Introduction

The Convention on Biological Diversity highlights the need for capacity development in its redrafting of strategy post-2020. One priority is to understand better how staff capacity inputs influence outcomes (e.g. ecological, social and organizational outcomes) to guide future policy (Bacon et al., Reference Bacon, Gannon, Stephen, Seyoum-Edjigu, Schmidt and Lang2019). To date, research addressing this has predominantly focused on protected areas, where some studies have identified staff capacity as a critical predictor of positive conservation impacts (e.g. Geldmann et al., Reference Geldmann, Coad, Barnes, Craigie, Woodley and Balmford2018), whereas another study highlights contextual influences (e.g. law enforcement, corruption, land title issues) as predictors of conservation success (Schleicher et al., Reference Schleicher, Peres and Leader-Williams2019).

Capacity, whether individual or organizational, varies according to context, and so is more usefully considered over time. Capacity development is defined as the intentional process whereby individuals, organizations or society build and maintain capacity over time (Simister & Smith, Reference Simister and Smith2010), and can be considered an umbrella term that includes both organizational and individual development (Lusthaus et al., Reference Lusthaus, Adrien and Perstinger1999). Acknowledging that capacity development may involve many participants and that capacity includes more than an employees' knowledge and skills (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Appleton, Ricci, Valverde, Reynolds, Worboys, Lockwood, Kothari, Feary and Pulsford2015), our study focused on individual capacity development, in particular the development of conservation professionals (not including pre-entry education). As in the education sector (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017), we used the term professional development to denote the active process of growth and development an individual undertakes in their professional life, across their entire career, including a range of approaches, activities and interventions, as well as the surrounding context and available resources that support this process. It is important to distinguish between professional development and professional learning. Professional learning refers to outcomes (what is learnt, how learning is applied and the establishment of new behaviour) whereas professional development refers specifically to the process that prompts such changes (Killion, Reference Killion2013).

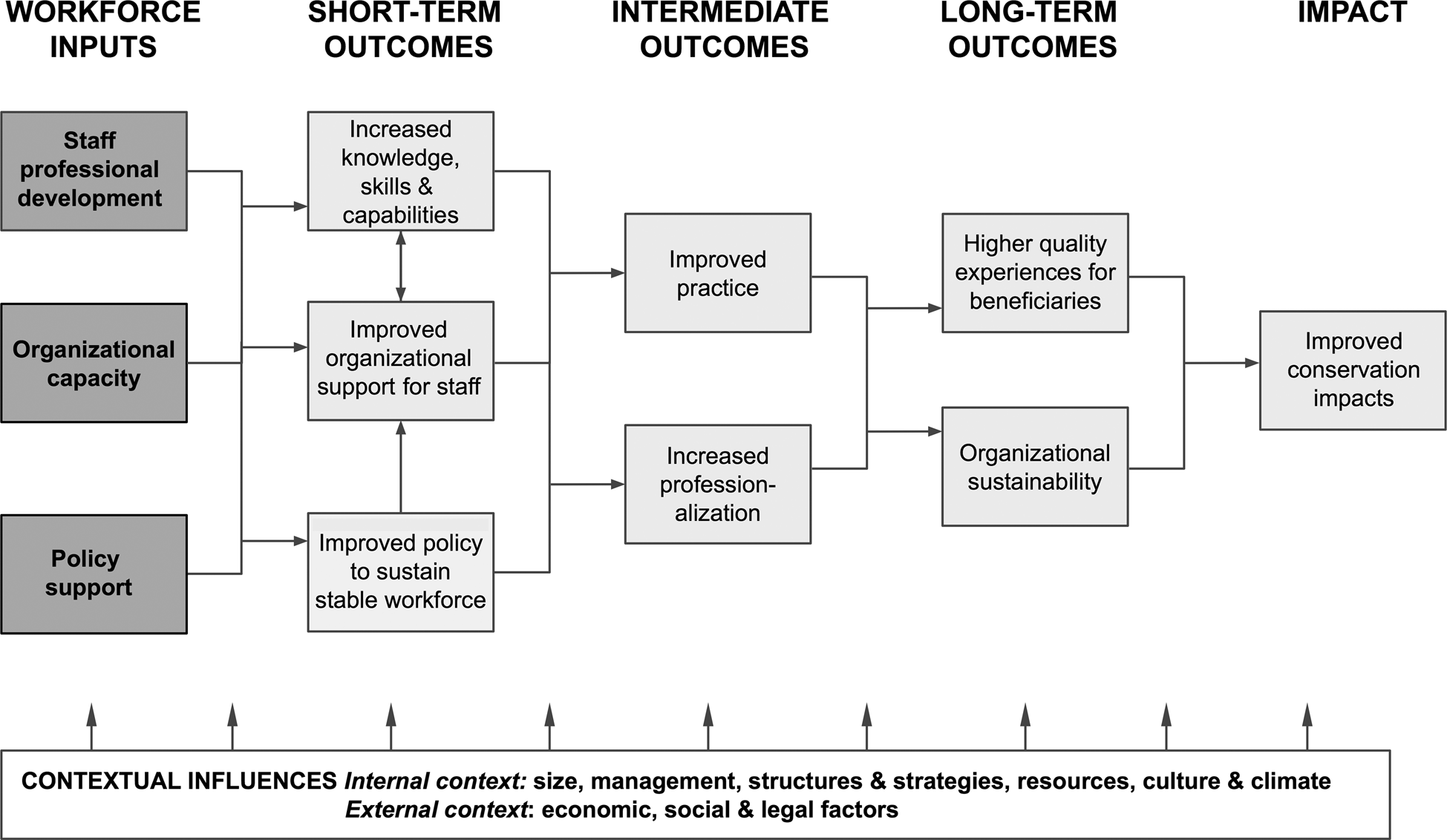

Other than wider evaluations of capacity development approaches (Sterling et al., Reference Sterling, Sigouin, Betley, Zavaleta Cheek, Solomon and Landrigan2021), as far as we are aware, to date, there have been no specific systematic reviews of professional development in conservation. Attempts to link professional development directly to conservation impact risk oversimplification, because there are many steps influenced by contextual factors, and conservation success may not be attributed to a single professional development initiative. Evidence of outcomes of professional development in conservation is scarce, but other sectors offer insights. Research in international development reveals that the further removed an impact is from the professional development intervention (e.g. organizational, beneficiary and/or biodiversity level), the more challenging is its attribution to that intervention (James, Reference James2009). Figure 1 illustrates four levels of professional development evaluation, drawing upon findings in education (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Klein, Little, Lopez, Rothert, Kreider and Bouffard2006) and training (Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick1996). The first level of measuring change is assessing the quality of intervention (short-term outcomes), followed by internal organizational changes (level 2: medium-term outcomes), external changes for beneficiaries (level 3: long-term outcomes) and external changes for biodiversity (level 4: impact).

Fig. 1 Conservation capacity model, adapted from a model for education (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Klein, Little, Lopez, Rothert, Kreider and Bouffard2006). Inputs, outcomes and impact are not all-encompassing and are provided here as examples of capacity development in conservation. Beneficiaries are recipients of improved conservation practice and may, for example, include landowners such as communities, governments and private companies.

Professional development needs in conservation

Studies of conservation capacity needs include evaluation of job advertisements, graduate programmes and capacity building initiatives, and perceptions of conservation professionals (Blickley et al., Reference Blickley, Deiner, Garbach, Lacher, Meek and Porensky2013; Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Barlow, Boddam-Whetham and Robinson2016; Parsons & MacPherson, Reference Parsons and MacPherson2016; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Gora and Alonso2017; Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Ryan and Wyborn2018; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Creasey, Skeats, Coverdale and Barlow2018), collectively highlighting gaps in non-technical skills and knowledge (interpersonal skills, communication, project management, interdisciplinary skills, strategic thinking, problem solving). A disconnect has been observed between formal pre-professional education received and the competences (i.e. knowledge, skills, abilities and related characteristics) needed for complex demands in situations encountered in conservation practice (Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Gora and Alonso2017). These competence requirements also vary by employer type (Blickley et al., Reference Blickley, Deiner, Garbach, Lacher, Meek and Porensky2013), geographical location of employment, and the location of the professional development provision (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Barlow, Boddam-Whetham and Robinson2016; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Gora and Alonso2017; Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Ryan and Wyborn2018). Professional development opportunities are therefore important for attracting and retaining staff (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2012) and have been positively associated with motivation, engagement and job satisfaction (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Kinnie, Hutchinson, Rayton and Swart2003). Many factors come into play when seeking relevant competences, and needs change over time as a result of socio-economic and technological developments, altering the relevance of existing competences. Standardization of competences remains less common in conservation compared to disciplines such as healthcare and law, making it challenging to evaluate professional development initiatives and the skill levels of individuals, potentially affecting the work and career progression of conservationists (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Barlow, Boddam-Whetham and Robinson2016). Interest in standardization is now growing, however, as illustrated by the Global Register of Competences for Protected Area Practitioners (Appleton, Reference Appleton2016) and the Global Register of Competences for Threatened Species Recovery (Maggs et al., Reference Maggs, Appleton, Long and Young2021).

Despite efforts to codify competences for conservation professionals, few studies have examined the conditions (e.g. content, format, contextual factors) required for professional development to yield positive effects on individual capacity and work performance, here called effective professional development. Our study addresses this. We defined a conservation professional as an individual who is paid or receives compensation in exchange for work supporting nature conservation goals. The process of professional development and learning outcomes is largely dependent on the behaviour of professionals, such as participating in professional development and applying newly acquired competences (Brekelmans et al., Reference Brekelmans, Maassen, Poell, Weststrate and Geurdes2016). The availability of resources and opportunities also influences whether new behaviour will occur (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Kinnie, Hutchinson, Rayton and Swart2003). We explore professional development across a variety of contexts, rather than following a case-study approach examining specific resources or opportunities, so we do not examine the perspectives of conservation organizations, and organization types were therefore not relevant to the scope of this study. Based on our research results, we were nevertheless able to make recommendations for how organizations could support employees in optimizing their professional development and learning outcomes.

We used semi-structured interviews with conservation professionals to explore professional development needs and provision by looking beyond learning content. To achieve this, we adopted a three-dimensional definition of work performance from other sectors (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans2014) that separates task performance, contextual performance and adaptive performance. Task performance is the competence where an individual performs core technical tasks central to their job (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, McHenry and Wise1990). Contextual performance involves competences addressing the psychological, social and organizational environment (Motowidlo & Van Scotter, Reference Motowidlo and Van Scotter1994). Adaptive performance is the ability to adjust to changes in work roles or work environment (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Neal and Parker2007). Our findings are intended to help conservation organizations and donors assess the quality of professional development provision, and to help professionals consider the quality of development they undertake. By including insights from other disciplines, such as education and healthcare, we aim to inform approaches to capacity development in global conservation.

Methods

Participants and interview guide

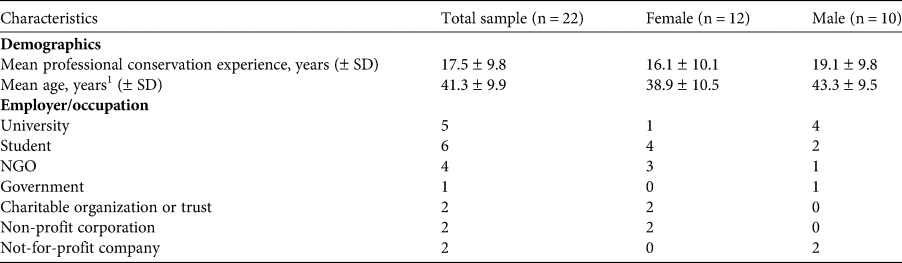

We used a qualitative research methodology as this was an exploratory study, with limited prior empirical evidence, so that we could generate propositions for future research (Newing, Reference Newing2011). We chose convenience sampling (Newing, Reference Newing2011), recruiting participants from three sources: (1) the University of Kent, UK, (2) attendees at an international conference of conservation professionals (University of Pune, India, 18–21 March 2017), and (3) our professional networks, thereby drawing people from a range of ages, roles and settings. All 22 respondents had professional experience working in countries with high biodiversity where capacity and access to resources are limited (in Africa, Latin America and developing regions in Asia), and were interviewed by TACL (Table 1). The sample size was adequate to identify meta-themes across different sites and to reach saturation; i.e. when new information results in little to no change to the codebook (Hagaman & Wutich, Reference Hagaman and Wutich2017). Prior to interviews, respondents were informed by e-mail of the research aims, and assured anonymity, confidentiality and freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. Interviews were conducted during March–June 2017 at a location convenient to the interviewee, with no non-participants except for one interviewee whose colleague was present. The semi-structured interviews lasted an average of 74 minutes (range 30–130 minutes). Questions followed an interview guide (Supplementary Material 1) and a checklist developed by Tong et al. (Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007) to promote explicit and comprehensive reporting in qualitative research (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the 22 conservation professionals, of 12 nationalities, participating in semi-structured interviews in 2017.

1 Based on eight female and 10 male professionals.

Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded in NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018) using keywords to categorize positive and negative perceptions and conceptual links, so that we could identify patterns and themes. We followed Braun & Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) thematic analysis and used both the inductive development of codes as well as a deductive approach to identify factors purported to influence professional development and learning outcomes (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Curry and Devers2007). For the deductive approach, we used various start lists from previous research in other sectors (e.g. Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017). Themes were identified, refined and/or expanded through comparison of data to identify theoretical saturation (Hagaman & Wutich, Reference Hagaman and Wutich2017). During transcription, participants were assigned ID numbers, and these are used hereinafter.

Results

All interviewees had recent (< 6 months before interview) experience of employed professional work in conservation. Eleven of the 22 participants were professionals in conservation roles at the time of interview. University-based participants included two senior lecturers, two lecturers, one postdoctoral researcher, one doctoral student and five MSc students (Table 1).

Characteristics of effective professional development

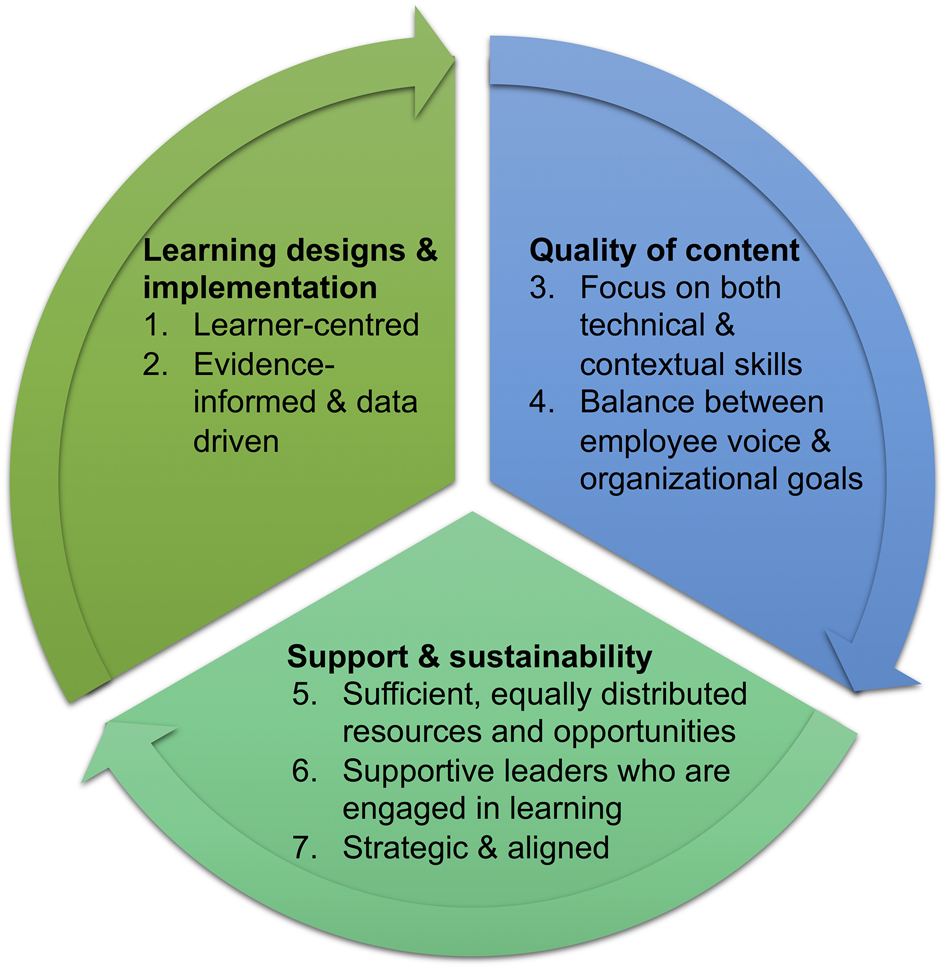

We identified seven components and three higher-order themes of professional development (Tables 2, 3 & 4), and used these to form an effectiveness framework for professional development; i.e. a system of key components that can be used to plan or decide on professional development (Fig. 2). All interviewees shared experiences covering at least one identified component; 86% (19/22) of respondents reported experiences in four or more components.

Fig. 2 Effectiveness framework for professional development, adapted from a framework for education (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017). This framework comprises three higher-order themes and seven key components (Tables 2, 3 & 4), indicating how higher-level components encompass and set prerequisites for effective professional development. This framework was derived from interviews with 22 conservation professionals.

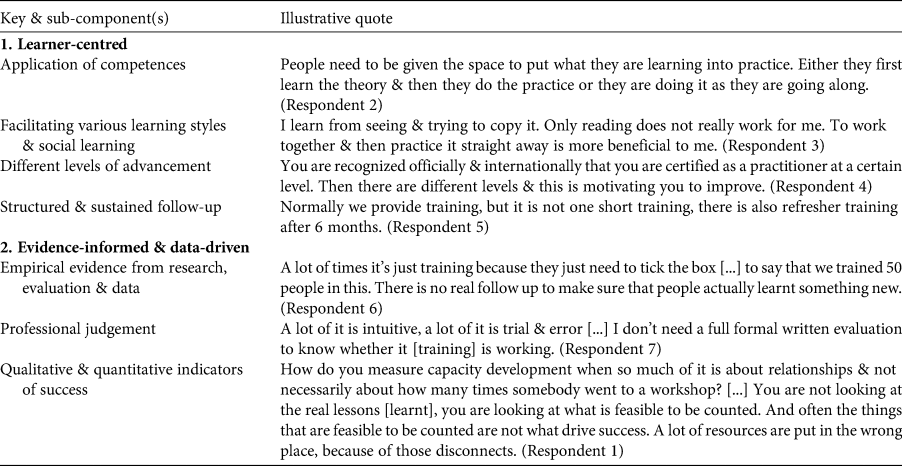

Table 2 Quotes from interviews with 22 conservation professionals during March–June 2017, illustrating key components 1 and 2, and their sub-components, of effective professional development related to learning design and implementation.

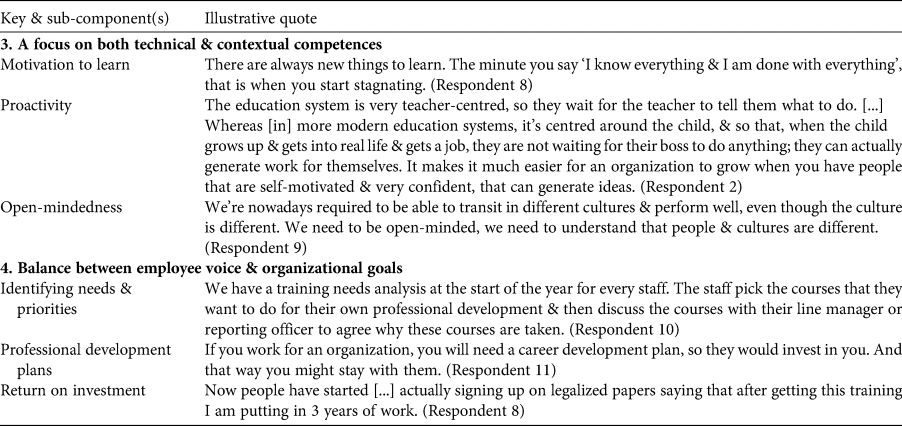

Table 3 Quotes from interviews with 22 conservation professionals during March–June 2017, illustrating key components 3 and 4, and their sub-components, of effective professional development related to quality of content.

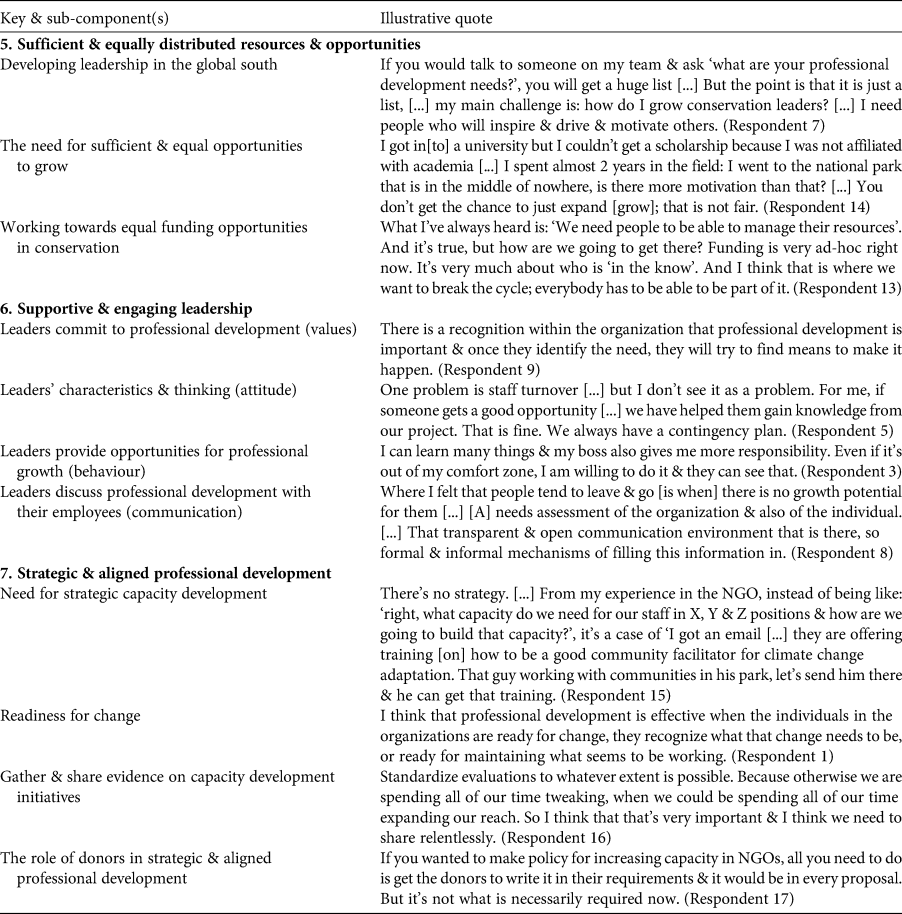

Table 4 Quotes from interviews with 22 conservation professionals, during March–June 2017, illustrating key components 5–7, and their sub-components, of effective professional development related to support and sustainability.

1. Learner-centred

This component comprised learner-centred descriptions of effective professional development reflecting adult learning theories, including experiential learning (i.e. learning from doing), and direct application of learning to work practice (Table 2). Some respondents highlighted the role of supervisory coaching and support to integrate newly acquired competences, whereas others mentioned learning with peers. Most interviewees described social learning experiences in organizations or wider professional networks. Some respondents stressed that structured and sustained follow-up after the development intervention (e.g. workshop) improves the effectiveness of learning.

2. Evidence-informed and data-driven

Few people reported evidence-based learning initiatives and few initiatives were prompted by data. Professional expertise and judgement were mentioned as important when assessing people's effectiveness (Table 2) but performance analyses at employee and/or organizational level were rarely reported. Respondent 1 mentioned that a range of indicators of conservation and professionalization outcomes is important, including quality and quantity. A starting point for developing qualitative indicators, according to this respondent, is to explore how knowledge exchange is influenced by context (e.g. national culture, organizational norms).

3. A focus on both technical and contextual competences

Most comments addressed non-technical activities, termed contextual competences (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans2014), such as communication and interpersonal skills (Supplementary Table 2). Several respondents emphasized that a professional has to maintain up-to-date skills and knowledge, known as adaptive competences (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans2014). Motivation to learn, proactivity and open-mindedness (to new information and the viewpoints of others) were perceived to enhance the ability to learn (Table 3).

4. Balance between employee voice and organizational goals

This component relates to development that balances both the needs of employees and organizational goals (Table 3). A skill-gap analysis was said to help identify discrepancies between employees' competences and those required for the job. Several respondents noted that development initiatives should address urgent and current needs. Some said that professional development plans could help balance career aspirations with organizational objectives, which people felt would enhance relationships with employers. Where an imbalance occurred, interviewees reported decreased motivation and increased intention to leave.

5. Sufficient and equally distributed resources and opportunities

This component places importance on sufficient and equally distributed opportunities and resources (e.g. funding) for professional development (Table 4). Respondent 12 noted that in 20 years of receiving international funding for conservation in their country, none was invested in building relevant expertise in-country, resulting in significant project delays when external experts could not enter because of natural disasters and political difficulties. Interviewees were supportive of needs-based approaches, yet the experience of three professional development providers suggested that, when asking employees to list their needs, these lists tended to be long and undeliverable. Instead, they suggested that staff are helped to develop independence in building their own capacity, including conservation leadership and fundraising capability, especially in biodiversity-rich countries with limited resources (Table 4).

6. Supportive and engaged leadership

The roles of leaders in facilitating a learning culture was highlighted, with an emphasis on leaders' supportiveness and engagement in learning. Interviewees mentioned that leaders should actively value professional development; e.g. by providing development to staff and communicating openly about development opportunities and decisions (Table 4). Five respondents provided a leaders' perspective, commenting that professional development is never wasted (Respondents 7 and 13), even if there is staff attrition (Respondent 8). Contingency plans are crucial in addressing staff turnover (Respondent 5), and Respondent 10 highlighted motivational approaches to prevent loss of staff. The resourcefulness and flexibility of leaders were important in creating cost-efficient development opportunities and to stabilize organizational capacity, such as attracting retired professionals as advisors.

7. Strategic and aligned professional development

This component concerned strategic capacity development aligning individual, organizational and wider interests (e.g. regional, sectoral). Overall, respondents noted that priorities for learning were driven by external funding rather than organizational strategies (Table 4). Where capacity development strategies were present, these were generally not integrated in the overarching strategic processes of organizations, and donor interests influenced implementation. Some participants noted the importance of individual and organizational readiness to change (Table 4). For example, Respondent 8 observed a conservation organization sending staff for external training, but afterwards giving people the same work and no career progression, which impeded the organization's sustainability, and many of its programmes failed. Multiple interviewees recommended gathering evidence on effective capacity development and sharing this between organizations (Table 4).

Discussion

Our findings, based on the views of a sample of conservation professionals, reflect previous research in the education sector (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017), and suggest seven key components for effective professional development (Fig. 2). There is considerable overlap between components and therefore our discussion addresses three higher-order themes: learning designs and implementation, quality of content, and support and sustainability.

Learning designs and implementation

There are many approaches to professional development (e.g. training, mentoring) and no single approach will suit all individuals under all conditions. Our findings are congruent with constructivist theories (Mathieson, Reference Mathieson, Fry, Ketteridge and Marshall2015) and demonstrate that professional development interventions should be grounded in adult learning theory, learner-centred, tailored to learners' previous knowledge and experiences, suited to engage with participants' various learning styles, and focused on integration of newly acquired competences into work. Most respondents highlighted the importance of social learning experiences, reflecting both social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1971) and empirical evidence (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017; Kainer et al., Reference Kainer, López Binnqüist, Dain, Contreras Jaimes, Negreros Castillo and Gonzalez Basulto2019). The success of any method will depend on the competences being developed. Learning cycle theories and competence registers can offer guidance in the design of learning processes, including which activities and techniques develop specific competences (e.g. Gibb, Reference Gibb2002; Kainer et al., Reference Kainer, López Binnqüist, Dain, Contreras Jaimes, Negreros Castillo and Gonzalez Basulto2019).

Our study revealed that few reported professional development initiatives were evidence-informed, similar to findings in healthcare and education (Schostak et al., Reference Schostak, Davis, Hanson, Schostak, Brown and Driscoll2010; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Osmond-Johnson, Faubert and Hobbs-Johnson2017). Our findings suggest quantitative indicators of capacity development may obscure what drives success and poorly reflect the true complexity of practice (Schostak et al., Reference Schostak, Davis, Hanson, Schostak, Brown and Driscoll2010). Qualitative indicators of success, combined with quantitative measures (e.g. the most significant change approach; Davies & Dart, Reference Davies and Dart2005), may address this, especially for contextual and adaptive competences, which are harder to measure. Before implementation, a professional development initiative should have a clear purpose and rationale, in addition to measurable learning outcomes, progress indicators and a method of evaluation (Guskey, Reference Guskey2000). Evaluation should consider the time required to practise and integrate newly acquired competences on the job and for changes in the wider organization to occur (Kainer et al., Reference Kainer, López Binnqüist, Dain, Contreras Jaimes, Negreros Castillo and Gonzalez Basulto2019). Evaluations should include details of the pedagogical activities implemented and the theory that both pedagogy and outcomes were based upon, to measure professional development quality and to attribute any improvements (Payler et al., Reference Payler, Meyer and Humphris2008).

Quality of content

Conservation professionals need contextual skills (e.g. interpersonal and communication skills), as identified in this study and previous research (e.g. Blickley et al., Reference Blickley, Deiner, Garbach, Lacher, Meek and Porensky2013; Parsons & MacPherson, Reference Parsons and MacPherson2016). Continuous learning is important for organizations focused on innovation (Psarras, Reference Psarras2006), so it is unsurprising that interviewees indicated keeping knowledge up-to-date as a key skill. Characteristics supporting this ability were motivation to learn, open-mindedness (e.g. towards the viewpoints of others), and proactivity (i.e. initiating change). These findings align with research in healthcare: increased motivation to learn encouraged nurses' participation in professional development (Brekelmans et al., Reference Brekelmans, Maassen, Poell, Weststrate and Geurdes2016). Open-mindedness facilitates work across science, policy and practice boundaries, an identified capacity gap within conservation (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Ryan and Wyborn2018). Van Woerkom & Meyers (Reference van Woerkom and Meyers2018) found self-efficacy to be a prerequisite for engaging in personal growth activities; people's belief in their abilities to master challenges and achieve desirable outcomes was followed by their proactivity towards personal growth. We recommend measurement of self-efficacy in future research on professional development.

Adaptivity is imperative in contexts of uncertainty or when not all roles can be formalized (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Neal and Parker2007). Our findings underline the importance of including contextual and adaptive competences (Supplementary Table 2), alongside technical/task competences, in any conservation competence register or professional development initiative. Researchers in other disciplines have already recognized that all three performance dimensions (task, contextual and adaptive) independently influence an employee's value for the organization (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Neal and Parker2007). The work performance definition adopted in our study offers a way for conservation organizations to integrate developmental behaviours to influence outcomes on an individual, organizational, and societal level. Additionally, a definition such as this can compare capability of individuals across a variety of roles and situations.

Our results indicate that a combination of organization-directed and self-directed professional development is required to balance career aspirations with organizational goals. Learners are better able to direct their growth by participating in the design of relevant learning processes (Calvert, Reference Calvert2016), thereby increasing their motivation to participate. Several tools were suggested by some of our interviewees, such as professional development plans, return-on-investment contracts, and needs assessments. However, needs assessments must identify underlying problems at work and barriers to wider sharing of learning, or there is a risk the approach will generate a list of wishes instead of needs (Guskey, Reference Guskey2000). Collectively, our findings highlight another priority area for professionals: building agency in one's own learning, namely the capacity to effectively direct one's professional growth and enable growth in others (Calvert, Reference Calvert2016).

Support and sustainability

The majority of interviewees reported professional development occurring sporadically, mostly because of limited funding, and some suggested that development follows external agendas such as donor requirements. Similarly, Nielsen (Reference Nielsen2012, p. 302) reported that in 832 protected area assessments in a total of 24 countries, training was ‘haphazard, ad hoc and inappropriate to the needs of the staff’. Professional development that is externally driven and top-down may merely address fashionable topics (Guskey, Reference Guskey2000), and so people may not acquire competence and expertise needed to solve complex challenges. Countries with high biodiversity and limited resources (e.g. lack of information and human capacity) are in many cases the countries most underfunded for conservation work (Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Mooers, Miller, Nibbelink, Redding and Kuhn2013). It is unsurprising that our respondents, all of whom had worked in biodiversity-rich yet resource-poor countries, reported unequal opportunities for professional development, and our findings suggest this decreased both morale and staff retention, congruent with previous research (Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2012). Our interviewees reported greater satisfaction and engagement at work when they felt their employers invested in them, mirroring findings for other sectors (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Kinnie, Hutchinson, Rayton and Swart2003). Leaders hold significant power over resource and opportunity allocation; so clear communication and decision-making can influence perceptions of fairness. Leaders have important roles in promoting a learning culture, and should commit to the development of all who affect conservation outcomes, including staff, communities, and external beneficiaries, thereby promoting engagement, staff retention and fruitful partnerships (Psarras, Reference Psarras2006). Successful alignment of capacity development requires stakeholder buy-in, as well as fitting programmes within wider, country-specific workforce strategies, including long-term (i.e. > 5 years) support (Aring & DePietro-Jurand, Reference Aring and DePietro-Jurand2012). Sectoral leaders (e.g. donors) can demonstrate how they value learning and improvement by prioritizing issues related to learning, enabling participation and co-design of professional development (Marsick & Watkins, Reference Marsick and Watkins2003), and providing both consistent funding and time. They can also provide sector-wide coordination of knowledge exchange, evaluation and policy development (Aring & DePietro-Jurand, Reference Aring and DePietro-Jurand2012).

One definition of successful professional development that emerged from our study is knowing how a learning opportunity can help improve conservation practice and how this change fits into the wider environment, whether organizationally, or across society, geographical area or sector. Guskey (Reference Guskey2000) suggested the effectiveness of professional development initiatives should be measured against two criteria: quality and value. The quality of an initiative is measured against its intended goal; e.g. learning objectives (inputs, Fig. 1). The value of an initiative is determined from fulfilment of needs; e.g. the needs of an individual professional, delivery of the conservation organization's mission or contribution to the public good (outcomes and impact, Fig. 1). Quality and value should be considered in selection and evaluation of professional development initiatives.

The active process of growth and development of a conservation professional, as a set of behaviours, largely depends on an individual's beliefs (e.g. attitudes, values and norms), self-perception of their abilities, intention to perform a certain behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckmann1985), and perceptions of their work environment (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Kinnie, Hutchinson, Rayton and Swart2003). In this study, we focused solely on the individual level; i.e. data concerning the individual's perspectives of professional development. The availability of resources and opportunities to support professional development also influences whether this process delivers valued learning outcomes. Future research could usefully include measures of organizational mechanisms, resources and opportunities.

Implications for conservation organizations

Our research provides guidance on designing professional development initiatives and assessing the quality of professional development in conservation. Our effectiveness framework for professional development includes recommendations covering planning, design, implementation and evaluation, going beyond common assessments that solely measure learner satisfaction. We recommend involving interested parties and advisers from the outset of a professional development initiative, to ensure a collaborative approach that is socially relevant and builds learner agency. We also conclude that more research is needed on the effects and causality of professional development on short-, medium- and long-term outcomes. Taking an interdisciplinary approach to this kind of research may help establish quantitative and qualitative evidence of transformed conservation practice, organizational sustainability, higher quality experiences for beneficiaries and improved conservation impacts. Internal factors for any conservation organization (e.g. management, resources, culture) and external contextual influences (e.g. economic, social and political factors) should be considered.

Learning and working are interconnected. Organizations involved in conservation activities will not improve outcomes for biodiversity unless employees grow professionally, improve practice, and build organizational memory and expertise. This study identified organizational and systemic changes required to accommodate and facilitate these individual improvements. Although there is no single approach to creating effective professional development, we hope our framework serves as a timely contribution to the literature on capacity development.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for their willingness and openness in sharing their experiences.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, design, writing, revision: all authors; data collection, analysis and interpretation: TACL.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research was supported by a Vice Chancellor's Research Scholarship of the University of Kent, Canterbury, UK, and has been approved by the Research Ethics Advisory Group of the School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent (Ref no 0401617). This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards and by the British Sociological Association Statement of Ethical Practice 2017.