In common law judicial systems, the lawyers representing the litigants play a significant role in the judicial process. Typically, they are responsible for the presentation of information to the courts. Moreover, given the adversarial nature of the system, as well as the courts' need for information to formulate decisions, the relative abilities of the litigators can influence case outcomes. Indeed, studies of the U.S. judiciary have found empirical support for this theory (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995; Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999; Reference JohnsonJohnson et al. 2006; Reference KritzerKritzer 1998). To adequately develop and test the hypothesis that the relative abilities of legal counsel affect judicial decisionmaking, this theory should be investigated in other common-law contexts beyond the U.S. judicial system. As such, we examine the impact of lawyer capability on the decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). While Canada (and its judicial system) is similar to the United States (and its judicial system) in many respects, there are still significant differences between the two states. For example, until recently Canada did not have the functional equivalent of a Bill of Rights (The Charter of Rights and Freedoms is barely 20 years old). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that lawyers do not have an effect on SCC agenda-setting (Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming & Krutz 2002b). Given the differences between Canada and the United States, if the attorney capability theory extends to the merits decisions by the SCC, it only bolsters the importance, and in particular, the generalizability of the theory.

Lawyer Capability

Prior studies have posited several aspects of the concepts we combine under the rubric lawyer capability.Footnote 1 One element of lawyer capability is prior litigation experience. Akin to one of the advantages of repeat player litigants, Reference McGuireMcGuire (1995, Reference McGuire1998) posits that experienced attorneys are more successful on average because the judges are more likely to trust and rely on the information presented by the attorney in the form of written and oral legal arguments. Since the repeat player attorney is more likely to argue before the court in the future, the judges know that the attorney is more likely to present accurate information for fear of future recriminations. Others argue that quality of representation extends beyond trust (Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999). Lawyers have several opportunities to persuade judges through the arguments they present to the court. In the context of appellate litigation, lawyers typically have the opportunity to submit written and oral arguments. Written arguments, called briefs in the United States and factums in Canada, contain statements of facts, a summary of the relevant legal issues, and an argument supported by relevant sources of law. Unlike their written counterparts, oral arguments provide the lawyer with a face-to-face opportunity to answer the judges' questions. As Reference JohnsonJohnson (2001) illustrates in the context of oral arguments, these are opportunities to provide the court with information that can, at a minimum, affect how the judges formulate their substantive policy choices. Indeed, Justices William Reference RehnquistRehnquist (2002) and Sandra Day O'Connor (Reference MauroMauro 2000) both indicate that the information provided by lawyers in either the brief or the oral argument may affect their decisions.

While the briefs and oral arguments are the tools utilized by the lawyers to persuade appellate judges, some lawyers are more adept at using these tools. Kritzer, in his study of lawyer/nonlawyer advocacy (1998), develops a typology that distinguishes between two types of expertise of appellate litigators: process and substantive. Substantive expertise is essentially a specialization in a particular area of the law. Both Justices Reference RehnquistRehnquist (2002) and O'Connor (Reference MauroMauro 2000) argue that substantive expertise may influence the U.S. Supreme Court justices' decisions, particularly in areas of the law in which the justices are relatively uninformed. Substantive experts, utilizing their superior understanding of the relevant legal principles, are presumably more skilled at constructing legal arguments within areas of their expertise.

Alternatively, process expertise is the familiarity with the institutional rules and characteristics of a particular court in which the lawyer litigates. Lawyers usually develop process expertise through either prior litigation experience or clerkships with that court. This type of expertise holds several theoretical advantages, including the previously described trust relationship posited by Reference McGuireMcGuire (1995, Reference McGuire1998). Moreover, the process expert presumably has a deeper understanding of the types of arguments that will persuade the judges, as well as the style for presenting these arguments. As Laurence Tribe, noted Harvard Law School professor and himself a frequent litigator before the U.S. Supreme Court, points out, knowing the justices themselves matters. Using this information, Tribe tries to construct the argument most likely to persuade at least five justices (Reference FranceFrance 1998). In addition, justices and experienced U.S. Supreme Court litigators alike both recognize that process expertise includes the recognition that policy arguments are often more persuasive than legal arguments (Reference MauroMauro 2000; Reference RehnquistRehnquist 2002). Furthermore, as Justice Reference RehnquistRehnquist (2002) illustrates in his typology of oral argumentation skills, style may also matter. Presumably, process expertise includes the development of the right type of style. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court justices seem to favor litigators who thoughtfully respond to the justices' questions in a slow, organized fashion (Reference RehnquistRehnquist 2002).

Several studies of decisions by U.S. courts have examined what we call lawyer capability (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998, Reference McGuire2000; Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999; Reference JohnsonJohnson et al. 2006; Reference Partridge and BermantPartridge & Bermant 1978; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998; Reference WheelerWheeler et al. 1987; Reference KritzerKritzer 1990, Reference Kritzer1998). Most of the studies measure expertise using prior litigation experience (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998), though others have examined prior clerkships (Reference McGuireMcGuire 2000) and substantive expertise (Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999). In general, the findings typically offer either strong (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998) or, at worst, qualified support of the lawyer capability theory (e.g., Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999; Reference McGuireMcGuire 2000). Moreover, there is reason to believe, at least at the U.S. Supreme Court, that the influence of attorney expertise is conditional on issue salience (Reference McAtee and McGuireMcAtee & McGuire 2007).

Most recently, Reference JohnsonJohnson et alia (2006) have significantly augmented our understanding of the nature of the relationship between lawyer capability and judicial decisionmaking. First, they find that Justice Harry Blackmun's grades of the oral arguments presented before the U.S. Supreme Court are positively related to several different measures of lawyer capability, including the quality of the attorney's law school alma mater; geographic proximity to Washington, D.C.; prior U.S. Supreme Court clerkships; federal employment positions (other than assistants to the solicitor general); and prior litigation experience. In other words, the quality of the presentation of the information by the attorney during oral arguments (as perceived by a Supreme Court justice) is a function of many facets of attorney expertise. Moreover, they also find that the Blackmun oral argument grades themselves are a significant predictor of the justices' votes. From this, one can conclude that more-capable attorneys are more likely to present quality oral arguments, and that better arguments are more persuasive. This is the first direct evidence of a causal link between lawyer capability and judicial decisionmaking.

Lawyer Capability and the SCC

Scholars have extended several theories of U.S. judicial decisionmaking to the SCC (e.g., Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming & Krutz 2002a, Reference Flemming and Krutz2002b; Reference McCormickMcCormick 1993; Reference OstbergOstberg et al. 2002; Reference Tate and SittiwongTate & Sittiwong 1989; Reference Wetstein and OstbergWetstein & Ostberg 1999). However, no one has directly studied the role of lawyerFootnote 2 capability in the Court's decisions on the merits. Two scholars, Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming and Krutz (2002b), do examine the impact of lawyer capability on decisions to grant leaves of appeal from 1993 to 1995. They find that prior litigation experience, as well as Queen's Counsel designation, does not increase the probability that the Court will decide to hear the case.

The null finding in the application of the lawyer capability hypothesis to agenda-setting by the SCC is consistent with the expressed perspective of some of the justices themselves. In his July 2002 interviews with several justices in Ottawa, Songer recalls three judge interviews in which lawyer capability was discussed. Judge B indicated that there is “little value” added from argument by the barristers because the case has been through so many judicial outlets that the issues are well defined by the time they reach the SCC. Judge F estimated that for about 75 percent of the cases the Court hears, it does not matter which side has the better lawyer in the case outcome, although good advocates may have an impact on how narrow the opinion is. Judge D echoed the sentiments of Judge F that the barrister's effectiveness may have an impact on how the opinion is written rather than on the outcome itself (Reference SongerSonger 2002).Footnote 3

While some SCC justices do not believe that lawyer capability affects case outcomes (and there was no observed effect on agenda-setting decisions [Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming & Krutz 2002b]), no one has systematically tested this proposition to validate the justices' positions on the issue. However, the empirical evidence that lawyer expertise (substantive and/or process) influences the behavior of U.S. appeals court judges (Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999) and U.S. Supreme Court justices (on the merits, Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998) cuts against the Canadian justices' contentions.

This argument is augmented by the institutional similarities between the U.S. Supreme Court and the SCC, as well as the roles of lawyers on both courts. For example, both courts consist of nine judges, including a chief justice and eight other associate (U.S.) or puisne (Canada) justices.Footnote 4 Similarly, after statutory changes in their jurisdiction, both courts now have substantial docket control. Akin to the U.S. Supreme Court's certiorari process, the SCC has the discretion to grant or dismiss the appellant's motion for leave to appeal in most cases.Footnote 5 Furthermore, lawyers for both sides submit legal arguments to the courts. Analogous to the briefs submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court, Canadian lawyers present factums to the SCC. The factums are similar to the briefs in that they contain a statement of the facts, as well as the questions in issue, and a legal argument (Supreme Court of Canada 2002). Finally, the SCC also holds oral arguments, providing the lawyers with opportunities to present their case in person (or by video conference) and answer the justices' questions. Of course, while lawyers in the United States have 30 minutes to argue their case, their Canadian counterparts each have one hour allotted for oral arguments.

Data and Methods

The data set included all appeals heard by the SCC from 1988 to 2000. All of the information came from the Canada Supreme Court Reports (CSCR; published by Canadian Government Publishing). The data represented the universe of all nonreference cases in the CSCR. These include criminal cases, civil rights and liberties claims, private economic disputes for which a clear upperdog exists, tort claims, disputes between the government and individuals, and disputes between national and provincial government entities. Reference cases, which are essentially advisory opinions by the Court, are authorized under Sections 53 and 54 of the Supreme Court Act (R.S., 1985, c. S-26). They enable the Court, upon the request of the executive or legislative branches, to interpret the dispute without a case or controversy. As such, they are generally not adversarial in nature and are therefore substantively distinct from the nonreference cases. Therefore, we excluded all reference cases from the model.

We incorporated in the model all nonreference cases from 1988 to 2000 in which an ideological direction could be determined. All in all, 256 of the 1,298 nonreference cases were excluded from the analysis because of missing data for one or more variables, including ideology, attorney experience, and party capability.

Since we were concerned with the influence of lawyer capability on judicial behavior, the dependent variable was the Court's decision for or against the appellant. The variable was dichotomous, coded 1 if the Court's decision supported the appellant and 0 if the Court voted in favor of the respondent. Since the dependent variable was dichotomous, we employed logistic regression to estimate the coefficients.

Main Independent Variables: Measures of Lawyer Capability

The main independent variables reflected three alternative characteristics of litigation teams that could influence the justices: Litigation Experience, Queen's Counsel (QC), and Litigation Team Size. Since the impact of a litigant's counsel is also a function of the relative quality of opposing counsel, the main independent variables were all operationalized as the difference between the value for the appellant and the value for the respondent. In other words, the prior litigation experience variables were first derived for the appellant's and respondent's counsel, and the actual variable incorporated into the model was the difference of the two values.

The first of the lawyer variables, Litigation Experience, has been incorporated into several prior studies of appellate court decisionmaking at both the plenary (Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming & Krutz 2002b; Reference McGuire and CaldeiraMcGuire & Caldeira 1993) and merits (e.g., Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999; Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998) stages. While most of these studies focus on prior litigation experience before the same court, there is no consensus regarding which lawyer experience matters. Some, such as Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming and Krutz (2002a), Reference HaireHaire et alia (1999), and Reference McGuireMcGuire (1995), utilize the most experienced litigator's value. Others, such as Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck (1997, Reference Wahlbeck1998), employ the experience value for the lead attorney (in the United States), while still others, such as Reference McGuireMcGuire (1998), rely upon the value for the orally arguing counsel. Given that there is no consensus, and each method has strengths and weaknesses,Footnote 6 we utilized two separate values: the most experienced lawyer and the average value for all of the members of the party's litigation team. (Unfortunately, we could not utilize the lead or orally arguing lawyers' experience, since that information is not listed in the CSCR and is not readily available to the public). Since the results did not significantly vary for either measure, and they were highly correlated, we present the latter value, which we contend is a more accurate reflection of the overall influence of the legal team. Moreover, we have reason to believe that each of the measures is highly correlated with the values for the orally arguing lawyer. In a similar analysis of U.S. Supreme Court litigation, one of the authors found that the orally arguing counsel's experience was correlated at the 0.80 (or higher) level with the experience values for the most experienced counsel, as well as the average for the entire litigation team (Reference SzmerSzmer 2005).

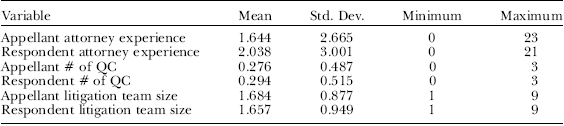

The actual value for each side's litigation experience was the natural log of the average number of casesFootnote 7 in the previous 10 termsFootnote 8 that each lawyer was noted in the published opinionsFootnote 9 as having participated before the SCC. In other words, for a lawyer participating in a case in 1988, the experience value was a sum of all prior participations from the 1978–1987 terms. We performed the logarithmic transformations of the raw experience value to consider the possibility of diminishing returns for additional experience for those litigators who had already participated in a substantial number of cases.Footnote 10 Before transforming the appellant and respondent experience averages, the values ranged from 0 to 21 for the respondent, and 0 to 23 for the appellant, with a mean of 2.038 for the respondent and 1.644 for the appellant (see Table 1). After transforming the variables, the maximum values were 3.18 and 3.09 for the respondent and appellant lawyers, while the means were 0.774 and 0.667, respectively. Finally, as previously noted, we believe it is the relative capability that matters, so the actual Litigation Experience variable was the difference between the logarithmically transformed average prior experience over the previous 10 terms for the appellant's and respondent's litigation team. Since the difference of the logarithms of the appellant and respondent values was equal to the logarithm of the ratio of the appellant to the respondent value (i.e., log(Appellant)−log(Respondent)=log(Appellant/Respondent), this could be roughlyFootnote 11 interpreted as the natural log of the lawyer litigation experience differential ratio.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of Litigation Team Characteristics

n=1042 (256 missing).

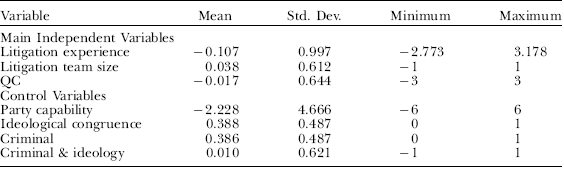

Table 2 provides the summary statistics for the Litigation Experience variable. The mean was −0.107 (the median is 0), with a range between −2.773 and 3.178. The standard deviation was almost 1. Fifty-nine cases were dropped from the analysis because the experience variable could not be calculated, either because no lawyers were listed for one of the sides or the names of one or the CSCR did not provide enough information to identify the one or more lawyers participating in the case.Footnote 12

Table 2. Summary Statistics for Sample Data of Supreme Court of Canada Appeals, 1988–2000

n=1042 (256 missing).

Given the results of prior studies, as well as the theoretical framework discussed above, we expected that the logistic regression coefficient for the Litigation Experience variable would be positive. In other words, we hypothesize that, all other things being equal, the Court is more likely to support an appellant represented by a more experienced litigation team than that of the opposing counsel.

The second lawyer capability variable, QC, measured the difference between the number of appellant and respondent litigators that have received this honorific designation from the provincial government. In the period between 1988 and 2000, between zero and three of the lawyers representing both the appellant and respondent were QCs (see Table 1). However, most parties were not represented by QCs, as indicated by the means less than 0.30 for the number of QCs for each side. The QC variable ranged from −3 to 3, with a mean slightly below 0 (see Table 2).

While the criteria for bestowing the title to lawyers in Britain typically include merit, this may not be the case in Canada. As Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming and Krutz (2002b) note, the criteria in Canada are more likely a function of experience and reputation (citing Reference Arthurs, Abel and LewisArthurs et al. 1988). Given that the Litigation Experience variable controlled for the experience aspect of the QC designation, we could assume that the coefficient for the QC variable reflects the “professional or public repute” element (Reference Arthurs, Abel and LewisArthurs et al. 1988, cited in Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming & Krutz 2002b). To the extent that reputation is a function of ability, the QC variable could be a proxy for the latter concept, which should, in turn, be positively correlated with the lawyer's ability to persuade the Court. As such, we anticipated finding a positive coefficient for the QC measure.

The third lawyer capability variable was Litigation Team Size, which measures the relative size of the teams of lawyers representing the appellant and respondent. The variable was coded 1 if the appellant had a larger litigation team, −1 if the respondent's team was larger, and 0 if they were represented by the same number of litigators.Footnote 13 As noted in Table 1, the litigation team sizes for both parties ranged between 1 and 9,Footnote 14 and the mean was approximately 1.7; the Litigation Team Size variable had a mean slightly above 0 (see Table 2).

While the previous measures focus on the quality of the lawyers participating in SCC litigation, no one has previously examined the quantity of the lawyers.Footnote 15 SCC litigators are often not solitary actors shouldering the entire work load. Indeed, most lawyers work with at least one co-counsel. Moreover, they have nonlawyer staffs providing research support. Presumably, these resources will enhance the persuasiveness of the arguments presented in briefs and oral arguments. Litigation team size lightens the load of the individual lawyers and increases the number of total person-hours spent researching, writing briefs, and preparing for oral arguments. For example, larger litigation teams have the opportunity to present practice oral arguments before a moot court of co-counsel. Moreover, we would expect that as litigation team size increases, the ability to anticipate all counterarguments increases. In other words, when more trained legal minds address a single topic, they are more likely to perceive all of the angles. Given the posited benefits of larger litigation teams, we anticipated finding a positive coefficient for the Litigation Team Size variable.

Control Variables

We also included several control variables in the model, including party capability, the ideological congruence between the median justice and the appellant's preferred position, whether it was a criminal case, and the interaction of the latter two variables. The Party Capability measure was constructed using the standard typology construct, assigning each party to a category based upon shared organizational characteristics that relate to resources and potential litigation experience. The categories were national government, provincial government, city/local government, business, organization or association, and natural person. While some of these categories are fairly general, this typology is consistent with the prior party capability research (Reference AtkinsAtkins 1991; Reference Brace and HallBrace & Hall 2001; Reference FaroleFarole 1999; Reference McCormickMcCormick 1993; Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995; Reference SheehanSheehan et al. 1992; Reference SmythSmyth 2000; Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1992; Reference SongerSonger et al. 1999; Reference WheelerWheeler et al. 1987). Furthermore, again consistent with prior work, we assumed a certain hierarchy of resources and litigation experience among the categories. This hierarchy follows the ordering of the categories listed above and is based on the assumption that the parties falling into the same category have similar resources and experience.Footnote 16 Both the method and the hierarchy are based on a long line of party capability research (see Reference SongerSonger et al. 1999). Of course, a recent meta-analysis by Reference Kritzer, Kritzer and SilbeyKritzer (2003) suggests that the variable really reflects the underlying supremacy of the “government gorilla,” which has added advantages beyond resources (e.g., control over the substantive and procedural rules governing the judicial process). Indeed, our replication of the Reference McCormickMcCormick (1993)“net advantage” calculations (the difference between a category's success rate as an appellant and loss rate as a respondent) supports this contention.Footnote 17 However, we incorporated the more precise measure in the initial model because of its prominence. In the latter models, it is apparent that the coefficients and standard errors for the main independent variables only changed slightly when we used alternative operationalizations reflecting the primacy of the government.Footnote 18

To construct the Party Capability variable, we assigned numbers for each side (appellant and respondent) based on the hierarchy: national governments were presumed to have the most resources and litigation experience, so they were assigned a 6, followed by provincial governments (5), local governments (4), businesses (3), associations (2), and natural persons (1). As noted above, the variable for party capability was actually the difference score (appellant party capability—respondent party capability). The values ranged between -5 and 5, with an average of −2.228, reflecting the likelihood that the government (scored higher) is more likely to respond to an appeal. Sixteen of the cases in the data set were dropped because the Party Capability variable could not be defined due to the inability to fit one or more of the litigants into the six-category typology.

Based on a myriad of prior studies (see Reference Kritzer and SilbeyKritzer & Silbey 2003), as well as the underlying theory first explicated by Reference GalanterGalanter (1974), we expected that the coefficient for the Party Capability variable would be positive. In other words, justices are more likely to vote in favor of appellants with more resources than their opponents, all other things being equal.

Based on prior research on other courts, as well as the SCC (Reference Wetstein and OstbergWetstein & Ostberg 1999), we assume that the attitudes of the justices are one potential factor that can influence their behavior. Indeed, given several institutional factors, we posit that the justices have the opportunity to incorporate their values into their decisions. Like their highly ideological colleagues on the U.S. Supreme Court, the Canadian justices serve during “good behavior,”Footnote 19 have substantial docket control, are not subject to review from a higher court, and are not bound by vertical stare decisis. Of course, as Reference Wetstein and OstbergWetstein and Ostberg (1999) and Reference McCormickMcCormick (2005) note, there are still differences between the two courts, including the selection process. According to Reference Wetstein and OstbergWetstein and Ostberg (1999), the absence of a contentious selection process in Canada leads to a less-divisive and potentially less-ideological court. Indeed, scholars have yet to amass the equivalent degree of evidence supporting the attitudinal model that one finds on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Absent a more refined measure, we employed an oft-used construct to estimate the preferences of the individual justices: the party of the appointing executive/Prime Minister (PM) (Reference Tate and SittiwongTate & Sittiwong 1989). In Canada, the judicial appointment power rests solely with the Prime Minister; unlike the U.S. Senate, the Canadian Parliament does not play a role in the process. Since the unit of analysis is the Court's decision in a case, we used a summary measure: whether a majority of the justices on the panel were appointed by a liberal PM. Moreover, given the nature of the dependent variable, the Court's decision for or against the appellant, we utilized an ideological congruence variable. If the Court's estimated ideology (either liberal or conservative) was congruent with the assumed ideological direction of the appellant's preferred outcome,Footnote 20 the variable was coded 1. If the Court's preferences were not congruent with those of the appellant, the variable was coded 0. For example, if the majority of the justices were appointed by a liberal PM, and the appellant preferred a liberal outcome (e.g., he or she was a criminal defendant), the variable was coded as a 1.Footnote 21 Given the nature of the variable and the attitudinal hypothesis, we expected that the coefficient of the Ideological Congruence variable would be positive.

Ideally, we would also include a variable distinguishing the method by which the Court took jurisdiction over the case—appeal as of right or leave petition. Presumably, in appeal as of right cases, where the Court does not have discretion over whether to hear the case, the substance of the appeal is more likely to be frivolous. As such, in those cases, the Court is presumably less likely to decide in favor of the appellant. Unfortunately, that information is not apparent from the published opinion. Therefore, we incorporated a proxy measure: whether the case involved a criminal issue. Since appeal as of right cases were limited to a subset of criminal cases during the 13 years (1988–2000) examined in this analysis, this variable should reflect this substantive distinction. The Criminal variable was coded 0 for criminal cases and 1 for those involving noncriminal issues. Given the theory, we expected to find a positive coefficient, indicating increased support for the appellant in noncriminal cases.

The final control took into account the possible interaction between ideology and the type of case. Presumably, in more routine cases, the justices will have less discretion over the outcome. As Reference DworkinDworkin (1985, Reference Dworkin1986) contends, the degree to which judges are constrained by the law depends on the difficulty, or complexity, of the case. In the so-called hard cases, judges have more discretion because the application of the relevant legal sources does not clearly lead to a single determinative outcome. Left less constrained by the bonds of the law, the justices are more likely to vote in accordance with their policy preferences. As such, the Criminal & Ideology variable reflects this interaction. The variable was coded 0 for all criminal cases, −1 for noncriminal cases if the Court's preferences were incongruent with the appellant's preferred outcome, and 1 for noncriminal cases if the preferences were congruent. Given the coding and the posited theory, we would expect to find a negative coefficient.

Analysis

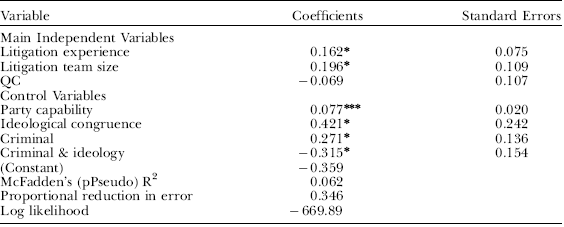

The results of the logistic regression model presented in Table 3 provide some support for the lawyer capability theory in the context of decisionmaking by the SCC. As for the strength of the overall model, McFadden's pseudo-R2 was 0.062, while the Nagelkerke was more than 0.10. Of course, all of the pseudo-R2 measures lacked the intuitive interpretation of the coefficient of determination. The more intuitive Proportional Reduction in Error for the model was 0.346. In other words, including the independent variables in the model reduces the error in predicting the probability of the Court deciding in favor of the appellant by 34.6% from a prediction based on the marginal distribution.

Table 3. Logistic Regression Estimates of SCC Support for the Appellant in Appeals, 1988–2000

n=1042 (256 missing)

* p<0.05;

*** <0.001

Looking specifically at the effects of the main independent variables, two of the three logistic regression coefficients were positive, as predicted, and statistically significant at the 0.05 level.Footnote 22 The Litigation Experience coefficient was 0.162, while the Litigation Team Size estimate was 0.196. Conversely, the QC coefficient was negative. While the relative size and litigation experience of the parties affects the Court's decisions, the designation of QC does not seem to have an effect in the population. In addition, we employed several alternative operationalizations of the QC variable (e.g., dummy variable coding), and the variables never approached conventionally accepted observed probability levels for tests of statistical inference. The correlations between the dependent variable and the various QC measures ranged from 0.01 to 0.007. Presumably, the lack of an observed statistical relationship is a function of the measure, and not the underlying concept (lawyer capability). As noted above, the designation in Canada, unlike England, reflects length of practice and public regard more than ability as an advocate. Moreover, this is consistent with the Reference Flemming and KrutzFlemming and Krutz (2002a) finding that QC designation does not influence SCC decisions at the agenda-setting stage.

While the QC designation did not affect outcomes on the merits, overall the lawyer capability model was robust. That the model would extend to the SCC should not be too surprising. Given that lawyer experience affects the behavior of U.S. Supreme Court justices (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995; Reference WahlbeckWahlbeck 1997), and based on the institutional similarities and differences between the SCC and its U.S. counterpart, we hypothesized that lawyer capability would affect the Court's decisionmaking even after controlling for party capability. For example, both national high courts have substantial docket control, as well as virtual life-tenure, and they act without threat of reversal and absent binding vertical stare decisis. More specifically, lawyers interact in a similar fashion with both courts, through oral and written arguments. Finally, since the Canadian barristers also submit books of authorities, and they have twice as much time to orally argue their case, they have more opportunities to influence the Court than their counterparts to the south.

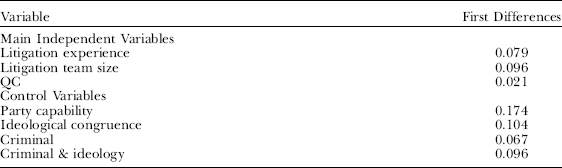

While the direction and statistical significance of the litigation team experience and size coefficients indicated that a relationship does indeed exist between litigation team capability and judicial decisionmaking by the SCC, they told us little about the substantive significance of the underlying construct. For that, we employed both numerical and graphical approaches. Initially, we derived “first differences,” presented in Table 4. The first difference technique measures the difference between the predicted values of the dependent variable for two values of an independent variable, holding all other variables constant (in this case, constant at the mean). We chose two values: one standard deviation above and below the mean (Reference LongLong 1997).Footnote 23

Table 4. First Differences for Logistic Regression Estimates of SCC Support for the Appellant in Appeals, 1988–2000

The first difference for the Litigation Experience variable was 0.079, indicating that the predicted probability of an appellant victory increases by 0.079 for a mean-centered two-standard-deviation change in independent variable. This value was the median of the seven first differences presented in Table 4, and the highest of the three litigation team variables. The Litigation Team Size had a slightly larger first difference—0.096. Among the control variables, the Party Capability variable had the largest first difference, at 0.174, followed by the Ideological Congruence variable (0.104) and the multiplicative term estimating the interaction between ideology and criminal issues.

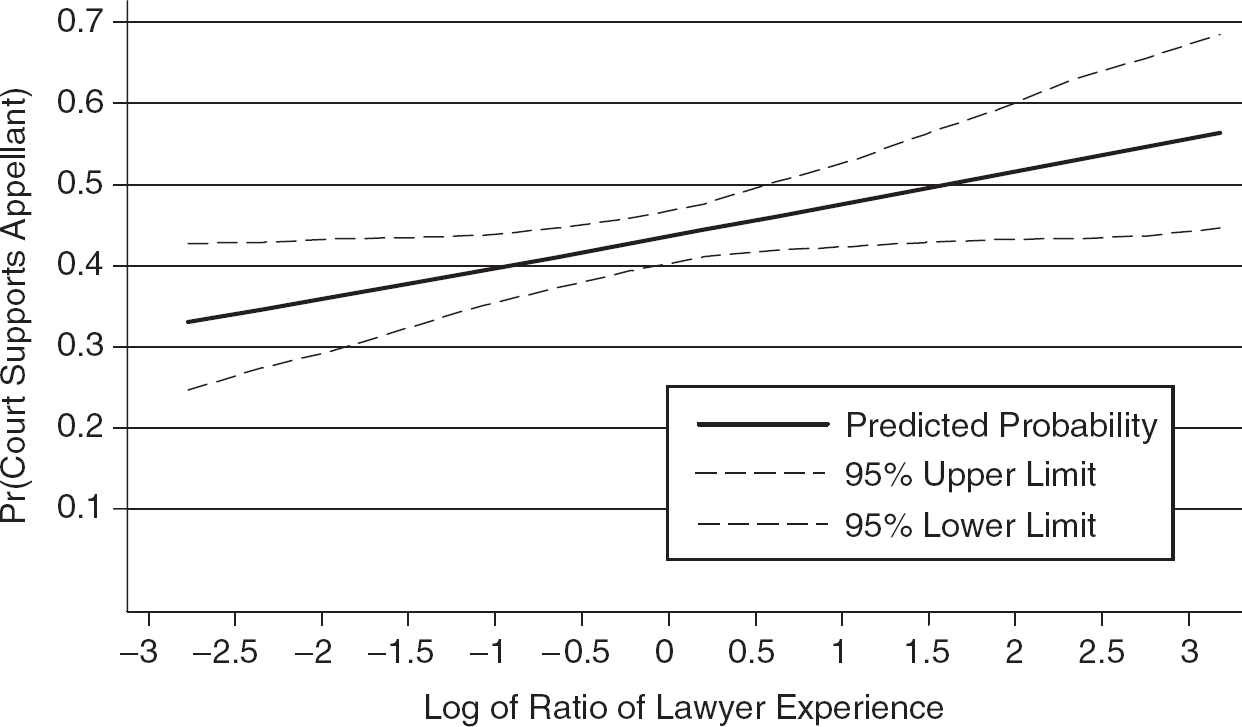

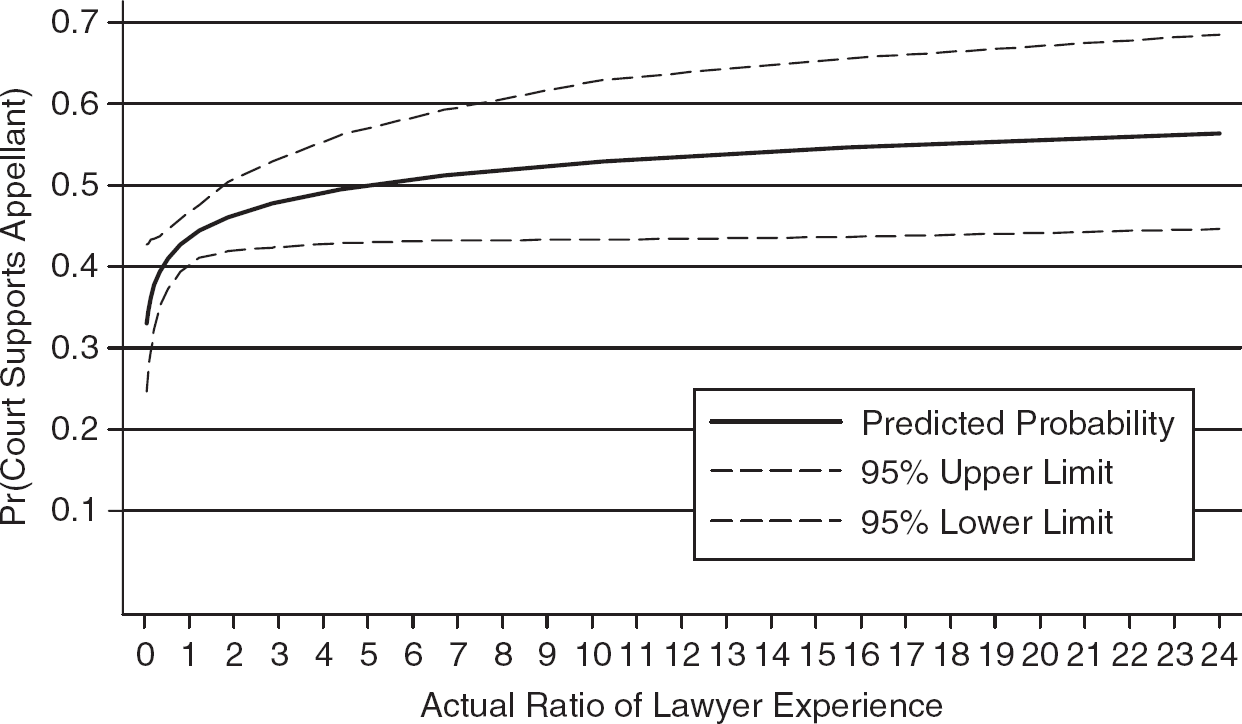

We also constructed a graphical presentation of the substantive effects of one of the main independent variables, Litigation Experience.Footnote 24 Using Spost, developed by J. Scott Long (see Reference Long and FreeseLong & Freese 2006), we plotted the change in the predicted value of the probability that the Court would vote in favor of the appellant, given a change in the Litigation Experience variable (roughly interpreted as the log of the ratio of the average experience of the appellant's litigation team experience to that of the respondent), holding the other explanatory variables constant at their means. We also used bootstrapping with 1,000 iterations to construct the 95% confidence intervals around the predicted probability line. The steadily increasing solid line presented in Figure 1 provides visual evidence of a significant relationship between lawyer experience and the Court's decisionmaking. Finally, in Figure 2, we present a similar plot with the actual, unadjusted ratio of appellant litigation team experience to that of the respondent's litigation team. Once again, the graph indicates a steady increase in the predicted probability, particularly for the lower values of the lawyer experience ratio.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of Court Support for Appellant with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 2. Predicted Probability of Court Support for Appellant with 95% Confidence Intervals.

While the controls seemed to exert more influence on the Court's behavior, at least from the first differences,Footnote 25 it is of substantive import that the statistical relationships between the two lawyer constructs, Litigation Experience and Team Size, and the SCC's support for the appellant persist even after controlling for the effects of ideology, party capability, and the issue area. Indeed, all four controls were statistically significant at the 0.05 level or higher.

In particular, given the significant nexus between party capability and lawyer capability, simultaneous statistical significance of the two sets of measures is of substantive import. Presumably, parties with superior resources (one of the criteria used to generate the hierarchy of the typology measure of party capability; see Reference SongerSonger et al. 1999) have the wherewithal to hire more capable counsel.Footnote 26 However, the impact of party capability seems to extend well beyond this one potential advantage.

Indeed, with respect to the relative weight of party capability and lawyer capability, the relative primacy of the former (as evidenced by the first differences, which are admittedly imperfect) is somewhat more surprising. In the U.S. Supreme Court, the impact of party capability is arguably a stimulus for justice attitudes (Reference SheehanSheehan et al. 1992). Alternatively, Reference Kritzer, Kritzer and SilbeyKritzer (2003) contends that party capability theory can be reduced to the advantages of governmental over nongovernmental entities.

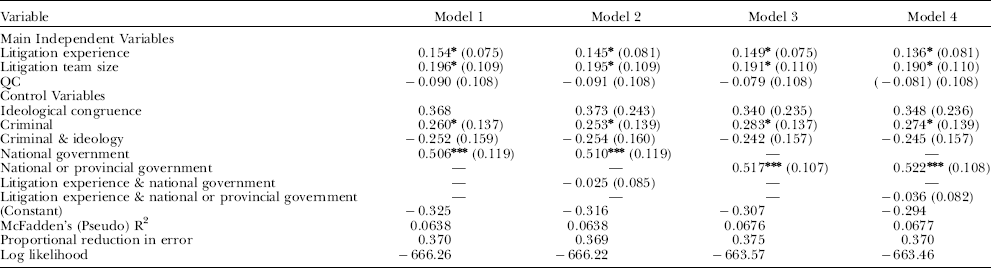

Moreover, Reference McGuireMcGuire (1998) finds that the observed and highly touted impact of the national government in U.S. Supreme Court cases disappears when controlling for attorney litigation experience. However, this is not the case in Canada. In the models presented in Table 5, the Party Capability variable is replaced by variables that take into account government primacy, in an attempt to mirror Reference McGuireMcGuire's (1998) study. In Model 1, the National Government variable is coded as 1 if the appellant is the national government, −1 if the respondent is the national government, and 0 if neither party is the national government. Model 2 includes the National Government variable, along with a multiplicative term estimating the interaction between the national government participation and lawyer experience. Models 3 and 4 have similar government participation variables, only both national and provincial governments are combined. All the other variables from the model presented in Table 3 are included in each of the four models.

Table 5. Logistic Regression Estimates of SCC Support With Government Variables (standard errors in parentheses)

n=1042 (256 missing)

* p<0.05;

*** <0.001

In Reference McGuireMcGuire's (1998) study, he found that the impact of the presence of the solicitor general's office (which is virtually synonymous with the participation of the U.S. national government as a litigant) disappears when controlling for party experience. However, in all four of the models presented in Table 5, the government variables remain statistically significant, as does litigation experience. While the observed executive success in the United States may be an artifact of the experience of counsel in the solicitor general's office, this is not the case in Canada. Of course, this could be a function of institutional variations across nations. In particular, while the relatively small (typically fewer than 20 attorneys) solicitor general's office participates in all of the U.S. Supreme Court cases in which the national government is a party, a centralized counterpart in Canada does not exist. Instead, most of the lawyers for the national government in Canada come from a local office of the Justice Department, often far from Ottawa (Reference HennigarHennigar 2001).

Conclusion

Like others before us, we have taken hypotheses developed in prior studies of the U.S. courts and applied them to decisionmaking on the SCC. Given the similar judicial processes in both systems, as well as the similar role of the lawyers in the processes, we expected that the lawyer capability theory would apply to the SCC in the same fashion that it applies in the United States. The results of our model seem to bear this out. Litigation team experience and size affect the Court's decisionmaking, even after controlling for several factors, including ideology and party capability.

Beyond the extension of the lawyer capability model to another context, the work makes three other contributions to the literature. First, we incorporated a new measure of lawyer capability: the size of the litigation team. Second, we find that, unlike in the United States (see Reference McGuireMcGuire 1998), the advantage of the Canadian governmental gorillas extends beyond the experience of the litigators. Finally, this study, like other studies of courts outside the United States, helps broaden our understanding of judicial behavior. Moreover, it augments our growing understanding of an important policymaking institution in a major industrialized nation with more than 32 million citizens.

As always, future researchers should continue to extend theories developed in the United States to other contexts. For example, other previously untested theories (e.g., the degree to which the justices adhere to precedent in cases following landmark decisions, see Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1996; jurisprudential regime theory, see Reference Lindquist and KleinLindquist & Klein 2006 and Reference Kritzer and RichardsKritzer & Richards 2002) could be tested in the Canadian context. Moreover, lawyer capability theory could be tested in other common law nations. Similarly, future researchers should consider exploring the differences in the role of legal counsel in common and civil law nations.

Future studies could also correct the limitations inherent in this one, as well as other applications of party and lawyer capability theory. For example, one of the weaknesses consistent in the long line of party capability is the roughness of the method used to measure capability. Future studies should try to directly examine the actual resources and experience of the parties. For example, one could construct a party experience variable in the same manner that we utilize to construct our lawyer experience variable. Similarly, other measures of lawyer capability (like those developed by Reference HaireHaire et al. 1999; Reference JohnsonJohnson et al. 2006; and Reference WheelerWheeler et al. 1987) could be employed in future studies.

Beyond the alternative measures of party and lawyer capability, future studies could build on McAtee and Reference McGuireMcGuire's (2007) examination of the potential conditional nature of the impact of attorney capability. They find that attorney capability matters more in U.S. Supreme Court cases when the case involves salient issues. Future research of other courts, including the SCC, should incorporate similar tests. Similarly, moving beyond the Reference McAtee and McGuireMcAtee and McGuire (2007) study, future researchers should also examine other potential interaction effects, including case complexity. It is possible, for example, that judges are more reliant on attorney explication in those cases that involve more complex legal issues.

Finally, studies of party and attorney capability are of particular importance because they inherently raise questions regarding the fairness of the judicial process. If the resources and experience of litigants affect a judge's decision, then there is a dangerous, systematic bias in the judicial system. Moreover, the bias is particularly dangerous in courts of last resort, such as the SCC. The impact of their decisions extends beyond the resolution of a particular dispute; through institutional norms, their decisions can create broad-reaching policies. To the extent that lawyer capability matters, those litigants with the resources to hire more capable legal representation can have a more significant influence on policy. Presumably, the policies will then tend to benefit those with the financial wherewithal. The fact that the SCC is insulated from democratic influences through norms of judicial independence increases the potential for widespread bias. Of course, even if the evidence in support of these theories ever becomes overwhelming, the role of correcting the flaws ultimately falls to the policy makers. However, future researchers could use comparative studies and other methods to try to determine what types of policy changes could eliminate this bias.

Appendix: Coding Conventions for Determining the Directionality of the Court's Decision (used to determine the Ideological Congruence variable)

Note: for all issues, coded missing if the decision of the national top court supports both sides in part or the ideological direction of the decision cannot be ascertained.

criminal issues:

liberal=for position of the defendant

conservative=for government

civil rights:

liberal=for position of person alleging that his or her civil rights had been violated (except in “reverse discrimination” cases)

conservative=opposite

freedom of expression and religion:

liberal=for the expansion or the protection of assertions of rights of expression and religion

conservative=opposite

private economic relationships:

liberal=for the economic underdog if one of the parties is clearly an economic underdog compared to the other

conservative=for upperdog (code as missing if no clear underdog)

torts:

liberal=for the injured party

conservative=for party allegedly causing the injury

copyrights, patents, trademarks:

liberal=for the person alleging infringement of their copyright, patent, or trademark

conservative=opposite

public law (except for public employment and government benefits) (includes taxation):

liberal=for the government

conservative=opposite

public employment and benefits:

3=for employee or the recipient of benefits

conservative=for government

family: code all as missing

disputes between levels of government:

liberal=for national government

conservative=for subnational government

missing=use for all cases involving different units at the same level or any dispute not involving the national government (e.g., city versus province)