one melisma with the psalm and another with the doxology; they are noted, here, whenever a melisma appears. There are far more melismas for introits in the trope section of BnF lat. 903 than in the gradual section, as might be expected. Of those in the gradual there are three cases (Etenim sederunt; De ventre; Resurrexi) in which the gradual provides a melisma not used at the same place in the troper, three cases (Ex ore, In medio, Spiritus domini) with different melismas for the same introit, and one case in which the two portions agree on a melisma (Puer natus).

No manuscript provides only melismas found also in tonaries, let alone only in a tonary in the same manuscript (capital MEL indicates a melisma found in a tonary, as indicated in Tables 3 and 4).

Ten melismas are found only in tropers – not in tonaries, and not with introits in graduals. Of these, four are used for more than one introit in the same mode, so that there are only six melismas that appear in only one position (and may never have been intended to be movable).

Other tropers have three or fewer melismas, many of them in association with one of the introits with added internal melismas mentioned earlier. It does not seem to matter whether a trope is first or last when there is a series of tropes for an introit; melismas are attached to trope-sets in various positions for a given introit.

Finally, we can consider the entirety of the surviving repertory of melismas for introit-verses. Table 7 combines graduals and tropers, listing all introits that have a melisma attached to verse or doxology. These are sorted by melisma, so that it is easy to see which melismas are widely distributed.

Table 7. Melismas for introits in Aquitanian graduals and tropers

a Arranged to show the use of the various added melismas.

Only for mode 1 do tonaries supply all verse-melismas; for modes 2–8 there are always further melismas used here and there in graduals and tropers. But there is a melisma for mode 2 that is only used in a variant version with introits. Tonaries provide no melismas for mode 6, although there are several in graduals and tropers. There are no melismas anywhere for mode 5. Most manuscripts mix (about half and half) melismas found in tonaries and melismas not found in any tonary. And most melismas appear several times, either distributed among several introits in the same manuscript (cf. mel 1A abbr., used for three introits in 779), or found in several manuscripts (cf. Nunc scio vere and melisma 3B). But there are a few melismas used only once: 2e, 3f, 4c, 4d, 6c, 7f, 8c, 8d and 8 g (six from tropers, three from graduals).

That melismas may be used only once, and that the same introit may have different melismas across different manuscripts (4c and 4d both used for Resurrexi; 8d and 8e both used for Spiritus domini) suggests a value attached to novelty or uniqueness in at least some cases. It may be that such melismas were written down on occasion, either as models in tonaries or as successful moments in graduals and, especially, tropers, but may have been heard far more often from the lips of talented cantors.

* * *

Much more can perhaps be deduced, or imagined, from this information. Of particular interest is the very idea of using a melodic addition to the official chant of the introit. It is true, of course, that tropes are also melodic additions, although they bring their texts with them, but melismas somehow seem different. And, in Aquitaine, at least, they are used in two quite different ways. Rarely, and only for important feasts, a set of melismas is employed at the ends of successive phrases of the introit. These melismas are found most often in tonaries, where they are perhaps meant to be options rather than prescriptions. They are also occasionally written in tropers, where they are found among texted trope-elements, and in collections of tropes for the same introit that make clear that a selection needs to be made from a variety of optional material. These interior melismas for introits make a substantial change in the performative experience of the chant, since they create blocks of words, separated by a lengthy almost-wordless sections. Musically, the melismas remain within the style, range and modality of the introit, but the effect is to pause from time to time for flights of expressive and wordless praise. There is no evidence that these few introits are signs of a larger improvisatory practice; the introits are few, they are the same, and the melismas do not vary.

The other sort of embellishment is quite different. It is a long flourish after, essentially, all the music has been sung: the last syllable of the doxology, on the final Amen, is a moment when a soloist might signal the end of the psalmody and the beginning of the reprise of the introit, with a melodic reflection on the music, the mode, or the spirit of the day. It is too dangerous to posit the ‘meaning’ of such interpolations at a millennium's distance, but the placement, and the idea of spinning out a transitional boundary – of stopping time for a moment – seems likely to occur to anyone. These melismas can be quite long, but rarely do they assume the aabb reduplicative form of many later melismatic additions in other genres.

Makers of manuscripts find various ways of including these melismas, and their choices suggest something about their attitudes and their intentions. It seems clear that tastes, or practices, vary from place to place, since some manuscripts have many of these melismas, and others have few. That difference does not seem to be based on chronology: I can detect no gradual increase, or decrease, over time.

Different types of manuscript deploy these melismas differently. Graduals, which generally tend to include only the official chants of the liturgy, use these melismas quite sparingly. Tropers, the place where exuberant additions are welcome, include many more of them, suggesting that they are among the embellishments available to communities, rather than newly inserted parts of official chants. But the fact that tropers vary widely in the number of such melismas included indicates that tastes, or at least practices, vary. The only manuscript to contain a gradual and a troper together, BnF lat. 903, has very few melismas in the gradual, and a great many in the troper. The presence of many of the same melismas in the tonaries attached to a good number of these manuscripts represents, I think, an attempt to indicate that these melismas are in some sense independent of any particular introit – a fact that cannot be conveyed in a gradual or troper except by writing the same melisma at each place where it might be used. They are, if the tropers are to be believed, part of the equipment that a singer has at his disposition in order to make the liturgy of each day a unique, complete and original offering.