1. Introduction and context

This report presents how a National Professional Development grant project team at a Midwestern university prepared and delivered the first phase of virtual professional development (PD) for preservice teachers and clinical faculty in August 2021. The online PD focused on raising teacher awareness of raciolinguistic ideologies (Flores, Reference Flores2019; Flores & Rosa, Reference Flores and Rosa2015; Rosa, Reference Rosa2016), translanguaging (García, Reference García2009, Reference García2011), immigration experiences of The book of unknown Americans (Henríquez, Reference Henríquez2014), La frontera (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Alva and Navarro2018), and introduced content-enhanced language objectives (CELO). Data provided by the College of Education and current course programming indicated that there was a gap in the preparation of secondary preservice teachers (SPTs) when teaching content lessons to emergent bilingual learners (EBLs) compared with the national norms. Thus, the three researchers prepared and implemented Grand Seminar 1 to explore their knowledge of EBL demography and enrich their awareness of EBLs’ race, language, and culture.

The SEETEL (Strengthening Equity and Effectiveness for Teachers of English Learners) team designed Grand Seminar 1 to be given virtually due to the context of the COVID 19 pandemic and restrictions on large gatherings. Previous research has indicated that virtual teaching PD is most effective when teachers’ immediate teaching needs are met, and when the PD is specific and offered by experts who may not be found locally (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Phalen and Moran2016). After working with language teachers, Giraldo (Reference Giraldo2014) noticed the importance of a needs-analysis to design PD, connecting research and theory to practical classroom applications, and setting up time for reflection and follow-up; similar findings were also identified by Powell and Bodur (Reference Powell and Bodur2019). PD for secondary teachers focusing on teaching and learning with EBLs should support development of understanding of new language acquisition, cultural awareness, and sustained collaborative teaching methods (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Samimy and Romstedt2010). The current study builds on these research findings and contextualizes preservice secondary teachers’ growing understanding of EBLs within the virtual realm.

2. Methods

2.1. Attendees of Grand Seminar 1

The preservice teacher attendees represented all program areas. In terms of the breakdown of the certification areas, we would put 49 SPTs (math, science, social studies, and English) since they were this study's focal participants; they were mostly white, monolingual, and female. Of the remaining attendees, 20 were in special areas (physical education, art, music, Spanish) of preparation, and 122 were in elementary education majors. Both previous research (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Samimy and Romstedt2010) and the needs assessment from the College of Education had indicated PDs needed to target SPTs to enrich their awareness of EBLs’ race, language, and culture for the content teaching. Clinical educators, who provided instruction or supervised preservice teachers during their practicum courses across all programming levels, also attended.

2.2. Format of Grand Seminar 1

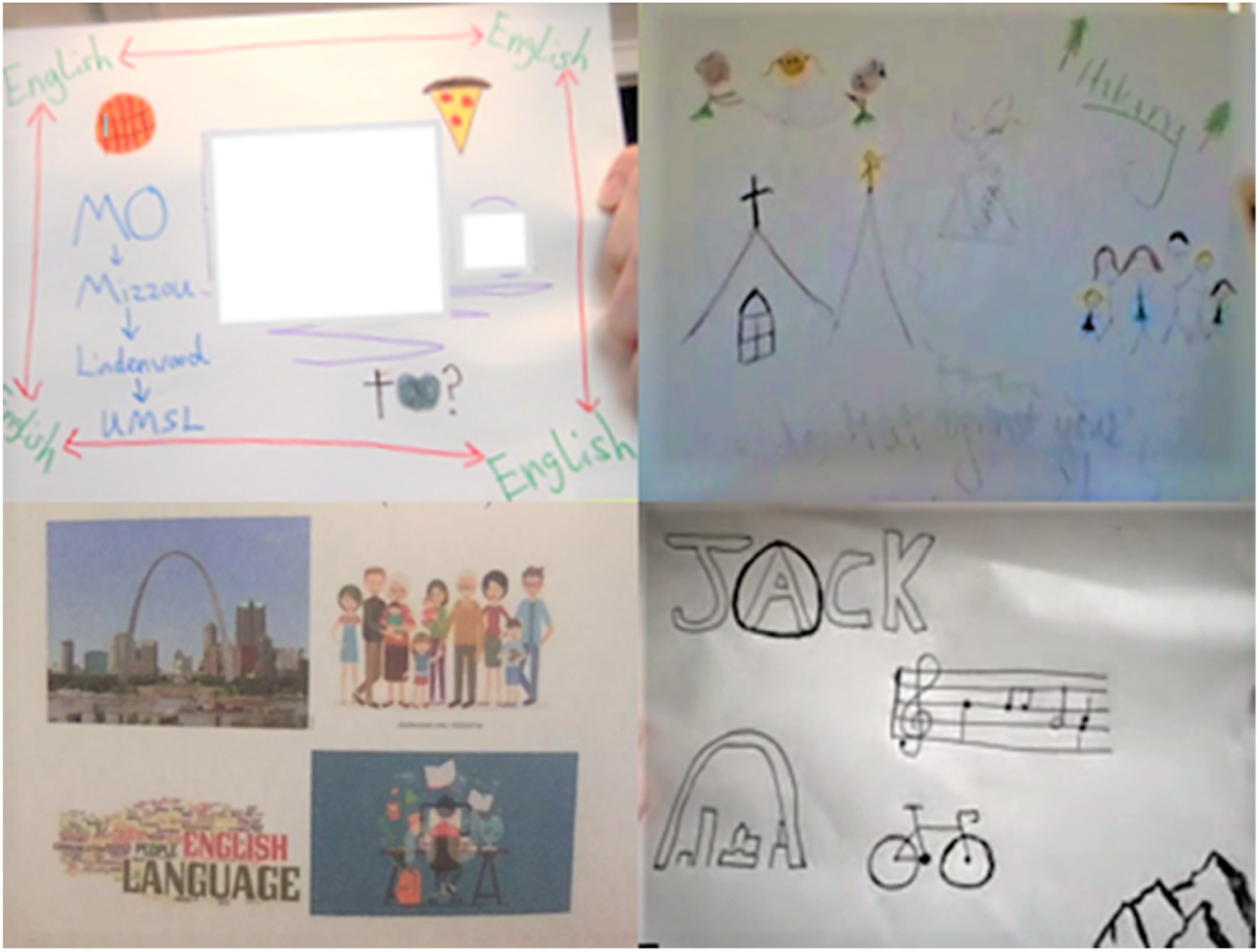

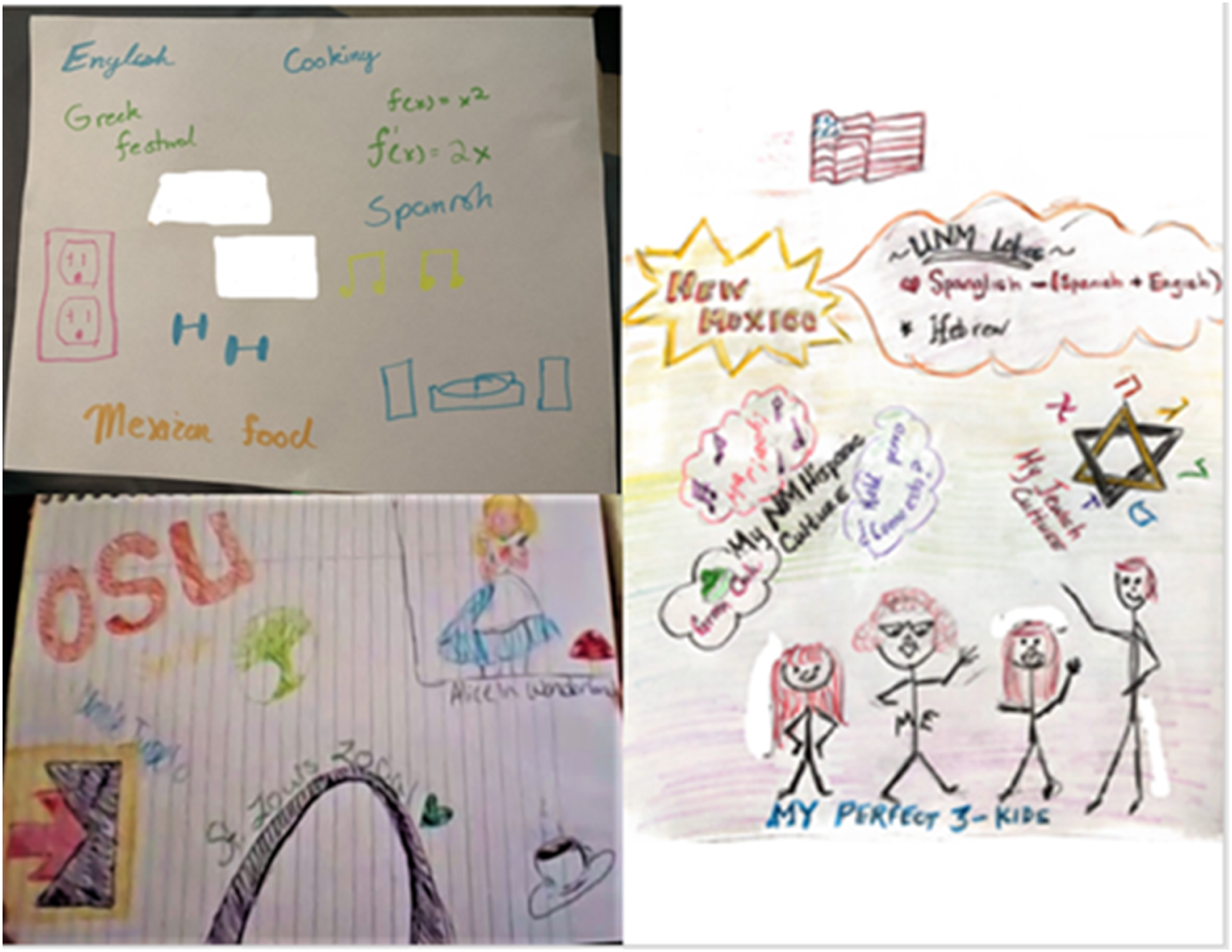

Grand Seminar 1 was a three-hour PD session on ‘What's race, language, and culture got to do with EBLs’ content learning?’ provided to 191 preservice teachers, nine clinical educators, and two faculty members. The PD included both asynchronous (pre-work) and synchronous components. For pre-work, attendees were asked to read three chapters in Christina Henríquez's (Reference Henríquez2014) The book of unknown Americans, view a YouTube reading of La frontera (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Alva and Navarro2018), and watch a YouTube broadcast of a translingual social studies lesson on immigration. The synchronous Grand Seminar PD introduced attendees to trends and facts about immigration; modeled and asked attendees to create collages (see samples in Figures 1 and 2) that conveyed cultural, racial, and linguistic identities; utilized conversations in La frontera (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Alva and Navarro2018) to illuminate and remedy cross-cultural miscommunications; employed a showcase translingual lesson on immigration to introduce preservice teachers to CELO; and prepared attendees for pre-work for Grand Seminar 2 (approximately one month later). Throughout Grand Seminar 1, attendees were asked to respond to questions in the chat in order for the PD to progress collaboratively. The SEETEL team utilized breakout sessions for two PD activities: creating and sharing of identity collages and viewing and evaluating the showcase immigration lesson and CELO utilizing a rubric. Research and theory were melded into the chat discussion topics and the breakout activities. The format and design of Grand Seminar 1 was influenced by research on PD for teachers (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Phalen and Moran2016; Giraldo, Reference Giraldo2014; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Samimy and Romstedt2010), the needs identified by the College of Education to target EBL teaching and learning theory and strategies to SPTs, and the areas identified by attendees in the chat throughout the PD.

Figure 1. Social studies teacher collages

Figure 2. Math teacher collages

2.3. Research questions and data analysis

As Grand Seminar 1 was the first phase of PD for SPTs on content teaching, we sought to determine their initial understanding of EBLs’ Funds of Knowledge (FoK), intersectionality of race, language, and culture in terms of equity and excellence for EBLs. The following questions guided this research:

• What are the goals and objectives of SPTs in relation to this PD?

• How do SPTs perceive EBLs? What discourse do they use to talk and write about EBLs?

• What connections between excellence and equity do SPTs make?

• What topics in racially, linguistically, and culturally inclusive teaching do preservice secondary teachers want to learn more about?

To shed light on these questions, we collected SPTs’ data throughout the PD, including responses in chat, video recorded large and small group discussions, and the collection of artifacts (preservice teacher identity collages and small group discussion notes on the translingual immigration lesson). While coding of the video recorded discussions and of collages is still ongoing, we have completed open coding and collapsed codes into three themes (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana2018) of the responses in chat. The SPTs responded to several questions throughout the presentation in a Waterfall format so that all responses appeared at the same time; the questions included their objectives and goals for attending this session, their responses to hearing accents, their reflections on cross-cultural miscommunications, and future topics they would like to learn more about.

3. Initial findings

Initial open coding resulted in 21 codes: Learners, Context, Welcoming, Teaching, Named Race and Ethnicities, Equity, Personal Growth, Achievement, Deficit Lens, Culture, Language, Content and Language Integration, FoK, America, Immigrant Voice, Intertextual Content Learning, Immigration Trends, Topics for Enrichment, EBL instruction, Racialized Ideologies/Systems/Institutional Racism, and Cross-cultural (mis)understanding. Within the codes, sub-codes were identified, defined, and connected to examples from secondary preservice teacher chat responses. After the team open coded the SPTs’ responses to the questions in chat, the team met and collaborated to collapse the codes into three themes: Learners, Content & Learning in Local Contexts, and EBL Education.

Coding the responses in the chat revealed that SPTs would like to know more about translanguaging, raciolinguistic ideologies, immigration experiences and facts, translingual teaching and communication strategies, ways to support the success and achievement of EBLs, and developing greater cultural awareness of EBLs.

3.1. SPT goals and objectives

The SPTs indicated that they were open to learning how they could better teach and connect with students who are racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse. Most were not specific about their objectives, frequently stating comments such as they would like to ‘learn more about different ways to engage all types of learners’ (Adam, middle school science). However, some of the SPTs provided greater context to their motivation for learning about EBLs, including ‘I would like to learn how to better teach students from all backgrounds and ethnicities not only in the classroom, but in the real world’ (David, high school math) and ‘To gain perspective that I didn't previously have before as a white woman who only speaks English. To be aware of concerns and struggles that EBLs have I may currently be unaware of’ (Lindsey, high school social studies). The comments of David and Lindsey indicated contextual awareness of systemic barriers based on race, language, and culture that existed in both classrooms and in society at large. These comments were cross-coded under EBL teaching (personal growth, white perspective, and equity) and learners (named race, institutional racism). In planning the second Grand Seminar, the team will further explore these comments by engaging SPTs in an iceberg activity of seen and unseen characteristics of characters in The book of unknown Americans (Henríquez, Reference Henríquez2014) and by asking the poll questions that will require the preservice teachers to interrogate their privileges (i.e., access, resources, benefits that are inequitably distributed amongst people).

3.2. Perception of EBLs

The SPTs typically used abstract language to talk about EBLs; they employed words such as ‘diverse,’ ‘all students,’ ‘all learners,’ ‘the student population,’ ‘cultures and languages of all students,’ and ‘every child’ when first asked about EBLs. No SPT discussed previous experience or connection to a specific EBL that they had encountered in their personal, social, or educational histories. Dylan, a high school social studies preservice teacher, acknowledged that teaching EBLs was ‘a subject [he] ha[d] little experience in.’ Comments seemed to indicate the lack of individual personhood (i.e. someone's sense of self and the rights, access, benefits, and distinctiveness that society positions them of having) attributed to EBLs. The SPTs did not seem to have the previous experiences necessary to think about the identities of bi/multilingual students. Further, some SPTs used descriptions such as ‘these students’ (Daniel, high school social studies), or ‘students who may require extra needs’ (Allan, high school ELA), and stated that ‘I would need to know just how much English language EBLs know so that I can appropriately teach them’ (Will, middle school science). These comments demonstrated a more overt deficit lens when considering the identities, attributes, and assets of bi/multilingual students. Daniel, Allan, and Will have mentioned deficit differences between EBLs and their peers. These findings guided the SEETEL team to require the preservice teachers to gather demography information on at least one EBL at their practicum placement so that they could learn more about an individual EBL (home language, home country, interests, strengths based on ACCESS scores, etc.) and incorporate this information into a teaching objective, activity, and assessment for Grand Seminar 2.

3.3. Connections between excellence and equity

Only a few of the SPTs discussed and named equity in a concrete manner. For these preservice teachers, excellence and equity connected in a way that included ‘understanding that each learner is unique’ (Ben, high school social studies), connecting content and language teaching to students’ home language and ‘their personal experiences’ (Taylor, high school biology), maintaining expectations for all students, and providing learning opportunities ‘through whatever mode in which they are most likely to succeed’ (Mike, high school social studies). These preservice teachers wrote about the individual learning styles, preferences, experiences, and languages of bi/multilingual students; their quotes indicated their connection between excellence and the equity provided to the needs of learning more about EBLs. The other SPTs did not make direct connections to equity and excellence. These comments and the absence of comments led the SEETEL team to design a translingual and transmodal lesson exemplifying equity in teaching and learning strategies and how it connects to successful teaching objective completion.

3.4. Topics for Grand Seminar 2

At the end of Grand Seminar 1, the SEETEL team asked the preservice teachers what topics they would like to learn more about in terms of culturally, racially, and linguistically inclusive teaching and learning; SPTs mentioned: (1) implementing translanguaging, (2) raciolinguistic ideologies, (3) immigration information and process, and (4) incorporating language modalities into lessons. Based on the responses, we crafted prework that the preservice teachers need to complete before Grand Seminar 2, that is, reading The book of unknown Americans, and creating EBLs’ demography Google Slides. The researchers created multiple activities to engage the teachers using inquisitive strategies and cooperative learning strategies at breakout rooms, polls, and ‘waterfall’ strategies at chat. In addition, the researchers created a showcase translingual (French and English) vocabulary teaching video that incorporates standards-based and evidence-based teaching with CELO.

4. Reflections from Grand Seminar 1

The importance of PD when targeting SPTs had been addressed previously since they demonstrated the gap in awareness of race, language, and culture of EBLs compared with that of elementary preservice teachers in research (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Samimy and Romstedt2010). Initial findings in this study reaffirmed the gap in the preparation of SPTs. In their chat responses, most SPTs utilized faceless and colorless language when talking about EBLs, at times with a deficit lens judging them only based on English ability. While SPTs, in general, did not demonstrate previous knowledge and experience working with and talking to EBLs, they did indicate willingness to learn specific strategies (translanguaging, use of language modalities) to teach and to welcome EBLs in their classrooms. Grand Seminar 1 might be the first step in supporting the SPTs in their development of the mindset and practices necessary for EBLs’ content learning.