In a democratic society, police are expected to respect citizens' due process rights and to ensure order in society. From the standpoint of the police on the beat, competing demands to ensure due process and social order are embodied in the fiber of their work day by day. In this context, the line between the legitimate role of ensuring social order and the illegitimate role of engaging in misconduct may blur. For example, from the vantage point of an officer at work, the reminder to the victim of who is in charge by, perhaps, the use of strong or even vulgar language, some threatening remarks, or the use of unnecessary force may be viewed as an essential part of one's toolkit (Reference Skolnick and FyfeSkolnick & Fyfe 1993); that is, there may be times when “dirty means” are justified to ensure worthy ends. Findings from observational studies of policing corroborate a blurry distinction between the tasks of preserving social order and misconduct and, also, demonstrate a strong tradition of “street-level” discretion guided by what is considered “extralegal” or circumstantial considerations (Reference Mastrofski, Reisig and McCluskeyMastrofski, Reisig, & McCluskey 2002; see also see Reference Black and ReissBlack & Reiss 1967; Reference KlingerKlinger 1994, Reference Klinger1997; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2000; Reference Worden and ShepardWorden & Shepard 1996; Reference MuirMuir 1977).

Research suggests that most citizens tend to place a great emphasis on an expectation of evenhanded or trustworthy practices (Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002). The public expresses a rather low tolerance for police misconduct, particularly the unnecessary use of force. When asked about such behavior, findings show that, in principle, 93% of respondents do not approve of an officer “striking a citizen who had said vulgar and obscene things to the officer” (National Opinion Research Center 1998, 2000; also see Reference GallupGallup Poll 1999; Reference HarrisHarris Poll 1999; Reference SchwartzSchwartz 2002). The claim that police officers should toe the line and perform their jobs within circumscribed, fair processes suggests that the public expects officers to behave like professionals. In the popular sense of the term, police professionalism translates into an expectation that officers will perform their duties within a set of fair, public, and accountable guidelines.

Indeed, the push for more accountable, or more professional, police practices has a long history, including attempts to elevate the educational requirements of officers to continuing training programs (Reference Black and ReissBlack & Reiss 1967; Reference Walker and WrightWalker & Wright 1995). This article focuses on one such effort: the introduction of administrative guidelines to define misconduct as it relates to officers' interactions with civilians. In New York City (the site of this study), as is true elsewhere, prohibited behavior by police is captured by the acronym FADO: the use of unnecessary Force, Abuse of authority, Discourtesy, and Offensive language (Reference HenriquezHenriquez 1999; Reference Walker and WrightWalker & Wright 1995).

The goal of this article is to understand how the public weighs “legal” and “extralegal” factors in judging the seriousness of misconduct, or FADO. Studies of the public's view of FADO have not, to date, allowed respondents to judge officers' behavior in the context in which such incidents typically occur, including, for example, a civilian's suspicious behavior or a rude or confrontational demeanor. Given the opportunity to judge police misconduct, the public may demonstrate a collective judgment that derives from an expectation that following legal guidelines is most important and that recognizes the place of possibly mitigating, extralegal circumstances, or some combination of both.Footnote 1 To give an example, an encounter between an officer and a civilian might read:

A police officer stops a Jamaican, teen male because a bulge in his waistband might be a gun.

The civilian demands to know why he is being stopped and repeatedly tells the officer, “I know my rights.” The police officer calls the teen a “fucking wise ass” and places a hand on his gun. The teen attempts to leave the scene. Later, the police officer slaps the teen with an open hand. The teen physically resists the police officer. The police officer says he found the teen completely disrespectful.

As a result of the interaction, the teen suffers mental trauma and the police officer receives minor injuries.

In this encounter, the officer's behavior technically violates FADO guidelines: He uses offensive language (calling the civilian a “fucking wise ass”), abuses his authority (places a hand on his gun), and uses unnecessary force (slaps the teen with an open hand). The extralegal, or mitigating, evidence may, however, complicate judgments about the seriousness of these technical violations: The status of the civilian may imply stereotypical expectations of behavior from a minority, male teen; the civilian's demeanor may be construed as confrontational (“demanding” to know why he is being stopped or physically resisting the officer); the police officer reports that he found the teen “disrespectful;” and, finally, both the officer and the teen suffer a degree of injury. Together, the “facts” of the officer's behavior are to be judged in the context of a likely set of mitigating factors that may, or may not, complicate citizens' judgments. Does the legitimacy of police practices derive principally from adhering scrupulously to “clean means,” or can police sustain their legitimacy by calibrating the response to the “situational exigencies” that Reference BittnerBittner (1970) claimed are the determining features of how police exercise their authority?

To explain the public's judgment of police misconduct, this article reports findings from a survey of New York City residents asking respondents to rate an officer's misconduct on a seriousness scale, where zero is no misconduct and ten is serious misconduct. The instrument used in this study incorporates a factorial survey design (Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and NockRossi & Anderson 1982), a technique well-suited to obtaining judgments from a large population regarding a complex social phenomenon. In the research reported herein, the complex social phenomenon is police misconduct. Because the factorial design allows respondents to answer questions in the context of an encounter described in considerable detail, it is designed to help explain whether and to what extent respondents share a common, normative understanding of the boundaries, seriousness, and thresholds of police misconduct, or FADO.

This article is divided into five sections. “Dimensions That Affect the Judgment of the Seriousness of FADO” presents a rationale for selecting dimensions of a police-civilian interaction to capture FADO that is designed to weigh the role of legal guidelines as well as the role of extralegal or circumstantial exigencies such as the reason for the encounter, civilian demeanor, or an injury to the civilian or the officer. “Respondent's Background” considers the ways in which a respondent's background, including social status, political orientation, and prior experience with the police, may shape judgments. “Research Design” describes the research design of this study. “Findings” reports the results of our research, focusing on the significant dimensions in an explanation of citizens' judgments of police misconduct. In the conclusion, we turn to a discussion of the implications of the findings.

Dimensions That Affect the Judgment of the Seriousness of FADO

A key first step in the design of a factorial survey is to devise a vignette template consisting of the characteristics of the social object being studied. A vignette template is composed of a series of dimensions that capture a sequence of events that order the description of the social phenomenon under investigation, in this case FADO. In this study, dimensions include incidents of FADO as well as the circumstantial factors that place the event in context, such as the mobilizing event or reason for the stop, the social status of the civilian, and his or her demeanor toward the officer. Within each dimension, levels capture the texture of the vignette. For example, a level of the dimension discourtesy/offensive language might read, “The police officer cursed at the civilian.”

The dimensions and levels of police–citizen encounters were constructed based on a review of the literature of observational studies of policing, an analysis of a random sample of closed and redacted cases that were filed with the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) of New York City in 2000, and two focus groups with in-take officers at the CCRB. These three sources enabled the authors to identify the key dimensions and levels usually present in actual cases of alleged police misconduct.

Table 1 presents a summary of the dimensions and categories of levels used to describe a police-civilian encounter as well as the expected impact of categories of levels within dimensions. First, we consider the dimensions of FADO that are designed to capture the legalistic factors of a police-civilian encounter as it possibly escalates toward misconduct;Footnote 2 we then consider the dimensions ranging from the mobilizing event to social status, civilian demeanor, police authority, and injury that are designed to capture the extralegal factors of a police-civilian encounter.

Table 1. Summary Description of Vignette Template, by Dimension and Expected Impact

×=No Effect, −=Negative Effect, +=Positive Effect

FADO: The Dimensions of Police Professionalism

Professionalism implies a multifaceted value orientation, including trust by clients that is based on the professional's schooled expertise and commitment to rules of ethical behavior.Footnote 3 In response to public demands for greater accountability of the police, municipalities have taken steps to reform administrative, or legalistic (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995) guidelines that define and resolve issues of alleged police misconduct and that serve, in many respects, as an equivalent for police professionalism (Reference Cao and HuangCao & Huang 2000; Reference Skolnick and FyfeSkolnick & Fyfe 1993; Reference WalkerWalker 1995; Reference Walker and WrightWalker & Wright 1995).

Discourtesy/Offensive Language

As a general matter, municipal guidelines require that officers remain polite and respectful in their interactions with civilians; officers are also required to avoid the use of offensive language, including vulgarities and ethnic slurs (CCRB 1993). In developing the vignette template for this study, we learned from a review of cases filed with the CCRB that the vast majority of alleged instances of police misconduct begin with a claim that the officer was disrespectful or used offensive language (also see Reference TerrillTerrill 2001). The vignette presented in the introduction demonstrates this point, when the officer calls the teen a “fucking wise ass.” For the purposes of this study, therefore, discourtesy/offensive language is treated as a baseline dimension and appears in all vignettes.

What constitutes discourtesy or offensive language is not, however, without ambiguity. This may be especially complicated in an era of community-oriented policing, when officers are encouraged to get to know their beat and the people who live there (Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and ParksMastrofski, Snipes, & Parks 2000; Reference SkoganSkogan 1994; Reference TerrillTerrill 2001). For example, an officer may be a bit proactive or use some mildly strong language in an effort to give advice “or attempt to persuade a citizen” to toe the line or to comply (Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and ParksMastrofski, Snipes, Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and Supina& Parks 2000:307; Mastrofski, Snipes, & Supina 1996). Thus, within this dimension, a number of levels are constructed to suggest advice to discontinue some illegal behavior, to leave someone alone, or to calm down; an example of this level states, “be careful, you can get arrested for that” (also see Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and ParksMastrofski, Snipes, & Parks 2000; Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and SupinaMastrofski, Snipes, & Supina 1996:280).Footnote 4 It is expected that citizens will not judge the presence of these very benign statements of advice to be serious, or for that matter significant. Beyond this, however, officers' language may be implicitly (e.g., using a racial or ethnic slur) or explicitly (e.g., telling the civilian to “shut the fuck up”) offensive. It is expected that when such levels of offensive language appear alone in a vignette (i.e., without abuse of authority or unnecessary use of force), citizens will judge them to be significant (in a statistical sense), but these levels will impact judgments to a relatively small degree.

Abuse of Authority

Our review of CCRB cases shows, however, that alleged misconduct often escalates into behavior that is claimed to be abusive or unnecessarily forceful; as the vignette in the introduction demonstrates, the officer's possible misconduct moves from offensive language directed at the teen to placing his hand on his gun. Officers are prohibited from threatening civilians (e.g., moving to place a hand on a gun) or from violating rules (e.g., refusing to provide a name and badge number when asked by a civilian); also, from the standpoint of police guidelines, abuse of authority is considered to be a more serious form of misconduct than discourtesy/offensive language. Thus, it is expected (1) that discourtesy/offensive language will be judged to be insignificant in the presence of abuse and (2) that the presence of abuse of authority, whether it involves threatening civilians or avoiding guidelines, will be judged to be significant and relatively more serious than discourtesy/offensive language.

Unnecessary Use of Force

Finally, alleged cases of misconduct may escalate to include unnecessarily forceful behavior, including pushing, punching, or beating the civilian; as in the vignette in the introduction, the officer slaps the teen with an open hand. Police guidelines treat such behavior as an even more serious form of misconduct than either abuse of authority or discourtesy/offensive language. At the same time, judgments by citizens about unnecessary force may be especially complex, whatever the mitigating circumstance. On the one hand, “the world inhabited by cops is unkempt, unpredictable and sometimes violent” (Reference Skolnick and FyfeSkolnick & Fyfe 1993:94), often rendering the boundary between unnecessary force and an officer's job to ensure compliance or deterrence blurry. Nonetheless, recent observational studies suggest that an officer's decision to make an arrest tends to be guided by a more reform-oriented set of standards (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995), suggesting a trend toward more professional policing than earlier studies document (Reference BlackBlack 1980; Reference Black and ReissBlack & Reiss 1967). Despite the ambiguities posed by the demands of policing and in keeping with the spirit of reform efforts, it may be expected that as a police officer's behavior relies on the unnecessary use of force, citizens' ratings of misconduct will increase, net of all other dimensions.

Police professionalism translates into a legalistic policing, or doing the job by the rules (Reference MuirMuir 1977:225–63). Studies of the social psychology of law demonstrate that citizens are motivated to obey authorities, including police, when there is a demonstration of “procedural justice” (Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002). Thus, even if the encounter is initiated because of some illegal behavior on the part of the civilian or if the civilian's demeanor becomes confrontational, there is an expectation that it is the officer's responsibility to remain professional, or in this case, that the officer will avoid FADO whatever the pressures of the moment.

Surrounding Circumstance: The Dimensions of “Street-Level” Discretion

While Reference WeberWeber (1947) claimed that bureaucratic rules ensure efficiency and accountability, a host of studies demonstrates that “street-level bureaucrats” often enjoy enormous discretion (Reference LipskyLipsky 1980). Rules can be placed on the books to limit and guide police action on the street, but “no matter how far we descend on the hierarchy of more and more detailed formal instructions, there will always remain a step further down to go, and no measure of effort will ever succeed in eliminating, or even in meaningfully curtailing, the area of discretionary freedom of the agent whose duty is to fit rules to cases” (Reference BittnerBittner 1970:4). A large body of observational research on policing corroborates the centrality of discretion to an officer's responsibility for getting the job done (Reference Alpert and DunhamAlpert & Dunham 1998; Reference Alpert and SmithAlpert & Smith 1994; Reference BittnerBittner 1970; Reference Cao and HuangCao & Huang 2000; Reference GellerGeller 1983; Reference Greenfield, Langan, Smith and KaminskiGreenfield et al. 1997; Reference Klockars, Geller and TochKlockars 1996; Reference ReissReiss 1968, Reference Reiss1971; Reference SkoganSkogan 1994; Reference Son, Tsang and DavisSon, Tsang, & Davis 1997).

Recent reforms to introduce a model of community policing actually embrace street-level discretion: officers are called on to be problem-solvers or to engage in community-building activities in an effort to stop crime before it happens (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995; Reference SkoganSkogan 1994). In New York City, a spirit of community-oriented policing is captured in the phrase “Courtesy, Professionalism, Respect” that appears on all police cars.Footnote 5 While some debate exists among advocates of a community-policing model about what it means in practice, the consensus is that in order to be successful, officers must do more than their legalistic job descriptions define. But, as Mastrofski and his colleagues ask with regard to a study of arrest, this “raises questions about whether and which extralegal influences might assume a larger role in shaping arrest decisions” (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995:541; also see Reference Terrill and MastrofskiTerrill & Mastrofski 2002).

To capture these circumstantial, or extralegal, factors, we include dimensions that describe the mobilizing event, the social status of the civilian, the demeanor of the civilian, the officer's authority to behave as he or she did, the civilian's injury, and the officer's injury. Table 1 shows the extralegal dimensions and categories of levels of the vignette template used in this study.

Mobilizing Event

Observational studies of policing show that in most instances, officers are “reactive” (Reference BlackBlack 1980, italics added); that is, encounters are generally initiated by citizens who request the services of an officer (Reference Black and ReissBlack & Reiss 1967; Reference ReissReiss 1971). Findings suggest that this pattern of reactive policing persists in an era of community-oriented policing (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995; Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and ParksMastrofski, Snipes, & Parks 2000). A call comes into a precinct and an officer likely gets only the most ambiguous information; while judgments may be made based on a location, in general relatively little is known (Reference BlackBlack 1980; also see Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995). “The police must move continually from setting to setting where the scenery, the actors, and the plots are frequently defined in very general and ambiguous terms such as ‘family trouble,’‘see a man about a complaint,’ or ‘take a B[reaking] & E[entering] report’” (Reference Black and ReissBlack & Reiss 1967:8; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002:6).

However, “police officers who are not busy responding to calls are free to do largely as they please” (Reference BlackBlack 1980:19) and, in some instances, do initiate “encounters on their own authority,” a strategy that is “proactive” (Reference BlackBlack 1980:87, italics added). Of course, an officer is required to be proactive when he or she observes illegal behavior—for example, a civilian walking down the street with an open bottle of liquor. In addition, situations may be highly ambiguous, as with the vignette in the introduction where the teen may or may not be carrying a gun. Whereas observational studies demonstrate that officers tend to be more reactive, a review of filings with the CCRB suggests that complaints tend to be sparked by what is perceived to be more “proactive” policing, especially, for example, being stopped on the street for no apparent reason or being asked, “What are you doing?” (also see Reference BlackBlack 1980:12). Given the responsibility of officers to ensure social control through compliance and deterrence (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, & Snipes 1995) as well as the expectations of community-oriented policing to grant officers somewhat greater discretionary authority to get a handle on extralegal factors on their beats, it is not surprising that complaints are somewhat more likely when the officer's behavior is at least perceived to be proactive.

To capture the range of mobilizing events for the purposes of this study, we rated levels that range from scenarios that describe reactive policing, such as responding to a 911 call for help, to quite ambiguous scenarios, such as a civilian walking down the street with a bulge that may be a gun or a cell phone, to proactive scenarios, or mobilizing events where the civilian is engaged in illegal behavior, such as jumping a turnstile in the subway. When police misconduct follows on the heels of a reactive mobilizing event, or events when a citizen calls for help, it may be expected that such circumstantial information will significantly increase ratings of seriousness. However, when what might be labeled technically as police misconduct follows from ambiguous situations or reactive policing, citizens may judge events quite differently: In such circumstances, it is likely that citizens will rate the seriousness of the misconduct significantly lower.

Social Status

When an initiating event is reactive, in many instances officers have few clues beyond the caller's address; information about the caller's social status, age, gender, and especially race or ethnicity may only become obvious further into an encounter (Reference BlackBlack 1980).Footnote 6 Of course, in face-to-face encounters, or when the civilian is being stopped for some reason, the social status is revealed with the event itself. Whether in the moment or slightly delayed, mobilizing events include some social status cues that the officer may register, including the (1) ethnicity/race, (2) age, and (3) gender of the citizen (Reference Fagan and DaviesFagan & Davies 2000; Reference FeaginFeagin 1991; Reference ReissReiss 1968, Reference Reiss1971; Reference Skolnick and FyfeSkolnick & Fyfe 1993).Footnote 7 Findings show that young black men are significantly more likely to report being stopped by officers than their white counterparts (Reference Greenfield, Langan, Smith and KaminskiGreenfield et al. 1997; Reference Langan, Greenfield, Smith, Durose and LevinLangan et al. 2001). Observational studies of policing show that female civilians are less likely to be arrested than male civilians, that young male civilians are more likely to be arrested than older male civilians, and that the race of the civilian has no significant effect (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, Reference Terrill and Mastrofski& Snipes 1995:351; Terrill & Mastrofski 2002:236; but see Reference Riksheim and ChermakRiksheim & Chermak 1993:365–6). Thus, the patterns that are gleaned from self-reports for the role of race/ethnicity during stops are somewhat different from the likelihood of arrest gleaned from observational studies. Further complicating the picture, media reports have highlighted concerns about racial profiling, particularly in the aftermath of 9/11, and they suggest that citizens may be more attuned to possibly disparate treatment of minorities (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2002). Despite the complicated dynamics of race and citizens' judgments, when vignettes involve young men, regardless of race/ethnicity, it may be expected that respondents will significantly reduce the level of seriousness of an officer's misconduct.

Civilian Demeanor

The citizen contributes to the interaction by his or her initial demeanor toward the officer; regardless of how the officer sets the stage, the citizen contributes as well, taking what might be interpreted as polite or confrontational language or behavior (Reference TerrillTerrill 2001)—demanding to know why he is being stopped, as the example cited earlier shows. Indeed, a long line of observational research has consistently shown that a “citizen's failure to defer to police authority is well established as a predictor of police sanctioning behavior” (Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and ParksMastrofski, Snipes, & Parks 2000:314; also see Reference KlingerKlinger 1994, Reference Klinger1997; Reference Mastrofski, Reisig and McCluskeyMastrofski, Reisig, & McCluskey 2002; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2000; Reference Worden and ShepardWorden & Shepard 1996). Building on these findings, levels of civilian demeanor capture politeness (e.g., cooperates with the officer), hostile language (e.g., curses at the police officer), confrontational behavior (e.g., attempts to leave the scene), or illegal behavior (e.g., flees from the officer, dropping drugs). Because civilian demeanor may recur in more complex vignettes (i.e., those involving more than one dimension of FADO), it is included at multiple points in the vignette template.

The relationship between civilian demeanor and the seriousness of FADO raises a complex question. From a purely legalistic perspective, officers are required to avoid FADO in the execution of their responsibilities. But viewed from the standpoint of a police officer on a beat, and particularly an officer on a beat where emphasis is given to community policing and an understanding of community “preferences,” there is the “possibility that [civilian demeanor] will become more influential, reflecting community biases” (Reference Mastrofski, Worden and SnipesMastrofski, Worden, Reference Terrill and Mastrofski& Snipes 1995:542; Terrill & Mastrofski 2002). It is expected that respondents will judge vignettes as involving significantly less serious misconduct when civilian demeanor includes hostile language, confrontational behavior, and illegal behavior at least once in the vignette.

Police Authority

Having moved to the level of force, an officer may feel the need to “stay ahead of the ‘force curve’” (Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002:199). That is, the officer may have the opportunity to explain his or her use of police authority because, for example, the citizen was completely disrespectful or resisted the officer's initial command, in the officer's view. It may be expected that an officer's claim that a citizen was disrespectful or resistant will significantly reduce respondents' ratings of the seriousness of police misconduct.

Injury to Citizen and Officer

Finally, the officer or the citizen may or may not be injured. A review of CCRB filings showed that injury to the civilian was often associated with substantiation of the, FADO claim. It may be expected, therefore, that respondents will also be more likely to observe serious misconduct when it involves injury to the victim. However, in a situation where a police officer is injured, it is anticipated that such an event would serve to reduce the public's judgment that serious misconduct occurred.

In sum, the design of the vignette template for this study captures dimensions of police professionalism, or the legalistic dimensions of FADO, and street-level discretion, or the extralegal dimensions of the surrounding circumstances of the encounter. This question arises: Do citizens judge seriousness through a lens of professionalism that gives greater relative prominence to FADO net of the surrounding circumstances, through a lens of street-level discretion that gives prominence to possibly mitigating or surrounding circumstances, or to some combination of both?

Respondent's Background: Social Status, Political Orientation, and Prior Experience With the Police

While vignettes, like actual interactions, may carry ambiguities, a judgment must be made, and each dimension of an encounter may affect how the respondent interprets the event, as the above discussion suggests. Equally, each respondent brings his or her own experiences to the table that may in turn affect judgments of the seriousness of misconduct. In this study, we consider the relative effect of respondents' social status, political orientation, and prior experience with the police on judgments of the seriousness of misconduct.

Social Status of Respondent

Variables include demographic indicators of the respondent such as age, race, gender, income, and education (Reference WolfgangWolfgang 1985; see also Reference Adams and MaxwellAdams 1999b:65). Research shows that minorities tend to reside in neighborhoods with higher rates of crime and poorer social services (Reference Sampson and BartuschSampson & Bartusch 1999). Of late, America's cities are experiencing unprecedented levels of immigration and, with it, unprecedented levels of ethnic diversity.Footnote 8 Immigrants come from diverse backgrounds, speak a variety of languages, differ with respect to the perceived quality of neighborhood services including policing (Reference Alpert and DunhamAlpert & Dunham 1988; Reference SkoganSkogan 1994), and may not share a common set of expectations about the role of police in society. Whether and to what extent police officers' actions are systematically and disproportionately more likely to be directed at young, minority males remains, as discussed earlier, a point of some disagreement in the current literature.

Other findings suggest that minorities, and blacks in particular, do not hold significantly different attitudes or expectations about issues related to the administration of the criminal justice system than whites. In a study of attitudes toward federal sentencing guidelines, Reference Rossi and BerkRossi and Berk (1997) find that the race of the respondent has no effect on judgments of a fair sentence for a federal crime. Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo (2002) find that whites and blacks report essentially the same set of procedural expectations in dealings with the police; that is, “both groups focus on whether they experienced procedural justice and whether they could trust the motives of the authorities with whom they are dealing” (2002:207). Tyler's work suggests that whites and blacks seem to apply very similar standards in judging various aspects of police performance on police legitimacy (Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine & Tyler 2003).

Against this backdrop of an increasingly rich racial and ethnic diversity of background, expectation, attitude, and experience, evidence suggests that class and education are and remain a more divisive axis in American society (but see Reference Sampson and BartuschSampson & Bartusch 1999). For example, Reference Rossi and BerkRossi and Berk (1997) do find that education has a significant impact on judging a fair sentence for federal crime, where those with less education are significantly more likely to impose a lesser sentence than more educated citizens. Testing Wilson's hypothesis that there is a declining significance of race in American society, Weitzer and Tuch (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2000; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 1999; Reference WilsonWilson 1980, Reference Wilson1987) find a complex picture about the relationship between class and race in the context of criminal justice. Whereas whites see the world in a “colorblind fashion” (also see Reference Seron, Frankel, Muzzio, Pereira and Van RyzinSeron et al. 1997), “irrespective of income and education, Blacks tend to lack confidence that the police treat individuals impartially in their communities” (1999:13; also see Reference Fagan and DaviesFagan & Davies 2000; Reference FeaginFeagin 1991; Reference Hagan and AlbonettiHagan & Albonetti 1982; Reference Johnson, Farkas, Bers, Connolly and MaldonadoJohnson et al. 1999; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 1999; Reference Wortley, Macmillan and HaganWortley. Macmillan, & Hagan 1997; Reference WolfgangWolfgang 1985). Based on prior research, it is hypothesized that

1. Respondents with more education will judge police misconduct more seriously than those with less education.

2. Respondents with lower income will judge police misconduct more seriously than those with higher income.

3. Blacks and Latinos will judge police misconduct significantly more seriously than whites, net of education and income.

Political Attitudes of Respondent

Citizens' willingness to grant discretionary authority to the police may be influenced by their (1) general attitudes toward the institutions of governance, (2) specific attitudes toward police discretion and use of force, and (3) attitudes toward the relationship between the problems of crime and minorities. The legitimacy of government is fundamental to the functioning of democratic institutions, a point made particularly clear in the work of Reference WeberWeber (1947). Legitimacy rests on a citizen's “trust in authorities” to do the right thing, “a willingness to accept” authoritative decisions, and “feelings of obligation to follow rules that authorities implement” (Reference Tyler and DegoeyTyler & Degoey 1995:483). In a democratic society, where political debate is fundamental to the legitimacy of governance, citizens bring different attitudes toward the appropriate scope of government authority to ensure social control. Whereas liberals emphasize the protection of civil liberties in the execution of social control, conservatives emphasize the importance of investigating and containing crime (Reference Rossi and BerkRossi & Berk 1997). In addition to respondents' general political orientation, they bring specific attitudes toward the police's authority to act with latitude or discretion (Reference Kerstetter, Geller and TochKerstetter 1996:241) and to engage in the use of force as needed (Reference Rossi and BerkRossi & Berk 1997:195; also see Reference Flanagan, Vaughn, Geller and TochsFlanagan & Vaughn 1996; Reference Gamson, McEvoy, Short and WolfgangGamson & McEvoy 1972; Reference Hader and SnortumHader & Snortum 1975). It may be expected that liberals are significantly more likely to judge police misconduct seriously than their conservative counterparts.

Experience of Respondent With Police

Research has shown systematic and significant differences in experience of the criminal justice system by racial and ethnic groups (see, e.g., Reference DeckerDecker 1981). Recent questions have also been raised concerning the impact of racial and ethnic profiling, where minorities are systematically more likely to encounter the police for questioning because they fit an allegedly suspect category (Reference Barnes and GrossBarnes & Gross 2000;“Conyers pushes bill” 1999; Reference DumanovskyDumanovsky 2000; Reference Fagan and DaviesFagan & Davies 2000; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1999; Reference Holmes, Reynolds, Holmes and FaulknerHolmes et al. 1999; Office of the Attorney General of New York 1999; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 1999). Research suggests that a citizen's association with familial (Reference Clear and RoseClear & Rose 1999) and social network experiences (Reference DavisDavis 1990; Reference FeaginFeagin 1991) within the criminal justice system may influence assessments of police–citizen encounters as well. Citizens who report negative encounters with police are significantly more likely to judge police misconduct seriously than citizens who report no prior experience.

Research Design

This study employs the techniques of a factorial survey, a methodology that combines the concepts of sample surveys and experimental design. Building on the advantages of surveys, the factorial survey allows for a large random sample; building on the advantages of experimental design, the method may “accommodate to the complexity of issues involving norms” by incorporating the notion of independent treatments into the design and construction of vignettes (Reference Rossi and BerkRossi & Berk 1997:36). Even when a respondent does not have firsthand, real-life experience with a subject such as police misconduct, a factorial survey allows respondents to make judgments based on a “contrived but enriched set of choices” arrayed in each vignette or script (Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and NockRossi & Anderson 1982:28). Although most of the respondents to a study of police misconduct may not have directly experienced this form of behavior from an officer, they surely have been exposed to stories told by others and certainly to press and other media accounts of alleged misconduct. Everybody may know about police misconduct, just as everybody may know about adultery, even if they have not been adulterous. The goal of the factorial design, then, is to fill in the space created by the probable absence of real-life experience for most respondents.

As mentioned earlier, the vignette of a police–citizen encounter was constructed after an analysis of a random sample of closed and redacted cases that were filed with the CCRB in 2000 and two focus groups with in-take officers at the CCRB. CCRB cases were coded through an inductive process. In the first stage, cases were coded for (1) a description of the alleged stop, and (2) the various types of FADO that the alleged victim experienced, from offensive language through unnecessary force. Based on a reading of files, codes were then added to capture possible injury to the victim and to the police officer. In many instances, reports included information about follow-up interviews with various parties, including the victim, the officer, or eyewitnesses; based on this information, a dimension capturing information about a police officer's explanation was added to the coding process. In developing the vignette template, some dimensions were included that were eventually dropped (e.g., social status of police officer, mental health status of the victim). Dimensions were deleted based on findings during an extensive pilot study where experimentation with the length of the vignette showed that there is a limit to the number of dimensions that can reasonably be handled by a respondent in a telephone interview. Through this iterative process, in combination with results from a pilot study, a generic vignette of a police–citizen encounter composed of a series of fourteen fixed dimensions was developed. Thus, the vignette template reads:

A police officer [1. Mobilizing Event, including 2. Ethnicity, 3. Age, and 4. Gender of civilian]. The man/woman [5. Demeanor of Civilian 1 and 6. Demeanor of Civilian 2]. The police officer [7. Discourtesy/Offensive Language and [8. Abuse of Authority]. The Civilian 9. Demeanor of Civilian 3]. Later, the officer [10. Force]. The civilian [11. Demeanor of Civilian 4]. The officer [12. Police Authority].

As a result of the interaction, [13. Injury-civilian] and [14. Injury-officer].

Each dimension contains levels, or descriptions appropriate to the dimension; for example, the dimension of age might be captured by the level teen or middle-aged. The coded CCRB cases were particularly useful in generating a series of realistic, plausible levels. The number of levels within a dimension varied from, for example, twenty-one levels for the dimension for a mobilizing event to four for the dimension for age.Footnote 9

Each vignette contains, at minimum, information about Dimension 1, the mobilizing event; Dimension 4, gender; Dimension 5, the civilian's initial demeanor; and Dimension 7, discourtesy/offensive language by the officer. The organizing dimensions of this study are various forms of police misconduct: namely, unnecessary force (Dimension 10), abuse of authority (Dimension 8), discourtesy and use of offensive language (Dimension 7). Dimension 7, discourtesy/offensive language, is treated as a baseline of misconduct and is included in all vignettes. This decision was based on (1) a review of actual case filings with the CCRB that showed that the vast majority of cases filed include complaints that describe encounters that begin with offensive language and then escalate to abuse of authority or use of unnecessary force by an officer as well as (2) the regulations that guide police practices, where discourtesy and offensive language are less-serious forms of misconduct than abuse of authority or the unnecessary use of force.

Once the dimensions and levels were developed, rates of inclusion were calculated.Footnote 10 While all vignettes contain information about the mobilizing event, the citizen's gender and initial demeanor, and the officer's use of offensive language/discourtesy, other dimensions appear with varying degrees of frequency.

With the dimensions, levels, and rates of inclusion of dimensions and levels set, vignettes were then randomly generated as a sequence of events in the order reported in the generic vignette above, including random omission of information (i.e., blank dimension). Thus, the construction of the vignettes was designed to establish how the other situational dimensions (e.g., age, ethnicity, gender, the citizen's demeanor and reaction to the officer, or escalating misconduct such as force) affect respondents' judgments about the level of misconduct. Prior to data analysis, a correlation matrix of all levels was tested to confirm randomness, or no significant correlation among the levels.

Each respondent was administered a set of seventeen randomly constructed vignettes. At the conclusion of each vignette, respondents were asked to perform two tasks: (1) to rate the level of misconduct perceived in the encounter, where zero (0) is “no misconduct” and ten (10) is “serious misconduct,” and (2) to indicate the type of punishment the officer should receive for his or her behavior in the case, from a low of “no punishment” to a high of “prison for more than one year.” Respondents were also asked a short series of survey questions, focusing on political attitudes, prior experience with the police, and demographic indicators. During the pilot phase of the study, experiments with the organization of the survey were tested to ensure the most reliable results. Based on these findings, the organization of the instrument was as follows: (1) survey questions on political attitudes, (2) eight vignettes, (3) survey questions on prior experience with the police, (4) nine vignettes, and (5) demographic profile; this organization of the instrument reduced problems of respondent fatigue.

The survey was administered by telephone to a random sample of 1,100 respondents in New York City, 18 years and older. The survey was administered by Schulman, Ronca & Bucuvalas, Inc. of New York City, from June through August 2002, using Random Digit Dialing (RDD). The survey was administered in English only, and each interview lasted from twenty to twenty-five minutes.Footnote 11 The response rate ranged from 62.5 to 58.4%.Footnote 12

Thus, the final database consists of 18,443 vignettes.Footnote 13 Because each level within a dimension was randomly assigned and thus orthogonal or independent of the other levels, with a sufficiently large sample of vignettes this methodology allows for the assessment of the unique impact of each dimension/level on a respondent's evaluation of the scenario.

The factorial design allows for the analysis of findings where the unit of analysis is the respondent or the vignette. First, findings are reported where the vignette is the unit of analysis; the goal of this analysis is to develop a picture of which levels within the various dimensions are significant in an explanation of the rating for police misconduct. Specifically, we report on an analysis undertaken to determine how all of the levels for all of the dimensions in the vignette affect the ratings given by respondents. Because each vignette contains a dimension level that was randomly generated, the dimensions (and levels) are uncorrelated with one another. Thus, we can assess the unique impact of each dimension and level on the respondent ratings. Also, to account for intra-respondent correlation, we analyze vignette models using Huber-White heteroskedasticity-corrected standard errors.Footnote 14 Building on the analysis of vignettes, we examine the relative impact of each dimension on respondents' ratings of the seriousness of the police misconduct as well as respondents' mean seriousness rating as a way of controlling for a respondent's tendency to give low, intermediate, or high ratings. To test the relative impact of each dimension, we use coding proportional to effect models where the resultant squared betas (B2) “can be interpreted as an index of importance, and, if complete orthoganality were maintained, the sum of the each B2 would equal the overall R2 and each B2 could be interpreted as the proportion of variation in the Y, [the abuse ratings] explained by each dimension” (Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and NockRossi & Anderson 1982:49). Finally, we examine findings where the unit of analysis is the respondent to test the relative impact of structural, attitudinal, and experiential models on the rating scores.

Findings

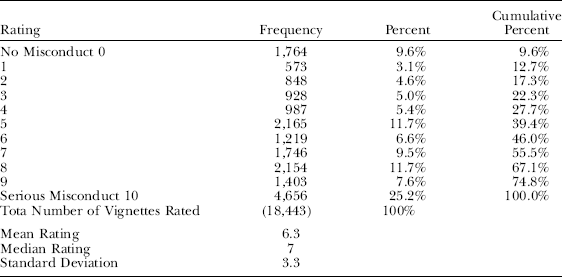

Table 2 reports the distribution of ratings of misconduct by respondents, where 0 means “no misconduct” and 10 means “serious misconduct.” Respondents perceived no misconduct in 10% of the cases. In all, about 20% of the vignettes were given a rating of 3 or less, indicating that they were not deemed as containing very serious misconduct. At the other extreme, 25% of the vignettes were given the highest rating of 10. The mean score was 6.3, and about half of the ratings were at least 7 or higher.

Table 2. Distribution of Rating of Seriousness of Misconduct

Table 3 reports additional, descriptive findings and shows the average rating of vignettes where they contain (1) only the presence of offensive language or discourtesy (mean=5.2), (2) offensive language/discourtesy and abuse of authority (mean=5.9), (3) discourtesy/offensive language and force (mean=7.2), and (4) offensive language/discourtesy, abuse of authority, and force (mean=7.3). The findings reported in Table 3 suggest that, on average, citizens concurred with the regulatory scheme and tended to rate vignettes that contain only offensive language/discourtesy as less serious than those that contain some combination of abuse or unnecessary force along with offensive language/discourtesy. Thus, the increment of abuse of authority elevated citizens' average ratings to 5.9. The addition of unnecessary force to offensive language/discourtesy (row 3) yet again elevated respondents' average rating to 7.2. On the other hand, the addition of abuse to the presence of discourtesy/offensive language and unnecessary force appeared to make a very minor difference in the eyes of the public (an average of 7.3). At first glance, the relatively large standard deviations for each level of misconduct suggest some disagreement across the public concerning these ratings; however, as we show later, the variation in the scores across respondents is due in large measure to differences among respondents regarding their propensity to give high, low, or moderate seriousness scores.

Table 3. Respondent Rating of Seriousness of Police Officer's Misconduct by Type of Misconduct

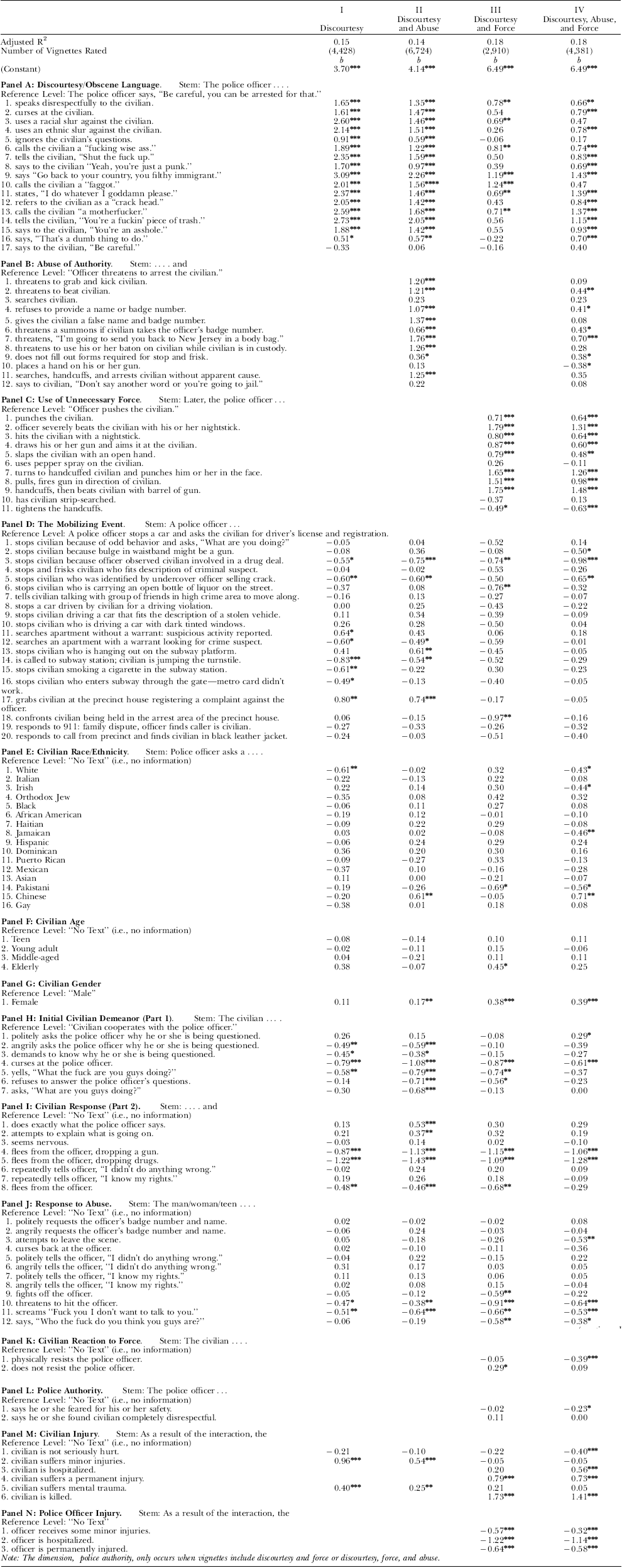

To explore this and related questions, Table 4 reports findings of a set of regression equations where seriousness of misconduct ratings were regressed on vignette dimensions separately for four combinations: (I) discourtesy/offensive language, (II) discourtesy/offensive language and abuse of authority, (III) discourtesy/offensive language and unnecessary force, and (IV) discourtesy/offensive language, abuse of authority, and unnecessary force. Reported in Table 4 are the unstandardized regression coefficients (b) attached to the levels for each dimension of an encounter on respondent ratings. Panels A to C of Table 4 show the nonstandardized coefficients for the dimensions of FADO; Panels D to N show the nonstandardized coefficients for the surrounding circumstantial or extralegal dimensions.

Table 4. Regression of Seriousness Ratings on Vignette Characteristics Using Robust Standard Errors: Separately for Vignettes Describing Four Types of Misconduct

1 Dependent Variable: Rating–Rate the officer's behavior on a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 is no misconduct and 10 is serious misconduct.

* Sig.≤0.10; **Sig.≤0.05; ***Sig.≤0.01.

The Dimensions of FADO

If behavior is observed through a legalistic or professional lens, respondents will consider (1) misconduct as incrementally more serious, moving from offensive language to abuse of authority to unnecessary force, and (2) levels of misconduct to be relatively more salient than mitigating or extralegal dimensions.

The findings reported in Panels A to C of Table 4 suggest, however, that the public does not take the same incremental view of various forms of police misconduct as legal guidelines suggest. Column I in Panel A of Table 4 reports unstandardized regression coefficients and their level of significance for discourtesy/offensive language, net of other dimensions within the respective columns (Panels D to N). That is, Column I shows findings for vignettes that only include discourtesy/offensive language. The reference category for the dummy variables for this dimension stated, “The police officer says, ‘Be careful, you can be arrested for that.’” This level was selected as a point of reference because it is a fairly benign statement of advice; not unlike the ways in which the phrase “be careful” might be interpreted, which, these findings show, are not significant. In other words, the findings suggest that should an officer's behavior imply advice to a civilian to comply with legitimate expectations, as predicted, no misconduct is construed to take place.

But the picture is quite different when language moves to being either implicitly or explicitly offensive. Being told that an officer “cursed at the civilian” elevated ratings by more than one point (b = 1.61), whereas being told that an officer told the civilian, “Go back to your country, you filthy immigrant” elevated respondents' scores by just over three points (b = 3.09). Thus, regardless of the motivating event that triggered the encounter, including some events where the citizen engaged in observable illegal activity; the race, age, or gender of the victim; or civilian demeanor toward the officer, including initially hostile behavior toward the officer, a police officer's discourtesy or offensive language remained highly salient in an explanation of respondents' evaluation of the seriousness of misconduct.

As shown in Column II of Table 4, the public's strong antipathy toward officers' use of offensive language and discourtesy remained significant when abuse of authority was added to the equation (See Panels A and B of Table 4). Abuse is considered in two ways: threatening behavior and disregarding police rules such as giving one's name and badge number when asked. The reference level for abuse stated, “The officer threatens to arrest the civilian.” Column II of Panel B shows that, in comparison to the threat of arrest, other types of threats or levels of abuse did remain salient (i.e., significant). However, a comparison of the relative effects (i.e., levels) of the dimensions for discourtesy/offensive language and abuse of authority shows that explicit language tended to drive the evaluation of misconduct. This is particularly clear for the levels of discourtesy/offensive language where the officer said, “Go back to your own country, you filthy immigrant” (b = 2.26) or “You're a fuckin' piece of trash” (b = 2.05); each of these levels had a significantly greater impact on perceived seriousness than any of the levels reported for abuse of authority. To explore this finding, an alternative model was tested where only very mild forms of discourtesy were included in the regression (table not shown); these findings show that the coefficients for abuse remained significant but relatively weaker than those for levels of discourtesy/offensive language.Footnote 15 These findings begin to document the degree to which the public finds offensive language/discourtesy problematic in and of itself as well as in the face of more serious forms of misconduct.

When the use of unnecessary force occurred in combination with discourtesy/offensive language, the more explicit levels of discourtesy/offensive language remained significant (Column III, Panel A of Table 4). For example, an officer calling a citizen a “filthy immigrant” (b = 1.19) or a “faggot” (b = 1.56)—even in the presence of the use of unnecessary force—remained significant and elevated respondents' ratings. On balance, these findings show that, as expected if observed through a lens of professionalism, unnecessary force in the presence of offensive language has a greater relative impact on respondents' ratings; on the other hand, offensive language does not altogether drop out of respondents' judgments.

What happens, then, when an encounter involves all forms of misconduct considered in this study (see Column IV of Table 4)? Interestingly, most levels of discourtesy/offensive language (see Panel A, Column III) remained significant again, underscoring that citizens expect officers to behave, whatever the circumstance. When abuse of authority took place in combination with force and discourtesy/offensive language (Column IV, Panel B of Table 4), most levels of abuse dropped out and were not significant in explaining respondents' estimations of misconduct; indeed, one level—an officer placing a hand on a gun (b = −0.38) appeared to reduce the evaluation of the seriousness of misconduct. These findings again suggest that the combination of language and force has the greatest impact on judgments of misconduct. Moreover, these findings remained when the model only included more benign levels of discourtesy/offensive language (not shown in tabular form; see footnote 15 infra). That is, in all instances, the public judged levels of abuse as significant but relatively less powerful forms of misconduct than discourtesy/offensive language and force.

Do the findings support the claim that citizens expect officers to behave legalistically, to behave by the book? First, as expected, respondents did not observe misconduct when officers gave advice, a baseline level of the dimension for discourtesy/offensive language. Second, as predicted, in vignettes that only displayed discourtesy/offensive language, respondents observed explicitly and implicitly offensive language as significant, net of circumstantial or extralegal dimensions. Third, when abuse of authority was added to the story, contra predictions, respondents did not observe threatening or rule-breaking behavior as incrementally more serious than discourtesy/offensive language. Fourth, as predicted, the unnecessary use of force in a vignette did trump discourtesy/offensive language and abuse of authority, but with the caveat that offensive language, especially explicitly offensive language, still looms in respondents' judgments.

Together, the findings begin to support the notion that citizens expect officers to follow the rules, though findings for levels of abuse of authority complicate this picture. Indeed, the findings suggest that the public appears to accept some role for an officer's discretionary use of threatening authority. That is, the findings suggest that in the midst of a volatile encounter, such threatening behavior may be construed by the public as an officer's legitimate use of street-level, discretionary authority to gain control over the situation.

How do the circumstantial, or extralegal, dimensions of a police-citizen encounter affect judgments? That is, how does the mobilizing event, social status, or a citizen's demeanor matter? Panels D to N of Table 4 report these findings.

Mobilizing Event

In this section, we look at the relative influence of the mobilizing event (Panel E), or the nature of the stop that gives rise to the police–citizen interaction. Often, when an officer initiates an encounter, he or she is making a judgment call about what appears to be suspicious behavior. For example, someone may appear to be engaged in odd behavior, suggesting that the officer should investigate, or ask what is going on; or a citizen may fit the description of a criminal suspect and the officer may decide to stop the person. In these types of instances, the mobilizing event is fraught with ambiguity, though the better part of discretionary responsibility to the public to ensure order may suggest that the officer should act on the hunch. Less ambiguous, a mobilizing event may require proactive policing, such as when a person may be engaged in overtly illegal behavior; for example, jumping a turnstile in the subway or smoking on a subway platform, and the officer's role to gain control over the situation is clearer.

In interpreting the findings for the relative impact of the mobilizing event on respondents' judgments, the level of reference stated, “A police officer stops a car and asks a civilian for a driver's license and registration.” The reference is ambiguous—that is, it may be implied that there was a violation, but it is not altogether clear. The findings reported in Panel E of Table 4 show that, on balance, the levels that gave rise to the encounter were not significant (Columns I–V), though there was a slight tendency for illegal behavior that required proactive policing, such as observing a drug deal or jumping a turnstile, to significantly reduce respondents' evaluation of the seriousness of misconduct. When a civilian is grabbed in a precinct house while registering a complaint did significantly increase the seriousness of perceived misconduct. What is perhaps more striking is the degree to which the mobilizing event did not matter. In the vast majority of circumstances, the ambiguity of a situation that may have required police action or even involved more clearly illegal activity by a citizen did not trump the reaction to actual discourteous, offensive, or forceful behavior by an officer.

Overall, the findings show that, contrary to expectations, citizens do not alter their judgments of FADO when officers react to a citizen's call for help; a similar pattern held when the initiating event was ambiguous, i.e., there may or may not have been illegal behavior by the civilian. That is, neither reactive nor ambiguous mobilizing events were significant. On the other hand, as predicted, when officers were depicted in proactive initiating events, or responding to illegal civilian behavior, respondents were significantly more likely to reduce ratings of misconduct. Under some limited circumstances, then, the findings for the dimension, mobilizing event, do suggest that citizens are willing to grant officers a degree of latitude, as evidenced by the significant reduction in scores associated with the demands of proactive policing.

Social Status

A citizen's, age, race, and gender—or social status (shown in Panels E, F, and G, respectively)—provide cues to the officer, and the observer-respondent, about the person that the officer must interact with. For the purposes of this study, social status was operationalized as race/ethnicity, age, and gender. Prior research (Reference Rossi and BerkRossi & Berk 1997) has not found a significant race effect in related arenas of research. Because minorities are significantly more likely to be stopped by the police (Reference Langan, Greenfield, Smith, Durose and LevinLangan et al. 2001; Office of the Attorney General of New York 1999), to report negative experience with the police (Reference Langan, Greenfield, Smith, Durose and LevinLangan et al. 2001; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2000; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 1999), and to be incarcerated (Reference Pastore and MaguirePastore & Maguire 2001), this normative dimension of the public's view is particularly salient. As the findings reported in Panel E of Table 4 show, race/ethnicity was operationalized by a wide range of terms; this step was taken in order to develop more subtle levels of this dimension.Footnote 16 In addition,the reference level is “no information” about race; we wanted to know if, in comparison to “no information” about the race of the civilian, an ethnic or racial identifier makes a significant difference in the degree of seriousness of misconduct. Overall the findings reported in Panel E of Table 4 (Columns I–V) show that knowing the race of the victim does not appear to matter: it neither increased nor decreased the score.Footnote 17 The findings reported for age (see Panel F of Table 4, Columns I–V) show a similar effect. Whether a respondent was given information about a civilian's age neither positively or negatively impacted the score for misconduct.

But the findings reported for information about gender tell a slightly different story. Here, the findings reported in Panel G of Table 4 (Columns I–V) suggest a degree of gender stereotyping in judging police misconduct. Thus, in instances of police use of discourtesy/offensive language in combination with abuse (Column II), force (Column III), or abuse and force (Column IV), respondents were significantly more likely to increase their rating of police misconduct when the behavior was directed at a female, particularly when force was involved.

The findings reported here regarding the impact of the dimensions of social status do not corroborate most expected predictions. First, age did not affect judgments of the seriousness of misconduct. Second, the findings support a theme in criminological research that demonstrates a tendency to stereotype gender; in the case of police misconduct, stereotyping occurred to the extent that respondents were more likely to give higher scores for police misconduct when the police behavior was directed at a woman, regardless of that woman's civilian demeanor.

Civilian Demeanor

Prior research suggests that civilian demeanor is salient in a number of ways. In a study of the normative dimensions of sentencing guidelines, Reference Rossi and BerkRossi and Berk (1997) find that, all other things being equal, the public tends to perceive the appropriateness of a harsher sentence for civil rights violations by police officers when the victim's demeanor is polite or cooperative. Observational studies of police practices demonstrate that civilian demeanor, and particularly a polite demeanor, is the single most important and consistent factor in shaping actual encounters (Reference KlingerKlinger 1994, Reference Klinger1996, Reference Klinger1997; Reference Mastrofski, Reisig and McCluskeyMastrofski, Reisig, & McCluskey 2002; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2000).Footnote 18 Panels H, I, J, and K of Table 4 report findings on civilian demeanor at various stages in the encounter, from the citizen's initial reaction to a stop by an officer (Panels H and I) through a citizen's possible response to the unnecessary use of force (Panel K). (In interpreting these findings, it is important to keep in mind that all vignettes contained, at a minimum, the civilian's initial response to the police officer—see Panel H; after this baseline, some vignettes provided additional information about citizen demeanor.)

Panels H and I of Table 4 report the respondents' initial impression of the civilian's behavior where the level of reference is that the civilian was polite, or “cooperates with the police officer.” In encounters where only discourtesy/offensive language was involved (Column I, Panel H and I of Table 4), a citizen's polite behavior (e.g., cooperative, does what he or she is told) did not matter. On the other hand, hostile language, confrontational behavior (e.g., cursing, yelling “What the fuck are you guys doing?”), or illegal behavior (e.g., fleeing, dropping a gun or drugs) by the civilian did significantly reduce citizens' evaluation of discourtesy or use of offensive language. Put differently, the public does not give points for politeness by a civilian, but it does significantly change its view of possibly abusive tactics by an officer when the citizen is confrontational.

As interactions became more complex, where abuse of authority and unnecessary force were added to the equation and where there were additional opportunities for the civilian to demonstrate a demeanor (Panels J and K), a theme in support of police discretion is shown (see Panel I, levels 1 to 8, Columns II, III, and IV). That is, as the circumstances of an encounter escalated and a citizen's behavior became more verbally (e.g., “What the fuck are you guys doing?”) or behaviorally confrontational, if not illegal (e.g., fleeing from the officer, dropping a gun or drugs), the public was significantly less likely to observe police misconduct.

Here, then, as predicted, civilian demeanor does matter: An evaluation of serious misconduct is significantly less likely to be observed when a civilian's demeanor is confrontational or possibly illegal. But a polite civilian demeanor does not significantly increase judgments of police misconduct. Together, the findings suggest that as a civilian's demeanor becomes more aggressive, in keeping with a model of street-level discretion, respondents defer to an officer's authority to assert control over the situation or to prevent possible further escalation of the situation.

Police Authority

After the dust settles, an officer may have an explanation for his or her need to take control of the situation or to clarify why he or she used authority in a particular manner (Columns II and III, Panel L of Table 4). Interestingly, however, a police officer's explanation of his or her actions does not carry weight with the public.Footnote 19 Respondents do not judge significantly the levels of the dimension, police authority, as predicted.

In many respects, this dimension is a powerful test of the street-level discretionary lens, because an officer is given the opportunity to explain his or her behavior. While others report that findings show that trust in the police is essential for their legitimacy and the acceptance of their actions (Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002:58–75), the findings reported here suggest an absence of public trust in the explanation of an officer for his or her behavior in the context of an often contentious exchange with a victim. The word of an officer, or the rationale for his or her behavior, does not trump his or her observed actions and lends support to the claim that explanations of self-protection are of limited value in ensuring the legitimacy of the role of police in society (Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002:199).

Injury

Finally, an encounter may end in injury or even death (Columns III and IV, Panels M and N of Table 4). Does this have an impact on public evaluations of the seriousness of police misconduct? The findings reported in Table 4 show that injury does make a significant difference: If a person was hurt as a result of an interaction, respondents were significantly more likely to give a higher score for misconduct. Interestingly, if a citizen suffered mental trauma as a result of a verbally offensive or discourteous officer (Column I, Panel M of Table 4), the public was significantly more likely to judge serious misconduct, once again underscoring the public's low regard for such forms of unprofessional behavior. On the other hand, if an encounter escalated and an officer was injured in the line of duty, the public was significantly less likely to perceive the circumstances as involving misconduct. As predicted, levels of injury to the civilian significantly increased judgments of serious misconduct, while levels of injury to the officer significantly reduced judgments of serious misconduct.

Overall, the findings reported in Table 4 show that some select mitigating or extralegal circumstances do matter in respondents' judgment of police misconduct, particularly a confrontational or illegal civilian demeanor. But other mitigating circumstances, including the motivating event, race/ethnicity, or police authority, do not outweigh the centrality of the dimensions of FADO, specifically discourtesy/offensive language and unnecessary force. Having said this, the findings for levels of abuse of authority, like those of civilian demeanor, do, however, suggest a normative balancing that allows for a degree of street-level discretion on the part of the officer.

The results of the regression equations presented in Table 4 show that the dimensions/levels contained in the vignettes explain anywhere from 15 to 19% of the variation in the abuse rating variable, depending, of course, on the combination of force, abuse, discourtesy and offensive language dimensions contained in the vignettes.

Which dimensions are most important for respondents' judgments?

To assess the relative impact of each dimension on respondents' judgments, variables were constructed using the technique of “coding proportional to effect,” where the values of each level within a dimension were recoded to the corresponding regression coefficient reported in Table 4. Coding the dimensions/levels proportional to effect made it possible to create a quantitative dimension to be used in a regression equation to assess and compare the dimensions according to their overall contribution to the judgments regarding abuse.

Table 5 shows the results of regressing the misconduct rating on the thirteen coded proportional-to-effect dimensions (effect-coded dimensions).Footnote 20 Note that the resulting R2 will be the same as that obtained using the dummy variables reported in Table 4. The unstandardized regression coefficients (b) in Table 5 are all equal to or close to one but are not, however, interpretable (Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and NockRossi & Anderson 1982). But the standardized coefficients reported in Table 5 show the relative contribution of each dimension to an explanation of police misconduct, without (Column I) and with the respondent's mean rating (Column II) in the model. As noted earlier, because the dimensions/levels are independent of one another, the sum of the squared betas equal the overall R2 and betas squared are equal to the proportion of the variation in Y accounted for by each dimension (Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and NockRossi & Anderson 1982). The findings reported in Table 5 summarize and distill those detailed in Table 4. Turning to the findings reported in Column I, in order of relative importance, the four most salient dimensions in an explanation of police misconduct were (1) force (B = 0.23), (2) discourtesy (B = 0.17), (3) demeanor (B = 0.15), and (4) abuse (B = 0.12); a civilian's social status, the issues that gave rise to the stop, or the civilian's demeanor were noticeably less important. These findings again underscore the greater weight given to discourtesy/offensive language and force relative to levels of abuse of authority in judging police misconduct.

Table 5. Regression of Seriousness Ratings on Effect Coded Dimensions

* Sig.≤0.10;

** Sig.≤0.05;

*** Sig.≤0.01.

Column II of Table 5 adds respondents' mean rating (average of all respondent ratings) as measured by the difference between the actual rating given by respondents to the vignette and a predicted rating for each vignette a respondent rated (see footnote 20). The findings show that a respondent's tendency to rate vignettes above, below, or equal to the predicted rating accounted for most of the variance in the vignette ratings. Note that the R2 goes from 19 to 48%. That is, judgments were affected by each respondent's tendency to give low, high, or intermediate ratings.

Are respondents' ratings explained by social status, political attitude, or prior experience with the police?

What accounts for a respondent's tendency to rate vignettes high or low? To examine this question, we change the unit of analysis from the vignette to the respondent. The dependent variable in Table 6 is the aggregated “Seriousness Rating – Predicted Rating” score for each of the seventeen vignettes rated by each respondent. In the balance between social status, attitudinal, and experiential factors, the findings reported in Table 6 show that respondents' income, gender, and race drove differences in the judgments of the seriousness of police misconduct. That is, all other things being equal, blacks were significantly more likely to give higher seriousness ratings than whites; women were significantly more likely to observe police misconduct than men; and those who reported household income of $75,000 or less were significantly more likely to observe serious misconduct than people with higher incomes. It is noteworthy that, while the race of the civilian in a vignette was not significant in predicting more serious scores for misconduct (see Tables 4A and 4B), the findings reported in Table 6 make clear that the respondent's race/ethnicity remains a significant driver in differential levels of judgment.

Table 6. Regression of Mean Seriousness1 Rating on Characteristics

1 Dependent Variable: Mean of Respondent Rating minus Predicted Rating for the Vignette

* Sig.≤0.10;

** Sig.≤0.05;

*** Sig.≤0.01.

Political attitudes are also significant. Those who reported that they observe that the police are disrespectful when dealing with people in their neighborhood were significantly more likely to judge misconduct as more serious than those who observe more respectful treatment by police in their neighborhoods. A similarly significant pattern of difference was apparent in those who believe that the police do not do a good job of policing those who misbehave and that it is inappropriate for officers to use force against people suspected to be troublemakers. Taken together, the findings reported in Table 6 suggest that those with a lower tolerance for police discretion are, in turn, more likely to judge misconduct as constituting more serious misbehavior.

Meanwhile, prior negative experiences with the police, either directed at the respondent or a respondent's friends or family, were not a significant factor in explaining differing levels of police misconduct (but see Reference Clear and RoseClear & Rose 1999). When these models were tested separately for blacks, whites, and Latinos, the findings held (not shown in tabular form). Together, the findings reported here do not support the hypothesis that prior negative experiences with the police, either directly or indirectly through family members and friends, explain respondents' evaluations of misconduct.

Discussion

The research reported here has analytical implications for understanding the public's judgments about police misconduct as well as policy implications for how the police may improve relations with the public that are derived from empirically grounded and systematic research. On the analytic front, this research goes beyond more traditional survey findings by specifying the normative dimensions of an interaction that shape public understandings; briefly, the public judges the role of police as ensuring order through a lens that gives weight to a respect for professional guidelines. On the policy front, this research concretely and dramatically demonstrates the degree to which language can be a powerful barrier to effective police–community relations. In this discussion, we begin with an analytical consideration of the implications of this work and then turn to a consideration of how policy makers might incorporate these findings into training for improving police–community relations.

On one level, the findings reported here complement those from other surveys that ask respondents to rate their support for various tactics that include force in more abstract terms. The findings show that the public takes a dim view of what it deems to be the unnecessary use of force by the police. General surveys have not, however, asked respondents about officers' use of offensive language. Based on the findings reported here, offensive language, or what might be called very“bad manners” (Reference Sherman, Gottfredson, MacKenzie, Eck, Reuter and BushwaySherman et al. 1997:8-1, as quoted in Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002:203), may be added to the list of the forms of police misconduct that offend the public. To the extent that these two dimensions drive judgments of police–civilian interactions, the findings suggest that respondents rate misconduct with the expectation that officers are to be held accountable to standards of professionalism. Put differently, and succinctly, while vulgar language such as calling someone a “fucking wise ass,” as we heard in the introduction to this article, may be a part of everyday speech, it carries a very different meaning when voiced by police officers.

The findings do show, however, that respondents demonstrate some appreciation for the role of street-level discretion, gleaned from observational studies of policing. Two patterns from the empirical findings suggest recognition of the role of police discretion, including the use of “dirty means.” First, levels of abuse of authority or threatening behavior—such as an officer's move to place a hand on a gun, as we heard at the beginning of this article—do not affect respondents' judgments of serious misconduct; the empirical pattern for this dimension suggests that abusive, or threatening, behavior may be construed by the public as part of an officer's legitimate social control, or deterrent, toolkit. Second, civilian demeanor, specifically confrontational behavior, significantly reduces a judgment of serious misconduct. Respondents judge misconduct with some expectation that an officer's role does include the need to ensure compliance with authority—at least when the deterrence is not directed at the respondent him- or herself (i.e., see Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002, who show greater motivation by respondents to comply with legal authority when emphasis is given to proceduralism over deterrence).