Each December, on a late afternoon a week or two before Christmas, dozens of U.S. Supreme Court staff members, clerks, and their guests sip drinks and indulge in an array of canapés and sweets in the court's Great Hall at the court's annual Christmas Recess Party. Many of the court's justices themselves also attend. The party has been an official tradition at the court since 1959, and although criticism surfaces annually about the persistence of the Christmas party in an institution that has long been viewed as a bulwark for religious freedom, the party goes on each year. Its signature event is the singing of Christmas carols in the East Conference Room, a handsome, wood-paneled room decorated with painted portraits of the court's early chief justices.Footnote 1 The caroling is accompanied by a pianist hired to play the grand piano that occupies the room, and traditionally the singing is led by the Chief Justice, although Chief Justices Rehnquist and Roberts often delegated the task to the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, who was exacting in his demands for perfect, four-part harmony.Footnote 2

The Supreme Court is obviously not a musical institution, and in many ways this annual caroling resembles the kind of communal singing that takes place in countless offices each holiday season. Nevertheless, a closer examination of the court and its internal traditions reveals that music has occupied a little-known and unusual place at the institution for decades. Previous scholarly work and popular accounts have explored music at the court, but they have largely documented individual justices’ musical interests and activities, such as the passion for opera that Justices Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg shared,Footnote 3 the court's use of song lyrics in its decisions,Footnote 4 and the court's decisions on matters of copyright, intellectual property, and the First Amendment.Footnote 5 Legal scholars and philosophers have also written about the similarities between legal argumentation and musical rhetoric, including how music can serve as a metaphor for understanding and articulating legal arguments and how both music and law are influenced by how their arguments are communicated.Footnote 6 Other past work has centered on the U.S. government as a patron of music, although the Supreme Court does not appear in that scholarship.Footnote 7

Although each of these research areas is important for understanding how music and the courts intersect and inform one another, this article focuses on a different kind of intersection: The performance of music at the U.S. Supreme Court through its little known, but long-running, concert series, Music at the Supreme Court. Music at the Supreme Court began as a single concert organized by Justice Harry Blackmun in May 1988. A frequent concertgoer, his interests in classical music had been highlighted publicly as early as 1974, when the Washington Post ran a feature about him that emphasized his fondness for chamber music. The article noted in particular how Blackmun enjoyed “strolling across the street from the court to the Library of Congress for its weekly concerts” as a way to “unwind.”Footnote 8 For Blackmun, concerts were not only a form of release, but also were a means for rejuvenating the mind. He frequently commented that the concerts at the Aspen Music Festival, which he attended every summer beginning in 1979, helped him to “re-charge his batteries” after a long year.Footnote 9 It was his hope that bringing music into the Supreme Court would serve a similar purpose for his colleagues and their staffs in the midst of the busiest part of the Supreme Court year, when the court had finished hearing cases and was fully immersed in the process of writing the dozens of opinions that would be issued before the end of each term in late June. As Blackmun explained in a 1995 interview with legal scholar Harold Koh:

I always felt that when the court got into late April and May and June, we were in a ten- or twelve-week period of great tension when nerves were taut and something ought to be done about that. So I tried to put the two together, bring a little music into the court to alleviate the tension…. It was a small intimate group and was not open to the public, and I think it afforded a couple of hours of diversion in the midst of what otherwise were very difficult hours.Footnote 10

Over its three-decade span, Music at the Supreme Court featured many of the leading names in American concert music.Footnote 11 Although the performances were officially “off the record,” details about them survive in a variety of primary sources, including the papers of former justices, records kept by the U.S. Supreme Court itself, the papers of friends of the court involved in the creation of these musical programs, and in interviews with individuals who supported and participated in the events. These sources, along with context from the contemporary press, have enabled a reconstruction of the history of Music at the Supreme Court and provide an opportunity to contextualize the concert series’ presence within the Court's culture and role in government. As the primary source materials reveal, the Music at the Supreme Court series began simply but developed over time into an elaborate enterprise encumbering public resources while also being supported by private sponsorship. The series allowed the court's justices to socialize with established and emerging musical artists, while simultaneously allowing Washington's elite musical patrons to hobnob with the justices themselves. For three decades, the court made use of public resources for the private benefit of the justices and their guests, and for nearly the first half of the series it tolerated (if not condoned) the use of the court's name to raise funds, including corporate donations, for the performances. The account of Music at the Supreme Court that follows thus provides a glimpse into the interpersonal relationships of the justices and their negotiations to make these concerts happen. It also illuminates the ways in which the concert series requires reckoning with how music and power interact at the nation's highest level.

The Supreme Court and Its Culture

The U.S. Supreme Court is the pinnacle of judicial power in the United States. A creation of Article III of the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court was planned by the framers in only the barest terms. Article III establishes the court and identifies the “cases and controversies” it must hear, but the Constitution leaves it to Congress to determine the number of justices, to set the court's appellate jurisdiction, and to create lower federal courts.Footnote 12 The court has had as few as six justices and as many as ten, although since 1869 the number of justices has been fixed at nine. The Constitution in Article II (which details the powers of the president) gives the task of confirming the president's nominations to the Supreme Court and all lower federal courts to the U.S. Senate, a process that has grown increasingly contentious over time.

The court is not only subject to the whims of Congress with regard to its composition and appellate jurisdiction. Congress also appropriates all funding for the federal judiciary, including for the Supreme Court; the budget is devoted nearly in its entirety to salaries for court personnel and to building maintenance.Footnote 13 Indeed, the Congress was the Supreme Court's landlord for the entire nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century; the court had no permanent building of its own and worked out of various spaces in the U.S. Capitol building until 1935, when construction of the Supreme Court building was completed. The funds to construct the building were appropriated by Congress only after then-Chief Justice (and former president) William Howard Taft successfully lobbied the legislature to provide a suitable building for its co-equal institutional partner.Footnote 14 The building itself is relatively small; its center section consists of Upper and Lower Great Halls and the courtroom itself. The remainder of the building houses chambers for the justices and their clerks, meeting rooms, a lawyer's lounge and office for the Solicitor General to use during court appearances, spaces for the Curator, Marshal, Counselor to the Chief Justice, and Public Information staffs, a Library, a cafeteria, and a gift shop. There is also a private justices’ dining room and conference room, and a small gym on the building's top floor. Notably, for the purposes of this study, there is no open, public space suitable for use as a performance hall, and the court has no catering kitchen or facilities to support large social gatherings, despite hosting such events from time to time.

Of the three branches, the Supreme Court is the least public-facing (save the confirmation process) and the institution is relentless in guarding its institutional integrity and impartiality. Although its building is open to the public, the U.S. Supreme Court is considerably less publicly accessible than the other branches of the U.S. national government. The U.S. Congress has televised its proceedings since 1979, and members of the public can visit their representatives with relative ease.Footnote 15 Presidents have long used their power to command media coverage to connect directly with the public and, as technology has increased, recent presidents and their staffs have used social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook to reach large swaths of the American public. In contrast, although the public can visit the Supreme Court and may even have the chance to sit in on oral argument, the court has resisted calls to televise its hearings, and the justices only rarely make public appearances. As an institution, the court is considered “small c” conservative; change comes slowly and deliberately, which is not surprising for an institution that relies heavily on precedent in its work. The turtles that hold up the lampposts in the building's courtyard symbolize the slow, deliberate pace of justice and of the court itself.Footnote 16

The Supreme Court's particular role in American government helps to sustain its relative privacy from the public, as does its institutional size. Compared with Congress or the president, the court's working community is much smaller than its counterparts, which lends itself to more intimate community events—like the Christmas party described earlier. Even when the justices find themselves on opposite sides of a legal question, they must engage respectfully with one another; after all, in an institution where the term of employment is in essence for the rest of one's life, there is every incentive to make friends.

The court has been the subject of innumerable studies of its institutional culture.Footnote 17 Its justices and decisions have also been well studied.Footnote 18 These studies have revealed an institution simultaneously central to American democracy and almost wholly removed from it. The institution sits atop a legal hierarchy consisting of multiple tiers of state and federal courts each populated by lawyers trained in a homogenized system of legal education that reinforces existing hierarchies and punishes nonconformity.Footnote 19 Access to the entirety of the court's facilities is reserved for the justices and their/the court's staff, with reduced access available to those admitted to the Supreme Court Bar and those with official business at the building, and substantially less access still to those members of the public that simply wish to visit the nation's highest court.

This brief background on the court and its culture illuminates two points that reinforce how unlikely it was that the court would come to serve as a musical performance venue. First, the court lacks the facilities, staff, and resources traditionally considered necessary to host concerts. Second, Congress's lack of funding to support such an endeavor illustrates how far afield it is from the court's official work. Nevertheless, despite these impediments, from 1988 to 2020, a musical series existed at the court.

Origins: A Birthday and a Piano

The court's justices have long commemorated special events and birthdays with one another. According to the late Justice John Paul Stevens, it was the late Chief Justice Warren Burger who started the tradition of the justices toasting and singing to whichever of their brethren was celebrating a birthday. Moreover it was just such an event that became the catalyst for the Music at the Supreme Court concert series.Footnote 20

In fall 1983, a gathering was planned at the court to celebrate Justice Harry Blackmun's 75th birthday. Blackmun loved music. He played a little piano, sang in the Harvard Glee Club as an undergraduate, and was a regular D.C. concertgoer; he wanted there to be music at his birthday party.Footnote 21 He decided to invite a young violinist, Robert McDuffie (b. 1958), whom he had previously heard perform at the Aspen Summer Music Festival and again at a private Washington, D.C. dinner party hosted by prominent D.C. insider Steven Strickland (1933–2015).Footnote 22 Blackmun and Strickland had known each other for a few years, dating back to Blackmun's participation in the Seminar on Justice and Society at the Aspen Institute, where Strickland served as the vice-president with responsibility for summer programming.Footnote 23 McDuffie, a recent Juilliard graduate, accepted Blackmun's invitation and made the trip from New York City with a classmate as his accompanist. McDuffie's performance at the Blackmun party was a resounding success, but it also revealed a problem: The poor state of the court's upright piano.Footnote 24 Called “hardly up to standard” in a Washington Post account, McDuffie later described the instrument in more candid terms: “It was the most despicable excuse for a piano that I have ever seen. I had to play softer so that the piano could be heard.”Footnote 25 Blackmun, too, recognized the sorry state of the court's upright and began to consider options for replacing it.

Replacing the piano proved to be no easy task. For one thing, pianos are expensive, and the Supreme Court's budget appropriation did not include discretionary funds for such a purchase. This meant that Blackmun would need to identify a donor willing to purchase the instrument. However that required Blackmun first to convince his colleagues of the necessity and propriety of accepting a donated piano. He began to explore options for acquiring a piano and presented two possible pathways to his colleagues at their conference—the twice weekly meeting of all the justices—of March 2, 1984.Footnote 26 His notes on that meeting indicate that both associate justices Sandra Day O'Connor and William Rehnquist (who would not become Chief Justice for 2 more years) were enthusiastic about the possibility of acquiring a new piano. However, Chief Justice Burger was “most lukewarm” about the proposed acquisition and indicated that he would need to think it over more carefully. Nothing more transpired about Blackmun's proposals for 2 weeks, until the conference of March 16, when Burger announced:

We do not need a piano. We already have one and it is adequate. Furthermore, we have no place for it. It would be difficult to move it around for there are “substantial problems” of handling the instrument. In addition, with all of the clamor about the court's overload, this would make bad publicity to announce that we had received a grand piano for entertainment purposes. After all, we use a piano only once a year, and the present instrument most adequately serves that purpose.Footnote 27

Burger's refusal to entertain Blackmun's proposal forced him to temporarily abandon it.Footnote 28 Two years later, however, in June 1986, Burger announced that he would retire and Rehnquist was appointed to the position of Chief Justice by President Ronald Reagan.Footnote 29 Rehnquist's new role allowed Blackmun to revisit the piano discussion. Rehnquist had been supportive of the court acquiring a new piano when Blackmun originally proposed to do so—and he himself was a dedicated patron of the arts.Footnote 30

As it turns out, even after Burger rejected the piano idea, Strickland had continued to pursue opportunities to locate a suitable instrument for the building. Recalling Blackmun's 1983 birthday party, Strickland later joked that he felt like Blackmun handpicked him for the job of finding a piano. He recalled: “At that party, Justice Blackmun said how the Supreme Court really needed a new piano, and he was looking right at me when he said it.”Footnote 31 Strickland had held leadership positions in government and non-profit organizations for over 30 years, and at that time he was president of the British Institute of the United States, a non-profit dedicated to preserving U.S.–British relations and history. In the fall of 1987, Strickland hit upon the idea of linking the purchase and dedication of a new piano to an upcoming British Institute symposium at the court to celebrate the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution and independent judiciary. Strickland thought the piano could be a gift from the British Institute to mark this important anniversary. The British Institute's board enthusiastically endorsed the idea and greenlighted Strickland to raise the necessary funds. With the board's blessing secured, Strickland contacted the Vice-President of the Baldwin Piano Company about selling the British Institute a piano at a greatly reduced price; once an agreement to do so had been secured, he sought funds to pay for the instrument. He approached members of the Board of Directors of the British Institute and his connections at the Dimick Foundation, a D.C.-area non-profit founded in 1957 that supports a range of arts-, youth-, and education-related activities in Washington, D.C., suburban Maryland, and Northern Virginia.Footnote 32 Strickland described this process in his opening remarks at the presentation of the piano to the court on May 20, 1988:

I called up the headquarters of the Baldwin Company, just outside of Cincinnati, and said that I had what was I thought was [sic] an interesting idea that I'd like to present to them and could I pay them a call the following week. … They thought the idea was terrific…They would be glad to be a partner in this project. I got back to Washington … and called an old friend and a new member of the Board of Directors of the British Institute, Mike Maloney, and arranged a meeting with him at his restaurant … and in another fifteen minutes, he had joined up. The next day I called a friend with the Dimick Foundation, and within 48 hours, I had word from its president, Joe Riley, that they would be a partner. So our project was assured.Footnote 33

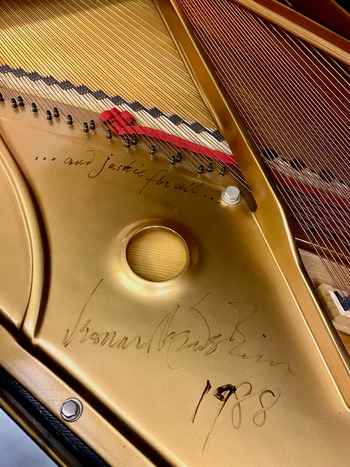

Strickland's agreement with the Baldwin Piano Company allowed the British Institute to acquire a 6′ 3″ Baldwin L for the court's East Conference Room at a cost of $6,998.00—roughly half the retail price.Footnote 34 Baldwin even agreed to have Leonard Bernstein select and sign the instrument in its New York showroom. Bernstein's inscription, “…and justice for all…” on the soundboard referenced the ideals enshrined in the Constitution and protected by the Supreme Court (Figure 1).Footnote 35

Figure 1. Inscription and plaque identifying the Baldwin piano donated to the U.S. Supreme Court by the British Institute, May 20, 1988. Photo by authors.

The piano secured, a special afternoon concert was planned at the court for May 20, 1988, to mark the dedication of the piano. Strickland, in consultation with Blackmun, was the principal planner of the event.Footnote 36 The May 20th dedication concert featured three solo artists as well as a chamber choir. McDuffie, as the original catalyst for acquiring the piano, was the anchor of the program. The other artists were singer/pianist Bobby Short, pianist Jon Kimura Parker, and a chamber choir conducted by Norman Scribner, founder of the D.C. Choral Arts Society. The program featured selections from the American songbook, as well as violin works by Kreisler, Saint-Saëns, and Gershwin, piano works by Chopin, Stravinsky, Joplin, Gershwin, and Tatum, and a new choral composition by Scribner on a John Dryden poem titled “A Song for St. Cecelia's Day.” Scribner scored his piece for nine singers (eight men and one woman) to reflect the composition of the court at that time.Footnote 37

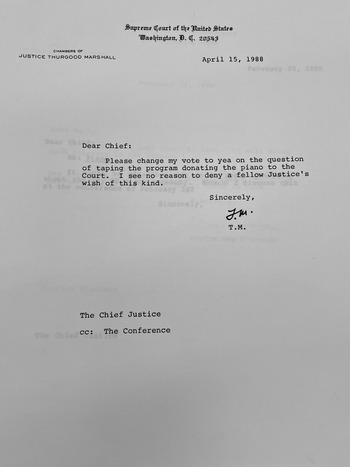

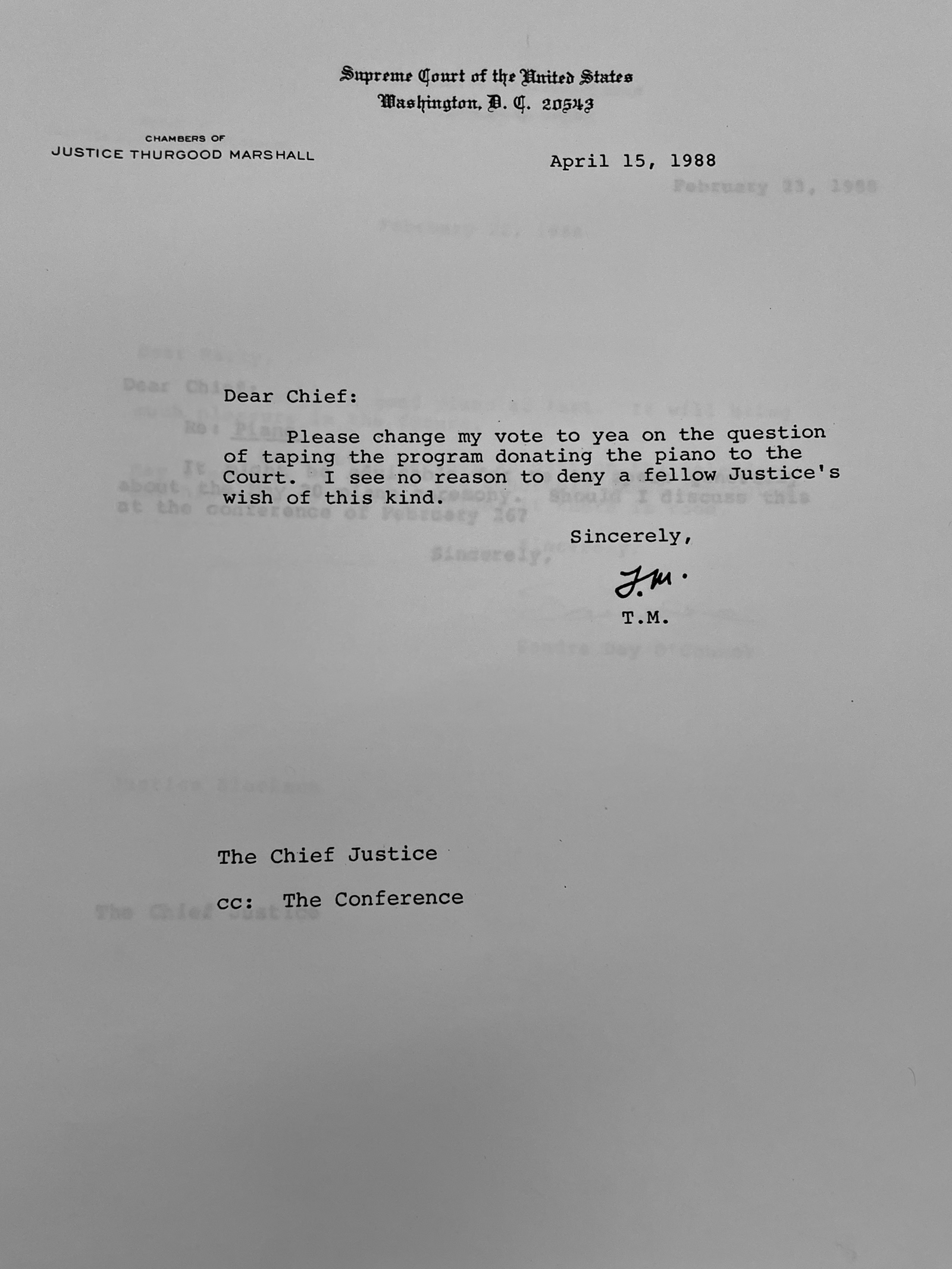

Strickland proposed that some portion of the concert could be recorded and aired on the National Public Radio (NPR) show Performance Today. Blackmun was fully in support of sharing the concert, but he first had to get his colleagues’ permission even to record the event. Blackmun later told McDuffie the vote on whether to allow a recording at all was five to four, with Justice Thurgood Marshall casting the deciding vote—an account confirmed by the correspondence between Marshall and Blackmun that is revealed in Figure 2.Footnote 38

Figure 2. Letter from Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall to Chief Justice William Rehnquist, April 15, 1988. Source: Blackmun Papers, Library of Congress. Photo by authors.

Recording the concert did not guarantee permission to broadcast it, however. In fact, the very likely possibility that the concert would not be broadcast meant that during the weeks leading up to the May 20 event, Blackmun, his staff, and other officers at the court fielded a number of requests for access to the performance. Among those to be accommodated were donors who had helped the British Institute pay for the piano, as well as members of the Supreme Court's credentialed press. On May 6, 1988, Blackmun responded to a request for performance seats for several prominent members of the court's press corps from Toni House, then the Public Information Officer at the court; in response, he explained that seating would be extremely limited due to the necessity of accommodating Strickland's guest list, which included the concert's “sponsors and donors.” He also noted that the concert was putting him in a difficult position because not all who wished to attend could be accommodated. He explained: “There will not be room for all the secretaries and all the law clerks and everyone else who works in the building. This is a matter of regret for me. … I am doing only the best I can.” This letter also acknowledged Blackmun's realization that the event was imposing a burden on the court and its personnel. He writes: “This whole business of May 20—despite the fact that I think it will be a sparkling program—is a touchy one for me for reasons I need not describe. I will sustain some scars.”Footnote 39

Regardless, by all accounts, the entire afternoon was a success. Eight of the nine justices were present, along with about 150 guests, many of whom had made some contribution to the cause of purchasing the piano. Ultimately, the court did agree to broadcast the concert following a request from Douglas Bennet, President of NPR, on June 8 that Blackmun forwarded to the Chief Justice for consideration on June 20; NPR music producer Benjamin Roe had been in attendance at the May 20th event. Four days later, Blackmun responded to Bennet to confirm that the court agreed that NPR could broadcast the concert or excerpts from it.Footnote 40 The concert aired on NPR in October 1988.

The dedication concert received significant media attention, as several members of the court's press corps had in fact made it onto the invitation list: Al Kamen from The Washington Post, Lyle Denniston from The Baltimore Sun, Steve Wermeil from The Wall Street Journal, and Dick Carelli from the Associated Press. Strickland's guest list added additional journalists: Warren Weaver from The New York Times, Tony Mauro from USA Today and Legal Times, and Paul Hume, The Washington Post's music editor.Footnote 41 On May 23, the piano dedication was the lead for Mauro's bi-monthly column about the Supreme Court in Legal Times. Footnote 42 Hume later presented a two-part commentary praising the event on his weekly radio program on WGMS.Footnote 43

Music at the Supreme Court: A Concert Becomes a Series

Both the private response within the court and the public attention to the 1988 dedication concert revealed that the performance of music at the court was broadly appealing within the circles of legal and political elites of which Blackmun and Strickland were a part. Nearly immediately, the two men began to think about doing it again, perhaps as a series. Blackmun and Strickland brought McDuffie into the conversation, and the three men hatched a plan for the Music at the Supreme Court concert series. Given the busy schedules of Blackmun, Strickland, and McDuffie (and that of the court), the three men initially determined that a biennial event made the most sense. In a Memorandum to the Supreme Court conference on February 8, 1990, Blackmun encouraged his brethren to save the date of Friday, May 11 for a second “musical ‘occasion.’”Footnote 44

The biennial schedule remained in place through 1996. In 1997 the “musicale” (as it came to be called internally) became an annual spring event. In 2007, the frequency increased again, to two concerts per term: One in November and one in May.Footnote 45 Initially, McDuffie and Blackmun took the lead on selecting the musicians for the concerts; by 1995, however, McDuffie's planning role concluded and suggestions of performers began to arise from Strickland and from the justices themselves.

From 1990 to 2002, Strickland headed up the necessary fundraising and was the “glue” that held the planning together.Footnote 46 Fundraising was essential because all the artists were paid a small, $1,000 stipend and travel expenses. Each concert also included a large reception at the court and a private dinner with the artists, hosted by one of the justices. These costs varied each year, but by 1999 Strickland had developed standard language for a fundraising letter that pegged the cost of the annual concert at approximately $15,000.Footnote 47 Records in Strickland's papers reveal that initially the funds for these concerts came primarily from donations by Strickland's personal friends and colleagues who were supporters of the D.C. music scene; they appear to have received invitations to attend the event at the court in exchange for their financial support. For example, in a 1999 fundraising solicitation, Strickland noted that Justice O'Connor would very soon be sending out invitations to that year's concert and then wrote: “Friends of Music at the Supreme Court…typically contribute $1000 toward the costs. If you do want to join us in this unusual enterprise, contributions should be made out to the National Peace Foundation and earmarked ‘Music at the Supreme Court.’ Contributions are tax deductible.”Footnote 48

Despite the attention the 1988 dedication concert garnered, once Music at the Supreme Court developed into a formal series, restrictions on press coverage were put in place. Blackmun himself referred to the concerts as occurring on a “semi-confidential basis and without publicity” in a memorandum to his colleagues in September 1995.Footnote 49 In November 2019, NPR's Nina Totenberg referenced that month's concert, but noted that the event was “officially off the record.”Footnote 50 Given the court's general reticence to share its private activities with the general public, no matter what the subject, the lack of media attention has also contributed to the lack of information available about the concert series. Excerpts of a few of the concerts were broadcast on Performance Today over the years, and occasionally a brief summary might appear in a news report about the court, but for the most part these concerts have remained a quiet feature of the inner community of the court, accessible only to those outsiders who contributed funds to support the performances, to those who had connections inside the court, and to those connected to the musicians themselves.Footnote 51 The original intent of the concert series as being for the court's personnel, the court's tendency toward circumspection, and the lack of any tradition of broadcasting the performances have suppressed awareness of the court's role as a venue for musical performance and, occasionally, even for world premieres of new works.

The Court as Concert Hall

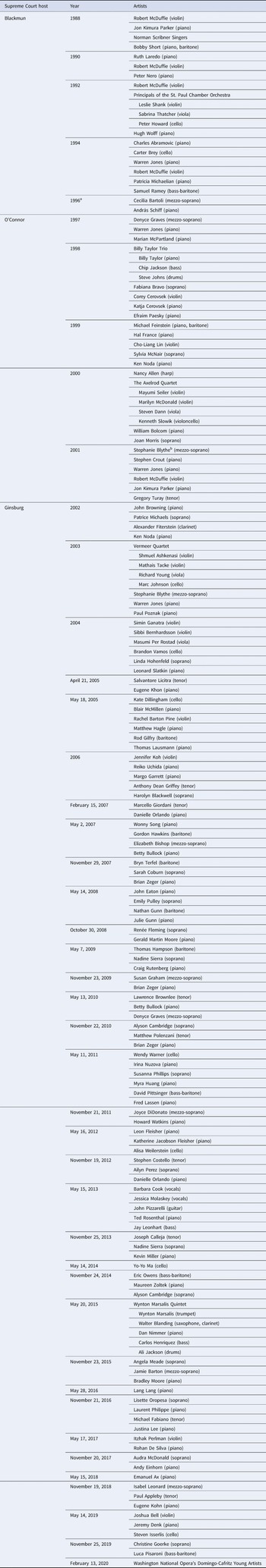

The list of musicians who have performed at the “musicale” over its 30-plus year history reveals that the programs included a mixture of emerging and well-known artists. The Appendix provides the most complete listing to date of artists who have appeared at the court between 1988 and 2020, and it includes some of the period's top musical performers. Both the Blackmun and Strickland papers—which carefully document the first seven concerts in the series (1988, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1997, 1998, 1999)—suggest that at least as far as the justices were concerned, the concerts were genuinely about the music and not solely about the personalities.

The archival evidence reveals the painstaking planning that surrounded each event and also shows that the concerts created complex challenges as the music series gained momentum. The Music at the Supreme Court concerts were not black tie affairs, nor were they scheduled for the evening or the weekends; nearly all took place mid-afternoon on a weekday. In that sense, the concerts operated on the model of the court's annual Christmas party; the logic was that, as the event was during the week, it would be possible for more employees to attend. The use of the term musicale by the justices to describe the events also suggested a less formal, more intimate, musical gathering. At the same time, the concerts did have some air of formality to them, not unlike any official event at the Supreme Court. Each concert included formal invitations, a catered reception following the event, printed programs, a carefully curated guest list, seating charts, and the necessary security measures. Moreover, the printed programs for the events did not use the term musicale but rather the more formal “Music at the Supreme Court.” Thus, the concerts were much more than informal or ad hoc musical gatherings.

Given the list of performers represented in the Appendix, an obvious question is: What music did the justices and their guests hear at these afternoon concerts? Because the events were off the record, reconstructing a precise catalog of the music performed over the life of the series is difficult. Luckily the first seven concerts are carefully documented in Blackmun and Strickland papers, and the Supreme Court itself has preserved copies of the programs for the later concerts. Those archival sources provide valuable information not only about the music performed but also the other factors that contributed to organizing the series at the court.

First, the programs were driven nearly entirely by the invited performers, whose own selection resulted initially from Strickland's first-hand knowledge of their work and later from suggestions by the justices themselves. Phone message records preserved in the Blackmun papers indicate that Strickland sometimes sought out Blackmun to “audition” artists he was considering; for example, a message from February 6, 1996 from Strickland to Blackmun invited Blackmun to Baltimore to hear Corey Cerovsek, “the next Bobby McDuffie,” on May 3. They did not go, but a March follow-up message invited Blackmun to a dinner at Strickland's home on May 7 to meet Cerovsek. Two years later, Cerovsek appeared on the 1998 Music at the Supreme Court program.Footnote 52 The Blackmun and Strickland files include no discussions among Blackmun, Strickland, or others involved in the planning process to indicate that anyone other than the artists themselves was involved in determining what the musicians should or should not perform. The invited musicians were free to choose whatever works they thought appropriate.

The records of those first seven concerts (1988, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1997, 1998, 1999) indicate that some common themes emerged.Footnote 53 First, the concerts highlighted music of the United States. Works by U.S. classical composers appeared on each of the first seven concerts, and in most instances dominated the respective programs. George Gershwin's music, in particular, was featured in nearly all of the programs, and works by Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Charles Ives also made appearances. In addition to these usual suspects in the U.S. art music repertoire, three of the first four concerts also included newly commissioned works by contemporary U.S. composers. The 1988 concert set the tone with Norman Scribner's new work for chamber choir and piano. At the next concert in 1990, U.S. composer Peter Lieberson (1946–2011) was commissioned to write a work in memory of Strickland's wife, Tamara Strickland, who had died tragically that year. Elegy was for violin and piano and premiered by McDuffie with Ruth Laredo accompanying. In 1994, a third new work was commissioned for the court, in this case in honor of Blackmun, who was retiring that year. The new piece, titled The Long Shadow of Lincoln, was by U.S. composer Stephen Paulus (1949–2014). Using the Carl Sandburg poem by the same name to form the basis of the lyrics, the Paulus work was written specifically for bass-baritone Samuel Ramey, who was among the featured performers presenting the world premiere at the 1994 concert. The funding for these three commissioned works was secured by Strickland, who negotiated with the composers under the aegis of the Friends of Music.Footnote 54

A second guiding principle in the Music at the Supreme Court series can also be discerned from that first decade of concerts, and it too supported the U.S. music theme. Five of the first seven concerts included a featured performer who specialized in U.S. music and whose repertoire focused on jazz or standards from Broadway musicals. In the 1988 program, U.S. cabaret singer and pianist Bobby Short filled that role. At the next concert in 1990, it was U.S. pianist and pops conductor Peter Nero. The 1992 and 1994 concerts veered slightly from this pattern, but in 1997 jazz pianist Marian McPartland anchored the program, and in the following 2 years, when the concert moved to an annual event, The Billy Taylor Trio and singer/pianist Michael Feinstein, respectively, appeared. The inclusion of performers who worked in genres other than classical concert music provided variety as well as spontaneity because each of the performers mentioned in this paragraph announced their programming choices from the stage. Even though the printed programs include no specific repertoire for these performers, it was clear that U.S. music was still at the forefront of what they offered. The playful blurb in the 1990 program for Peter Nero's portion of that concert provides a particularly vivid example: “Mr. Nero will announce his own program, which will probably include music of George Gershwin, possibly music of Cole Porter, and almost certainly music of other American composers as well.”Footnote 55

Thus, the programs at these concerts initially offered a balance of genres and moods. The overarching theme of music of the United States was not prescribed, but it is unsurprising given the historic setting of the East Conference Room, where artists performed under the watchful eyes of the portraits of chief justices past. Undoubtedly, the invitation to perform at the court was viewed as a tremendous honor by the performing musicians. As the president of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra noted when the SPCO's quintet was invited to perform in 1992, the invitation from the court carried great weight because it was a “national” venue, where musicians would perform for “the nation's leaders.”Footnote 56 It makes sense that the musicians would choose music that could honor or reflect on the United States and its music.

The extent to which the principles evident in the early concerts continued past 1999 is difficult to discern. The practice of commissioning new works seems to have quickly died away. No mentions of commissions appear in the files after 1994, perhaps because the added expense would have required additional fundraising. A longer view of the list of performers over the concert series’ 32-year span also shows some gradual shifts away from the series’ initial focus. The Blackmun years reveal a significant emphasis on instrumentalists, chamber music, and U.S. composers. After Blackmun handed off the series to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor in 1997, and continuing once O'Connor passed the baton to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2002, the emphasis on U.S. composers fades away, while performance by vocalists increases. In addition, during the Ginsburg years, the list of performers was increasingly populated by superstars, including Renée Fleming, Thomas Hampson, Joyce DiDonato, Yo-Yo Ma, Lang Lang, Itzhak Perlman, Emanuel Ax, and Wynton Marsalis. The increase in superstar performers coincides with Ginsburg taking the helm of the concert series and the end of Steven Strickland's role in producing the concerts. Strickland's intention to end his role once Ginsburg took over is documented in his correspondence with O'Connor about her decision to step away from the concert series. On May 4, 2001, Strickland wrote to O'Connor: “You have institutionalized the Music at the Supreme Court Series, which will make Justice Ginsburg's job easier. But the past five events that you presided over (and put together) have been so good that they will make her job harder. I will be glad to help as she gets underway, and then I will step back.”Footnote 57

The precise impact of the concerts on the working community of the Supreme Court is difficult to discern. The archival records show that the justices certainly valued the events, attended regularly, and warmly supported whichever of their colleagues was helping to spearhead the events. At the same time, the files also show the considerable investments of time and energy, largely by the court's staff members, that these concerts required. The Supreme Court was not a concert hall, nor were those organizing the events necessarily familiar with or capable of easily accommodating the kinds of logistics that musical events require. A 1992 memorandum from Wanda Martinson, Secretary to Justice Blackmun, to the Supreme Court Marshal's Office listed nine categories of arrangements that needed to be made for that year's performance, ranging from piano tuning, to configuring the Lawyer's Lounge as a green room, to reserving parking in the court's basement lot, to rearranging the East Conference room's furniture to accommodate the performance. Indeed, Martinson volunteered herself to help set up the chairs for the performance.Footnote 58 This extra work continued to be absorbed by the staff each year. Justice O'Connor's letter to the 2,000 participating artists noted that her staff were “available to do anything they can to make your visit as pleasant as possible.”Footnote 59

The musical artists themselves contributed to the logistical complexity of accommodating music-making at the court. A revealing early example happened during the planning for the 1990 concert; the first concert following the 1988 piano dedication program. Strickland wanted to secure a pianist to highlight the court's new piano and, with Robert McDuffie's help, they landed Ruth Laredo, who would perform solo, as well as accompany McDuffie in his selections. However to keep in line with the principle noted above of balancing the program between heavier and lighter fare, Strickland also secured Peter Nero for the event. In January 1990, Strickland happily reported to Blackmun that Nero had agreed.Footnote 60 Strickland later realized, however, when the specific details of the concert began to take shape, that Nero could not use the court's brand-new Baldwin grand piano. Nero was a Steinway artist and, per the terms of his contract, he would be bringing his own piano. Nero's people were quite nice about the matter and handled the added expense, delivery, and tuning, but the presence of a second piano created some spacing issues as well as another layer of logistical details to manage.Footnote 61

Strickland's papers also demonstrate that each of the justices he worked with devoted tremendous amounts of time, energy, and sometimes money to make the events possible. For example, in a 1994 memorandum to his colleagues, Blackmun indicated that he was involved with making the seating arrangements for the May 26 event, writing:

The musicale will take place in the East Conference Room at 3:00 p.m. on Thursday, May 26. If you wish, we can reserve seats for Justices and spouses; but assigned seating by seniority is complicated for those Justices who wish to sit with their guests. Unless I hear from you with a specific request, we shall assume you want to sit with your guests. Reserved seating cards will be placed on chairs in the front rows for you to claim on a first-come first-served basis.Footnote 62

The March 1996 musicale, which was to feature Cecilia Bartoli accompanied by András Schiff on the piano, provides another good example. Both artists’ careers were at their apex at the time, and the justices were abuzz in anticipation of this concert. Three weeks before the Bartoli musicale, following Bartoli's debut at the Metropolitan Opera, Justice Ginsburg wrote to Blackmun a handwritten note in excited anticipation: “Dear Harry, A thousand thanks to you and Dr. Strickland for arranging an afternoon that will lift our spirits sky high—Ruth.”Footnote 63 Yet the Blackmun papers also document the additional efforts that the visit by these artists required from him. The Blackmun papers show extensive discussions about selecting the proper day for the concert, so as to accommodate the greatest number of guests. As the concert drew near, the planning correspondence at the court shows that everyone was concerned about having enough seating.Footnote 64 Three days before the concert, Justice Scalia called Blackmun with “concerns about the noise from the lighting fixtures” in the conference room, fearing it would tarnish the event.Footnote 65 Unfortunately, Bartoli fell ill 2 days before the concert, and the entire event had to be cancelled.

As noted above, in 1997, Blackmun handed off the concert series to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.Footnote 66 O'Connor was a natural fit for the role as she was an early advocate for the acquisition of a piano, and, as is clear from the Strickland papers, she cherished the concerts and enjoyed brainstorming about musicians to invite. In March 1998, soon after she took over organizational responsibility from Blackmun, she wrote to Strickland enthusiastically suggesting soprano Sylvia McNair for a future concert, noting that she and Chief Justice Rehnquist had just heard McNair's “beautiful, clear voice” at a National Symphony concert two nights earlier and that it would be a “thrill” to hear her at the court.Footnote 67 McNair appeared at the court the following year. O'Connor's correspondence with Strickland also shows her pride in what their planning accomplished. After the 2000 concert, which she described as “enchanting” and “superb,” she wrote to Strickland, “we make a good team.”Footnote 68

The files show that while O'Connor took her responsibilities as host seriously she also welcomed input from others, in particular from her colleague, Justice Ginsburg, who was also known for her devotion to classical music, particularly opera. Ginsburg attended many musical performances in D.C. and would write to O'Connor after especially memorable ones, such as her note to O'Connor in June 2000 about tenor Gregory Turay's performance in the Washington Concert Opera's production of Bizet's Pearl Fishers. Ginsburg commented: “[He] captivated the audience. For me, it was a two-handkerchief performance.”Footnote 69 O'Connor took Ginsburg's advice about Turay, and he was on the following year's program. In February 2001, O'Connor handed off the concert series to Ginsburg, and she remained its chairperson until her death in 2020. Ginsburg considered it an event of utmost importance at the court.Footnote 70 The last musicale was held in February 2020; a month later, the coronavirus pandemic suspended all public programming at the court. As of the publication of this article, the concert series has not resumed.

The Intersections of Music, Money, Access, and Power

The Supreme Court's decades-long history of regular music performance is likely a surprise to many court watchers and musicologists, as the court has largely kept its musical events hidden—a reflection of both the court's penchant for secrecy and a self-conscious recognition that the performance of music by artists at the pinnacle of their careers for elite audiences at the highest court in the land might make for “bad publicity,” in the words of the late Chief Justice Warren Burger.Footnote 71 Nevertheless, there is little evidence of bad publicity, in no small part because the court's “regular” press corps was invited to each of the concerts but with the caveat that the events were “off-the-record, no photographs, etc.”Footnote 72 For example, at the concert in 1992, the Sun's Lyle Denniston, Nina Totenberg from National Public Radio, Linda Greenhouse from The New York Times, Ruth Marcus from The Washington Post, and Paul Barrett from The Wall Street Journal were on the official invitation list, as was Katharine Graham, owner and former publisher of The Washington Post.Footnote 73 By this point in time, however, restrictions on the press were firmly in place. In 1999, the Strickland papers reveal that the following reporters received invitations: The Associated Press’ Laurie Asseo and Dick Carelli, Lyle Denniston, Linda Greenhouse, Joan Biskupic from The Washington Post, David Pike from The Los Angeles Daily Journal, and National Public Radio's Nina Totenberg.Footnote 74 As with prior concerts, however, there is virtually no press about the event. Although it is outside the scope of the present study, the close relationship between the court and its press corps is apparent from the primary source materials in the Blackmun and Strickland papers, which raises its own important questions about the extent to which the Supreme Court press corps operates independently from the court itself.Footnote 75

The publicity issue is also intertwined with the issue that sparked Burger's initial reticence about acquiring a piano: The relevance of the instrument to the court's work and the propriety of the court holding musical events. In the early 1980s, the court's caseload was the subject of significant discussion, not only at the court but also in Congress. In his 1983 Annual Report on the State of the Judiciary, Burger noted that the court's workload had increased nearly fivefold from three decades earlier.Footnote 76 Burger initially rejected Blackmun's proposal to upgrade the court's piano because acquiring a piano and staging concerts would have undermined his argument that the court was overworked. Blackmun clearly had a different view with respect to overwork. He felt equally strongly that the tension associated with the court's growing workload was an argument in favor of the concerts.Footnote 77

Burger's retirement both preceded and was a necessary precondition for the establishment of the Music at the Supreme Court series, as a result there is nothing in the primary source materials to indicate how he would have responded to the outside fundraising necessary to make the concert series happen. Nevertheless, Burger understood how the appearance of the court at leisure would appear to outsiders—something that his brethren and sistren with ambitions to hear virtuoso performances in an intimate workplace setting were much less attuned to.

At the same time, the concerts do not simply raise questions of optics; they also raise genuine concerns about both the extraordinary access to the justices that the “Friends of Music at the Court” were afforded and the justices’ use of the court's facilities to satisfy their musical desires. Indeed, the commentary for Canon 2B of the Code of Conduct for United States Judges reads: “A judge should avoid lending the prestige of judicial office to advance the private interests of the judge or others.”Footnote 78 Although Supreme Court justices are not bound by the Code of Judicial Ethics, the concerts would be in conflict with this expectation, especially in the first decade of the concert series when Strickland was using the court's cachet to secure donations and recruit musical artists. In addition, the concerts, which demanded extraordinary time and effort from members of the Supreme Court staff, raise genuine concerns about the use of staff resources to host events with no connection to the court's official business. Both the Blackmun and the Strickland papers document the challenges for staff members of pulling off a concert series in a venue that was not designed for the performance of music. The Supreme Court building itself suffers from insufficient space and poor acoustics, and the court was not always well-equipped to meet the requirements of the artists themselves, as the Peter Nero Steinway matter in 1990 made clear. Moreover, the additional logistical burdens shouldered by the institution's very small staff had to be managed in the absence of budget resources to support the concerts.

Blackmun's retirement from the court and from spearheading the Music at the Supreme Court series, and the shift of responsibility to Justice O'Connor, did little to reduce the degree to which the court was actively involved in the management of the events. For example, a March 2000 letter to Strickland from O'Connor reported that she was having the court's Publications Unit prepare the programs for the 2000 event.Footnote 79 The Strickland papers also document correspondence with O'Connor about the selection of artists and the plan for each concert, as well as O'Connor's extensive correspondence with the artists themselves. The Strickland–O'Connor letters also reveal that the court was aware of the ways in which the fundraising activities for the now-annual concerts put the court in a difficult position. As noted previously, references to the “Friends of Music at the Supreme Court” appeared in the 1988 piano-dedication concert program, and the “Friends” and other sponsors were mentioned in each concert program thereafter through 1998. The programs cite not only individual contributors, but also support from such corporate and media supporters as Eli Lilly & Company, Chevy Chase Bank, Northwest Airlines, Black Entertainment Television, The Willard Hotel, West Publishing Company, U.S. West, and Pacific Telesis, among others.Footnote 80 It is not wholly apparent what each of these sponsors provided, but the archival materials indicate that Black Entertainment Television, Eli Lilly & Company, and Chevy Chase Bank were each contributing between $1000 and $2500 annually to support the concerts, whereas the Willard Hotel, the Jefferson Hotel, and the Swissotel Watergate Hotel (and presumably Northwest Airlines, as well) provided in-kind support for the musicians’ travel needs.Footnote 81

The solicitation and collection of funds from corporate and media donors, who were given access to the concerts and, thus, to the justices, was an unusual arrangement to say the least—indeed, even the British Institute's initial donation of the piano had raised eyebrows. In describing the inaugural concert, the story in The Washington Post noted that “one can't help but wonder why this was all done by the British Institute, whose stated purpose is ‘the enhancement of understanding of America's British heritage,’ and whose main activity is holding symposia on various legal subjects.”Footnote 82 The propriety of corporate sponsorship for these concerts must have been raised internally at the court at some point between 1998 and 1999; in a May 25, 1999 solicitation to recurring donors to Friends of Music at the Supreme Court, Strickland wrote:

As you no doubt noticed, there was no listing of “Friends” in the program this year. The court has become more sensitive than ever about “sponsorships” of anything related to its work or activities, especially corporate sponsorships. As you know we have usually had—fortunately—a few corporate contributions (typically of $2500); this year it was decided not to list those or the individual “Friends” who make our musicales possible.Footnote 83

However although the names of corporate and individual sponsors disappeared from the event programs from 1999 forward, Strickland does not appear to have been told to stop raising donations from corporate donors. Indeed, the Strickland papers reveal that in 1999 and 2000, both, Strickland returned to Eli Lilly & Company, Chevy Chase Bank, and Black Entertainment Television to ask them to renew their support.Footnote 84

It is impossible to say with certainty how the planning for the concerts proceeded after 2002, when Ginsburg took over hosting responsibilities. Strickland's papers do not record any substantive correspondence with Ginsburg, and Ginsburg's papers are not yet available. However, we know that the star power of the concerts during the Ginsburg years increased in part due to the partnerships she cultivated with the Washington, D.C. performing arts community. In 2003, Ginsburg reached out to Washington Performing Arts about assisting with the court's annual Spring musicale; later, after the Fall musicale was added in 2007, Ginsburg partnered with the Richard Tucker Music Foundation, an organization devoted to supporting young singers, to make the concerts happen.Footnote 85 The last concert held at the court in February 2020 featured young artists from the Washington National Opera's Domingo-Cafritz Young Artists program.

Conclusion: Music's Place at the Supreme Court

The three-decade history of the Supreme Court's musical events documented here reveals that the court has served as an unlikely yet persistent venue for showcasing the talents of both new and established musicians. That this is true is largely due to the tenacity of Justice Harry Blackmun, whose sincere interest in providing a musical respite for his colleagues led to the establishment of a long-running and successful concert series in the unlikely venue of the East Conference Room of the U.S. Supreme Court. Eventually, Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg shifted the content of the concerts away from emerging artists and chamber performances to more established performers and, especially during Ginsburg's years at the helm, to more emphasis on opera and vocal performance. Ginsburg's tenure as host in particular institutionalized the concert series and established it as a forum for superstar artists. The development and management of Music at the Supreme Court thus sheds light on the musical interests of these and other justices and provides insight into a set of cultural activities that have until now remained largely unknown in U.S. music history.

The story of the series also shines a light on the interesting role played by Stephen Strickland in producing and institutionalizing the concerts in ways that were to some extent at odds with the court's societal role. Strickland saw opportunities to leverage the court's exclusivity to attract prominent musical artists to appear. He also saw the opportunity to leverage the chance to hear high-caliber musical performances in the intimate setting of the Supreme Court's East Conference Room in order to raise funds from among D.C.'s arts elite to allow for the concerts. As Music at the Supreme Court was institutionalized, invitations to the concerts became more highly coveted, staff preparations became more painstaking and detailed, and questions arose inside the court about to whom to allow access. By the end of the series’ first decade, it is clear that there was some recognition of the problematic aspects of corporate sponsorship for the musicales. That did not put a stop to Strickland's corporate fundraising efforts, however, only to any public reference to them.

At the same time, it is also not clear to what extent the justices knew the methods of Strickland's fundraising or the specific details of the accounts. For example, the day after the 1994 event, which marked Blackmun's last musicale as a sitting justice, Associate Justice Lewis Powell sent him a note congratulating him on the event and adding: “I enclose my check for $100 as a contribution to ‘Music at the Supreme Court’. If you are personally paying for the entire program let me know.”Footnote 86 Even Justice O'Connor, who was intimately involved in the planning for the 1997–2001 concerts, seemed uncertain about the finances; in a May 12, 1999 letter to Strickland, O'Connor congratulated him on having put together a concert that was “the best yet,” then notes: “On a more mundane note, I spent $203.41 on wine and beverages for the reception. If you have sufficient contributions to cover it, you may refund it. Otherwise, please consider it my contribution.”Footnote 87

Still, the mere fact of the concerts themselves—which featured artists who appeared for far less (typically $1,000) than they could command for another performance and who appeared for a limited audience of social and journalistic elites—are a reminder of the ways in which the court and the justices exist within a cultural context far removed from the public the institution serves. Although the series began as an effort by Justice Blackmun to share the catharsis of his experiences at the Aspen Music Festival with his colleagues, Music at the Supreme Court became a complicated enterprise that entangled the court and its justices with corporate sponsors and outside patronage. That the justices were able to secure outside funding to enjoy the intimate performance of high-quality music with their friends and colleagues resulted entirely from the privileged positions they held. Viewed in its entirety, especially given the stature of musicians that appeared in its later years, the Music at the Supreme Court series raises questions about the propriety of the court lending its facilities and resources—and the justices lending their names—to this type of activity. It is perhaps worth noting that the congressional ethics committees prohibit members of Congress from benefitting personally from their legislative roles. The three institutions of American government (the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the U.S. Supreme Court) all also have historical societies—private, non-profit organizations that can be leveraged to allow the institutions to support activities outside their core functions. Indeed, the Supreme Court Historical Society was founded in 1974 and could certainly have been used to support the concert series, but for at least the first 15 years, the society was not involved.Footnote 88

It is unclear whether Music at the Supreme Court will resume now that the COVID-19 pandemic has abated. As noted previously, the last concert was held in 2020, just before the pandemic shuttered the court to public events and activities. The concerts’ most recent host, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the last in a long line of musically-inclined justices that included Abe Fortas, Harry Blackmun, William Rehnquist, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Antonin Scalia. With Ginsburg's death in September 2020, there is no obvious successor to carry on the concerts.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jim Eaglin, Robert McDuffie, Wanda Martinson, Elizabeth Killian, Kira Jones, Rhonda Evans, John D. Rackey, and several anonymous reviewers. Where uncited observations about the U.S. Supreme Court appear they reflect the first-hand observations of author Lauren Bell, who was a U.S. Supreme Court Fellow from August 2006 to August 2007.

Appendix: List of musicians appearing at the U.S. Supreme Court 1988–2020

James M. Doering is a professor of music and chair of the Department of Arts at Randolph-Macon College. His research in U.S. music has appeared in multiple journals, including American Music, Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, Musical Quarterly, and the Journal of the Society for American Music. His book, The Great Orchestrator (University of Illinois Press, 2013) about orchestra manager Arthur Judson was a recipient of an AMS-75 award.

Lauren C. Bell is the James L. Miller Professor of political science and special assistant to the provost at Randolph-Macon College. The author or co-author of several political science books, her solo- and co-authored work has also appeared in law reviews and peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Politics, Political Research Quarterly, The Journal of Legislative Studies, The Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Judicature, Social Science Quarterly, and The Wayne Law Review.