Introduction

The arrival of Ukrainian refugees to European countries after the Russian invasion of Ukraine brought many challenges to public policies, including the extent of temporary protection that was applied in different countries. This article takes the example of Poland and the Czech Republic to analyze the caveats of temporary protection in a yet unexplored setting. In doing so, it uses a multiscalar approach to analyze the evolution of the international temporary protection regime in a two-country case study. However, we also look at the EU level and the implementation of the temporary protection directive in the two respective countries. Lavenex and Piper (Reference Lavenex and Piper2022) describe regional approaches in the wider complex of global migration governance. They point to that we can distinguish the processes “from above” run through intergovernmental dynamics and “from below” run by transnational forces. They also show the variation and fragmentation of regional approaches, which generally fall into two groups: more legal- and political-science-oriented approaches that look at formalized institutional dynamics and more sociologically driven approaches that focus on the role of nonstate actors and civil society. Although the role of the latter was irreplaceable, our article falls in the former category. In the EU, there have been attempts at harmonization of immigration policies. Yet, it lagged in other policy areas (Givens and Luedtke Reference Givens and Luedtke2004).

Apart from the EU legislation, there is a global tool that addresses all kinds of migration-related situations. Along with the Global Compact on Refugees, the United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular MigrationFootnote 1 stresses the importance of national and regional practices in situations of humanitarian emergencies. It strives to

develop or build on existing national and regional practices for admission and stay of appropriate duration based on compassionate, humanitarian or other considerations for migrants compelled to leave their countries of origin owing to (…) other precarious situations, such as by providing humanitarian visas, private sponsorships, access to education for children, and temporary work permits, while adaptation in or return to their country of origin is not possible. (21e)

The situation of Ukrainian refugees’ arrival to Poland and the Czech Republic represents the case of a sudden influx of persons, which falls under the framework of the Global Compact. Interestingly, Poland and the Czech Republic were among the five countries that voted against the Global Compact in 2018 (along with the United States, Hungary, and Israel). This was in the light of both governments’ opposition to the “European refugee crisis” of 2015/2016 that was well above its peak once the compact was ratified by the majority of the states. Despite the Poland’s and Czech Republic’s disregard for the Global Compact for a global tool to manage migration, both countries acted rapidly on the Ukrainian refugee situation and offered refuge to hundreds of thousand people fleeing the war in Ukraine.

This article will focus on similarities and differences in the two national approaches. To do that, we will compare the steps taken by Poland and the Czech Republic, the former hosting the largest total number of refugees in absolute numbers and the latter in relation to the host country population. According to UNHCR (2024), there were 956,635 Ukrainian refugees registered in Poland in December 2023 and 381,400 in the Czech Republic in January 2024. The numbers show uniquely registered refugees for temporary protection and not border crossings from Ukraine (which would give even higher numbers). We would also like to point out the differences between the countries, which had a similar approach toward migration, and that both voted against the Global Compact. Although the situations of granting temporary protection have differed throughout history, we offer a glimpse into the current situation on the backdrop of the EU temporary protection directive, which represents a unique EU-wide legal tool. Nonetheless, the situation might differ in different countries based on their national, subnational, or municipal initiatives and the EU’s Council Directive 2001/55/EC offers only the minimum standards of temporary protection.Footnote 2 We ask the following research questions:

-

• What is the scope of temporary protection for Ukrainian refugees in the Czech Republic and Poland?

-

• What similarities and differences can be found in the basic legislation related to the temporary protection of Ukrainian refugees in the Czech Republic and Poland?

-

• What explains government response to the influx of Ukrainian refugees?

The presented analysis includes the period corresponding to the adoption of the basic legal framework for the protection of refugees from Ukraine, which in the case of the Czech Republic includes the period between February 24, 2022, and March 11, 2022, when the so-called Lex Ukraine was passed in the parliament. In the case of Poland, it focuses mainly on the period between February 24, 2022, and March 12, 2022, when the Polish “Special Law” was adopted. The article is divided into four parts. The first part explores the institute of temporary protection and provides a theoretical background to the research and understanding of temporary protection. Moreover, it discusses “deservingness” as a concept for explaining public policies toward their target groups. The second and the third part deal with the emergence and adaptation of the institute to the new reality caused by the influx of refugees from Ukraine. For the purposes of the article, we use the term “refugee” as a broad umbrella term for people who are fleeing from conflict situations and not within the meaning of Article 1A of the Geneva Convention. However, those who are provided with assistance might be more accurately described as “holders of temporary protection.” In these two parts, a general national framework is introduced with the intention of revealing national specifics in temporary protection institutes as formulated after February 24, 2022. Finally, the fourth chapter is dedicated to the discussion based on the main findings of the article and its implications for practical implementation.

The main method used in this article is a comparative analysis, which examines two similar cases in a very specific period. The two countries, whose institutes of temporary protection share many similar characteristics, created conditions in which the temporary protection law was approved. First, both countries were among those that were most affected by the migration influx from Ukraine. Second, both countries share geographical proximity and have similar the experience of being a postcommunist country, which is reflected in the legal and political culture. Finally, both countries are active members of the EU and implement its law, laying down minimum standards of asylum and migration policies with respect to democratic values and human rights. Yet, they are among the fiercest opponents of refugee relocation across EU countries, and they did not vote for the Global Compact, which shows a selectivity in the way in which they treat different groups of refugees. The authors believe that due to a relatively recent event and a very specific subject of analysis, the article will provide a complex and unique assessment of temporary protection mechanisms that have been designed in the region of Central and Eastern Europe and will place it within the context of existing literature. As a result, it might be an inspiration to other countries in the cases of unexpected migration situations, which will probably come more frequently in the future because of global challenges.

Temporary Protection and Deservingness

The temporary dimension in migration is a concept that is gaining salience because migrations are often fragmented and nonlinear (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou2022). The complexity of migrant pathways is especially significant in forced migration flows. The mass influx of refugees has taken place many times throughout history, and states across the world have responded to it by setting up different temporary protection schemes. Temporary protection (or temporary refuge) is a part of customary international law. It expects the states to grant refuge to those in a situation who are risking their lives due to armed conflicts or generalized violence (Lambert Reference Lambert2017). The temporary refuge is a “diverse and multifaceted” phenomenon, with “no single manifestation, purpose or character” (Gibney Reference Gibney1999, 690). However, temporary protection offers only short-term solutions. Therefore, it might be less suitable to be used in long-term, protracted conflict situations. Some scholars argue that there is a need for harmonizing minimum standards of protection among the states and greater responsibility sharing in those situations (Bastaki Reference Bastaki2018). This is due to the necessity of securing safe havens for those fleeing high-risk areas with the hope that sustainable return can be secured later. Some scholars also argue that temporary protection might be a solution to the international refugee protection crisis (Hathaway Reference Hathaway, Handmaker, de la Hunt and Klaaren2001).

Temporary protection offers fewer rights to refugees than the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Edwards Reference Edwards2012), which emerged after the Second World War. The 1951 Refugee Convention was temporarily and geographically bound at the time yet offered an individualized approach in opposition to the previous group (prima facie recognition) approach. One had to show that the refugees were targeted for persecution and not fleeing from generalized oppression and war (Bastaki Reference Bastaki2018). However, there was a need for continuation of the “group” approach, even after the adoption of 1951 Refugee Convention. Some international legal scholars such as Fitzpatrick (Reference Fitzpatrick1994, 410) have argued that international refugee law has become “increasingly irrelevant as a solution, especially in situations of mass influx.”

Durieux (Reference Durieux2014) characterizes temporary protection as concept, practice and principle. As a policy, temporary protection can be more difficult to define but can involve legal and administrative changes in countries that have adopted such measures (Koser and Black Reference Koser and Black1999). In practice, although not explicitly stated, refugee status equals permanent residence in many domestic policies, whereas temporary protection is offered for a limited amount of time. States that are not party to the 1951 Refugee Convention might offer temporary protection as a lesser form of international protection. However, due to other factors, this temporary protection might also extend to an indeterminate amount of time, and in that case, if the sustainable return is impossible, the practice of resettlement to third countries or material assistance is often expected for the most affected states (Lambert Reference Lambert2017).

All EU Member States are parties to the 1951 Refugee Convention and Protocol. EU law also distinguishes subsidiary protection and temporary protection. The subsidiary protection is granted to someone “who does not qualify as a refugee but in respect of whom substantial grounds have been shown for believing that …, if returned to his or her country of origin …, would face a real risk of suffering serious harm.” The serious harm is defined as “death penalty or execution” in Article 15(a) of the directive, as “torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” in Article 15(b), and as “a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in situations of international or internal armed conflict” in Article 15(c).Footnote 3

Temporary protection is defined in Article 2(a) of the Council Directive 2001/55/EC of July 20, 2001. This article further defines the minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and also measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences. Temporary protection is implemented in all Member States by a decision of the Council of the European Union confirming a mass influx of displaced people to the EU and stating the groups of people who need protection. The duration of the protection was initially one year and might be prolonged up to two years. It can end on behalf of the decision of the council that will claim that the return to the home country of the people is safe.Footnote 4 Temporary protection means “a procedure of exceptional character to provide, in the event of a mass influx or imminent mass influx of displaced persons from third countries who are unable to return to their country of origin, immediate and temporary protection to such persons, in particular, if there is also a risk that the asylum system will be unable to process this influx without adverse effects for its efficient operation, in the interests of the persons concerned and other persons requesting protection.”Footnote 5 A residence permit that is valid for the full duration of the temporary protection must be given to people who have this status. Those people will also have the right to be employed or self-employed, and they will have access to education, training, and work experience; suitable accommodation; social welfare; financial support; and medical care.Footnote 6

Although the Temporary Protection Directive was drafted only after the wars in the 1990s, many European states had offered refuge to refugees from former Yugoslavia, still emphasizing the right to return (Sopf Reference Sopf2001). In the 1990s, EU states dropped temporary visa requirements for ex-Yugoslav nationals or provided a form of provisional admission (Barutciski Reference Barutciski1994). Gibney (Reference Gibney1999) argues that European states, when granting temporary protection, may have been motivated by two main objectives: the humanitarian and the control objectives. The Temporary Protection Directive drafted in 2001, in the aftermath of the 1990s, was only activated in 2022 after the Russian invasion in Ukraine. The calls to activate it during the 2015/2016 Syrian “refugee crisis” went unheard (Ineli-Ciger Reference Ineli-Ciger2016). Although Türkiye implemented a form of temporary protection for Syrian refugees (Karaçay Reference Karaçay2023), the EU member states decided not to activate it. Germany, while not offering temporary protection, proclaimed its welcome culture (Willkommenskultur) through chancellor Angela Merkel and “welcomed” refugees from Syria. Some authors claimed that the ageing German population and pragmatic reasons played a role in this stance (Hannafi and Marouani Reference Hannafi and Marouani2023); others also pointed to the role of language learning, formal education, and securing employment as proving their status as “good refugees” (Etzel Reference Etzel2023). However, the attitude in Europe during the Ukrainian refugee situation differed markedly. According to Welfens (Reference Welfens2023, 1104), “European heads of states, some of which were among the hardliners in 2015 when Syrian refugees sought protection in the EU, highlighted not only Ukrainians’ suffering and protection needs but also their high educational level, added value for the economy and presumed like-mindedness to European societies due to shared ethnic and religious roots.” Through this we may see the connection to the concept of deservingness explaining the public policies toward some target groups.

Deservingness can entail the following dimensions—control, attitude, reciprocity, identity, and need, which have been listed under the acronym CARIN (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2000, Reference Van Oorschot2006). On the other hand, those who are in need of social protection because of controllable events such as unemployment are seen as less deserving (Jensen and Petersen Reference Jensen and Petersen2017). In other words, the public is open to sharing its resources through public policies directed toward the target groups that meet certain criteria: those who lack control over their challenging circumstances, exhibit the “right” attitude (such as demonstrating gratitude or compliance), potentially offer a return of support to the public in some manner (or have already earned it), with whom the public may identify for their proximity, and who are in a state of significant need (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2000; van Oorschot et al. Reference Van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Deservingness has also been discussed in relation to irregular migration and temporary labor migration programs, which have resurged (Castles Reference Castles2006; Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Reference Chauvin and Garcés‐Mascareñas2014). There is a tension between migrant deservingness and employment that has been summarized as follows by Chauvin, Mascareñas, and Kraler (Reference Chauvin, Garcés‐Mascareñas and Kraler2013, 82): “When employment becomes a source of rights and legality, policy makers may emphasise work as key to the definition of migrant deservingness, while simultaneously striving to limit migrants’ employment opportunities as a way to circumscribe their fuller access to civil rights.”

The term “promising victimhood” was coined by Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas (Reference Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas2018) to reflect on the ways in which refugees can be perceived based not only on their need for protection but also their supposed “integration potential.” Welfens (Reference Welfens2023) shows how “promising victimhood” is characterized by tensions between refugees’ vulnerability but also their willingness to overcome these constraints. She further highlights that social markers shape the assessment of both vulnerability and assimilability and adds how gender, race, and age play a role in understanding deservingness. She points to three dimensions of assimilability: (1) security, (2) economic performance, and (3) cultural “fit.” Although the former dimension is not listed in the CARIN dimensions, the latter two are connected with reciprocity and identity. The issue of “integration potential” is something that is mentioned more or less explicitly in many countries’ migration policies. At the same time, it has been discussed in relation to refugee resettlement. Integration aspects, such as the willingness of the refugee in question to be resettled to the Czech Republic and the willingness to integrate into Czech society, are also taken into consideration in the resettlement programs (Mourad and Norman Reference Mourad and Norman2020). Mourad and Norman (Reference Mourad and Norman2020) argue that this “picking and choosing” erodes the distinctiveness of the refugee category as a unique form of migration that is related to the need of protection, thereby redeploying the refugee regime for the purpose of obtaining highly skilled, “culturally similar” migrants.

Next, we will discuss how the Czech Republic and Poland reacted to the Ukrainian refugee situation of 2022. Both countries present a slightly different approach, as they were among the first countries who reacted and accepted high numbers of Ukrainian refugees. At the same time, although being geographically close and hosting significant Ukrainian minorities even before the outbreak of the war, they have different political or economic starting points.

The Case of the Czech Republic

On February 24, 2022, when Russia started its invasion of Ukraine, the Czech coalition government composed of five parties organized an extraordinary meeting in the Chamber of Deputies. In total, 165 (out of 200) present deputies approved an unanimous declaration condemning war against Ukraine: “[The Chamber of Deputies] categorically denounces the barbarian, inexcusable and unprovoked aggression by Russia against Ukraine, which breaches the basic norms of international law as well as principles of mutual relations between civilised nations and which threatens not only the lives of innocent people but the foundations of the European security architecture themselves.”Footnote 7 In the same document, the Chamber of Deputies expressed unanimous support for Ukraine and called on the Russian Federation to stop military aggression and withdraw its units from the territory of Ukraine to internationally recognized borders.Footnote 8 The meeting was attended by the Ambassador of Ukraine in the Czech Republic Yevhen Perebyjnis, and the PM Petr Fiala expressed guarantees to the citizens of Ukraine that they were safe in the Czech Republic and should not worry about prolongation of their visa (Seznam zprávy 2022). The unanimous support was partially surprising due to the presence of the hardline populists from the SPD party (Party of Freedom and Direct Democracy), which often promotes interests in line with the goals of Russian foreign policy and supports a friendly attitude toward Russia. The position of the SPD was later put on the “proper track” when, for example, not applauding the speech of the Ukrainian ambassador in the Chamber of Deputies or spreading pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives about the war.

Another meeting of the Chamber of Deputies took place on March 10, and the state budget was a dominant item on the agenda. Help to Ukraine was a topic of the next session scheduled for March 11, when the so-called Lex Ukraine was unanimously approved by 130 present deputies. Lex Ukraine invoked the EU temporary protection directive (Council Directive 2001/55/EC) and modified Czech Act no. 221/2003 Coll. (On the Temporary Protection of Aliens and other laws) to enable a flexible response.Footnote 9 In fact, Lex Ukraine is composed of three acts that are dedicated to individual issues of temporary protection: (1) The Act on some measures in connection to armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine caused by the invasion of the troops of the Russian Federation, (2) The Act on measures in the field of employment and social security in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine caused by the invasion of the troops of the Russian Federation, and (3) The Act on measures in the field of education in connection with the armed conflict on the territory of Ukraine caused by the invasion of the Russian Federation troops. The three acts will be summarized below to compare them with the Polish case.

The first act deals with the area of temporary protection and health insurance. According to the law, temporary protection shall be granted (for one year, but the law is in force only until March 31, 2023) to Ukrainian nationals residing in Ukraine before February 24, 2022, and their family members and applies also to the stateless persons and nationals of third countries other than Ukraine who were granted international protection or equivalent national protection in Ukraine before February 24, 2022, including their family members. Another group of people subject to the protection are those who proved that they were holders of a valid permanent residence permit in the territory of Ukraine as of February 24, 2022, and their departure to the state of which they are citizens, or part of its territory, or in the case of a stateless person, for whom return to the state or part of its territory of their last permanent residence before entering Ukraine is not possible due to the threat of real danger (§3).

Also, health insurance has extensive coverage because refugees from Ukraine who are subject to temporary protection are already insured by public health insurance from the date of entry to the territory of the Czech Republic. The public health insurance also covered children of parents from Ukraine who were born in the Czech Republic after February 24, and the law retroactively covered cases in which people received health services before the adoption of the Act.

The second legal instrument enabled free access to the labor market because refugees from Ukraine were considered permanent residents. Persons from Ukraine who were subject to temporary protection were allowed to participate in retraining courses or allowed to participate in self-employment. Moreover, temporary protection holders were entitled to benefits from the social system in the case of unemployment. The second issue covered was the humanitarian allowance of 5,000 CZK (approximately 200 Euro), which was provided on a nondiscriminatory basis to all incoming people from Ukraine after February 24. It is important to mention that people who are subject to temporary protection with insufficient income or in poor material conditions might have been granted repeated monthly allowance for a maximum of five months. It is necessary to mention that social services were provided free of charge and that there was a special program of solidarity allowance for hosts. Czech persons providing accommodation to the people subject to temporary protection free of charge received an allowance compensating the costs based on per capita basis/per household. Later, it was set to 3,000 CZK (approx. 120 Euro) per accommodated person, with a maximum of 12,000 CZK (per household and month, approx. 480 Euro). The new law also covered childcare in children’s groups. At the same time, the new law enabled qualifications approval for the people who worked in the provision of social service or in playgroups.

The area of education was covered by the third act, which enabled a special enrolment period for the children of Ukrainian refugees who wanted to place their children into kindergartens and primary schools. The law enabled the provision of intensive Czech language courses and assistance in integration, including psychosocial support. The law enabled directors of secondary schools, conservatories, and higher vocational schools to enrol foreigners in the first year (already ongoing). Similarly, in social services and playgroups, the law allowed staff from Ukraine to teach a group of students consisting of refugees from Ukraine without the need to know the Czech language. For universities, the rules to admit refugees were simplified.

To summarize, the initial response of the Czech government was relatively complex, enabling fast integration into the Czech socioeconomic environment. The explanatory report accompanying the above-mentioned legal acts is silent about the reasons for the relatively open and generous attitude of the government to extending health insurance, providing humanitarian allowance, or, in many respects, going beyond the minimum requirement set by the EU directive. However, from the context it is evident that the response of the government was pragmatic and systematic, reacting to the urgent need to legalize the stay of thousands of migrants with the potential to paralyze institutions or lead to economic and security damages: “Leaving this group of people in a legal vacuum might have resulted in a negative impact on the stability in the whole society. Similarly, it is important to mention potential economic damages which might be caused by the unmanaged migration flow” (Explanatory Report 2022). The later unpublished proposals for the explanatory report mention that due to capacity reasons opening a national social security system to refugees might have a disruptive effect on timely help and may also disrupt transfers for Czech citizens or that relatively higher support in the first six months of temporary protection shall help in the integration process and that after this period a “review” of the status will be made. From these intentions, it might be deduced that from early drafts the system was designed to help those who will integrate and later cut the support to the existential minimum to those who will not (except groups of vulnerable persons) to increase their motivation to participate in the labor market. As a result, it seems that the system was designed to create a “window of opportunity” for refugees on one hand and on the other buy the necessary time for the government to manage the flow and normalize the situation without exposing existing institutions and systems to a shock.

Retrospectively, a critical remark might be made. Despite the relatively generous scope of assistance, six months of humanitarian allowance reflecting a living minimum is a very short window of opportunity for comfortable integration of refugees, who had to leave a country within hours or days without previous preparation. Moreover, the system is ill-reflecting the structure of refugee flows. Technically, as mentioned in the explanatory report, the provisions have no grounds for discrimination or violation of gender equality. However, the migrants are composed mainly of women and children, which leaves fewer opportunities for women to find a job in a saturated market. As a result, assistance from NGOs and active citizens in helping people from Ukraine was essential from early on. Although a small part of the society was influenced by the pro-Kremlin narratives that were spread by the disinformation websites, most of the society still supported Ukrainian refugees. Yet, most of the Czech population was unwilling to host Ukrainian refugees (Dražanová and Geddes Reference Dražanová and Geddes2022), and that is why it was not recommended to rely on private citizen initiatives for a long time.

Due to the unsustainability of the measures, a revision of law soon entered into force, known as the Lex Ukraine II. It is not the intention of the article to cover all changes of the act, which entered into force on June 28, 2022.Footnote 10 However, most changes reacted to the practical implementation and measures taken. For example, as a result the period of maximal health insurance was set to 150 days; providers of free accommodation had a responsibility to report interruptions of migrants longer than 15 days (and losing allowances afterwards), and humanitarian allowance was bound to stricter rules (those who had free accommodation, full board, and all basic hygienic needs were not eligible). As a result, migration and integration incentives were gradually weakened. Since the original laws were declared on March 21, 2022, the Lex Ukraine was amended four times as laws 175/2022 coll.,Footnote 11 198/2022 coll., 20/2023 coll., and 75/2023 coll., with a fifth amendment in the legislative process (laws 175/2022 coll.). In comparing individual amendments, we might observe several trends.

First, under the Lex Ukraine V, the humanitarian allowance was cut from the original 5,000 CZK (200 EUR) to 4,860 CZK (194 EUR) and from the sixth month to 3,130 CZK (approximately 125 Euro) for adults and 3,490 for children (140 EUR). The exceptions are “vulnerable persons”—defined as children up to 18 years of age, persons taking care of children up to 6 years of age, students aged 19–26, pregnant women, persons older than 65 years of age, disabled persons, or persons taking care of disabled persons—are eligible for the multiplier from 1.2 to 1.5 of the sum (MoLSA 2023). Also, subsidies to cover living costs got severed, setting maximum values for registered apartments and nonregistered forms of accommodation, where assistance was much lower. It is important to note that subsidies match the life minimum set by the Czech law, which is 4,860 CZK (194 EUR) for adults and from 2,480 to 3,490 CZK (99 EUR to 140 EUR), depending on the age of the child (MoLSA 2023). The rationale behind cutting the allowances is necessary savings and the urgent need to consolidate public finances, together with increasing criticism of the government in providing help to Ukrainian refugees voiced by the populist opposition.

Lex Ukraine VI is accompanied by a special program assisting people who wish to return, as there are (relatively) safe places in Ukraine, which are not directly threatened by fighting. However, temporary visits to Ukraine are possible without losing the temporary protected status. As a result, there is an observable shift from Lex Ukraine I, providing relatively generous humanitarian assistance, to Lex Ukraine II, cutting main benefits, to the more formal Lex Ukraine III and IV, mainly extending the period for temporary protection, the relatively sustainable Lex Ukraine V, going closer to an existential minimum, to Lex Ukraine VI, starting to focus on returns. The ongoing trends reflect a pragmatic attitude of the Czech government in creating systemic incentives for Ukrainians for economic integration. Although there is an ongoing debate concerning whether the Czech social security system shall be opened to Ukrainians, Lex Ukraine is often criticized for deliberately pushing Ukrainians to poverty instead of motivating them to become fully independent, economically active persons (Consortium 2023).

The Case of Poland

Poland faced the biggest influx of refugees from Ukraine since the very first days of the Russian invasion. The war started at 4 a.m. CET, and at 6 a.m., the voivodes (i.e., the representatives of the government in the regions, so-called voivodeships) received the first instructions from the Ministry of the Interior and Administration regarding assistance to refugees. At about 10 a.m., the first reception centers near the Polish-Ukrainian border started their work.Footnote 12. Regardless of this, it must be emphasized that the greatest, most essential, and spontaneous assistance in the first days came from nongovernmental organizations, local governments, and individual volunteers. The regulation of the legal status of Ukrainian arrivals, together with further measurements concerning the aid, came only on March 12 when the Law on Assistance to Citizens of Ukraine in Connection with the Armed Conflict on the Territory of That Country (also referred to as the “SpecLaw” or “Special Law”) was published.Footnote 13 The Special Law—of a temporary character—is intended to complement or exist in addition to other applicable acts regulating the area of migration and asylum, in particular, the 2003 Act on Aliens and the 2003 Law on granting protection to aliens within the territory of the Republic of Poland.Footnote 14 It is a broad act of 116 articles introducing amendments to 24 laws (in its original version). Its main purpose was to determine the principles of legalization of stay related to Ukrainian citizens and their spouses who entered Polish territory directly from the territory of Ukraine and the citizens of Ukraine holding Card of the Pole, who, together with their immediate family members, arrived on the territory of the Republic of Poland. It also automatically prolonged the legality of the stay of these Ukrainian citizens who, in the regular circumstances, were supposed to either leave Polish territory in the weeks after February 24, 2022, or apply for prolonged stay permits. Moreover, the law opened a broad range of possibilities for assistance to Ukrainian refugees by the state, regional, and local governments as well as other subjects and individuals—at the same time, Polish institutions and organizations were allowed to offer help to their counterparts who were staying in Ukraine.

The general rule determined that the stay of citizens of UkraineFootnote 15 and their spouses who legally entered Polish territory from February 24th on and declared the intention to stay in Poland is recognized as legal for the period of 18 months from the date February 24, 2022, onward. Leaving Poland for one month during this time would not result in losing the legality of their stay after their return. Consequently, the rule allowed people to go back to Ukraine to address some urgent matters or to bring necessary documents. Significantly, already in the first version of the Special Law, Polish policy makers manifested farsightedness and thinking beyond the short period of a few months. The act envisaged that after the period of 18 months (at the earliest after nine months of stay), the Ukrainians who came to Poland after February 24th would be able to apply (once) for the stay permit for the period of three years.

One of the most important types of assistance was opening access to free medical care, including health care (apart from health resort treatment and rehabilitation) and administration of medicinal products. Another critical issue was opening the Polish labor market to this category of Ukrainian citizens, which meant that the employer was obliged only to register the name of the new Ukrainian employee in the local labor office within 14 days through an electronic system. Moreover, these Ukrainian citizens could be registered as unemployed or a person searching for a job (i.e., to use employment services and training), and they became allowed to run businesses in Poland on the same rules as Poles.

The law provided that all arrivals would obtain a national identification number (so-called PESEL), expanded by the UKR abbreviation, to easily specify persons to whom the number has been assigned by a special procedure. Ukrainians are supposed to apply for the number in person at any executive body of a municipality no later than 60 days after entering Polish territory. The number enables them to apply for a wide range of benefits and services. To facilitate Ukrainians’ access to public services, the lawmakers made Ukrainian citizens entitled to receive a so-called Trusted Profile (Profil Zaufany) to use the mobile application mObywatel.

Individuals who gained protection under the rules of the Special Law have the right to social assistance benefits on the same terms as Polish citizens. The Polish government enabled Ukrainians to receive, for example, family benefits, child benefits, “Good Start” benefits, family care capital, and subsidies to reduce the parents’ fee for the stay of a child in a day nursery, children’s club, or day care. An important rule is that a family member who does not reside in the territory of Poland (e.g., a father staying in Ukraine) shall not be taken into account when earning the right to family benefits, depending on the income criterion. Furthermore, Ukrainian citizens were entitled to obtain cash and noncash benefits from social assistance (on the principles and in the mode defined by the 2004 Act on social assistance) as well as to single cash allowance of PLN 300 per person (i.e., about 63 EUR) intended for subsistence (e.g., food, clothing, footwear, personal hygiene products, and housing fees). Among other types of assistance, there is psychological aid, food aid, and support for people with disabilities.

Facing the huge number of Ukrainian children, the Special Law also settled the rules for temporary guardians and foster care enabling Ukrainians to become foster families or to run foster family homes for Ukrainian citizens. Another essential set of rules concerned education (that is free of charge in public schools in Poland), which became available for Ukrainian pupils. The Special Law opened several solutions and introduced liberalization of some rules regarding schools, upbringing and care of Ukrainian children, and access to higher education for those who had been studying in Ukraine before the war began. Finally, the law enabled access to certain regulated professions—medical doctors and nurses—to facilitate Ukrainian citizens’ engagement in assistance to their compatriots.

Moreover, the law specified that the voivodes may provide Ukrainian refugees with accommodation and full-day collective catering, free public transportation, free cleaning, and personal hygiene products. Then each subject, in particular individuals, who provide Ukrainian refugees with accommodation and food, may gain a benefit of 40 PLN (about 8.5 EUR) per day per accommodated person for a maximum 60 days based on the contract with the municipality. As one may see, the anticipated assistance was expansive. To finance the help to Ukrainian refugees and to the subjects providing them with aid, a special Assistance Fund within a Polish Development Bank (Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego) was established. In addition, a few other funds became available to finance or cofinance the help to Ukrainian refugees.

The Special Law regulates a much broader scope of issues than are mentioned here. The act entered into force on the date of promulgation, with effect from February 24, 2022. It should be emphasized that there are many categories of foreigners that the Special Law does not concern. Those who do not fall into the scope of the act but who are covered by Article 2(1) and (2) of Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/382 of March 4, 2022, establishing the existence of a mass influx of displaced persons from Ukraine within the meaning of Article 5 of Directive 2001/55/EC and having the effect of introducing temporary protection (Official Journal of the European Union L 71, of March 4, 2022, 1–6), might apply for temporary protection, according to the Act of June 13, 2003, on granting protection to foreigners within the territory of the Republic of Poland.Footnote 16 Among them were Ukrainian citizens who did not come to the territory of Poland directly from the territory of Ukraine and their family members (who are not Ukrainian citizens); stateless persons or nationals of third countries (other than Ukraine) who enjoyed international protection or equivalent national protection in Ukraine before February 24, 2022, and their family members; and stateless persons or nationals of third countries (other than Ukraine) who able to prove that they were legally present in Ukraine before February 24, 2022, based on of a valid permanent residence permit but who were unable to return to their country or region of origin in safe and sustainable conditions. The temporary protection is provided for one year and will be automatically extended for additional six months for a maximum of one year if their safe return is not possible. Also, these foreigners gained free access to the labor market and became entitled to unemployment benefits and other unemployment allowances as well as access to education and higher education in Poland. Nonetheless, their rights (e.g., concerning social assistance) were much more limited than the rights of Ukrainians falling into the scope of the Special Law.

Since March 12, 2022, the Special Law has been amended several times based on experience with its implementation. Two weeks after its announcement, it was modified, and the target group became broadened to also include people who did not enter Polish territory directly from Ukraine. Gradually some regulations became improved, specified in more detail, or adjusted to the prolonging situation—for example, rules regarding unaccompanied minors (Dz.U. 2022, poz. 683), providing Ukrainian refugees with PESEL (Dz.U. 2022, poz. 830), or extending the period for which the hosts providing Ukrainian refugees with accommodation and food may receive a solidarity allowance from 60 to 120 days (Dz. U. 2022, poz. 930).

When the stay of refugees from Ukraine was prolonged, policy makers began to consider making changes to the existing system of support for foreigners to increase their labor activity. In January 2023, the amendment to the Special Law introduced the participation of Ukrainian refugees in covering costs of accommodation and food if provided by public entities. From March 1, 2023, a Ukrainian refugee who used this kind of support for 120 days had to cover 50% of the cost of this assistance in advance, not exceeding 40 PLN per person per day. Starting from May 1, 2023, it became effective that after 180 days from the date of the first entry of a Ukrainian citizen, assistance may be provided if covered for 75% of its costs, not exceeding 60 PLN per person per day. The vulnerable groups were excluded from the rules. Moreover, Ukrainian citizens covered by the scope of the Special Law, could gradually change their residential status. Starting April 1, 2023, it became possible for them to apply for a temporary residence and work permit, temporary residence for the purpose of conducting business activities, and temporary residence for work in a profession requiring high qualifications (Dz. U. 2023 poz. 185). Since the spring 2023, it has become apparent that the war would not end quickly. Thus, the April amendment extended the legal residence for Ukrainian refugees until March 4, 2024 (and for students in Poland, their legal stay is recognized until August 31 or September 30, 2024, so that they can finish their education (Dz. U. 2023, poz. 1088).

Comparative Analysis of the Czech and Polish Cases

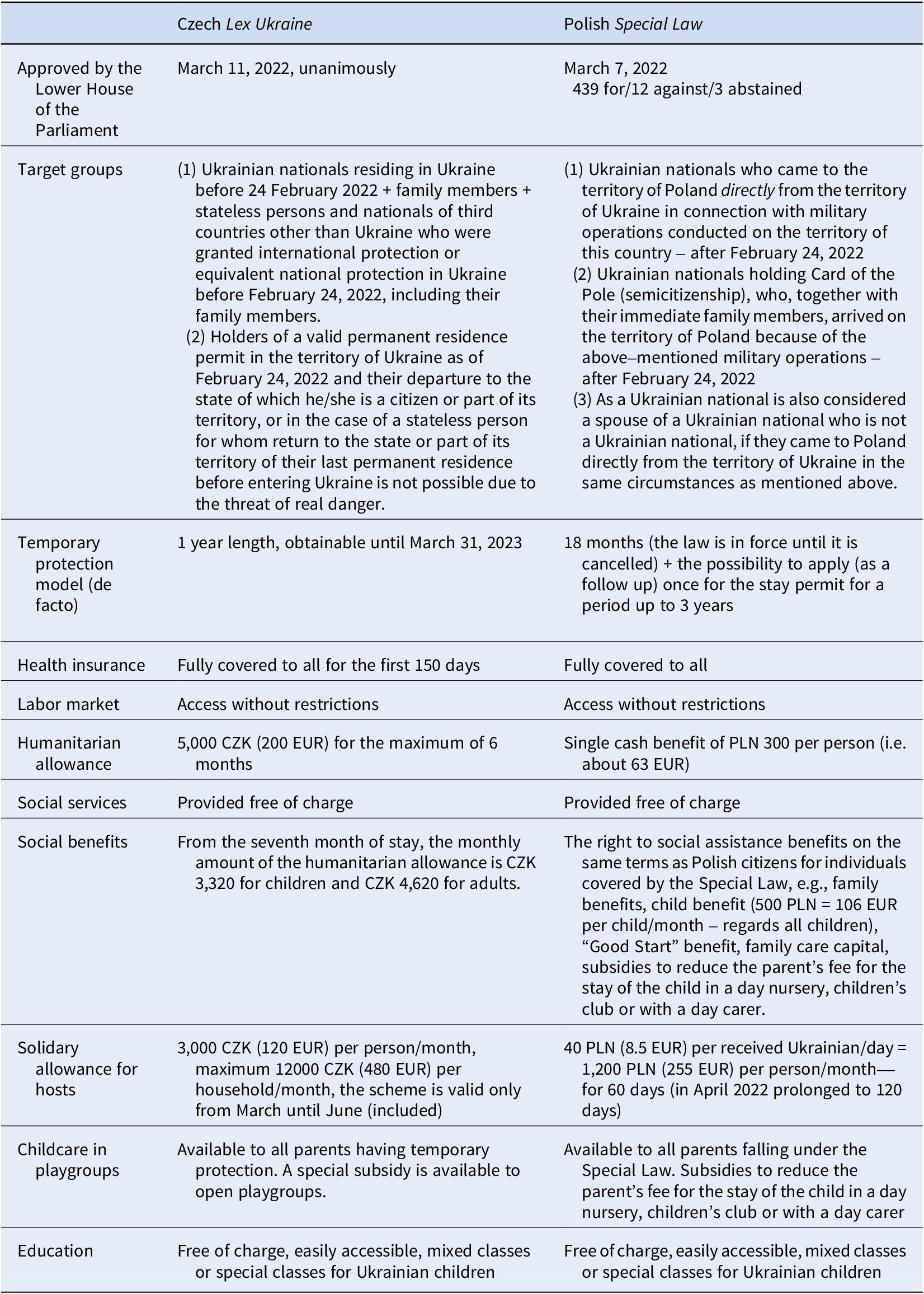

Table 1 compares the elementary features of the Czech and Polish models of temporary protection. In both cases, there is a complex set of norms that regulates not only territorial access but also access to other sectors of state, economy, and society. This is particularly important because the complexity associated with temporary protection is influencing the possibilities and motivation of refugees for integration and provides incentives for return or further migration.

Table 1. Selected Indicators of the Czech and Polish Temporary Protection Model According to the First Versions of the Relevant Legal Acts

Source: Authors.

In the Czech case, refugees from Ukraine have received special status within temporary protection with many advantages compared to those of holders of subsidiary protection. Even though the minimum standards of temporary protection are the same across EU countries, there are significant national differences. One example is the amount of humanitarian allowance, which was higher in the Czech Republic (about 200 EUR payment that can be repeated for up to five months) than in Poland (a one-time payment of 63 EUR). Whereas the Czech Republic offered an initial period of stay of only one year that might be extended (up to March 31, 2023) to up to three years, Poland offered an initial period of 18 months. Subsequently, Ukrainians who came to Poland after February 24 could apply (once and after initial nine months of stay) for the residence permit for three years. This wording is much more generous than the wording of the EU Temporary Protection Directive, which envisages a total period of protection of three years (with obligations to extend it periodically).

In both countries, access to education is granted free of charge at all levels. In the Czech Republic, enrollment of children from Ukraine in Czech schools was less than expected. According to recent figures, 67,000 children enrolled in Czech schools but, in reality, the attendance was lower—for example, due to return to Ukraine (MŠMT 2022). Although students could attend online schools in Ukraine in the first half of 2022, those residing in the Czech Republic were required to register to the Czech schools from September 2022. In Poland, students can only attend online in Ukrainian schools. Most children—an estimated 500,000—continue their education online in the Ukrainian system. The Polish minister of education and science informed that there were 185,000 Ukrainian children in Polish schools at the beginning of September 2022 (RMF24 2022).

In Poland, the Special Law allowed different forms of assistance and opened the possibility for additional forms of assistance (based on ministerial decisions or decisions of local government bodies). Also, it made proceeding with many administrative requirements and organizational solutions easier. An absolute example is that the executive authority of the municipality receiving applications for legalization of stay may confirm the applicant’s identity based on not only the passport but also the Card of the Pole or any other documents with a photograph that enables the identification of the person, including a document that has been cancelled. In case of a lack of documents, the identity could be confirmed based on the applicant’s statement.Footnote 17 The same was applied in the Czech Republic.

Discussion

There is a difference between the EU Temporary Protection Directive and the two national approaches. Although the EU Temporary Protection Directive (and the subsequent Act No. 221/2003 Coll. on the Temporary Protection of Aliens) offer the minimum standards, the adopted national legal framework taken after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is more generous. The directive targeted linking the measures across states for the reasons of “effectiveness, coherence and solidarity and in order, in particular, to avert the risk of secondary movements” (para. 9). Yet, this was not a major concern at the beginning of the situation despite the unprecedented refugee flows to both Poland and the Czech Republic. The directive first limited the duration of temporary protection to one year, which could be extended for a maximum of another year (the council could decide to extend the protection for another year, making a total of three years of temporary protection under the Council Directive). The total possible duration of stay (as of 2024) differs in the Czech Republic and Poland. Poland originally adopted a more generous approach, which allows for a better sense of security for the refugees.

The EU Temporary Protection Directive sets the minimum standards, and both Poland and the Czech Republic have been generous in their response to Ukrainian refugees. Despite minor differences, both countries have embraced helping Ukrainian refugees as a national task (Zogata-Kusz, Hobzová, and Cekiera Reference Zogata-Kusz, Hobzová and Cekiera2023). Our study discusses the legal framework that has been set up for this assistance. We will now discuss this assistance in the light of refugees’ “deservingness.” Deservingness refers to those who lack control over their challenging circumstances, exhibit the “right” attitude, such as demonstrating gratitude or compliance, and potentially offer a return of support to the public in some manner (or have already earned it)—reciprocity; those with whom the public may identify for their proximity; and, finally, those who are in a state of significant need (van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2000; van Oorschot et al., Reference Van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). So, why did Ukrainian refugees get such strong support from both states? The notions of refugees’ “deservingness” and “promising victimhood” might have played a role at the beginning in conceptualizing the laws regarding Ukrainian refugees.

The analysis of the context of the legal framework preparation in both countries enables us to explain why the assistance to Ukrainian refugees was so extraordinary and why Ukrainians were perceived as a target group deserving such assistance. First, in Poland, in the justification to the bill, and even more the debate in the Parliament, we may clearly see that the lack of control together with a great need, two elements of CARIN, are the most frequently repeated and the most explicit elements of Ukrainian refugees’ deservingness. The refugees are pictured as “the elderly, women, and children who enter Poland fleeing the horrors of war,”Footnote 18 “downtrodden women and children fleeing from hell.”Footnote 19 Similarly, in the Czech Republic, the minister of the Interior Vít Rakušan stated in the debate in the Senate that “we accept mothers with children, 80% of the total adult population are women, and of that total number of arrivals, almost 50% are children. If we then hear the populists say that there is a security risk, I am not afraid of the children.”Footnote 20

Importantly, shared identity with Ukrainian refugees was emphasized in the debates. The policy makers in Poland called Ukrainians not only our neighbors, Ukrainians, but also our brothers and sisters, friends, guests, which emphasizes identification with these people. Shared historical experience with Ukraine was highlighted in both Poland and the Czech Republic. The fact that Poles may identify with them is explicitly and implicitly visible in statements such as “what wars look like, I think everyone in Poland knows from either history or firsthand experience, as there are still many people who have lived through it. During those times and in those threats, we lived for many years.”Footnote 21 Similarly, in the Czech Republic, the minister of the Interior emphasized that as a “country that has such immediate historical experience, and after all, not so long ago, from 1968, when tanks invaded us and stayed here temporarily for more than twenty years, so we should be the first to offer help.”Footnote 22 Similarly, in the same debate, Šárka Jelínková mentioned that “citizens of the Czech Republic easily remember the summer of 1938, the year 1968. We Czechs understand Ukraine very well. We know it from history. We have it in our DNA.”Footnote 23

In the very first day of this stage of war, in the Polish President’s speech to the nation, Andrzej Duda talked about the war in the same spirit. Besides, he explicitly said that Ukrainians “defend not only their own freedom but the freedom of all of us—Europeans” (RP.pl 2022). Such a statement—made later by many other politiciansFootnote 24 includes a clear reference to the element of reciprocity from the CARIN concept: Ukrainians fighting for us earn our assistance. Similarly, the minister of education at the time mentioned that “Ukrainian children are already going to Czech schools, they are safe, their fathers can really defend their freedom and ours and feel good about the fact that their women and children are taken care of.”Footnote 25 Another speaker in the senate, Václav Láska, mentioned that except for “the expression of thanks and gratitude, it was also clearly expressed that we could do more, that we are not doing enough. And I think so too. It is not a criticism of the government or anyone else at all, it is more of a reflection on our European civilization. If we are really doing the most and the best we can, to protect both Ukrainians, but also to protect ourselves.”Footnote 26 This statement combines both elements of refugees’ attitudes and the reciprocity of the help. The only matter that has not been considerably visible in debates over the Special Law in Poland in the very first weeks is the question of refugees’ attitude. However, the policy makers emphasized the bottom-up enormous help that the ordinary people, local governments, and NGOs provided to newcomers opening their “hearts and wallets.”Footnote 27

The elements of CARIN encompass different dimensions. Although the concept and its application depend on the current socioeconomic climate in the host country, there is also the level of historical ties and shared values that can enhance this concept. Therefore, we could also add that the dimension of values, which is similar to “identity” but closer scrutiny, however, reveals that values are shaped by specific historical circumstances. Poland has a much closer relationship with Ukraine than the Czech Republic not only because of sharing a border but also due to historical closeness (Snyder Reference Snyder2002). At the same time, the historical experiences of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Ukraine have been shaped by historical grievances caused by the USSR, and the current situation can be described as a form of decolonization (cf. Budrytė Reference Budrytė2023). Therefore, the shared history of persecution can create a sense of closeness that supported countries’ engagement in helping refugees from Ukraine.

Another important marker of identity could be religious identity. Interestingly, countries with a higher percentage of religious population view refugees as more “deserving” due to moral reasoning, mobilized religious values, and resources (Galen and Miller Reference Galen and Miller2011; Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, McElroy, Aten, Davis, Van Tongeren, Hook and Davis2019). Therefore, Poland should have a greater tendency to accept Ukrainian refugees than the Czech Republic because a larger percentage of its population claims to be religious. However, religiosity did not show as important in our case studies because both countries, with different levels of religiosity, accepted refugees in a similar manner. At the same time, a different identity of “non-European” refugees played a role in the arguments of politicians who viewed Ukrainian refugees as being similar to the host country population and therefore, more deserving.

Although the dimension of security is not present in CARIN, it is a part of the term “promising victimhood” as conceptualized by Welfens (Reference Welfens2023). The Ukrainian refugee situation had been framed differently from the previous refugee situations in the region in terms of securitization, and Ukrainian refugees were perceived as a lesser security threat. Yet, their arrival brought many challenges to both countries. In the Czech Republic, the situation provided enough sources of criticism for the opposition, highlighting that the government of PM Petr Fiala is thinking more about refugees from Ukraine than about its own citizens. Critically, the opposition was labeling it as the “Ukrainian government of Petr Fiala,” which also resonated on many disinformation websites (see, for example, Česká věc 2022). With the changing atmosphere in society, existing measures were not sustainable and soon became the subject of the amendment (so-called Lex Ukraine II). It is paradoxical because measures were, from the early beginning, considered temporary, which had implications for effectiveness because public institutions (and refugees) had no certainty about the validity of rules after deadlines. It has been shown that although more than half of respondents from Germany think that their government treats Ukrainian refugees much or somewhat worse than themselves, more than half of Czechs think that their government treats Ukrainian refugees much or a little better than themselves (Dražanová and Geddes Reference Dražanová and Geddes2022).

In Poland, it is evident that the law was guided by the need to ensure widely understood security to the Polish state and its citizens as well as to Ukrainian newcomers. In the justification for the bill of the Special Law, the policy makers repeatedly emphasized the extraordinariness of the situation requiring immediate assistance to Ukrainian citizens, the need to be prepared for unpredictable development of the situation, including the unpredictable scale of migration, and the need for flexible and rapid response to the new circumstances. They called special attention to the needs of minors. An orientation toward coping with the situation rationalized resignation to various requirements in a range of issues and facilitation of access to some services. At the same time, the security rationale stayed behind the introduction of some measures (security of Ukrainian citizens, e.g., increasing punishment for human trafficking; security of the Polish state, e.g., provisions regarding technical infrastructure). An important justification for the whole bill was the temporary character of the act.Footnote 28

We shall emphasize that in the case of Poland, the Special Law virtually does not link to the EU Temporary Protection Directive. The act was not introduced in relation to the directive,and pertinent to it Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/382 of March 4, 2022, was mentioned neither in the justification to the bill nor during the parliamentary debate. Consequently, it seems that the Special Law would appear regardless of the EU legal solutions, even though we may envisage that it was influenced by them. The only link to the directive is pointing at the fact that the citizen of Ukraine whose stay is considered legal based on the Special Law is recognized as a person enjoying temporary protection within the meaning of article 106 (1) of the Act of June 13, 2003, on granting protection to foreigners within the territory of the Republic of Poland—that is, the act implementing the EU Temporary Protection Directive.

Conclusion

This article analyzed the immediate response of the Czech Republic and Poland after the outbreak of the Russian war against Ukraine on February 24, 2022, in the area of temporary protection mechanisms. These countries were the most affected by the influx of refugees from Ukraine (one per capita, second in absolute numbers), and both introduced temporary protection institutes with similar features to create a safe haven for new arrivals. The EU Temporary Protection Directive was drafted only in the aftermath of the war in Yugoslavia, and it was first activated in 2022. However, different states used different approaches to temporary protection based on various considerations (Edwards Reference Edwards2012). Temporary protection, as a general concept, offers fewer rights than a full refugee status does but has certain advantages, such as the speed of the process and access to the labor market for holders of temporary protection. At the same time, holders of temporary protection are also allowed to undergo a refugee-status determination procedure. The whole rationale for temporary protection rests on the assumption of return as a durable solution. However, it has been argued that temporary protection only works as an interim measure before the causes of escape can be solved or a burden-sharing mechanism is developed (Thorburn Reference Thorburn1995). Even today, return is seen as a preferred solution. Yet, so far, it is uncertain whether sustainable return will be possible after the maximum period allowed under temporary protection.

In both countries, the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine led to a societal and political consensus regarding helping refugees. This consensus was strengthened by the geographic and cultural proximity of refugees and the structure of the migration wave that consisted of many vulnerable groups, including women and children. In this respect, relatively generous help matched the public image of refugees deserving help. The design of the system of help was unsustainable from the very beginning, with a need to reconsider the scope of benefits for refugees and those providing them with accommodation. The response of the Czech government was pragmatic: creating a separate system for refugees, not threatening the existing institutional structure of social security, and buying time to manage the wave in the context of actual developments in Ukraine. Envisaged changes in the direction to cut the support later reflected weakening consensus in the society and an urgent need to consolidate public finances. The law targeting refugees from Ukraine in both selected countries was written in the spirit of reaching out to Ukrainian citizens and those willing to help them. The urgency of the situation requiring special solutions and compromises is evident. The trend over time is to incorporate Ukrainian refugees into various assistance systems that are already in place for the local residents. However, it is unclear what will happen after March 2025 when temporary protection for Ukrainians should end.

There are many similarities between the Czech Republic and Poland but also some differences. Although both countries are EU member states and have to follow minimum standards set by the Temporary Protection Directive, they adopted slightly different rules for Ukrainian refugees. There were some similarities in both countries such as refugees’ immediate access to the labor market and free education for children. However, there were also some differences. For example, the social assistance provided to Ukrainian refugees in Poland was provided on the same terms as the one for Polish citizens. This was not the case in the Czech Republic. The humanitarian allowance that was provided by the Czech Republic, which was higher than the one in Poland, targeted only Ukrainian refugees, but it was limited to the initial period. However, there was a trend of moving the refugees into the needs-based social assistance system targeting the Czech residents. Similarly, the Czech Republic introduced restrictions on health insurance after the initial period, which was in line with the rules for the local population. Poland did not have such restrictions.

The dimensions of CARIN were present in both case studies. On top of them, historical ties, which were present in our analysis, could present an additional dimension of this concept. Although historical ties are connected with identity, they nevertheless represent an additional lens through which deservingness can be understood. However, this dimension is not universal, as it only applies to countries with historical ties and will less likely be present in countries accepting refugees who do not share this level of closeness. Another dimension we encountered that is not included in CARIN is securitization. Welfens (Reference Welfens2023) shows that both vulnerability and assimilability are shaped by intersectional identity markers. The refugees from Ukraine were seen as a lesser security threat because they were categorized as “women and children” (Enloe Reference Enloe2014). The term “promising victimhood” lists security as one of its dimensions and, therefore, can be suitable for extension.

The liberalization of the rules during the Ukrainian refugee situation also concerned subjects and procedures that were directed at assistance to Ukrainians. It ranged from conditions for establishing clubs for children, using the school Internet connection in buildings of former schools currently providing accommodation for Ukrainians, through easing rules of hiring teachers’ assistants, to rules of public procurements. The urgency of the situation and the will to manage the unprecedented circumstances and protect people in need is almost tangible. Both countries witnessed an unprecedented surge in local governance initiatives. Among those was the introduction of free entrances to places of interest and free public transportation for Ukrainian citizens. It seems that many authorities have been inspired by each other, and the introduction of the schemes took place at a similar time in both selected countries. Nonetheless, further research is needed on specific areas (e.g., access to education, labor market, and health care) or individual features of temporary protection mechanisms. Concerning theoretical dimension, it would be possible to develop and define several models of temporary protection, which will help to systematize and clarify temporary protection mechanisms, providing a conceptual palette of instruments for policy makers and experts on migration. Temporary protection can mean different things in different regions; therefore, it is impossible to classify it in this article with a limited regional scope on the Czech Republic and Poland.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for their valuable comments and the special issue editors.

Financial support

This research was funded by IGA_CMTF 2023_010.

Disclosure

None.