Introduction

Many theorists have found the notion of forgiveness to be paradoxical for it is thought that its appropriate application involves a deep tension. On the one hand, forgiveness could be appropriately directed at a person only if that person is blameworthy. On the other hand, if such a person is blameworthy, then it would seem that blame and not forgiveness is the proper response. Forgiveness, then, has been thought to involve ‘a kind of double vision’ (Calhoun Reference Calhoun1992: 82); it involves seeing the person as one toward whom blame both is and is not apt. Some have claimed that appeal to the notion of repentance can resolve this tension; repentance makes forgiveness appropriate (Murphy in Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988). But others have objected that such a response is explanatorily inadequate in the sense that it merely stipulates and names a solution but leaves the transformative power of repentance unexplained (Zaibert Reference Zaibert2009). Worse still, others have objected that such a response cannot succeed because no amount of repentance can render the blameworthy not blameworthy (Hallich Reference Hallich2013, Reference Hallich2016; Kekes Reference Kekes2009; Wallace Reference Wallace2019; Warmke and McKenna Reference Warmke, McKenna, Haji and Caouette2013). I argue that this latter objection is based on a mistaken assumption, the acknowledgement of which has the power to resolve the paradox in a way that meets the explanatory adequacy challenge and, more generally, has significant implications with which any full theory of forgiveness must engage. This will require, however, wading into the largely uncharted waters of the norms governing diachronic blame.

Let me begin by briefly identifying some assumptions I make about forgiveness and some related concepts. First, I assume that forgiveness is closely linked to blame, more specifically, its absence. Whatever else (full) forgiveness is, it necessarily involves the cessation of blame (see Allais Reference Allais2008: 33; Milam Reference Milam2018a; while I here assume that full forgiveness requires the cessation of blame, I also believe, as we will see, that partial forgiveness requires the reduction of blame). That is, I take it that blame and forgiveness are closely linked and yet importantly disanalogous. Blame and forgiveness are categorically distinct in the literal sense that they fall into distinct categories, for forgiveness involves an adjustment with respect to that with which blame is identified. For example, if blame is identified as an attitude, then forgiveness will consist in a particular kind of attitudinal adjustment (similarly, Kekes [Reference Kekes2009: 492] characterizes forgiveness as an event; contrast this with those, such as Gamlund [Reference Gamlund2010], who characterize forgiveness as itself a reactive attitude).

Second, I shall assume that blame is properly identified with an intentional attitude or range of such attitudes, the paradigm instance of which is resentment. This is an assumption made by many working on moral responsibility within the Strawsonian tradition (see Strawson Reference Strawson1962). When combined with the previous assumption, this yields the view that forgiveness typically involves the cessation of resentment. This view itself finds a home in work on forgiveness in the Butlerian tradition, which identifies forgiveness as the overcoming or foreswearing of resentment (see Butler [1726] Reference Butler and McNaughton2017: Sermons 8 and 9, and, for one influential example, Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988: 20). I emphasize that I assume only that resentment is a form of blame, leaving room for the possibility that other intentional attitudes are as well (such as disappointment, sadness, or dispassionate disapproval; see Richards [Reference Richards1988]; Kekes [Reference Kekes2009]; Portmore [Reference Portmore and Carlssonforthcoming]). I do assume, however, that all such blaming attitudes have a characteristic intentional content even if their affective texture differs. Thus, I assume that forgiveness involves the cessation of resentment or any other blaming attitudes though for ease of expression I shall speak simply of resentment and its cessation.

Third, I will appeal to the following general account of intentional attitudes and a particular sense of appropriateness that governs them. Intentional attitudes are attitudes that have intentional or representational content; they are about something, they represent their objects to be a certain way. And the attitude is appropriate, in this sense, to the extent that the representation is accurate. This is meant to capture the sense of appropriateness of an attitude that is referred to as fittingness and which I will also refer to as worthiness. It is a sense of appropriateness that is distinct from epistemic justification, prudence, and overall desirability. It concerns whether the attitude correctly represents the world in a way that is analogous to the relation between belief and truth. To illustrate, the attitude of fear represents its object to be dangerous in some way. The object is worthy of fear to the extent that the constituent representation is accurate, that is, to the extent that the object is actually dangerous. The object could be worthy of fear even if fear was inappropriate in some other sense. For example, a dangerous animal may be fear-worthy even if fear would be undesirable because the animal becomes more dangerous when it senses fear (Portmore Reference Portmore2019: 54). And while an attitude is appropriate in this sense in virtue of the accuracy of its constituent representation, an attitudinal adjustment may be appropriate, in the intended sense, when it involves making one's attitudes less unfitting. Thus, fourth, the worthiness of blame qua intentional attitude will be a matter of the fittingness of resentment, which itself is a matter of the accuracy of the intentional content of resentment. By extension, an adjustment in one's resentment will be appropriate, in the targeted sense, when it makes one's resentment less unfitting (see D'Arms and Jacobson Reference D'Arms and Jacobson2000; in the context of blame see Graham Reference Graham2014; Rosen Reference Rosen, Clarke, McKenna and Smith2015; Portmore Reference Portmore and Carlssonforthcoming; in the context of forgiveness see Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988: 29–30; Hieronymi Reference Hieronymi2001; Allais Reference Allais2008; Pettigrove Reference Pettigrove, McKenna, Nelkin and Warmke2021).Footnote 1

To summarize: I will treat (full) forgiveness as requiring the cessation of blame, blame as the attitude of resentment, resentment as an attitude with intentional content consisting in a representation of its object, and the worthiness of resentment as a matter of the accuracy of its constituent representation. The first two assumptions naturally accord with the common Butlerian claim that forgiveness involves the overcoming or forswearing of resentment. The latter two appeal to a common view of emotions qua intentional mental states. With this framework in mind, let us turn to the paradox of forgiveness.

1. The Paradox of Forgiveness, the Appeal to Repentance, and an Implicit Metaphysical Assumption

As I see it, the paradox of forgiveness most basically consists in the claim that appropriate forgiveness is logically impossible; forgiveness is never a fitting response. On the one hand, the appropriate target of forgiveness must be a blameworthy agent. One cannot, for example, appropriately forgive in virtue of acknowledging that the agent was not, after all, blameworthy. The cessation of blame, in such cases, would be due to the fact that one has come to accept that the agent had either an excuse or a justification. And this, clearly, does not amount to appropriate forgiveness because it does not amount to forgiveness at all. Appropriate forgiveness requires that the target be a blameworthy agent. On the other hand, if the target of appropriate forgiveness must be a blameworthy agent, then it seems to follow that the agent is worthy of blame, not its cessation. The paradox can be stated thusly:

(1) One can appropriately forgive only blameworthy agents.

(2) A blameworthy agent is appropriately blamed, not forgiven.

(3) Thus, one can appropriately forgive only those who are not appropriately forgiven.

(3) follows from (1) and (2), and yet both (1) and (2) appear to be quite plausible. It has been thought that if one were to reject (1), then forgiveness would have no point for forgiveness only makes sense in response to blameworthiness. The cessation of blame in the absence of blameworthiness, it seems, would have to be due to the fact that one has come to accept that the agent's act was either excused or justified. And if the act was excused or justified, then there would be nothing to forgive. On the other hand, it has been argued that a rejection of (2) would involve a failure to acknowledge properly that blameworthiness essentially involves the fittingness of condemnation. And a failure to condemn properly a transgression that merits such a response risks condoning it or not taking it sufficiently seriously in some way. Thus, the paradox of forgiveness claims that one can appropriately forgive only those who are not appropriately forgiven; forgiveness is never a fitting response (see Kolnai [Reference Kolnai1973–74: 99] who originally formulated the paradox as the claim that ‘forgiveness is either unjustified or pointless’, unjustified if directed at a blameworthy agent, pointless if not; see also Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988: 42; Hieronymi Reference Hieronymi2001; Allais Reference Allais2008; Kekes Reference Kekes2009; Zaibert Reference Zaibert2009; and Hallich Reference Hallich2013).

Faced with this tension, a number of theorists have emphasized the importance of repentance, defending the claim that forgiveness is appropriate when directed at the repentant. In direct response to the paradox, as formulated above, one may develop this response in one of two ways. One may, for example, argue that (1) is false because repentance can erase blameworthiness. Alternatively, one may reject (2) claiming that the repentantly blameworthy are not appropriately blamed. However the response is developed, why should we accept that repentance has this powerful transformative property? The most common answer appeals to the distancing between act and agent in which repentance consists. Jeffrie Murphy, for example, tells us:

[Repentance] is surely the clearest way in which a wrongdoer can sever himself from his past wrong. In having a sincere change of heart, he is withdrawing his endorsement from his own immoral past behavior; he is saying, “I no longer stand behind the wrongdoing, and I want to be separated from it. I stand with you in condemning it.” Of such a person it cannot be said that he is now conveying the message that he holds me in contempt. Thus I can relate to him now, through forgiveness, without fearing my own acquiescence in immorality or in judgments that I lack worth. I forgive him for what he now is. (Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988: 26)

On Murphy's view, wrong action sends an offensive or demeaning message to its victim. Repentance involves the withdrawal of this message, and it is this that makes forgiveness appropriate (for a related view see Hieronymi Reference Hieronymi2001). While there is surely something appealing about the idea that repentance can make forgiveness appropriate in this way, it has struck some as frustratingly vague. For example, Leo Zaibert (Reference Zaibert2009) finds the account explanatorily unsatisfying, variously referring to this transformative property of repentance as ‘alchemistic’ (377) and ‘quasi-magical’ (379). He explains:

Yet, the question as to what exactly this awesome power of repentance is remains unanswered. Unfortunately, the defenders of the forgiveness-requires-repentance thesis say precious little of help in answering this question. Merely to assert that repentance is communicative along the lines that these defenders sketch is not to explain why this communication has the effects that they claim it has. (380)

Thus, Zaibert holds that extant appeals to repentance are explanatorily wanting. As I read him, the objection is that the appeal to repentance merely names, by stipulation, a solution to the paradox. It does not, however, provide a developed and independently motivated one.

Brandon Warmke and Michael McKenna agree that the appeal to repentance requires a deeper explanation than what is so far on offer, and they claim further that there is a prima facie case against any such explanation:

One might think that forgiveness is appropriate when the wrongdoer has had a change of heart, apologized, requested forgiveness, and the like. Perhaps something like this is correct but, if so, some sort of explanation is called for. Engaging in these activities does not achieve exculpation—one can still be blameworthy even when one has had a change of heart, apologized, and asked for forgiveness. Breivik would remain morally blameworthy for his killings even had he immediately apologized and had a change of heart. So the puzzle remains: a wrongdoer remains blameworthy even after a change of heart, apology, etc. (Reference Warmke, McKenna, Haji and Caouette2013: 207)

Warmke and McKenna claim that the appeal to repentance cannot straightforwardly ease the tension of forgiveness because repentance cannot render a blameworthy agent not blameworthy (thus, they interpret the appeal to repentance as involving the first strategy of denying (1)). Wrongdoers, they tell us, remain blameworthy even after repentance. Why accept this claim? I believe that many theorists, frequently implicitly, take it to follow from more general metaphysical considerations relating to the fixity of the past and the numerical identity of persons. Occasionally, these background assumptions come to the forefront. For example, consider John Kekes:

But Straight blamed Bent for causing him undeserved, unjustified, and non-trivial harm, and nothing Bent could conceivably do after having done that could change what he did. Future events cannot change past events. If Straight's blame was reasonable before Bent's repentance, then it remains reasonable after it as well. . . . No amount of repentance by Bent could alter the fact that he got Straight fired in order to get the promotion. That is what makes it reasonable for Straight to blame Bent. (Reference Kekes2009: 502)

In a similar vein, R. Jay Wallace writes:

This familiar syndrome of ex post reactions to wrongful behavior [e.g., remorse, apology, making amends, resolving to do better] on the part of the agent of the behavior does not undo the wrong that they originally visited on the other party, and so it remains fitting for that party to resent the agent on that account. (Reference Wallace2019: 546)

And finally and most explicitly, Oliver Hallich:

Occasionally, we even talk of a remorseful wrongdoer's “moral rebirth” and seem to assume that sincere repentance causes a rupture in personal identity over time. . . . First, our talk of “moral rebirth” cannot be taken literally. The remorseful rapist does not, because he is remorseful, cease to be the person who committed the rape. He is still numerically identical with the wrongdoer. . . . The past cannot be undone, and if what you have done in the past is something that deserves moral blame and resentment, it does so irrespective of the fact that you may later come to feel remorse and repentance. . . . Brutal as it is, the truth is that good deeds cannot eliminate moral guilt since the wrongdoer, even after redressing the harm, is still numerically identical with the person who brought a moral wrong into the world. (Reference Hallich2016: 1014–16)

What these authors are claiming, I think, is that repentance does not have the power to falsify what they take to be an obvious metaphysical fact: that the blameworthy remain blameworthy. And though only Hallich is explicit about this, the claim that the blameworthy remain blameworthy implicates the notion of personal identity. For what is meant by this claim is that the blameworthy remain blameworthy for the remainder of their existence (e.g., even after repentance), and the duration of a person's existence is a matter of the correct criterion of personal identity. Though it may not be immediately obvious, this is how the claim that the blameworthy remain blameworthy involves the notion of personal identity. For it is to claim that if one is now personally identical with a past blameworthy agent, then one is now blameworthy. No amount of repentance could provide the relevant distancing between act and agent, short of a radical break in personal identity.

The metaphysical assumption implicit in the above objection can be made more explicit. But before that can be done, a distinction must first be introduced. The distinction is between synchronic blameworthiness and diachronic blameworthiness (and moral responsibility, more generally; see Khoury Reference Khoury2013; Matheson Reference Matheson2014; and Khoury and Matheson Reference Khoury and Matheson2018). Synchronic blameworthiness concerns the blameworthiness of an agent at the time of the action, while diachronic blameworthiness concerns the blameworthiness of an agent at some later time.

Exactly how the distinction is formulated will depend upon the underlying conception of time to which one appeals. Here, I will formulate these temporal claims on four-dimensionalism (see Sider Reference Sider2001). On this approach to persistence and change, the subject of an attribution of blameworthiness (or any other property that is had at or through time) is a temporal part of a whole, a time-slice. Thus, synchronic blameworthiness concerns an agent at t1's blameworthiness for an act that occurs at t1. And diachronic blameworthiness concerns an agent at t2's blameworthiness for an act at t1. But note that nothing in my argument requires the adoption of four-dimensionalism. One could instead adopt a three-dimensional relational view according to which the property of blameworthiness itself is a temporal relation (e.g., S is blameworthy at t for X) or opt for a number of other approaches depending on how one wishes to deal with the problem of temporary intrinsics (see Lewis Reference Lewis1986: 203–205; Sider Reference Sider2001: 92–98).

One simplifying feature of four-dimensionalism is that the relevant propositions are taken to be timelessly true, and thus this view avoids additional complexities arising from ‘taking tense seriously’, which involves the notion that propositions are true at times. Thus, if ‘[S at t1] is blameworthy for X’, then this is a timeless truth and can be truly asserted at any later time. However, if S does not exist at t3, then while ‘[S at t1] is blameworthy for X’ remains timelessly true and so can be truly asserted at t3, ‘[S at t3] is blameworthy for X’ is not true because [S at t3] fails to refer to an object that exists (these claims are easily conflated if one is not careful about these issues of formulation and background ontological assumptions). This follows uncontroversially from the general ontology. However, if ‘[S at t1] is blameworthy for X’, then, if [S at t2] exists, whether ‘[S at t2] is blameworthy for X’ is a substantive question concerning the nature of blameworthiness over time.

It is an assumption concerning this question that underlies the above rejection of the appeal to repentance. The assumption is that if one was blameworthy for an action at one point in one's life, then one will still be blameworthy for that action at all later points in one's life. This is to claim, if only implicitly, that personal identity is the diachronic ownership condition on blameworthiness and moral responsibility more generally. It is to claim that being personally identical with a past blameworthy agent itself suffices for diachronic blameworthiness. More precisely, if [A at t1] is blameworthy to degree d for committing act X at t1, then [B at t2] is blameworthy to degree d for X at t1 if [A at t1] and [B at t2] are stages of the same person.Footnote 2

According to this sufficiency claim, blameworthiness does not vary over time so long as personal identity holds. A commitment to this view is, I think, plausibly read off the above quotations from Warmke and McKenna (Reference Warmke, McKenna, Haji and Caouette2013: 207), Kekes (Reference Kekes2009: 502), Wallace (Reference Wallace2019: 546), and Hallich (Reference Hallich2016:1016; also see Kolnai Reference Kolnai1973–74: 101; Hallich Reference Hallich2013; and Richards Reference Richards1988: 87, among others). What these authors claim, if only implicitly, is that appeal to repentance cannot solve the paradox of forgiveness because repentance cannot diminish or extinguish blameworthiness because the repentant remain personally identical with the author of the blameworthy act. And even in an unrealistic thought experiment involving the severing of personal identity, it has been claimed that there is a residual paradox of forgiveness:

But even in a case like this a rupture in personal identity over time would not generate a duty to forgive. The reason why it would not is that if the repentant person were no longer identical with the wrongdoer, this would simply mean that the wrongdoer had ceased to exist. It would then be impossible to forgive him because the repentant person in front of us would be dissociated from the wrongdoer and there would no longer be an addressee for forgiveness. So there would be nobody to forgive and the question whether we ought to forgive could not arise. (Hallich Reference Hallich2013: 1007)

In sum, these authors believe that the appeal to repentance cannot solve the paradox of forgiveness because they believe, if only implicitly, that personal identity is the diachronic ownership condition on blameworthiness. But despite these implicit and explicit appeals to personal identity, Charles Griswold is hardly unique among forgiveness theorists in remarking that he ‘will not venture into the extremely difficult problems of personal identity’ (Reference Griswold2007: 50). Unfortunately, this is not something that we can avoid if we wish to properly understand the relation between forgiveness, repentance, and diachronic blameworthiness.

2. Personal Identity and the Nature of Diachronic Blameworthiness

I have argued at length elsewhere that personal identity is not the diachronic ownership condition on blameworthiness (see Khoury and Matheson Reference Khoury and Matheson2018; also see Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker2012; Khoury Reference Khoury2013; and Matheson Reference Matheson2014). Insofar as my interest here is in exploring the implications of this view for forgiveness, I will try to summarize the argument as briefly as I can.

However, the plausibility of the claim that personal identity is sufficient for diachronic blameworthiness cannot be adequately assessed in the absence of engagement with some of the details of the literature on personal identity. First, personal identity is a form of numerical identity. Numerical identity is a relation that holds between a thing and itself; it is an equivalence relation that is binary and transitive. It is binary in the sense that it is not scalar; it does not come in degrees. A and B are either numerically identical or not. And it is transitive in the familiar sense that if A is identical with B and B is identical with C, then A is identical with C. Because numerical identity has these logical properties, personal identity, qua form of numerical identity, will also have these logical properties.Footnote 3

In order to generate a criterion of personal identity that has the proper logic, the two leading accounts of personal identity both appeal to the notion of continuity. The biological approach, for example, holds that personal identity is a matter of continuity of vital biological function (see Olson Reference Olson1997). The psychological approach holds that personal identity is a matter of continuity of psychology (see Parfit Reference Parfit1984: 202–209). What is important for our purposes is that continuity of either of these sorts does not entail the persistence of any distinctive psychological content, where distinctive psychological content refers to the psychological properties that vary from person to person (see Parfit Reference Parfit1984: 300–301, 515n6, 517n17). This is obviously true with respect to the biological approach insofar as a person's vital biological functions can persist in the absence of any psychology whatsoever (as when in a persistent vegetative state).

But it is no less true with respect to the psychological approach. This view begins by appealing to the notion of a direct psychological connection. Historically, attention has been focused on the connections between memory and experience (Locke [1694] Reference Locke and Perry1975). An experience is directly psychologically connected to a memory when the experience causes the memory and the memory is of that experience. These two states are connected when they are bound by relations of causality and similarity. The same is true for other psychological states as well, such as beliefs and desires. A belief at an earlier time is directly connected to a belief at a later time when the former causes the latter and they have the same content. This is simply an account of the persistence of individual psychological states. Overall psychological connectedness between two points in time is a matter of the total number and strength of these individual direct connections between these two times. Connectedness, however, is a scalar relation; it comes in degrees. And so the defender of the psychological approach has some work to do to arrive at a criterion of identity with the appropriate logic. Appeal to the notion of strong psychological connectedness yields a non-scalar notion. Strong psychological connectedness is defined as the threshold of overall psychological connectedness that is itself necessary and sufficient for identity to hold day to day.Footnote 4 It thus yields a binary relation, for two person-stages are either strongly psychologically connected or not.

But although the notion of strong psychological connectedness is non-scalar, it is intransitive. You are strongly connected to your self yesterday, your self yesterday is strongly connected to your self the day before that, and so on. But you are not, I assume, strongly connected to your two-year-old self. Yet, you are personally identical with your two-year-old self. So the defender of the psychological approach has some additional work to do in order to yield a criterion that is also transitive. This is where appeal to the notion of continuity enters. Continuity, as a general matter, is the ancestral relation of some underlying relation. This means that continuity of a particular type holds between A and B when there are overlapping chains of some particular underlying relation between A and B. On the biological approach, this underlying relation will be some kind of biological connection. On the psychological approach the underlying relation is that of strong psychological connectedness. Though you are not strongly psychologically connected to your two-year-old self, there are overlapping chains of strong psychological connectedness between you now and your two-year-old self. Thus, you are psychologically continuous with your two-year-old self. We now have a psychological relation, namely, psychological continuity, that has the appropriate logic.

Importantly, ensuring that this psychological relation has the necessary logic to be a candidate criterion of the numerical identity of persons entails that this psychological relation implies nothing about one's distinctive psychology. This is not simply a buggy and dispensable feature of some particular account, but a consequence of securing the transitivity of identity in the face of change over time. Continuity consists in the holding of overlapping chains of some underlying relation. It can therefore hold over some duration in the absence of there being any direct link of that underlying relation over that duration. This, in turn, entails that psychological continuity is compatible with complete and total change in one's distinctive psychological features.

It is this implication that reveals the implausibility of the claim that personal identity is sufficient for diachronic blameworthiness. Both psychological and biological continuity can hold between a person at t1 and a person at t2 regardless of the content of their distinctive psychologies at those times. Thus, it is possible that a person who is a complete and total time-slice psychological twin of your preferred moral exemplar at t2 is psychologically and biologically continuous with a person who is a complete and total time-slice psychological twin of your preferred moral monster at t1. Hence, on the two leading accounts of personal identity, it is possible that the moral monster at t1 is personally identical with the moral exemplar at t2. The sufficiency claim thereby implies that in that case the moral exemplar is blameworthy for the actions of the moral monster, irrespective of what she is like at t2. This is, at least to my mind, an absurd result.

Presumably, the reason it is implausible to think that the moral exemplar at t2 is blameworthy for the action of the moral monster at t1 is that they do not resemble each other psychologically whatsoever. On the assumption that blame is the attitude of resentment and that resentment is an attitude that represents its object to be a certain way, then an object is worthy of resentment only if its constituent representation is accurate. I believe the intentional content of resentment involves the attribution of some defective psychological states to the subject that ground the particular kind of criticizability in which blameworthiness consists. In addition to providing what I think is the best explanation of the intuition that the exemplar at t2 is not blameworthy for the action of the monster at t1, this claim is also supported by phenomenal introspection. To resent another is, at least in part, to represent that other as being flawed in this way. The moral exemplar at t2, however, has no morally criticizable psychological states by stipulation. There is, then, no sense in which anyone could demand that the moral exemplar morally improve herself, and so it makes no sense to think that she is blameworthy.

If the foregoing is correct, then this provides a counterexample to the claim that personal identity is sufficient for diachronic blameworthiness. Personal identity holds in this case. The moral exemplar at t2 and the moral monster at t1 are stages of the same person, and yet the moral exemplar at t2 is not blameworthy for the actions of the moral monster at t1. Therefore, the sufficiency claim is false (for more extensive discussion see Khoury and Matheson Reference Khoury and Matheson2018).

This leaves us with the question of what it is that grounds diachronic blameworthiness, if not personal identity? Reflection on the above case in which a total lack of diachronic blameworthiness seems to be explained by a total lack of any direct psychological connections suggests that diachronic blameworthiness must consist in the presence of some direct psychological connections. Which direct psychological connections are the relevant ones? Various options are available. We may choose to set the bar relatively low, perhaps claiming that a single memory connection to a past synchronically blameworthy action suffices for diachronic blameworthiness. Or we may choose to set the bar higher, requiring some more robust set of psychological connections.

On my own view the relevant psychological connections concern the persistence of the criticizable psychological states expressed in the action (whatever those happen to be) in virtue of which the agent was synchronically blameworthy for the action (for the view that the properties that ground [synchronic] blameworthiness must themselves be psychological states of the agent see Khoury [Reference Khoury2018]; for the view that diachronic blameworthiness consists in the persistence of such states, see Khoury [Reference Khoury2013]; Khoury and Matheson Reference Khoury and Matheson2018). When there is maximal relevant psychological connectedness across time, which is to say that the criticizable psychological states persist undiminished, then there is no diminishment of blameworthiness across that time. When there is no relevant psychological connectedness across time whatsoever, then there is total diminishment of blameworthiness across that time. And when there is partial diminishment of relevant psychological connectedness across time, then there is partial diminishment of blameworthiness across that time. On this view, note, diachronic blameworthiness does not follow the logic of numerical identity. It can diminish and extinguish across time, which is to say that it is scalar and intransitive. This view, on which the property of blameworthiness can diminish and extinguish over time, may strike those caught in the grips of the sufficiency claim as puzzling. Be that as it may, let me emphasize that this view is no more metaphysically puzzling than the view that the property of being an insightful philosopher or a fast swimmer can also diminish and extinguish over time. Furthermore, there is a growing body of empirical research showing that folk judgments of deserved punishment and moral criticism for past wrongs are directly sensitive to judgments of psychological connectedness (see Tierney et al. Reference Tierney, Howard, Kumar, Kvaran, Nichols and Sytsma2014; Mott Reference Mott, Lombrozo, Knobe and Nichols2018).

It is worth noting that a given positive proposal of the relevant direct psychological connections is independent of the argument against the sufficiency claim. Thus, an objection to a particular positive account of the relevant sort of psychological connections is not itself an objection to the argument against the sufficiency claim. Despite this, let me end this section by briefly considering an objection, the response to which will hopefully lend plausibility to the general approach. The objection is that the view that diachronic blameworthiness consists in the persistence of the criticizable psychological states in virtue of which the agent is synchronically blameworthy makes it too easy to get off the hook. For instance, suppose that I commit a blameworthy action today. I am a fickle person, however, with fleeting psychological states, so tomorrow I wake up and no longer have the same psychological states in virtue of which I was previously blameworthy. Am I really claiming that a person could escape blameworthiness so easily?

The plausibility of this objection rests on assuming that the relevant psychological states are such that they could be eliminated rather rapidly and in a way that leaves the person relatively and relevantly unchanged. But this will not be feasible if we acknowledge (i) the holism of mental content and (ii) take the relevant psychological states to concern deep features of the agent such as her values and concerns. The holism of mental content says that our mental states make up a complex and interconnected web such that an alteration in one state will require updating any other states with which it is rationally connected (see Dennett Reference Dennett1978; Levy Reference Levy2007: 161–65). And one's values and concerns as expressed in action, facts about one's quality of will, I would say, are agentially deep partly in virtue of the fact that they have many such rational connections to other states (see Sripada Reference Sripada2016). Eliminating or dissolving one's deep values and concerns would require eliminating that in which they consist, a complex set of affective, volitional, and epistemic dispositions as well as any further states with which these are rationally connected. This is not a superficial change, and the resulting person would be very significantly different (a different moral self we might be inclined to say). Nor is this the sort of change that ordinarily occurs overnight.Footnote 5 More commonly such deep change is a long, slow, and often painful process just of the sort associated with genuine repentance.

3. Resolving the Paradox and Meeting the Explanatory Challenge

Let us return now to the paradox of forgiveness. Earlier, I formulated the paradox as follows:

(1) One can only appropriately forgive a blameworthy agent.

(2) A blameworthy agent is appropriately blamed, not forgiven.

(3) Thus, one can appropriately forgive only those who are not appropriately forgiven.

We are now in a position to see that the original formulation involves an equivocation. ‘A blameworthy agent’ as it is used in (1) minimally refers to an agent who was blameworthy at some point in the past, while its use in (2) refers to an agent who is blameworthy at that time. Thus, the claims can be clarified as:

-

(1′) One can only appropriately forgive an agent who was blameworthy.

-

(2′) An agent who is blameworthy is appropriately blamed, not forgiven.

(1′) still accounts for the idea that forgiveness makes sense only in response to blameworthiness. One can still distinguish forgiveness from excuse and justification on its basis. It simply says that the only candidates for appropriate forgiveness are those agents who were blameworthy for some faulty past conduct. And (2′) still makes sense of the idea that what the blameworthy are worthy of is blame, lest we condone the wrong action. But notice now that (3) no longer follows because we have acknowledged the possibility that though one was blameworthy, one may be now less or not blameworthy for that earlier conduct. One may lack blameworthiness for a past act not only because the act was excused or justified, as many assume, but also because the conditions of diachronic blameworthiness are less than maximally met. What I wish to emphasize at this point is simply that once we properly temporally index blameworthiness and acknowledge the possibility that diachronic blameworthiness can diminish and extinguish, the inference in the paradox of forgiveness is revealed to be invalid.

Before continuing, let me stress what I am not claiming. I do not claim that there is no other source of confusion underlying the appeal of the paradox. Some, for instance, argue that the paradox is due to an equivocation over different kinds of reasons or senses of appropriateness. For example, Hallich (Reference Hallich2013) argues that while there can never be moral reasons that make forgiveness morally mandatory, there can be prudential reasons as well as nonobligating moral reasons in favor of forgiveness. And Wallace (Reference Wallace2019), argues that while blame is always a fitting response to an agent who has done wrong, there may be nonfitting related reasons to critically manage such blame in a way that amounts to forgiveness. I have no dispute with the idea that the cessation of blame (in a way that may amount to forgiveness) may be supported by other considerations such as its therapeutic value and that this may give rise to some confusion. Both these authors, however, commit themselves to the claim that the paradox stands when we hold fixed the relevant sense of appropriateness as fittingness (or, for Hallich, moral reasons that make forgiveness morally mandatory). It is this claim that I dispute, particularly as it pertains to those who claim, if only implicitly, that the appeal to repentance cannot solve the paradox because the repentant remain personally identical with the wrongdoer (such as both Hallich and Wallace themselves).

Recall that defenders of repentance appeal to the claim that repentance can make forgiveness appropriate in virtue of the distancing that occurs between act and agent. Critics of repentance, we saw, claimed that the relevant distancing could not occur insofar as one was still personally identical with the author of the blameworthy act and thereby appealed to the sufficiency claim. But that claim is false. The sense of diachronic ownership that is relevant to blameworthiness does not concern personal identity, but concerns psychological connectedness of the relevant sort. This is the underlying but largely unarticulated insight of the appeal to repentance (though see Allais Reference Allais2008: 38).

Recall the passage by Murphy quoted earlier:

[Repentance] is surely the clearest way in which a wrongdoer can sever himself from his past wrong. In having a sincere change of heart, he is withdrawing his endorsement from his own immoral past behavior; he is saying, “I no longer stand behind the wrongdoing, and I want to be separated from it. I stand with you in condemning it.”. . . I forgive him for what he now is. (Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988: 26, my emphasis)

We can now see that the genuinely repentant are those who are, to some extent, relevantly psychologically disconnected from their earlier blameworthy action. Genuine repentance, it would seem, consists in the breaking of such psychological connections (Kolnai's own characterization of repentance is prescient: ‘repentance amounts to a loathing and dissolving of the very attitude that has underlain his bad action’ (Reference Kolnai1973–74: 106n2). And they are, for that reason, less or not at all blameworthy for the earlier blameworthy action. This is the needed explanation of the transformative power of repentance: genuine repentance makes forgiveness appropriate because it involves diminished diachronic blameworthiness.

Two points of clarification are in order. First, though repentance is one way of breaking the relevant connections, it is clearly not the only way. Repentance, presumably, requires that the relevant connections have been broken in a particular way, for example, because the person has sufficiently reckoned or wrestled with those problematic aspects of her character. Thus, I believe that genuine repentance is sufficient but not necessary for a reduction of diachronic blameworthiness. Second, I am inclined to call a reduction of blame in light of an awareness of reduced blameworthiness ‘forgiveness’. Hence, while I do claim, roughly, that repentance requires forgiveness, I do not claim that forgiveness requires repentance. My view is compatible with the possibility that a reduction of blame in the absence of genuine repentance may amount to forgiveness.

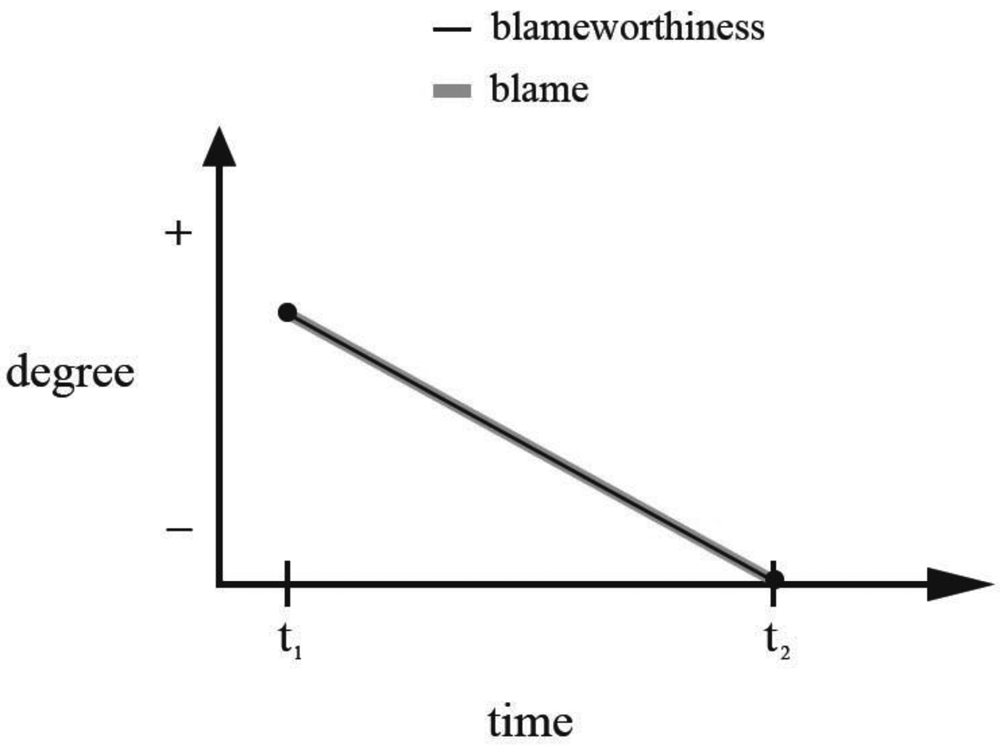

With this framework in mind, let us look at some examples. Consider figure 1:

Figure 1.

Figure 1 illustrates a case in which the agent's diachronic blameworthiness for some particular act remains stable between t1 and t2. And, in this case, the blamer's blame of the agent for that act perfectly tracks this fact, in the sense that the blamer blames the agent to the degree that she does because the agent is blameworthy to that degree. In this case it is clear that [the blamer at t2] has not forgiven [the agent at t2] for [the act at t1] and that this failure to forgive is perfectly appropriate.

Consider now figure 2:

Figure 2.

Figure 2 represents a case in which the agent's blameworthiness diminishes across time. Suppose too that, as in the case above, the blamer's blame of the agent perfectly tracks the blameworthiness facts. Has the blamer forgiven the agent? I am inclined to say that yes, [the blamer at t2] has fully forgiven [the agent at t2] for [the action at t1] though I recognize that this is far from a paradigm case.

Consider figure 3:

Figure 3.

The case represented in figure 3 is like that of figure 2 in that we have the same reduction of diachronic blameworthiness. But with respect to the actual blamer's blame of the agent between t1 and t2, figure 3 is like figure 1. The blamer stably blames the agent to a high degree between t1 and t2, and such blame becomes less and less fitting across that duration. Suppose that at t2 the agent makes sincere expressions of repentance to the blamer by way of apology. Suppose that the blamer accepts this as genuine and, in light of such an acceptance, no longer blames the agent. Has the blamer forgiven the agent at this time? I am inclined to say that, yes, [the blamer at t2] has fully forgiven [the agent at t2] for [the act at t1] and that such forgiveness is appropriate. Further, I am inclined to think that this is a paradigm case of fitting forgiveness.

This suggests, among other things, that there is a crucial epistemic element in our forgiveness practices. I tentatively suggest that forgiveness, qua distinctively recognizable phenomenon, arises in large part due to our epistemically limited nature. Forgiveness is most recognizable when there is relatively significant diachronic blame reduction over a relatively short duration (e.g., as in figure 3 in comparison to figure 2). And insofar as it is plausible, as I think it is, that reductions in diachronic blameworthiness are comparatively more gradual (because deep psychological change tends to be comparatively slower), then the most recognizable cases of forgiveness will occur in contexts of limited knowledge of the agent's diachronic blameworthiness. From this perspective, the ritual of repentance, apology, and forgiveness looks to be an occasion for reevaluating diachronic blameworthiness. Through the process of repentance diachronic blameworthiness can diminish, one can express this through apology, and a blamer can appropriately acknowledge and react to this through forgiveness.

Recall Hallich's (Reference Hallich2013: 1007) claim that in cases involving the severing of personal identity there is a residual paradox of forgiveness. According to this thought, either personal identity with the wrongdoer holds or it does not. If it does, then the wrongdoer remains fully blameworthy and so does not merit forgiveness. If it does not, then, because the person before us is not identical with the wrongdoer, there is no one to forgive. The mistake in this line of reasoning is in thinking that the relation that grounds diachronic blameworthiness either holds completely or not at all, as it would if that relation were personal identity. But consider the possibilities illustrated in figures 2 and 3 at any time between t1 and t2. In these cases there is a partial, but not total, diminishment of diachronic blameworthiness. In such cases a partial reduction of blame is fitting, and there is a clear target of such diachronic blame reduction. I am inclined to describe this as a case in which partial forgiveness is fitting.Footnote 6 Such cases, then, effectively fly between the horns of Hallich's dilemma. When it comes to diachronic blameworthiness, there is plenty of space between non-mitigation and total exculpation, and forgiveness helps us navigate this moral terrain. Arguably, this is the space of forgiveness as we most frequently encounter it.

4. Implications and Complications

Before closing I want to consider briefly some further implications and complications of the view I have begun to develop. The former are implications with which, if the argument of this paper is sound, all full theories of forgiveness must engage. The latter concern questions left open by this view.

The first implication is that on this view it is not the case that forgiveness is always elective, as a number of theorists claim (see, for example, Kolnai [Reference Kolnai1973–74: 101–102]; Sussman [Reference Sussman2005: 87]; Hallich [Reference Hallich2013, Reference Hallich2016: 1008–1009]; in thinking that forgiveness is not always elective, I am in agreement with Gamlund [Reference Gamlund2010] and Milam [Reference Milam2018b]). The diachronic blame reduction in which forgiveness (at least, partly) consists will be rationally required when the agent's diachronic blameworthiness has diminished or extinguished, and the potential forgiver knows this. In such a case, the potential forgiver does not have the rationally permissible option to continue to blame. To continue to blame would be to misrepresent what the agent is like, and the attitude would not be fitting for that reason.

This, in turn, implies that accounts that construe forgiveness as the exercise of a normative power are, at the least, more limited in scope than is commonly thought. On such accounts, forgiveness is thought to involve, roughly, releasing one from a debt or relinquishing one's right to blame. For example, Dana Nelkin writes:

In forgiving one ceases to hold the offense against the offender, and this in turn means releasing them from a special kind of personal obligation incurred as a result of committing the wrong act against one. . . . Forgiveness is distinct from excuse, because a release from a personal obligation has no implications for a change in attribution of responsibility for the act. (Reference Nelkin, Haji and Caouette2013: 175)

As Nelkin conceives it, forgiveness involves ceasing to hold the offense against the offender while, presumably, continuing to do so would still be fitting (because, she thinks, there is no change in responsibility). Relatedly, on Warmke's view, ‘In forgiving we relinquish certain rights (for example, to blame)’ (Reference Warmke2016: 690). Presumably, one has a right to blame a person to a degree, in the relevant sense, only if that person is blameworthy to (at least) that degree. Such accounts then are applicable only in cases in which it remains fitting to blame or otherwise hold the offense against the person. They are unable to explain, however, cases of the sort I have emphasized in which blame becomes less fitting over time. If, as I am inclined to think, we can felicitously describe diachronic blame reduction in light of an awareness of diminished diachronic blameworthiness as forgiveness, then forgiveness cannot be fully explained by such normative power accounts. Because these accounts construe forgiveness as the exercise of a power to relinquish fitting attitudes or responses, they only apply to elective forgiveness and not all forgiveness is elective.

A second implication of this view is that nothing is, in principle, unforgiveable (for different arguments to a similar conclusion see Govier [Reference Govier1999]; Griswold [Reference Griswold2007: 90–97]; Murphy [Reference Murphy2009]). No matter how synchronically blameworthy an agent is for some earlier action, if there are no relevant psychological connections at some later time, then the agent at the later time will not be diachronically blameworthy for the earlier act. This is akin to multiplication by zero; when there are no direct distinctive psychological connections between t1 and t2, it does not matter how blameworthy the agent was at t1 because the properties that ground such blameworthiness do not themselves persist through time.

A third implication is that forgiveness, in light of diminishing diachronic blameworthiness, is not at all in tension with self-respect or respect for morality. Many theorists have taken it as a significant challenge to explain why this is so (Kolnai Reference Kolnai1973–74; Murphy and Hampton Reference Murphy and Hampton1988; Hieronymi Reference Hieronymi2001; Allais Reference Allais2008). On the view developed here, this challenge is straightforwardly met. There is no tension because one may forgive [an agent at t2] while not forgiving [the agent at t1]. One may blame [the agent at those times at which the agent has the properties that ground blameworthiness], and one may not blame [the agent at those times at which she fails to have the properties that ground blameworthiness].When grounded in an acknowledgement of reduced diachronic blameworthiness, forgiveness is fully compatible with respect for oneself and for morality because such forgiveness does not require abandoning blame of those who are worthy of it.

Fourth, and for similar reasons, blame and forgiveness of the dead can be appropriate. This is because acknowledging that there is a temporal component to blameworthiness (the subject of blameworthiness as I have here formulated it) allows that there may be an asymmetry between the time at which one does or does not blame and, as it were, the time to which one does or does not blame. For instance, at t3 B at may come to truly believe that a long since dead person A did go through a deep and genuine process of repentance later in his life such that at t2, just prior to his death, his diachronic blameworthiness for an earlier act at t1 was eliminated. In this way, [B at t3] may cease to blame [A at t2] for [the act at t1], and this may amount to forgiveness of [A at t2], who is dead at t3, for [the act at t1].

So much for implications. The first complication, gestured to above, is that this account does not attempt to explain elective forgiveness. While I have claimed that not all forgiveness is elective, my account is compatible with the claim that some forgiveness is. Elective forgiveness is forgiveness in which continued and undiminished blame is fitting; that is, forgiveness of an agent at t who is blameworthy. Because I have been primarily interested in addressing the issue of whether forgiveness can be fitting, I have not engaged with the issue of whether the cessation of fitting blame can be appropriate in other senses and whether any of these amount to elective forgiveness (on these other senses see Hallich Reference Hallich2013; Wallace Reference Wallace2019). Some may see this issue as the primary question a theory of forgiveness should answer (for example, Calhoun Reference Calhoun1992; Allais Reference Allais2008: 39; Zaibert Reference Zaibert2009: 368; though see Fricker Reference Fricker2019 for an argument that elective forgiveness is parasitic on earned forgiveness). Perhaps that is true. I am content to emphasize that in the context of theorizing about forgiveness it is crucial to recognize that blameworthiness can diminish over time, and that when it does, continued blame, of the sort characteristic of a failure to forgive, is unfitting.

Lastly, while I have been concerned here with the implications of the possibility of diminishing blameworthiness for forgiveness, I want to briefly raise the possibility that blameworthiness may sometimes increase over time. Suppose that at t1 an agent commits a blameworthy action due to a particular set of morally criticizable values and concerns. Suppose that at t2, not only have these values and concerns persisted, they have actually increased in strength, and the agent reflectively endorses them to a greater extent than he did at t1. In such a case, then, it may be plausible to think that the agent's blameworthiness has increased over time (see Khoury Reference Khoury2013: 742). And, if so, it is possible that we readjust our blame accordingly, suggesting the possibility of a largely unexplored phenomenon that is the mirror image of forgiveness. (And just as one may make an expression of remorse by way of apology, one may make an expression of enhanced endorsement by ‘doubling down’.)

5. Conclusion

The paradox of forgiveness claims that appropriate forgiveness is logically impossible; forgiveness is never a fitting response. I have argued that the paradox is generated by an equivocation between different temporal dimensions of blameworthiness. This equivocation, in turn, is due to the common, if implicit, belief that personal identity is the diachronic ownership condition on blameworthiness. But psychological connectedness of the relevant sort, not personal identity, grounds diachronic blameworthiness. This, in turn, provides the needed explanation of the transformative power of repentance; genuine repentance makes forgiveness appropriate because it consists in breaking the relevant psychological connections that ground diachronic blameworthiness. This view has a number of significant implications with which any full theory of forgiveness must engage, largely due to the fact that while personal identity is binary and transitive, psychological connectedness is a scalar and intransitive relation.

Let me end by emphasizing the relative modesty of this view. It simply follows the implications of the claim that the property of being blameworthy for an action can diminish and extinguish across time. This claim is no more metaphysically puzzling than the claim that the property of being an insightful philosopher or a fast swimmer can also diminish and extinguish over time. When blameworthiness has reduced over time, then a reduction of blame is fitting. When blameworthiness has extinguished over time, then the cessation of blame is fitting and continued blame is unfitting. I am inclined to call the reduction or cessation of blame in light of an awareness of reduced or extinguished diachronic blameworthiness ‘forgiveness’ though perhaps you wish to call it something else.