Introduction

There is a considerable body of literature on the impact of law enforcement efforts to reduce illegal activities, preserve wildlife abundance, and monitor and manage conservation areas (Leader-Williams et al., Reference Leader-Williams, Albon and Berry1990; Hilborn et al., Reference Hilborn, Arcese, Borner, Hando, Hopcraft and Loibooki2006; Critchlow et al., Reference Critchlow, Plumptre, Alidria, Nsubuga, Driciru and Rwetsiba2016). Until recently, relatively little was known about the perceptions and realities of front-line conservation staff, including rangers (also known as forest guards, scouts and game wardens, amongst others). This is surprising given the central role rangers have in collecting and documenting data, monitoring, and enforcing laws and regulations. Moreover, as rangers are often the primary contact for local community members, they are effectively the personification of conservation efforts. By assessing the perceptions of front-line conservation staff, a better understanding of the human dimensions of conservation science (cf. Jacobson & Duff, Reference Jacobson and Duff1998) can be established, while facilitating and promoting interdisciplinary scholarship (cf. Adams, Reference Adams2007; Moreto, Reference Moreto2015, Reference Moreto2017).

Attention to rangers’ perspectives has increased since the 1990s, particularly among social scientists. Researchers have investigated variation in selection and training of wildlife law enforcement personnel (Warchol & Kapla, Reference Warchol and Kapla2012), roles and responsibilities (Shelley & Crow, Reference Shelley and Crow2009; Moreto & Matusiak, Reference Moreto and Matusiak2017), perceptions of danger (Forsyth & Forsyth, Reference Forsyth and Forsyth2009), discretion (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth1993; Carter, Reference Carter2006), job stress and job satisfaction (Eliason, Reference Eliason2006; Oliver & Meier, Reference Oliver and Meier2006; Moreto, Reference Moreto2016; Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Lemieux and Nobles2016), community relations (Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Brunson and Braga2017), and corruption and misconduct (Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Brunson and Braga2015). Most of these studies are primarily descriptive, and all were conducted in the USA or Africa. No large-scale study has previously been conducted on rangers working in Asian conservation areas.

Another neglected element is the prevalence and consequences of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation types, and intergenerational linkages. Broadly defined, intrinsic motivation refers to ‘doing an activity for its inherent satisfactions rather than for some separable consequences’ (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000, p. 56), whereas extrinsic or instrumental motivation occurs ‘whenever an activity is done in order to attain some separable outcome’ (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000, p. 60). We define intergenerational linkages as the connection amongst and between familial generations. Although research has shown that parents influence their children's attitudes, activity choices and occupational aspirations (e.g. Eccles et al., Reference Eccles Parsons, Adler and Kaczala1982; Jodl et al., Reference Jodl, Michael, Malanchuk, Eccles and Sameroff2001; Wong & Liu, Reference Wong and Liu2010), researchers have not systematically examined intergenerational linkages within the policing profession, and no studies have previously assessed this process among rangers. As a dimension of anticipatory (pre-employment) socialization (Stojkovic et al., Reference Stojkovic, Kalinich and Klofas2003), parental guidance, especially with respect to not endorsing a policing career, could play a major role in the recruitment of police personnel. Likewise, motivation type has been studied minimally within the policing literature (Brough & Frame, Reference Brough and Frame2004; Abdulla et al., Reference Abdulla, Djebarni and Mellahi2011; Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2013) but has not been extended to include rangers.

Here we examine the relationship between motivation type (intrinsic or extrinsic) and intergenerational job linkages (whether rangers want their children to enter the profession) among a sample of rangers in Asian conservation areas. With > 10,900 protected areas, covering 13.9% of terrestrial and 1.8% of marine and coastal areas, Asia is integral to global biodiversity (Juffe-Bignoli et al., Reference Juffe-Bignoli, Bhatt, Park, Eassom, Belle and Murti2014). To the best of our knowledge the current study is the first to assess the orientations of rangers working in Asia and is one of the most comprehensive studies conducted on rangers in general. We interpret our findings in light of their implications for improving rangers’ job commitment and desire to pass careers in conservation through the generations. Our recommendations will help countries and conservation area administrators understand what their front-line rangers need to remain committed to the profession.

Human resource management research has demonstrated the influence of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors on staff motivation. For instance, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation has been examined within the scope of prosocial motivation and occupational persistence, performance, productivity, and rewards (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Koestner and Ryan1999; Grant, Reference Grant2008). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation does not necessarily operate on a continuum; rather, intrinsic motivation can be influenced by extrinsic factors, including organizational and social rewards, and these factors can affect employee job satisfaction and task perception (Mottaz, Reference Mottaz1985; Amabile, Reference Amabile1993; Bénabou & Tirole, Reference Bénabou and Tirole2003). Individual and global factors may be affected differently by intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. For instance, Huang and Van de Vliert (Reference Huang and Van De Vliert2003) found that the relationship between extrinsic job characteristics and job satisfaction held uniformly across all 49 countries they studied, but intrinsic job characteristics were associated with job satisfaction only in developed nations.

The importance of motivation type has been acknowledged within the conservation science and police literatures; for example, the role of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in altering and guiding conservation behaviours and perceptions has been discussed and debated (De Young, Reference De Young1986, Reference De Young1993; Angermeier, Reference Angermeier2000; Sheldon & McGregor, Reference Sheldon and McGregor2000; Winter, Reference Winter2007; Justus et al., Reference Justus, Colyvan, Regan and Maguire2009; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Bruskotter and Nelson2015). Within the policing literature, research suggests that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are associated with police officers’ job satisfaction (Abdulla et al., Reference Abdulla, Djebarni and Mellahi2011), work engagement (Gillet et al., Reference Gillet, Huart, Colombat and Fouquereau2013), and willingness to change employer (Brough & Frame, Reference Brough and Frame2004; Schyns et al., Reference Schyns, Torka and Gössling2007, p. 661). Nevertheless, much remains to be understood about motivation type and, especially, how it could relate to the willingness of employees (in this case, wildlife rangers) to encourage their children to enter the profession.

Parents play an influential role in their children's attitudes, beliefs, self-perceptions, interests, and activity choices (e.g. Eccles Parsons et al., Reference Eccles Parsons, Adler and Kaczala1982), including their occupational aspirations (Bregman & Killen, Reference Bregman and Killen1999; Jodl et al., Reference Jodl, Michael, Malanchuk, Eccles and Sameroff2001; Wong & Liu, Reference Wong and Liu2010). Little is known, however, about the intergenerational linkages that may exist within the policing profession, or the factors that may make police officers want (or not want) their children to also become officers. Police culture is entwined with the socialization of police officers into the occupational role (Paoline & Terrill, Reference Paoline and Terrill2014); however, more attention has been focused on proximal forms (occupation-based) of socialization as opposed to distal types (personal-based). The few studies that have investigated this link within the policing literature suggest that having a parent or close relative socialize an individual to the policing profession appears to play some role in the pre-professional socialization and recruitment of law enforcement officers (Van Maanen, Reference Van Maanen1975; Crank, Reference Crank1998). However, these works have focused on the effects of socialization from the perspective of children of police officers rather than the parents’ perspective.

In his participant observational study of police pre-professional socialization in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, Conti (Reference Conti2006, p. 229) concluded, ‘For any recruit who is following something akin to a family tradition, those police relatives are likely to play an active role in his or her institutionalization. This can include everything from encouragement to expert advice.’ In a survey of 182 Chinese police cadets, Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Sun and Cretacci2009) found that the influence of parents was among the top motivations (3rd out of 19 choices) to join the police force. Phillips et al. (Reference Phillips, Sobol and Varano2010), using survey data collected from 70 police recruits in a training academy in New York, USA, reported that recruits entering their first day in the academy who had relatives in law enforcement held more favourable orientations toward aggressive patrol tactics and the need to assist citizens, and less favourable views of supervisor support and citizen cooperation compared to those newcomers who did not have relatives in the occupation. These studies, however, focused on what may have influenced serving officers, not whether they themselves would want their children to enter policing.

Our aim here is to examine motivational characteristics and intergenerational linkages of rangers working in Asian conservation areas. To the best of our knowledge no previous research has examined whether intrinsically or extrinsically motivated parents differ in their preferences for their children's occupational choices.

Firstly, we examine rangers’ perceptions of occupational factors that may motivate or demoralize them. Secondly, using logistic regression we examine potential intergenerational linkages within the ranger profession by assessing respondents’ perceptions of whether they want their children to also become rangers, and why or why not. Thirdly, we use χ 2 tests to analyse more closely how the dimensions of motivation relate to respondents’ stated reasons for not wanting their children to enter the occupation.

Methods

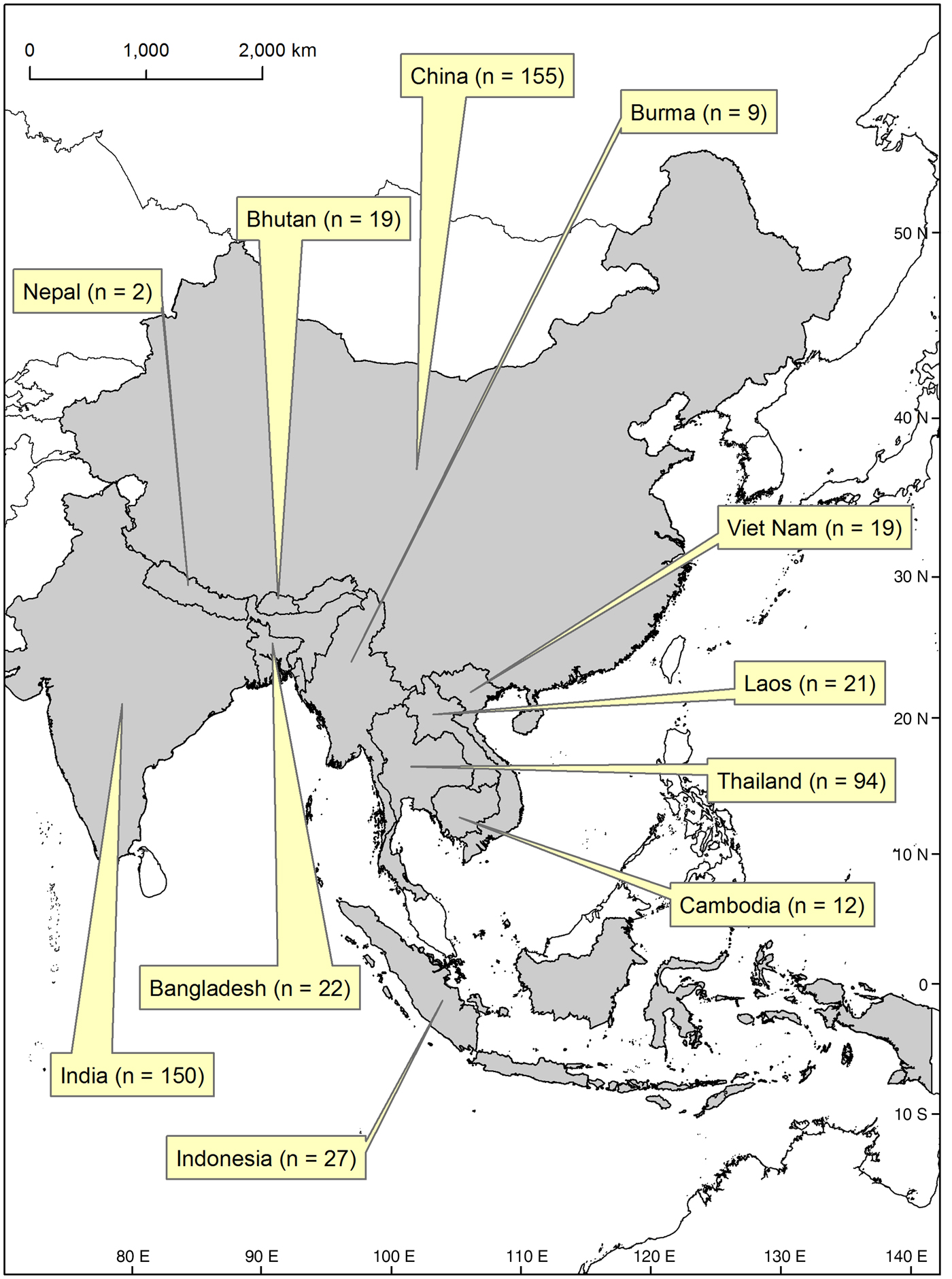

The data analysed are from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal, Thailand, and Viet Nam; Fig. 1). Site selection was based on accessibility and contacts in the field. Twenty-six are sites where WWF actively supports conservation efforts. These areas were chosen for ease of access and because surveying could be carried out during the course of regular operations. In countries and sites where WWF does not have direct access to front-line staff, we partnered with other conservation organizations (Wildlife Conservation Society; Karen Wildlife Conservation Initiative) and ranger associations. This was useful in obtaining approval from the local governments and conservation area authorities, while ensuring variation in the definition of front-line rangers.

Fig. 1 The 11 Asian countries (shaded) included in the study of occupational motivation and intergenerational linkages among rangers working in 39 conservation areas, with the number of respondents for each country, in parentheses.

Prior to the beginning of the fieldwork, personnel responsible for data collection met with the research team. These initial meetings ensured that methods were standardized across the study sites. Administration guidelines were also included with the survey to remind data collectors and respondents how to complete and submit the questionnaire. Data were collected during January–July 2015.

Questions were drafted by WWF in consultation with subject experts. The final survey instrument contained 10 questions, most of which had sub-parts, tapping into basic aspects of the occupation (e.g. working conditions, dangerous encounters with poachers or wildlife). To avoid hindering or obstructing the daily operations of the study sites, we utilized convenience sampling to access our study participants. Before completing the survey, respondents were informed of voluntariness and confidentiality, and were briefed on the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. The majority (> 80%) of surveys were administered in person and in private. Surveys were administered by WWF and other partners (mentioned above). Although the potential for undue influence from the involved organizations is possible, we believe that the respondents’ familiarity with data collectors themselves may have alleviated such concerns. We are confident that data collectors, who were known by respondents and had first-hand knowledge of the conservation areas, were more likely to garner trust and rapport and foster a comfortable and open environment for respondents compared to an external researcher. Additional responses were obtained from paper surveys submitted by mail, and e-mail. In total, we received responses from 530 study participants. This study was approved by the University of Central Florida Institutional Review Board (SBE-17-13145).

The dependent variable was the response to the survey question ‘Would you want your children to become rangers?’ This is a dichotomous variable; those who responded ‘yes’ were coded as 1, and those who responded ‘no’ were coded as 0. Respondents who were not parents could answer the question hypothetically. The sample was split almost evenly: 52% said they wanted their children to become rangers and 48% said they did not.

The primary predictive construct was respondents’ motivation for being wildlife rangers. To operationalize this, we used a variable from the survey that offered respondents nine possible reasons, representing five intrinsic and four extrinsic values. Respondents ranked the relative importance of each factor compared to the rest. As this variable was rank ordered, we could not treat it as continuous and instead had to recode it into categories for analysis. We divided respondents into three groups. Those whose top two rankings were both intrinsic were categorized as intrinsically motivated, those whose top two rankings were both extrinsic were categorized as extrinsically motivated, and the remainder were considered to have mixed motivations. We chose the top two as the cut-off point for each group to establish groupings for the extremes while also allowing for a mixed group.

The multivariate model includes several control variables derived from the survey. The first three capture rangers’ perceptions about facets of their job. Perceived danger is a summed index of respondents’ reports of having been attacked by poachers, threatened by poachers, or threatened by communities because of their work. We coded responses to each variable as yes = 1 and no = 0 and then summed these scores. The dichotomous variable training indicated whether respondents felt adequately trained for their job (yes = 1), and the dichotomous variable equipment indicated whether respondents felt they were provided with proper amenities (e.g. clothes, food, firearms and global positioning systems) to ensure their health and safety in the field (yes = 1). The remaining controls were for demographic characteristics. Age and years of experience were both ordinal (1–10), gender was represented as male (male = 1 and female = 0), and employment status was measured as permanent (1) or temporary. Rangers on permanent contracts are on payroll, have salaries, and are usually eligible for government benefits, whereas temporary rangers are on contract, work for daily wages, and receive few or no government benefits. The final variables included a series of dichotomous responses to follow-up questions posed after the initial question asking respondents whether or not they wanted their children to be rangers. Respondents were presented with a series of possible reasons for their decision. We examine respondents’ most commonly cited rationales for wanting, or not wanting, their children to be rangers, in terms of whether intrinsic or extrinsic considerations appear to factor more prominently in this decision.

We begin by presenting the percentage results of the motivation items that received the top two and bottom two rankings. This offers an overview of whether respondents seemed to be guided primarily by intrinsic motives, extrinsic ones, or a mixture of the two. We then enter a multivariate framework. As the dependent variable is binary, we use logistic regression to examine whether motivation type significantly predicts rangers wanting their children to go into the occupation, net of controls. Finally, we examine a series of χ 2 tests to examine in greater detail the relationship between rangers’ motivation and their reasons for wanting or not wanting their children to become rangers. All analyses were carried out using SPSS v. 22 (IBM, Armonk, USA).

Results

We first sought to understand aspects of the job that may contribute positively to rangers’ occupational satisfaction, by analysing the numbers and percentages of respondents who ranked each of the nine job aspects as their first or second choices (i.e. the things they liked most about the job) and as their eighth or ninth choices (i.e. the things they liked least). Thus, the top rankings indicate the aspects rangers strongly endorse as reasons for staying in the job, and the bottom rankings indicate the aspects of the job that are not as important to them.

The results for the top rankings are in Table 1. The response chosen most frequently as the main motivation to continue working as a ranger was having no other job option (47.4%), followed by good promotion prospects (24.3%) and liking the power and authority (23.6%). All top three responses are extrinsic, suggesting that rangers’ commitment to the job is influenced most strongly by instrumental factors within the control of protected area administrations.

Table 1 Aspects of their job that most motivated (extrinsically or intrinsically) rangers from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries (Fig. 1) to continue working as rangers, with the number and percentage of respondents who chose each option.

The bottom-ranked factors are in Table 2. Enjoying being close to nature was the least important factor (47.2%), followed by enjoying being a ranger (43.2%) and having good promotional prospects (22.1%). The first two are considered to be intrinsic motivations, whereas the third is extrinsic. Good promotion potential was within the top three for both positive (Table 1) and negative (Table 2) responses. We conclude from these results that although intrinsic aspects of the job matter, rangers’ motivation is driven primarily by extrinsic or instrumental concerns.

Table 2 Aspects of their job that least motivated (extrinsically or intrinsically) rangers from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries (Fig. 1) to continue working as rangers, with the number and percentage of respondents who chose each option.

Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the logistic regression to determine whether motivation type significantly predicts rangers’ desires for their children to enter this line of work are in Table 3. There was significant variation across categorized motivation types, with 27% of respondents categorized as intrinsically motivated, 39% extrinsically motivated, and 35% of mixed motivation.

Table 3 Descriptive statistics of survey participants (530 rangers from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries; Fig. 1).

For the regression we selected the mixed motivation category as the referent, to compare the two more polarized groups to the middle one. Listwise deletion resulted in a loss of only 8% of cases, so imputation was not used. The results are in Table 4. The model χ 2 was statistically significant. The percentage of cases correctly categorized increased from 50.9% in the baseline model to 63.9% in the fully specified model, a 26% proportional reduction in error ((49.1–36.1)/49.1 = 0.26). The model, therefore, is modestly useful in explaining respondents’ desires for their children to become rangers. Tests for influential values did not reveal any cases whose deletion would meaningfully improve model fit.

Table 4 Logistic regression examining the desire among rangers (n = 485) from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries (Fig. 1) for their children to become rangers. Mixed motivation is the referent category. Model χ 2 is significant (χ 2 (9) = 55.103**); −2LL = 617.083; Cox & Snell R 2 = 0.107; Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.143.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001

The regression results show that motivation type, as determined by extrinsic and intrinsic factors, remains significant even after controlling for other occupational attitudes and demographics. Extrinsic motivation in particular is important: this group had more than double the odds of wanting their children to be rangers (odds ratio (OR) = 2.258) compared to those with mixed motivations. Intrinsically motivated rangers, likewise, were more likely than their mixed-motivation counterparts to express a desire to see their children enter the occupation (OR = 1.794). The mean predicted probabilities were 0.52 for the intrinsic group, 0.60 for the extrinsic group and 0.39 for the mixed group.

Two control variables emerged as statistically significant. The odds of wishing for one's children to be rangers was more than double for those who believed they were adequately equipped for the job compared to those who felt equipment and food were lacking (OR = 2.468) and for those with a permanent job status as opposed to temporary employees (OR = 2.460). These are both consistent with extrinsic or instrumental concerns, further underscoring the centrality of the work environment to rangers’ job commitment.

Next, we examine the specific reasons why rangers do or do not want their children to enter the occupation (Table 5). The two sections on the survey offered respondents different sets of options, with the ‘reasons for wanting children to be rangers’ section reflecting both intrinsic and extrinsic rationales and the ‘reasons for not wanting children to be rangers’ options being extrinsic only. We used χ 2 tests to determine which group comparisons were statistically significant.

Table 5 Percentage of rangers (n = 485) from 39 conservation areas in 11 Asian countries (Fig. 1) who responded ‘yes’ to each reason for wanting (or not wanting) their children to become rangers.

1 Intrinsic

2 Extrinsic

3 All factors are extrinsic

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Intrinsically motivated rangers endorsed intrinsic reasons for wanting their children to be rangers, such as they want their children to serve nature (92%), protect wildlife and biodiversity (88%), and serve their country (78%), and that they themselves are proud to be rangers (78%). However, the intrinsic group also strongly endorsed a desire for power and authority (59%) and job security (56%) at rates far exceeding the other two groups. Similarly, those who were intrinsically motivated and did not want their children to be rangers expressed instrumental concerns, citing the low salary (80%), poor facilities (76%), absence of rewards for hard work (64%), and poor promotional opportunities (56%) far more often than the other two groups. It seems that both intrinsic and extrinsic considerations matter in determining rangers’ intergenerational job commitment. Extrinsically motivated rangers are the ones most likely to want their children to take on the job, and intrinsically motivated ones seem to rely most heavily on extrinsic or instrumental factors in deciding whether or not they want their children to join the occupation.

Discussion

This study contributes to the growing literature examining the human dimensions of front-line conservation efforts, while also expanding the policing and human resource literature. Our findings reveal variation in rangers’ motivations for doing the job, and in the relationship between motivation and wanting or not wanting their children to become rangers. This suggests that intergenerational linkages within the ranger occupation may be influenced by parental beliefs and perceptions. As a collective, rangers who wanted their children to become rangers chose intrinsic factors for their reasoning more so than extrinsic factors. Intrinsically motivated rangers were particularly enthusiastic about intrinsic reasons; however, they were also more likely than the other two groups to select extrinsic factors as well, and were considerably more likely to cite extrinsic characteristics as reasons for not wanting their children to enter the occupation.

Our results point to the importance of intrinsic factors in ranger occupational motivation, and mirror prior research showing the powerful impact that extrinsic factors have on intrinsic motivation (Mottaz, Reference Mottaz1985; Amabile, Reference Amabile1993; Deci et al., Reference Deci, Koestner and Ryan1999). In other words, although intrinsic aspects appear to be important for rangers, extrinsic features of the occupation also warrant attention (cf. Moreto, Reference Moreto2016; Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Lemieux and Nobles2016). Our findings contribute to the ongoing discussion about whether the intrinsic value of nature is sufficient to guide and justify conservation decision making or whether instrumental factors are more effective (cf. Justus et al., Reference Justus, Colyvan, Regan and Maguire2009; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Bruskotter and Nelson2015), particularly given how such perceptions appear to influence ground-level staff. In particular, our findings suggest extrinsic factors considerably influence even those rangers who have vested intrinsic interests in biodiversity and conservation. It cannot be simply assumed that front-line conservation personnel will be intrinsically driven or that such motivation will be unaffected by the challenges and realities of the occupation. Thus, understanding how physical, social and work-related constraints affect rangers’ orientations towards their occupation and conservation as a whole (cf. Heberlein, Reference Heberlein2012) is a worthwhile endeavour, as this may influence how they perceive and implement certain conservation initiatives (cf. Moreto et al., Reference Moreto, Lemieux and Nobles2016). Understanding how these factors may influence employee motivation can also shed light on other important facets, including organizational commitment (Crewson, Reference Crewson1997). Moreover, as occupational status (permanent compared to temporary) and perceptions regarding equipment were also found to be associated with rangers’ wanting their children to also become rangers, it is clear that the characteristics of the job, and not just conservation for its own sake, influence their outlook.

These findings have implications for governments and the local administrators of conservation areas seeking to hire and retain high-quality front-line staff. Governments and conservation area administrators should staff their ranger ranks with people who possess intrinsic desires to preserve natural habitats and personal commitments to conservation, but they must also provide those employees with adequate pay, equipment, and promotional opportunities. In terms of successful recruitment from the families from which rangers have already been hired, trained and, possibly, promoted, these would be worthwhile extrinsic investments. In the absence of instrumental reasons to remain loyal to the job, intrinsically motivated rangers may serve out their own careers but persuade their children to seek employment elsewhere. All of these factors highlight the importance of investigating ranger welfare and working conditions in more detail, and using results from such studies to influence local budget allocation, along with national and international policies to address the need to improve the support provided to rangers. Such investments would be likely to improve ranger motivation and virtuosity, as well as bolster the recruitment of the next generation of rangers.

In terms of the general policing literature, further study is warranted to examine whether our findings may be generalized to police officers. This is especially salient, in the USA for example, given the current reciprocal concerns of deteriorated police–community relations (President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 2015). If our findings may be generalized to local police, upper-level administrators would be wise to tailor their recruiting and hiring practices to bring in people with genuine investments in serving the public, and then provide a work environment that rewards their accomplishments.

This study is the first to examine ranger perceptions across multiple countries in Asia, but it is not without its limitations. Given the wide variation in the number of respondents per protected area and per country, we were not able to model protected area or country level characteristics in a multilevel framework. Additionally, the survey was relatively short and probably omitted variables and constructs relevant to a full understanding of rangers’ motivations and the factors they like most and least about the job. The data are also cross-sectional and it is possible that rangers’ perceptions change throughout the course of their careers. Future research should examine rangers’ perceptions at various time periods of their career (e.g. a cohort model) to gain a more complete understanding of the topic. Moreover, the sites chosen for this study had financial or technical assistance from outside bodies (e.g. WWF). As such, the opinions presented here may not necessarily reflect those of rangers working in protected areas without such assistance. Women constituted a small minority of the sample (reflecting their extreme under-representation in the occupation), which precluded an analysis of whether motivation or desire for children to become rangers varied according to gender. All of these considerations offer avenues for future research on this topic.

It is possible that various forms of extrinsic motivation (Gagné & Deci, Reference Gagné and Deci2005) may have different effects on rangers’ intrinsic motivation. Another area of future study could be the potential applicability of both self-determination and cognitive evaluation theories (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Gagné & Deci, Reference Gagné and Deci2005). According to these theories, both forms of motivation, particularly intrinsic, are influenced directly by the surrounding social environment, and different contexts will result in different types of motivation. Our findings suggest that this may have been the case for some rangers in our study. Moreover, future studies should examine how both proximal (e.g. promotion) and distal (e.g. parental socialization) forms of extrinsic motivation within the scope of self-determination and cognitive evaluation theories may influence future rangers. The potential impact of employment contracts (e.g. permanent vs temporary) on employee perceptions also warrants further consideration, specifically how such contracts affect perceptions of personal job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job insecurity (De Witte & Näswall, Reference De Witte and Näswall2003; De Cuyper et al., Reference De Cuyper, De Jong, De Witte, Isaksson, Rigotti and Schalk2007), as well as how these attitudes influence whether rangers actively socialize their children to pursue a career in conservation.

Discussion and debate on how best to manage conservation areas are likely to continue. Questions related to best practices, capacity building, and ways to engage local communities better will be the focus for many governments, policymakers, and conservation organizations. Such focus is undeniably important; however, more attention must be paid to the experiences, perceptions, motivations, and needs of those working at the front line of conservation, as these agents of formal social control are inherently representatives of conservation policy. Discussion on the increased militarization of conservation (e.g. Duffy, Reference Duffy2014; Lunstrum, Reference Lunstrum2014; but see also Shaw & Rademeyer, Reference Shaw and Rademeyer2016) has tended to neglect the experiences, viewpoints, and needs of front-line staff, and this is a notable omission as simply viewing rangers as efficient enforcers of the law or as military personnel rather than as people skews the reality experienced by these individuals (cf. McGregor, Reference McGregor1960; Dupré & Day, Reference Dupré and Day2007).

Better understanding of the experiences and perceptions of front-line staff will provide a more nuanced appreciation for the occupation, and insight into ground-level conservation initiatives, from a perspective that has been largely ignored. Only by incorporating such perspectives will researchers, practitioners, and policymakers be able to fully understand the human dimensions of conservation science and therefore be capable of developing the most motivated and effective ranger force.

Author contributions

WDM and JMG were responsible for conceptual development, analysis and writing. EAP was responsible for conceptual development and writing. RS, MB and BL were responsible for development of the survey instrument, data collection, and writing.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those involved in facilitating access to each of the study sites, as well as those responsible for data collection and collation. We are grateful to the governments of all participating countries for permission to conduct the study. We express our gratitude to all our study participants for their involvement. We thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions.

Biographical sketches

William Moreto is a criminal justice scholar and crime scientist, and his research interests include wildlife crime, wildlife law enforcement, and environmental criminology and crime prevention. Jacinta Gau is a criminal justice scholar and is interested in police−community relations, racial issues, and procedural justice and police legitimacy. Eugene Paoline is a criminal justice scholar and is interested in the study of police culture, police use of force, and occupational attitudes of criminal justice practitioners. Rohit Singh is an enforcement and capacity building specialist and is interested in ranger capacity building and ranger occupational perceptions. Michael Belecky is a policy manager and is interested in ranger capacity building and ranger occupational perceptions. Barney Long is Director of Species Conservation for Global Wildlife Conservation and is interested in protected area management effectiveness and ranger professionalization.