INTRODUCTION

Sociolinguistics in the era of globalization has shifted its focus from traditional approaches to the study of language in society to postmodern ones that enable scholars to capture the emerging complexities of social and linguistic behavior brought about by the mobility of people and resources (Jacquemet Reference Jacquemet2005; Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010; Coupland Reference Coupland and Coupland2010). Within this new paradigm, some scholars have focused on investigating social (inter)action on the internet and online platforms (Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2006; boyd Reference danah2010; Barton & Lee Reference Barton and Lee2013). This era of online communication can be understood in terms of vernacular globalization (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1996), where the internet and its affordances have offered actors an increased agency enabling them to be actively involved in the (re)construction of new norms of semiotic behavior, and hence rendering online social media into an inherently polynormative space (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2018). These bottom-up processes of (re)constructing new norms in online spaces become particularly visible in the emergence of new orthographic conventions/norms which are enacted and policed by various actors (Blommaert, Kelly-Holmes, Lane, Leppänen, Moriarty, Pietikäinen, & Piirainen-Marsh Reference Blommaert, Kelly-Holmes, Lane, Leppänen, Moriarty, Pietikäinen and Piirainen-Marsh2009; Leppänen Reference Leppänen, Hotz-Davies, Kirchhofer and Leppänen2009; Leppänen & Peuronen Reference Leppänen, Peuronen, Martin-Jones, Blackledge and Creese2012). In this article, I focus on the specific case of ‘hekasreh’—a new online Farsi orthographic norm—and analyze Iranian social media users’ discursive positionings relative to this new orthographic practice. Specifically, I illustrate how Iranian Twitter users orient to different centers of authority in order to (il)legitimize these orthographic norms, emphasizing the complex and polycentric nature of (inter)action and sociolinguistic practices on online platforms.

In investigating sociolinguistic normativity, recent scholarship has used Bakhtin's (Reference Bakhtin1981) notion of chronotope (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2017, Reference Blommaert2018; Karimzad Reference Karimzad2020). Chronotopes are time-space-personhood configurations that organize social information and contextualize discourses in interaction and meaning-making (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981; Agha Reference Agha2007; Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015). They are normative in the sense that any particular chronotope encapsulates certain norms, which guide actors’ social behavior, and are also loaded with different orders of morality and indexicality which make them also function as sets of evaluative criteria for others’ behavior (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2017; Karimzad Reference Karimzad2020). Building upon Karimzad's (Reference Karimzad2020) chronotopes of normalcy, I argue for a chronotopic understanding of orthographic norms on social media, illustrating how they are linked to images of people situated in particular times and spaces, and how social actors invoke these chronotopic images when positioning themselves relative to the newly constructed norms.

Internet, and especially social media, use in Iran has considerably increased in recent years. As a consequence, new online sociolinguistic practices and norms are constantly created, changed, and updated by social actors. One of these norms is the case of ‘hekasreh’. ‘Hekasreh’ is a new Farsi orthographic norm that originally started on social media and has now seeped over to offline contexts as well. Not surprisingly, this innovation has created controversial debates on social media, especially Twitter, with two more vocal groups who, in the broad sense, align or disalign with the practice. I present data to demonstrate how these tweeters’ polycentric orientations situate their positionings on a spectrum that encompasses an array of differently scaled online and offline chronotopes of normalcy. Specifically, I show that while tweeters who disalign with the new ‘hekasreh’ orient to several different centers to claim authority, their orientations tend to fall somewhere in the domain of larger-scale offline and ‘traditional’ chronotopes (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015). In contrast, the justifications of those who align with the new ‘hekasreh’ fall on a different end of the spectrum that draw on differently-scaled online chronotopes associated with ‘modernity’ (cf. Dick Reference Dick2010; Koven Reference Koven2013). I further demonstrate how through these invocations, tweeters construct an iconic image (Agha Reference Agha2005; Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000, Reference Irvine, Gal and Duranti2009) of the group they are disaligning with, which they then use as a lens to evaluate their practices and identities.

Through a chronotopic analysis, this study presents a more complex understanding of normativity, agency, and the sociolinguistics of social media. It also provides empirical evidence that sheds light on the online-offline nexus (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2018; Szabla & Blommaert Reference Szabla and Blommaert2018) by illustrating the overlapping and dialogic nature of online and offline chronotopes revealed through the actors’ polycentric orientations. Moreover, by closely examining the argumentative dynamics of the chronotopic work done by the tweeters, I argue for more dynamic conceptualizations of power and chronotopes by demonstrating the creative and agentive ways the so-called less powerful and less accessible chronotopes are invoked to claim authority in the arguments (cf. Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018). Finally, given the fact that studies investigating the sociolinguistic effects of globalization in Iranian communities have mostly focused on the offline linguistic practices of Iranian migrant communities (e.g. Karrebæk & Ghandchi Reference Karrebæk and Ghandchi2015; Bozorgmehr & Moeini Meybodi Reference Bozorgmehr and Moeini Meybodi2016; Karimzad Reference Karimzad2016, Reference Karimzad2018), this study offers a clearer picture and a deeper understanding of the consequences of vernacular globalization that have led to the bottom-up construction of new norms in the context of social media in Iran.

INTERNET, POLYCENTRICITY, AND THE CHRONOTOPE

The era of globalization, due to the mobility of people and resources and the new technological advances, has brought along complexity and unpredictability. In an attempt to achieve a more dynamic understanding of language in globalization, sociolinguists have focused on the impacts of these globalization processes on people's language use and linguistic practices (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2003, Reference Blommaert2010; Heller Reference Heller2003; Jacquemet Reference Jacquemet2005; Coupland Reference Coupland and Coupland2010; Pennycook Reference Pennycook and Coupland2010; Park & Lo Reference Park and Lo2012; De Fina & Perrino Reference De Fina and Perrino2013; Hall Reference Hall2014). This context of globalization, as many argue, is characterized by polycentricity, mobility, and complexity. Polycentricity, in particular, refers to the multiplicity of centers that simultaneously guide the communicative behavior of social actors and come with their own sets of ordered indexicalities and norms (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010, Reference Blommaert2018). Hence, a polycentric context is inherently a polynormative one. Since the internet and especially social media, as a platform of social (inter)action, is the epitome of this polycentric context of globalization where multiple sets of norms exist, interact, and change synchronically, social media and the interaction therein has recently been of interest to many scholars (e.g. Zappavigna Reference Zappavigna2011; Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2015; Chiluwa & Ifukor Reference Chiluwa and Ifukor2015).

Among social media platforms, social networking sites (SNS), such as Facebook, Twitter, and so on specifically create a platform for people to (co)construct different online identities (boyd Reference danah2014) and online communities of practice through which they find the opportunity to creatively voice their opinions about a myriad of online and/or offline issues in ways that were never possible before. Along the same lines, many scholars in the field maintain that, as opposed to the tendency to think of online and offline contexts as two completely separate arenas, the identities performed on the two platforms, as well as the ways in which they are performed, are not completely separate. In fact, online and offline contexts seem to be in constant interaction with each other, shaping and reshaping one another (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2018; Szabla & Blommaert Reference Szabla and Blommaert2018). This can be seen, for example, through how certain linguistic practices seep into offline contexts from online platforms and vice versa. Studying the sociolinguistic phenomena that occur in the context of this online-offline nexus (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2018) calls for an explanatory analytical tool that can capture the complexities inherent to such contexts. To overcome this challenge, some researchers have, very recently, adopted Bakhtin's (Reference Bakhtin1981) notion of chronotope as a tool to analyze sociolinguistic phenomena in the era of globalization and online communication (e.g. Procházka Reference Procházka2018; Lyons & Tagg Reference Lyons and Tagg2019; Sinatora Reference Sinatora2019).

Chronotopes are time-space configurations peopled by certain identities or personhoods (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1981; Agha Reference Agha2007; Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015) that get (re)constructed and adopted in processes of encoding and decoding meaning in social interaction. Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2017) refers to these time-space-personhood bundles as ‘mobile contexts’ associated with certain norms, identities, and indexicalities that are (re)constructed through interaction. Socialization, in fact, involves a variety of (re)chronotopization processes (Karimzad Reference Karimzad2020) as chronotopic images get constantly updated through social interaction and are added to actors’ communicative repertoire guiding their social and sociolinguistic behavior, interpretation, and evaluation in future interactions. These chronotopic images operate at different scale levels; that is, they are organized within and across a scalar system which determines their scope of recognizability and communicability (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015), or, in other words, their accessibility. Indeed, the differently scaled chronotopes are linked through fractal connections where orders of indexicality from higher scales get projected onto ‘infinitely detailed’ lower-scale chronotopes and thus ‘we see chronotopes nested within chronotopes’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2017:97). Focusing on this conceptualization of chronotopes as fractally scaled semiotized images of contexts associated with various levels of fractal detail, Karimzad (Reference Karimzad2021) introduces the notion of chronotopic resolution and argues for the utility of a chronotopic-scalar approach in studying sociolinguistic phenomena. Such an approach allows for a higher-resolution and detailed analysis of the dynamicity of meaning-making processes in interaction by capturing and unpacking the links across chronotopes and/or across scales (see Karimzad Reference Karimzad2021).

Given the analytical potential of chronotopes, many sociolinguistic notions (e.g. language ideologies, identity (work), context and contextualization, normativity, etc.) have been re-examined through a chronotopic analysis (e.g. Dick Reference Dick2010; Koven Reference Koven2013; Woolard Reference Woolard2013; Karimzad Reference Karimzad2016; Blommaert & De Fina Reference Blommaert, De Fina, Fina and Wegner2017; Catedral Reference Catedral2018; Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018). Particularly relevant to this study is Karimzad's (Reference Karimzad2020) re-theorization of sociolinguistic normativity through the lens of chronotopes (see also Blommaert Reference Blommaert2017, Reference Blommaert2018). Introducing chronotopes of normalcy, Karimzad views normalcy as ‘a set of scalar and chronotopic relations’ (Reference Karimzad2020:108). He argues that understandings of normal behavior, at different semiotic levels including language choice, ‘are dynamically constructed and organized in relation to times, spaces, and types of people involved in the interaction’ (Reference Karimzad2020:108). Karimzad further maintains that it is through accordance with or deviation from such chronotopic images that specific semiotic behavior gets evaluated as normal or not. This propels sociolinguists to investigate the chronotopic organization of normativity on a variety of semiotic levels, including orthography, especially in new communication platforms where technological affordances have led to emergent complexities in social actors’ interactional patterns.

In adopting chronotopes as an analytical tool, one aspect to consider is the argumentative nature of chronotopic work in interaction (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2019), that is, how chronotopic images are invoked and constructed in order to make legitimate points. Karimzad & Catedral's (Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018) work on the power associated with certain chronotopes and its manifestation in actors’ sociolinguistic patterns is a case in point here. In their study, they suggest that more powerful chronotopes are those that feed from more hegemonic and dominant large-scale ideologies (e.g. monolingual and standard language ideologies vs. multilingual and superdiverse ones), and are thus more accessible. Therefore, given the argumentative nature of chronotopes and the salience of notions of ‘access’ and ‘accessibility’ in the discussions of power and chronotopes, and since social media has become a platform for voicing different sociocultural and political arguments, examining online interaction through a chronotopic-scalar approach offers us useful insight about the nature of, and power dynamics in, online communication.

What my study contributes to this line of scholarship is a chronotopic analysis of sociolinguistic normativity in the online-offline nexus, and the emerging forms of power in the era of internet and social media. I show how online and offline chronotopes of normalcy are in dialogue with each other when evaluating and sanctioning orthographic norms. Moreover, focusing on the argumentative nature of the performed chronotopic work, I highlight the importance of closely examining the creative processes of authority-claiming in online interactions hence further complexifying discussions of chronotopes and power (cf. Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018).

SOCIAL MEDIA AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF NEW ORTHOGRAPHIC NORMS IN IRAN

The internet penetration rate in Iran has been significantly and continuously on the rise over the last decade, and especially since the Green Movement in 2008 with users most active on three online spheres: blogospheres, social networking sites (SNS), and news and information platforms (Honari Reference Honari2015). Among the SNS, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are the most popular. Specifically, Twitter, a platform blocked by the government but used by many including numerous government officials, has been claimed to be ‘popular among journalists, young activists and campaigners and the Iranian diaspora’ (Honari Reference Honari2015:11). In addition, my ethnographic observation suggests that, in recent years, Twitter has gained more popularity among the young generation inside Iran. While the studies on Iranian Twitter have almost exclusively focused on explicitly political issues (e.g. Tabatabaei & Asadpour Reference Tabatabaei, Asadpour, Missaoui and Sarr2014; Wojcieszak & Smith Reference Wojcieszak and Smith2014), an area that merits a closer investigation is the users’ sociolinguistic patterns and positionings, especially with a focus on orthography due to its ideological loadedness (Sebba Reference Sebba1998). With the rise of online communication, and especially on SNS, a variety of new orthographic practices have emerged, among which are: Finglish (writing Farsi words with Roman alphabet), reversed Finglish (writing English words with Farsi alphabet), abbreviations (e.g. خخخ /xxx/ to mean ‘lol’; or the letter ج for جواب which means ‘answer’, etc.), inconsistent violations of standard spelling (i.e. spelling ‘mistakes’), and consistent patterns of violation of standard orthographic rules. ‘Hekasreh’, the focus of this article, is a particular instance of this last practice.

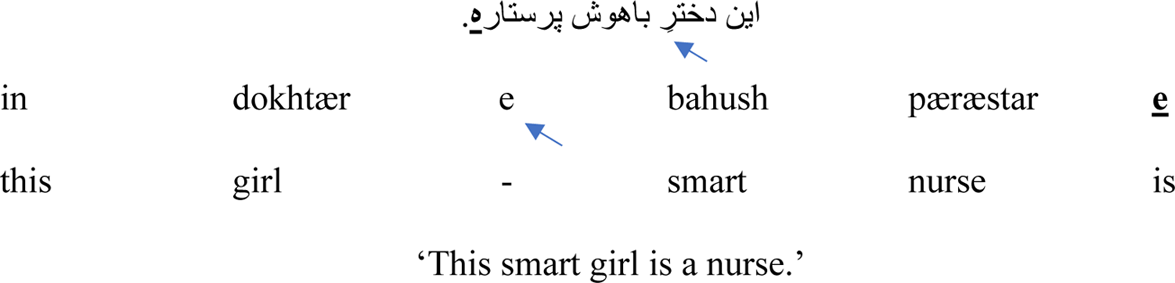

Farsi or Persian, the only official language in Iran, follows a modified version of Arabic script. The alphabet is written from right to left and consists of thirty-two characters that represent consonants and long vowels. The short vowels (/æ/, /e/, and /o/) in most cases, for example if not word-final and not representing certain free morphemes, are represented through diacritics, rather than alphabetic letters, that are often left out in everyday written communication (Baluch Reference Baluch, Malatesha Joshi and Aaron2006). ‘Hekasreh’ revolves around two orthographic rules related to the short vowel /e/. In standard Farsi orthography, there are two cases in which the sound /e/ is represented in two different ways and fulfills two different grammatical functions: (i) where /e/ is shown through the connecting letter /ە/ to represent the spoken form of the verb ‘to be’ in third person singular (‘is’), and (ii) where it is represented through the diacritic called ‘kasreh’ shown as ‘ؚ ’ (a short slant line that is put below letters) used in EzafeFootnote 1 construction. Application of these two rules can be seen in example (1) where the two cases of /e/ (‘is’ and Ezafe) are shown through an underline and an arrow respectively. Note that Farsi is written from right to left.

(1)

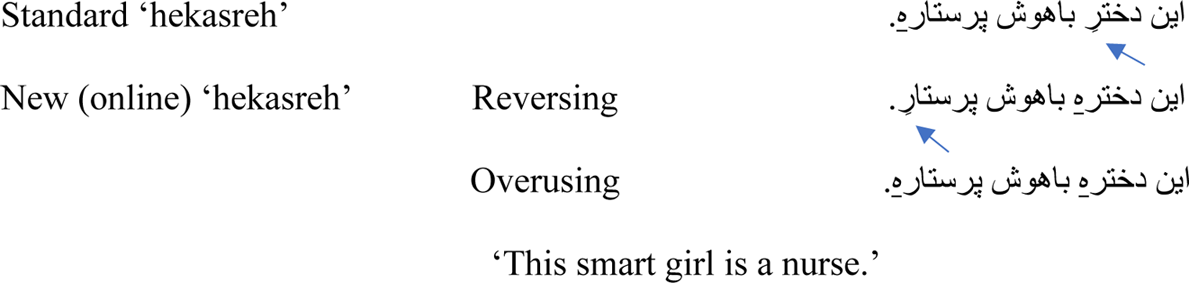

These two rules are in complementary distribution. In recent years, however, users on social media have started to consistently deviate from the standard rule in their online written texts, either reversing/swapping the two rules or overusing the first rule (i.e. using the letter /ە/ to represent both ‘is’ and Ezafe). Example (2) shows the different possibilities of ‘hekasreh’ use.

(2)

The emergence of the nonstandard ‘hekasreh’ has sparked debates on social media, especially Twitter, which are tagged by a variety of hashtags, the most trending of which is #هکسره (i.e. #hekasreh pronounced as /hekæsre/). This hashtag was first used on April 6, 2016 in a tweet criticizing the innovation. It is worth mentioning that while there had been continuous debates regarding this innovative orthographic practice very early on after its emergence, ‘hekasreh’ has been receiving a recent extreme attention as a result of its seeping into the offline platforms (e.g. commercial billboards, National Television's subtitles, etc.). This online-offline dialogue provides ever more reasons to closely examine this new norm and the attitudes and positionings toward it in order to gain an insight into online/offline sociolinguistic normativity.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS PROCEDURE

The data come from a larger ethnographic study on the online and offline sociolinguistic practices of Iranian communities both in the context of Iran and in diaspora. Following online and offline ethnography (Hymes Reference Hymes1996; Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2006) and using discourse analytic techniques, the data were collected and analyzed. The online data were gathered through systematic and nonparticipatory observation of Iranian Twitter users’ linguistic patterns starting May 2016 until March 2019. During this period, a dataset of 2,000 unique (re)tweets publicly posted and tagged with #هکسره (i.e. #hekasreh) was collected. Among these, 300 tweets were selected to be examined more closely as they represented the general alignment/disalignment patterns with regard to ‘hekasreh’ observed across the larger dataset. Two types of data were targets for examination in the study: (i) the tweeters’ metapragmatic commentary and (ii) their discursive/semiotic practices (e.g. different orthographic practices, (dis)alignment patterns, deictics, images posted, etc.). While the former was examined to unveil tweeters’ polycentric orientations and the specific chronotopes invoked in their evaluations of orthographic normalcy, the latter was focused on to see how these orientations would manifest in their actual practices.

Before moving on to the data and analysis, it should be pointed out that due to the government blocking of Twitter, users inside Iran can access Twitter only through anti-filter VPN services that hide their IP address and/or show a different location (e.g. European countries) for them. This, therefore, makes it almost impossible to know the location of the tweeters with certainty even through obtaining IP addresses from data analytics services. However, based on my online and offline ethnographic observation, and also as observed in the content of a large number of the tweets (e.g. posted images of instances of the new nonstandard ‘hekasreh’ on local billboards, public signs, local products, National TV programs, local celebrities’ social media, etc.), it appears that much of the ‘hekasreh’ discussion is taking place inside Iran.

POLYNORMATIVITY AND THE NEGOTIATION OF AUTHORITY IN THE ONLINE-OFFLINE NEXUS

In this section, I present data from the tweets collected around the ‘hekasreh’ debate along with a detailed analysis of each tweet. While the number of examples I focus on here to present certain patterns is limited, they are representative of the tweets in the larger dataset. Specifically, the nine tweets that I focus on were selected, after rounds of data revisiting, as they each portray the different patterns of chronotopic work that was done by tweeters regarding ‘hekasreh’ and hence together create an insightful understanding of the dynamics of the interactions. Through Figures 1 through 6, I demonstrate the tweeters’ positionings towards, and evaluations of, ‘hekasreh’ focusing on their orientations to different centers and invocation of differently scaled chronotopes. I further elaborate on the argumentative nature of the invoked chronotopes in Figures 7 through 13 illustrating the power dynamics in ‘hekasreh’ Twitter debates. Finally, I discuss the findings and implications for the sociolinguistics of online and offline interaction.

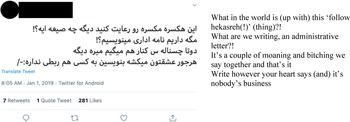

Figure 1. Tweet 1.

Policing ‘hekasreh’ and ‘bad Iranians’

Three different tweets posted by different tweeters are presented in this section. The common theme among the three pieces of data is users’ orientation to traditional centers of authority such as literature, nationalism, or standard language ideologies—chronotopes of tradition (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2015)—in their evaluation of new ‘hekasreh’ and its followers. Throughout the analysis, I trace the emergence of an idealized iconic image (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000, Reference Irvine, Gal and Duranti2009; Agha Reference Agha2005), the ‘good Iranian’, which the users who police ‘hekasreh’ construct through their chronotopic work and use as a lens to illegitimize the practices and identities of the followers of the new ‘hekasreh’. The first tweet to consider is presented in Figure 1. In this tweet #هکسره refers to the prescribed standard rule itself.

Tweeter1 appears to be reacting to someone's tweet/comment/post about Hafez and his poetry in which the user had violated standard ‘hekasreh’. What is being invoked is a literary figure, a poet from the distant past.Footnote 2 Hafez symbolizes a particular figure of personhood (Agha Reference Agha2005) situated in the time-space of Traditional Iran that is associated with authenticity and correctness. The tweet is written in the imperative form which illustrates how Tweeter1 distances him/herself from the new-‘hekasreh’-follower and in fact takes an authoritative position, especially that the structure has a singular ‘you’ conjugation, which, combined with the overall tone of the tweet, is read as condescending. Through this imperative (‘First, follow the #hekasreh (rule)…’), Tweeter1 implies that not following the standard ‘hekasreh’ disqualifies this specific person from commenting on Hafez's poetry.

This type of invocation of tradition through invoking different classical poets was very common across the dataset. They all revealed a similar pattern: the majority of them were reactions to other users’ reciting of, or comments on, these poets’ poetry while following nonstandard ‘hekasreh’ in their tweets. In many such reaction tweets, this authenticity and correctness brought about by the invocation of classical poetry would become entangled with nationalistic discourses together creating an iconic image of a ‘good Iranian’ as someone who knows Farsi literature and follows standard orthographic rules, ‘hekasreh’ included. Particularly, numerous tweets would invoke Ferdowsi, the tenth-century Iranian poet who is very closely associated with nationalist discourses and the ‘purification’ of Farsi (see Kia Reference Kia1998). One user, for instance, had tweeted: ‘Follow the #hekasreh (standard rule) for now, no need (for you) to congratulate Ferdowsi's commemoration day’.Footnote 3 Note the parallel discursive structure of this and Tweet 1 (and later Tweet 2). These examples show how tweeters who violate the standard ‘hekasreh’ get portrayed as deviating from the constructed image of the ‘good Iranian’ and as people whose comments on Farsi literature are illegitimate.

Tweet 1 also reveals further complexity as we see a mismatch between the metapragmatic commentary and the tweeter's actual linguistic/orthographic practices. One such mismatch is Tweeter1's crude, even obscene, word choice (‘cunt’ and ‘pimp’) while s/he orients toward a center of authority (i.e. literature) that is closely linked with the notion of tradition and properness. The second, more interesting, mismatch is his/her deviation from a certain standard orthographic practice: while standard ‘hekasreh’ is being followed, s/he is violating another orthographic practice by deliberately using a nonstandard spelling for the word ‘cunt’ (writing کص instead of کس both pronounced as /kos/). This is interesting because #کص has recently been a trending hashtag on social media. This new way of writing this word in Farsi might have originally started to bypass the filters and censorship around the search for sexual and taboo words on the internet from inside Iran. It has also more recently been used by social media users to index less impoliteness and less obscenity while using the word. In other words, by changing the last letter of the word to a different letter that represents the same sound (/s/), users have resisted filtering and also made it more ‘normal’ to use this previously obscene word online. Thus, we see Tweeter1's simultaneous orientation to traditional centers of authority as well as centers of resistance. That is, even in Tweeter1's perception, not all nonstandard orthographic norms are invalid as is evident in his/her intentional misspelling of the word ‘cunt’. S/he is in fact using a specifically online practice (writing کص ) and seems to be orienting away from traditional centers that s/he just invoked. What differentiates this from the case of ‘hekasreh’, however, is that the understanding of the pragmatic and metapragmatic function of orthography in this case is not solely linguistic, as is the case with ‘hekasreh’, but sociopolitical: resisting the top-down filtering practice in terms of both content and language. Therefore, what norms and the act of ‘deviating from norms’ imply is changed based on the context or is, in other words, chronotopic.

While Tweet 1 and other similar examples bring in traditional Farsi literature and connect that to nationalist discourses and the ‘hekasreh’, some others, like Tweet 2, draw more directly on national identity and its perceived connection to standard Farsi through specific hegemonic ideologies. In the following example, the iconic image of the ‘good Iranian’ is created by invoking the Persian Gulf, which is connected to strong nationalist and patriotic sentiments. We also see how this sense of patriotism gets linked to concerns about preserving the Farsi language. In Figure 2 (Tweet 2), #هکسره refers to the violation of the standard rule which is seen in the image posted by another tweeter and retweeted here by Tweeter2.

Figure 2. Tweet 2.

Tweeter2, like Tweeter1, is using an imperative and directly addressing the new-‘hekasreh’-follower taking an authoritative position. The imperative here is more forceful, however, due to the use of the emphatic pronoun (you (plural), شما pronounced as /ʃomɑ/) and its mismatch in number-agreement with the verb (don't destroy (sing.) داغون نکن pronounced as /dɑqun nækon/) that adds an extra layer of differentiation. This structure is not an uncommon one in Farsi, and its most common function is to create distance. Besides the distance, s/he illegitimizes the ethnolinguistic identity of the tweeter whose posted image s/he has retweeted. Tweeter2 does this in two ways: First, in Tweet 2, not following the standard ‘hekasreh’ (shown both through the hashtag and through the image retweeted) is being equated with ‘destroying the Farsi language’. This is followed by the mention of The Persian Gulf addressing the message in the picture (‘The forever Persian (Gulf)’) and implicitly invoking the global disputes and patriotic sentiments around the name of the Persian Gulf. These global disputes revolve around the disagreement regarding the name of this body of water. Specifically, although this body is historically known as the Persian Gulf, in the 1960s and with the emergence of Arab nationalism, several Arab countries started adopting the name Arab Gulf or Arabian Gulf, which raised disputes between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula. Throughout the years, the disputes have become increasingly more contentious extending to, and having consequences in, the global scales (see Levinson Reference Levinson2011). Not surprisingly, Iranians express very strong patriotic sentiments over this global naming dispute which is evident in the image retweeted (‘The forever Persian (Gulf)’). Tweeter2, therefore, draws on the one-nation-one-language ideology by bringing in and making a connection between the (standard) Farsi language and the Persian Gulf, a symbol of national pride and identity. Through this invocation, s/he creates an iconic image of a ‘good nationalist Iranian’, one who follows standard ‘hekasreh’ and hence does not ‘destroy’ the language and additionally cares about the name of the Persian Gulf. Through this iconic image, then, Tweeter2 negatively evaluates the new-‘hekasreh’-follower and his/her practices disqualifying him/her from making patriotic statements.

There were many similar examples connecting following the standard ‘hekasreh’ directly and explicitly to ‘being Iranian’. One tweeter, for instance, had replied to another user, who had written a comment mockingly criticizing typical ‘Iranian’ behavior (‘any/every Iranian (is) a master of confidently giving uninformed advice’) but violating standard ‘hekasreh’ in his/her tweet. The reply was ‘But every/any Iranian has to know the #hekasreh (standard rule) :| ’, pointing to the tweeter's violation of standard ‘hekasreh’ and directly drawing a connection between ‘being an Iranian’ and following standard ‘hekasreh’. The negative evaluation is made salient especially through the straight-face emoticon (:|), which shows his/her irritated tone. Another tweeter had tweeted ‘(I) wish that these battles (over ‘hekasreh’) yield a result at least and Iran and Iranians don't see a trace of #hekasreh (ever) again’, invoking national identity. Perhaps the most salient of all was a user who had tweeted ‘An Iranian is one who follows #hekasreh’, putting following standard ‘hekasreh’ as the gateway for ‘being Iranian’ and discrediting the ‘Iranianness’ of those who do not. All of these examples show the construction of the iconic image of a ‘good Iranian’, pointing to how following standard Farsi orthography gets connected to ethnolinguistic and national identity through their chronotopic work.

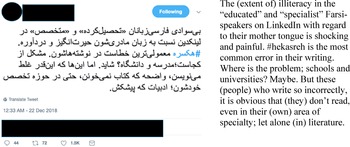

The last excerpt in this section provides us with a more specific scope, as we see that the iconic image gets more nuanced in Tweeter3's chronotopic work. The #هکسره in this tweet refers to the violation of standard ‘hekasreh’. In Figure 3 we see that Tweeter3, too, draws on one-nation-one-language ideologies through explicit reference to Farsi as ‘mother tongue’, associating the language with a sense of national belonging. Note that through this invocation s/he homogenizes all Iranians on Twitter as Farsi-speakers whose mother tongue is Farsi, erasing the multi-ethnic diversity of Iranians (see Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). S/he also later mentions literature, as a resource of national pride, which ‘Farsi-speakers’, especially ‘the “educated” and “specialist”’ ones, should know and read. The invocation of standard language ideologies in creating the iconic image is made even more explicit through his/her prescriptivist language (‘illiteracy’, ‘errors’, ‘incorrectly’) and mentioning of ‘schools and universities’, institutions that are the most influential in circulating and reproducing standardized norms, or to use Althusser's (Reference Althusser, Sharma and Gupta2006) terms the ideological state apparatus. However, s/he adds detail to the iconic image of a ‘good Iranian’, seen in the previous tweets, by making it more specific at a smaller scale rather than a broad and inclusive national one. This is done through the explicit word choice (‘the “educated” and “specialist” Farsi-speakers’) as well as situating the image in a particular online time-space frame that is associated with education and professionalism (‘LinkedIn’). Tweeter3, thus, adds fractal detail to the image and constructs a relatively higher resolution chronotopic image—that of a ‘good educated/professional Iranian’ (see Karimzad Reference Karimzad2021). S/he then evaluates ‘Farsi-speakers’ deviating from this image by not following standard orthography as illegitimate, ‘illiterate’, and even uneducated and inexpert Iranians (‘But these (people) who write so incorrectly, it is obvious that (they) don't read, even in their (own) area of specialty; let alone (in) literature’); note also the quotation marks around ‘educated’ and ‘specialist’ giving these words a mocking tone. In sum, through complex chronotopic-scalar orientations (i.e. large-scale offline chronotopes of tradition brought to dialogue with smaller-scale offline and online time-space frames of schools/universities and LinkedIn), Tweeter3 frames the orthographic ‘errors’ of a specific group of people (i.e. the so-called “educated” and “specialist”) on a specific online platform (‘LinkedIn’) as a ‘problem’, and a ‘shocking’ and ‘painful’ one nonetheless, illegitimizing the new-‘hekasreh’-followers’ practices and identities.

Figure 3. Tweet 3.

The tweets analyzed in this section illustrated the polycentricity of the users’ orientations and how they interact with their practices. While simultaneously orienting to different centers, the tweeters showed a general tendency to invoke large-scale offline chronotopes of tradition applying them directly to their appraisal of normalcy in online platforms. Tweet 3, specifically, showed a clear overlap of online and offline chronotopes by bringing them in dialogue with one another within the tweet. This online-offline overlap, then, reveals that no differentiation is made by these tweeters between online and offline contexts when evaluating normal sociolinguistic behavior, situating these practices in the online-offline nexus.

New ‘hekasreh’ followers and the online-offline differentiation

While the previous section focused on data from tweeters who would police ‘hekasreh’, here I present examples to illustrate how the new-‘hekasreh’-followers, too, construct an iconic image of the other group through their orientations towards more modern and transnational centers—what I refer to as chronotopes of modernity (cf. Dick Reference Dick2010; Koven Reference Koven2013)—and justify their positioning by portraying this image of the ‘hekasreh’ police and negatively evaluating them. Figure 4 shows one such tweet. The #هکسره refers here to the standard rule itself and following it.

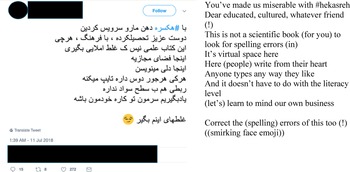

Figure 4. Tweet 4.

Right from the beginning, Tweeter4 creates distance from tweeters policing ‘hekasreh’ through directly addressing them and using deictic contrast (‘You’ve made us miserable with #hekasreh’). S/he then denaturalizes (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005) their so-called ‘educated’ and ‘cultured’ identities by sarcastically addressing them (‘Dear educated, cultured, whatever friend (!)’) implying that s/he does not consider their implicit authoritative claim about being ‘good educated Iranians’ themselves (and not others) as legitimate. Following this act of differentiation comes his/her situating his/her own, and other new-‘hekasreh’-followers’, online practices within a specific time-space frame: ‘This is not a scientific book (for you) to look for spelling errors (in). It's virtual space here. Here (people) write from their heart. Anyone types anyway they like’. Using the spatial deictic ‘here’ twice along with the deictic ‘This’, the tweeter highlights the spatiality of the specific sphere where these new practices occur (i.e. the online space). S/he also contrasts this aspect of online communication with an emblematic example of written text in offline spaces (‘This is not a scientific book’). In addition, by mentioning the word ‘type’, rather than ‘write’, s/he invokes the behaviors and activities specific to ‘virtual space’. Together through mentioning the specific spaces and the particular entities and activities associated with them, s/he expresses that his/her understanding of normal linguistic/orthographic practices is anchored in certain time-space frames of online and offline nature.

Furthermore, in his/her statement ‘it doesn't have to do with the literacy level’ s/he addresses the most common criticism directed at followers of new ‘hekasreh’: that they are illiterate. S/he makes this statement right after explicitly differentiating between the chronotopic organization of online and offline contexts and hence illegitimizes the traditional view of literacy, as was brought up in Tweets 1 through 3, and instead implicitly legitimizes a ‘new’ literacy, or rather literacies, that is, the online ones. S/he then takes an authoritative position through using authoritative language (‘(let's) learn to mind our own business’) and ends her tweet with an imperative which, combined with the smirking face emoji, seems to be jokingly daring the ‘hekasreh’ police audience to correct the instances of nonstandard orthography in his/her tweet. Through complex chronotopic work in the tweet, an image is created of the ‘hekasreh’ police the portrayal of which helps Tweeter4 in discrediting them. Through this iconic image, those who would police ‘hekasreh’ are portrayed as tech-naïve users who are constantly preoccupied with formalism and standardization and actively looking to correct other tweeters’ deviations from standard (‘This is not a scientific book (for you) to look for spelling errors (in)’ and ‘Correct the (spelling) errors of this too (!)’). This image of a tech-naïve pedant who is (only) interested in the minor details of formalism is one that is shown by Tweeter4 as ‘out of place’ and ‘not normal’ on an online platform (‘It's virtual space here, Here (people) write from their heart…’).

We observe that Tweeter4's orienting towards more transnational and global centers of ‘modernity’, and their situating in contrast to those of tradition, allow him/her to draw a clear contrast between online vs. offline chronotopes of normalcy. Unlike Tweets 1 through 3, here there seems to be no online-offline overlap. This is also seen in the tweeter's pointing to the out-of-placeness of the image created of the ‘hekasreh’ police. This online-offline differentiation pattern was observed in numerous examples. See for instance how Figure 5 shows another tweet that creates a chronotopic contrast by separating offline and online contexts. Note the similarity between the tone and the language in this tweet and Tweet 4.

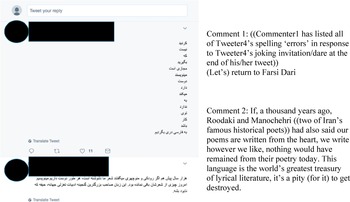

Figure 5. Tweet 5.

In this example we see, again, how this user creates distance at the beginning through voicing the ‘hekasreh’ police and questioning their message of ‘following hekasreh’. S/he too mentions an emblematic example of a written offline text (‘writing an administrative letter’) contrasting it with what is considered the usual type of Twitter communication. Finally, similar to Tweeter4, s/he invites other tweeters to write as their ‘heart says’ and points out that this is ‘nobody's business’. It is important to note that in the examples presented in this section as well, polycentricity is observed. That is, despite the clear online-offline divide in the tweeters’ metapragmatic commentary and their strong orientations away from traditional centers, a close examination of their actual practices reveals that they inconsistently violate standard ‘hekasreh’ and at the same time follow some other standard linguistic norms (e.g. in Tweet 4 writing ها pronounced as /hɑ/ rather than the shortened version of plural marker ا pronounced as /ɑ/ in غلطها meaning ‘errors’), pointing again to the importance of attending to online-offline nexus even if it is not explicitly notable.

I have so far demonstrated the chronotopic organization of Twitter users’ understandings of normal orthographic behavior. In the remainder of this section, I direct my focus to the argumentative nature of the chronotopic work done by the tweeters in their negotiations of normalcy. To this end, I delve deeper into the dialogic dynamics of the arguments by analyzing the comments posted under Tweet 4 shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Comments on Tweet 4.

Starting with the second comment, we see that Commenter2 implicitly illegitimizes Tweeter4's argument regarding the online-offline differentiation by invoking the image of two other literary figures (‘Roodaki and Manochehri’) living in a distant past (‘a thousand years ago’) in Iran, referring explicitly to a ‘traditional’ offline spatiotemporal configuration. S/he further draws a direct comparison between the social media users, as mentioned in Tweet4 (‘Here (people) write from their heart. Anyone types anyway they like’), and these historical literary figures making the counterargument that if these poets ‘had also said our poems are written from the heart, we write however we like, nothing would have remained from their poetry today’. In doing so, Commenter2 constructs a hypothetical scenario happening in an imagined ‘now’ (‘today’) where the new nonstandard online orthographic practices, that Tweeter4 is justifying as normal in ‘virtual space’, would have ‘destroyed’ Farsi, ‘the world's greatest treasury of lyrical literature’. Through this collapsing of time and space, Commenter2 reproduces norms that draw from large-scale chronotopes of tradition and applies them directly to online contexts. Similar to Tweeter3, then, Commenter2's response clearly points to the online-offline overlap mentioned earlier.

A noticeable point in the interaction between Tweeter4 and Commenter2 is that the latter has completely ignored the content of the argument made by Tweeter4 about the online-offline differentiation. This pattern of ‘dismissiveness’ can also be seen in the first comment: while Commenter1 has corrected all of the spelling ‘errors’ in Tweeter4's tweet, there is no discussion about the argument made in the tweet. Commenter1 has only written the list of the corrected forms of spelling and a short sentence at the end inviting to return to Farsi Dari, the more ‘authentic’ and ‘pure’ FarsiFootnote 4 in Commenter1's view. This total disregard of Tweeter4's somewhat lengthy argument demonstrates a power differential between the chronotopes of normalcy that different users are invoking and functioning within. This power differential stems from the difference in the ideological forces that feed into these chronotopes (Karimzad & Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018) as some users are drawing more from the hegemonic, hence more accessible, chronotopes of tradition while others are drawing from relatively less (locally) dominant chronotopes of modernity. These examples give us a glimpse into how chronotopes are invoked and utilized to make arguments and/or defend or refute them. My data have provided more empirical evidence for Karimzad & Catedral's (Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018) argument about the power differential between chronotopes that stems from the ideological power associated with different chronotopes. However, in line with my main goal in this article on delving deeper into the complex nature of online interaction, I show in the next section that understanding the dynamics of power and chronotopes, especially with the advances of technology and on online platforms, needs moving beyond the power ‘bestowed upon’ certain chronotopes by institutions, and paying attention to the processes through which chronotopic authorities are negotiated and claimed.

The internet and the new forms of power

In this section, I focus on how technology, specifically the internet, has provided opportunities for the emergence of new forms of power. I demonstrate that besides invoking more powerful, thus more accessible, chronotopes in the ‘hekasreh’ debate, users utilize a variety of affordances made possible by technology and internet culture to claim power in their argumentations. In the data presented, I explore how by creatively manipulating the accessibility of invoked chronotopes using different strategies, tweeters include some users and exclude others, exercising new forms of power. The first three pieces of data presented in Figures 7 through 9 help build my analysis for the final excerpt (Figure 11), which is the most indexically rich and perhaps the most exclusive. In Figure 7 below, #هکسره refers to standard ‘hekasreh’.

Figure 7. Tweet 6.

First off, Tweeter6 invokes chronotopic images of ‘war’ and ‘combatting’ by mentioning ‘fighting’ implicitly making the point that reminding other users to follow (standard) ‘hekasreh’ is like fighting a war. But the analogy does not stop there. S/he makes a direct comparison between fighting for ‘hekasreh’ and fighting وایت واکرا (the Persian transliterated form of the term ‘White Walkers’) claiming that the latter is easier. Through referencing the White Walkers, who are one of the critical anti-human characters of the popular HBO TV series Game of Thrones, Tweeter6, invokes images that operate at a global scale and are less dominant locally. In drawing on these less accessible chronotopic images, then, s/he restricts access to the different layers of meaning in his/her tweet and creates an in-group: only those users who are Game of Thrones fans or at least follow the show would get the reference and find the tweet funny. The user's message has been taken up by other users as can be observed through the number of ‘likes’ and ‘retweets’.

Another example illustrating the processes of insider/outsider selection through manipulation of accessibility can be seen in Figure 8 (boldface indicates a switch to English). In this tweet, access-restriction to the tweeter's argument about ‘hekasreh’ is done through switching to English. While all tweeters who read this tweet would know that it is about the ‘hekasreh’ debate through the hashtag, only people with proficiency in English, and particularly proficiency about certain English expressions (‘overrated’), would understand what the tweet means right away. Interestingly, another user has taken up the message and replied by posting a GIF of a scene from the Hollywood movie Mean Girls in the comments section disagreeing with the message conveyed in the tweet. This back and forth, again, reveals how exclusionary acts are performed based on the manipulation of the chronotopic images’ accessibility.

Figure 8. Tweet 7.

Another access-restricting strategy can be seen in Figure 9. The tweeter in this example has used an internet-specific device, that is, an internet meme, to make his/her point about ‘hekasreh’.

Figure 9. Tweet 8.

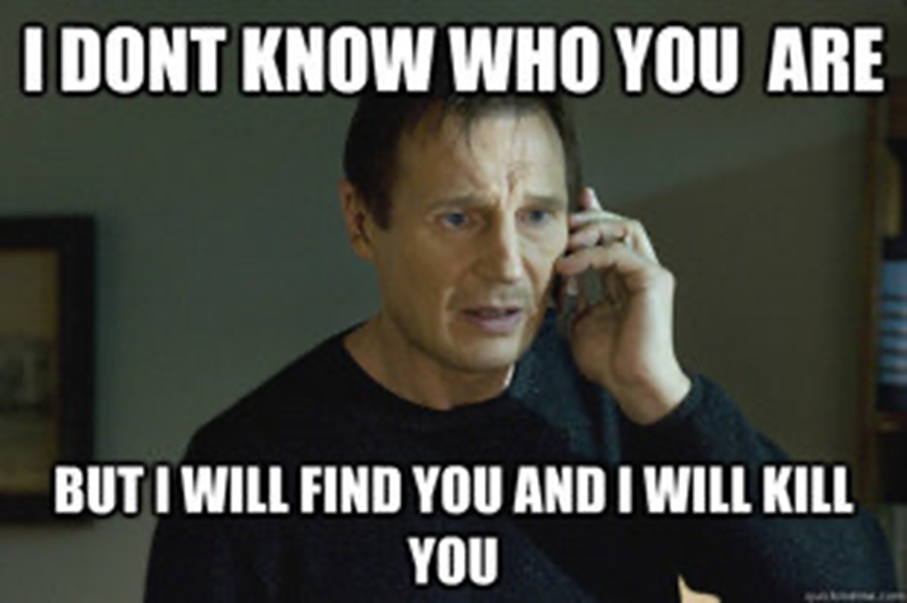

This tweet is an adaptation of one of the widely used internet memesFootnote 5 called the ‘Evil Kermit meme’.Footnote 6 This meme thread uses an image of the Muppet character, Kermit the Frog, talking to his nemesis dressed in Star Wars attire who tempts him to carry out some kind of irrational/unacceptable/abominable act. See an example of a typical Evil Kermit meme in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10. Evil Kermit meme.

Following the general theme of the Evil Kermit meme, Tweeter8 has portrayed the ‘hekasreh’ policing as an irrational, and even unacceptable, act one might be tempted to do. This is especially made salient through the exaggeration of the act (‘say “I'd even kill for it”’). S/he also denaturalizes the ‘distinguished’-ness of the ‘hekasreh’ police through the joke and hence criticizes them. The hashtag at the end (#havaei) is a Farsi expression among Iranian tweeters that they use when their tweet is directed at specific (group of) people but they want to avoid direct confrontation through replying or retweeting. Its use here shows that the ‘joke’ is a criticism directed at a certain group of people, that is, the ‘hekasreh’ police. We see here again how through using global chronotopic images and bringing them in the discussion of a local issue, Tweeter8 restricts accessibility to the entirety of his/her message so that only specific people (i.e. those who have seen this meme thread before and know how it is used and interpreted) would fully ‘get’ the message and find it funny creating an in-group.

The last example, shown below in Figure 11, is perhaps the most restrictive, in granting accessibility to its message, among the tweets examined in this section as it brings together all the mentioned exclusionary strategies in one tweet. The #هکسره in Figure 11 refers to the violation of the standard rule.

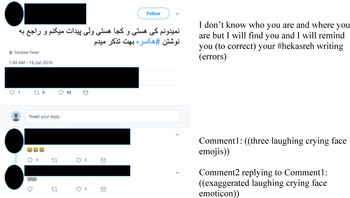

Figure 11. Tweet 9.

At first glance, there might seem to be nothing interesting about this tweet. However, the laughing face emojis in the comments do reveal that there may be other layers of meaning in the tweet that meet the eyes. In order to ‘get’ them, however, one has to have been exposed to a specific genre of Hollywood movies, and even beyond that a specific thread of internet memes. The tweet almost completely resembles a line from the thriller/action movie Taken released in 2009 starring Liam Neeson as Bryan Mills (Hoarau Reference Hoarau and Morel2008). The movie is about a former American government agent, Mills, whose daughter gets abducted by human traffickers and shows his struggles to track down and rescue his daughter. This specific line, whose almost identical Farsi translation is mentioned in this tweet, is from one of the critical scenes in the movie where Mills is talking to the abductor on the phone right after they had taken his daughter. The line goes:

I don't know who you are. I don't know what you want (…) If you let my daughter go now, that'll be the end of it. I will not look for you, I will not pursue you. But if you don't, I will look for you, I will find you, and I will kill you. (Hoarau Reference Hoarau and Morel2008)

The resemblance is notable when comparing the boldfaced sentences in the excerpt above with the translation of Tweet 9. What has been changed is that instead of ‘I will kill you’ at the end, we have ‘I will remind you (to correct) your #hekasreh writing (errors)’. This adoption and adaptation of the original message from the movie activates an archive of meanings at a global scale and bring those into dialogue with the ones at a local scale: the image of ‘hekasreh’ policing in Iran and in Farsi gets linked with the image of a rescue mission of a former American CIA agent, and in turn the violation of standard gets connected to a great crime like abduction that calls for action and retaliation. Through these cross-scalar and cross-chronotopic links, Tweeter9, similar to the other tweeters in this section, restricts access to the entirety of his/her message and hence creates an in-group of people who would, besides knowing that the tweet is about the ‘hekasreh’ debate, get the reference.

Moreover, there is yet another nuance to how the tweet is operating, which narrows down the potential in-group members even more. The tweet connects to a broader network of internet memes which use a screenshot from the movie with Mills on the phone and superimpose an English caption manipulating the original line to tailor it to a theme of threatening people about mundane everyday affairs that might annoy one. See examples of this in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Figure 12 is only the image and the caption without any manipulation, while Figure 13 is a typical example of the Taken memeFootnote 7 and closer to what we see in Tweet 9 here.

Figure 12. Taken meme 1.

Figure 13. Taken meme 2.

In this sense, then, Tweet 9 is functioning as a specific meme without an accompanying image, making its message even more implicit and restricting even further the in-group membership leading to the formation of tight-knit in-groups. The message of the tweet is received by the potential in-group members as we can see in the laughing comment on the tweet and the number of ‘likes’ and ‘retweets’.

The analysis of the data in this section demonstrates how tweeters use creativity to perform exclusionary acts and form tight-knit in-groups using a variety of technological affordances and communicative strategies (e.g. code-switching, references to pop culture and internet culture, etc.) and based on the limited accessibility of certain chronotopes. Therefore, adding to Karimzad & Catedral (Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018), I argue that while theorizing the argumentative nature and the power dynamics of chronotopes, one should pay heed not only to how the social actors invoke dominant and largely accessible chronotopes, that is, the so-called more powerful chronotopes, but also to how different forms of authority are claimed through performing exclusionary acts using processes of access restriction and strategically calling in less accessible chronotopes. I suggest that a chronotopic-scalar approach provides us with the tools to capture the complexities of these ‘outscaling’ power moves (see also Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010). Beyond the ‘hekasreh’ debate, this reveals how the New Media in the age of vernacular globalization has led to social actors’ increased agency both in the constructions of new normalcies and in the ways they argue for and justify their positionings with regard to these.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In this study, I have applied a chronotopic approach to the analysis of Iranian Twitter users’ understandings and evaluations of orthographic norms in online spaces by focusing on the specific case of ‘hekasreh’, a new Farsi orthographic norm. I presented data from the two general groups who argue for or against the new ‘hekasreh’ norm and examined their (simultaneous) orientations to different centers in their justifications, arguing for the chronotopic organization of their understandings of sociolinguistic normativity. Particularly, I demonstrated that the polycentric orientations of all users fall somewhere on a chronotopically organized spectrum that extends from a variety of differently scaled offline chronotopes (e.g. large-scale chronotopes of tradition and smaller scales time-space frames like universities and schools) to differently scaled online ones (e.g. large-scale chronotopes of modernity and smaller-scale time-space frames of LinkedIn or memes). As seen in the analysis, generally the orientations of those who disalign with the new ‘hekasreh’ would fall on a range of the spectrum that involves more larger-scale ‘traditional’ chronotopic images rooted in offline contexts. By contrast, those of the new-‘hekasreh’-followers can be situated within a domain of the spectrum that encompasses larger and smaller scale ‘modern’ images ingrained more in online contexts. I showed through closer examination, however, that a deep and comprehensive understanding of the interactions around ‘hekasreh’ goes beyond attending to these general tendencies and requires careful investigation of the intricate chronotopic work that is being carried out. I illustrated that this can be achieved through a chronotopic-scalar lens that allows us to explore how users situate the larger-scale chronotopes within smaller-scale ones (e.g. Tweet 3), adding to the chronotopic resolution of the images they invoke, or how they show simultaneous orientations towards differently scaled ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ images within online or offline time-space frames (e.g. Tweet 6).

The findings contribute to research on agency, power, and the sociolinguistics of normativity on social media in the era of vernacular globalization. I argue that technology and the internet have empowered users through providing them with devices and strategies that they agentively use to practice different forms of chronotopic authority. I specifically focused on the performance of exclusionary acts and creation of in-groups on the basis of the limited accessibility of certain chronotopes as ways through which users control who gains access to the entirety of the messages in their tweets. I, therefore, suggest that, besides considering the ideologically more powerful and accessible chronotopes, discussions of power and chronotopes should also take into account the creative processes of authority-claiming through different power moves in the dynamic interactions. The results of my study also provide more empirical evidence that shed light on the online-offline nexus. Through offering an account that takes into consideration the links across chronotopes and/or scales, I highlighted the dialogic nature of online and offline spaces. I specifically showed how users’ metapragmatic commentary and practices reveal simultaneous orientations to online and offline chronotopes and how in some cases (e.g. Tweets 1 through 3) the online and the offline largely overlap. This dynamic dialogue between online and offline spaces is in fact what leads to the constant updating of old normalcies and the emergence of new ones and has implications for the broader theories of sociolinguistics of online and offline communication drawing attention to their interaction. Finally, the study offers a clearer picture of the changing sociolinguistic scene in an understudied society by examining how globalization has impacted Iranians’ online/offline sociolinguistic behavior.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS