Generating political will is often viewed as the key to changing governmental human rights behavior. This article argues that political will can only achieve so much—and that for fundamental change to occur, governments must actually become willing to change their own behavior and that of other powerful social actors. We understand willingness as governmental elites’ sincere disposition to achieve a given outcome. Sincerity, we argue, captures not only the coordinated and comprehensive steps necessary to prevent and provide redress for a human rights violation, but also the agile stance required to confront challenges and accept the costs that inevitably arise when trying to alter otherwise stable human rights behavior.

Willingness is highly difficult to come by in the issue area of human rights. The cost-benefit calculation for governments tends to favor maintaining the status quo. In this sense, governments that face intense domestic and international criticism usually take some action: they may adapt their discourse, sign and ratify treaties, change some laws, or even reform their constitutions or establish National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs). But these actions can be nothing more than strategic nods to international and domestic critics, and therefore we should not mistake them for concerted, comprehensive efforts to change human rights behavior and outcomes. There may also be times when sincere effort is thwarted by the political realities of negotiation and implementation. The conceptual framework presented in this article, we argue, helps tease out these important nuances between motivation and implementation, illuminating the often opaque space between the design and impact of policies and highlighting the real-world consequences of policymakers’ preferences.

Scholars have defined change in human rights behavior in different ways. International relations and comparative politics scholars often use large, cross-national datasets to ascertain correlation between certain independent variables (e.g., treaty ratification, civil society shaming, or international pressure) and their dependent variable of human rights behavior. They operationalize their dependent variable in widely divergent ways, including prosecuting state officials who violate human rights in domestic and international courts (Sikkink and Kim Reference Sikkink and Kim2013), changing national legislative priorities, and composite measures of human rights violations based on human rights reports (Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards2010; Fariss Reference Fariss2019; Fariss and Dancy Reference Fariss and Dancy2017; Hathaway Reference Hathaway2002) or political repression scores. The possible pitfalls of measuring changes in human rights behavior using one or a combination of these variables, which this type of large cross-national work often requires, are longstanding and well documented (Cingranelli and Filippov Reference Cingranelli and Filippov2018; Fariss Reference Fariss2019; 2; López and Stohl Reference López, Stohl, Jabine and Claude1992).

In addition to addressing problems of reliable data and inconsistent performance across human rights issue areas, this article aims to address the uncertainty in measuring human rights outcomes that comes from what we know are the strategic nods toward human rights commitment that states often give. States may sign a treaty here, change a law there, and maybe even prosecute a small number of perpetrators, but we argue that these actions are very different from a concerted, comprehensive willingness to change behavior.

Some authors have explicitly approached the issue of willingness, but they have proposed to look at it indirectly, to infer it from factors such as incentives (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2012; also see Grewal and Voeten Reference Grewal and Voeten2015; Cole Reference Cole2016) or regime type and degree of states’ material or social vulnerability. We remain unconvinced by this indirect approach to operationalizing willingness, and therefore we have developed a framework that can be used to assess levels of willingness across cases.

We apply this “willingness” framework to two of Mexico’s most recent high-profile human rights crises: violence against women and femicides, and disappearances. Both crises have inspired significant waves of domestic and transnational mobilization and pressure. In response, the Mexican government has implemented high-profile legal and institutional reforms. This study investigates the Mexican government’s responses to each of these crises by looking closely at the government’s most important legal and bureaucratic actions. We ask whether these actions amount to a true willingness to advance profound change, or whether they are better characterized as nothing more than “tactical concessions”.

We consider that a subnational and cross-temporal analysis within Mexico is an ideal environment in which to analyze, operationalize, and understand the significance of our willingness framework. Mexico, until relatively recently, was not considered to be one of the leading human rights abusers in Latin America. Despite a low-intensity Dirty War, in comparison with its South American neighbors, Mexico avoided many of the worst human rights crises of the 1950s through 1980s, including widespread extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances.Footnote 1 Significant political developments in the past 25 years, however, have led to an uptick in violence. Like the increasing violence in much of the region, however, this recent violence is not clearly perpetrated by state actors, and therefore does not fall as clearly into the traditional and historical definition of human rights abuse.

The subsequent uptick in violence is largely a result of President Felipe Calderón’s militarized approach to the drug trade. Because of this increasing violence, Mexico has become the target of intense transnational and domestic human rights activism. As a result, it has adopted numerous and highly visible legal and institutional human rights reforms (Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2009, Reference Anaya Muñoz2011, Reference Anaya Muñoz2019a; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2017, Reference Gallagher2022; Gallagher & Contesse Reference Gallagher and Contesse2022). This makes Mexico a crucial case study, ripe for theory development (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975; Gerring Reference Gerring2004), appropriate for probing our analytical framework to identify a willing government “when we see one,” and also for identifying key factors associated with the generation of willingness. An intracase comparison of two human rights crises presents interesting variations, which allow us to sharpen our theoretical insights.

While the theoretical framework to account for the generation of willingness we develop here is preliminary, we are confident that it is relevant for analyzing other “democracies in flux” (Simmons Reference Simmons2009) in Latin America, as well as in other regions of the world, that have been the target of intense transnational and domestic human rights activism and that have implemented different legal and institutional reforms in response. For instance, the Guatemalan political elite accepted the creation of the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG)—in the midst of strong international pressure against high levels of impunity and the collapse of the domestic judicial system—only to end its mandate after it proved its effectiveness (see Schwartz Reference Schwartz2019). Was the original decision to accept the CICIG a true sign of the elite’s willingness to solve Guatemala’s massive justice deficit?

In Colombia, the “false positives” scandal, in which members of the Colombian military, for professional gain, killed innocent civilians and claimed them as guerrillas killed in battle, generated international outrage, including extensive political intervention by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. In response, the government held unprecedented human rights prosecutions, and several top military officers lost their jobs. Although some convictions were later vacated or perpetrators served minimal sentences, nearly a dozen Colombian military personnel recently confessed their guilt as part of the country’s peace and reconciliation process (see Schmidt Reference Schmidt2022).

How do we parse how willing Colombian authorities have been to break historically guaranteed impunity for members of the armed forces? Our willingness theory offers a framework to address these questions—and has important implications for both activists and policymakers seeking to understand and change state human rights behavior.

This article proceeds to approach the concept of willingness and define a series of indicators. It operationalizes willingness by systematically comparing Mexico’s response to violence against women/femicides and the crisis of disappearances. It finds that the Mexican government has been significantly more willing to make meaningful changes to address and deter violence against women and femicides than disappearances. The article then discusses this variation in outcome, and on the basis of the empirical analysis, identifies a series of factors that are associated with greater or lesser levels of willingness. The article concludes by highlighting the merits of this framework to assess states’ sincere disposition to change their human rights behavior and to explain variations therein.

Willingness

International relations and comparative politics literature has extensively studied the influence of international norms, actors, and processes on the human rights practices of states. Initial studies emphasized the role of transnational and domestic activism and the pressure it generated over repressive governments (Brysk Reference Brysk1993; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink2014; Risse et al. Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink2013). The underlying argument in this literature is that transnational activism and pressure can induce change. But what kind of “human rights change” was this literature expecting to find? Profound human rights change or full compliance with the highly demanding requirements of international human rights treaties depends on multiple factors; most important, institutional capacities and state presence (Brözel and Risse Reference Brözel and Risse2013; Cole Reference Cole2015; Englehart Reference Englehart2009; O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993; Risse and Ropp Reference Risse and Ropp2013)—characteristics that fall largely outside the influence of transnational advocates.

Given this limitation, we understand that transnational human rights pressures, or activism’s central aspiration, is to generate a change in governments’ disposition to pursue human rights change. This is what we call willingness. Emphasizing willingness instead of other kinds of human rights outcomes is important because it clarifies the relevant causal mechanisms in relation to transnational and domestic activism and, particularly, because it addresses the aforementioned problem of confusing strategic state responses with “human rights change.” States may sign a treaty here, change a law there, create a new human rights–based institution, prosecute some perpetrators—but, we argue, these actions are very different from a concerted, comprehensive willingness to change outcomes.

We contend that willingness is the starting point for profound, meaningful human rights change. If governments do not really want to attain new or different outcomes, the status quo will persist. Several authors explicitly note the role of willingness as a key independent variable to explain compliance with human rights norms (Cole Reference Cole2016; Grewal and Voeten Reference Grewal and Voeten2015; Hillebrecth Reference Hillebrecht2012; Risse et al. Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink2013). However, they do not offer details as to its conceptualization, and some confound it with other notions, such as incentives. As noted above, we define willingness as a government’s sincere disposition and effort to achieve a given outcome. Such a disposition to “do what it takes” comes from preferences (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2000; Post et al. Reference Post, Raile and Raile2010). The government of country X will be willing to achieve objective Y if it has a strong preference for it. We posit that when a government responds to human rights pressures it is not immediately clear whether it is doing so because it really has a (new) preference, or because it is seeking to make cosmetic concessions in order to alleviate pressure. In other words, we do not and must not assume that a government has become willing to ultimately pursue compliance just because it has made some reforms.

Hillebrecht suggests that governments will be willing to change the status quo in human rights behavior when their interests are served by compliance, given that the costs of change (or the negative incentives) are comparatively low (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2012). But even when the incentives for positive human rights change are high (for example, in the face of strong domestic human rights mobilization and international pressure), target governments often prefer to limit their response to formal or symbolic reforms. States react to mobilization and criticism—they change their discourse, ratify treaties, reform their legislation or their institutions, implement policy programs, and even prosecute and perhaps convict some perpetrators. However, these reactions can be no more than “cheap talk” or “tactical concessions” designed to appease critics and relieve pressure (cf.). Cheap talk, furthermore, does not necessarily lead to a “spiral” of compliance (Jetschke and Liese Reference Jetschke and Liese2013). In sum, target governments may pretend to pursue change without really having the willingness to comply.

In their revised version of the “spiral model,” Risse et al. (Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink2013) propose to infer willingness from regime type and the level of material or social vulnerability—democratizing states that are economically or socially vulnerable are assumed to be more willing. Other authors propose to infer willingness from the incentives governments have to comply—a country that faces strong transnational and domestic pressures, for example, will be a willing state (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2012; also see Grewal and Voeten Reference Grewal and Voeten2015; Cole Reference Cole2016). In this way, extant human rights literature proposes to observe willingness indirectly. This study observes it more directly.

Willingness Indicators

We adapt the following framework of five indicators proposed by Derick W. Brinkerhoff (Reference Brinkerhoff2000, 242–43) to gauge “political will” in the area of anticorruption studies (Pham et al. Reference Pham, Gibbons and Vink2019; Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2019a). Of course, willingness is not a matter of “all or nothing,” but of degrees. It follows that the higher a government ranks across more of these indicators the stronger its willingness is. These indicators capture the process of formulating, institutionalizing, and implementing reform initiatives that governments take to address the problems they face (i.e., corruption or violations of human rights).

Locus of initiative

Did the reform initiative(s) come from the government, or were they introduced and advocated by outside actors? It may be more difficult to gain buy-in among state actors for agendas that are externally imposed by civil society or other nonstate actors: “imported or imposed initiatives confront the perennial problem of needing to build commitment and ownership; and there is always the question of whether espousals of willingness to pursue reform are genuine or not” (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2000, 242).

Analytical rigor

Has the government elaborated in-depth, comprehensive technical analyses of the problems in question? Have these analyses been the basis of efforts to design a comprehensive strategy or response to those problems? As Brinkerhoff stresses (Reference Brinkerhoff2000, 242), “reformers who have not gone through these analytic steps … demonstrate shallow willingness to pursue change.”

Mobilization of support

Has the government taken actions to identify, mobilize, and include different stakeholders, particularly social actors, that can endorse and support its initiatives for change? Has the government tried to build up broad and strong social and political alliances around its own initiatives to balance the opposition of groups (even within government) whose interests might be affected by the reforms? A passive government that does not proactively advocate for its initiatives to move forward but instead waits for them to consolidate on their own most probably lacks political will.

Continuity of effort

Initiatives need to have a long-term perspective, both in design and in practice. Have government initiatives been conceived and applied as one-shot endeavors or isolated concessions, or are they designed to be long-term, multistep efforts? This “includes assigning appropriate human and financial resources to the reform program and providing the necessary degree of clout over time” (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2000, 243).

Application of credible sanctions

Governments that want to successfully implement difficult reforms need to identify and apply rewards and sanctions to influence the behavior of actors “on the ground.” The key sanction in human rights cases is individual criminal accountability: willing governments are expected to show that the violation of norms will have personal consequences for perpetrators. Has the government used prosecution (or credible threats thereof) as its “principal tool for compliance” (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2000, 243)?

The STATE’S WILLINGNESS TO COMPLY

Two prominent human rights crises in Mexico were the disappearance and killings of women in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuaha, during the late 1990s and early 2000s and the current crises of disappearances, particularly in the context of the war on drugs. The focus is Mexico’s willingness to respond to each of these crises during a single administration (for femicides and violence against women, Vicente Fox, 2000–2006; for disappearances, Enrique Peña Nieto, 2012–18).Footnote 2

In the mid- and late 1990s, women, mostly young and working class, started to disappear in the industrial city of Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, across the border from El Paso, Texas. Many of these women’s bodies were later found abandoned within the city limits, often with signs of brutal physical abuse and sexual violence. At first, investigative and political authorities ignored individual demands for investigation from victims’ relatives. In response, groups of mothers formed, mobilizing and demanding justice and spawning what in due time would become one of the most dense and active transnational advocacy networks in the history of human rights mobilization in Mexico (Amnesty International 2003; Staudt Reference Staudt2008; Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2011).Footnote 3

More recently, in 2006, President Felipe Calderón (2006–12) launched Mexico’s iteration of the war on drugs. Since then, more than 85,000 Mexicans (particularly young, poor, and male, but also women and children) have disappeared at the hands of organized criminal groups and government forces.Footnote 4 The government’s preliminary response was to implicate the victims as responsible for their own disappearance by claiming that estaban en algo—they were probably involved in something nefarious leading to their disappearance—as a way of justifying the lack of investigation into these cases. While discourse has since shifted in response to widespread mobilization in Mexico and calls for accountability from the families of victims, these disappearances have also remained overwhelmingly unsolved. Then the disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Teachers’ College in September 2014 brought the issue of enforced disappearances in Mexico to the attention of the international community and sparked massive domestic and international mobilization. But despite the broad and intense national and international pressures, the students’ whereabouts remain unknown.

Mexico is one of the world’s larger democracies that struggle with high levels of human rights abuses, particularly abuses that threaten the right to physical integrity, considered by human rights scholars to be the issue area most likely to lead to significant mobilization (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink2014) and, in turn, to the most effective international pressure.

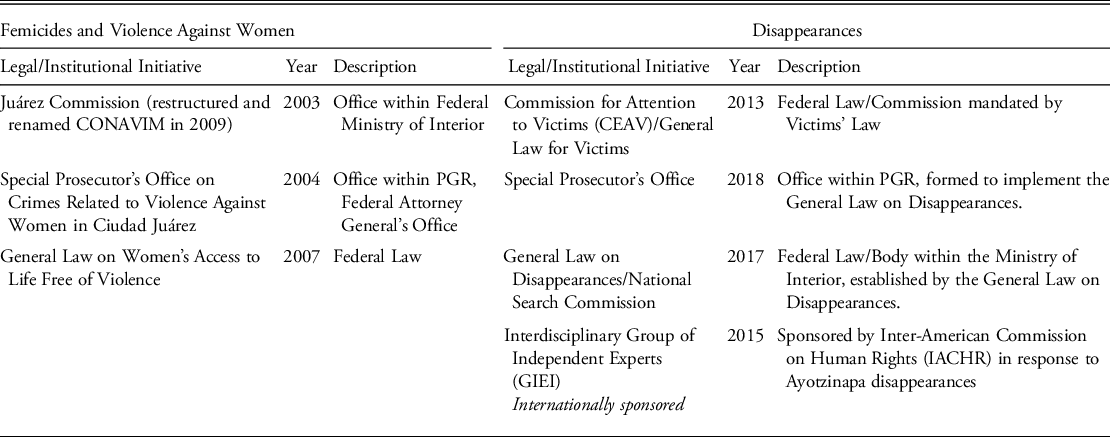

Table 1 summarizes the significant institutional responses taken by the Mexican state in response to each of the significant human rights crises this article focuses on. As the table makes clear, the Mexican federal government has taken similar actions in response to the two human rights crises studied here. In both cases, federal legislation accompanied significant bureaucratic change within the federal prosecutor’s office (Procuraduría General de la República, or PGR, recently renamed Fiscalía General de la República, FGR) and the Ministry of the Interior. On paper, the reforms and initiatives adopted for each case look quite similar: legal reforms, special investigatory offices, and commissions. Indeed, for many researchers, these responses would be coded and considered to equally reflect willingness. If anything, Mexico’s institutionalization of the international community’s participation through the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) to scrutinize the PGR’s investigation of the Ayotzinapa case might indicate even stronger willingness to address disappearances than femicides. Applying the willingness rubric, however, reveals that these apparently similar results actually belie very different degrees of willingness.

Table 1. Significant Legal and Institutional Steps Taken by the Mexican State in Response to Femicides/Violence Against Women and Disappearances

Femicides and Violence Against Women

The Mexican government’s response to domestic and international pressure to address these human rights issues can be classified according to our five willingness indicators.

Locus of initiative

The Transnational Advocacy Network (TAN, see Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink2014) that emerged around the killings and disappearances of women in Ciudad Juárez was dense and potent—it comprised the mothers of disappeared women, civil society groups from across the border (El Paso, Texas), national human rights NGOs, members of the Mexican Congress, Amnesty International, and other international NGOs and diverse human rights organizations from the UN or Inter-American systems (see Staudt Reference Staudt2008; Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2011). Notably, the Council of Europe, the European Parliament, and the Texas and US Congresses also participated in putting into motion the “boomerang effect” of political pressure (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink2014). Subsequent government actions have been convincingly explained in the literature as responses to such an unprecedented wave of human rights pressure (Staudt Reference Staudt2008; Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2011). Textual analysis of official documents and a written communication to the authors by Guadalupe Morfin, the first director of the Commission for the Prevention and Eradication of Violence Against Women in Ciudad Juárez (Juárez Commission, CPEVMCJ) further validate this claim (CPEVMCJ 2004, 7, 66; CONAVIM 2011, 5–6, 15–17, 125; PGR 2006, 26; Guadalupe Morfín, written communication).

Analytical rigor

Since 2003, different government actors—the Juárez Commission, the Ciudad Juárez Municipal Government, the PGR, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), and the state-run Chihuahua Women’s Institute—conducted or requested the elaboration of detailed analysis of the disappearance and killing of women in Ciudad Juárez. At their request, national think tanks, leading universities, and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) participated elaborating a thorough diagnosis of the situation (CPVMCJ 2004, 2005, 2006; PGR 2006; CNDH 2003; CONAVIM 2011, 2012). Additionally, the Mexican government’s official statistics agency, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), began to include the issues of violence against women and femicides as a central part of their annual national surveys.

Mobilization of support

The Juárez Commission actively promoted joint actions with a diverse group of stakeholders and allies—victims’ groups, national and international NGOs, business groups, churches, unions, universities, legislators, and diverse agencies from the municipal, state, and federal governments (CPEVMCJ 2004, 2005, 2006). Also noteworthy was the appointment of the commission’s Citizens’ Board, which was formed by high-profile members of civil society. According to Guadalupe Morfin, who headed the commission until 2006, the commission’s challenge was to “fight against interests within and outside the federal government” (Morfin, written communication). The Juárez Commission gained the trust of the mothers of the disappeared and murdered women and “constructed networks of trust with academics, journalists, government officials and activists” (Morfin, written communication). Meetings were held with the goal of advancing the investigations into individual cases, and family members, state officials, and NGO advocates sat together, achieving some significant investigatory results. The commission also worked very closely with local and federal legislators and international human rights groups.

Continuity of effort

While the response to femicides was initially formulated to focus on the epicenter of the crisis in Ciudad Juárez, as time went on the state institutions tasked with understanding, preventing, and prosecuting femicide expanded to gain national-level jurisdiction. These institutions—the National Commission to Prevent and Eliminate Violence Against Women (CONAVIM) and the Special Prosecutor’s Office for the Crimes Related to Violence Against Women and Trafficking in Persons—still exist. While this suggests continuity in the government’s policies, how have these government agencies been funded? The Juárez Commission faced severe budgetary restrictions throughout its short existence. It did not have an allocated budget of its own in 2004; extra funding announced by the federal government was never delivered; and its 2005 budget was not available until the second part of the year.Footnote 5 Despite this, it was able to grow slowly: in 2004, it had 18 employees, most of whom were contractors. In 2005, this number increased to 20 and reached 28 by 2006 (CPEVMCJ 2004, 2005, 2006; Guadalupe Morfín, written communication). The CONAVIM, which absorbed the infrastructure, budget, and resources of the Juárez Commission, has had a more robust and stable budget (CONAVIM 2011; Cámara de Diputados 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015).

Credible sanctions

During 2004 and 2005, the PGR closely scrutinized the investigative actions of state-level authorities, exerting pressure for investigations to move forward. As a result, according to the PGR, prosecutions took place in 63 percent of 379 murders investigated between 1993 to 2005, and 61 percent of those prosecuted were convicted (PGR 2006, 14, 32–37, 62). The Juárez Commission also monitored the development of criminal investigations by the Chihuahua authorities and concluded that by late 2006, impunity around the homicide of women had “declined notably” (CPEVMCJ 2006, 12).

However, according to the UNODC and national human rights NGOs, some of those prosecuted and convicted may have been innocent scapegoats, convicted and sentenced in processes characterized by a lack of due process guarantees and even the use of torture (CPEVMCJ 2005, 2006). Furthermore, the Juárez Commission reported that until late 2006, no public officers had received administrative, let alone criminal, sanctions (CPEVMCJ 2006, 2004, 2005). In addition, there were no serious investigations, and therefore no convictions, regarding the disappearance, as opposed to homicide, of women. On the contrary, it seems that prosecutorial agencies opted to minimize and sideline the issue of disappearances (CPEVMCJ 2004; PGR 2006).

Disappearances

The five indicators applied to disappearances yielded the following information.

Locus of initiative

Beginning in 2011, a consistent, though shifting, coalition of transnational and domestic activists and advocates, led by the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity (MPJD) (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2012), exerted significant pressure on the Mexican government to investigate and provide redress to victims of disappearance and other human rights violations.Footnote 6 Along with their allies in the Mexican Congress, the MPJD, human rights NGOs, victims groups, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Mexico worked tirelessly to draft legislation and construct agreements to ensure passage of the Victims’ Law and later the General Law on Disappearances. Similarly, the establishment of the GIEI was a proposal by the relatives of the disappeared students from Ayotzinapa and the OAS Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

The adoption of the laws and creation of new government agencies for victims’ rights and disappearances, along with the establishment of the GIEI, were a response from the government to the pressure by all these and other domestic and international nonstate actors. Notably, the idea for a General Law on Disappearances originated in 2011 during a fact-finding missing to Mexico of the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearance. The group recommended a comprehensive national law to address the issue (Human Rights Council 2011). Mexico City–based human rights organizations, including some of the same organizations that had been active in organizing against the disappearances and killings of women in Ciudad Juárez a decade earlier, came together to publicize the Working Group’s recommendations.

However, in a trend that we will see repeatedly throughout this period, the Peña Nieto government pulled back on initial agreements and tried to obstruct some of the key demands and proposals by civil society. The government rolled back key features of the initial Victims’ Law and the Executive Committee for Attention to Victims (CEAV) and tried to pass a General Law on Disappearances that omitted some of the key issues highly valued by civil society and international observers. In April 2016, the Peña Nieto government decided not to renew the agreement with the IACHR regarding the GIEI, terminating the group’s involvement in the Ayotzinapa investigations.

Analytical rigor

Governmental reporting about disappearances lagged behind efforts from civil society and international organs and NGOs in both timing and content. The government consistently challenged and sought to undermine external reports. The Peña Nieto administration’s hostility to external reports showed most clearly in the wake of the Ayotzinapa disappearances. The GIEI produced two systematic and in-depth reports in 2015 and 2016 (GIEI 2015 and 2016). In response, the government shifted between denial (Cohen Reference Cohen1996), hostility, and obfuscation. In March 2018, the OHCHR in Mexico affirmed the GIEI findings and issued a special report titled “Double Injustice,” which highlighted the government’s failures in the investigation, as well as the use of torture to produce “evidence” (OHCHR 2018). The Mexican government publicly challenged this UN report (Animal Político 2018), and behind the scenes threatened not to renew its agreement with the OHCHR, which would effectively kick the OHCHR out of Mexico.

To formulate policies that effectively address disappearances, the government must understand the nature and scope of the problem. A Mexican government database that gathered official information on disappeared people produced during the Peña Nieto period came under intense criticism (Turati Reference Turati2013) and had not been updated as of March 2018.

Mobilization of support

While the Mexican Senate Human Rights Commission had a good-faith and effective interaction with civil society groups, officials from the Peña Nieto administration systematically attempted to obstruct key features of the reforms advanced by civil society and international actors. The Senate Human Rights Commission invited advocates, academics, and the OHCHR to forums to discuss the adoption and reform of the laws on victims’ rights and disappearances. The president of this commission, Senator Alicia de la Peña, actively negotiated with civil society and government officials. However, top government officials stalled the negotiations for several months and challenged many of the agreements made between de la Peña and civil society (Interview with Michael Chamberlain, member of civil society negotiating team). The net result was the relegation of outside experts and civil society groups to the margins of policy implementation, despite their central role in policy formulation.

Continuity of effort

The Victims’ Law, passed in 2013, created a fund to cover financial reparations for family members of victims of disappearance and other human rights violations. The law requires that the Victims’ Fund needs to have a minimum amount of funds on hand. While this financial commitment might seem to suggest continuity of effort, during the Peña Nieto administration, the CEAV regularly spent only a fraction of the available funds.

The General Law on Disappearances provides for the establishment of long-term mechanisms and structures that, if implemented, can have a significant impact on the way the Mexican state handles cases of enforced disappearances. While the law’s recent adoption (2017) precludes a final assessment, key aspects, especially regarding the systematic documentation and strategic investigation of cases of disappearances, remain stalled.

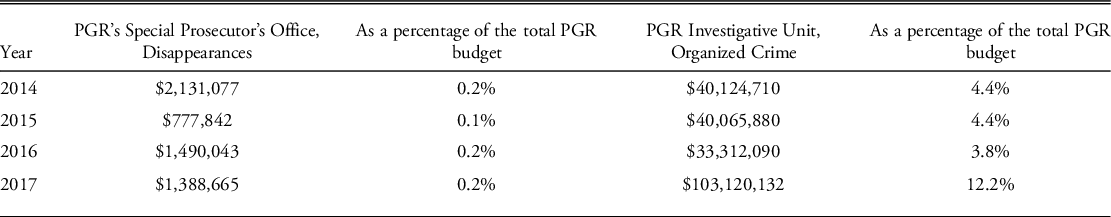

Table 2 shows that after the disappearance of the Ayotzinapa students in 2014, the Peña Nieto government did not increase the budget for the entities tasked with investigating disappearances generally. Despite the increasing number of disappearances in Mexico since 2014, the PGR’s Special Prosecutor’s Office for disappearances lost more than half its funding in 2015. Overall, table 2 suggests waning willingness. The comparison of the budget allocated to this Special Prosecutor’s Office with that given to the PGR’s Investigative Unit on Organized Crime is an illustration of the government’s preferences.

Table 2. Federal Prosecutor’s Budget Allocated to Disappearance/Enforced Disappearance vs. Organized Crime

Source: Original analysis of data from PGR/SIEIDO

Credible sanctions

A leading national NGO reported that 1,197 reports of enforced disappearances had been recorded in the state-level justice systems between 2006 and 2017. Lawyers working at the state level, however, estimated fewer than 10 convictions. In the federal system, there have been only 7 convictions out of 732 cases opened for enforced disappearance committed between 2006 and 2017 (Guevara Bermúdez and Chávez Vargas Reference Guevara Bermúdez and Vargas2018). In the case of Ayotzinapa, approximately 170 people were arrested and 129 were prosecuted. However, 77 were released in September 2019, due to the use of torture and due process violations during the investigations (Tourliere Reference Tourliere2019). The accused were members of a local gang or cartel, local police officers, and several local politicians (including the former mayor of Iguala, Guerrero, and his wife). In November 2020 a single member of the military was detained for his involvement with the disappearances, but no other members of the military, nor politicians at the state or federal level, have been charged, despite strong evidence that they knew what was happening (Gibler Reference Gibler2017).

Discussion

At first glance, the two most significant human rights crises in Mexico’s present and recent past—violence against women/femicides and disappearances—would appear to be quite similar. Both have spawned local, national, and international mobilization, and in response, the government created new commissions, laws, and offices within the Attorney General’s Office and the Ministry of the Interior.

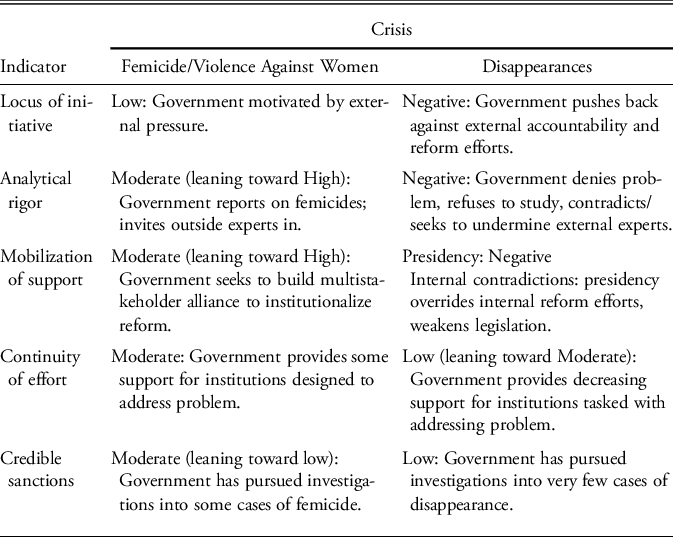

However, this article’s comparison has shown that the Mexican state has not always been equally willing to address the causes and consequences of the human rights violations it has faced (see table 3). Applying the five criteria of willingness facilitates a critical evaluation of government reform and responses.

Table 3. Willingness Indicators

Note: This table compares the femicide/violence against women and disappearances cases using the following ordinal scale of willingness: Negative, Low, Moderate, and High.

In sum, our findings around each of these criteria are as follows:

Locus of initiative

Domestic activists and their transnational allies in both cases loudly demanded that the government provide legal and institutional frameworks to support the victims, to prevent further violations, to investigate and sanction those responsible, and to allocate reparations. All the particular government actions studied here in relation to femicides and violence against women in Ciudad Juárez and to disappearances and the Ayotzinapa case were responses to pressures from local and international activists. The locus of initiative in both cases originated not within the government but from its domestic and international critics.

However, denial-style reactions (Cohen Reference Cohen1996) have been stronger in regard to disappearances. The Peña Nieto administration tried to restrict the contents of the General Law on Disappearances favored by civil society, modified the characteristics and functions of the CEAV, failed to facilitate the investigations of the GIEI and largely ignored its conclusions and recommendations, and ultimately refused to renovate its mandate. If in both situations the locus of initiative analysis shows lack of willingness, in the case of disappearances it shows an effort to resist and roll back externally led reform efforts.

Analytical rigor

The contrast is even starker in this category. The institutions created by the federal government in response to domestic and international pressure, particularly the Juárez Commission, together with the Federal Congress, were very active in studying and reporting on the challenges they faced in addressing femicides and violence against women, and sought out external experts and reports by nongovernmental actors. In contrast, the government largely failed to produce substantive reports about disappearances, instead contradicting external experts and, notably, producing “counterreports” to challenge the veracity and accuracy of the two well-documented and highly critical reports by the GIEI. Again, far from showing a willingness to seriously study and understand the crisis of disappearances, the government resorted to denial techniques that showed deep resistance to change.

Mobilization of support

The analysis shows that the Juárez Commission strove to create a dense and diverse network of interaction and interlocution with a broad array of nongovernmental and governmental stakeholders, with the idea of supporting its agenda of advancing compliance with women’s right to live free from violence. Regarding disappearances and the Ayotzinapa case, the government initially showed willingness to work with the parents of the disappeared students and their civil society allies but quickly flipped its intentions, and the government sought to undermine the legitimacy of these very actors. The president of the Senate’s Human Rights Commission showed a good degree of willingness to move important legislation forward, attempting to broker social and political support around a particular version of the victims and disappearances laws with the active participation of civil society activists and advocates. However, presidential ministries intervened and played the role of spoiler, weakening the laws from a human rights and civil society perspective.

Continuity of effort

While this indicator does not show significant willingness by the Mexican government in either case, the government has shown decreasing effort with disappearances. Consistency in the institutional responses adopted to address femicides and violence against women was clearer: agencies created to respond to these human rights challenges have now been sustained for over a decade. The budget for CONAVIM significantly increased in relation to that of the Juárez Commission, and it has been more or less stable since. This suggests some (even if limited) continuity of effort and therefore some willingness.

The picture with respect to disappearances is bleaker. While the budget allocated to CEAV was consistent (since the Victims’ Law requires this), CEAV was accused of being ineffective and biased in the way it used these resources. Significantly, the Special Prosecutor’s Office within the Attorney General’s Office tasked with searching for the disappeared has diminished over time, including in the year following the Ayotzinapa disappearances, and its budget is consistently more than 20 times less than that of its corresponding unit, which investigates organized crime. This does not suggest strong willingness.

Application of credible sanctions

The Chihuahua and federal authorities showed some willingness to investigate those responsible for femicides, particularly during the early years of the femicide crisis in Ciudad Juárez. The federal Special Prosecutors Office on Violence Against Women has been less effective, however, in turning investigations into prosecutions. These investigative efforts must be balanced with skepticism about willingness to punish those responsible, due to the use of torture, which often extracts false confessions; the fact that no state authorities have been prosecuted; and investigators’ negligence in addressing the disappearances of women in Ciudad Juárez.

For disappearances, although good data are hard to come by, the number of convictions for this crime during the Peña Nieto administration is minuscule in comparison to the tens of thousands of disappearances that were perpetrated in the country. While there were numerous arrests for perpetrators of the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students, a large number of those prosecuted have been released. Most of those arrested, furthermore, were local police and members of organized crime. The Peña Nieto government blocked an investigation into the involvement of members of the military and federal police agents in this crime, which is consistent with the pattern of impunity for members of the military or high-ranking decisionmakers in enforced disappearance cases across the country. In other words, there is no clear evidence of willingness in this category.

In sum, we have clearly found more signs of willingness in the case of femicides and violence against women in Ciudad Juárez than in that of disappearances (including the Ayotzinapa case). Not only have the authorities undertaken more serious efforts at analytical rigor and mobilization of support, together with some (though limited) continuity of effort and the application of credible sanctions in the former, but they have shown resistance and denial in the case of disappearances, particularly through the attempts to block, deflect, or frustrate the efforts by other actors to move compliance forward.

The Question of Mexico’s Willingness

These findings raise the question of why Mexican authorities have been more willing to meaningfully address femicides and violence against women than disappearances. In other words, recalling that willingness comes from preferences, why did the Fox government have a stronger preference for advancing change in the case of violence against women and femicides relative to that of the Peña Nieto administration in disappearances? Given that some international relations scholars argue that government preferences in the area of human rights can change as the result of transnational and domestic pressure and activism (Cole Reference Cole2016; Grewal and Voeten Reference Grewal and Voeten2015; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2012; Risse et al. Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink2013), we have argued that both situations studied here elicited similarly potent transnational and domestic activism, and we therefore conclude that different levels of mobilization and pressure do not account for different levels of willingness. If differences in levels of activism do not explain these divergent outcomes, Moravcsik (Reference Moravcsik1997 and Reference Moravcsik2000) directs our attention to the material and ideational interests of domestic societal groups.

In December 2000, Vicente Fox became the first president to come from the opposition to the PRI, which had ruled Mexico since 1930. If Fox’s electoral victory did not mean a full-fledged transition to democracy—since defining features of the Mexican political system, such as clientelism, corporatism, and corruption, did not change—it did bring a significant change in the governing elite. The new government not only came from a different political party but included some high-profile academics and activists who had been advocating for democracy and human rights for decades. These newcomers occupied key positions in the Fox administration, from where they advanced a new approach to human rights in Mexico’s foreign and domestic policies.

The Fox administration implemented a fundamental change in Mexico’s human rights foreign policy, abandoning the traditional PRI approach based on the principle of national sovereignty and nonintervention for one based on almost complete openness to international monitoring and scrutiny. Domestically, it created new human rights units in different ministries, established a Special Prosecutor’s Office to investigate human rights violations perpetrated during the 1970s and 1980s Dirty War, allowed the elaboration of a thorough diagnosis of the human rights situation in the country by the UNHCHR, and elaborated a detailed National Human Rights Program (Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2009; Human Rights Watch 2013). Previous research has shown that this new approach to human rights responded to an explicit attempt by the new governmental elite to “lock in” their preferences for democracy and human rights (Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2009).

Conversely, Peña Nieto led the old PRI back into the presidency after two consecutive terms of prominence for Fox’s National Action Party (PAN). Domestically, the Peña Nieto administration was widely criticized for continuing the militarized security policies established by President Calderón and failing to mitigate the ballooning human rights crisis in Mexico. In foreign policy, although the Peña Nieto government did not cancel the policy of openness, it provoked intense tensions and confrontations with international human rights critics, including the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances, the IACHR, and the GIEI (Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2019b).

Levels of willingness also vary according to the characteristics of the human rights situation per se. The extant literature argues that levels of transnational pressure that emerge around particular human rights situations depend, inter alia, on the characteristics of the victims involved. Victims who are perceived as “innocent and vulnerable” will elicit more empathy from broader audiences (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink2014, 26–28; Sikkink Reference Sikkink1993, 423–28; Burgerman Reference Burgerman2001, 31, 38-40, 45–47; Brysk Reference Brysk1993, 270–71; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2004; Price Reference Price1998; Anaya Muñoz Reference Anaya Muñoz2011). This suggests that domestic societal actors will also be more inclined to sympathize with human rights agendas on which victims are perceived as clearly innocent and vulnerable.

The victims of femicide in Ciudad Juárez were largely young, poor, working women, and the transnational and domestic advocates that mobilized in this case successfully framed them as sympathetic and blameless. While many young and poor women have also been victims of disappearance in Mexico, a majority of the victims of this crime—nearly 70,000—are young male adults. Regardless of gender, the government has actively sought to portray victims of disappearances as in some way culpable for their fate. Calderón began this practice, claiming that the overwhelming number of victims of drug war violence were themselves involved in the drug trade, and Peña Nieto continued this—famously claiming that the disappeared students from Ayotzinapa were radicals and rabble-rousers. While the families of people who have been disappeared have mobilized to contradict this narrative (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2022), the government’s framing continues to shape much of the public’s perception of those who are disappeared. Broadly speaking, these different frames result in higher levels of empathy from the public, public opinion leaders, commentators, and government actors for victims of violence against women and femicide than for disappearances.

Our comparison further suggests that the perpetrators’ identity—whether they are state agents or linked to the state—also plays a role in generating willingness. Women in Ciudad Juárez were abused, tortured, disappeared, and brutally killed by (mostly) nonstate actors. In disappearance cases, on the other hand, state actors—often working with drug-trafficking organizations (DTOs) in some capacity—play a more direct role as perpetrators, and there is a commonly held (but perhaps rarely stated) fear that if investigators push too far on an investigation, they may stumble upon state actors—something which would be dangerous for them professionally and personally.

Thus, whereas in femicides/violence against women the state fails to protect victims and fulfill their right to justice, in disappearances state actors are much more likely to be the perpetrators. Although from the point of view of international human rights law, state responsibility is clear in both cases, from a judicial, reputational, and political perspective, the cost of revealing the direct involvement of state actors in criminal behavior by investigating or punishing disappearances is greater than those involved in the acknowledgement of incompetence or indolence or the claim of lack of resources.

Conclusions

This article has argued that the fact that governments adopt or reform laws or create new agencies in response to pressure “from above” and “from below” (Brysk Reference Brysk1993) does not indicate that they are truly willing to incur the costs required to change entrenched patterns of human rights violations. This implies that in a constellation of human rights crises, where talk is often cheap and violence and impunity abound, there are meaningful differences between “sincere” and “insincere” government reactions to domestic and transnational pressure. Therefore, this article emphasizes the need to explicitly explore, through rigorous analysis (based on the use of a specific set of indicators), whether legal and institutional innovations are mere “tactical concessions” (Risse et al. Reference Risse, Risse-Kappen, Ropp and Sikkink1999) or signs of a sincere disposition to advance meaningful human rights change.

By looking deeper into who leads reform efforts, how the government studies and documents the problem, how the government builds (or does not build) political coalitions around the issue, whether the government provides the institutional and financial support for the bureaucracies tasked with addressing the issue, and whether there are legal sanctions for the perpetrators of human rights abuses, this study sheds new light on how we should understand these human rights reforms and what we should expect from them. This demonstrates the necessity of a more nuanced understanding of human rights outcomes in general, and the concept of willingness specifically, to holistically gauge government responses in the area of human rights.

The article has highlighted the finding that levels of willingness vary across cases or situations. It has shown that the Mexican government was more willing to address femicides and violence against women than disappearances. Establishing this outcome allows us to reflect on the reasons for this divergent governmental treatment of these human rights crises. We argue that willingness in the area of human rights depends on the levels of transnational and domestic activism and pressure (which, in our comparison, remained constant across the two cases), the underlying broader preference for human rights of the governmental elite, the characteristics of the specific human rights that are violated, and the political and security implications associated with different perpetrator identity. We find that significant levels of domestic and transnational activism and mobilization are not sufficient to generate willingness. All else being equal, willingness will be greater in cases in which governments have an underlying preference for human rights, victims are perceived as innocent or vulnerable, and direct perpetrators are not state agents.

A more nuanced analysis of the set of actions and institutional changes taken in response to a human rights crisis is an important tool for scholars tackling the crucial question of how, and whether, governments make progress on the crucial issues of human rights, violence, and impunity. As this article suggests, this framework could be used to assess the extent to which responses like establishing the CICIG in Guatemala or the prosecution and accountability efforts of the false positives scandal in Colombia are rooted in their respective government institutions or are single efforts meant to alleviate pressure rather than to address the underlying causes of the rights abuses. By sorting through and contextualizing governmental willingness, we are then able to direct the analysis to why governments take (or fail to take) effective action to address and prevent grave human rights abuses—a central question for both scholars and citizens.