A Roman castellum at Chott Chergui

Introduction

The subject of this archaeological note is the Roman castellum at the site of Saf-Saf Lakhdar. This note is divided into two parts, the first of which is devoted to the description of the castellum in its geographical and architectural dimensions. This fortification was separate from the Roman limes Footnote 1. It is completely covered by the soil and sand of the Sahara. The second part describes the inscription discovered in the place called ‘Khnag ‘Azzir’, 30 km from Saf-Saf Lakhdar. This inscription provides conclusive epigraphic evidence of the Roman presence in the southern area of the ChottFootnote 2 Chergui and in the northern part of the Saharan Atlas, as well as evidence of the situation and the historical context. It also reveals the conflictual relations between the Romans and the local tribes (Bavares).

Without claiming to evaluate them, the works carried out on Algerian territory concerning the Roman presence have concentrated mainly on the provinces of Mauretania Sitifensis, Numidia Cirtea and Numidia Militare. As for Caesarian Mauretania, archaeological studies have concentrated mainly on its northern part, on the border between the Oranian plateau and the coast (Yahiaoui Reference Yahiaoui2003).

The site of Saf-Saf Lakhdar was discovered by chance during a truffle hunt in the Chott Chergui, at the foot of the Ksour mountains, in the western part of the Saharan Atlas (Algeria). My interest was then directed towards a Roman fortification. But the literature review and historiography of the region do not point to any evidence of Roman presence, although P. Salama's map of the road network mentions the possibility of tracks crossing beyond the Roman frontier road, on the southern borders of the province of Caesarian Mauretania (Salama Reference Salama1951).

The hypothesis is that the remains discovered are those of a castellum, based on its location, which suggests a Roman military defence construction (Bardouille Reference Bardouille2010). This is supported by the discovery of an inscription by Drici, not far from Saf-Saf Lahkdar and 5 km north of the town of El Bayadh, at a place called ‘Knag Azzir’, which opens up new historical perspectives on the Roman presence and its relations with the indigenous tribes. Indeed, this inscription reveals Roman penetration into the confines of the desert, far from the Severan limes (Drici Reference Drici2015). If the hypothesis is confirmed, this fort would have belonged to a first defensive system that surrounded Caesarian Mauretania. The Romans were thus able to keep an eye on the western part of the Chott Chergui, which separates the Saharan Atlas and the Sahara from ‘useful’ Africa. They would have built it to protect themselves from looters and nomadic tribes coming from the Saharan Atlas and the desert. The architectural aspects of the remains, at first sight, could be classified as Roman defensive architecture (Ginouvès et al. Reference Ginouvès and Martin1985).

State of the castellum

Roman military architecture in North Africa is unique. There, the Romans did not follow the patterns of construction designated from Rome (Toutain Reference Toutain1903). They did not build their camps and garrisons according to the single model that prevailed in the Roman Empire, both in the West and in the East (Trousset Reference Trousset1974). Lenoir has proposed a general re-reading of the full complexity of the empire's military systems and strategies in areas on the edge of the desert, in contact with nomadic populations, highlighting their originality in Roman tradition and as an expression of imperial power (Lenoir Reference Lenoir2011). By means of a typological study, the author distinguishes six main classes of constructions and suggests a period of use for each of them. The development of the fortifications, particularly the towers protecting the gates, is less linear than is generally assumed. The principia (the administrative quarter at the centre of the camp) became increasingly important and its religious function, linked to the cult of the ensigns and the emperor, became predominant.

The castellum of Saf-Saf Lakhdar is located in the Chott Chergui in the western part of the Saharan Atlas (Algeria), and its name has both a botanical and a chromatic meaning. Saf-Saf refers to the willow, the only tree species present on the site, and Lakhdar means ‘green’, in reference to the green landscape of the place, in contrast to the ochre and yellow semi-desert of the surrounding environment.

This outpost, the southernmost of the fortifications of Caesarian Mauretania, is located 350 km southwest of Oran, in the Algerian pre-desert, on one of the last southern ranges of the Saharan Atlas. It is strategically located on a natural axis of north–south communication, in an intermediate zone between the northern plains and the Ksour mountains (Saharan Atlas).

The site is marked by a hill that surrounds it to the north, west and south. This hill is called Rjal el Gara, which literally means ‘the men of the cave’. On this hill are four mausoleums surmounted by ogival domes (local style) (Djeradi Reference Camps2021), built in honour of the saints of the region. The ground is rocky and salty. It is covered by steppe vegetation dominated by alfa and halophytes. The substratum consists of limestone and a high density of layers of clay silt (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The physical, natural and human environment of Saf-Saf Lakhdar (Djeradi, July Reference Camps2021).

1 Agricultural plot fenced with stones of fortification

2 Remains of a circular tower

3 Water source of Sfissifa

4 Foundations of square tower

5 Willow tree

ABC Remains of facades of soldiers’ supposed homes

D Illustration of foundations of square tower

E Remains of surrounding wall

F Remains of front door

G Illustration of circular tower remains

H ground plan of castellum (top left: western watchtower; bottom right: southeast watchtower; centre bottom: entrance door; bottom left: southwestern watchtower)

The water source of the Saf-Saf is still flowing. The nomads have built a basin and a well. Close to this water source, we discovered the remains of a circular tower (3.60 m in diameter). On the southwestern side of the wall, the foundations of another square tower (4.00 m x 4.00 m) are clearly visible. On the other side of the wall, at the edge of the flow of the Saf-Saf, there are clearly visible mounds of stones of uniform shape and size, similar to barrows. We can hypothesise that this is indeed a cemetery where the soldiers of the garrison were buried. Further south, there are nomadic dwellings built with the stones of the castellum.

The fort is rectangular in shape, built on a plateau that slopes slightly to the north. The rampart measures 110 m by 150 m and 1.35 m thick. It has a single gate and three towers. There are some traces of the interior of the fort. It was probably divided into dwellings, shops and stables, corresponding to a military post that would have been occupied by limitanei rather than comitatenses (elite troops) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ground plan of the Saf-Saf Lakhdar's castellum (Djeradi, July Reference Camps2021.

A Saf-Saf Lakhdar vegetation cover

B Willow tree, toponymic reference

C Limestone rock around remains (in rectangular box)

D Chott Chergui settlement

E Clay-loam layers (line above); limestone layers (line below)

Other elements that we think we can identify are vaulted rooms, of which only a few sections remain. Some traces have been preserved of two towers, the foundations of which have a rectangular bipartite plan 4 m x 3.5 m), located on the southwest and southeast façades. The walls are 1.60 m thick. The gate tower protrudes from the centre of the south wall. It is not on the line of the enclosure. Only the south side of the gate is partially preserved with an opening of 2.80 m on the east side. It is a staggered entrance with a depth of 3 m (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Development plan and environment of the supposed Saf-Saf Lakhdar's castellum (Djeradi, July Reference Camps2021).

The inscription of ‘Khnag ‘Azzir’, a major revelation

• Support: a limestone plaque.

• Description: An inscription in which the last five lines are entirely hammered out. It is laid out in eight lines of 8-cm-high letters (Figure 4).

• Text:

-

IOVI OPTIM MAX

-

ET DIS FAUTORIB

-

VOTUM

-

C OCTAVIUS PUDENS

-

PROC SEVERI

-

AUG

-

BAVARIB CAESIS

-

CAPTIS QUE

-

-

Translation: To the god Jupiter most good and great and to the patron deities. This is an offering from Caius Octavius Pudens who is procurator of Augustus. In honour of the elimination and capture of the Bavares.

This inscription contains three extremely important revelations.

1. It is dedicated to the god Jupiter to commemorate a victory over the Bavarians.

2. The inscription reveals the existence of a person called Caius Octavius Pudens.

3. It sheds light on certain aspects of the main conflicts linked to the Roman invasion of the Saharan Atlas.

Figure 4. The inscription of ‘Khnag ‘Azzir’ (Djeradi, January Reference Camps2021).

This inscription shows the Roman penetration of the desert confines far from the Severan limes, while at the same time revealing previously unpublished historical facts. According to Drici, this inscription contains three revelations (Drici Reference Drici2015).

The revelation about the deities

The inscription is dedicated to deities to commemorate a victory over Berber tribes from the Saharan Atlas (Baquates, Bavares, Fraxens or Quinquegentanii). It was traditional to honour the god Jupiter for the success and supremacy of the Romans over their enemies. Although the god Jupiter is attested on countless occasions, the ‘Dis Fautores’ are an exception. Drici raises the question of whether the inscription ‘Dis Fautores’ refers to partisan or protective deities. Didn't they, in this sense, lend a helping hand to the procurator Caius Octavius Pudens to defeat the Bavarians? This inscription is not very common in the lists and indices of North-African inscriptions.

The revelation about Caius Octavius Pudens

The procurator Caius Octavius Pudens is a well-known figure from various sources (Pallu de Lessert Reference Pallu De Lessert1969; Thomasson Reference Thomasson1984; Christol Reference Christol1992). It has been established that he served during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus – who, it is assumed, reigned between the years 198 and 211, based on his association with his correlatives, his sons Caracalla and Géta (Dupuis et al. Reference Dupuis and Kasdi2021). Pallu de Lessert had established the entire reign of Septimius Severus to have lasted from 193 to 211, but a re-reading of the inscriptions and a comparison of historical events with the work of this procurator led M. Christol to settle on a revised start date of 198. On this point, he agrees with and supports the views of Salama (Reference Salama1951). Using the work of Benseddik (Reference Benseddik1991), Magioncalda (Reference Magioncalda2006) places this procurator at 198–200. All these references have the merit of helping to date this inscription and, consequently, that of the Saf-Saf Lakhdar castellum.

According to Christol (Reference Christol1992), Caius Octavius Pudens was not known as a military leader, but was valued above all for his work on roads and public buildings. He probably confronted the Bavarians when he entered their territory to build a road linking the Dimmidi military camp to the Saf-Saf Lakhdar camp, thus forming a frontier in front of the Chott Chergui. This road provided a link with the Roman road further north, the Severan limes (Salama Reference Salama1951).

The revelation about the Bavarians and the Romans

The inscription highlights the conflicts between Rome and the Bavarians and the designation of this tribe as a major player in the troubles of the ancient Maghreb. The epigraphic record reveals the presence of the Bavarians from the third to the fifth centuries as a major factor in the resistance against the Roman forces (Desanges Reference Desanges1962). And the fact that they were found in several places at once suggests that the Bavarians were a nomadic people, or that they were divided into several branches with the same ethnonym.

Camps (Reference Camps1991) affirmed that the Bavarians were part of the Moorish confederation. He divided them into two distinct entities: the Eastern Bavarians, whose area of occupation extended into Setifian Mauretania, and the Western Bavarians, whose territorial limits were located in the western part of Caesarian Mauretania, more precisely in the Traras, Dahra and Ouarsenis mountains. The inscription, because of its geographical location and the message it conveys, has led us to reconsider the territoriality of the Bavarians: the message of the inscription mentions that there was a battle between the Roman troops commanded by Caius Octavius Pudens and the Bavarians in a place that has not yet been determined. This place was probably in the region where the inscription was found. It seems that in this semi-desert area, south of the Chott Chergui and at the northern foot of the Saharan Atlas, the Bavarians fought the Romans between 198 and 200. This probably prompted the Romans to build the castellum of Saf-Saf Lakhdar.

Conclusion

The limes was reinforced with the establishment of the advanced posts of Aïoun Sbiba and castellum Dimmidi (Benseddik Reference Benseddik1999). The castellum of Saf-Saf Lakhdar may have been erected to control the road linking Saf-Saf Lakhdar to the castella of Centuria (Aïn El Hadjar), Luccu (Timziouine), Ala MiliariaFootnote 3 (Béniane) and Cohors BreucorumFootnote 4 (Takhmaret). The main purpose of the roads in Caesarian Mauretania was to link the military posts responsible for defending the Roman provinces against the incursions of the nomads. During the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus, these military installations served as Roman stations and fortresses on a military route known as the ‘Nova Praetentura’, created to extend southwards the territories controlled by the Romans in Caesarian Mauretania.

The Saf-Saf Lakhdar outpost was probably designed to keep an eye on the nomadic tribes, controlling their transhumance corridors through the presence of fortifications, which made it impossible to cross areas that had been travelled for generations (Yahiaoui Reference Yahiaoui2003). The Roman authorities confined the Berber tribes to the foothills of the Saharan Atlas mountains. The restriction of nomadic areas must have led to tribal uprisings within these borders, although the evidence for this is extremely tenuous. Indeed, the El Bayadh inscription reveals one of the first clashes between Roman authority and a tribe developing in its traditional environment.

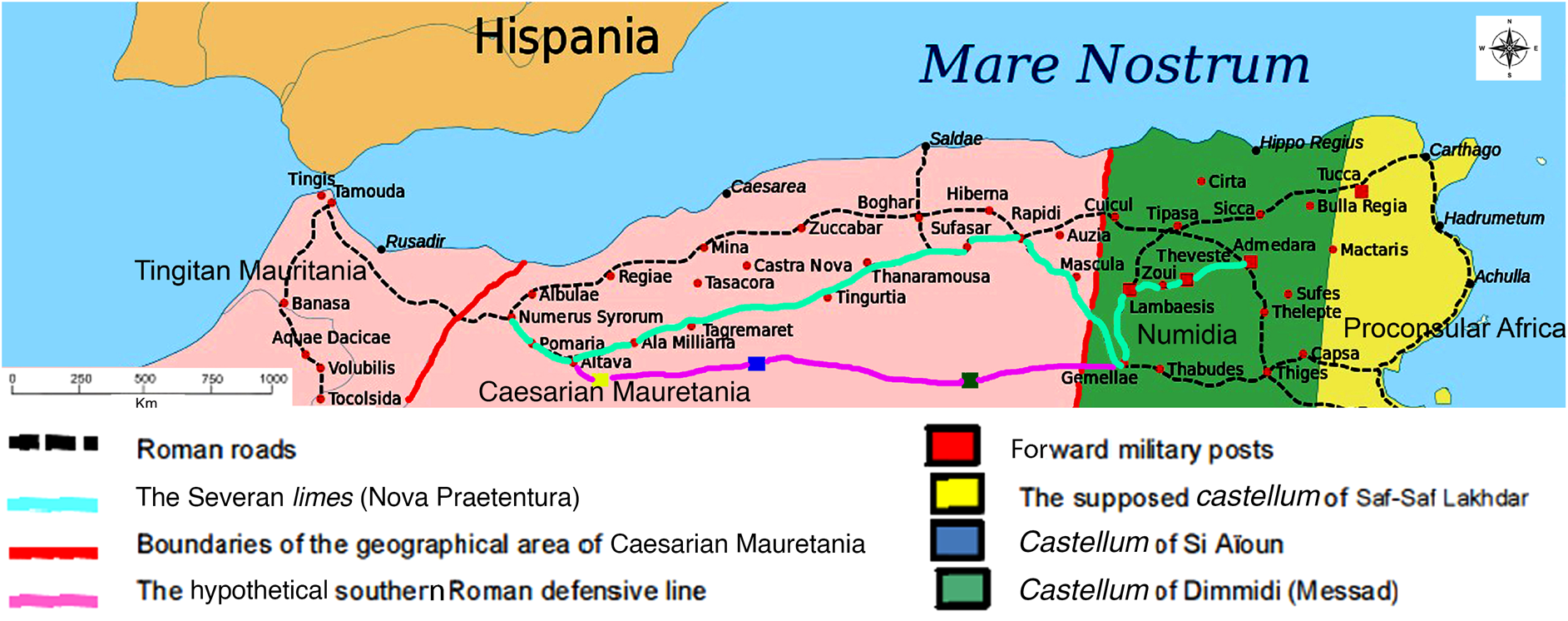

The Romans pursued a policy of expansion and conquest in which the wars were neither successive nor continuous (Le Bohec Reference Le Bohec1989). They occupied the interior of North Africa and adopted a defensive strategy that mobilised a new defence system for both civil and military needs. In order to monitor and protect a strategically or economically important civilian area, the Romans built military posts in Africa (Christol Reference Christol2015). These military buildings were laid out and divided into well-defined zones, designated by the term limes, which meant a long and narrow strip of land divided into several defensive systems. Under Hadrian or perhaps Trajan, the III Augusta Legion finally established its camp at Lambaesis;Footnote 5 Nerva built defences in Numidia Militare; and his successor Trajan ordered the occupation of the Aures mountains. Rome then controlled a strip of territory of 50 to 100 km from the coast to the mountain ranges of the hinterland. Hadrian consolidated the defensive system of Africa by creating units of Palmyrene archers (Baroni Reference Baroni2020). Under the Severans, the limes was developed in Mauretania. They built a new ‘Nova Praetentura’ ring road linking Rapidum (Djouab) in Numidia with AltavaFootnote 6 and to Numerus Syrorum (Maghnia), extending the control of Caesarian Mauretania to the south. Advanced posts in the desert controlled the nomadic tribes (Baratte Reference Baratte2012) – we can cite: castellum Dimmidi (Messâad oasis); Cydamus (Ghadamès); and Bu Njem (modern Libya) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Limes and fortified places in the second century (Eric Gaba. Available at: https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Africa_Roman_map.svg, modified by the author, March 2022, for clarity, see online colour version).

Many indigenous populations were able to live on the fringes of the Roman system, especially the nomadic tribes, who were driven back to the desert areas, to the point where the existence of two Africas was attested, one Romanised (useful Africa) and the other inhabited by the tribes of the mountains and deserts. It is in this context that we must look at the castella built between the Roman plains of the steppe and the desert territories inhabited by the refractory Berbers (Frémeaux et al. Reference Frémeaux and Le Bohec2007).

In conclusion, the location of the castellum of Saf-Saf Lakhdar was a matter of concern for Roman military defence strategies. This fort would have been part of a first-defence system surrounding Caesarian Mauretania. It allowed the Romans to monitor the western part of the Chott Chergui, which separated the Saharan Atlas and the Sahara from ‘useful’ Africa, and it would have been built to protect against raiders and nomadic tribes from the Saharan Atlas and the desert.

Despois, author of an excellent work on the Djebel Amour, claimed that there were no traces of Roman occupation beyond the Oran plateau (Despois Reference Djeradi1957). This paper refutes Despois's claims. In fact, after the discovery of the inscription of ‘Khnag ‘Azzir’, the Roman presence was confirmed well beyond the plateau, at the very northern limit of the Saharan Atlas.

The ruins of Saf-Saf Lakhdar are probably a Roman castellum; only archaeological excavations can scientifically prove this. It is now imperative to protect the site, to reconsider the entire archaeological map of Algeria and to review the limits of the Roman Empire beyond the established borders. This discovery is likely to shed new light on the perception of the intermediate territory between the high plains of the north and the mountains of the Saharan Atlas. It could also give rise to renewed interest in the Chott Chergui region as a whole.

Finally, we hope that this article, with the help of young people's heritage associations, will raise awareness among the local and central authorities of the need to protect the site and carry out excavations in the hope of finding pottery or other objects that might shed light on the existence of this fortification.