Introduction

Spirituality is at the core of the definition of whole-person palliative care (Steinhauser et al. Reference Steinhauser, Fitchett and Handzo2017). Providing spiritual care, or attending to the spiritual needs of patients, is now identified as a core domain by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization , 2018a). Spiritual needs are the needs and hopes of finding meaning and purpose in life, as well as the need to relate to others, God, religion, well-being, and communication, and to be treated like a normal person (Mesquita et al. Reference Mesquita, Chaves and Barros2017). Patients’ spiritual needs fall into several dimensions. The most commonly recognized domain is the need to find a meaning and purpose in life. The need for love, peace, belonging/connectedness, and forgiveness is also quite common (Flannelly et al. Reference Flannelly, Galek and Bucchino2006). In this study, spiritual needs are defined as the needs and expectations which humans have to find meaning and goals in life, love and forgiveness, hope and encouragement, and faith and religion. It is necessary to know what the spiritual needs of patients are to be able to provide appropriate interventions to meet the patients’ spiritual needs. Therefore, the patients’ spiritual needs should be identified and registered nurses must have an understanding of the spiritual needs of terminally ill cancer patients and families to provide efficient care. Arrey et al. (Reference Arrey, Bilsen and Lacor2016) also claimed that spiritual needs are related to patients’ diseases, which can affect their well-being, and the failure to meet these needs may impact their quality of life (QOL).

Spirituality is a critical resource in coping with illness and is an important component of QOL. Spirituality and coping with chronic medical diseases through the reduction of anxiety and depression and sharing a strong association can result in the improvement of the quality of mental and physical life (Jafari et al. Reference Jafari, Farajzadegan and Loghmani2014). Patients with potentially life-limiting diseases, such as HIV or cancer, may face deep existential challenges in relation to their body, time, others, and approaching death. Individuals with advanced diseases face existential challenges due to the disease’s progression as they experience increasing dependency and loss of autonomy, which challenge their dignity, integrity, and identity. Simultaneously, they are also confronting existential challenges in relation to their mortality, such as the fears and feelings of uncertainty surrounding their impending death (Tarbi and Meghani Reference Tarbi and Meghani2019). This is especially true for patients facing the end stage of a terminal disease with symptoms of physical, psychological, and spiritual suffering, which create spiritual grief and diminish spiritual well-being (SWB). SWB is threatened by experiencing illness and treatment, but its correlation with other illness symptoms and the efficacy of palliative care (Rabow and Knish Reference Rabow and Knish2015) is unclear. Previous studies have shown that SWB is a strong predictor of perceived QOL in patients receiving palliative care. SWB appears to potentially be a protective factor against psychological distress at the end of life (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, Strasser and Gamondi2017). It has also been reported to be a significant predictor of the effectiveness of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer (Chaiviboontham Reference Chaiviboontham2015).

There is a growing interest in palliative care in Thailand. The palliative care services in some areas were not integrated with the overall health service system. The palliative care model in Thailand is diverse and includes care performed by home-based, hospital-based, faith-based, and hospice (Pokpalagon Reference Pokpalagon2016) groups. Prior studies that have been conducted in Thailand have predominately taken place within only one or 2 settings. Those studies found that the SWB of patients with terminal cancer in cancer centers and tertiary hospitals were moderate to high (Get-Kong et al. Reference Get-Kong, Hanucharurnkul and McCorkle2010; Rattanil and Kespichayawattana Reference Rattanil and Kespichayawattana2016), while the SWB of patients with terminal illnesses in community hospitals and faith-based organizations were high (Kinawong and Khoenpetch Reference Kinawong and Khoenpetch2016; Tantitrakul and Thanasilp Reference Tantitrakul and Thanasilp2009). However, little is known about the outcomes of palliative care in terms of spiritual needs and SWB in various settings (i.e., community/home-based care (Home), faith-based organizations, and hospice wards) as a rigorous comparison of the spiritual needs and SWB within these settings is yet to be conducted. Confronted with life-limiting or terminal illnesses, many terminally ill patients have to deal with coping, discomfort, and dissatisfaction. Terminal illnesses can cause patients to have unmet spiritual needs. This spiritual conflict may result in the SWB of the patients. This study explores the spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of patients with terminal illnesses in 4 different care settings to determine how the differences may be related to their spiritual needs, well-being, and Buddhist practices.

From a Thai perspective, SWB can be defined as a multidimensional concept of wisdom, or a mental state, in relation to a religious view that leads to peace, happiness, and enlightenment (Chaiviboontham et al. Reference Chaiviboontham, Phinitkhajorndech and Hanucharurnkul2016). Thailand is a stronghold of Theravada Buddhism and 94% of the population is Buddhist (Winzer et al. Reference Winzer, Samutachak and Gray2018). The basic principles of dharma, the law of karma, helps Buddhists do well and practice Buddhism in their daily lives. Buddhist practice is based on 3 practical steps: namely, morality (Sīla), concentration (Samādhi), and wisdom (Paññā). Chimluang et al. (Reference Chimluang, Thanasilp and Akkayagorn2017) examined the effects of interventions based on Buddhist principles in patients with terminal cancer and found that the SWB of the participants in the experimental group was significantly higher than that of participants in the control group (Chimluang et al. Reference Chimluang, Thanasilp and Akkayagorn2017). However, their results are limited because they used a small sample and only included patients with terminal cancer. Thus, there is a need for further study with patients having additional terminal illnesses.

Differences in care services and contexts may result in different outcomes. These differences may be related to the spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of patients with terminal illnesses. Most studies have been confined to a single setting, such as faith-based organizations, community hospitals, and cancer center hospices, rather than offering a rigorous comparison with other settings. Thus, there is limited evidence of the relative benefits of the different contexts in terms of spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices. The settings in this study were selected using purposive sampling. A faith-based organization for patients with AIDS (FB_AIDS) was established for people with AIDS in the year 1992, with monks and volunteers from both Thailand and abroad. A hospice ward (Hospice), Thailand’s first government hospice, was established with 16 beds for hospice care in 1998. A faith-based organization for patients with cancer (FB_CA) provided palliative care to people with cancer since 2005, with harmonious integration between conventional and traditional Thai medicine. The Home was an established palliative care clinic led by an Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) since 2008. These settings are the first organizations having continuously provided palliative care to people and widely recognized in Thailand. Even though these 4 settings provided care in different contexts, they all focus on improving QOL and SWB based on Buddhist practices This study explores the spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of patients with terminal illnesses receiving care in a Home, FB_AIDS, FB_CA, and Hospice in a cancer center. This study will help practitioners to better understand the spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of terminally ill patients. Therefore, health personnel can apply the research results for taking care of terminally ill patients, and it can be used as a guideline to provide efficient palliative care for patients with terminal illnesses. Nursing professionals should investigate the spiritual needs of terminally ill patients, which encourage the patients to achieve holistic care and promote SWB of patients.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional quantitative descriptive design was used to explore the characteristics, spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of patients with terminal illnesses receiving care in a Home, FB_AIDS, FB_CA, and Hospice. The study also compared the differences in the spiritual needs, SWB, and Buddhist practices of patients with terminal illnesses in each care setting.

Sample and settings

The study included patients with a terminal illness receiving care in one of the following 4 settings: Home, FB_AIDS, FB_CA, and Hospice. The sample size was determined via estimation of the population proportion from each of the selected study sites (Viwatwongkasem Reference Viwatwongkasem1994), resulting in a need for 170 subjects (30 from Home, 33 from FB_AIDS, 64 from FB_CA, and 43 from Hospice).

Home refers to care provided by a community hospital located in Northeastern Thailand with an inpatient capacity of 60 beds and that is known to offer palliative care services. The hospital’s palliative care clinic has been established since 2008 and is led by an APN. Palliative care is provided in inpatient, outpatient, and home care settings. If the patients stay at home and had uncontrolled symptoms, they had to be admitted to hospital, and after all symptoms are under control, they must be back to their homes. In this study, most of them are treated in their homes rather than in the hospital. Therefore, the APN and the palliative care team provided most of the services through home visits. The APN worked with physicians to provide medical care and coordinated with pharmacists to manage the medications and supplies for continuing care. The APN administered care via home-based interventions; provided direct care, including psychosocial support and patient education; and provided support and skill training for patients’ relatives to enable them to take care of patients at home, such as training related to pain management, oxygen therapy, wound care, and feeding. The services also included providing counseling to patients and relatives directly and by phone 24 hours a day. There were also village health volunteers (VHVs) to assist patients and their relatives. The VHVs provided support through religious practices or beliefs, such as chanting, meditation, and giving alms. In addition, the equipment required to make caring the patients at home possible was available and could be borrowed from the hospital.

The FB_AIDS is a nonprofit organization located in the central region of Thailand, which was started by Buddhist monks to provide hospice care to AIDS patients in 1992. Comprehensive health care is provided by monks, professional health-care providers, and volunteers, and it provides an excellent skill mix to deal with the biopsychosocial aspects of health. The FB_AIDS is funded through financial support from the Thai government and donations (World Health Organization 2018b). There are 56 beds for dependent patients and housing for 60–70 independent patients at the facility. There are 2 providers who are trained to care for patients on duty 24 hours a day. The independent patients also volunteer to take care of patients who need help. The FB_AIDS has a strong network with the tertiary hospital for the local provinces. The patients are checked regularly by physicians and registered nurses every month, and, in case of an emergency, patients can be directly referred to the hospital. With regard to religious practices, the patients can chant and meditate as needed. The monk who established the FB_AIDS lives in the temple and meets with the patients to perform blessings.

The FB_CA is a nonprofit organization located in a Buddhist temple in Northeastern Thailand. Buddhist monks established this organization in 2004 with a strong desire to provide care for patients with cancer based on Buddhism and the use of Thai herbal medicines. Care provided by the FB_CA combines various methods of healing, such as Thai traditional medicines, Western medicines, and alternative therapies including meditation, natural herbs, herbal saunas, breathing, diet, music, humor, group support, healing touch, and chanting. Religious activities are organized to cultivate faith and encourage patients to fight the illness. One important ritual is boiling herbs and the confession process. In the confession process, the patients write a letter about something they have done wrong and ask for forgiveness. Chanting and a blessing for the herbal preparation are then offered by the monk. The FB_CA uses Lord Buddha’s teachings to enhance the patients’ faith, hope, and acceptance of life in a peaceful environment. A sense of sharing and healing was evident as volunteers, patients, and families participated in activities together in a community of mutual assistance. The FB_CA’s sole source of funding is through financial support from donations (Pokpalagon Reference Pokpalagon2016; Pokpalagon et al. Reference Pokpalagon, Hanucharurnkul and McCorkle2012).

The Hospice is located in a cancer center in the central region of Thailand and provides inpatient palliative care services to cancer patients in the later stages of the disease. The Hospice admits patients for about 2 weeks. During this admission, the family can stay with the patient and the nurses teach the patients’ caregivers how to continue the care at home. The cancer center hospice has a peaceful atmosphere, is close to nature, and accommodates cooking and chanting. An interdisciplinary palliative care team is also available. The core team includes a physician, nurses, a social worker, a specialist in pain and symptom management, and a Buddhist monk. The Hospice organizes activities to support religious practices or beliefs, such as chanting, meditation, and inviting monks to receive food. However, most of the patients tended to stay in bed and not participate in any of the activities (Pokpalagon et al. Reference Pokpalagon, Hanucharurnkul and McCorkle2012).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in our study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age so that participants were old enough to provide legal consent, were willing to participate in the study, have been receiving care in one of the 4 selected settings for no less than 3 days so that the results could reflect the outcomes from each setting, were not having any severe symptoms during the study, and have the ability to speak, read, and write the Thai language. Patients who were not available at the time of study recruitment, or those refusing to take part or sign the consent form, were excluded. Twelve (n = 12; 6.5%) of the 184 eligible subjects did not include in the study because of feeling too ill/fatigued. In addition, 2 (1.1%) failed to complete the questionnaire because of feeling too ill/fatigued, resulting in 170 participants completing the study.

Ethical considerations

The study was assessed by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine at Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (report no. ID 11-57-80). All participants were informed about the objectives and procedures of this project and completed written consent forms. The participants were assured of their confidentiality and right to withdraw at any time throughout the study.

Data collection

Data were collected from January 2015 to October 2015. After receiving official approval from the ethical committee, all the objectives and research plans were explained to the head nurses or key personnel in each setting and they were asked to cooperate in collecting data. These persons helped the researchers select and assess the participants. Patients who consented to participate were given full explanations and completed the study questionnaires. For participants who needed assistance as a result of health or visual problems, the principal investigator read the questionnaires directly to them and recorded their responses to each question.

Instruments

Three instruments were used for data collection: the Personal Information Questionnaire (PIQ), the Spiritual Needs Assessment (SNA), and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS), Thai version.

Section 1: The PIQ was developed by the principal investigator and includes items regarding sociodemographic data (age, gender, religion, marital status, educational level, family income, financial status, a method of payment for medical expenses, presence of a family caregiver, social support, and disease), medical information (type of disease, duration after diagnosis, type of treatment received, comorbid diseases, and Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) score), Buddhist practices (morality, concentration, and wisdom), religious beliefs, unfinished business, and happiness activities.

Section 2: The SNA was developed by Tewee Chaiyasen (Chaiyasen Reference Chaiyasen2009). The questionnaire covers the needs for meaning and goals in life, love and forgiveness, hope and encouragement, and faith and religion. The SNA consists of 23 items with a 4-point Likert-type scale (“not at all = 0” to “strongly need = 3”). The total score can range from 0 to 69. The cut points for the total score were as follows: a score in the range of 0–23 means low spiritual needs, a score in the range of 23.01–46 means moderate spiritual needs, and a score in the range of 46.01–69 means high spiritual needs.

Section 3: The SWBS (English version) was developed by Paloutzian and Ellison (Reference Paloutzian, Ellison, Peplau and Perlman1982) and was purchased from Life Advanced Inc. for use in our study. However, due to cultural differences between the western world and Thailand, Noipiang’s modified version of the SWBS was used in this study (Noipiang Reference Noipiang2002). Like the original version of the instrument, the modified SWBS consists of 20 items with 2 subscales with 10 items measuring religious well-being (RWB) and 10 measuring existential well-being (EWB). The SWB subscale has a 6-point Likert-type scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). Items with negative wordings are reverse scored. The scale yields 3 scores: a total score for SWB, a score for RWB, and a score for EWB. The 2 subscale scores can range from 10 to 60, while the SWB total score can range from 20 to 120 and is interpreted as the higher one’s SWB score is, the better one’s SWB is. The cut points for total SWB scores were as follows: a score in the range of 20–40 means low SWB, a score in the range of 41–99 means moderate SWB, and a score in the range of 100–120 means high SWB.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package (v.18.0.0). The data were cleaned and coded before being entered into the computer program, and a level of statistical significance of .05 was adopted. Descriptive statistics were conducted first to evaluate the sociodemographic data. The statistical analysis was then performed on the data as follows: (1) the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the spiritual needs among the different care settings, and (2) the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the differences in SWB and the levels of Buddhist practices among the care settings.

Results

The sample consisted of 170 patients with a terminal illness with a median age of 56.74 ± 15.61 years. The majority were male (51.2%), married (47.1%), and primary school graduates (44.1%). Most of them had an income of around 1,001–5,000 baht per month and perceived that they had sufficient income, but no savings (53.5%), and their health-care costs were covered by universal coverage (60%). Most of them had a family caregiver (95.9%) and received emotional support (91.2%), direct care (68.8%), informational support (56.5%), and financial support (42.4%). The most common terminal illnesses were cancer (68.2%) and AIDS (19.4%), followed by chronic kidney disease and liver disease (12.4%, combined). Hypertension (21.2%) was the most common comorbid disease, followed by diabetes mellitus (8.8%) and lung disease (8.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 170)

a One patient might have more than one selected.

Regarding the patients’ religion, the vast majority followed Buddhism (93.5%) and had religious perceptions and beliefs that birth and death are common for every human being (78.8%). Most of the participants have unfinished business (50%). The most common type of unfinished business that participants wanted to attend to was religious activities, such as making merit (15.9%), followed by activities related to their families (11.8%). The activities that made the participants feel happy were (1) religious activities, such as merit-making, prayer, and meditation (35.3%); (2) family activities (24.7%); and (3) recreational activities, such as watching movies, listening to music, or reading (17.1%).

Spiritual needs

Participants reported their overall spiritual needs to be moderate (mean score 45.37, SD 11.18), and the highest mean scores were as follows: (1) participating in the care plan (mean 2.59, SD .59), (2) being advised by the health-care team (mean 2.55, SD .71), (3) forgiving others (mean 2.54, SD .81), (4) asking for forgiveness (mean 2.51, SD .85), (5) praying for blessings (mean 2.49, SD .77), (6) praying not to suffer (mean 2.45, SD .79), (7) being close to family (mean 2.35, SD .9), and (8) having places for meditation (mean 2.28, SD .89).

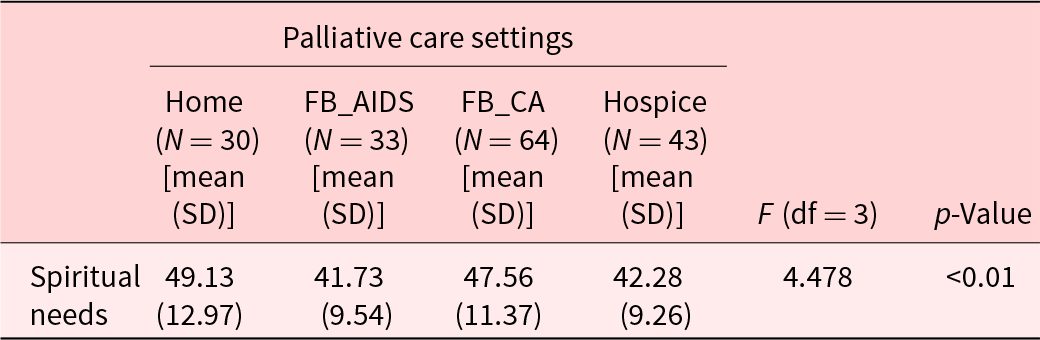

The comparison of the spiritual needs means scores among the 4 palliative care settings using ANOVA found significant differences in spiritual needs among participants in at least 2 of the 4 care settings (F = 4.478, p < .01) (Table 2). Using Tukey’s HSD statistics showed that the participants receiving care at Home had a significantly higher mean score than those receiving care through FB_AIDS and Hospice (p < .05).

Table 2. Comparison of mean scores for spiritual needs within the 4 palliative care settings using ANOVA (n = 170)

Spiritual well-being

The study’s findings also revealed that patients with terminal illness have a moderate level of SWB, with the mean scores for total SWB, RWB, and EWB being 98.80 (±14.98), 51.39 (±7.29), and 47.41 (±8.80), respectively.

Comparison of the palliative care setting’s mean scores using the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences in RWB (χ 2 = 71.555, p < .01), EWB (χ 2 = 75.597, p < .01), and SWB (χ 2 = 77.232, p < .01) (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean scores of spiritual well-being between palliative care settings by using Kruskal–Wallis test (n = 170)

Using multiple comparison tests, the participants receiving care at FB_CA had a significantly higher mean score for RWB, EWB, and SWB than those receiving care at FB_AIDS (p < .01), Hospice (p < .01), or Home (p < .01). The participants receiving care at Home had a significantly higher mean score for RWB than those receiving care at Hospice (p < .01) and a significantly higher mean score for SWB than those receiving care at FB_AIDS (p < .05) or Hospice (p < .05). The participants receiving care at FB_AIDS had a significantly lower mean score for EWB than those receiving care at Home (p < .01) or Hospice (p < .05).

Buddhist practices

The principles of Buddhist learning, or Buddhist practice, consist of (1) morality (Sīla), (2) concentration (Samādhi), and (3) wisdom (Paññā). The comparison of the frequency of Buddhist practice using the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences in the mean scores for RWB, EWB, and SWB (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of spiritual well-being by the frequency of Buddhist practice using the Kruskal–Wallis test (n = 170)

The multiple comparison test revealed that the participants who practiced morality regularly had significantly higher mean scores for RWB, EWB, and SWB than those who practiced occasionally (p < .01, p < .01, p < .01) or who rarely or never practiced (p < .01, p < .01, p < .01).

The participants who practiced concentration regularly had significantly higher mean scores for RWB, EWB, and SWB than those who practiced occasionally (p < .05, p > .05, p > .05) or who rarely or never practiced (p < .01, p < .05, p < .01).

The participants who practiced wisdom regularly had significantly higher mean scores for RWB, EWB, and SWB than those who practiced occasionally (p < .01, p < .05, p < .01) or who rarely or never practiced (p < .01, p < .01, p < .01).

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to compare the spiritual needs and SWB among patients with a terminal illness who were receiving care in 4 different palliative care settings and to investigate the associations between Buddhist practices and SWB. Participants’ scores revealed that their overall spiritual needs were moderate. The findings from this study showed that spiritual needs are related to holistic well-being, including the physical (e.g., without suffering), psychological (e.g., having help to share their feelings), social (e.g., family support), and spiritual dimensions (forgiving and being forgiven, places for meditation) (Mesquita et al. Reference Mesquita, Chaves and Barros2017). Another study found that the most frequently expressed spiritual needs were a feeling of attachment to family (90.7%), becoming more involved in family life (83.1%), living in a quiet and peaceful place (80.1%), and receiving more family support (74.3%) (Riklikienė et al. Reference Riklikienė, Tomkevičiūtė and Spirgienė2020). This is also consistent with the results of this study, which found that the participants receiving care at Home had a significantly higher mean score than those in the other settings. The explanation for this could be that at home patients are closer to their families, with the patients and their families living together in their home, enabling them to be sources of strength and support for each other. These activities make the patients and their families feel more comfortable and let go of feelings of suffering because the patients realize that they are not alone. Supportive relationships have been associated with numerous benefits for terminally ill patients, including increasing empowerment and hope, improving their overall well-being, facilitating positive relationships with family and friends, increasing confidence, and a fostering sense of control in relation to self, living with the illness, and interactions with each other (Ussher et al. Reference Ussher, Kirsten and Butow2006). The findings are congruent with a previous study that found that terminally ill patients with 3–4 family members had higher mean scores for spiritual needs than those with only 1–2 family members. Additionally, terminally ill patients who lived with family had higher mean scores of spiritual needs than those who lived alone (Wisesrith et al. Reference Wisesrith, Sukcharoen and Sripinkaew2021).

In this study, the highest mean scores for spiritual needs were found to be for participating in the care plan and being advised by the health-care team. This study affirms patients’ views that health-care provider–patient spiritual interactions are important. Health-care providers have an important role in supporting patients’ spiritual needs and can contribute to the spiritual care of their patients. Health personnel should have the competence and ability to care for the whole person: mind, body, and spirit (Riklikienė et al. Reference Riklikienė, Tomkevičiūtė and Spirgienė2020). The next most frequent spiritual need of the participants was found to be forgiving others and asking for forgiveness. Forgiving others is letting go of bad feelings and thoughts toward somebody who hurt you and replacing them with positive feelings and thoughts. Asking for forgiveness means that you seek forgiveness from someone you have hurt or made them feel bad. Forgiveness is important to the sense of peace and happiness. Forgiveness of others, or the self, can be important in regard to reducing guilt, facilitating the act of letting go, and bringing about inner peace. Forgiveness is quite important in palliative care settings and, therefore, forgiveness facilitation is critical in palliative care. The scoping review found that activities that have been implemented to provide forgiveness facilitation in palliative care settings have included active listening, life reviews, reminiscence, verbalization of family conflicts, the exploration of feelings of love and guilt, and reconciliation will (Silva et al. Reference Silva, Caldeira and Coelho2020). The findings from this study also correlate with a previous study (Riklikienė et al. Reference Riklikienė, Tomkevičiūtė and Spirgienė2020) that found that cancer patients place an exceptional amount of importance on Inner Peace and Giving and Forgiveness, while Religious and Existential needs score marginally lower.

This study found that patients with terminal illnesses had a moderate level of SWB, which is also associated with their overall spiritual needs being moderate as well. The mean scores for SWB, EWB, and RWB were 98.80 ± 14.98, 47.41 ± 8.80, 51.39 ± 7.29, respectively. The findings from this study were congruent with other studies. Pilger et al. (Reference Pilger, Santos and Lentsck2017) found that older adults undergoing hemodialysis attained moderate levels of SWB (mean = 93; SD = 13.52). The mean values attained on the EWB subscale (43.4; SD = 7.59) indicate moderate levels of satisfaction and life purpose among older adults. The RWB subscale displayed higher scores (50; SD = 7.54), which reflects a positive relationship with God (Pilger et al. Reference Pilger, Santos and Lentsck2017).

There were significant differences in SWB, EWB, and RWB among the participants from the 4 care settings. The participants receiving care at FB_CA had significantly higher mean scores for SWB, EWB, and RWB than those who were receiving care at FB_AIDS, Hospice, or Home, which may have been due to the activities and environment that existed in the FB_CA. Having the opportunities to have discussions, practice cultural/spiritual beliefs, and being encouraged to utilize ritual ceremonies, chanting, folk medicines, and traditional therapies may have provided meaning and purpose to them regarding their lives. Moreover, religious ceremonies are organized to cultivate faith and encourage patients to fight the illness. In the confession process, the patients wrote a letter about something they had done wrong and asked for forgiveness, which can have various positive effects, including forgiveness, renewal, new understanding, correcting personal faults, joy, peace, and empowerment (Murray-Swank et al. Reference Murray-Swank, McConnell and Pargament2007).

Moreover, there was a significant difference in SWB based on the frequency of Buddhist practice. Participants engaging in Buddhist practices more frequently had significantly higher mean scores for SWB. The findings from this study align with other studies. Rattanil and Kespichayawattana (Reference Rattanil and Kespichayawattana2016) found that Buddhist spiritual care could increase SWB among elderly patients with terminal cancer. Chimluang et al. (Reference Chimluang, Thanasilp and Akkayagorn2017) found that basic Buddhist principles could improve the religious dimension and the overall SWB, of patients with terminal cancer (Chimluang et al. Reference Chimluang, Thanasilp and Akkayagorn2017).

These findings were congruent with Get-Kong et al. (2010), who studied patients with advanced cancer. Spiritual, religious, and cultural beliefs and practices play a significant role in the lives of patients who are seriously ill and dying. In addition to providing an ethical foundation for clinical decision-making, spiritual and religious traditions provide a conceptual framework for understanding the human experience of death and dying and the meaning of illness and suffering (Daaleman and VandeCreek Reference Daaleman and VandeCreek2000). Making merit means doing good things, which was the Thai belief based on Buddhist doctrines. They strongly believe that regularly making and gaining merit would bring them happiness, a peaceful life, and other good things. Gaining merit will strengthen them to overcome any obstacles or misfortunes and help them to go to heaven, or a peaceful place, after their death (Manowongsa Reference Manowongsa2003). Meditation is also a form of religious practice; it can be viewed as another form of relaxation or visualization technique. Its aim is to calm down the mind and body. Concentrating on their breathing may be another way into this peaceful state (Brewer and Penson Reference Brewer, Penson, Penson and Fisher2002). Mindfulness is a meditation practice that involves being aware of whatever is happening in our body and mind accompanied by equanimity, freeing of attachment to what is pleasant, and aversion to what is unpleasant. Strong familiarity with this practice gives one the ability to cope with pain and discomfort, keep the mind free from disturbing emotions, and remain peaceful while dying (Khadro, Reference Khadro2003). In this study, most of the participants are Buddhists, so teachings of the Buddha of Buddhist principles and practices may be influencing the participants’ SWB too.

Conclusions

The findings of this study provide implications for nursing practice, policy, and further studies among patients with terminal illnesses. Various palliative care models exist in Thailand within various care settings, such as Home, faith-based organizations, and cancer center hospices. Each setting aims at improving QOL and SWB, so they provide palliative care based on objectives and the available resource. The results of this study found that the participants receiving care in a community hospital/home-based care setting had a significantly higher mean score of spiritual needs than those in other settings. Policy makers should utilize APNs to strengthen palliative care in community hospital/home-based care settings so that patients can receive care at home with their families if their conditions allow. The participants receiving care at the faith-based organization had significantly higher SWB than those in other settings. Moreover, participants engaging in Buddhist practices more frequently had significantly higher SWB. Thus, it is recommended that religious strategies should be emphasized and integrated in palliative care.

A cross-sectional study, by its very nature, is limited by not being able to capture patient changes over time for each variable. This study was conducted among patients with a terminal illness in 4 specific settings, thus, generalization to other terminal illness patients in other settings is limited. Therefore, there is a need to design a study using random sampling to recruit participants representing each setting and level of care to increase generalizability. Future research should also include developing and evaluating an intervention program to meet the spiritual needs and promote the SWB of patients based upon the knowledge gained about Buddhist practices. Additionally, a qualitative study to examine the human responses to terminal illness and care needs, among both advanced cancer patients and their families, also needs to be conducted.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University. We thank all of the participating patients for taking part in the study. This study was supported by Mahidol University, Thailand (grant number: DD-MHSA10).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.