Introduction

In 1888 ce (1306 ah), Ibrahim Nooraddeen became the Sultan of the Maldives for the second time. In that year, he banished into exile the highest member of the judicial branch—the chief justice.Footnote 1 The chief justice was a Maldivian poet and scholar of Arabic. His full name was Shaykh Muḥammad Jamāluddīn ibn an-Nā’ibu ‘Īsa al-Mulakī (circa 1844–1907). Maldivians commonly refer to him as ‘Naibu Thuhthu’, which will be used henceforth in this article.Footnote 2 Naibu means ‘judge’. Thuhthu is a term of endearment that literally means ‘little’.Footnote 3 For the next three years in exile, Naibu Thuhthu was forced to reside on the northern island of Fehendhoo, located on Southern Maalhosmadulu (Baa) Atoll.

Exiled in Fehendhoo, Naibu Thuhthu devoted himself to scholarly and artistic pursuits that intertwined the description of language with the composition of poetry.Footnote 4 Over the years Naibu Thuhthu spent in Fehendhoo, the year 1890 was particularly productive. In that year, he wrote one of the earliest linguistic descriptions of the Dhivehi language.Footnote 5 In 1930, Athireegey Ahmed Dhoshimeynaa Kilegefaan printed the study through a printing press in the Maldives known as the Maṭbā‘a al-Amīrī al-Maḥaldībī.Footnote 6 The title of the essay was ‘Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id’ (The Manner of Writing Thaana, 1890).Footnote 7 In ‘Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id’, Naibu Thuhthu described facets of the Dhivehi language, made linguistic prescriptions, and used Dhivehi poetry as evidence of correct usage.

While in Fehendhoo in 1890 Naibu Thuhthu also fashioned a Dhivehi poem with the Arabic title, ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’ (Correct Language).Footnote 8 It presented grammatical concepts of Arabic linguistic theory, and it stressed that poets and readers needed to understand these Arabic concepts to write and comprehend Dhivehi poetry. In order to write this poem Naibu Thuhthu seems to have studied Arabic linguistic theory either directly from or via commentaries on a widely circulated thirteenth-century grammar of the Arabic language written by Ibn Ājurrūm (d. 1223) entitled al-Ājurrūmīyya.

The title of this article—‘Poetry for Linguistic Description’—thus has two connotations. First, it refers to Naibu Thuhthu's use of poetry as source material for linguistic description and, second, to Naibu Thuhthu's utilization of linguistic description as a topic for poetry.

Inside and outside the Arabic cosmopolis

Why should the readers of Modern Asian Studies care about the Dhivehi-language poetry and linguistic description in the two abovementioned sources? I suggest two reasons: the first is that the analysis of Naibu Thuhthu's poetic references to the thirteenth-century grammar of the Arabic language, al-Ājurrūmīyya, enriches discussion in Asian studies regarding the cultivation of erudition in the Indian Ocean through the study of Arabic.

‘The study of Arabic was the beginning of all wisdom’, noted the Dutch philologist of Javanese and Malay G. W. J. Drewes in 1970 with regard to Indonesia.Footnote 9 Drewes conducted archival research at the National Library of Indonesia and the Leiden University Library to understand which Arabic grammars were studied by Javanese and Malay speakers between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although he did not attempt to historize the usage of certain Arabic grammars, he did ultimately single out the grammar al-Ājurrūmīyya, along with another thirteenth-century grammar of Arabic entitled Alfiyya by Ibn Mālik al-Ṭa'I (d. 1274), as the two ‘most widely spread works on [Arabic] grammar [in Indonesia]’.Footnote 10

One must note here that al-Ājurūmīyya and Alfiyya not only circulated from the Middle East eastwards to Indonesia, they were also in high demand as far west as Islamic West Africa. Bruce Hall and Charles C. Stewart examined copies of Arabic manuscripts that appeared in the largest numbers of representative libraries from the Atlantic to northern Nigeria to determine the Arabic texts that were used heavily in Islamic West Africa. They singled out al-Ājurrūmīyya and Alfiyya as ‘the two most widely used works of syntax in West Africa’.Footnote 11

References to the al-Ājurrūmīyya in the Maldives in Naibu Thuhthu's 1890 Dhivehi-language poem not only demonstrates that Arabic grammars and commentaries on these grammars were as important for the cultivation of wisdom in the Maldives as in Indonesia and West Africa, they also serve as a reminder of the Maldives’ role as an Indian Oceanic link connecting the Middle East with Southeast Asia. A. C. S. Peacock explored how in the 1500s and 1600s one chief factor to bolster the Maldivian link between the Middle East and Southeast Asia were Sufi networks, which were marked not by an openness to diversity but rather by an attempt to ‘impose unity over diversity’.Footnote 12 Peacock analysed excerpts in Ḥasan Tāj al-Din's Arabic-language history of the Maldives in which Tāj al-Din described the travels and impact of Sufi shaykh Sayyid Muḥammad Shams al-Dīn. Born in Syria, Shams al-Dīn came under the direction of the descendants of the founder of the Sufi Qādiriyya order (ṭarīqa), ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī. He later studied at the centre for Arabic learning, al-Azhar, in Cairo. Shams al-Dīn travelled to Yemen, the Coromandel coast of India, and then arrived in Aceh, Sumatra, where was royally received by Acehnese elites. There, according to Tāj al-Din, Shams al-Dīn began to successfully forbid cultural practices that he deemed anti-shari'a. In 1686, he sailed to Malé, where he was warmly received by the Maldivian Sultan Ibrāhīm Iskandar, and again was encouraged to enforce a stricter adherence to Islamic law and a rejection of local customs. It appears that both the Acehnese nobles and the Maldivian sultan sought to legitimate their authority by encouraging Shams al-Dīn to make sharī’a-based religious proscriptions.

In the case of Naibu Thuhthu's two forms of ‘poetry for linguistic description’, the large process that comes to the fore is not Sufic Islamization in the Indian Ocean but rather the circulation of Arabic language and literature in the region. This brings me to the second reason why readers of Modern Asian Studies might take note of Naibu Thuhthu's Dhivehi-language poetry and linguistic description: these sources can provide new perspectives on vernacular languages and literatures within what Sheldon Pollock described as the ‘Sanskrit cosmopolis’, what Ronit Ricci termed the ‘Arabic cosmopolis’, and what Richard Eaton designated as the ‘Persian cosmopolis’.Footnote 13

Pollock coined the term ‘cosmopolis’ to refer to the Sanskrit language's supra-regional (‘cosmo’) spread across South and Southeast Asia between 400 and 1400, its prominent political dimension (‘-polis’), and the primary role of this particular language in influencing expressive culture in South and Southeast Asia.Footnote 14 Ricci analysed how one Arabic-language text, the Book of One Thousand Questions, was translated into Javanese, Tamil, and Malay.Footnote 15 In response to Pollock, she coined the term ‘Arabic cosmopolis’ and defined it as ‘a translocal Islamic sphere constituted and defined by language, literature, and religion’.Footnote 16 Richard Eaton introduced the term ‘Persian cosmopolis’ to refer to the transregional spread of the Persian language, as well as Persian ideas, values, and aesthetic sensibility between 900 and 1900 via texts like dictionaries and poems as well as material culture.Footnote 17

The ‘cosmopolis scholarship’ of Pollock, Ricci, and Eaton tells a narrative about how the wide circulation of Sanskrit and Arabic throughout South and Southeast Asia, and Persian literature throughout West, Central, and South Asia fostered a commensurably vast network of writers who, under the influence of Sanskrit, Arabic, and/or Persian, authored texts in major vernacular languages like Bengali, Burmese, Javanese, Kannada, Khmer, Malay, Sinhala, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, and Tibetan. This scholarship suggests that authors living within the Sanskrit, Arabic, or Persian cosmopolis wrote in divergent vernacular languages, but nonetheless were connected in some sense because they translated and responded creatively to Sanskrit, Arabic, and/or Persian literary forms.

Ricci, for example, suggested that ‘as the cross-regional use of untranslated Arabic terms [in Javanese, Tamil, and Malay translations] gave rise to a shared religious vocabulary, so the use of a common script across cultural and geographical distance contributed to the consolidation of an orthographically unified community’.Footnote 18 Similarly Pollock emphasized that Sanskrit forms of knowledge connected literati throughout South and Southeast Asia:

Just as the kāvyas were studied everywhere throughout this domain, so were the texts of literary art (alankāraśastra), metrics, lexicography, and related knowledge systems. Not only did these texts circulate throughout the cosmopolis with something like the status of precious cultural commodities; they came to provide a general framework within which a whole range of vernacular literary practices could be theorized …The vernacular intellectuals of southern India, Thailand, Cambodia, Java, and Bali took in Sanskrit metrics in a gulp, as they did Sanskrit lexicography.Footnote 19

When one reads these statements by Pollock and Ricci one may begin to feel that writers who lived across vast distances in Asia became ‘connected’ through their mutual contact with cosmopolitan languages of Sanskrit or Arabic. Yet in cosmopolis scholars’ effort to reveal understudied connections, they tend to overlook various degrees of disconnection among writers of vernacular languages within a cosmopolis. One problem of overlooking disconnection among writers of vernacular languages is that readers could mistakenly conflate superculture-subculture interaction with intercultural interaction.Footnote 20

Allow me to first discuss superculture-subculture interaction before I turn to the issue of intercultural interaction. At the level of superculture-subculture interaction, one could persuasively argue, as Ricci has done, that the Muslim speakers of Tamil, Javanese, and Malay were, in Ricci's words, an ‘orthographically unified community’ due to their shared entanglement with the overarching dominant system of Arabic. In Drewes’ article ‘The Study of Arabic Grammar in Indonesia’, he described how Malay and Javanese scholars often left Arabic technical terms untranslated in commentaries on and translations of Arabic texts and, over time, such terminology became integrated into the lexicons of Malay and Javanese.Footnote 21 Ricci, for example, noted how a key feature in Malay-language texts of One Thousand Questions is the frequent use of Arabic in lexicons, citations from the Quran, and conventional phrases of praise.Footnote 22

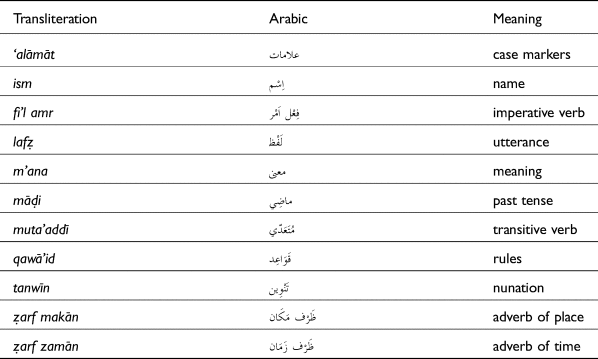

Similarly, in the Maldives, Naibu Thuhthu wrote primarily in the Dhivehi script Thaana, but when he required a more technical term for linguistic description, he selected terms that he knew from his study of Arabic. Naibu Thuhthu had studied Arabic with teachers in the Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Saudi Arabia.Footnote 23 To give the reader a sense of Naibu Thuhthu's usage of Arabic, Table 1 lists 11 Arabic terms Naibu Thuhthu wrote in the Arabic script for his description of the Dhivehi language in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id:Footnote 24

Table 1. Arabic terms found in Naibu Thuhthu's Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id (1890).

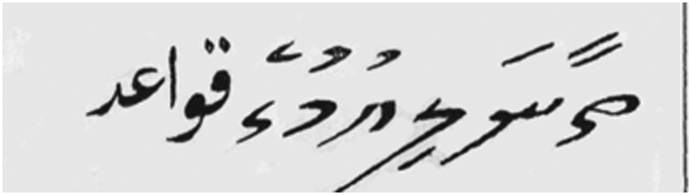

It is possible to broadly conceive of this issue through the lens of ‘digraphia’,Footnote 25 which refers to ‘the employment of two (or more) writing systems to represent varieties of a single language’.Footnote 26 One finds digraphia even in the title of his linguistic description—Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id (The Manner of Writing Thaana) (see Figure 1).Footnote 27 Note how Naibu Thuhthu employed two Dhivehi-language terms: Thaana (ތާނަ) is the name of the script used for the Dhivehi language and liumuge (ލިއުމުގެ) literally means ‘of writing’. The third term, qawā‘id (قواعد) (lit. ‘rules’) is Arabic, and it appeared in the Arabic script.

Figure 1. Digraphia in the title of Naibu Thuhthu's 1890 essay.

Naibu Thuhthu had cultivated his knowledge of Arabic with Arabic teachers in the Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Arabia.Footnote 28 Indeed, it is highly likely that his very impulse to utilize Dhivehi poetry as source material for the linguistic description of the Dhivehi language stemmed from his familiarity with the approach of Arabic grammarians from the first to the seventh centuries who, in Michael Zwettler's words, attached ‘primary importance to the evidential value of poetry for determining “correct” usage’.Footnote 29 Likewise, it is distinctly possible that Naibu Thuhthu's idea to compose poetry about Arabic grammatical categories stemmed from his familiarity with Arabic grammarians who wrote their grammars through the medium of verse, such as the widely circulated Arabic long poem in rajaz meter entitled Mulḥat al-iʿrāb fī al-naḥw composed by Al-Ḥarīrī of Basra (1054–1122).Footnote 30

However, at the level of intercultural interaction among writers of vernacular languages the situation in the Arabic cosmopolis may have been marked with unacknowledged forms of isolation. For example, one could argue that the Tamil translators of One Thousand Questions were disconnected from the Malay/Javanese translators of the same text because in the 1700s, when individuals were creating Malay-language and Javanese-language translations of this text, they had no knowledge of Vaṇṇapparimaḷappluluvar's Tamil-language One Thousand Questions, which he authored in the 1500s.Footnote 31

I am not suggesting that there was no intercultural interaction. For example, scholars have noted that Javanese and Malay authors, translators, and scribes are likely to have engaged in dialogue in some ways. Because the Prophet's son-in-law Ali is regularly featured in Javanese-language texts of One Thousand Questions, G. F. Pijper argued that the mention of Ali in a Malay One Thousand Questions meant that this work was based on a Javanese text.Footnote 32 Pijper found further evidence for Javanese-Malay interaction in the way the name of the Jewish scholar in a Malay One Thousand Questions was written: the name was ‘Samud ibnu/ibni Salam’ or simply as ‘Samud’, which followed Javanese practice.Footnote 33 E. Wieringa further argued that the Malay text's orthographic features pointed to Javanese origins.Footnote 34 Ricci noted how the Palembang Sultanate in eastern Sumatra was a ‘meeting place for Malay and Javanese cultures’.Footnote 35 She further notes that the sultanate's library holds both Malay and Javanese manuscripts, and that Javanese was the official court language.Footnote 36

Regarding the Maldives, it is important to note that at the level of intercultural interaction, no written documents exist to suggest that in circa 1890 Malays, Javanese, Tamils, and other ethnicities within the Arabic cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia could even read the Thaana script of the Dhivehi language. If the vast universe of non-Maldivians in the Arabic cosmopolis of South Asia and Southeast Asia could not read the Dhivehi script, then one begins to feel differently about Ricci's notion of an ‘orthographically unified community’.Footnote 37

I would thus like to suggest here that the emphasis on connection in research in cosmopolis studies must at least be tempered with the acknowledgment of contemporaneous types of isolation and disconnection among vernacular languages and literatures. In this article, I characterize the relationship between the Maldives and the Arabic cosmopolis as a ‘disconnected connection’. I argue that Dhivehi-language poetry and linguistic description were not only ‘inside’ the Arabic cosmopolis because it was influenced by Arabic texts, but ‘outside’ as well because non-Maldivians living within the Arabic cosmopolis could not even read Naibu Thuhthu's two forms of poetry for linguistic description.

To my knowledge, between 1841 and 1901 the only non-Maldivians who had a basic knowledge of Dhivehi were a handful of Western civil servants, missionaries, and Orientalists. What these men did was either compile a list of words based on speech or collect documents and ask a Maldivian to assist them in a word-for-word translation. There is no evidence to suggest that these men could fluently read or converse in Dhivehi. For example, in 1841 the Scottish missionary Reverend John Wilson published a vocabulary of Dhivehi terms that was originally compiled by W. Christopher, a British lieutenant of the Royal Indian Navy, who had visited the Maldives in 1834. In 1878, a British civil servant named Albert Gray published another vocabulary based on the lexicon originally compiled by French navigator François Pyrard de Laval when de Laval lived in the Maldives between 1602 and 1607. In 1883, the archaeological commissioner for Ceylon H. C. P. Bell discussed the Dhivehi language in his monograph The Maldive Islands: An Account of the Physical Features, Climate, History, Inhabitants, Productions, and Trade. Finally, between 1900 and 1902 the German Orientalist, Wilhelm Geiger, published etymological studies of Dhivehi.Footnote 38

Having explained what I mean by ‘outside’ the Arabic cosmopolis, I now devote the rest of the article to exploring how the two aforementioned texts written in 1890 by Naibu Thuhthu were inside the Arabic cosmopolis. Before I proceed, one explanatory note is in order. Although this article focuses on the writings of Naibu Thuhthu's ‘poetry for linguistic description’, readers should not assume that his fusion of poetry and linguistics was an anomaly in the Maldives. Two intellectuals of the next generation approached verse and linguistics in similar ways. In 1928, Naibu Thuhthu's arguably most influential student Hussein Salahuddin (1881–1942) completed a new linguistic study of the Dhivehi language. He bestowed on the study the Arabic title al-Tuḥfat al-Adabiyyatu li-Ṭullāb il-Lughat il-Maḥaldībiyyati (The Literary Gift for Students of the Maldivian Language).Footnote 39 In this study, Salahuddin, like his teacher Naibu Thuhthu, used Dhivehi poetry as part of his linguistic corpus.Footnote 40 Then in 1936, the Maldivian scholar Sheikh Ibrahim Rushdee al-Azharee (d. 1961) published a linguistic description of Dhivehi entitled Sullam al-Ārīb fi Qawā‘id Lughati al-Mahaldību (The Ladder for the Intelligent Student for Learning the Grammar of the Maldivian Language).Footnote 41 In this study, Sheikh Ibrahim followed in the footsteps of Naibu Thuhthu and Salahuddin: he too used Dhivehi poetry to make observations about Dhivehi grammar.Footnote 42 Finally, in 1946, Salahuddin, like his teacher Naibu Thuhthu, published a poem entitled ‘Bas’ (Language), which discussed grammatical concepts within the framework of poetry.Footnote 43

Poetry for linguistic description 1

Poetry for the linguistic description of a vowel

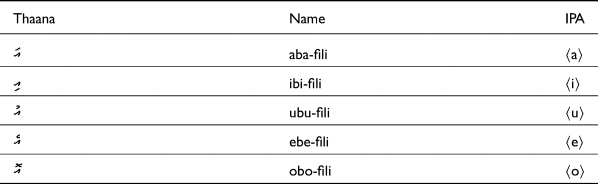

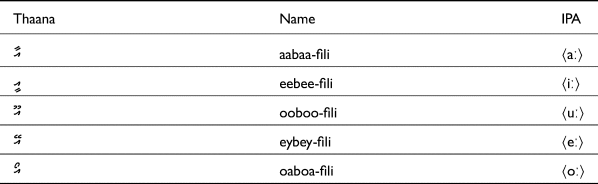

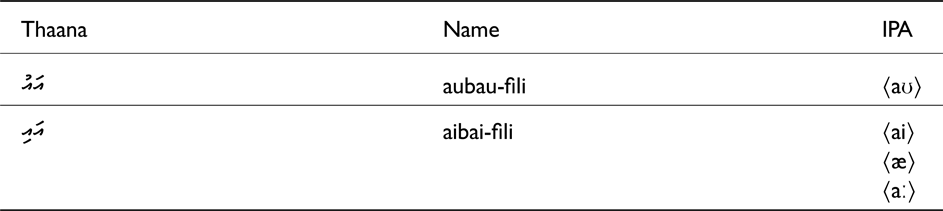

The first reason why Naibu Thuhthu analysed Dhivehi poetry in his essay Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id was to substantiate linguistic prescriptions pertaining to the proper use of a vowel known in Dhivehi as aibai-fili. To become oriented with the vowels of the Dhivehi language, consider Tables 2, 3, and 4. They depict the Thaana letters for the short vowels (see Table 2), long vowels (see Table 3), and vowel sounds created through the combination of two vowels, that is, diphthongs (see Table 4). In each table, the second column provides the Dhivehi-language name of each letter, and the third column lists each letter's International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbol.

Table 2. Short vowels.

Table 3. Long vowels.

Table 4. Diphthongs.

Consider the final vowel listed, the aibai-fili. Note that it is a diphthong because it is a sound created through the combination of two vowels. Note too that because aibai-fili is written with the combination of two letters we can consider it a ‘digraph’. Specifically, the letter އަ ⟨a⟩ combines with the letter އި ⟨i⟩ to produce the digraph of އައި (Thaana is written from right to left like Arabic). Further, and most importantly, due to Dhivehi dialects, this letter is pronounced in three ways. In Malé, the capital of the Maldives, the vowel is usually pronounced as ⟨æː⟩. In the north, it is pronounced as ⟨aː⟩. In the southern islands aibai-fili pronounced as ⟨ai⟩.Footnote 44

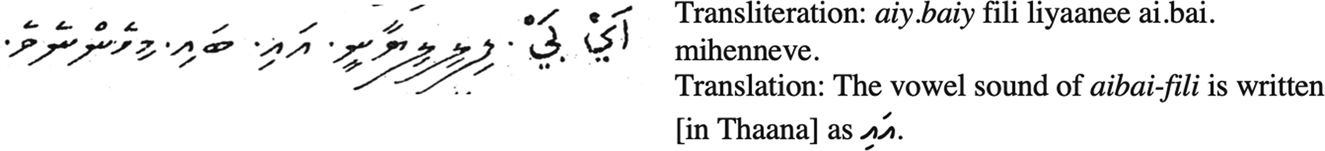

When Naibu Thuhthu discussed the aibai-fili vowel he articulated both implicit and explicit mindsets about the Dhivehi language. Linguistic anthropologists call such mindsets ‘language ideologies’, that is, ideas and attitudes people express about language.Footnote 45 Regarding the implicit idea, to convey the linguistic sound of the vowel aibai-fili Naibu Thuhthu spelled ‘aibai-fili’ with Arabic letters—‘اَيْ،بَيْ ’. One may conjecture that for Naibu Thuhthu the Arabic script was a more scientific code, like today's IPA. In other words, it can be suggested that Naibu Thuhthu believed that the Arabic script could help him describe more empirically the linguistic sound of the vowel aibai-fili.Footnote 46 Figure 2 is an image of the sentence where Naibu Thuhthu used Arabic to name the phonetic sound of aibai-fili. Next to the figure is a transliteration followed by a translation.

Figure 2. Jamālluddīn, Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id, p. 4.

Naibu Thuhthu also articulated more explicit language ideologies. Maldivians, Naibu Thuhthu suggested, had become accustomed to pronouncing the aibai-fili vowel as a ‘long aa’—⟨aː⟩.Footnote 47 He claimed that writing and speaking aibai-fili in this way was ‘unpleasant’, and he further suggested that ‘a person who knows the grammar of the Dhivehi language can write and speak without confusing these two vowels’.Footnote 48 In this sentence, when Naibu Thuhthu employed the word ‘grammar’ he not only selected the Arabic term naḥw but he also defined this term for his readers as: ‘the name given in the Arabic language to the ways of knowing the rules and principles of speaking in any language’.Footnote 49

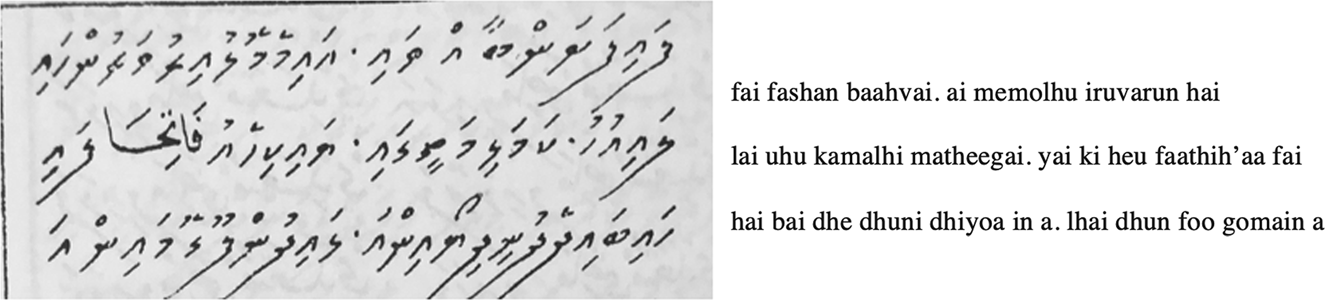

Having discussed improper use of aibai-fili, Naibu Thuhthu set out to illustrate the proper usage. The source he selected for his linguistic prescription was a verse of poetry composed in a genre of Dhivehi sung poetry known as raivaru. Specifically, it was the fiftieth stanza from the Dhivehi poem entitled Dhiyoage Raivaru (The Raivaru of the Beautiful Woman, circa 1800), a long poem of 331 stanzas.Footnote 50 Figure 3 presents an image of the poem as it appeared in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id. To the right of the figure is a transliteration. Although the verse customarily appeared in continuous script (no spaces) I have transliterated it with spaces to indicate how Maldivian readers would automatically parse the intact words and scrambled syllables.

Figure 3. Naibu Thuhthu's citation of the fiftieth verse from Dhiyoage Raivaru: Jamālluddīn, Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id, p. 5.

Naibu Thuhthu authored just one terse sentence to explain why this verse was significant for its proper usage of the aibai-fili vowel: ‘The words at the beginning and end of [lines 1 to 4] are recited with aibai-fili.’Footnote 51 Further, Naibu Thuhthu did not unscramble the syllables of the verse for his readers. By the mid-twentieth century it had become common for scholars of raivaru to unscramble verses for their readers because the raivaru genre and its unique trait of syllable scrambling had fallen out of usage. Writing in 1890, Naibu Thuhthu must have assumed that his readers did not need an explanation of how the syllables in this verse should be unscrambled.

Why did he point out that the words at the beginning and end of lines 1 to 4 were recited with aibai-fili? To answer this question, one must first translate the stanza and understand the syllable scrambling involved. Table 5 organizes the verse as it would usually appear in print: a six-line stanza with each poetic foot comprising one line.Footnote 52 The aibai-fili vowels are bolded in lines one to four. The verse portrays the younger sister from Mozambique (see footnote 50) and her entourage performing a keel laying ceremony to recognize the commencement of the construction of their fleet of ships.

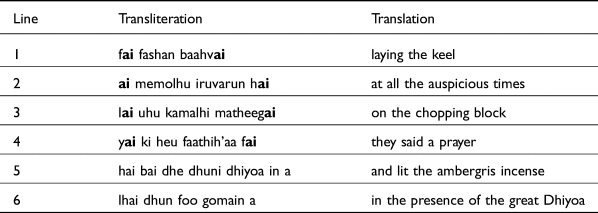

Table 5. Verse 50 in Dhiyoage Raivaru and translation.

Readers of the transliteration in Table 5 can see the aibai-fili vowels in bold at the beginning and end of lines one to four. This is precisely what Naibu Thuhthu was referring to when he wrote, ‘The words at the beginning and end of [lines 1 to 4] are recited with aibai-fili.’Footnote 53

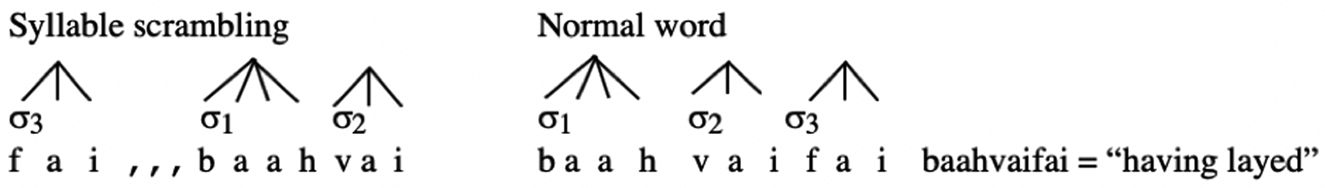

Before considering why Naibu Thuhthu presented this verse of poetry in his essay about linguistic description, it will be instructive also to grasp the syllable scrambling involved. Allow me to explain one instance of syllable scrambling. Let us consider line 1. Figure 4 attempts to explain how the syllables of one word in line 1 were scrambled. The figure follows common practice in the discipline of phonology to represent the syllable with the lowercase Greek symbol sigma ‘σ’. Notice the superscript numerals next to the sigmas. The numerals indicate the order of syllables in the regular word. Thus, to unscramble the line, the listeners would have known that the first syllable in the line of poetry—fai—is really the final syllable in the conjunctive verb baahvaifai (having layed). The three commas (,,,) represent the three-syllable word fashan (keel), which appeared intact in the verse. I use these commas to abstractly represent the word fashan to focus the mind of the reader on the syllable scrambling.

Figure 4. Diagram illustrating the use of syllable scrambling and the normal word in verse 50, line 1 of Dhiyoage Raivaru.

It is clear that Naibu Thuhthu found it significant that the poet used the aibai-fili vowel at the beginning and end of lines 1 to 4. But what would have been the incorrect alternative? To answer this question, it will be instructive to read a commentary about this stanza written by scholar Abdulla Saadiq. Like Naibu Thuhthu, Saadiq highlighted the way in which the author of this stanza used aibai-fili:

Next I will present an example of how Manikufaanu, the author of Dhiyoage Raivaru, employed aibai-fili. Some teachers of Dhivehi say that if a word has adjacent aibai-fili vowels then one of the aibai-fili vowels should be made into an aabaa-fili…The good Hasan Ban'deyri Manikufaanu tells us [through his fiftieth verse] that aibai-fili [rather than aabaa-fili] should come in each place.Footnote 54

Saadiq discussed words that have ‘adjacent’ aibai-fili vowels. In Dhivehi, the class of verbs that regularly contains adjacent aibai-fili vowels are the conjunctive verbs, sometimes referred to as ‘converbs’, ‘absolutives’, or ‘conjunctive participles’. Conjunctive verbs are often translated into English as ‘having told’, ‘having eaten’, etc. because conjunctive verbs make explicit that the action of the conjunctive verb precedes the action of the main verb.Footnote 55 For the purpose of this article one must understand the concept of the conjunctive verb because two of these verbs appear in the fiftieth stanza: baahvaifai (having laid) and kiyaifai (having recited). Consider how these words have adjacent aibai-fili vowels (bolded here): baahvaifai and kiyaifai (having recited).

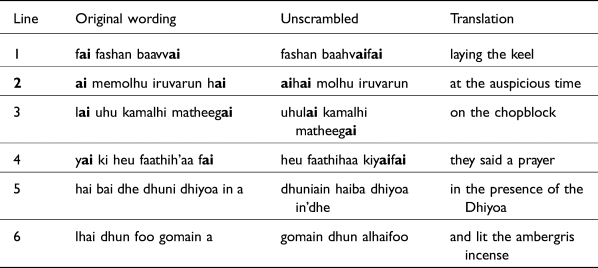

Saadiq then unscrambled the syllables and put the words of each line into normal syntax, which I have presented in Table 6 along with a translation.

Table 6. The fiftieth stanza of Dhiyoage Raivaru, original, unscrambled, translated (adapted from Saadiq, Ban'deyri H'asanmanikufaanuge Dhiyoa Lhen, p. 17).

Consider the unscrambled version of line 1. Notice specifically how the line changed when Saadiq unscrambled the syllables and placed the two words in normal syntax: from fai fashan baavvai to fashan (the keel) baahvaifai (having layed).

Having presented the unscrambled version of this stanza, Saadiq explained to his readers what the incorrect alternative would have been regarding the spelling of adjacent aibai-fili vowels. The incorrect alternative would have been to use aabaa-fili—⟨aː⟩. As I explained, the letter aibai-fili can be pronounced in three ways. In Malé it is often pronounced as an aabaa-fili. This is precisely the spelling and pronunciation that Naibu Thuhthu described as ‘unpleasant’. Naibu Thuhthu in 1890 (and Saadiq in 2007) believed that the fiftieth verse of Dhiyoage Raivaru offered proof that the correct way to spell, and maybe speak too, was to employ two adjacent aibai-fili vowels rather than aabaa-fili vowels. To drive home this point Saadiq presented to the reader the rearranged verse as correct and incorrect prose. In the correct sentence he spelled with aibai-fili. In the incorrect sentence he spelled with aabaa-fili:

Ban'deyri Hasan Manikufaanu has written, aihai molhu iruvarun fashan baahvaifai kamalhi matheegaa uhulai heyo faathih'aa kiyaifai dhuniyein haiba dhiyoa gomain dhun alhaifieve

Ban'deyri Hasan Manikufaanu did not write, aihaa molhu iruvarun, fashan bahvaafai kamalhi matheegai uhulai heyo faathihaa kiyaafai, etc.Footnote 56

Saadiq's point, I am convinced, is precisely what Naibu Thuhthu in 1890 sought to express when he wrote the sentence, ‘The words at the beginning and end of [lines 1 to 4] are recited with aibai-fili.'Footnote 57 In the next sub-section I explore one more example of how Naibu Thuhthu utilized poetry for linguistic description in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id.

Poetry for the linguistic description of a diacritic

The second reason why Naibu Thuhthu analysed Dhivehi poetry in his essay Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id was to authenticate his linguistic recommendations regarding the diacritic known as the sukun. ‘Diacritic’ means a sign written above or below a letter to indicate that the letter should be pronounced in a different way. The Dhivehi term sukun comes from the Arabic-language term sukūn (سُكُون ). In both writing systems the sukun is a small mark in the shape of a circle which is placed on top of consonants that do not carry a vowel.

In Dhivehi words, the sukun appears only on syllable-final consonants, which are sometimes referred to in phonology as ‘coda consonants’.Footnote 58 For example, consider the final bolded consonants in these hypothetical syllabic structures in which ‘V’ means vowel and ‘C’ means consonant—VC, CVC, CVVC, and VCC. In Dhivehi, the final bolded consonants would be letters marked with a sukun.

The Dhivehi sukun, however, is a more complex phenomenon for three reasons, which I introduce now but explore in more detail below. First, there are restrictions on the number of letters that can carry sukun. Maldivians thus learn acronyms to remember the letters that can carry the sukun. Second, the sukun is a more complex phenomenon due to the way it is used to spell doubled consonants. Third, when four letters follow the sukun it triggers nasalization. Maldivians learn a second acronym, explained below, to remember these four letters. Given these issues, it is no surprise that Naibu Thuhthu and later grammarians of Dhivehi sought to bring order to this thorny issue.

In Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id, Naibu Thuhthu began his discussion of the sukun with an explanation of the restrictions on letters that can carry the sukun: ‘In every dialect spoken north of the Huvadhu channel the sukun can be carried by four letters. These four letters are “uni thoshi” or “thoonu oshi”.’Footnote 59 Naibu Thuhthu's linguistic description was space-contingent: the Huvadhu channel is the waterway that separates the northern and southern atolls, two regions that are home to major dialect differences.Footnote 60 The terms uni thoshi and thoonu oshi function as acronyms, but they do have literal meanings, which are albeit arbitrary.Footnote 61

The terms uni thoshi and thoonu oshi were devices Maldivians memorized to remember the letters that the Dhivehi sukun could carry: the four letters of u-ni-tho-shi represented the four letters abafili (އ), noonu (ނ), thaa (ތ), and shaviyani (ށ). Likewise, the four letters of thoo-nu-o-shi represented the same letters in a different order: thaa (ތ), noonu (ނ), alifu (އ), and shaviyani (ށ). When these letters carry a sukun, the names of the letters are: thaa sukun, noonu sukun, alifu sukun, and shaviyani sukun.

Naibu Thuhthu's thoughts on the sukun and his discussion of the sukun in poetry can be understood if one has knowledge of additional linguistic information, which I explain in the following paragraphs. Students of Dhivehi not only learn that the four letters thaa (ތ), noonu (ނ), alifu (އ), and shaviyani (ށ) carry the sukun, they also learn that when these four letters carry the sukun there is an impact on two additional linguistic realms: spelling and pronunciation.

Regarding spelling, Dhivehi linguist Amalia Gnanadesikan has noted that, ‘Thaana orthography is unusual in having explicit markers of gemination rather than specifically doubling each letter (or leaving gemination unmarked) as most other scripts do.’Footnote 62 ‘Gemination’ in phonetics refers to the phenomenon when consonants are doubled and pronounced for a longer period of time than a short consonant. Gnanadesikan is saying that when Dhivehi consonant are doubled (that is, ‘dd’, ‘gg’, ‘bb’, etc.), the particular consonant is not written twice (as I have done in the previous parentheses). Rather, there are only certain letters that can serve as the initial consonant of the double. That is what Gnanadesikan means by the term ‘marker of gemination’.

What letters can serve as this marker of gemination? In Dhivehi, the letter that primarily serves as the marker of gemination is alifu sukun (އް). Thus, when one spells the standard word for ‘father’—bappa—the first geminate consonant is not written with /p/—(ބަ+ޕް+ޕަ) but rather with alifu sukun (ބަ+އް+ޕަ).

However, the issue is more complex because in certain words two different letters can serve as the marker of gemination: shaviyani sukun and noonu sukun. For example, the geminate consonant in the word for ‘eighth’—avvana—is spelled not with alifu sukun but rather with the shaviyani sukun (އަ+ށް+ވަ+ނަ), and the geminate consonant in the word emme (all) should be spelled not with alifu sukun but rather with noonu sukun (އެ+ން+މެ).Footnote 63

Given the Maldives’ location within the Arabic cosmopolis and Naibu Thuhthu's training in Arabic, it should not surprise the reader that when Naibu Thuhthu described the behaviour of the geminating sukun he explained this phenomenon with a related concept in Arabic linguistic theory: the tashdīd. Naibu Thuhthu wrote, ‘… even when the four letters [abafili (އ), noonu (ނ), thaa (ތ), and shaviyani (ށ)] carry a sukun one does not understand that it is a sukun because shaviyani sukun and alifu sukun are pronounced with tashdīd’.Footnote 64 Tashdīd refers to the placement of an Arabic diacritic known as the shadda ![]() on top of Arabic letters to indicate gemination of consonants. Naibu Thuthu's point was that when a sukun is placed on shaviyani sukun or alifu sukun, the shaviyani sukun is not pronounced as ‘sh’ ⟨ʂ⟩ and the alifu sukun is not pronounced as ⟨ʔ⟩. Instead, both transform into the geminate consonant.

on top of Arabic letters to indicate gemination of consonants. Naibu Thuthu's point was that when a sukun is placed on shaviyani sukun or alifu sukun, the shaviyani sukun is not pronounced as ‘sh’ ⟨ʂ⟩ and the alifu sukun is not pronounced as ⟨ʔ⟩. Instead, both transform into the geminate consonant.

In addition to spelling, the sukun also has an impact on pronunciation. When the alifu sukun and shaviyani sukun appear at the end of a word they are both pronounced as a glottal stop ⟨ʔ⟩, which is the consonant created by release of the airstream when one closes the glottis (as in the sound of the term ‘uh-’ in ‘uh-oh!’). In the Dhivehi Romanization system this glottal stop—whether it should be spelled with alifu sukun or shaviyani sukun—is supposed to be written as ‘h’. Western scholars, as Gnanadesikan has described, have criticized the official Dhivehi Romanization system precisely because of this ambiguity: ‘h’ in the syllable-final position can represent either alifu sukun or shaviyani sukun.Footnote 65 Yet these scholars seem to have been unaware of a test Maldivians learn at a young age to identify whether the letter for the glottal stop should be alifu sukun or shaviyani sukun. Regarding this matter, Naibu Thuhthu wrote,

One knows to spell the glottal stop at the end of a word with a sukun on shaviyani rather than with alifu sukun by [a validation test that involves] changing the pronunciation from a glottal stop to a shaviyani aba-fili. If that word's meaning remains intact then the glottal stop should be spelled with shaviyani sukun rather than alifu sukun.Footnote 66

Naibu Thuhthu alluded to the fact that in the Maldives children are taught a method to identify whether the glottal stop at the end of Dhivehi words should be spelled with shaviyani sukun or alifu sukun. The test is to change the pronunciation from a glottal stop to a shaviyani aba-fili and see if the meaning is affected. If the meaning stays intact, then shaviyani sukun is correct. For example, consider the word ‘geah’ (to the house). Ge means ‘house’ and -ah is the dative case and means ‘to’. At the end of the word ‘geah’ one hears the glottal stop. If one spells the final glottal stop with shaviyani abafili, then the word becomes gea+sha. Geasha like geah means ‘to the house’. The reason that the meaning of ‘geasha’ is the same as ‘geah’ is because in some dialects of Dhivehi the shaviyani sukun appears as shaviyani + aba-fili for the dative case. Thus this exercise reveals that the glottal stop should be spelled with a shaviyani sukun and not with an alifu sukun.Footnote 67

As mentioned above, another reason the sukun is a complicated phenomenon is because when four letters follow the sukun it triggers nasalization. More specifically, if the letters alifu, haa, noonu, and meemu come after a letter that carries a sukun these letters add a nasalization to the glottal stop. To remember the four letters that trigger a nasalized sound Maldivians today learn the acronym ‘a-haa-na-ma’.Footnote 68 Here the four initial letters of each syllable of a-haa-na-ma represent the four Thaana letters of alifu, haa, noonu, and meemu.Footnote 69 In 1890, Naibu Thuhthu referred to the rule with three different mnemonic devices: ‘hoa-ma-i-n’ (lit. from Monday), ‘he-u-na-ma’ (lit. if good), and ‘u-haa-na-ma’ (lit. if happy).Footnote 70

Naibu Thuhthu again articulated a language ideology but this time regarding the correct pronunciation of the nasalization. His idea was similar to his earlier suggestion that the improper pronunciation of aibai-fili was unpleasant: Naibu Thuhthu regarded the correct pronunciation of nasalization as pleasant or appealing (Dh. rivethi): ‘If alifu sukun or shaviyani sukun are followed by the letters found in [acronyms like] “hoamain”, “heunama”, or “uhaanama” it is pleasant for the speaker to pronounce the alifu sukun or shaviyani sukun as though with a noonu sukun [nasalization].’Footnote 71

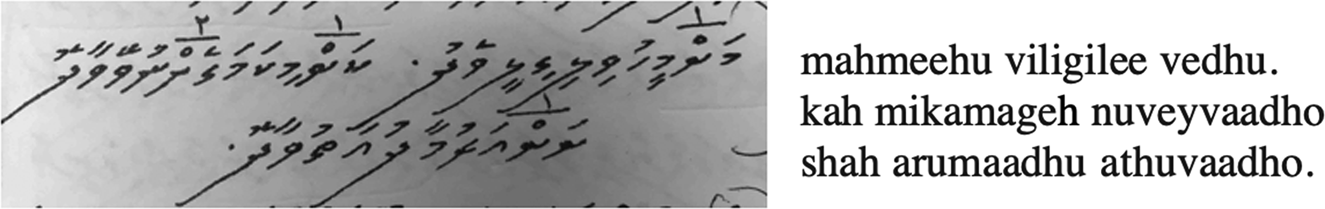

For evidence of this pleasant phenomenon, Naibu Thuhthu again turned to the realm of verse. He presented another raivaru verse composed by Ban'deyri Hasan Manikufaanu. This time he cited the thirty-fourth verse from Manikufaanu's long poem Dhivehi Arumaadhu Raivaru (Raivaru for the Maldivian Fleet of Ships). Naibu Thuhthu wrote, ‘In the words of the following three lines of poetry one thinks that the alifu sukun and shaviyani sukun sound like a noonu sukun.’Footnote 72 Figure 5 below presents an image of the poem as it appeared in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id alongside a transliteration.

Figure 5. Citation of verse 34 of Dhivehi Arumaadhu Raivaru, in Jamālluddīn, Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id, p. 9.

Consider how Naibu Thuhthu annotated this verse. He used the Arabic numeral symbols ![]() (1) and

(1) and ![]() (2) to mark the instances where nasalization should be produced. He placed the first two instances of the symbol

(2) to mark the instances where nasalization should be produced. He placed the first two instances of the symbol ![]() on top of the shaviyani sukun, which in the recitation of the verse should have been pronounced with nasalization because it is succeeded with a meemu. He placed the third instance of

on top of the shaviyani sukun, which in the recitation of the verse should have been pronounced with nasalization because it is succeeded with a meemu. He placed the third instance of ![]() on a shaviyani sukun that should have been pronounced with nasalization because it is succeeded with an alifu. Naibu Thuhthu placed the symbol

on a shaviyani sukun that should have been pronounced with nasalization because it is succeeded with an alifu. Naibu Thuhthu placed the symbol ![]() on an alifu sukun that should have been articulated with nasalization because it is followed with a noonu.Footnote 73

on an alifu sukun that should have been articulated with nasalization because it is followed with a noonu.Footnote 73

Again, to describe the linguistic phenomenon Naibu Thuhthu drew on an analogous concept in Arabic linguistic theory. He wrote, ‘When one puts sukun on alifu or noonu and pronounces the letter it seems that the pronunciation involves ghunna.’Footnote 74 The Arabic term ghunna (غُنَّ ) refers to nasalization pertaining to Quranic recitation.Footnote 75 When the Arabic letters mīm or nūn carry the shadda diacritic, the reciter creates a nasalization sound for a length longer than a short vowel mark.

The purpose of this section was to analyse Naibu Thuhthu's ‘poetry for linguistic description’ as found in his study Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id. It was revealed that in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id Naibu Thuhthu described facets of the Dhivehi language through the lens of Arabic linguistic theory, and he presented examples of Dhivehi verse as evidence for his linguistic prescriptions. Specifically, in discussions of the vowel aibai-fili Naibu Thuhthu represented the vowel sound with Arabic letters, like scholars today use the IPA symbols. Further, he found concepts, like tashdīd and ghunna, from Arabic linguistic theory useful to understand how the sukun is used for geminate consonants and how it produces nasalization. To illustrate what he believed to be the correct spelling and pronunciation of words with aibai-fili vowels as well as the proper nasalization that results from letters carrying the sukun, Naibu Thuhthu examined verses of raivaru composed by Hasan Ban'deyri Manikufaanu. In the next section, I examine the second sense of this article's title—‘Poetry for Linguistic Description’—through an exploration of how Naibu Thuhthu crafted verses about concepts in Arabic linguistic theory.

Poetry for linguistic description 2

Naibu Thuhthu's ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’

While exiled in Fehendhoo in 1890 Naibu Thuhthu also completed a work of poetry comprising 34 stanzas.Footnote 76 He crafted his verses according to the stylistic conventions of the Maldivian genre of poetry known as raivaru.Footnote 77 He bestowed on the work the Arabic-language title, ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’ (Correct Language). The purpose of the poem was to suggest that understanding core concepts in Arabic linguistic theory facilitated the craft and comprehension of Dhivehi poetry.

Naibu Thuhthu prefaced his poem with an epigraph which was a citation from a sixteenth-century Arabic text. The text's author Sharaf ad-Din Yahya ibn Nūr al-Din (d. 1581) had written the text as part of an introduction to a widely circulated thirteenth-century grammar of the Arabic language, al-Ājurrūmīyya.

Nūr al-Dīn's idea, which Naibu Thuhthu cited for his epigraph, can be translated in this way: ‘It is best to learn grammar first because without it speech will not be understood.’Footnote 78 As grammar imbued speech with meaning, ad-Din suggested, it was necessary to study grammar (naḥū) to truly understand speech (kalām). It is fitting that Nūr al-Dīn wrote this passage about speech for his introduction to the al-Ājurrūmīyya because its opening chapter offered a definition of speech from a grammatical point of view. I discuss this definition in more detail below.

In verse 1, Naibu Thuhthu evoked the idea of the epigraph. Consider verse 1 in translation:

In line 1, Naibu Thuhthu used the imperatives ‘ponder’ and ‘understand’ to request the reader to focus on the forthcoming message. In line 2, he promised he would flawlessly convey the message. In lines 4–6, he echoed Nūr al-Dīn's emphasis on the importance of grammar. Specifically, Naibu Thuhthu suggested that it was impossible to utter a word that lacked the inflection of grammar.

While the meanings of lines 1, 2, and 4–6 are fairly closed for interpretation, the connotation in line 3 of the adjective ‘pathetic’ and this adjective's referent are open for interpretation. I translated line three as ‘However pathetic’. The Dhivehi adjective here is dhera which denotes ‘sad’, ‘pathetic’, and ‘inferior’.Footnote 80 It is possible that Naibu Thuhthu used the word dhera to connote ‘uneducated’. If so, he may have been referring generally to all individuals everywhere or even to the specific reader of the poem. Accordingly, the connotation here could have been, ‘however uneducated one is’, ‘however uneducated people are’, or ‘however uneducated you, the reader, are’.

There is, however, another way to interpret the referent of the adjective dhera. It is not improbable that Naibu Thuhthu used the word dhera as an adjective to sarcastically allude to how, from his perspective, Maldivians (or maybe his circle of Maldivian friends?) sometimes considered the Dhivehi language as ‘inferior’ or ‘underdeveloped’ in comparison to other languages. I suggest the possibility of this interpretation because of the way Naibu Thuhthu used the term dhera in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id, which he authored in the same year as ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’:

For any group, the language they speak and the letters they use to write are excellent for that group. However pathetic [dhera] the language is, the language spoken by the people is the most excellent language. It is said that the Dhivehi language is inferior [dhera] to Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, Tamil and many other languages.Footnote 81

In light of this usage it would not be amiss to conjecture that one goal of Naibu Thuhthu's projects involving poetry for linguistic description was to ‘raise the standards’ of Dhivehi-language knowledge production.

As stated, one of the chief purposes of the poem ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’ was to introduce grammatical concepts of Arabic linguistic theory and stress that poets must comprehend these concepts in order to write good poetry. Yet Naibu Thuhthu did not mention the topic of poetry in verse 1. Why would he begin a poem about grammar-and-poetry with a stanza about speech?

The logic of this action suggests that Naibu Thuhthu conceived of Dhivehi poetry, at least the genre in which he wrote—raivaru—to be quintessentially oral and aural (like speech), rather than written and visualized on a page. In fact, it is beyond question that raivaru was originally meant to be recited. For example, in Thaana Liumuge Qawā‘id when Naibu Thuhthu introduced the topic of the Thaana letters that could carry the sukun he wrote, ‘Currently it has become very rare for people to understand the letters onto which the sukun is added for writing, speaking, and the recitation of poetry.’Footnote 82 Note how Naibu Thuhthu did not write the ‘writing of poetry’ (lhenbas liumugai) but rather the ‘recitation of poetry’ (lhenbas kiyai ulhunumugai).Footnote 83

In verse 2 of ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’ Naibu Thuhthu suggested that one needed to learn the rules of speech to comprehend and compose raivaru.Footnote 84

In this verse, Naibu Thuhthu constructed a metaphor of ‘untangling knots’ to portray the challenging process of decoding Dhivehi poetic language in raivaru.Footnote 86 It is possible that he meant this metaphor to refer specifically to the sometimes tough process of unscrambling syllables in raivaru. Lines of raivaru that involve multiple steps of unscrambling can be quite difficult to unravel, like the untangling of a difficult knot.Footnote 87 A literal translation of this unscrambled phrase would be something like ‘to untie without a knot being there’ (nanuge gosheh nethi mehadhinun).Footnote 88

In verse 2, Naibu Thuhthu introduced what would become a recurring rhetorical strategy: he created an anonymous character whose attitudes he sought to correct. For example, in verse 2 the character is someone who ‘has not studied much’ (line 1) and does not ‘know the rules of speech’ (line 3) yet mistakenly believes that he has comprehended poetry (line 2).Footnote 89 Naibu Thuhthu took a similar approach in verse 3:

Here, too, an uneducated character falsely assumes his words are beautiful but lacks the requisite knowledge to understand poetry.

Naibu Thuhthu may have derived inspiration for verse 3 from the opening idea expressed in Chapter 1 of al-Ājrūmīyya, the aforementioned thirteenth-century grammar of the Arabic language. Recall that the epigraph Naibu Thuhthu chose for ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’ was written by Sharaf al-Din Yahya ibn Noor al-Din in the 1500s in his introduction to al-Ājrūmīyya. Thus, one can assume Naibu Thuhthu was familiar with al-Ājrūmīyya.

One can further suggest that Naibu Thuhthu derived inspiration for verse 3 from this idea because Chapter 1 in al-Ājurrūmīyya defined ‘speech’ (al-kalām) as utterance that combines or connects (murakkabu, ‘compounded’) words and is ‘meaningful’ (al-mufīdu, literally ‘that which is beneficial’).Footnote 91 It is precisely this definition of speech that Naibu Thuhthu creatively employed in verse 3 to speak about the comprehension of poetry. He argued that ‘one surely cannot understand the meaning of poetry’ (Dh. maana hilaa nunereveyshi) without deeply considering ‘how speech is compounded’ (Dh. kalima murakkabu vaa goiy).

In verse 4, Naibu Thuhthu continued to focus his readers’ minds on the anonymous character with attitudes in need of correction. Here, the character was someone who authored incomprehensible song texts for a popular Maldivian musical genre:

Notice the italicized term baburu bas. The Dhivehi word baburu means ‘African’. In this context, the term baburu bas literally meant ‘African language’, but Naibu Thuhthu was probably referring to baburu lava (lit. African song).Footnote 93 Baburu lava is a Maldivian genre of song accompanied by the bodu beru, a double-headed barrel drum. It is said to have originated in Feridhoo in Ari Atoll. Historian Naseema Mohamed explains that,

A group of slaves brought to Maldives by a sultan are said to be the ancestors of many of the people on this island [of Feridhoo]. These freed slaves integrated into the community easily. Such slaves brought the sound of the African drum into the cultural music of Maldives.Footnote 94

According to historian Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya, Maldivians trace baburu lava back to a slave named Sangoaru, who lived on the island of Feridhoo who was brought to the Maldives by a Maldivian sultan who went to Mecca on pilgrimage. Jayasuriya suggests that African slaves in the Maldives were usually brought from Zanzibar, Muscat, or Jeddah.Footnote 95

Jayasuriya further noted that, ‘the words in the original [baburu lava] songs were not comprehensible to Maldivians’.Footnote 96 Given the fact that the original baburu lava songs were in a language foreign to Maldivians, one can understand Naibu Thuhthu's advice in verse 3: ‘In poetry recited by Maldivians, please do not assemble words in which no one will be quite able to comprehend what is being said, in such a way that one must endlessly swirl it in the mind, in a way that is done in baburu bas.’ That is, Naibu Thuhthu believed that poetic language must be fashioned in such a way that it did not require too much work to interpret the language's meaning as required by incomprehensible baburu lava.Footnote 97 Naibu Thuhthu symbolized the mental exertion to decode poetry as an act that required one to continuously swirl thought in the mind (hithu therey abura aburaa), and he represented the labour intensive process of decoding as an act of cleaning out dirt (kilaa nagai madhu nuvaa hen).Footnote 98

In verses 5, 6, 8, and 11 Naibu Thuhthu went from the general to the specific. He shifted from his earlier general assertation that grammar was necessary in order to comprehend poetry towards the identification of fundamental concepts in Arabic linguistic theory, concepts that Naibu Thuhthu believed his anonymous character needed to know. Below I present verses 5, 6, 8, and 11 in prose form.

I am saying with a pure heart that I believe no one can comprehend the true meaning of a recited poem without identifying the subject [fā‘il] and verb [fi‘ul] (v.5).Footnote 99

Believe me, if you have not learned the subject [fā‘il] and object [maf‘ūl] regardless of how long you keep trying you will not be able to comprehend the true meaning of a well-delivered poem without tainting it (v.6)Footnote 100

When you walk onto an unknown path of [concepts like] present tense [māḍee], past tense [muḍāri], first person [mutakallim], second person [mukhātab], definite [ma‘rifa], and indefinite [nakira] if you have the attitude ‘I am content with what I know’ you will never understand the meaning of the poem (v. 8)Footnote 101

One can understand the meaning of poetry only after pondering the nisba suffix to form adjectives [nisba], that which is possessed in an iḍāfah construction [muḍāf], the circumstantial qualifier [h‘āl], the adverb of time [ẓarf zamāna], the caller [munādī], the person called [munādā], and the adverb of place [ẓarf makān]. (v. 11)

Thus readers of these four verses would have thus encountered the following 16 concepts that remain fundamental to Arabic linguistic theory:

1. fā‘il = subject

2. fi‘ul = verb

3. maf‘ūl = object

4. māḍī = past tense

5. muḍāri = present tense

6. mutakallim = first person

7. mukhātab = second person

8. ma‘rifa = definite

9. nakira = indefinite

10. nisba = suffix to form adjectives

11. muḍāf = that which is possessed in an iḍāfah construction

12. h‘āl = the circumstantial qualifier

13. ẓarf zamāna = the adverb of time

14. munādī = the caller

15. munādā = the person called

16. ẓarf makān = adverb of place

Note, however, how Naibu Thuhthu did not define these terms. Rather, he states that everyone needs to understand such grammatical categories to comprehend poetry. Given the epigraph and the content of these verses, one could again persuasively speculate that when he presented these terms he had in mind chapters from al-Ājurrūmīyya. Chapter 15 of al-Ājurrūmīyya named 15 parts of speech, which include maf‘ūl (object), ẓarf zamāna (the adverb of time), ẓarf makān (the adverb of place), and h’āl (the circumstantial qualifier). Chapter 18 of al-Ājurrūmīyya focused exclusively on the ẓarf zamāna and ẓarf makān while Chapter 19 dealt with the circumstantial qualifier.

The purpose of this section was to examine how Naibu Thuhthu made Arabic linguistic theory the main topic of his poem ‘Taqwīm al-Lisān’. It was revealed that Naibu Thuhthu seems to have been inspired by al-Ājurrūmīyya and strived to teach his readers that raivaru poetry like speech necessitated the understanding of key grammatical concepts.

Conclusion

When one considers the Arabic cosmopolis in the Maldives via Naibu Thuhthu's writings in 1890, one could characterize the relationship of the Maldives to the Arabic cosmopolis as connected in some ways but disconnected in others. The Maldives was connected with the superculture of the Arabic cosmopolis in the sense that Naibu Thuhthu explained aspects of the Dhivehi language with the assistance of the Arabic script and Arabic linguistic theory. He symbolized the phoneme of the aibai-fili vowel with Arabic script, as one would use the IPA today. He utilized concepts in Arabic linguistic theory like tashdīd and ghunna to explain how the sukun behaved with geminate consonants and produced nasalization. He even crafted verses of raivaru about core concepts in Arabic linguistic theory, concepts that he may have learned from the Arabic grammar al-Ājurrūmīyya.

Yet Naibu Thuhthu's poetry for linguistic description was simultaneously disconnected from the Arabic cosmopolis on account of the fact that there is no evidence that non-Maldivians living outside of the Maldives in the Arabic cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia could read the Thaana script of the Dhivehi language. Thus, the case of Naibu Thuhthu's two Dhivehi texts encourages acknowledgment of forms of intercultural disconnection within a cosmopolis.

This case study affords us the opportunity to reflect upon the efflorescence of ‘cosmopolitan vernaculars’. Pollock coined the term to describe how writers throughout South and Southeast Asia in the second millennium began to use vernacular languages for epigraphy and then literary expression, rather than the cosmopolitan language of Sanskrit. Yet when these writers used the vernacular they infused the vernacular texts with cosmopolitan norms from Sanskrit epigraphy and literature.Footnote 102 Pollock's analysis of this phenomenon prompted him to write, ‘It was predominantly Sanskrit knowledge and texts that underwrote the literization of the vernaculars and many of their most dramatic inaugural…productions.’Footnote 103 In The Language of the Gods in the World of Men Pollock analysed the process of cosmopolitan vernacularization through the lens of the history of written texts in the Kannada language. He also surveyed the literary histories of Marathi, Javanese, Sinhala, Tamil, Telugu, and briefly touched upon the literary histories of northern languages like Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Newari, and Oriya.Footnote 104

In Islam Translated, Ronit Ricci turned the discussion towards three vernaculars in South and Southeast Asia—Javanese, Tamil, and Malay—that came under the influence not of Sanskrit but of Arabic. The era of cosmopolitan vernacularism in the Arabic cosmopolis began approximately 500 or 600 years later than that of the Sanskrit cosmopolis, which Pollock suggested commenced with the turn of the second millennium. Ricci discussed how ‘Arabic…was vernacularized’ in Javanese, Tamil, and Malay translations of the Arabic Book of One Thousand Questions, translations that can be traced to the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 105 Ricci also explained that cosmopolitan vernacularism in the Arabic cosmopolis diverged from the Sanskrit and Persian cosmopolises: in the Sanskrit and Persian cosmopolises writers drew upon secular ideas, values, and aesthetic sensibilities. In contrast, in the Arabic cosmopolis a major impact on cultural production was the Islamic religion.Footnote 106

Due to the fact that Naibu Thuhthu infused cosmopolitan Arabic linguistic theory into his vernacular linguistic description and poetry, it seems appropriate to consider Naibu Thuhthu's texts as a Maldivian instance of cosmopolitan vernacularism in the Arabic cosmopolis. Yet it should be stated at the outset that Naibu Thuhthu wrote the aforementioned texts while he was in exile. In contrast, literature in the Sanskrit, Persian, and Arabic cosmopolis tended to be created under the patronage of royal courts.Footnote 107

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the support of the many members of the Facebook group Bas Jagaha, a forum dedicated to the study of the Dhivehi language. Thank you to Ahmed Omar and Mohamed Haneef for generously answering hundreds of questions. I wish to thank Ibrahim Sameer for unscrambling and explaining the meaning of Naibu Thuhthu's raivaru and Naajih Didi for your assistance. Thank you also to the following individuals for helping me to complete this article: Ashraf Ali, Mohamed Abdulla, Thirugey Beyyaa, Abdul Latif ibn Ahmad Hasan, Ibrahim Shareef Ibrahim, Muneer Manikfaan, Siraj Mohamed, Hasan Fazloon Bin Muhammad, Mohamed Musthaq, Iyaz J Naseem, Unmu Akoo Nick, Fath Na C Ra, Abdul Ghafoor Abdul Raheem, Safiyyuddeen Rasheed, Raaif Rushdhee, Shayadh Saeed, Sariira A. Shareef, Ahmed Sharyf, Ahmed Shihan, Yanish Suveyb, and Hassan Waheed. Finally, I wish to thank the anonymous reviewers of MAS for invaluable feedback which significantly improved the quality of this article.

Competing interests

None.