Introduction

Achieving peace in post-conflict societies has proved to be an exceptionally elusive goal for the international community, including the European Union (EU). The EU, which is perceived as one of the most involved global actors in peacebuilding activities, relies on different mechanisms (e.g., EU-funded grassroots projects, civil and police missions, Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace [IcSP], Petersberg Tasks) in order to pave the way for the normalization of relations between hostile sides in post-conflict societies (Strömbom Reference Strömbom2019). However, when talking about the post-conflict societies in Europe, the EU relies on a different kind of mechanism, which allegedly has the greatest potential for genuine conflict transformation – the process of European integration. European integration, which according to Manners and Murray (Reference Manners and Murray2015, 190) sought to create a “common (European) space without antagonisms,” refers to the idea of peace and postwar reconstruction of Western Europe after the Second World War. Such an idea only functioned until the EU enlargement in the 1990s and 2000s, when the newly consolidated states of Central and Eastern EuropeFootnote 1 could not exclusively identify with it (Mälksoo Reference Mälksoo2009). Those states predominantly understood European integration through the idea of stability (meaning that integration in the EU would make countries more stable). This stability, along with historical memory and reconciliation, were becoming a part of a stable narrative that the EU and its European integration represents (re)solution for post-conflict issues due to the ability to provide (material) means and/or grounds for overcoming antagonisms through transformation of identities (Noutcheva Reference Noutcheva2009; Subotić Reference Subotić2011).

This context is particularly pertinent for the post-Yugoslav space, which from 1999 onwardFootnote 2 has been subjected to the process of European integration via the Stabilization and Association Process (SAP) – EU’s policy toward the post-Yugoslav space, established with the goal of securing eventual EU membership (Aybet and Bieber Reference Aybet and Bieber2011). This process constitutes the framework of relations between the EU and post-Yugoslav states, with the final aim of signing the Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA). The SAA, which marks an important step of potential candidate country toward full EU membership, appears – in a “doxic”Footnote 3 manner – as a sign of an overall sociopolitical “progression and development,” something that the potential candidate country could only “benefit from” (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2019; Zupančič, Kočan, and Ivaniš Reference Zupančič, Kočan, Ivaniš, Halas and Maslowski2021). But for Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), a country where the division along ethnic lines is not only obvious but de jure “set in stone”Footnote 4 via the Dayton Peace Agreement (DPA) – an agreement that ended the war and prescribed the post-conflict reality of BiH – both SAP and SAA are not straightforwardly translated into an overall “success” or “progression.” This is particularly clear in the case of Republika Srpska (RS),Footnote 5 one of the two subnational political entities in BiH (the other being the Federation of BiH [FBiH]), where predominantly Bosnian Serbs live, and where there is only 58.9% support for the integration of BiH in the EU (comparatively speaking, in FBiH, 86.5% of people support the integration of BiH in the EU) (European Integration Directorate 2019). As Turčilo (Reference Turčilo2013, 7–8) pointed out, there are at least three arguments for lower support for integration in RS: (1) the EU accession process is perceived as something that could jeopardize the existence of the RS, (2) the EU accession process is perceived as something that could guarantee the continuation of BiH as a state, and (3) the EU accession process is perceived as something that could offer an external solution to the internal division of BiH. RS is therefore an empirical focus of this article, whose insights contribute to the ongoing scholarly debates within Ontological Security Studies (OST), which show how European integration and the EU can also contribute to existential anxieties in post-conflict societies, primarily in cases such as Cyprus, (Northern) Ireland, and Serbia vis-à-vis Kosovo (Rumelili Reference Rumelili2015, Reference Rumelili2018; Manners Reference Manners2018; Kinnvall, Manners, and Mitzen Reference Kinnvall, Manners and Mitzen2018; Ejdus Reference Ejdus2020).

As Biermann (Reference Biermann2014, 500) clearly pointed out, the period from 2005 onward,Footnote 6 when BiH negotiated for the SAA, is understood as a period of regression. Numerous authors (e.g., Muehlmann Reference Muehlmann2008; Richter Reference Richter2008; Juncos Reference Juncos2013) have shown that this period, which coincided with the EU’s efforts toward a “more functional state,”Footnote 7 was inevitably linked with the idea of transfer of (political) competencies from two subnational political entities (RS and FBiH)Footnote 8 to the state level. By advocating for police reform (Juncos Reference Juncos2011; Reference Juncos2017), openly promoting a constitutional debate (Muehlmann Reference Muehlmann2008; Biermann Reference Biermann2014) during the SAP and even understanding police reform as a prerequisite for the signing of the SAA, the EU opened a “Pandora’s box of a power-sharing system that no one was fully satisfied with but prudent politicians had refrained from contesting” (Biermann Reference Biermann2014, 500). The discussion on a power-sharing system, which began during the SAP, has been haunting BiH’s sociopolitical landscape ever since – be it the Prud and Butmir processes in the period between 2008 and 2009,Footnote 9 the “referendum rhetoric” in the period between 2009 and 2013,Footnote 10 or the unconstitutional referendum on the Day of RS in 2016. Here, it has to be pointed out that the efforts to endorse the constitutional reforms ended by 2009 and were – after the failed police reform – less forceful (Bieber Reference Bieber2010). In all of those cases, the ethnopolitical elite from RS framed such events as a “threat” to the very existence of their political entity, its “territorial integrity” and/or autonomous political institutions, and they exploited the potential of using “extraordinary measures” – the unconstitutional referendum on RS’s independence. Furthermore, they have used the negotiating process for SAA as a means to further antagonize the relations with “official Sarajevo” and Bosniak political elite FBiH, while framing the EU and Office of the High Representative (OHR) as institutions that “coordinated the reform agenda with Bosniak political elites and impose it on the RS” (RTRS 2005a; 2006a; Glas Srpske 2006a; Nezavisne novine 2007a). Such (antagonistic) discourse, which was promoted during the SAA negotiations process (2005–2007), is to a large extent still present in RS’s sociopolitical landscape, along with the ruling political party that has successfully consolidatedFootnote 11 it throughout these years (Savez nezavisnih socijaldemokrata – SNSD) (Toal Reference Toal2013; Kartsonaki Reference Kartsonaki2017; Hulsey and Keil Reference Hulsey and Keil2020).

Focusing on the case of RS, the research question of the article is, therefore, “Why and how did the securitizing actors (political elite) from RS manage to successfully frame the alleged ‘overall progress, development, and success’ deriving from the SAA as a failure and as a mechanism for further division along ethnic lines instead of something that could potentially mitigate the antagonisms between ethnic groups?” In order to answer this, the article draws on securitization theory by identifying the grammar of security, the wider discursive context, and the position of power and authority that existed in RS during the period of negotiating the SAA. Methodologically, we combine content and discourse analysis, as proposed by Ejdus and Božović (Reference Ejdus and Božović2016). Whereas the content analysis offers quantitative insight into security speech acts present in the media coverage of the 2005–2007 SAA negotiation process, the discursive analysis enables qualitative reflection on the securitization dynamics during this period. Even though we acknowledge the epistemological tension between content and discourse analysis, Ejdus and Božović (Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 2) demonstrate with the proposed methodological framework the “analytical added value of such methodological triangulation.”

The article is divided into four sections. The first briefly introduces and discusses the theoretical framework of securitization that underpins this study. The second explains the methodology and the background of the content and discourse analysis. The third offers the results of the analysis and discussion. And the fourth – the conclusion – reveals the theoretical and empirical implications of our case study and proposes some avenues for future research.

Theoretical Framework of Securitization and its Operationalization

Securitization, in essence, reflects on a process where a particular (political or social) challenge is shaped by political elites as a security problem, which, by entering the public space, becomes perceived as an existential threat to a certain referent object (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998; Wæver Reference Wæver2004). This theoretical paradigm was developed by Ole Wæver (Copenhagen School), who rethought the notion of security as a “speech act.” This means that security is “an utterance in itself” and should be understood within the paradigm of “by saying something, you are already doing it (Wæver Reference Wæver1989, 5). A speech act is executed by a securitizing actor, who frames something or someone as an existential threat to a particular referent object and proposes/advocates for “extraordinary measures” (Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 3), which are understood as measures that could not be introduced under “normal conditions”Footnote 12 and without the support of an audience (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998). Here, we have to emphasize that the central premise of securitization theory is that it is not an objective or given condition, but rather a discursive act, given that only labeling something or someone as an existential threat becomes a security problem. Recognizing that a possible extension of the concept of security can lead to incoherence, and that it is necessary to limit ourselves conceptually to prevent the creation of the logic that “everything can be the subject of analysis,” the Copenhagen School emphasizes that security must be defined as more than just a problem or vulnerability (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998). When the Copenhagen School talks about security, it talks about “survival in the context of existential threats” and not about all the “bad that can potentially happen” (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998, 27). Framing something as an existential threat is therefore the focal point for the analysis of securitization, but this does not mean that every security threat that threatens the existence of a referent object is automatically subjected to successful securitization. By having been defined in a seminal book in 1998, securitization has moved away from being understood as merely a linguistic process and has gained a sociopolitical dimension (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998).

In the past 20 years or so, securitization theory has become an ever-evolving theoretical framework that is tackled from various standpoints and perspectives (McSweeney Reference McSweeney1998; Bigo Reference Bigo, Kelstrup and Williams2000, Reference Bigo2002; Williams Reference Williams2003; Theiler Reference Theiler2003; Balzacq Reference Balzacq2005, Reference Balzacq2010, Reference Balzacq, Cavelty and Balzacq2012; Booth Reference Booth2005; Huysmans Reference Huysmans2006; Stritzel Reference Stritzel2007; Doty Reference Doty2007; Roe Reference Roe2008; Salter Reference Salter2008; Vuori Reference Vuori2010; Hansen Reference Hansen2011; Adamides Reference Adamides2012; Croft Reference Croft2012; Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016). During this period, scholars have managed to position themselves within three overarching schools of thought – namely, (1) the Copenhagen School (e.g., Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998), (2) the Paris School (e.g., Bigo Reference Bigo2002; Balzacq Reference Balzacq, Cavelty and Balzacq2012), and (3) the Welsh SchoolFootnote 13 (e.g., Booth Reference Booth2005). Here, we have to highlight that the majority of academic debates are grounded within the Copenhagen and Paris Schools, both of which are important for the purposes of this article. If the Copenhagen School is understood as a philosophical approach due to its strong roots in speech-act theory, the Paris School is framed as a sociological approach due to the focus on practices, context, and power relations that underpin threat images (Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 3). We argue that broadening securitization theory by involvement of the Paris School is – for the purpose of this article – beneficial. This stems from the fact that the Paris School understands securitization as an argumentative process (rather than a speech act that serves more as a one-off mechanism), allowing the inclusion of various forms of political manifestations during the securitization process (Bigo Reference Bigo2002; Balzacq Reference Balzacq, Cavelty and Balzacq2012).

While acknowledging the rich opus of literature that tackles securitization theory from different angles, there is still an overarching question all scholars are touching upon – i.e., under which conditions a securitization act succeeds. The Copenhagen School – inspired by Austin’s and Worchel’s (Reference Austin and Worchel1979) conceptualization of felicity conditions – offers three conditions for successful securitization. First, the discursive act has to follow the grammar of security by setting a context where something or someone is perceived as an existential threat, framing it as “point of no return,” and offering a strategy of a “possible way out” (Buzan, Wæver, and De Wilde Reference Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde1998, 33). Second, the securitizing actor has to possess (or construct an illusion of possessing) both political power and authority. Finally, the securitizing actor has to facilitate the conditions in which certain aspects of the existential threat are historically related to it (Wæver Reference Wæver, Guzzini and Jung2003). The Paris School of securitization shares certain similarities with the conditions that were laid down by the Copenhagen School, but instead of framing the success of a securitizing act through “conditions,” the Paris School operates within the context of “layers” (Stritzel Reference Stritzel2007). In that regard, the biggest difference between the first condition (Copenhagen School) and first layer (Paris School) lies in the inclusion of symbolic language of visuals/images and sound (broadening the discursive act as a merely linguistic phenomenon) (Strizel Reference Stritzel2007, 370). Whereas the second layer focuses on the “embeddedness of the text in existing discourses,” the third builds on the “positional power of actors who influence the process by defining meaning” (Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 4).

In this regard, the Paris School builds its “distinctiveness” in relation to the Copenhagen School mainly vis-à-vis weak definition of the development of a discursive act, which is “too broad” in relation to other practices of power (Bigo Reference Bigo, Kelstrup and Williams2000, Reference Bigo2006). By doing this, the Paris School argues that security practices are subjected to a set of unique dispositions of a particular social context, which means that the identity, political views, and social norms of both the securitizing actor and the audience are decisive during the securitization process (Balzacq Reference Balzacq2005; Adamides Reference Adamides2012). The latter is therefore what Balzacq (Reference Balzacq2005, 172) understands as dispositive, or the psychocultural disposition of the audience. However, as Aradau (Reference Aradau2004, 392) lucidly states, such conceptualization does not differ radically from the Copenhagen School – it just gives greater emphasis on practices, audiences, and contexts, which enables the construction of a specific form of governance. Putting greater emphasis on the audience was particularly welcomed in the debates on securitization theory. This was done by Balzacq (Reference Balzacq2010), one of the core authors of the Paris School, who argued that the force of securitizing moves rests with the audience and further decoupled the concept by differentiating between the “moral” support by the audience and the “formal” support of the institutions when adopting extraordinary measures (Balzacq Reference Balzacq2005, 184). As Ejdus and Božović (Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 4) argue, “the more congruent they are, the more successful a securitizing move is.” Here, it has to be clarified that even though “success” and “failure” of a securitizing move as two categories coincide with Weber’s (Reference Weber1947) ideal types capturing the (most) essential components of social things, we rather follow Salter’s (Reference Salter2008) idea of “success” as some kind of continuum. Salter’s (Reference Salter2008) critiqueFootnote 14 therefore follows the argument that the success of a securitizing move is rather a question of degree (high, medium, low).

Before turning to the analysis of securitizing moves made during the 2005–2007 period, which is when the negotiations of the SAA unravelled, we have to offer operationalization of security practices based on the above-sketched trajectories, which we are going to use in the content and discourse analysis. Many authors have attempted to design appropriate operationalization in order to measure the (degree) to which the process of securitization is (un)successful, its wider discursive context, and the position of power that underpins such process. Consequently, the first element of operationalization is polarization – authors such as Ejdus and Božović (Reference Ejdus and Božović2016) and Fermon and Holland (Reference Fermor and Holland2019) show that there is a positive correlation between a high degree of polarization and the intensity and frequency of securitizing acts. The second element is treatment option, which analyzes the securitizing actor’s preference on finding a “solution” for the problem (Coskun Reference Coskun2011; Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016). The third element is emotions. This is because the theory assumes that the level of emotionality has a positive effect on the persuasiveness of the securitizing actor on the audience via media outlets (Van Rythoven Reference Van Rythoven2015; Hagström and Hanssen Reference Hagström and Hanssen2015; Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016). The fourth element is media bias, because the theory presupposes that the higher the bias, the bigger the polarization in the society (Vultee Reference Vultee2010, 91; Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016, 7). The fifth element is access to the media. This is important because equal access to media offers an understanding of the power of the securitizing actors and its credibility vis-à-vis both the referential object and opposing “camps” (Endres, Manderscheid, and Mincke Reference Endres, Manderscheid and Mincke2016; Ejdus and Božović Reference Ejdus and Božović2016; Hintjens Reference Hintjens2019). Finally, the sixth element is reference to the past, because both Paris and Copenhagen Schools argue that the securitizing actor has to facilitate the conditions under which either certain aspects of the existential threat are historically related to it (Wæver Reference Wæver, Guzzini and Jung2003) or the process of securitization in itself is determined within the actor’s own historical and memory limitations (Balzacq Reference Balzacq2005, 172).

Methodology: Designing the Experimental Codes for the Content and Discourse Analysis

As already stated in the introduction, the article follows the methodology and operationalization of the variables as proposed by Ejdus and Božović (Reference Ejdus and Božović2016). The main reason for this is that by combining qualitative (discourse analysis) and quantitative (content analysis) methods, we can offer a more complex and nuanced insight into securitization dynamics. Furthermore, Baele and Thomson (Reference Baele and Thomson2017, 646) have argued that by combining qualitative and quantitative analysis, one could “mitigate some of the program’s methodological weaknesses” and “help explain when securitizing moves are likely to succeed or fail.” Deriving from this, the systemic use of content and discourse analysisFootnote 15 of the 2005–2007 SAA negotiations in BiH helps us understand the presence of discursive acts, their resonance, and their level/degree of success. For the purposes of content and discourse analysis, we have used the archives of two print and two broadcast media outlets with online media articles: Radio Television of Republika Srpska (Radio Televizija Republike Srpske – RTRS) and Radio Television of Bijelina (Radio Televizija Bijelina – RTV BN), which are broadcast media outlets with online media reports; and Nezavisne novine and Glas Srpske, which are printed media outlets. The content and discourse analysis covered 1,769 unitsFootnote 16 published between January 2005 and December 2007, and the units of analysis were online articles and newspaper articles. The reason for scrutinizing the content of these four media outlets lies in their outreach in RS. The analysis by Petković, Bašić Hrvatin, and Hodžić (Reference Petković, Hrvatin and Hodžić2014); and Vukojević (Reference Vukojević2015) has shown that approximately 22.2% of the population in RS reads Glas Srpske, 18% Nezavisne novine, 17.5% RTRS, and 6.7% RTV BN.

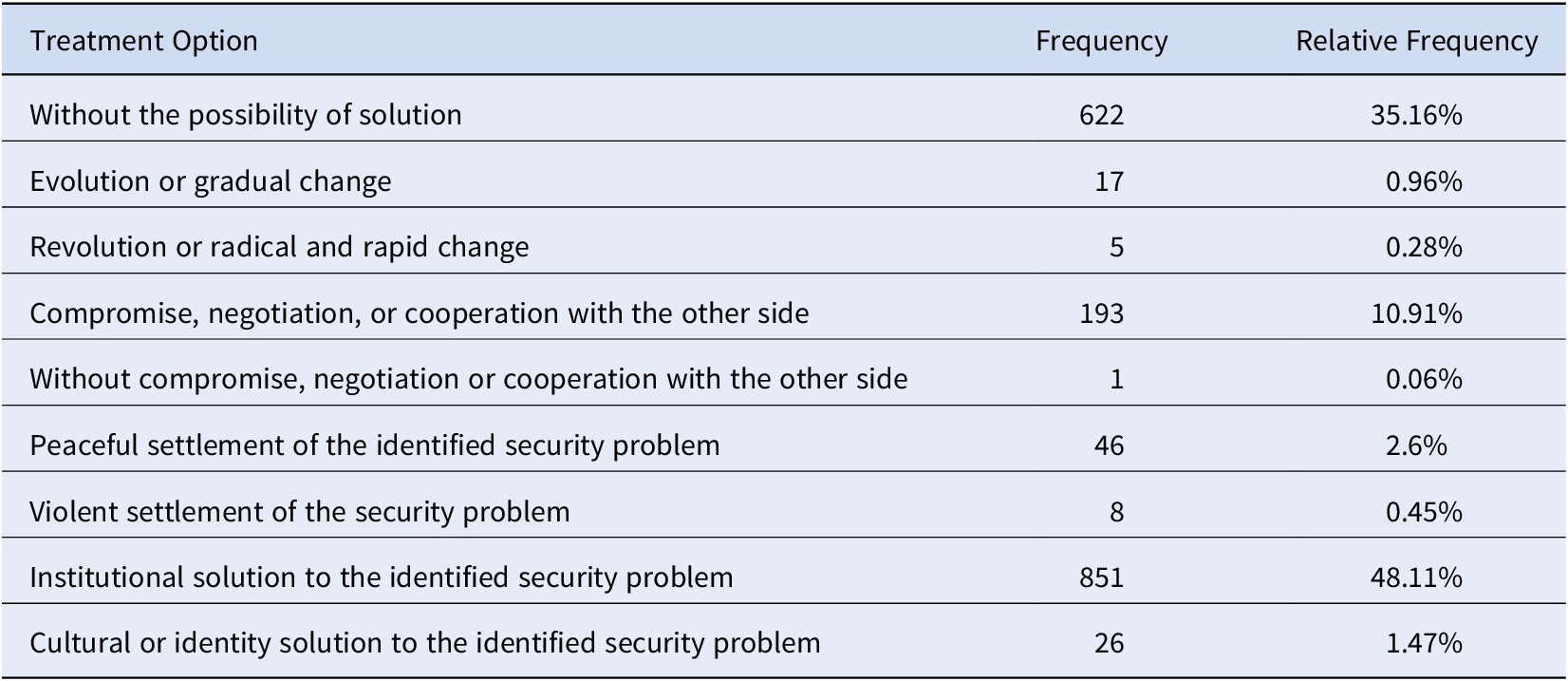

The first variable that we used in our analysis, polarization, was coded with four levels: 0 – no polarizing language; 1 – moderate speech (language based on facts); 2 – partially polarizing language (moderate criticism); 3 – strongly polarizing language (unbridgeable differences). The second variable, treatment option, defines preferences of tackling a challenge that is framed as a security problem. This variable was coded with five stages, in which all codes (except 0) had two diametrically opposite ends, denoted by (a) and (b): 0 – without the possibility of solution; 1a – evolution/gradual change; 1b – revolution/radical and rapid change; 2a – compromise/negotiation/cooperation with the other side; 2b – without compromise/negotiation/cooperation with the other side; 3a – peaceful settlement of the identified security problem; 3b – violent settlement of the security problem; 4a – institutional solution to the identified security problem; 4b – cultural/identity solution to the identified security problem. The third variable is emotions, which are coded with three levels: 0 – nonemotional; 1 – moderately emotional; 2 – extremely emotional. The fourth variable, media bias, is coded with five stages: 0 – neutral (does not contain biased message); 1 – balanced (contains biased message, but these are balanced on (both/all) sides); 2 – moderately biased; 3 – biased. The fifth variable, access to the media, is measured with the following codes: 0 – balanced representation; 1 – unbalanced representation. In addition, the aim of this code was to identify who is present as the securitizing actor and who possesses relative (structural) power, which led us to use the subvariables “voice 1,” “voice 2,” and “voice 3” in a coding book. Finally, the sixth variable is the reference to the past or its revival, which was encoded with respect to the “breakpoints” of BiH’s history: 0 – without reference to the past; 1 – Second World War; 2 – common life in former Yugoslavia; 3 – disintegration of Yugoslavia and referendum on the independence of BiH and RS; 4 – NATO intervention in BiH; 5 – Bosnian War (1992–1995); 6 – Kosovo question; 7 – other historical events.

The Analysis of the 2005–2007 SAA Negotiations in BiH: Results and Discussion

Content analysis of 1,769 media articles has showed that in 68% of the cases no negative language (polarization) was noticed. Moderate, fact-based speech was used by securitizing actors in 11.5% of the articles, and partially polarizing (16.2%) or strongly polarizing language (4.3%) was identified in 364 articles (20.5%). A relatively similar trend can be observed in the analysis of emotions. In 71.2% of cases, there was no negative language, 22.6% had moderately emotionally marked speech acts, and 6.2% were extremely emotional. Here, it should be emphasized that polarization (and the associated emotional undertone of the discursive acts) in the identified 20.5% of cases took place at three levels: (1) within the RS and primarily by the SNSD against the SDS; (2) outside the RS and primarily against the “Bosniak” ethnopolitical elite, both on the level of FBiH and BiH (“internal Other”); (3) outside RS and primarily against international actors (“external Other”).

The analysis has shown that polarization in RS (Table 1) was mainly carried out by the SNSD and its president Milorad Dodik, which was not directly related to the process of SAA negotiations. Instead, it was used in the negotiations as a context for projecting the image of the SDSFootnote 17 as the party that is supported by the international community within its reform efforts (Nezavisne novine 2007a, 2; Glas Srpske 2007a; RTV BN 2007a). For example, Milorad Dodik began to emphasize that he “has information that SDS is in talks with the international community about entering in the coalition,” with which “the party want to put its ‘pot’ to external influences with the aim of breaking the unity of the SNSD” (Nezavisne novine 2007a, 2). In terms of internal political polarization, we should note that even when SDS was in power, “the party’s council did not agree with the support of the three EU principles”Footnote 18 (Glas Srpske 2005a, 5). Here, we should also stress that there was polarization within the coalition as well, given that the leader of the Socialist Party of RS Petar Dokić emphasized in 2005 that “SDS policy lost because the leadership for years and years argued that it would not allow any changes and that it would protect RS from external influences at any costs” (RTV BN 2005a).

Table 1. Polarization in the Period between 2005 and 2007.

Source: Own analysis.

Unlike the polarization within the RS, which took place with the aim of maintaining internal political legitimacy or/and the ruling position, the polarization “outside” the RS (toward [F]BiH) and the securitization of the “internal Other” (especially the Bosniak political elite) was more intense. This started relatively early, in May 2005, when Petar Kunić, former member of the RS parliament and minister of public administration, emphasized in a column in Glas Srpske (2005b) that reform efforts aimed at signing the SAA are a “reform soup of the official Sarajevo’s political kitchen” and therefore they are “not acceptable to all sides in BiH.” A similar position was taken by Nikola Špirić (SNSD), who framed a member of the Bosniak political elite Adnan TerzićFootnote 19 as “replaceable” and someone who “does not have the support by the international community in reforms, but in humiliating others who ‘should’ but do not participate in such reform efforts” (Nezavisne novine 2005a, 6). About nine months later, Petar Kunić further instrumentalized this discourse in his second column in Glas Srpske (2006a, 52) by arguing that the “centralization of BiH – immediately after the break-up of the former Yugoslavia – is a Bosniak idea.” Furthermore, Kunić argued that “the Bosniak lobbyists have been exploiting European integration since the Bosnian War in order to centralize the country” (2006a, 52). In addition, Dragan Čavić – the president of RS – just before handing over power to the SNSD, stressed that “any deviation from the DPA would be a return to the previous status of the RS as a state, which would not satisfy anyone, not even Bosniaks, who fully identify with the state level” (Glas Srpske 2006b, 5).

Polarization began to intensify after the political change, which was ensured by Milorad Dodik’s (SNSD) speech acts. Already in August 2006, he began to ground his rhetoric on the alleged “unbridgeable” differences between RS and (F)BiH when, during the talk on joint solutions to challenges in BiH, he stressed that “BiH’s political parties can find a solution to every issue in BiH, but not with incompetent jugglers like Adnan Terzić” (Nezavisne novine 2006a; RTRS 2006a). Such an attitude toward the “internal Other” (the Bosniak political elite) continued in 2007, when Dodik said that “no one is crazy enough to believe that the reform proposals are not in line with Sulejman Tihić,”Footnote 20 and that “this situation was already seen 20 years ago when the majority (Bosniaks) did not want to listen to others” (RTV BN 2007b; Nezavisne novine 2007b). A similar argument was voiced by the President of the Democratic party of Srpska (Demokratska Stranka Republike Srpske – SDS) Predrag Kovačević, who emphasized that “BiH could join the EU much faster than it is promoted by politicians from Sarajevo” (Glas Srpske 2007b), and he went even further by stating that “like it or not, RS is a state” (Glas Srpske 2007b). When it became clear that, due to the failure of BiH’s reform efforts, the EU would not (yet) sign the SAA, the speech acts of the RS’s political elite became even more polarizing. Milorad Dodik, for example, stated that “the EU’s decision not to sign the SAA is a consequence of Sarajevo’s intriguing and charlatan policy of unconstitutional centralization of BiH” (Glas Srpske 2007c). Dodik has further securitized the rhetoric by saying that “if anyone wants to abolish RS, we will have the answer,”Footnote 21 and that “they should not put us in a situation where we will have to put this question on the agenda” (RTRS 2007a). By doing this, the extraordinary measures (unconstitutional referendum) were advocated by the securitizing actors in the media landscape for the first time.

The third level of polarization that took place in relation to the “external Other” (international community) was evident both indirectly (as a context for the securitization of the “internal Other”) and directly (the object of securitization – “external Other”). In this respect, the polarization toward the international community began relatively soon, in April 2005, when Dokić – the president of the Socialist Party of RS – said that “there is no progress or development in BiH …, which is why the European Parliament reacted, and with which we got a resolution calling for the changes to the DPA” (RTRS, 2005a). About a month later, the ruling SDS stressed that “nothing special has happened during the SAA negotiations,” and that “negotiations would not have started even if RS had accepted a compromise and started with police reform” (Nezavisne novine 2005b). Glas Srpske (2005c) also reported on this statement to the public, pointing out that the “RS is prepared for the compromise, but the EU must show a greater level of understanding for the interests of Serbs in BiH.” One of the last speech acts of the SDS during its rule was to label the then OHR’s High Representative Paddy Ashdown as someone who “supports failed politicians in power, such as Adnan Terzić,” which is why “they should start discussing the redefinition of both the function and the powers of the OHR” (RTV BN 2006a).

Securitization practices in RS became more visible (Table 2) when the political leadership in this political entity changed. Consequently, in October 2006, Milorad Dodik said that “the SAA is not respected because the decisions about reforms are made by foreigners” and that “they are not sheep led by certain international officers who – because of their own careers – told them what is good and what is not” (Nezavisne novine 2006b, 4). Dodik also emphasized that “if the international community continues making threats, it will not regret if the SAA were not be signed” (Nezavisne novine 2006b, 4). A spiral of polarization and antagonization continued in 2007, when columnist Slavko Mirković – while discussing the so-called three EU principles – argued that these are not “EU’s but Ashdown’s” (Nezavisne novine 2007d, 8). In doing so, Ashdown was framed as a “cynic who failed with police reform and – in line with the demands of the Bosniak political elite – invented some principles” (Nezavisne novine 2007d, 8). A similar rhetoric was utilized by Milan Jelić (president of RS), who argued that “BiH’s constitution does not stipulate that the High Representative could invent reforms in Sarajevo and would then present them in the EU as a precondition for the signing of the SAA” (Glas Srpske 2007d, 5). If the securitization practices of the RS’s political elite indicated that in the context of SAA negotiations, the OHR (and not the EU) is being securitized, this was finally crystallized right before the signing of the SAA. For example, the Bosnian Serb member of the BiH’s presidency, Nebojša Radmanović, stated that BiH “will soon sign the SAA,” and for that reason, it would be “logical to abolish the OHR” (Glas Srpske 2007e, 6). In his statement, Radmanović also emphasized that “if this does not happen, the thesis that there is a certain number of people in Europe who do not want BiH in the EU will be confirmed” (Glas Srpske 2007e). Finally, Dodik, unlike Radmanović, who functioned on the state level (BiH), used a different tactic just before the signing of SAA and promoted the narrative that “he has managed to consolidate the status of RS as a permanent category and equal partner” (Glas Srpske 2007f, 4).

Table 2. Emotionality of Discursive Acts in the Period between 2005 and 2007.

Source: Own analysis.

An important element of the analysis was the possibility of a solution (treatment option) that defines a strategy for tackling a challenge framed as a security threat (Table 3). In the analysis, three strategies prevailed: (1) the institutional solution (48.1%), (2) no solution (35.1%), and (3) compromise/negotiations/cooperation with the other side (10.9%). Here, it should be underscored that the institutional solution is understood in both positive and negative terms when it comes to the reform incentives of the international community. For example, the analysis of the media content between 2005 and April/May 2006 showed that the political elite in RS stressed their cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which was understood as one of the conditions for signing the SAA. For example, Dragan Čavić (SDS) emphasized that “the Peace Implementation Council welcomed the progress of RS in cooperating with the ICTY,” and that “good cooperation with the ICTY is a precondition for a successful European process” (Glas Srpske 2005d, 2; Glas Srpske 2005e, 4). It should also be noted that the consolidation of the narrative of “good cooperation between RS and the ICTY” in this period was ensured by media coverage of the meetings between the political elite of the Republic of Serbia and RS on capturing the war criminals (Nezavisne novine 2005c, 2; RTRS 2005b).

Table 3. Treatment Option in the Period of 2005–2007 (SAA).

Source: Own analysis.

In the period after April/May 2006, when the political leadership in RS was replaced, we recorded speech acts by the political elite that offer an institutional solution in a more negative light. Consequently, the reform efforts by the international community (and the political elite from [F]BiH) were presented by the ruling SNSD as something that “threatens the vital interests of RS” as it “prescribed changes of the DPA.” For example, Dodik started emphasizing that such reform incentives would “destroy the internal structure of the RS” (RTRS 2006b), and that if “reforms go in the direction of establishing state institutions and transferring political power from the level of political entities to the state level, the RS will search for its own solution, with which it will at least maintain its current autonomy” (Glas Srpske 2006c; RTV BN 2006b). However, it should be emphasized that most of the media coverage, where the securitizing actor’s speech acts advocated for the institutional solution, framed the reform efforts aimed at signing the SAA and BiH’s European integration process as something positive and desirable (RTRS 2005c; Glas Srpske 2006c; Nezavisne novine 2006c, 2006d).

A similar logic (positive/negative) as in the case of the institutional solution as a treatment option, is identified when analyzing the speech acts that do not offer a solution to the identified challenge. Consequently, the analysis shows that the period between 2005 and 2006 was marked by more positive speech acts, given that the strategy of not offering any solution envisaged investing efforts in reforms aimed at signing the SAA (e.g., Nezavisne novine 2005f, 3; RTRS 2005d). For example, whereas Milorad Dodik stressed that “RS wants to be a part of the European integration, which is its voluntary and long-defined decision,” Igor Radojičić (SNSD) argued that “everyone in BiH wants European integration and regional cooperation” (Glas Srpske 2006e, 52). In the period after April 2006, the analysis showed a reverse trend, which went in a more negative direction. Milorad Dodik, for example, emphasized that “RS will not accept the abolition of the police and the Ministry of the Interior of RS, even if this means the end of the SAA negotiations” (Glas Srpske 2006e, 3). Dragan Čavić (SDS) went in a similar direction by underscoring that “every historical and administrative category is a result of certain historical circumstances,” which means that “abolition of the RS police structure cannot occur” (Glas Srpske 2006f, 46–47). Finally, the compromise/negotiation/cooperation with the other side as the third most present treatment option showed that such treatment was an option during 2005 and first months of 2006, when RS emphasized the importance of cooperation with the ICTY in order to be subjected to the process of European integration (Nezavisne novine 2005e, 4; RTRS 2005d; RTV BN 2005c).

The content and discourse analysis in relation to the reference to or revival of the past showed that 85.5% of cases were not postulated on the reference to the past (Table 4). However, the largest percentage of securitizing acts, which either referred to the past or attempted to revive it, referred to the Bosnian War (9.3%) In relation to the analyzed period, discourse on cooperation with the ICTY and the issue of extradition of war criminals could be traced. More interesting was that the Bosnian War was the reference to the Kosovo question (4.6%), which we observed in two periods: (1) during the period of BiH’s lawsuit against Serbia and Montenegro for war aggression and genocide, and (2) at the end of 2007, when it became clear that Kosovo would declare independence. During the period of BiH’s lawsuit against Serbia and Montenegro, Kosovo (mainly the war between 1998–1999) was discursively related to cooperation with the ICTY in the context of fulfilling the conditions for the SAA. Speech acts of the RS’s political elite were relatively similar in this respect. For example, Borislav Paravac (SDS) argued that “BiH’s lawsuit is illegal and illegitimate, as it is not backed by the RS and Bosnian Serbs” (Glas Srpske 2005d, 2). During the second period of referencing the Kosovo question, we could observe similar political coherence, except that this time, the political elite from RS linked the Kosovo question with the legitimacy of the OHR in BiH. The most active in that regard was the Bosnian Serb member of the BiH’s presidency, Nebojša Radmanović, who stressed that “the international community is blackmailing BiH,” and that “BiH will not follow the EU’s policy toward Kosovo, because the Kosovo question is understood as Serbia’s internal political matter” (Nezavisne novine 2007g, 3).

Table 4. Reference to the Past or Its Revival in the Period between 2005 and 2007 (SAA).

Source: Own analysis

Finally, when it comes to the equal access to the media and securitizing actors, the analysis showed that the reporting was mostly based on “unbalanced” representation (62.63%), given that the media outlets did not always follow the notion of offering alternative voices. When talking about the securitizing actors, the analysis showed that the most frequently present securitizing actor came from the SNSD “camp” (244). This was followed by the SNSD’s domestic opposition, SDS (46). A more detailed analysis of the above discussed factors (polarization, reference to or revival of the past) showed that the most polarizing actors who have frequently referred to the past were Milorad Dodik (SNSD), Milan Jelić (SNSD), and Dragan Čavić (SDS). For example, the analysis shows that Milorad Dodik polarized during his speech acts in almost 50% of cases, but only 11.6% of his speech acts have emphasized unbridgeable difference between (F)BiH or the international community. In 37.5% of cases, the analysis detected partially polarizing language (moderate criticism). Branko Dokić, a member of the Socialist Party of RS, was much more “securitizing” in his speech acts, but he appeared as a securitizing actor only 15 times, which is why there is such a discrepancy between him and Dodik, who appeared in such a role 112 times.

Conclusion

In this article, we have used securitization theory to understand how and why the securitizing actors in RS in the period between 2005 and 2007, when BiH was negotiating for the SAA, successfully framed the alleged “overall progress, development, and success” deriving from the SAA as a failure and as a mechanism for further division along ethnic lines, instead of something that could potentially mitigate the antagonisms between ethnic groups. By combining content and discourse analysis, we analyzed the grammar of security, the wider discursive context, and the position of power and authority that existed during the period of negotiating the SAA, which have led to successful securitization in RS. The triangulation of both methods has shown that we can talk about two periods within the analyzed period of securitizing acts. The first identified period (from 2005 until April/May of 2006) is marked by a more or less positive context of understanding the SAA as “progress and success,” and the process of European integration as something that would only benefit both BiH and RS. In this period, the overall level of polarization, emotionality, and bias was low. The second identified period (from April/May 2006 until the end of 2007) is marked with a more or less negative context of understanding the SAA, because it was discursively linked by the political elite from RS as something that is inherently linked to (or even derived from) the Bosniak political elite and therefore something that threatens not only the “vital interests of Serbs living in BiH” but also as the “existence of RS.” In this period, the overall level of polarization, emotionality, and bias was medium to high. The content analysis of the “second period” has therefore shown that the political elite from RS used the SAA negotiations to further antagonize both the “internal Other” (Bosniak political elite and [F]BiH) and the “external Other” (predominantly OHR) as a threat to the constitutional order that was laid down by the DPA and that assures the “existence” of subnational political entity of RS. The political elite from RS have also emphasized the need to defend both the constitutional order and the existence of RS through extraordinary measures, such as the unconstitutional referendum.

Furthermore, the content analysis has revealed that there was little reference to the past (mostly they referred to the Bosnian War), which in turn weakened the embeddedness of the threatening grammar into the wider security discourse in RS. This can also be one of the reasons why BiH later ratified the SAA agreement and RS did not accept extraordinary measures, such as the unconstitutional referendum. The analysis also has showed that the context or the general “state of the fear of ceasing to exist” was not discursively linked to the Bosnian War, when such fear was monumental and – through the process of ethnic spatialization – mobilized people along ethnic lines. Consequently, it is also important to note that actors who performed security speech acts had quite good access to the media, where they were not portrayed in a negative light and usually did not have the “alternative voices” to balance their speech acts. The analysis has also further highlighted the analytical added value of the triangulation of content and discourse analysis, because it provided a more nuanced answer to the research puzzle of how the SAA – which is usually portrayed as something “good” and as something that can only bring “progress” to the sociopolitical landscape of the expose potential candidate country – can be framed as an existential threat for the political entity that is exposed to it.

It has therefore showed more comprehensively how the security speech acts of the political elite from RS, which had low success when addressing the final outcome of the analyzed process (SAA negotiations), have been successfully promoted and even sustained for years to come. For example, certain security narratives (e.g., the reform efforts by the Bosniak political elite and the international community are unconstitutional – against DPA) that underpinned the wider discursive context and consolidated the power and authority of Milorad Dodik and his SNSD during this process still exist today and have successfully managed to prevent any meaningful reforms by the international community in general and the EU in particular. Here – although our analysis has focused on the 2005–2007 SAA negotiation process – we are referring to the Prud and Butmir processes between 2008 and 2009 that were unsuccessful and were underpinned with similar discursive context, similar securitizing actors, and similar security grammar (security speech acts). The discourse of the political elite from RS during the SAA negotiations therefore reflects on a broader phenomenon regarding both the negotiations for the EU and European integration. One could argue that members of the political elite perceive and/or frame European integration as “existential uncertainty” for the future of RS. By avoiding such existential uncertainty with the strategy of preserving the status quo and using securitization as a technique of governance, they inevitably contribute to the consolidation of the narrative within the sociopolitical landscape of RS that European integration could potentially signal the end of the political capabilities of RS and the existence of RS.

However, our analysis comes with one important warning. It has focused exclusively on the positional power and wider security context in RS, which is one of the two subnational political entities in BiH. In this regard, the positional power of RS vis-à-vis both FBiH and BiH is still underexplored within this empirical puzzle. If we wanted to consider the actual weight of RS’s political elite security speech acts or even pursue the “action-reaction paradigm” in relation with the security speech acts that came in the same period from FBiH, then we would need to broaden our content and discourse analysis by adding the most important media outlets that are widely disseminated primarily in FBiH. Here, it has to be noted that the predominant perception that underpins the relations between the Bosniak and Bosnian Serb political elite is that the EU, through different mechanisms (e.g., financing grassroots projects), “favors the unconstitutional narrative,” which in turn attempts at imagining the civic identity (Bosnian and Herzegovinian) and therefore favors Bosniaks because they are the only ones who can identify with the state level. This can also be a part of the explanation of why the securitizing acts in RS were successful in facilitating “sticky” security narratives (Miskimmon and O’Loughlin Reference Miskimmon and O’Loughlin2019). These and other approaches could therefore be used in future studies to capture aspects of the 2005–2007 SAA negotiation that were uncovered in this analysis but that are important when trying to understand the contemporary deadlock in relation to the European integration process.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency under Grant P5-0177 (research programme “Slovenia and its actors in international relations and European integrations”).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ana Bojinović Fenko, Mitja Velikonja, Rok Zupančič, and the two anonymous reviewers, who helped him improve the article with their valuable comments.