“The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation”. Article 46 of the Indian Constitution that came into force in 1950 provides for a series of provisions favouring historically under-represented groups within Indian society.Footnote 1 Affirmative action policies, thus, appear in different parts of the world, even beyond the United States (US),Footnote 2 and may relate to particularly salient political figures such as presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson,Footnote 3 who placed such policies prominently on their political and policy agendas, as well as to more mundane attempts to correct past discrimination that emerged as a part of a policy feedback process.

Affirmative action policies are aimed to facilitate the integration of historically disadvantaged groups into society and in some cases to facilitate their equal standing. At the same time, as we elaborate in detail below, those policies are also made to politically benefit the decisionmakers. The stated aims of affirmative action policies differ between nations, as do the methods used in the name of such policies. Although the Indian and American cases of affirmative action policies are relatively familiar, the prevalence of this type of policies is almost staggering with cases ranging both historically, from the young republic of the Soviet Union (Martin Reference Martin2001)Footnote 4 to the present day, and geographically, from Asian nations (e.g. Sri Lanka; Malaysia) to Europe (e.g. France) and to Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. Nigeria) (Edwards Reference Edwards1995; Rothman et al. Reference Rothman, Lipset and Nevitte2003; Sowell Reference Sowell2004; Zhou and Hill Reference Zhou and Hill2009). In addition, those policies pertain to various aspects of political, social and public life, from education (e.g. China and US) and employment (e.g. Britain) to positions in political bodies (e.g. in India) (Eisaguirre Reference Eisaguirre1999).

Although they are prevalent around the world, affirmative action policies have proved to be a contentious topic. In most nations, in order to qualify for affirmative action policies, one needs to be a member in a historically disadvantaged group. There is tension, however, within this type of policy as the recipient of the benefits is an individual, whose biography is often irrelevant to this provision. Indeed, to receive preferred treatment, this individual does not necessarily have to be an actual victim of injustice. The provision, therefore, may discriminate against a member of a group that has not been historically disadvantaged, whose qualifications are at least equal. This is the tension between individual merit on the one hand and social justice on the other. In addition, those who benefit from the policy may be stigmatised, the policy may serve a symbolic goal rather than any social change on the ground, and a political backlash is also possible (Sowell Reference Sowell1990; Mills Reference Mills1994; Bergmann Reference Bergmann1996; Bowen and Bok Reference Bowen and Bok1998; Dworkin Reference Dworkin1998; Anderson Reference Anderson2000; Cunningham et al. 2002). The purpose of this article is not to examine affirmative action policies from a normative angle, as is too commonly done in the literature. Nevertheless, despite its empirical emphasis and positivist approach, we feel that at least a minimum reference to the normative aspects of the phenomenon under investigation is warranted. What is more, the analyses presented hereafter are sure to inform this kind of discussion. A normative discussion, we believe, is better when data, numbers and facts inform it. We aim to identify variables that systematically explain the variance between countries and over time in terms of the prevalence of this type of policies. This, in turn, will certainly contribute to normative investigations of affirmative action policies. For instance, the understanding of the tension between individual merit and social justice may be informed by our discussion of the background and past experiences of groups that benefit from such policies. As such, we should care about the antecedents of affirmative action policies, even if the focus in the literature so far has been predominantly on normative questions and the consequences of such policies.

Apart from those normative puzzles, some of the literature on affirmative action policies does examine empirical questions. A considerable amount of the literature, for instance, focuses on certain nations or on binational comparisons (Dubey Reference Dubey1991; Cahndola Reference Cahndola1992; Parikh Reference Parikh1997; Bleich Reference Bleich2003; Zhou and Hill Reference Zhou and Hill2009, inter alia). The literature that focuses on comparisons of more nations is typically normative (e.g. Sowell Reference Sowell1990, Reference Sowell2004; Mills Reference Mills1994) and fails to use quantitative large-N analysis that allows identification of variables that systematically correlate with affirmative action policies (Appelt and Jarosch Reference Appelt and Jarosch2000; Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018). In addition to political psychologists (e.g. Alvarez and Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm1997; Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005; Huber and Lapinski Reference Huber and Lapinski2006) and historians (e.g. Martin Reference Martin2001; Weisskopf Reference Weisskopf2004), legal scholars have also examined this policy extensively (e.g. Edlin Reference Edlin1999; Kellough Reference Kellough2006). Nevertheless, we know surprisingly little about what variables systematically correlate with this type of policies. The correlates of affirmative action policies are largely understudied, and research of systematic effects on this type of government action using quantitative methods is unavailable.

Given the importance of such policies and the scarcely little we know about their systematic antecedents, this article is a first attempt to examine what key variables influence the variance in those policies among different groups and nations. We, therefore, develop a theoretical framework to understand the precursors of affirmative action policies. This framework uses the policy feedback literature as its linchpin (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1988, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Ingram and Schneider Reference Ingram and Schneider1991a, Reference Ingram and Schneider1991b) and also fuses together insights from other theories pertaining to affirmative action policies. Affirmative action policies have several rationales, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and we integrate them all in the theoretical framework developed below. Those policies may aim to redress inequality resulting from past injustice. This is also known as compensatory justice. Their goal may be diversity and the related benefits, for instance in educational settings, as well as the redistribution of resources to benefit minorities (Andrews Reference Andrews1999a, Reference Andrews1999b). In our analyses, those rationales combine with what literature has indicated to be important correlates of rights creation to form a theoretical framework explaining why those policies appear. The sources of affirmative action policies include policy feedback, compensatory justice, the power of the state (political and economic) and globalisation. Data from 1985–2003 are used for the estimation of a series of fixed-effects models and cross-sectional logistic regressions to examine which variables systematically correlated with such policies and provisions. We conclude with more general comments and ideas for further development in future work.

Theory: policy feedback and affirmative action

The scholarly literature highlights the complexities of creating legal categories in a democratic reality, where equality is a key principle (e.g. in housing policy, welfare and immigration policy in Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993) and in general the extent to which public policy serves democracy (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1988, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Ingram and Schneider Reference Ingram and Schneider1991a, Reference Ingram and Schneider1991b). This article is a first attempt in the literature, to our knowledge, to systematically test claims about different explanations for affirmative action policies. As such, we form a theoretical framework that is based on the policy feedback literature. We complete the discussion by also addressing other schools of thought concerning affirmative action policies, such as those that underline the importance of compensatory justice. In this section, we briefly introduce those theories and then move on to focus on each of the correlates more specifically.

A key argument of the policy feedback literature is that politicians decide on policies on the basis of the political reactions that they get from the media, their political opponents and target audiences (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Those policies might be given rationales by the politicians and the target groups. Schneider and Ingram (Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Ingram and Schneider Reference Ingram and Schneider1995) discuss a classification scheme for such groups, which is determined according to the group’s political resources and is socially constructed as more positive or more negative. Accordingly, their categories range from advantaged (higher political resources and more positive social constructions) through dependents and contenders to deviants (lower on political resources with more negative social constructions). Each of those groups gets a different rationale for the type of policies targeting them and the implications of those policies (Beland Reference Beland2010). Policy feedback (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992; Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Mettler Reference Mettler2002) is the idea that policies influence the political reality in terms of the legitimacy of the political order, mobilisation, inclusiveness and even the formation of political beliefs. Policies are politically consequential. Policy design can be used as a political strategy by elites to alter the preferences, beliefs and behaviours of organised interests, targets of public policy and the masses (Wichowsky and Moynihan Reference Wichowsky and Moynihan2008). Nevertheless, the effects of policy design on mass public opinion may be quite limited (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007). Affirmative action may influence social construction in the citizenry or as Mettler and Soss put it: “policies convey messages about group characteristics directly to members of a target group and to a broader public audience” (Reference Mettler and Soss2004, 61). The policy feedback literature helps us explain why governments have an incentive to take the interest of minority groups – as well as members of the majority who favour egalitarianism – into account. As rational actors driven by opportunity, incentives and constraints, governments enact such policies, we argue, within the rationales provided by the policy feedback literature.

A key lesson from the policy feedback literature is applied here to the emergence of affirmative action. Policy feedback literature suggests that specific policies have consequences on the side of the constituencies, particularly in terms of political activation, which then feeds back to the process of policy formulation and becomes important for subsequent actions of the government. In the case of groups being discriminated against, this type of dynamics should be of relevance if these groups, or their promoters, become influential – in terms of structure of social construction. Consequently, the government has an interest to implement remedial policies. A key element here is whether democratic institutions are in place to lower suppression of minorities and facilitate their political organisation and power (e.g. Parikh Reference Parikh1997).

Democracy, economic conditions and modernisation

After discussing the ways in which policy feedback theories help account for affirmative action policies, we now zoom in on the specific variables this theoretical framework suggests would systematically correlate with affirmative action policies. Those include the effects of democracy, relocation of minorities, modernisation and economic development. After discussing those, we also address our two control variables: globalisation and a history of violence.

Democratic conditions

Affirmative action policies are “state imposition, through legislation, court judgments or other mechanisms”. Those policies “reflect intervention by the state to ensure access to employment, education, legislative seats and other appropriate societal goods, for targeted groups” (Andrews Reference Andrews1999a, 3). In the context of policies remedying political discrimination, democracy should play a major role. In a developing democracy, resources would be invested in creating and stabilising democratic institutions and in instituting rights and liberties. Such democracies would aspire to project an image overseas as abiding by international norms of political equality. As such, even their resources are a bit stretched because of the effort to establish a democratic form of government; our argument is that they will invest resources towards establishing affirmative action policies. What is more, when democratic institutions are consolidated, the state is better positioned to remedy past political discrimination. Thus, democratic conditions should positively correlate with affirmative action, which is particularly evident given insights from the policy feedback literature. Within this literature, policies are politically consequential. Politicians would decide on affirmative action policies if those would favour their political fortunes. In a political environment that is more democratic, we would expect more positive political reactions from the media, political opponents and target audiences, if such liberal policies are enacted (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007; Wichowsky and Moynihan Reference Wichowsky and Moynihan2008). This is particularly true if such policies are given rationales to justify them by the politicians that would satisfy their target groups. The actions of the American presidents mentioned at the beginning of this article (JFK and LBJ) are clear examples of this policy feedback loop and its ramifications; the leader enacts policies that would benefit him politically given his framing of those policies and their future perceptions among his target audiences.

We argue that residing in a democracy should be correlated with a greater likelihood for affirmative action policies for the minority group (Hibbs Reference Hibbs1973; Mitchell and McCormick Reference Mitchell and McCormick1988; Poe and Tate Reference Poe and Tate1994). The attempt to remedy past wrongs is more likely to take place in strong democratic states (Wilensky Reference Wilensky2002). In India, Parikh (Reference Parikh1997) argues that democratic conditions allowed both lower castes to participate in and benefit from the political process and higher castes to gain a new appreciation of the importance of equality after living under British rule [p. 71; and in America the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Weisskopf Reference Weisskopf2004)]. Improved democratic conditions would be particularly important for affirmative action policies related to political discrimination. Beyond policy feedback, judicial decisions may also induce policy implementation especially in established democracies (e.g. the Brown versus Board of Education ruling of the Supreme Court of the US). Even a cursive look at our data would suggest that the likelihood of affirmative action policies is approximately twice as large among democracies compared with nondemocratic systems. We provide a more systematic explanation of this hypothesis in the multivariate analyses below.

H1: Affirmative action policies redressing political discrimination are more likely the more democratic the country is.

Minorities relocated from a different nation are less likely to benefit from affirmative action policies as they are less integrated into the democratic system. The logic of policy feedback theory would suggest that such groups are less likely to be considered by decisionmakers. Politicians would not think of such groups as ones that would yield the political benefits associated for them with the implementation of affirmative action policies. Transferred groups are likely to be at a disadvantage as they were relocated from one country to another. Consequently, those groups are less likely to be politically organised, they are not connected to institutions that translate group interests into policymaking (such as political parties) and so on. What is more, such groups may also be less likely to make compensatory justice claims. Being from outside the country, and thus in little, or virtually no, contact with the majority, a minority group that was relocated from a different nation should be unlikely to expect compensatory justice. On the basis of both the policy feedback literature and compensatory justice, we expect transfer from another state to systematically correlate with a decreased likelihood of affirmative action policies. Group name, country and year of transfer are available in the Appendix.

H2: Relocation from a different nation should correlate with a decreased likelihood of affirmative action policies for the group.

Modernisation

In a variety of ways, such as through increased literacy, education and cultural change, modernisation can change the view of who should be accepted in society and who should be protected by the state. Within the policy feedback framework, a modernising polity would feature growing postmaterialistic constituencies that would be likely better integrated into international standards and norms and would demand egalitarian policies. This would be an incentive for leaders to enact policies in this spirit and a constraint against rescinding such policies in case they are already in place. The logic of policy feedback, thus, suggests that modernisation would correlate with a greater likelihood of affirmative action policies. What is more, modernisation has been shown to act as a causal variable in increasing levels of democracy generally (Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski and Limongi1997) and specifically enhancing the rights of minorities (Steel et al. Reference Steel, Warner, Stieber and Lovrich1992; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003). We expect modernisation generally, and its education component specifically, to correlate with greater likelihood of compensatory discrimination. Affirmative action policies will be more likely in places with a more highly educated populace. Education produces greater tolerance, more acceptance of diversity and less xenophobia (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). Consequently, there would be a greater inclination to be more accommodating to oppressed minorities. Knowledge distribution measures levels of modernisation and education well, as it reflects literates as percentage of adult population and percentage of students (Vanhanen Reference Vanhanen2003). We expect a net effect of economic and democratic conditions, but in addition we expect an independent effect of modernisation, measured here as knowledge distribution.

H3: With modernisation, affirmative action policies should be more likely.

Another important aspect of modernisation is the economic resources of the state. Possible correlates here include the per capita gross domestic product. Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, as well as measures derived from this variable (such as the share of government spending as a percentage of GDPFootnote 5 ), may be a useful measure. When it comes to discrimination in general and economic discrimination in particular, when the state has the ability to muster considerable economic resources, as reflected in its GDP per capita, the likelihood of positive discrimination for the group should increase.

H4: GDP per capita positively correlates with the outcome variables, in particular when we test for Economic Affirmative Action.Footnote 6

Control variables

Globalisation

Parikh (Reference Parikh1997, 29) argues that exogenous forces to the political system may antecede affirmative action policies. We argue that increased levels of globalisation would increasingly expose the system to external forces that influence the rights of minorities in general and the likelihood of affirmative action policies in particular (Wald et al. Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996; Cole Reference Cole2005). When a principle like remedial action to compensate for past violence or discrimination becomes institutionalised in world culture and linked closely to other highly institutionalised principles such as human rights ideology, it takes on a normative character and gradually reshapes the policies and identities of states and other actors (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997). We expect that minority groups in globalising countries would benefit from affirmative action policies (Finnemore Reference Finnemore1996; Boli and Thomas Reference Boli and Thomas1997, Reference Boli and Thomas1999; Ramirez and McEneaney Reference Ramirez and McEneaney1997; Hollingsworth Reference Hollingsworth1998). Through a process of “norm cascade” (Tsutsui and Wotipka Reference Tsutsui and Wotipka2004), in a globalised state, political entrepreneurs, public opinion, political organisations and social movements are able to recognise alternative legal arrangements and through a policy feedback loop this will correlated with a greater likelihood that leaders would pass affirmative action policies. In the work of Risse et al. (Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikkink1999), a norm that emerges in the global society influences domestic politics, as well as the behaviour of individuals and organisations worldwide (see also Sunstein Reference Sunstein1997; Krücken and Drori Reference Krücken and Drori2009). We argue that in the case of affirmative action policies, there is a norm cascade between countries (Ramirez et al. Reference Ramirez, Soysal and Shanahan1997).Footnote 7

Of relevance here is also the literature on EU anti-discrimination laws and their application (Amiraux and Guiraudon Reference Amiraux and Guiraudon2010). International legal provisions constrain domestic politics and decisionmaking at the national level (Amiraux Reference Amiraux2005). The moral and ethical values that are embedded in the larger international frameworks by the international community mean that nation-states are restricted in how they handle their internal affairs (Bell Reference Bell2008). The European Union’s anti-discrimination and racial equality directives are a case in point (Bell Reference Bell2009; Evans and Givens Reference Evans and Givens2010)Footnote 8 and indicate the broader phenomenon we argue here. In sum, ceteris paribus, our control for globalisation should correlate with a greater likelihood that the state enacting affirmative action policies.

Compensatory justice and a history of violence

In addition to the policy feedback theoretical reasoning, one of the key reasons cited for affirmative action policies in the literature is the notion of compensatory justice. Section 9 of the South African Bill of Rights, which has served as the constitutional underpinning for affirmative action policies in this countryFootnote 9 (Jagwanth Reference Jagwanth2004), captures the heart of the compensatory justice argument. The provision states that “Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken”. Compensatory justice, therefore, is the idea that groups that have been historically discriminated against are being compensated for as a result of these policies. Examples for historical injustice towards certain groups abound. In the US, African-Americans have endured injustice at the hands of White Americans first in the form of slavery. Although there is record of some white and Native American slaves, slavery by and large was racialised and consisted mostly of individuals of African decent. This was true in the US since at least a century before the foundation of the republic and until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865. Nevertheless, the post-Civil War constitutional amendments did not mark the end of discrimination against blacks. The Jim Crow laws created a segregated system in the Southern American states with their doctrine of “separate but equal” endorsed by the Supreme Court.Footnote 10 Following a number of political events, including the end of the Second World War and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, the notion that blacks should not only win equal protection under law but also be compensated for past injustice became central in American politics. Indeed, part of this trend led to the creation of affirmative action policies, which as mentioned above started in the early 1960s with Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Yet, compensatory justice was not limited to the US.

On the basis of Hindu scriptures, the caste system in India created four groups (varnas) with a different social status for each. In addition, the untouchables (also known as Parjanya or Antyaja and self-described as Dalits) were a group outside the varna system. Although the scriptures themselves do not necessarily dictate segregation between the groups, in reality considerable levels of caste-based discrimination existed in Indian society and politics (Berreman Reference Berreman1975; Galanter Reference Galanter1984; Chowdhary Reference Chowdhary1998). To correct those wrongs, the Indian state’s reservation policies guaranteed exclusive access (e.g. with the use of quotas) to members of lower castes, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes [of which the untouchables are the largest group (Mendelsohn Reference Mendelsohn1999)]. Affirmative action policies in India date back to colonial times; pursuant to the recommendations of the Miller Committee, in 1918 the State of Maysor established affirmative action policies in the public service (Mendelsohn and Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998).

Past discrimination against Americans of colour in the US or against Dalits in India as such is rarely debated. The extent to which other groups suffered historically, however, is often a contested issue. Indeed, the choice of individuals to schools, government positions or jobs, based on group affiliation (rather than their individual qualities alone), rarely goes unchallenged (Mills Reference Mills1994; Cohen Reference Cohen1995; Orfied Reference Orfied2001). When the benefits associated with affirmative action policies are concerned, this debate often turns acrimonious. In the US, for instance, it is not quite clear whether affirmative action policies towards Latinos find justification in historical discrimination. The same may be true for Asian Americans in America, and for a variety of other groups elsewhere.

To measure the extent to which compensatory justice leads to affirmative action policies, we attempt to circumvent normative debates around historical injustice. As the scope of this article will not allow delving into each case of historical injustice of each of the groups studied, we control for whether clear abuse results in affirmative action policy. Although historical injustice may be inflicted in different shapes and forms, it is quite clear that groups that suffered violence in the past most probably fall into this category. The more violence a minority group endured in the past, the more injustice was handed to it. In sum, we expect our control of a history of violence to correlate with higher levels of affirmative action policies.

Data and methods

The analyses are based on data for 232 groups from 150 countries for the period 1985–2003. A very wide range of groups was studied (e.g. Native Americans in the US, Druze in several nations and Yoruba in Nigeria). If groups resided in more than one nation, they were included more than once (see Appendix for more details). On average, data for over 15 years are available for each of the groups.

The MAR projectFootnote 11 is an independent, university-based research project monitoring and analysing status and conflicts of communal groups in all nations with a population of at least half a million people.Footnote 12 The Minorities at Risk data set developed in four phases: Phase I covered 227 communal groups from 1945 to 1989; Phase II covered 275 groups from 1990 to 1995; Phase III covered 275 groups from 1996 to 1998; and Phase IV covered 285 groups from 1998 to 2000.Footnote 13

Three dependent variables were coded for the purposes of this study; Political Affirmative action policies is coded 1 for cases where there were explicit public policies designed to protect or improve the group’s political status. The MAR coding for this variable examines the role of public policy and social practice in maintaining or redressing political inequalities. This pertains to clear under-representation in political participation owing to historical neglect or restrictions. Similarly, it pertains to substantial under-representation in political office for the specific group in the particular country. The coding is 0 otherwise. That is, in cases in which the formal public policies towards the group are neutral, the coding was 0. Along the same lines, in some cases the policies were positive but essentially inadequate to redress inequality and offset discriminatory policies. The coding was 0 here again. Finally, when public policies substantially restrict the group’s political participation (in relative terms to other groups), then the coding was 0 again. The second outcome variables, Economic Affirmative action policies, was coded 1 for cases in which there were explicit public policies designed to protect or improve the group’s material well-being. The MAR coding for this variable examines the roles of public policy and social practice in maintaining or redressing economic inequalities. The economic aspects used in the coding scheme include issues of significant poverty, as well as under-representation in desirable occupations that stems from historical marginality, neglect or restrictions. Similarly, significant poverty or under-representation in desirable occupations that are due to prevailing social practice by dominant groups are also coded. The coding is 0 otherwise. That is, when there are few or essentially no public policies intended to improve the group’s material well-being, the coding was 0. Likewise, when formal public policies toward the group are inadequate to offset levels of discrimination. Along the same lines, when public policies restrict the group’s economic opportunities in a way that is significantly more substantial than for other groups, the coding would be 0.Footnote 14 The level of correlation between Economic and Political Affirmative action policies is relatively low at 0.48. This suggests that they indeed represent somewhat dissimilar phenomena that merit studying separately, as well as studying jointly as an overall phenomenon. Accordingly, Affirmative action policies is coded 1 when there is some type of affirmative action policy in place. To tap the different phenomena, we estimate separate models for Economic Affirmative action policies, Political Affirmative action policies and Affirmative action policies of either political or economic nature.

As for the independent variables in the models, Group Transferred from Another State is equal to 1 if either the group was physically transferred or if the territory the group resides in was transferred into another state’s political jurisdiction, which includes conquest, secession and border changes due to decolonisation. Similarly, population exchange between states including forced migration leads to a coding of 1 in this variable. The coding is 0 otherwise (for details of pertinent groups and countries, see Appendix). To measure Democratic Conditions, we utilise the POLITY score, ranging from −10 (least democratic) to 10 (most democratic) (Hadenius and Teorell Reference Hadenius and Teorell2005). The measure for modernisation is Knowledge Distribution. According to the Quality of Government Database, this is the arithmetic mean of per cent of students and literates as percentage of the population (Vanhanen Reference Vanhanen2003). GDP per capita, the indicator for economic resources in the state, is measured in constant US dollars at base year 2000 (Gleditsch Reference Gleditsch2002). Missing data were imputed by using the CIA World Factbook and through extrapolation. To measure globalisation, we use the KOF Index of Globalisation (Dreher Reference Dreher2006; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Gaston and Martens2008). The KOF index is widely used in the literature and the way in which it is computed is largely in line with the standard in comparative public law (Tsutsui and Wotipka Reference Tsutsui and Wotipka2004). The globalisation indexes range from 0 to 100. Higher values indicate higher levels of globalisation. The overall index of globalisation is the weighted average of Economic Globalisation, Social Globalisation and Political Globalisation. The measure for economic globalisation is defined as the long distance flow of services, goods, capital, information and perceptions that accompany market exchanges. This index not only measures actual flows of trade and investments, but also trade restrictions, such as tariff rates (Dreher Reference Dreher2006; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Gaston and Martens2008). The index of political globalisation is measured by the number of embassies and high commissions in a country, the number of memberships the country has in international organisations, participation in UN peace-keeping missions and the number of international treaties signed since 1945 (Dreher Reference Dreher2006; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Gaston and Martens2008). Last, the social globalisation measure includes three categories of indicators: personal contacts (e.g. telephone traffic and tourism), information flows (e.g. number of internet users) and cultural proximity (e.g. trade books and number of warehouses of Ikea per capita) (Dreher Reference Dreher2006, 2008). History of Violence is measured on a scale of 0 (no violence) to 6 (warfare). More specifically, the variable ranges across the following levels: no violence, acts of harassment, political agitation, sporadic violent attacks, anti-group demonstrations, rioting and then warfare.

We use time-series cross-sectional data listing all group-country-year units for the years 1985–2003. Some of the groups appear more than once. This is true, for instance, for groups residing in territories divided between the jurisdictions of several states. As for the empirical models estimated, as affirmative action policies are instated but then in some cases are removed at a later point in time, the nature of the dependent variable is such that it can change from 0 to 1 but then revert back to 0. This renders event history analysis less appealing. If the American case is any indication, the adoption of affirmative action policies is not irreversible; recent rulings by the Supreme Court of the US have limited the scope of affirmative action policies in this country and have put into question the future of such policies.Footnote 15 As event history analysis is less appealing, we ran a Breusch-Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test, which yielded a highly significant result (χ 2 (01)=2,953.64; prob>χ 2=0.0). This leads us to reject the possibility of a simple ordinary least squares regression model. The Hausman test for fixed-effects versus random-effects models yielded a significant result (χ 2 (8)=124.75; prob>χ 2=0.0), which led us to reject the random-effects option. Accordingly, fixed-effects models are reported below. Results are reported for standardised and nonstandardised coefficients (in Appendix) for the fixed-effects models. In addition, to account for groups nested in country-years, we estimate a multilevel model with country fixed effect (reported in Appendix). As those models require that all time invariant predictors be removed from the model specification owing to perfect collinearity and in order to show the robustness of our findings while at the same time allowing for broader model specification, we also report the results of simple cross-sectional logistic regression models (in Appendix). Also in the Appendix, we report the results of models specifying a time trend variable to ensure that the results are not due to spurious time effects.

Results

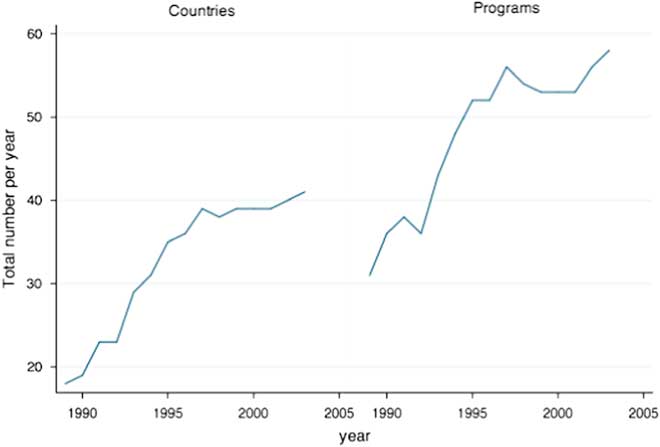

To provide a preliminary test for the effects of globalisation and the notion of a norm cascade, we plot the growth of affirmative action policies over time. The panel on the left in Figure 1 shows the total number of countries each year in which at least one affirmative action policy was in place. In the panel on the right, the total number of programmes worldwide per year is plotted over time. The graphs lend preliminary support to our hypothesis concerning the effects of globalisation. In both cases, the curves start out slowly (which is a continuation of a similar pattern during the late 1980s) and then in 1993 and 1994 bend sharply upwards, indicating a global cascade of countries adopting such policies. This trend is true both for the total number of policies worldwide and for the number of countries with such policies. In the multivariate analyses discussed below, we further substantiate that this effect of globalisation is systematic in different countries and over time.

Figure 1 The effect of globalisation: a norm cascade.

With this preliminary support for the effect of globalisation in mind, we move forwards to examine what variables systematically predict affirmative action policies. Table 1 lends strong support to our key hypotheses. The models in Table 1 include predictors of affirmative action (Model I), political affirmative action (Model II) and economic affirmative action (Model III). In Table 1, we report the results of the fixed-effects models with the variables rescaled to a range of 0–1 for comparability between coefficients.Footnote 16 In the Appendix, we report the same models with the variables ranging along their original scales (Table A.5).

Table 1 Hierarchical fixed-effects models – standardised coefficients predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic)

Notes: GDP=gross domestic product; LR=log ratio.

***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, #p<0.1, one-tailed tests where directionality hypothesised.

Sources: MAR Database; Quality of Government Database.

The results in Model I in Table 1 lend strong support to our hypotheses. A history of violence has a positive and significant coefficient, which indicates that this would strongly correlate with a likelihood that a group would benefit from affirmative action policies. The coefficient on Democratic Conditions is positive and statistically significant. The same is true for the coefficient on GDP per capita, which is highly significant. More democratic countries and those that are stronger economically are more likely to instate affirmative action policies. Groups transferred from another state owing to a host of reasons (see a detailed discussion of this variable above) are significantly less likely to enjoy affirmative action, as the coefficient on this variable is negative and significant. The coefficient on knowledge distribution is positive and significant. As knowledge distribution increases, so does the likelihood of affirmative action policies. The effect of globalisation is highly significant and positive, indicating that countries that are better integrated into the world community are also more likely to put in place affirmative action policies. The control of political inclusiveness has a negative and significant effect. As political inclusiveness increases, the likelihood of affirmative action decreases in a statistically significant manner. The most salient difference between Models II and III is the significant effect of Democratic Conditions in Model II, which examines effects on political affirmative action, and conversely the significant effect of GDP per capita in Model III that examines the effects of economic affirmative action policies. Apart from that, in both models, globalisation and transfer from another state have significant and consistent effects. The nonstandardised results in Table A.5 underline the major influence of GDP per capita. Similarly, the effects of globalisation (Models I–III) and knowledge distribution (Models I and III) are clear in Table 2. The average marginal effects suggest that when democracy, modernisation, GDP and globalisation are set to their mean and groups are not transferred from another state and there is no history of violence, the likelihood of political affirmative action is 0.102. The same values yield a likelihood of 0.097 for economic affirmative action. The likelihood for general affirmative action is markedly greater at 0.152.

Table 2 Hierarchical fixed-effects models predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic)

Notes: GDP=gross domestic product.

Robust standard errors. Results remain substantively indistinguishable when standard errors are not robust.

***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, #p<0.1, one-tailed tests where directionality hypothesised.

As reported in the Appendix, the results for the cross-sectional models in Tables A.6 and A.7, fixed-effects models in Table A.8 (controlling for spurious time effects) and Table A.9 (multilevel models with country fixed effects controlling for spurious time effects) largely substantiate the findings and lend further support to our key hypotheses. Our results are robust to varying data sources and model specifications.

Discussion and conclusions

Given the importance of affirmative action policies and the little we know about their systematic antecedents – and in particular in a comparative framework – the goal of this article was to examine what key predictors influence the variance in those policies among different groups, various nations and over time. Policy feedback literature and its predictions in addition to theoretical frameworks examining compensatory justice form the theoretical basis for our argument. The key message of this study is that indeed certain variables systematically predict the likelihood that a group benefits from affirmative action policies redressing past political or economic discrimination. Beyond the case studies and small-N comparisons appearing in the literature on this topic, we identify a set of predictors with regular effects and use the preliminary theoretical framework proposed here to explain the mechanisms underlining these effects. As such, our work makes considerable contribution to the extant scholarship not only by shifting the focus from the consequences of affirmative action policies to their predictors, but also in providing a systematic analysis of those predictors. These empirical and theoretical contributions are bound to inform the normative debates concerning positive discrimination.

According to our theoretical framework, policy feedback would lead decisionmakers to consider the political consequences of the policies they make, and they would tailor those policies to specific constituencies, with the media and political opponents and allies in mind. This logic explains the effects of democratic conditions, groups transferred from another state, modernisation and knowledge distribution, economic conditions and globalisation. In rectifying political discrimination, it is crucial for the state to have considerable democratic resources in the form of democratic institutions and well-established civil rights and civil liberties. Although the link between democracy and affirmative action has been made in the literature, this is the first time this link wins empirical support for its systematic nature. An additional antecedent is modernisation. Measured as the level of education among the populace, modernisation strongly correlates with a greater likelihood of affirmative policies; education produces greater tolerance, more acceptance of diversity and less xenophobia, thus an inclination to be more accommodating to oppressed minorities. With the growth of postmaterialist constituencies, decisionmakers are more likely to cater to such groups and the norms they endorse by making affirmative action policy. GDP is key for the state to have sufficient power to muster the economic resource necessary for action to remedy discrimination. Exogenous forces – such as increased levels of globalisation, which expose the system to the norm cascade of international standards of equality and rights – correlated with a greater likelihood of affirmative action policies. When a principle like remedial action to compensate for past violence or discrimination becomes institutionalised in world culture and linked closely to other highly institutionalised principles such as human rights ideology, it takes on a normative character and gradually reshapes the policies and identities of states and other actors. This effect of globalisation on affirmative action policies has been largely understudied in the literature, with virtually no test of its systematic nature. What is more, we link it to more recent literature on anti-discrimination provisions in the European Union. Compensatory justice is another precursor we identify for affirmative action policies. This is the notion that historically discriminated groups are being compensated for as a result of these provisions. Groups that suffered violence are more likely to enjoy the advantages in those policies.

We do not intend to discount the significance of public opinion (Brace et al. Reference Brace, Sims-Butler, Arceneaux and Johnson2002; Haider-Markel and Kaufman Reference Haider-Markel and Kaufman2006) or the critical role social movements play for rights (Barclay et al. 2009). In fact, some of the variables we study may be conducive to shifts in public opinion and may result in higher levels of activity of social movements. This kind of policy feedback loop may transpire, for instance, in a globalised and modernised nation, where the polity is more likely to be informed of changing global standards. Changes in public opinion may follow suit. Along the same lines, economic development may result in more resources made available for campaigns (legal or otherwise) waged by social movements. Barring issues of data availability, we would include control variables for public opinion and for the role of social movements in our models.

This project is innovative theoretically as well. First, we develop a comprehensive framework to explain affirmative action policies using the policy feedback literature and with additions from other schools of thought such as compensatory justice. Much of the literature on this topic has either addressed normative questions around those policies, or tested its effects on education, equality or politics (Matsuda Reference Matsuda1988; Kennedy Reference Kennedy1990; Coate and Loury Reference Coate and Loury1993; Cantor et al. Reference Cantor, Miles, Baker and Barker1996, inter alia). Nevertheless, we know surprisingly little about what accounts for the existence of these policies in the first place. We believe that this allows to illuminate some fundamental questions and move some of the debates in the literature forward – an understanding of the roles of policy feedback and compensatory justice with respect to affirmative action policies serves the broader debates around those topics with respect to affirmative action in the US, positive discrimination in India and other variants of such provisions elsewhere (Roosevelt Reference Roosevelt1990; Reskin Reference Reskin1998; Welch and Gruhl Reference Welch and Gruhl1998).

This work provides some interesting predictions for groups residing in different nations, as well as for the likelihood of affirmative action policies as time goes by. Although it does change between groups and between nations, as the findings in the Appendix suggest, the type of group does not change over time. This variable, hence, would correlate with the initial likelihood of affirmative action policies but would have little influence on variance in the dependent variable over time. On the other hand, a country may become more powerful and democratic institutions may consolidate over time. Similarly, modernisation and gross domestic product may fluctuate as years go by. Thus, in a nation that opens up to global trends or in one where modernisation is increasingly taking a hold, the probability of positive discrimination increases. As for the cross-sectional perspective, comparing nations with higher levels of modernisation with those with less modernisation, we expect the former to be more likely to have affirmative action policies. The same applies to richer nations and to nations with a more powerful democratic state.

At the empirical level, this work is novel in more than one way; we use quantitative methodologies, analyse data for hundreds of groups from a multitude of nations and examine changes both across nations and over time. This marks a significant departure from methodologies used in the extant literature on affirmative action policies, which offers work based mostly on qualitative methodologies and only in a limited number of countries.

Acknowledgements

U.S. would like to thank the Israel Institute in Washington, DC and the Institute of Israel and Jewish Studies, SIPA and the Department of Political Science at Columbia University of New York for their support during the time this research was conducted at Columbia University.

Appendix

Table A.1 Correlation matrix

Table A.2 Descriptive statistics

Table A.3 Minority groups included in analyses

Table A.4 Transfer (group, country and year)

Table A.5 Hierarchical fixed-effects models predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic)

Table A.6 Cross-sectional logistic regression models predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic)

Table A.7 Cross-sectional logistic regression models – standardised coefficients predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic)

Table A.8 Controlling for spurious time-effects predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic) with a time trend variable

Table A.9 Multilevel models with country fixed effects controlling for spurious time-effects predictors of remedial policies (general, political and economic) with a time trend variable