‘Attention must be paid to those whose endurance and struggle are so much of the ordinary stuff of everyday life that they are too easily taken for granted’ Footnote 1

Introduction

This paper explores the everyday lives of low-paid, low-skilled EU migrant workers living in and around Great Yarmouth, in the East of England, both pre- and post-Brexit, specifically in respect of their employment (law) issues. Most EU nationals who came to the UK did so for work. Significant empirical evidence shows that EU-10Footnote 2 migrant workers tend to be concentrated in low-skilled sectors for which they receive low pay. They are often hired through agencies or via gangmasters.Footnote 3 Using a mixed methods enquiry, including access to longitudinal quantitative data, and working with a grassroot community-based advice agency (GYROS), we consider the legal problems faced by EU migrants in the UK, especially around employment law, and how those problems are resolved, usually without any reference to any formal dispute resolution mechanism.

The aim of the paper is twofold. First, we examine the everyday (employment) problems faced by EU migrant workers and consider how GYROS seeks to help them. Secondly, we argue that the existing literature does not sufficiently capture this type of everyday street-level engagement with the law. We therefore advocate a new approach to understanding this type of engagement, that we term ‘pragmatic law’ (PL). We use the term PL to describe our experience that most legal issues, at least with the groups we are working with, do not enter any formal legal resolution pathway at a community level. They are addressed in the everyday, often by first-tier generalist (and sometimes volunteer) advisers with no formal legal training. This access to advice and problem resolution at a street level can be a lifeline to those living in areas of high deprivation where there is little free legal advice available, an issue exacerbated by intensive cuts to UK legal aid.Footnote 4

Our study of the everyday law experiences of EU migrants has taken place at a time of significant change in the UK immigration landscape, where over six million people (to date) have undergone a major immigration status change in the UK, moving (post-Brexit) from EU citizen exercising free movement rights, to EU Settled Status (SS) holder (for those with five years’ residence) or EU Pre-Settled Status (PS) holder (for those with less than five years’ residence) or, failing this, to that of being undocumented in the UK.Footnote 5

For many in the cohort that we are looking at, making this change of status has been difficult and for some it has exacerbated their existing vulnerabilities. It has meant increased ‘bureaucratic bordering’Footnote 6 (ie having to provide evidence of SS or PS to have access to, for example, housing, work, financial services, or secondary health services).

For the purposes of this paper, we define our cohort as ‘vulnerable’ and marginalised because they are individuals who have accessed community advice, often due to English-language barriers or immigration-related support needs. The majority of those in our research cohort work in what is termed ‘low-skilled’ employment, which often translates to low-paid employment, working in local farms, factories, warehouses and care homes. By vulnerability we mean people who live with ‘disadvantage and for one reason or another this disadvantage results in the accumulation of clusters of associated legal problems’.Footnote 7

So, what are those legal problems? What follows is an analysis of clients who have been accessing GYROS and its services over the last six years (although some as far back as 2012). GYROS is a charitable advice agency based in the East of England and it provides Office for Immigration Services Commissioner (OISC) accredited immigration advice and multilingual information, advice, advocacy and guidance (IAAG) to migrant communities. Its daily work is set out in more detail below. Our focus in this paper will be on the employment issues that clients have raised associated with being in low-paid work.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we begin by describing our methodology working with the longitudinal data set (section 2) and a descriptive analysis of the dataset (section 3). We then examine GYROS’ data and our findings with a particular reference to employment issues (section 4). Section 5 examines the approach taken by GYROS to resolving problems and how this relates to our concept of ‘pragmatic law’ (section 5). The paper ends with a brief conclusion.

1. Methodology and overview of the data

(a) Methods

For this research we have had access to a longitudinal dataset held by GYROS (Great Yarmouth Refugee Outreach and Support).Footnote 8 Within its advice service, GYROS offers an open access general IAG (Information, Advice and Guidance) service. Its advisers help with whatever issue comes through the door on the day of their drop-in, and they signpost clients to other services if they cannot help. All its frontline staff are multilingual and, as an organisation, it holds various accreditations including OISC (Office of Immigration Services Commissioner) Level 1 and Level 2 to give immigration advice, an FCA (Financial Conduct Authority) accreditation to give debt advice and the Matrix accreditation certifying its general advice service. The majority of its staff have lived experience of migration to the UK through various UK immigration routes. It offers advice services through a hybrid drop-in advice triage and follow up appointment sessions.

We obtained a download of GYROS’ database 2015–2020. The database records the enquiry labels that an individual seeks support under, including housing, employment, health etc (outlined below in Figure 2). A client's attendance at the service is recorded under the relevant enquiry label that their visit relates to on that day. Because clients can come in for help under the same enquiry label more than once – for example housing support over a number of years – the client is given an individual ID number allocated by the database. This unique ID number was used by the researchers to identify where the same client came in for help for more than one issue (other identifying information, such as name/address etc, was not shared within the dataset). All enquiries in the dataset are recorded under the relevant label (eg housing, employment) and a unique case note is recorded for each visit. Here, the dataset contains 1366 unique ID numbers and 3018 enquiry label entries (see Figure 2) which equates to 6856 unique case notes.

Analysis of the GYROS dataset involved two stages. First, a quantitative analysis of the descriptive data was undertaken using STATA, and the overview of these findings is provided in section 2 below. The second stage of the data analysis involved examining the free text of the client case notes attached to each enquiry label.

This qualitative data analysis required reading and analysing the client case notes attached to each enquiry label (6856 notes), developing themes and subthemes, and coding them, returning regularly to the original dataset to develop themes further.

The dataset was supplemented with material obtained from our attendance at weekly ‘complex case’ meetings from March 2020 to May 2021, at which GYROS frontline advisers meet to discuss their complex casework. Later in 2021, some of GYROS’ partner organisations also attended these online meetings to share practice and learning. The researchers have attended the meetings each week, recorded field notes and, where relevant, followed up individual cases. We have also undertaken three focus groups in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk (two multilingual focus groups with clients and one with GYROS staff), contextualising some of the findings from the database analysis. Further, we have undertaken an interview with a former recruitment agency worker to learn more about agency worker recruitment and employment practices in the area. The interview and focus groups were recorded and transcribed.

(b) Limitations of the data

In the first two stages of our methodology outlined above, we were analysing secondary data obtained from GYROS. This raises important questions about limitations related to the data which we have not captured through our own data collection methods. There are a number of different definitions of what secondary data analysis is,Footnote 9 in some instances even including re-analysing the researcher's own work. We use Glaser's definition, which is that our secondary data analysis involves ‘the study of specific problems through analysis of existing data which were originally collected for another purpose’.Footnote 10 We identify two limitations to this data. First, in examining the (legal) problems experienced by migrant communities in the East of England, the cases we have analysed concern, by definition, those who have sought help from GYROS. Cognisant of this limitation, in focus groups we asked specifically about where those who did not seek help from GYROS were likely to access help.

The second limitation we have noted is that the case notes analysed were written by GYROS advisers after they have seen a client or during their appointment with them. Each adviser has their own style of writing of case notes and they do so in English, which is their second or third language. Staff also vary in their experience as advisers, from new trainees to those who are Level 2 OISC immigration advisers whose service with GYROS ranges from less than a year to over 10 years. Case notes undergo case note supervision and auditing by the adviser's relevant line manager (for general advice) or by their subject lead for accredited advice (OISC or FCA). In addition, annual or bi-annual randomised audits of case work are undertaken by accrediting bodies such as OISC (for immigration advice). In this way, despite the number of individuals generating case notes, checks and balances are in place to maintain the standard of case notes recorded. But, as with Judith Mason's work on childcare proceedings where ‘court files rarely include accounts of the discussions between the parties during which agreements may be reached about directions, evidence or timetables etc’,Footnote 11 the case notes in our research are written by one party to the advice work, namely the adviser. However, in this research we are interested in the approach taken by GYROS (section 4) in helping people navigate (legal) problems and in this way the case notes provide a rich dataset in which to track the approach taken. The notes written by individual case workers provide valuable clues as to GYROS’ approach. In summary, while on the one hand a limitation, on the other, the notes themselves form an important part of our understanding of GYROS’ work.

3. Overview of the clients seen by GYROS

In this section we look at the numbers of clients seen by GYROS by age, gender and nationality, as well as the numbers and types of problems experienced by GYROS’ clients.

(a) Age, gender, nationality

The cohort in our dataset consists of 56.2% women, 41.2% men (and a further 2.7% where gender data is not specified). A broad range of ages is represented, spanning from age 20 to over 70. The mean age for women is 46, for men 45.5 years, with an overall mean of 45.7 years.

Figure 1 shows GYROS’ clients by country of origin. Nationals from Lithuania and Portugal represent 19% of the database. Additionally, those from Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Sao Tome and Principe and East Timor, all holding Portuguese nationality, are also represented. This brings Portuguese nationality holders to 37% of the total cohort – the largest group. Across the whole dataset, 85% are EU nationals and 3% non-EU family members of EU nationals (NEFMs), meaning that for GYROS, in the years 2015–2020, just over 10% of their clients were non-EU nationals. This country-of-origin data (with some 18% of EU citizens not from EU countries) highlights the spread of EU citizenship beyond the geographical borders of the EU.

Figure 1. country of origin

(b) The issues facing GYROS’ clients

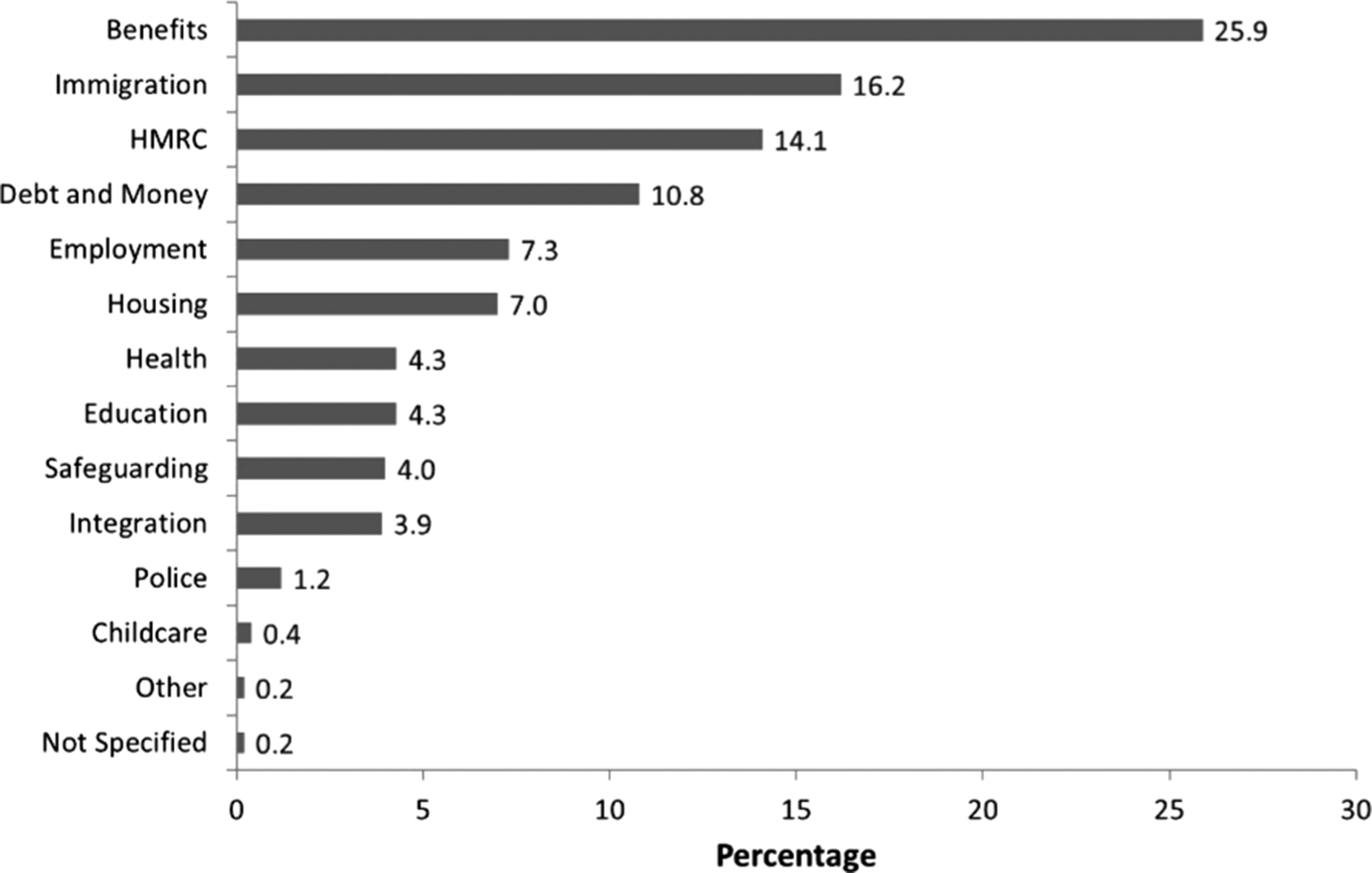

The data reveals (Figure 2) that the main issues that GYROS clients sought help for were: welfare benefits (26%), immigration (16%), HMRC (tax) related issues (14%), debt advice (11%) and employment (7%). However, other enquiries include health, education, and housing-related issues. Further, most issues are interrelated, with just under 50% of clients accessing GYROS for help with more than one issue at the same time, such as debt and housing or employment and welfare benefits. Some 26% of enquiries were for an individual accessing more than three services (help under three separate enquiry labels).

Figure 2. overview of database enquiries

UK immigration law underpins many of the issues faced by clients, particularly post-Brexit where some 6 million EU nationals now have to prove their right to rent, work and access NHS services (amongst many others) at many points using their newly-issued digital EUSS status. This is a key example of internal, bureaucratic bordering, adding to the bureaucratic burden experienced by migrant communities in both employment issues and other matters in terms of problem cluster creation, particularly where the inter-relationship between immigration status and employment is not recognised by the client.

The multiplicity of issues has an impact on the average timeframe over which a client interacted with GYROS. The average time across services was 16 months. This indicates that most clients are not ‘quick fix’, or single-issue clients; they come back numerous times, sometimes across multiple years, to access help. Accessing immigration support was the only service where the period of engagement was less (11 months). However, within this cohort, some immigration applications can take much longer, due to long waiting periods for Home Office decisions, especially for non-EU national immigration applications. Moreover, this statistic is influenced by the (then) quicker decisions for EU/EEA nationals resident in the UK exercising free movement rights prior to December 2020. An example of the timeframe and interactions of a client can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. a client ‘service’ journey

4. Analysis of employment data

(a) Introduction

In this paper we focus on the employment issues faced by the clients accessing the support of GYROS since, as we saw above, most EU migrants came to the UK for work purposes. Within the dataset, 50% of the clients are employed: 38% full time, 11% part time and 1.5% self-employed. Only 21% of those in the dataset were not employed, with another 27% categorised as ‘not applicable’, which denotes either those who are unable to work due to their immigration status or those whose employment status was deemed irrelevant to the issue they presented with. There are just under 250 different employers or agencies with which GYROS has interacted. The majority of those listed are employment agencies recruiting to local poultry factories including Bernard Matthews, Creswick Chicken, Banham Poultry, Gressingham Ducks, Birds Eye and Crown Chicken.

Employment queries accord with the gender split within the overall dataset, with 56% of enquiries from women and 43% from men. The mean age is 45.7 and the mean number of years in the UK is 9 years.

Further analysis of the data indicates that although just 7% of enquiries were classified as employment-related, most of the welfare benefit enquiries (26%) related to those applying for in-work benefits. This reinforces the point made earlier that most of the migrant workers are doing low-paid jobs.

(b) Support to access work

Almost half of the attendances by clients about employment concern access and support to find work (48%). Most EU migrants moved to the region to find workFootnote 12 and the case notes show that GYROS is often the first port of call for support in finding work by helping clients to create a CV or fill out an application form. A frequent feature of case notes was assistance to write and print a CV for clients to distribute to relevant employers in the town. GYROS keeps a copy of the CV on file and the database reveals some clients coming back to seek assistance to update their CV when looking for further work opportunities.

The need for assistance to prepare a CV is particularly evident from other aspects of the data, both quantitative and qualitative. 86% of the client group cannot speak English, despite the mean range of time spent in the UK being 9 years. Furthermore, as outlined by Barnard et al (2021), most clients have limited digital skills, with more than 60% of GYROS’ clients rating their IT skills as less than 5 out of 10 (10 is excellent),Footnote 13 as the following example shows:

Client has been in the UK since 2013, he was working in factory for last 3 years, but this last month they did not call him back to work. Client wanted to claim JSA [Job Seekers Allowance]. I did JSA claim online, explained to client about the CV, that he needs to sign in every other week and needs to show that he is actively looking for a job, I also explained that he will need an UJM [Universal Job Match] account. Client had no idea how to do it and he does not have an email account. I told client that I will create one for him. [Portuguese, male, working in a food processing factory, GYROS case note ID 314]

Support to write a CV goes beyond merely assisting a client in obtaining work. As a seaside town, work in Great Yarmouth is subject to seasonal variation and so periods of work are often combined with periods of accessing benefits. Jobseekers applying for (now) Universal Credit (UC) must show that they are looking for work and an up-to-date CV is required to be uploaded into a client's UC journal.Footnote 14 Within the increasing digitisation of bureaucracy of the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP), the CV becomes a vital piece of evidence which can help unlock access to benefits. Assisting with a CV might appear to be simple and non-legal, yet the CV is also an illustration of the ‘bureaucratic bordering’Footnote 15 of EU nationals: not having a CV to prove the individual is seeking a job can lead to welfare benefit sanctions, which, in turn, can lead to rent arrears and other debt issues. These administrative systems create pathways to legal problems which may arrive back at GYROS’ door to be unpicked by frontline advisers.

(c) Issues arising for those in work

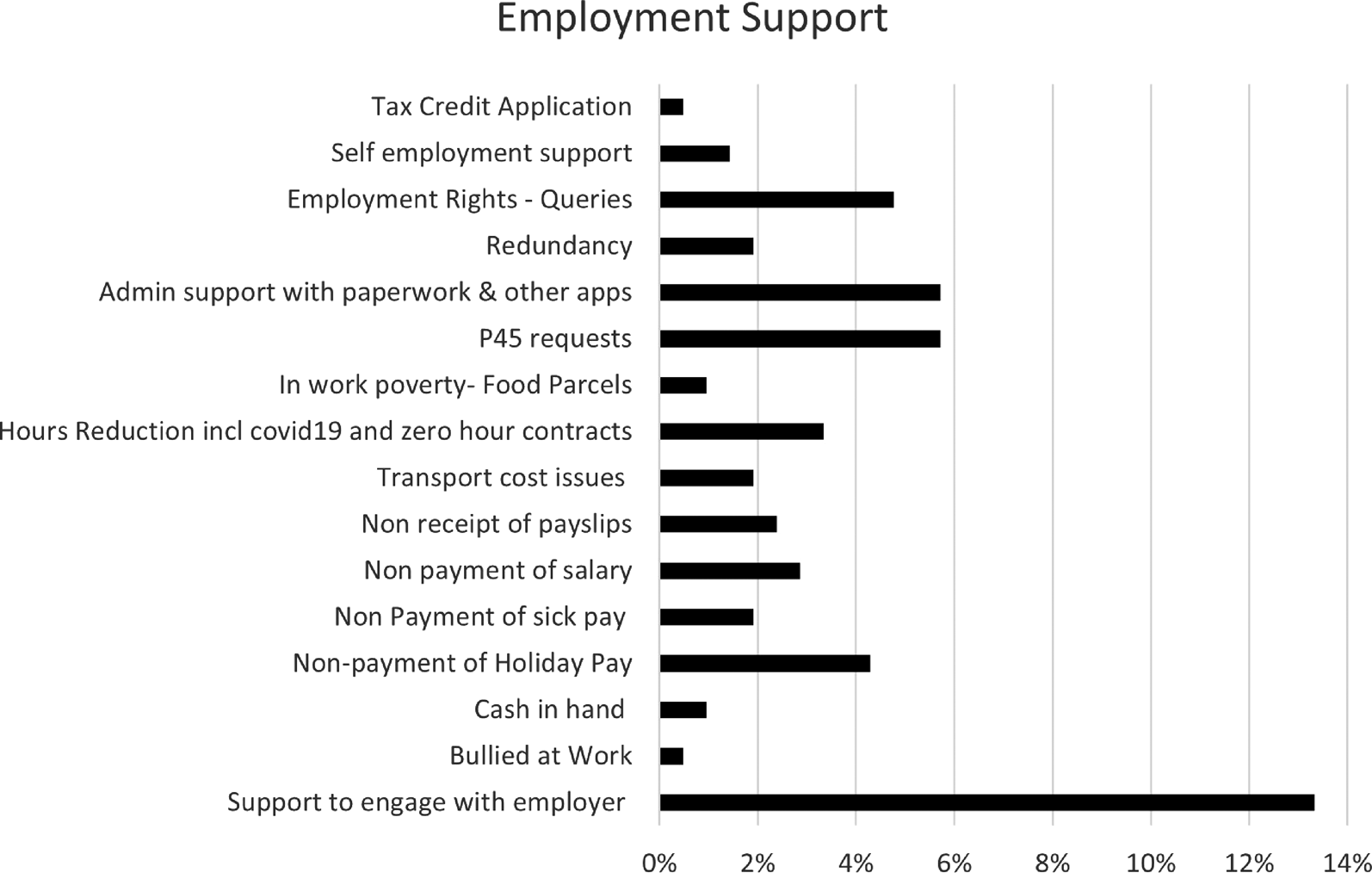

For those in work, clients access support from GYROS regarding working conditions and treatment at work. This includes (see Figure 4) non-receipt of holiday pay, sudden reduction in hours, non-payment of salary, sick pay, bullying in the workplace and non-receipt of payslips. In addition, there are a number of interactions for non-receipt of a P45 (which marks the end of employment with the particular employer) and regarding redundancy support.

Figure 4. employment queries brought to GYROS 2015–2020, based on qualitative assessment of the queries undertaken by researchers

(i) Payslips

Non-receipt of payslips appears to be relatively common, especially in some sectors and with some employers in the local area, and particularly for clients who are zero-hours contract workers. However, this issue comes up more frequently not as a direct employment enquiry but when clients are making enquiries about benefits. Clients run into problems with access to certain benefits due to the lack of payslips, but until they attempt to access benefits they may well have been largely unaware of the need to have payslips. This is a further example of bureaucratic bordering of migrant communities. GYROS volunteers and staff are very aware of this practice. Indeed, many of the GYROS staff first worked in these low-paid jobs when they arrived in the UK and experienced these problems first-hand. This case note provides an example:

Client is pregnant and due in June. Client is not employed at the moment and wanted to know if she can get MA (Maternity Allowance). I checked her test period (March 2017–June 2018) and her employment in that period. She had two jobs: from one only four payslips (August–Sept 2017) and no payslips from the other. She is not sure if she was on their books. So, she will check and come back next week to our drop in. I explained her that in order to get MA she needs to prove that she was employed for 26 weeks in her test period and provide 13 payslips from that period. [Portuguese, female, GYROS case note ID 1242]

The notes show that this client was ultimately unable to prove she had been working for the purposes of being entitled to Maternity Allowance, despite having worked throughout the relevant period.

This finding is not unique to GYROS: the 2019 ‘Unheard Workforce’ report by the London-based Latin American Women's Rights ServiceFootnote 16 said that 20% of their client group working in the cleaning, hospitality, and domestic work sectors did not receive payslips. Footnote 17

(ii) Holiday pay and salary

GYROS often writes to employers chasing non-payment of holiday pay or salary.

Client has been advised at the CAB to come to GYROS for us to help him write the letter to his employer requesting for wages to be paid. I asked the client why CAB didn't help him with the letter, he explained that he did not understand because of the language barrier. Client was under a lot of stress and overwhelmed that he couldn't get the help he needs so far, and that his dishonest employer will get away with not paying him. I wrote a letter to the employer, see attached. [Lithuanian, male, lorry driver, GYROS case note ID 86]

And sometimes to achieve an outcome, perseverance is key.

The client worked for **** and he left about 3 months ago, he received P45, but he did not receive his money for holiday. He worked there for 4 months, and he never took any holidays. He was expecting approx. 8 days of holiday, (about £400) I wrote an e-mail to the head office about his situation, and I made an appointment for him to see me next week to follow up. [Romanian, male, food delivery worker, GYROS case note ID 507]

GYROS needed to make another two appointments to see the client and contact the company repeatedly to chase this payment – the client did not receive the money until more than five months after he had finished working there.

Below is an example of GYROS helping a client to engage with their employer by gathering and submitting the correct employment paperwork to prove their entitlement to holiday pay from their employer.

02/06/2018: I contacted company again on behalf of the client regarding his holiday pay and they asked him to show evidence of … all his personal details such as payslips, NI and contract. We provided all and they said that he will receive the money in 2 weeks.

18/06/2018: The client wanted to ask why he still had not received his money. I have contacted the care line again and they said that his money will be in his account in a few hours. Client contacted us later on and informed us that he received his holiday pay into his bank account.

(iii) Understanding paperwork

Requests for help from GYROS to provide support to clients to engage with their employer or to help them understand employment-related paperwork are common. This is frequently in the form of English language support to help clients understand their employment contract or to read health and safety materials provided by the employer which they must sign. The notes show that clients will present this paperwork to GYROS and ask that they read it through for them so the client can understand it. The database also shows clients coming to GYROS for help to request time off work on, for example, the grounds of health procedures or for trips ‘home’. GYROS will normally write a letter on behalf of clients which they can present to their employer.

Client needs help to ask his employer for one week extra of holiday next January 2017 even if they do not pay for that week. Client needs to go to his home country for family reasons. I told client that I will write a letter and he can collect it next Wednesday. [Portuguese, male, factory worker, GYROS case note ID 210]

Sometimes GYROS follows this up with a phone call on the client's behalf if there is no response to the request.

(iv) Employment-related issues

The language support is not limited to explanations of paperwork. English language skills tend not to be as much of a barrier when speaking with colleagues in the workplace, as many workers report that in practice factories are informally delineated on nationality and language lines.Footnote 18 So, for example, one former recruitment agency worker told usFootnote 19:

That is how it works. I will have people that say OK that factory, they can't go there because it is a Lithuanian factory. And honestly you go there, and everyone speaks Lithuanian and maybe a few Polish, Latvian, a few Portuguese but a few only and then the rest is Lithuanian. There are many factories like that. We even had managers who said I only want Polish, Lithuanian and Latvian, I don't want any other. I couldn't believe I am actually being told by my boss – listen you employ only this this and this [nationality].

However, interaction with management can result in wider difficulties, which may again find their way to GYROS’ door:

For me for example, Thursday when I went to work in the factory – they never showed me what to do. Literally, I went there and there was a massive group of people and like supervisors coming and they go ‘you, you, you and you – Line 2’. So that is what I did because she pointed a finger at me. And then, ok so what the fuck am I doing? So, they put a basket of potatoes and scale and boxes. I am like ok. How much? 50 grams. Ok. So, the first day I am like, 50… 47, 48, 49… 50. And then she comes to me and she like mimes ‘no’ and ‘faster’ hand gestures. Not even saying it to me, not even speaking to me. ‘Faster’, ‘Faster’ (hand gestures). OK. So, I try, and it was horrible, and nobody explained to me first day – so this is what you do, you've got a scale here and you can put 40–60 grams in the box, no one told me this, so I am trying to do exactly 50g. On the second day I am told I can do 40–60g. There is no training, you are just left alone.Footnote 20 [Polish, female, former factory worker, Great Yarmouth]

(v) Health issues

Low-skilled work in the UK is characterised by low pay and, increasingly, zero hours contracts, agency work, long hours, shift work and hard, often physical, labour.Footnote 21 There is often a lack of training, because of language barriers, and under-investment in staff. There is evidence in the database of health problems caused by repetitive tasks on the factory line as well as injuries due to heavy lifting and the physicality of the work. A small number of clients in the database have made injury at work claims, with one client awarded £14,000 in compensation for a broken arm that she had sustained at work.

Client has returned back to work on part-time contract; however, she is unable to continue to work due to her health issues – frozen shoulder diagnosis. Client's doctors have suggested that client's illness is caused by her workplace. I helped client to contact a lawyer's firm to see if they would take the compensation case on, I was advised to contact Law Society as they would be able to advise of any lawyers locally who would be able to take on client's case. Client told me that she has a further appt with consultants so she will speak to them before contacting Law Society. Client will also take time off sick from work as advised by her doctor. [Polish, female, factory worker, GYROS case note ID 171]

However, such examples appear to be relatively limited.

For others, an accident at work can quickly spiral into problems elsewhere.

April Case Note: Client (anonymised as B*) suffered a hand injury at work and has been receiving statutory sick pay until recently. Since she suffered her hand injury and had to go through an operation, she had to stop working and started to suffer from financial instability. B* started to accumulate rent areas, because even though she was receiving housing benefit she still had to do a rent top-up which she couldn't afford. She received ESA (Employment Support Allowance) for a period of time but after the medical assessment that stopped. She then claimed JSA (Job Seekers Allowance) but had to be actively looking for work, which with her health condition and her low level of English has proven to be very difficult. Because of the amount of rent arrears and her inability to afford the rent, B* went to the council to get help finding a more suitable and affordable accommodation, for herself and the son that lives with her. Housing Options started to investigate her case. Because B* had a large amount of rent areas, they said that under the council policies, if B* were to become homeless, she would probably be considered to be ‘intentionally homeless’ and not eligible for support.

December Case Note: B* was taken to court by her landlord. She received an official eviction order. She has to vacate the property by the 30 January. B* was looking, but not succeeding, in finding a new property. [Portuguese national (Guinea-Bissau), female, factory worker, GYROS case note ID 783]

The cases above highlight the broader health impacts arising from the working conditions of low-paid EU migrant workers. The impact, both physical and mental, of problems that have clustered prior to a client reaching GYROS appear as an emerging theme in the data.

This accords with Hazel Genn's earlier work identifying that ‘the role of law as a mediator of the nation's health is one least well recognised, researched and understood’ and noting the bidirectional link between law and health and the ‘health harming effects of unmet legal needs’. Footnote 22

(vi) Zero-hours contracts

The database also highlights the difficulties faced by workers because of the interchangeability of workers in zero-hour contracts and precarious work arrangements. A number of zero-hours contract workers from the cohort are clients who have attended GYROS in relation to the issue of hours of work being reduced. Sickness or childcare issues regularly appear as reasons for a person to be replaced or not offered hours again. We were told by one research participant that some individuals pay line managers up to £20 cash per week in order to ‘guarantee’ their shifts, with line managers exploiting and capitalising on the precarity of zero-hour contracts:

I've got a lot of situations where people are coming to the office and it's not confirmed because no-one is going to say that, but they're coming into the office and they're shouting at us and they say no ‘my manger said I would be working all week’ and I'm like but the manager is not the one who makes this decision, we make these decisions, and then suddenly we will get an email from the manager the next day saying I want X, X and X person to work only. I'm 100% sure they are giving them money. You know, ‘then give me £20 and I will make sure you are working x5 days’. Opportunity to earn £200, then of course you pay £20.00. [Polish, female, former recruitment agency worker, Great Yarmouth]

One client (whose case was observed at the GYROS complex case meetings) had to self-isolate due to a COVID-19 outbreak in the factory and found he was offered fewer hours upon his return to work. His previous shifts had been filled by someone else while he was away.Footnote 23 Another client was told not to come back after he asked if he could have a toilet break:

Client explained he asked for a toilet break but was told by his supervisor to wait until breaktime, when the client asked again, he was told he can go, but doesn't need to come back. [Polish, male, food processing factory, GYROS case note ID 497]

The client was told by the agency's site manager to go home that day after he contacted them about the above incident. He attended GYROS the day after this and in the first instance GYROS called the agency and the client did return to work, switching to the night shift so he would not have to work with the supervisor again. Although the client was advised by GYROS to return if he wanted assistance to contact his union, it is unclear if this took place. It may be, as in many of the case notes and in discussion with the caseworkers, that clients ‘choose’ to continue to work rather than enforce their rights. We return to this issue below.

(d) Clustered problems

The data provides good evidence of what has been described by others as ‘problem clustering’,Footnote 24 namely certain problems having a propensity to cluster together, or of ‘cascading’,Footnote 25 whereby with a domino-like effect one problem leads directly to another. Typically, the commonly ‘clustered’ problems identified by research to date tend to be around work issues, rented housing, money, debt and welfare benefits.Footnote 26 This is also seen in the GYROS database. Take the case of the client above who was required to self-isolate during COVID. Due to a reduction in income, he quickly fell into rent arrears and debt. This was complicated further because he was not eligible for the UK Government's COVID support payment because he did not have a National Insurance number (NINO). He was blocked from applying for a NINO because the issuing of EU national NINOs stopped for most of 2020 due to COVID. When NINO applications re-opened, he learned he could not apply for a NINO without first applying for EU Settled Status (see below). In the meantime, he had accrued debts and had access to less work after his isolation period. He was caught in a web of paperwork which limited his access to support until he could regularise his immigration status.Footnote 27 This is a key example of internal, bureaucratic bordering adding to the bureaucratic burden experienced by migrant communities in both employment issues and other matters in terms of problem cluster creation, particularly where the inter-relationship between immigration status and employment is not recognised by the client.

Some clients do recognise the problems that can arise if they lose their job: take the case of the individual refused toilet breaks (ID 497) where it appears he chose to work rather than address the issues or enforce his rights. This could be because he is aware that access to state support was dependent on his ability to prove that he was exercising a Treaty right (such as working). In these situations, maintaining work under any conditions becomes essential to avoid descending into a cluster of related problems.

Sometimes it appears that clients do not appreciate the impact of their actions in one domain on other areas until it is too late, and this is particularly an issue in the low-paid sectors. It is only when they come to seek help that the consequences of their actions become clear:

Client said he claimed JSA (Job Seekers Allowance) and started receiving the benefit two weeks ago. Client was working for food processing factory and was paying £40 per week for transport plus £40 per week for childcare. Client stopped working because the money he was getting was not enough for him to pay his living expenses. Adviser explained to the client that he should not have left his job as the Job Centre could consider him intentionally unemployed and because of that he could be sanctioned, and his payments would stop even though he has enough contributions. Client said his adviser had already told him the payments would stop as they contacted his former employer and employer said that the client had left his work. I advised the client to get a job as soon as possible and client said he would return to the same food processing factory and had contacted them. Client needs to provide a letter advising the reason he left and refer to his transport arrangements as the cause. Client is able to get a lift for the morning shift- starts at 6.30am. GYROS will write the letter to explain to the factory why he left, and the client will come later to collect it. Client was ok with this. [Portuguese, male, food processing factory, GYROS case note ID 1347]

GYROS may step in again as an access point for food parcel vouchers, or for transport payments so they can travel to their initial induction to work or to assist with transport costs until a client receives their first week's pay.

Client left her abusive partner about 2 weeks ago and since then has been street homeless, apart from when she sold her phone to pay for 2 nights at a B&B. Client has a sister in Bulgaria who sometimes sends her some money and she can communicate with her on Skype using the Central Library computers. Client has made UC claim and has job working once a week for 10 hours. Client is worried that someone will attack and abuse her while she is rough sleeping in the graveyard. Client told me that she would like to work more hours so that she could rent somewhere. GYROS manager gave client an old phone and £10 for sim card in order for client to find employment. I helped client to get job interview at local chicken factory and we authorised £10 travel money for client to get train to an interview there the next morning. Client was very pleased and said that she feels much better now that she has a job interview. I advised client that I will call her tomorrow to make sure she is ok. [Bulgarian, female, GYROS case note ID 373]

‘Pragmatic law’ (PL)

(a) The approach taken by GYROS

GYROS takes a pragmatic, resolution focused approach in supporting clients. We wish to argue that this form of support deviates significantly from traditional legal advice models and represents what we call PL. There were examples of this pragmatism in the section above. In this section we look more closely at how this pragmatism can be seen in employment matters. So, for example, GYROS often calls the employer or agency on behalf of the client and seeks to resolve the issue directly.

Client thought he was no longer working for (Agency) and wanted to know why he did not receive P45. I called to main office to speak to the agency directly and administrator informed that client is still employed, and he still has outstanding holiday pay. Client did not know he was still employed as he hasn't been called for any shifts. Said he will then try to get some work with them, if not he will come back if he needs to in order to request P45. [Lithuanian, male, food processing factory, GYROS case note ID 485]

Alternatively, GYROS’ assistance might be to support a client to find a new job:

Client has been working for employer for three years without any payslips. He thinks if he approached his employer to ask for payslips he will be fired. Client instead is seeking support to apply for a new job and would like help with a CV and to complete an application form. Children's services are involved with the family due to their current financial situation; family are in receipt of food parcels and have been unable to fully furnish their rented property. Client is struggling to apply for UC due to lack of paperwork. [Romanian, male, food processing factory, GYROS case note ID 163]

The case notes reveal that GYROS supported the client into a new job, helping him write a CV, fill out the application form and even phoning the new company on his behalf. He was at an induction the day after he came to see GYROS. Once he started to work, GYROS helped the client to apply for Universal Credit (UC). In time, the notes show, the family's income regularised and children's services involvement was no longer needed. The notes do not record anything being done regarding the original employer who refused to provide payslips. For GYROS, the most pragmatic approach was to help the family into regular documented work and to apply for UC. As with several examples in the database, pragmatism prevailed – this family needed help to put food on the table and furniture in their house, and to meet their children's care needs and children's services requirements to be satisfied. The quickest way for the client to access welfare benefits was by showing that he was exercising his right of free movement, and that meant a job with the right paper trail.

So beyond simply ‘advice’ for many clients, GYROS acts simultaneously as advocate, translator,Footnote 28 donor (eg in relation to money, phone), and brokerFootnote 29 (or all four) in their employment relationships, depending on what is needed. Parallels can be drawn here with other research outlining the role of ‘community brokers’ who translate and navigate sometimes ‘Kafkaesque documentation’Footnote 30 and ‘a labyrinthine multiplicity of different agencies’Footnote 31 on behalf of those they are helping. Koch and James (2020) define the role of ‘community brokers’, below.

In marginalised settings, where ‘basic’ goods and services are difficult to access or outright unavailable to large swathes of citizens, it is often only with the help of these brokers that citizens can make their demands for housing, employment benefits or immigration-related resources heard. Brokers who move between their clients and the institutions, authority figures and actors that their clients struggle to access, occupy a veritable in-between position, deriving their legitimacy from their seeming proximity to the ‘common people’ while also possessing specialist skills and knowledge that the latter lackFootnote 32.

In translating and explaining employment contracts and related documentation, GYROS plays a trusted role for clients who rely on them so that they may enter a legally binding contract with their employer, or to sign confirming the client understands the health and safety responsibilities at work. This trust, and GYROS’ legitimacy with the clients it works with, is gained through the cultural and biographical proximity of the advisers to the clients, and the fact that the advisers live in the same communities and speak the same languages as their clients and have often followed the same migration pathways into the UK.

The multi-faceted response by GYROS is appreciated by its clients. From August 2019 to August 2021, GYROS received 2166 service feedback forms from clients accessing services.Footnote 33 In this time 83.6% of GYROS clients rated the service they received as 10/10, with a further 1.4% rating it at 9/10 and 1% at 8/10. This means that 86% of clients rate the service at 8/10 or more. The lowest rating was 5/10 and this was from two individuals, one of whom stated the reason for the low score was that they hadn't received their EUSS status yet from the Home Office (ie not due to any failing of GYROS). Of the service feedback forms received (n = 2166), 13% did not complete this question. While this data shows that clients rate very highly the service they receive from GYROS, one limitation to this is that it is collected by GYROS advisers who have just provided the service to the individual being asked for feedback. Here, the client completes a paper feedback form, translated into their own first language, on their own (unless there are literacy issues) and hands it back to their adviser.

(b) ‘Pragmatic law’ (PL)

This paper is our first analysis of the substantial GYROS dataset. The cases in the dataset provide a window on the lived experience of law of low-paid migrants, seen through the lens of a community advice agency. By understanding what issues migrant communities are facing, what problems they are accessing support for, and how these problems are being resolved by frontline, first-tier community advisers and brokers, we can explore what happens in real life to help us understand the role of the law in society. While lawyers view a legal system which places the highest courts at the apex of the legal enforcement pyramid, in reality ‘very few legal problems see a lawyer and fewer still see a courtroom’.Footnote 34 What our study shows is that at least among the cohort we are looking at, many do not access formal legal advice for their problems. Rather, they go to GYROS to seek practical resolution of their problems. The problem resolution is often pragmatic (anti-bureaucratic) and multi-faceted.

Research shows that it matters whether individuals recognise their problem as legal.Footnote 35 People who do not see their problem as ‘legal’ are less likely to access legal advice.Footnote 36 Further, Hazel Genn tells us that problem categorisation swamps all other categories.Footnote 37 In this way the legal consciousness of both the individual accessing the advice and the adviser dispensing advice is relevant to the categorisation and resolution journey of (legal) problems. In our data, it is unclear whether clients see their problem as legal. But we do know that they have not sought legal advice for their problems, turning instead to GYROS (who may, in rare cases, direct them to lawyers (eg ID 171)).

Further, GYROS works in a recognised legal aid desert,Footnote 38 with the nearest availability for free legal advice services in Norwich in Norfolk (with some monthly outreach available in towns) and Ipswich in Suffolk. These free legal advice services can offer 20 minutes of free advice from volunteer solicitors; services are often overwhelmed.Footnote 39

‘Pragmatic law’ looks at problems which do not make it even to a law centre. It is the problem resolution and approach offered by GYROS and other community advice agencies working every day to support vulnerable communities with (sometimes) complex (legal) problems. In this way, ‘pragmatic law’ provides a framing for both: (1) the lived experiences of migrant communities; and (2) the approach one particular agency, GYROS, takes to resolving those problems. Understanding the problems that are experienced and the means by which they are resolved, allows a bi-directional analysis. It provides a thicker and more comprehensive understanding of everyday (legal) problems and dispute resolution. It shines light on the world of the law, outside the formal structures of the legal system. It also helps us to understand why enforcement levels of rights through defined pathways, within the formal legal structure such as employment tribunals, are so low.Footnote 40

Conclusions

This paper examines one element of the substantial database of GYROS, a community advice agency, to identify the issues and trends of the problems faced by low-paid migrants in one of the most deprived parts of the UK, Great Yarmouth. It also develops our framing of how to consider and analyse the resolution mechanisms deployed by GYROS to deal with their clients’ problems. We are not trying to generalise the experiences of the cohort we are working with, but we think it provides a useful case study of vulnerability.

In respect of GYROS’ clients, we have shown how employment problems can quickly become housing problems and welfare problems. This clustering of problems is familiar to many of those who are poor, but for EU workers their vulnerability is now exacerbated by their migrant status in the UK and latterly by the advent of the EU Settlement Scheme. Those in and around Great Yarmouth are fortunate to have access to an organisation like GYROS. It is striking that GYROS’ role does not just provide (legal) advice, but it also acts as pragmatic anti-bureaucrat, translator, donor, trusted community resource and broker. It offers a client-need driven service, sometimes undertaking all these roles at once, dealing with a multiplicity of clustered problems simultaneously, strategising which problem(s) are most urgent and working from there. This approach seems to be appreciated by the users.

This multi-dimensional resolution approach does not fit with traditional legal models of specialisation – such as family law or criminal law.Footnote 41 While GYROS will refer to specialist support where that can complement the work it is doing, GYROS often acts as a safety net. It becomes a ‘one-stop shop’ for many clients, taking a deeply pragmatic and problem-solving approach without necessarily engaging with the formal ‘legal’ issues. This approach differs very much from the formal dispute resolution taught in law schools. It is a very different approach to law. We term the approach ‘pragmatic law’.

Existing literature does not appear to capture the approach taken by GYROS (and presumably other similar organisations) to problem resolution. We are therefore developing the notion of ‘pragmatic law’ to try to describe the role that street-level advice plays in (legal) problem resolution, usually without recourse to access to justice. We hope this provides a thicker understanding of the role of law as it plays out in the everyday lives of people, specifically in our case, EU migrants in East Anglia, and how they and their advisers respond to their problems.