Armed groups in countries as diverse as Algeria, Colombia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Nepal, Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, and Turkey have recruited large numbers of women fighters in recent decades. While some groups use women exclusively for suicide missions or in auxiliary roles, many others employ women combatants in large numbers and even assign them to leadership positions. Most recently, young Kurdish women fighting against the self-styled Islamic State in Syria have had widespread media coverage. The presence of women in armed groups complicates the conventional association between womanhood and victimhood in violent conflicts and indicates a complicated relationship between violent mobilization and female agency (Hill Collins and Bilge Reference Hill Collins and Bilge2016, 130). How does an armed group mobilize a significant number of women fighters? What factors contribute to their decision to join armed groups often at significant risk to their personal safety? What are the distinctive motives of women fighters from different backgrounds?

Informed by an intersectional approach, I suggest that a satisfactory response to the question of why and how so many women with diverse characteristics join an ethnic insurgency requires an explicit focus on interrelated forms of inequalities based on social identities such as ethnicity, gender, and class (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). This approach informs a micro-level empirical strategy and generates several unique insights about both the ability of an ethnic insurgency to mobilize women fighters and the motives of these women.Footnote 1 First, in a context where gender inequality intersects with ethnic inequality, an armed group promising both ethnic and gender emancipation would find a receptive audience among ethnic minority women. Next, the intersection of class and gender among women of an ethnic minority shapes their distinctive patterns of mobilization. An armed group could mobilize women in large numbers when it appeals not only to educated women with a history of political activism, but also to women from more marginalized backgrounds. This is more likely when the group develops a gendered platform that resonates with the life experiences of women whose social roles are defined in terms of fertility and domestic labor. Ultimately, an armed group becomes gender inclusive to the degree it transcends class-based differences among women of its ethnic constituency.

In terms of empirics, I offer an in-depth study of the PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan), an insurgency that has been fighting the Turkish state since 1984. There are three reasons why the case of the PKK offers a unique opportunity to study the core questions of interest. First, the PKK presents a paradigmatic case of women in arms as tens of thousands of women from multiple countries have joined its ranks.Footnote 2 As no other Kurdish militant organization has had the same ability to mobilize such a large number of women, the PKK’s appeal among women cannot be explained by cultural factors unique to Kurdish society. Next, I employ a unique multi-method research design offering more fine-grained empirical analyses than cross-national studies and being particularly suitable for employing an intersectional approach. It builds on an original dataset about PKK fighters (1,385 females and 7,808 males) and utilizes information from extensive fieldwork entailing dozens of in-depth interviews primarily with relatives of these militants, and sources in primary languages. While the dataset identifies general and long-term patterns characterizing women’s mobilization, qualitative research provides information about women’s perceptions and experiences of gender inequality and decision to take arms.Footnote 3 The empirical analysis exploits variation in PKK women recruits’ characteristics and motives to make robust inferences about the effects of gender inequality in shaping the dynamics of women’s participation in the insurgency. Furthermore, it demonstrates how the rise of a PKK gender narrative explains the onset of women’s participation in the insurgent ranks in large numbers.

An important broader implication of this study is that scholarship on armed conflict will be theoretically more innovative and empirically richer if it pays systematic attention to human security dimensions of political violence.Footnote 4 In particular, the study of the causes and dynamics of ethnic violence will benefit from incorporating multiple forms of grievances and discrimination including gender inequality at both the theoretical and empirical levels. Normatively, I suggest that women with multiple marginalized identities could achieve political agency via an unorthodox route unanticipated by liberal feminism: participation in armed rebellion. The paradox is that this agency comes at the expense of women’s own physical security and safety essential for their ability to develop greater capabilities and rights.Footnote 5

Women Joining Armed Groups

Scholars offer a variety of theoretical perspectives to explain the voluntary participation of people in armed rebellions involving huge costs and risks. The perspectives that focus on individual-level cost and benefit calculations suggest state repression (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001; Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Kocher2007; Humphreys and Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008), membership in tightknit communities with strong monitoring and enforcement mechanisms (Hechter Reference Hechter1987), and immediate and future rewards offered by insurgencies (Lichbach Reference Lichbach1994; Weinstein Reference Weinstein2007) motivate participation. The perspectives that focus on social identities, on the other hand, argue that communities with distinctive cultural traits, networks cultivating solidarity, reciprocity and trust that facilitate collective action (Cederman, Wimmer, and Min Reference Cederman, Wimmer and Min2010; Petersen Reference Petersen2001; Parkinson Reference Parkinson2013), moral outrage due to political violence (Wood Reference Wood2003), and political mobilization aggravating collective threat perceptions (Shesterinina Reference Shesterinina2016; Tezcür Reference Tezcür2016) contribute to the decision to rebel.

Some studies specifically focus on gendered dynamics of women’s participation in armed groups in civil wars. Regarding the organizational (demand) factors, armed groups with leftist and gender progressive ideologies and gender-inclusive characteristics are more likely to have both women members and combatants (Reif Reference Reif1986; Wood and Thomas Reference Wood and Thomas2017). In Africa, armed groups pursuing non-secessionist goals and employing forced recruitment and terrorist tactics are more likely to field a higher ratio of women (Thomas and Bond Reference Thomas and Bond2015). Regarding societal factors, three aspects of gender relations influence the dynamics of women’s female recruitment. First, the dismantling of traditional family structures caused by economic transformations and wartime dynamics increase the number of women in informal economy and nonviolent popular organizations. Women who develop political skills and efficacy in these organizations become more likely to join insurgents as state repression targets non-violent mobilization (Mason Reference Mason1992; Kampwirth Reference Kampwirth2003; Wood Reference Wood2008). Next, the practice and fear of sexual abuses and rape by security or paramilitary forces lead women to join insurgents in pursuit of protection and revenge (Alison Reference Alison2003; Bloom Reference Bloom2011).Footnote 6 For instance, the FMLN (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional) in El Salvador effectively developed a recruitment narrative of protection from rape by security forces that aimed to restore the traditional family structure (Viterna Reference Viterna2013, 112-3).Footnote 7

A third aspect concerns the impact of gender inequality on women’s violent mobilization.Footnote 8 According to an influential perspective, women with greater social capital, educational achievements and involvement in broader economic life are more likely to join armed groups in civil wars. These women have valuable skills demanded by insurgent organizations, are embedded in face-to-face social networks conducive to political mobilization, and exhibit higher levels of political awareness and efficacy (Thomas and Wood Reference Thomas and Wood2018).Footnote 9 In contrast, undereducated women lacking social capital, a historical of political activism, and involvement in paid economic activities are more likely to face significantly higher barriers to mobilization (Reif Reference Reif1986). An opposing perspective, however, suggests that rural and lower class women are more likely to be receptive to revolutionary platforms. The opportunity cost of joining an armed group would be lower for these women who have fewer alternative life options than educated and middle-class women. Moreover, revolutionary leaders often specifically aim to mobilize lower-class women whom they portray as victims of multiple forms of exploitation (e.g., ethnic/racial, class, and gender).Footnote 10 They offer a collective action frame constructing a new gendered social identity.Footnote 11 Such a framing becomes most effective when it problematizes practices (i.e., women’s domestic confinement) that are long perceived as normal by women (i.e., providing a cognitive opening) while offering a feasible way to overcome these practices (i.e., joining the nationalist struggle).Footnote 12

I develop intersectional conceptual and methodological lenses to analyze women’s violent mobilization in the face of these contrasting theoretical perspectives.Footnote 13 Espousing an intercategorical approach of intersectionality, I focus on “relationships of inequality among social groups and changing configurations of inequality along multiple and conflicting dimensions (McCall Reference McCall2005, 1773).” More specifically, I highlight three types of unequal relationships: (a) between women of an ethnic majority and minority, (b) between women and men of an ethnic minority, and (c) between ethnic minority women from different class backgrounds. A satisfactory analysis of the success of an insurgency to recruit women and the distinctive motives of these women fighters requires a systematic attention to these three types of structurally generated unequal relationships. For some individuals, their experiences as members of a marginalized minority may be more relevant for their decision to join an insurgency; for others, class plays a more decisive role (Dietrich Ortega 2011). Violent mobilization reflects distinctive experiences of women shaped by their membership in multiple social groupings embedded in specific historical contexts (Weldon Reference Weldon2006, 236; Hancock 2007). Consequently, the impact of a particular form of social identity on mobilization is contingent and exhibits distinctive patterns. From a methodological point of view, this approach deconstructs larger social categories and makes it possible to identify the multiple paths of violent mobilization in a parsimonious manner.Footnote 14

This intersectional approach informs three testable theoretical propositions about the causal dynamics of women’s participation in an armed group. First, women experience gender-based subjugation in diverse ways reflecting their class, racial, and ethnic identities (Yuval-Davis Reference Yuval-Davis1997, 7; 2011, 16; Hancock 2007). It is important to distinguish between contexts where gender inequality intersects with regional, racial, or ethnic inequalities that are the center of political conflict and contexts where gender inequalities do not exhibit similar patterns such as the Basque Country in Spain.Footnote 15 An insurgent group promising gender emancipation via revolutionary struggle is likely to have more appeal in the eyes of women in contexts with intersecting inequalities such as Kurdish regions of Turkey. Consequently, the emergence of a gender-progressive platform specifically addressing women’s issues by an armed group will significantly contribute to its ability to mobilize women in large numbers in a context where gender inequality intersects with ethnic and class identities to generate interlocked forms of marginalization and inequality.

Next, it is important to distinguish between insurgencies that typically operate in urban communities (e.g., Tupamaros in Uruguay, IRA in Northern Ireland, and ETA in Spain) and insurgencies that pursue a Maoist-type protracted warfare primarily in the countryside (e.g., FARC in Columbia, Sandinistas in Nicaragua, PKK in Turkey, Maoists in Nepal, EPLF in Eritrea).Footnote 16 In comparison to the former, the latter would be more interested in mobilizing rural and provincial women who would make resourceful and resilient combatants. These armed groups that need to replenish its ranks with a sustainable supply of recruits are likely to appeal to undereducated women who perceive them as the only platform to develop agency in a patriarchal society. Hence, there will be a positive and significant relationship between gender inequality and women’s participation in a group espousing such a platform and pursuing a protracted warfare.

Finally, women with different social backgrounds are likely to have distinct motives to participate in an armed group. The ability of an armed group to transcend class-based differences is central to its mobilization efforts among women.Footnote 17 For urbanized and educated women, joining a movement could be a culmination of their political activism and ideological commitment to progressive change. At the same time, a movement could be more gender-inclusive only if it manages to mobilize large numbers of provincial and undereducated women who lack similar levels of political efficacy and awareness. The ability of a movement to present itself as a medium of agency for women whose social roles are restricted to fertility and domestic labor could be central to this mobilization. As a result, women’s different life experiences and societal positions will directly shape their motives to join the insurgency. In particular, the pursuit of agency under patriarchal conditions will play a more direct role in the motives of women from lower-class backgrounds and lacking educational opportunities.

Ethnicized Gender Inequality

Gender inequality, the unequal allocation of resources and disadvantageous treatment on the basis of gender, has multiple dimensions concerning socioeconomic, cultural, and political affairs (Moghadam Reference Moghadam and Moghadam2007). Patriarchal systems and practices “in which men dominate, oppress and exploit women” generate the most egregious forms of gender inequality (Walby Reference Walby1989, 214). In societies characterized by “classical patriarchy,” women’s roles are defined as child rearing and household work (Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti1988). These societies have high levels of fertility and limited public presence of women (Caldwell Reference Caldwell1978).

Kurdish women, especially in rural areas, married at an earlier age and gave birth to a higher number of children than Turkish women (Gündüz-Hoşgör and Smits Reference Gündüz-Hoşgör, Smits and Moghadam2007; Koc, Hancioglu, and Cavlin Reference Koc, Hancioglu and Cavlin2008).Footnote 18 Cousin marriages and berdel that entailed the exchange of brides between two families were common (Ertem and Kocturk Reference Ertem and Kocturk2008). Young males of the family could be entrusted with carrying out “honor killings,” often with the complicity of state authorities (Sev’er and Yurdakul Reference Sev’er and Yurdakul2001). A significant number of young Kurdish women committed suicide in protest against arranged marriages and domestic violence (Altindag, Ozkan, and Oto Reference Altindag, Ozkan and Oto2005; Ziyalar, Sarıpınar, and Çalıcı Reference Ziyalar, Sarıpınar and Çalıcı2016). Moreover, the Kurdish-populated regions of Turkey exhibited lower levels of female literacy and women’s participation in the nonagricultural paid workforce (Kirdar 2008). Urban migration did not necessarily improve the status of Kurdish women whose participation in low-skilled and low-paid jobs without social security benefits (e.g., working in textile workshops) perpetuated their precariousness (Erman Reference Erman2001). In Kurdish cities, participation of urbanized women with limited education in labor force remained low (Dayıoğlu and Kırdar Reference Dayıoğlu and Kırdar2010, 73). Similar patterns of ethnicized gender inequality were also pronounced in Kurdish regions of Iran, Iraq, and Syria (Rasool and Payton Reference Rasool and Payton2014; Ahmadiet al. 2008).

The linguistic barrier has historically limited the effectiveness of the Turkish state’s modernist agenda, limited Kurdish women’s avenues of social mobility, and hampered inter-ethnic feminist alliances (Yüksel Reference Yüksel2006). By the late 1990s, around one-third of adult women in the eastern provinces did not speak Turkish (Gündüz-Hoşgör and Smits Reference Gündüz-Hoşgör, Smits and Moghadam2007, 191) and lacked access to state services (e.g., family planning) provided exclusively in Turkish (Yüceşahin and Özgür Reference Yüceşahin and Murat Özgür2008). While the successive governments aimed to increase the state capacity to subdue the insurgency, the gaps between eastern regions and the rest of country continued to persist (Gezici and Hewings Reference Gezici and Hewings2007). Furthermore, the Kurdish nationalist movement opposed the Turkish state’s campaigns of birth control and literacy as policies of assimilation (Açık Reference Açık, Gunes and Zeydanlioglu2014, 126). In this sociological context characterized by the intersection of gender and ethnic inequalities, the PKK’s gender narrative gradually found a receptive audience among undereducated and poor Kurdish women.

Research Design

The Kurdish Insurgency Militants (KIM) dataset,Footnote 19 one of the most comprehensive datasets about an insurgency, provides information about 1,385 female PKK militants killed between 1984 and 2016 (in addition to 7,808 male fighters). It represents more than 40% of the total PKK fatalities during this period.Footnote 20 Information about these fighters is obtained from short obituaries published by the PKK to honor its fallen fighters in its publications (e.g., Serxwebûn) and on its websites (e.g., www.hezenparastin.net), as well as online sources such as journalistic interviews with deceased militants. The dataset contains demographic information about the militants including their names, gender, and birth year and location, recruitment year and location, and death year and location. Additional pieces of information available for fewer militants involve their family’s socioeconomic status, education level and occupation at the time of recruitment, and experiences of state repression and political activism.

Certain types of militants are likely to be underrepresented in the KIM dataset. First, the militants who were unregistered by the insurgency and killed in internal purges are unlikely to be included in the dataset. Next, the surviving militants may have certain characteristics (e.g., being more skilled fighters) that set them apart from the ones who were killed. Third, information about the militants who died in the 1990s, when the armed clashes were most intense, is less complete than the other periods, as the recording capacity of the insurgency was overwhelmed. Fourth, militants with college education may receive greater coverage than undereducated militants in obituaries, as the insurgent leadership would like to highlight its ability to mobilize the former. This would make undereducated women underrepresented in the KIM dataset but would generate a bias against the theoretical expectation about the positive relationship between gender inequality and women’s recruitment into the PKK (i.e., making it easier to falsify this proposition). Finally, the PKK may have an incentive to over-report female fighters in its obituaries to achieve greater mobilization among women. However, the ratio of female obituaries is significantly lower than the typical estimates of the number of women in the PKK ranks.Footnote 21 Furthermore, the information obtained from the KIM is consistent with the information obtained from in-depth interviews. Both sources suggest a significant and sustained increase in the number of women combatants starting with the early 1990s.

In terms of qualitative research, this article utilizes sources in primary languages (i.e., PKK publications and journalistic reporting in Turkish and Kurdish) and in-depth interviews primarily with individuals whose close relatives joined the insurgency.Footnote 22 Most of these interviews took place in private settings in Turkey (Istanbul and Kurdish localities) in late 2012 during a time of intense clashes. Given security issues and the sensitivity of collecting information about active militants (Fujii Reference Fujii2010), I focused primarily on militants who already lost their lives. Interviewing relatives rather than militants during an active conflict reduces the probability of receiving “party-line” responses. These interviews helped me better flesh out dynamics characterizing their decision to join the insurgency. Furthermore, I pursued a sampling design to maximize variation in characteristics of both the families and militants. I met with families involved in solidarity associations close to the PKK, as well as politically more independent families, to gather information about individuals with diverse life histories and different views. In some cases, I was able to interview several family members multiple times over a period of multiple months. I decided to complete my interviews when I reached a saturation point regarding different paths to the insurgent recruitment.

I also conducted interviews with several former militants, two males and two females, to discuss the evolution of gender relations in the ranks. One of the interviewees was a renowned female commander who was actively involved in the formation of a separate women’s unit in the PKK. Three of these interviews were conducted in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2018, while the fourth was conducted over phone. These interviews helped me clarify some of the details concerning the emergence and rise of women fighters, the regulation of sexual affairs, and the internal tensions related to gender relations. The utilization of information from different sources and via different methods facilitates triangulation and reduces the likelihood of biased accounts. Overall, I conducted 73 interviews that provide fine-grained information about 20 female militants (in addition to 57 males). One of these women joined the insurgency in the 1980s, thirteen of them in the 1990s, and six of them after 1999.

The Rise of Women in the PKK

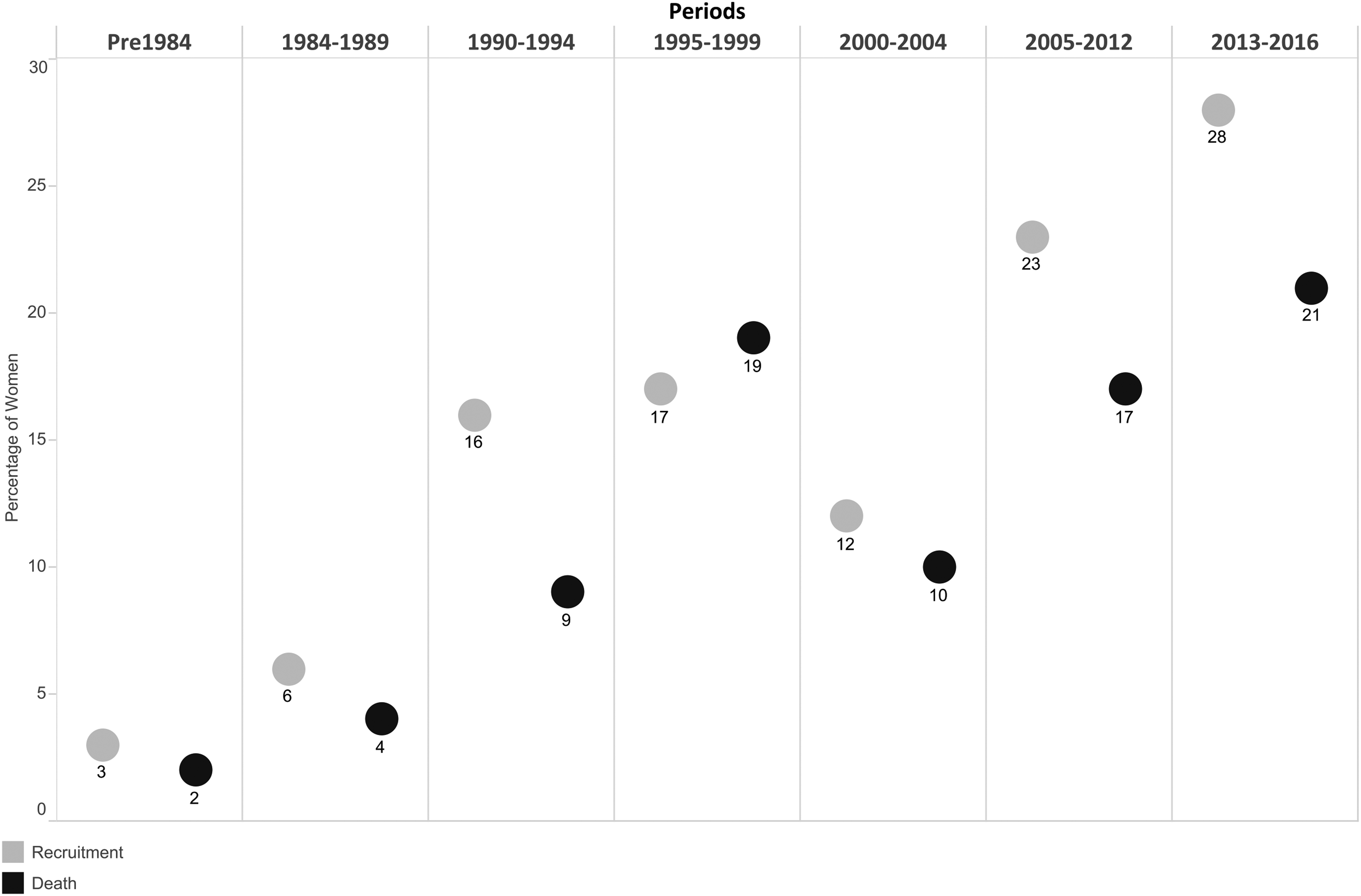

The PKK, formally established in 1978, did not have significant number of women fighters in its early years (Marcus Reference Marcus2007). Women who joined the PKK tended to be high school or college educated with a history of leftist activism.Footnote 23 Many of them were members of the Alevi Kurdish community characterized by less conservative gender relations than the Sunni Kurds.Footnote 24 This initial pattern is consistent with studies suggesting that educated and activist women are more likely to join an armed group (Thomas and Wood Reference Thomas and Wood2018). However, as the ratio of women within the PKK grew, their sociological backgrounds became more diverse. Figure 1 provides the percentages of females as PKK recruits (grey dots) and fatalities (black dots) in seven periods over three decades. The critical juncture took place in the early 1990s when the ratio of female combatants increased to 16%.Footnote 25 In the most recent period, 28% of recruits and 21% of deceased militants were women.Footnote 26 The actual percentage of women in the PKK ranks could be higher as women were more likely to be assigned to non-combat positions and tasks in camps.Footnote 27 In contrast, other Kurdish nationalist organizations such as KDP (Partiya Demokrat a Kurdistanê) and YNK (Yekîtiya Nîştimanîya Kurdistanê) have never had comparable levels of women fighters in their ranks (Nilsson Reference Nilsson2018). Similarly, paramilitary groups sponsored by the Turkish state among Kurdish villagers have had miniscule number of female members (Önder Reference Önder2015).

Figure 1 Recruitment and death of female PKK militants over time (in %)

Source: The KIM Dataset. The figure shows female militants as a percentage of all militants. Recruitment periods of 1,719 out of 9,196 militants are missing. The gender of three militants are unknown. The numbers in the last period, 2013-2016, do not include women in the PKK’s urban wing that engaged in heavy battles with the Turkish security forces in 2015 and 2016.

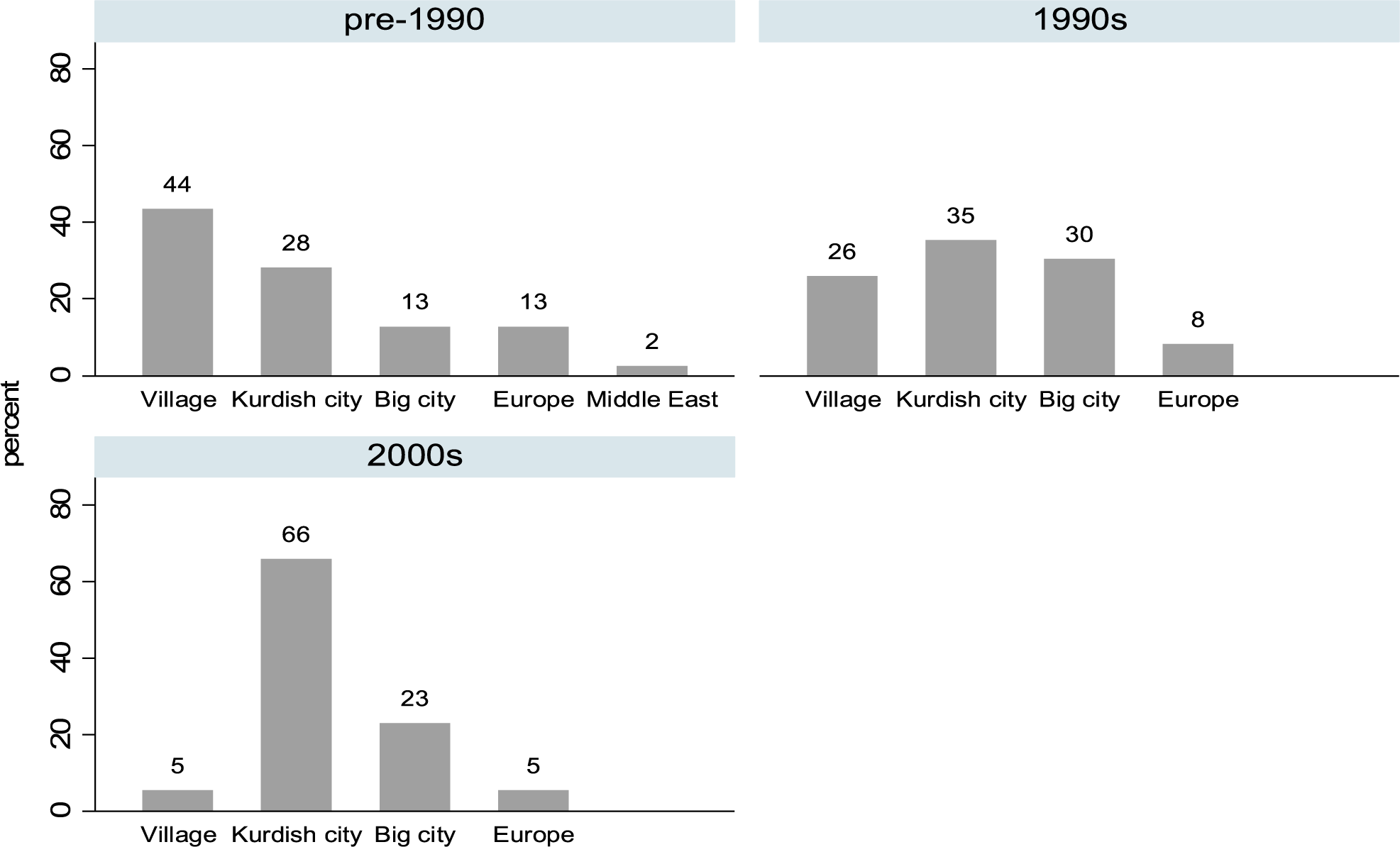

The composition of women in the PKK also evolved reflecting broader societal changes. Figure 2 demonstrates the recruitment of locations of PKK women in three different periods. Before the advent of 1990s, a plurality of women joined the PKK from rural areas. The ratio of village recruits consistently decreased in the more recent periods. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, however the PKK recruited an overwhelming majority of its recruits from urbanized areas. This change reflected rapid urbanization of the Kurdish society as a result of both economic and political dynamics starting in the 1990s. While some of these recruits joined from large Turkish-majority cities (“big cities”) such as İstanbul, İzmir, and Mersin, others were residents of much smaller cities in predominantly Kurdish southeastern part of the country. As discussed later, women from different backgrounds had distinct motives to join the PKK.

Figure 2 Recruitment places of female PKK militants over three periods

Source: The KIM Dataset. N=454. The change in recruitment location patterns are similar for male recruits. Kurdish cities are primarily located in southern Turkey and range from small towns with several thousand residents to larger urban centers with a population of several hundred thousand (e.g., Diyarbakır). Big cities are large urban metropolises of Turkey such as Istanbul, Izmir, and Mersin. The Europe category includes the Kurdish diaspora in Western European countries such as Germany. The Middle East category includes countries in the region without large Kurdish minorities (e.g., Lebanon).

The participation of large numbers of women in the ranks presented unique challenges for the insurgency. Narratives aiming to generate contentious action are likely to become successful when they resonate with the preexisting meanings among targeted communities (Simmons Reference Simmons2016, 64; Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011). Yet the rise of a mixed-gender insurgency was a highly unsettling development and risked backlash in a tribal society characterized by a strictly gendered division of public/male and private/female space. When a woman militant returned home, the first question she faced from her mother was “whether she slept with a man in the ranks.” For her mother, her identity as a fighter was acceptable, but not her identity as a woman having a relationship outside of wedlock (Interview I; details about interviews cited in the article provided in table C.1 of the online appendix). This tension between the insurgent promise of gender equality and prevailing gender norms necessitated important compromises by the insurgent leadership. The PKK portrayed women fighters as asexual beings dedicated to the collective wellbeing.Footnote 28 In an attempt to appease the conservative Kurdish population, it propagated an image of young men and women fighting shoulder to shoulder without any romantic or sexual interactions. Abdullah Öcalan, the PKK leader, explicitly characterized sexual liberation as a form of “bourgeoisie freedom” and associated it with a counter-revolutionary stance (Öcalan Reference Öcalan1989, 12). While other armed groups with large numbers of women, such as the EPLF in Eritrea or the RUF in Sierra Leone, allowed for marriages among their fighters,Footnote 29 the PKK strictly prohibited romantic relations among its male and female combatants (Solina Reference Solina1997, 43, 144).Footnote 30 Fighters having romantic and sexual affairs with each other were subject to sanctions such as detention and demotion in ranks (Interview LXX).Footnote 31 Furthermore, the PKK, despite its strong opposition to marriage as a backward institution, rarely recruited married women (or men) as full-time fighters.Footnote 32

Explaining Women’s Violent Mobilization

The significant participation of women in the PKK starting in the early 1990s requires an explanation combining both organizational and societal factors. My analysis proceeds in two steps. First, I discuss the dynamics characterizing the PKK’s pursuit of women fighters. I then shift the focus to the recruitment motives of women. Consistent with the first theoretical proposition, the emergence of a distinctive PKK narrative on the “woman question” preceded its success in recruiting women. This gender narrative clearly set the PKK apart from the KDP and YNK which had a longer organizational history but much limited number of female fighters.Footnote 33 A systematic analysis of the PKK’s official monthly magazine, Serxwebûn, demonstrates that the PKK started to cover the question of woman’s emancipation in Kurdish society and its relevance for the nationalist struggle only in 1987.Footnote 34 Öcalan wrote a series of articles sharply critical of the traditional family structure confining women to a life of domestic labor, equating honor with a woman’s body, and hampering his efforts to mobilize fighters.Footnote 35 Echoing Frantz Fanon, he characterized Kurdish men as little despots who suffered under Turkish colonialism but dominated and abused women in their family (Fanon Reference Fanon1963). He argued that the only way to protect collective honor was through armed struggle leading to an independent Kurdistan. He was also critical of liberal feminism, observed that women made only limited gains under socialism, and identified national, class, and gender identities as distinct sources of oppression. From his perspective, Kurdish women had stronger reasons to participate in the nationalist armed struggle that would bring their emancipation from triple oppression. He developed the notion of “killing manhood” signifying his categorical opposition to the patriarchal head of household and encouraged his followers to eschew traditional family roles (Çağlayan Reference Çağlayan2012, 20-1). These ideas were incorporated into the PKK’s ideological corpus and covered extensively in training sessions. By 1991, Öcalan advocated mass participation of young women in the party ranks and the replacement of familial loyalties by a total commitment to the national struggle. Similar to women’s movements that reconfigured social notions of femininity, Öcalan’s PKK offered a new avenue of public role for Kurdish women.

Öcalan also saw women’s mobilization as an opportunity to consolidate his authority vis-à-vis his rivals and sought to cultivate women militants’ unquestioned loyalty to his leadership. In the eyes of a former male commander who joined in 1991, women were “his eyes and ears” within the insurgency (Interview LXXI). Meanwhile, women militants leveraged his patronage to overcome opposition from men threatened with the rise of autonomous women’s military units. After the capture of Öcalan in 1999, however, the old male guard of the insurgency defeated women combatants’ greater bid for autonomy and gradually consolidated their power within the insurgency (Interview LXIII).

Another organizational reason concerns the PKK’s need for greater human resources with the intensification of warfare. It established a “people’s liberation army” with a centralized command and the goal of pursuing a long war of attrition with the Turkish state in 1986.Footnote 36 While the PKK was initially logistically unprepared to accept so many women as combatants, the large-scale clashes starting with 1992 made it a practical necessity. Women’s participation not only contributed to war efforts in significant ways but also helped the PKK leadership obtain greater performance and loyalty from men by stoking rivalry between genders (Interviews LXXII and LXXIII). Women fighters also became gradually more assertive. A separate political unit for women within the PKK was established in November 1993. Women combat units became operational in 1994. A “women’s army” with an inaugural conference was established a year later. Over time, the images of PKK women actively engaging in combat missions had impact on how the status of women were perceived in the Kurdish society. Women who committed acts of self-sacrifice such as self-immolations and suicide bombings emerged as the icons of the nationalist struggle.Footnote 37

As discussed earlier, previous scholarship identifies three gender-specific explanations about women’s motives to join an armed group. There is limited empirical evidence supporting the dismantling of traditional family structures as a primary explanation in the case of the PKK women for two reasons.Footnote 38 First, women’s mobilization in large numbers preceded the intensification of counterinsurgency policies characterized by systematic village evacuations, mass arrests, and extrajudicial killings by 1993 (Belge Reference Belge2016). Next, while many female recruits came from displaced families who were exposed to violence, male family members were still present. Only few recruits came from female-led households according to the KIM dataset.

It is difficult to offer a direct test of the sexual violence explanation.Footnote 39 Victims and their relatives were often very reluctant to tell their stories given the continuing fear of the state and the prevailing cultural norms constructing family honor through women’s body (Aras Reference Aras2014, 92-3).Footnote 40 At the same time, it is possible to empirically test whether the PKK used sexual violence as a recruitment narrative. If PKK utilized stories of sexual violence by security forces as a recruiting tool to attract women to its ranks similar to that of the FMLN, one would expect to detect a coincidence between the timing of these narratives and women’s participation in the PKK ranks.Footnote 41 In fact, Serxwebûn had a wide coverage of sexual assaults during village raids, sexual abuse, rape, or threats of rape of detainees and women from families suspected to collaborate with the insurgents. Yet there is a no temporal coincidence between its coverage and women joining the PKK in large numbers. As shown in figure 3, the incidents of sexual violence as reported by the magazine and the actual numbers of female insurgent recruitment clearly diverged. While the latter became more significant only in 1990, most incidents mentioned by the magazine were from 1984-1986.

Figure 3 The recruitment of women fighters and the PKK’s reports on sexual violence

Source: The KIM Dataset and Serxwebûn.

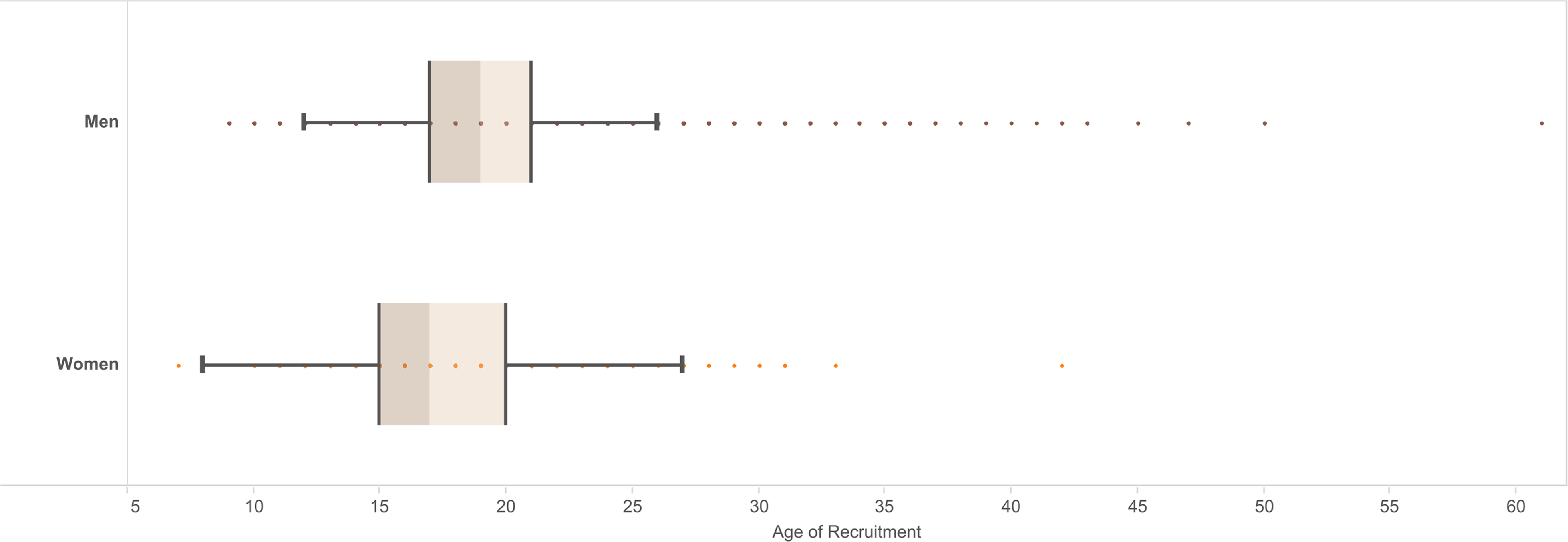

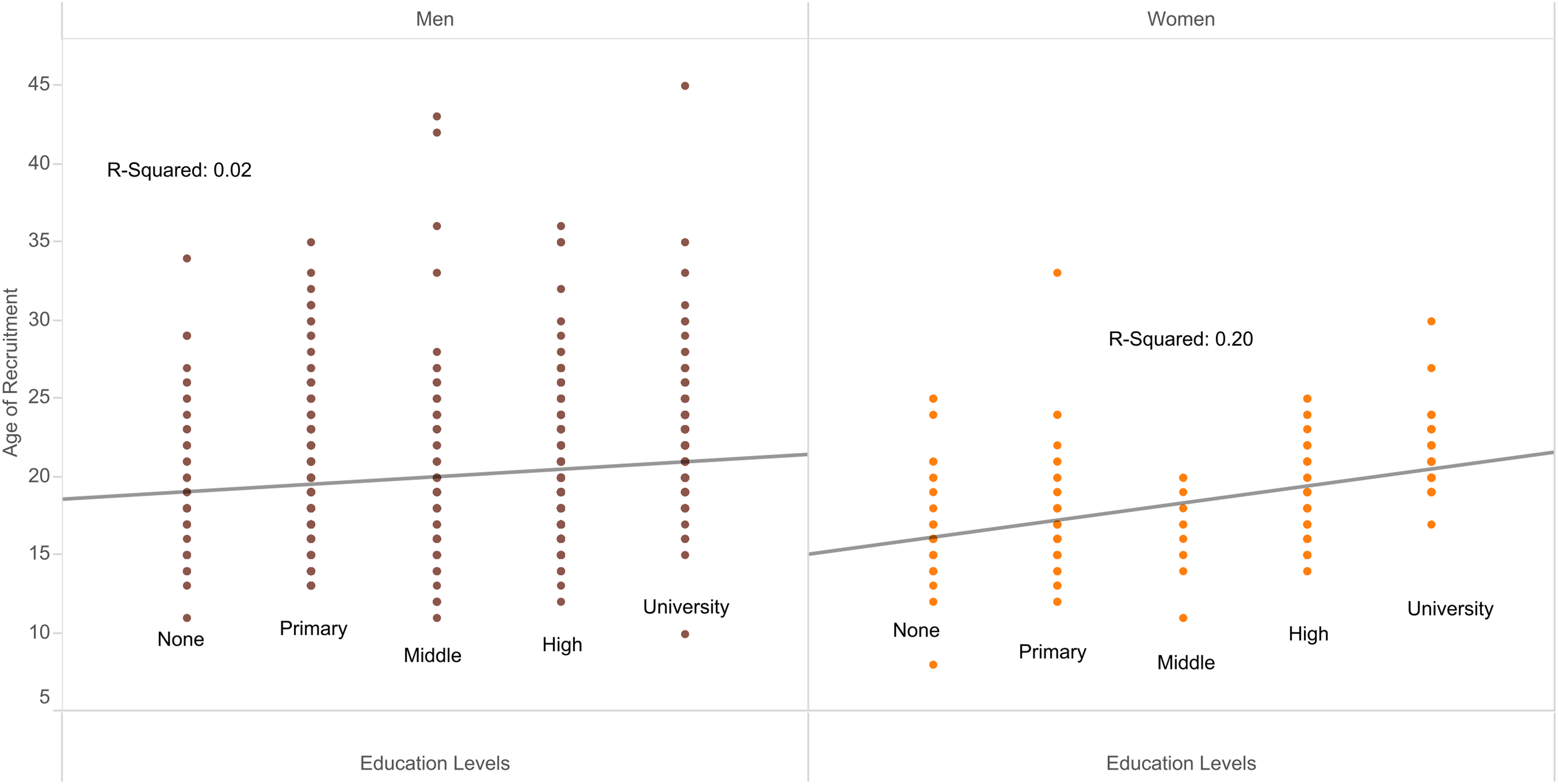

A third explanation concerns the impact of patriarchal relations on women’s mobilization. While few women who joined the PKK in the 1970s tended to be urbanized, educated, and activist, the late 1980s and 1990s saw the recruitment of large numbers of undereducated women from rural areas and provincial towns. Empirical evidence supports the contention that experiences of patriarchy directly shaped mobilization of the more recent recruits. First, as mentioned earlier, many Kurdish women married at a very a young age, moved to the household of their husband, and had a life dedicated to domestic labor and child rearing. For those women, joining the PKK could be the most viable way out of these relations (i.e., arranged marriages).Footnote 42 An implication of this argument is that women would join the PKK at a very young age (i.e., before being married). In fact, the average female recruitment age was significantly lower than that of males, as visualized in figure 4 (18 for females and 19.5 for males, a difference significant at ρ < 0.001). These statistics show that PKK female combatants were dissimilar to Chechen and Palestinian female suicide bombers who tended to be older widows and divorcees (Bloom Reference Bloom2005; O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke2009).

Figure 4 Box plots showing recruitment age for female and male PKK militants

Source: The KIM Dataset. The difference between female and male recruitment age is significant at p<0.001 level (one-tailed test). The median recruitment age of females and males is 17 and 19, respectively.

Next, for undereducated women, joining the PKK would be a vehicle of social mobility. The lack of professional skills and access to education did not prevent them reaching leadership positions. There is a very low correlation between the rank of the PKK fighters and their educational attainment (c = 0.04 for all militants, n=1,473 and c = 0.05 for women, n=231). Among thirty-eight highest-raking female commanders recorded in the KIM, twenty-five of them had no university education. Only five of them had some university education at the time of their recruitment. Some of the top female commanders joined the ranks as illiterate villagers and climbed up the ranks over years. One of them, who became one of the first female commanders in 1993, was an illiterate villager when she joined the PKK at the age of 14 in 1990. Finally, statistical analyses at an aggregate level (presented in detail in online appendix E) suggest that there is a significant and negative relationship between PKK’s recruitment of women and the ratio of female to total literacy in Kurdish majority districts of Turkey from 1984 to 2016. As the latter increases, the former declines, controlling for a variety of political, socioeconomic, and historical factors. These empirical patterns, together, suggest that many women joined the PKK to liberate themselves from social conditions that can be labelled as “classical patriarchy.” At the same time, the PKK also mobilized educated women with greater life opportunities. The next section utilizes data from interviews to flesh out how women’s different life experiences and marginalization affected their participation in the PKK.

Different Patterns of Women’s Violent Mobilization

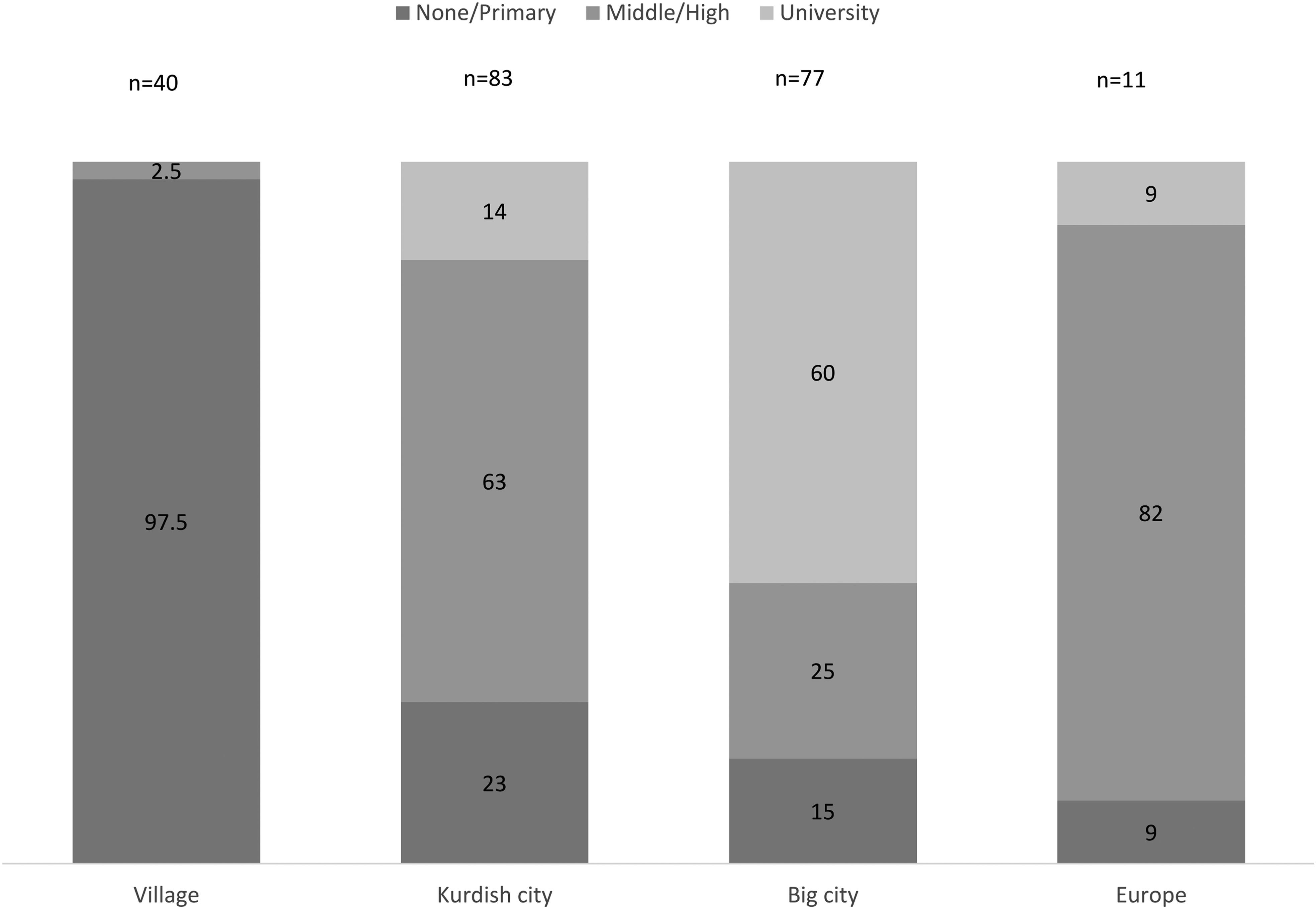

The PKK attracted women with different life experiences and pursued a more diverse recruitment strategy than other violent organizations that attracted primarily educated women (Krueger and Malečková Reference Krueger and Malečková.2003). While 60% of women recruited in major urban centers of Turkey had college education, 97.5% of rural recruits had either no schooling or only primary education (figure 5).Footnote 43 Moreover, younger women with educational attainments, and elder and married women with low educational levels were less likely to join the insurgency. Undereducated women were more likely to join the insurgency at an early age than educated women, as demonstrated in figure 6. The correlation between education and age was much weaker among male recruits. Besides, educated and urbanized women recruited in cities were more likely to have a history of political activism than women recruits from rural areas with lower levels of education. Forty-two percent of women who joined from big cities engaged in political activism prior to their recruitment, as opposed to 13% of women who joined the PKK from villages. Similarly, 58% of female fighters with university education (n=139) had a history of political activism, as opposed to 28% of female fighters with no schooling or primary school education (n=78).

Figure 5 Educational levels and location of recruitments of women fighters (in %)

Source: The KIM Dataset. The numbers represent percentages for each education category in each location of recruitment (LOR). Education information is available for 231 female PKK militants (out of a sample of 1,385). LOR is available for 478 of them.

Figure 6 Age and education levels at the time of recruitment for both genders

Source: The KIM Dataset. The age and education level at the time of recruitment are available for 201 female and 997 male militants.

The fine-grained information obtained from interviews shows a similar pattern. Out of twenty female militants, only two of them had college education (10%); six of them attended high or middle school (30%); others had either no schooling or primary school education (60%). Twelve of them were political activists before joining the PKK. More than 50% of males with primary school education or no schooling (14 out of 28) engaged in political activism prior to recruitment. Yet only one of the women with primary school education or no schooling was an activist. These empirical patterns suggest two distinctive types of female recruits: educated and urbanized women with a history of activism and undereducated and mostly rural women with no such history. Factors such as exposure to state violence and familial loyalties often played important roles in the mobilization of both types of women. At the same time, they had also their distinct motives to fight reflecting their particular experiences of ethnicity, class, and gender based inequality, as suggested by the notion of intersectionality.

Undereducated Women Recruits

Interviews reveal how young girls perceived the insurgency as a way to liberate themselves from restrictive gender roles equating womanhood with fertility and domestic labor. Zin was the eldest of twelve children of a peasant family and had no schooling (Interview LXIII). Her family had neither political affiliation nor experience of state repression. Female militants who visited her village when she was a small child left a deep impression on her mind. When Zin was 11 years old, her family migrated to a Kurdish city for economic reasons. She mostly stayed home, helped with household chores, and took care of her younger siblings. She also made beautiful embroidery. According her parents, who were cousins, she did not participate in any political events or demonstrations. One day, she told her mother that “whatever I do at home, I am not satisfied. I do embroidery not to get married but just to spend time.” Shortly after, she disappeared. Her family later learned that she joined the PKK. She stayed in the ranks for twelve years before being killed in a skirmish. As an illiterate 17-year-old Kurdish girl from a family of modest means, her only alternative life prospect was an arranged marriage.

Binevş was an illiterate stay-at-home woman who was taking care of her younger brothers in Diyarbakır. Her father did not send her to school and expected her to marry at an early age (Interview LVII). Similar to Zin, she also encountered female militants as a child and was impressed by their confidence and aura. In the words of Binevş’s father, “people talked about the heroism of women guerillas at a time when there were heavy clashes. My daughter, who had no schooling, was deeply influenced by them.” One day, she left for the mountains with a small group of girls. Binevş died in a suicide mission in 1998, four years after joining the insurgents.

In the words of a woman who joined the insurgency at the age of 12, “where I was born, they married girls when they were 11–12 years old. I wanted to go to school; my father did not let me. I am not sure if I would have joined the ranks had I gone to school” (Bingöl Reference Bingöl2016, 65-74). A female PKK commander, she linked her decision to join the ranks at the age of 16 in 1990 to her family’s attempt to marry her forcefully (Demir Reference Demir2014, 11-30). Similarly, a female fighter from Iran explained her decision to join the militants by saying, “women are like a commodity and do not have any human rights. My father or brother could force me to marry a 60-years-old man.”Footnote 44 These stories exemplify how the pursuit of agency was a crucial factor in the decision to join the insurgents among lower-class Kurdish women with very limited life options.

Educated Women Recruits

Women with high access to higher levels of education had a different pattern of mobilization. For them, the choice was not between taking arms and a life of patriarchal subordination. While they were also subject to various forms of pervasive gender inequality (i.e., lower employment opportunities than men, unequal division of labor in marriage, domestic violence), most of them already developed a sense of political agency via activism prior to their violent mobilization. For these women, joining the insurgency was typically a gradual culmination of their activism. They often developed radicalized political identities in the face of state repression and discriminatory practices.Footnote 45 “My daughter grew up in big cities … She was detained several times for her activism. In 2004, she and her friends became human shields to prevent the clashes between the soldiers and guerillas. Then they made a collective decision to join the guerillas” (Interview LXIV). “My daughter was active in the student association in the university when she was arrested. She felt humiliated when the police took her in handcuffs to take her exams to the university. She joined the guerillas soon after (Interview L).

Gender inequality played a role also in the mobilization of educated women but in very different ways than the mobilization of women living under patriarchy. “When I was a high school student, I took my mother to a doctor who was also an ethnic Kurd. My mother spoke Kurdish but the doctor did not pay attention to her. He expected me to explain her health problem. She felt humiliated. My father had been arrested several times for his political activism, but this was the first time I experienced a deep sense of injustice … I came to know the PKK after attending the university. I was arrested twice because of my activism. We had long discussions about the national liberation and women’s status in society. Later we joined the PKK as a group of several dozens of college attending women” (Interview LXXIII). Sakine’s visceral experience of her mother’s marginalization because of her inability to speak Turkish (an example of how ethnic inequality aggravates gender inequality) fueled her moral outrage and became the basis of her violent mobilization years later.

At the same time, the availability of educational opportunities could provide women subject to patriarchy with means to develop agency other than joining the insurgents. Hanim was born into a highly conservative Kurdish family who moved to Istanbul because of a blood feud (Interviews LXII and LXVII). She had five sisters. Her father married for a second time because her mother did not give birth to a son.Footnote 46 He opposed girls’ education and had most of his daughters married as teenagers. One of the sisters achieved outstanding success in a middle school entrance exam in the early 1990s. She joined the militants when her father did not allow her to study. In the face of patriarchal practices in her family, Hanim also decided to join the insurgency several years later but was caught. After her release from prison, she dedicated herself to her studies and received a fellowship to study in a prominent university.

Conclusion

I suggest that a more comprehensive understanding of women’s participation in insurgencies, which is central to the resolution of armed conflicts and the prevention of the recurrence of violence, requires systematic analyses of multiple forms of unequal relationships based on ethnicity, gender, and class. The PKK extended its popular base and became more resilient by developing a discourse of gender emancipation and mobilizing large numbers of women in a context where gender/ethnic inequalities intersect. In particular, uneducated women lacking decision-making power over their lives found armed struggle appealing because it provided them with the most viable way out of patriarchal relations.Footnote 47

My findings provide three broader insights that could be incorporated into comparative studies of women’s violent mobilization. First, women’s participation in armed groups fighting on behalf of a marginalized group would be higher if gender inequality is also higher within this group compared to the rest of society. For this reason, it is crucial to study gender inequality at the group level rather than at the national level. Next, insurgencies that wage a protracted war of attrition have a stronger incentive to mobilize a greater number of women than smaller and primarily urbanite groups. While the latter would recruit overwhelmingly among activist and educated women, the former would need to reach out to undereducated and provincial women for their own sustainability and organizational interests. Consequently, there would be a significant and positive relationship between socioeconomic indicators of gender inequality (e.g., fertility, education, and participation in labor force) and women’s participation in large insurgencies pursuing popular mobilization (but not necessarily in smaller ones). Finally, the ability of an insurgency to mobilize women living under patriarchy ultimately depends on its management of the potential backlash from its base and tensions within the ranks. Comparative perspectives regarding these internal insurgent dynamics will be highly informative in this regard.

Finally, I point out a complicated relationship between women’s political agency and empowerment. Women’s participation in the PKK has shaped gender relations even if its emancipatory potential remains limited.Footnote 48 On the one hand, violent mobilization and political sacrifices of women fighters have gradually opened up more spaces and leadership positions for a large number of women activists and politicians in non-violent spheres (Watts Reference Watts2010). The Kurdish nationalist organizations and parties, which adopted a quota system, have the highest ratio of women in leadership positions in contemporary Turkish and Syrian politics (Sahin-Mencutek Reference Sahin-Mencutek2016).Footnote 49 The visible and active presence of Kurdish women in many different aspects of public life demonstrates the lasting legacy of women’s initial mobilization by the PKK.Footnote 50 This pattern is consistent with historical patterns where sacrificing one’s life for one’s country and community has been the precondition of access to greater rights but not equality (Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg2010; Yuval Davis Reference Yuval-Davis2011, 103). It also suggests how a highly unconventional route for liberal feminism could contribute to agency of women subject to multiple forms of ethnic, class, and gender-based inequalities.Footnote 51 On the other hand, political activism involving self-sacrifice by many women does not necessarily lead to an improvement in other aspects of gender inequality. Kurdish women pursue gender equality and autonomy outside of the boundaries of the nationalist agenda remain marginalized and excluded (Weiss Reference Weiss2010; Açık Reference Açık, Gunes and Zeydanlioglu2014). Furthermore, women who leave the insurgency end up being homemakers dependent on the income of their husbands.Footnote 52 Consequently, the relationship between women’s political agency and long-term empowerment remains highly tenuous.Footnote 53

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Ethnicized Gender Inequality and Women’s Violent Mobilization in Turkey

Appendix B. PKK’s Gender Narrative during its Formative Years

Appendix C. In-Depth Interviews

Appendix D. The KIM Dataset Supplementary Figures

Appendix E. District Level Analysis

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https:/n/doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719000288