Shared pain is common in religious practices, team-building exercises and military training. Bastian, Jetten, and Ferris (Reference Bastian, Jetten and Ferris2014; hereafter BJF) found that compared with shared painless activities, shared painful activities induced more cooperative behavior in economic decision-making tasks. They posited that pain acts as social glue that enhances the bonds between people. A growing number of subsequent studies have supported this hypothesis (e.g., Knight & Eisenkraft, Reference Knight and Eisenkraft2015; Vardy & Atkinson, Reference Vardy and Atkinson2019; Wang, Gao, Ma, Zhu, & Dong, Reference Wang, Gao, Ma, Zhu and Dong2018). However, these contradict the prevailing belief that negative experiences will cause people to escape from social reality, leading to propersonal rather than prosocial behavior, and that painful stimuli, even when shared, can induce antisocial behavior (Staub, Reference Staub, Carlo and Edwards2005). We think this contradiction exists because shared pain is not exactly equal to pain. If we do not consider the contribution of sharing, can pain play the role of social glue, as BJF suggest?

Some studies have noted the respective effect of negative experiences and sharing. In a recent review article, Vollhardt (Reference Vollhardt2009) systematically analyzed altruistic and prosocial behaviors caused by painful experiences and explained in detail how, from a social psychology perspective, people who share similar negative experiences were affected by such behaviors. He believes that it is important to classify whether pain events are experienced alone or with others. People who experience negative events are more likely to help people who share their experiences than to help people who have different experiences. However, people who have experienced negative events can be willing to help others as long as they perceive that their experiences share a certain degree of similarity with the others. Knight and Eisenkraft (Reference Knight and Eisenkraft2015) examined the role of shared negative emotions in interpersonal connections and found that sharing such experiences undermined interpersonal connections in continuous tasks but promoted interpersonal connections in one-shot tasks. They speculated that with continuous tasks, the effect of shared negative emotions was mainly derived from negativity rather than sharing, while for one-shot tasks, the effect of shared negative emotions was mainly derived from sharing rather than negativity.

The above studies only focused on interpersonal trust and cooperative behavior resulting from shared painful experiences but did not investigate the same behavior when negative experiences are not shared. However, in real life, negative experiences are shared and unshared. To test whether the conclusion of BFJ that pain acts as social glue can be generalized, we need to investigate the context where pain is not shared. Moreover, to logically elucidate the relative roles of negative experiences and sharing, we need to add the unshared condition and compare shared and unshared experiences.

To investigate whether sharing moderates the effect of pain on cooperation, we performed two experiments based on the BJF study. Experiment 1 re-examined the robustness of the main BJF findings, testing whether shared pain in Chinese subjects enhanced interpersonal bonding and cooperative behavior. In experiment 2, we added unshared conditions. So, the study comprised pain versus no-pain and shared versus unshared to explore the relative effect of pain and sharing on interpersonal bonding and cooperative behavior. Moreover, because studies have shown that empathy triggered by witnessing others’ suffering can promote prosocial behavior (de Waal, Reference de Waal2008; Vardy & Atkinson, Reference Vardy and Atkinson2019), we attempted to examine the mediating role of empathy. At the same time, we also examined the mediating role of bonding.

Experiment 1

We replicated two of BJF’s experimental designs to re-examine how shared pain affects bonding and cooperative behavior. Our study imitated the main processes outlined by BJF and recruited participants using similar inclusion criteria. The instructions, pain stimulus and items measured were from BJF. Notably, we only replicated their first two studies because studies 2 and 3 had the same aim, but the pain stimulus in study 2 has been more widely used in previous research (Walsh, Schoenfeld, Ramamurthy, & Hoffman, Reference Walsh, Schoenfeld, Ramamurthy and Hoffman1989). Finally, we measured empathy to test its possible mediating effect.

Methods

Participants

Power analysis (power = 80%) using G*power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) for an expected medium to large effect (Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey, & Leknes, Reference Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey and Leknes2014) suggested a sample size of at least 70 participants was needed. We recruited 80 students from East China Normal University using a participant recruitment platform. However, two participants voluntarily withdrew from the experiment because they could not withstand the induced pain. Three additional participants were not allowed to participate because they were more than 3 minutes late. Our final sample size was 75 (57 females, M age = 20.97 years), which was similar to BJF’s sample sizes (in study 1: N = 54, 72.2% female, M age = 22.24 years; in study 2: N = 62, 75.8% female, M age = 21.87 years). Our final group sizes ranged from 3 to 4, with a median of 4 and a mean of 3.75. Participants were compensated for their participation.

Procedure

We obtained written informed consent from participants and then randomly assigned them to either the shared pain condition groups (N = 39, 10 groups) or the shared no-pain condition groups (N = 36, 10 groups). The pain stimulus in our study was modeled on that of BJF. Each participant in the pain condition immersed his or her nondominant hand into a vessel filled with ice-water (<3°C). At the bottom of each vessel there were several metal balls and a plastic container with a small hole. Participants were asked to place one ball into the container through the hole at a time. They were instructed to keep their nondominant hands in the water for as long as possible until they could not bear it (when 90 seconds had elapsed, the experimenter terminated that portion of the experiment). Next, the participants were asked to stand side by side in front of the same wall in the lab. They were instructed to maintain an upright wall squat that induced muscle aches for as long as possible (when 60 seconds had elapsed, the experimenter terminated the task). For the no-pain condition, participants located metal balls under room-temperature water (>24°C) for 90 seconds, and then balanced on one leg for 60 seconds, during which time they could switch legs freely and use balance aids to avoid any fatigue (see the Appendix for the instructions).

Next, participants completed the empathy questionnaire (see the Appendix), which included six items: “sympathetic”, “soft-hearted”, “warm”, “compassionate”, “tender”, and “moved” (α = .94). Each item was rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely).

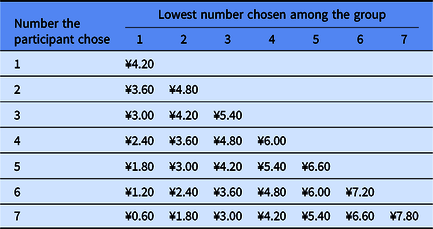

Afterward, we replicated BJF’s methods of measuring both bonding and cooperation. We administered a questionnaire (see the Appendix) containing seven items (α = .93; e.g., “I feel a sense of solidarity with other participants”) to measure whether the participants had bonded with each other. Answers were scored using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).Footnote 1 The participants then played six rounds of an economic-game paradigm (the weak link coordination exercise) in groups (see Table 1). In each round, each participant silently chose a number from 1 to 7. The payoff was a function of the lowest number chosen among the group and the number the individual participant chose. Participants could earn the best score only if all members chose 7. However, when group members chose different numbers, the smaller the number a participant chose, the greater the payment he/she would receive. If participants did not expect that the others would choose high numbers, they might choose low numbers. Participants who chose 1 were the least cooperative because they could get a moderate payoff at the cost of the group’s economic outcomes. In contrast, participants who chose 7 were the most cooperative because they made it possible to maximize the group’s economic outcomes, but at the risk of being defected and receiving a very low individual payoff. Participants wrote down their choices, and the experimenter announced the smallest number chosen and began the next round. Participants only knew the smallest number chosen in the group and his/her own payoff. Participants were told that their payment was based on their outcomes in a random round of the economic games at the end of the experiment.

Table 1. Payoff schedule for the weak link coordination exercise

Finally, participants answered the manipulation check questions: “How intense was the pain you experienced?” (0 = not at all painful, 10 = intensely painful) and “How unpleasant was the pain you experienced?” (0 = not at all, 10 = the most intense bad feeling imaginable). Last, participants filled out demographic questions and were debriefed.

Results

Manipulation check

An independent-samples t test of pain ratings was conducted. The results of pain intensity showed that the participants in the shared pain condition (M = 6.62, SD = 1.76) reported significantly greater pain intensity than the participants in the shared no-pain condition (M = 1.36, SD = 0.59), t(73) = 17.07, p < .001, d = 4.00. The results of pain feeling showed that the participants in the shared pain condition reported more unpleasant pain feeling (M = 6.26, SD = 2.19) compared with the shared no-pain condition (M = 1.56, SD = 0.88), t (73) = 12.04, p < .001, d = 3.21. These results suggested that the pain manipulation was effective.

Empathy, bonding, and cooperation

Empathy

The results showed that the participants in the shared pain condition (M = 3.06, SD = 1.49) significantly felt highly empathic compared with the participants in the shared no-pain condition (M = 1.69, SD = 1.29), t(73) = 4.23, p < .001, 95% CI = [.72, 2.00], d = .99.

Bonding

The participants in the shared pain condition felt more bonding to others (M = 4.27, SD = 1.08) compared with those in the shared no-pain condition (M = 3.77, SD = 1.53), t(73) = 1.66, p = .10, 95% CI = [−.10, 1.11], d = .39.

Cooperation

The average number for the six trials of the weak link coordination exercise was indexed as cooperative behavior. Participants in the shared pain condition cooperated significantly more (M = 4.66, SD = 1.16) than those in the shared no-pain condition (M = 3.93, SD = 1.78), t(73) = 2.14, p = .04, 95% CI = [.05, 1.42], d = .50.

Mediation analysis

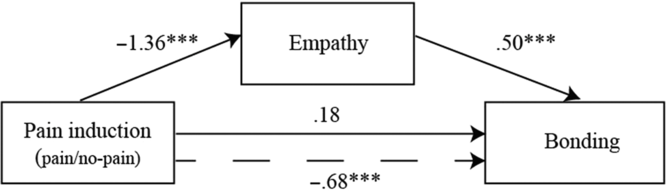

Mediating effect of empathy between pain and bonding (Figure 1)

The bootstrapping method for mediation (5000 bootstrap samples, model 4, Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008) was applied. The results showed that the direct effect of pain on participants’ perceived bonding was not significant, direct effect = .18, SE = .29, 95% CI = [−.40, .75]; the indirect effect of pain on participants’ perceived bonding was significant, indirect effect = −.68, SE = .19, 95% CI = [−1.15, −.39].

Figure 1. The mediation effect of empathy between pain induction (pain condition, no-pain condition) and participants’ perceived bonding.

Mediating effect of empathy between pain and cooperation

The results showed that neither the direct effect nor indirect of pain on cooperation was significant, direct effect = −.73, SE = .39, 95% CI = [−1.50, .04]; indirect effect = −.004, SE = .19, 95% CI = [−.41, .28].

Mediating effect of bonding between pain and cooperation

The results showed the direct effect of pain on cooperation was significant, direct effect = −.76, SE = .35, 95% CI = [−1.46, −.06]. However, the indirect effect of shared pain on cooperation through participants’ perceived bonding was not significant, indirect effect = .02, SE = .08, 95% CI = [−.10, .23].

Experiment 2

Experiment 1 replicated the findings of BJF. That is, participants in the shared pain condition felt slightly more interpersonal bonding and showed more cooperative behavior than the participants in the shared no-pain condition. Although we can attribute these findings to pain, we can hardly conclude that pain promotes bonding and cooperation in the absence of sharing. To more strictly explore the role of pain and sharing, we conducted a 2 (pain induction: pain vs. no-pain) × 2 (sharing: shared vs. unshared) between-subjects experiment.

Methods

Participants

Power analysis (power = 80%) using G*power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) for an expected medium effect suggested a sample size of at least 90 participants. We recruited 120 subjects from East China Normal University via the same platform we used in experiment 1. One participant voluntarily withdrew from the experiment because she could not withstand the induced pain. Two other participants were not allowed to participate because they were more than three minutes late. The final sample size was 117 (73 females, M age = 20.90 years). The final group sizes ranged between 3 to 4, with a median of 4 and a mean of 3.82. Participants were compensated for their participation.

Procedure

For the shared condition, the participants were randomly allocated to either the pain group (N = 30, eight groups) or the no-pain group (N = 30, eight groups) to complete the experiment as in experiment 1. A group of participants completed the experiment in the same lab. For the unshared condition, however, the participants completed their own tasks in different labs. We randomized participants to either the pain group (N = 27, eight groups) or the no-pain group (N = 30, eight groups). Each person selected one of the four envelopes prepared in advance with different numbers inside. The experimenter led each participant to the specified lab corresponding to the number. Before the economic game, each participant completed the tasks as in experiment 1 alone, without knowing what the other participants were doing. When the economic game began, 4 (3 in some groups) experimenters instructed their subjects in the different labs to perform tasks simultaneously. Each participant reported and wrote down the number they chose. The experimenters exchanged information through WeChat and fed back the smallest number in each trial to their participants. In line with experiment 1, the participants did not know the others’ choices and payoffs. Finally, the participants were debriefed and thanked.

Results

Manipulation check

Participants in the pain condition (M = 7.33, SD = 0.99) reported more intense pain than the participants in the no-pain condition (M = 1.68, SD = 0.75), t(115) = −34.99, p < .001, d = 6.43. Participants also reported greater unpleasantness in the pain condition (M = 6.60, SD = 1.56) than in the no-pain condition (M = 1.77, SD = 0.95), t(115) = −20.40, p < .001, d = 3.74. These results suggested that pain manipulation was effective.

Empathy, Bonding and cooperation

Empathy

A 2 (pain induction: pain vs. no-pain) × 2 (sharing: shared vs. unshared) analysis of variation (ANOVA) test was conducted. The results showed that the significant main effect of pain induction, F(1, 113) = 14.48, p < .001, 95% CI = [−.70, .15], η2p = .11, and sharing, F(1, 113) = 14.48, p < .001, 95% CI = [−.70, .15], η2p = .16. The participants in the pain condition (M = 2.21, SD = 1.05) rated their empathy higher than those in the no-pain condition (M = 1.52, SD = .72) did. The participants in the shared group (M = 2.13, SD = 1.07) rated their empathy higher than those in the unshared group (M = 1.57, SD = .72) did. The interaction effect between pain induction and sharing was significant, F(1, 113) = 23.03, p < .001, 95% CI = [−.70, .15], η2p = .17.

Simple effect analysis showed that participants in the shared condition rated their empathy higher when experiencing pain (M = 2.81, SD = 1.02) than when experiencing no-pain (M = 1.44, SD = .59), t (58) = 6.32, p < .001, 95% CI = [.93, 1.79], d = 1.66. In the unshared condition, however, participants’ empathy rating scores were not significantly affected by pain induction, t(55) = −.17, p = .86, 95% CI = [−.42, .35], d = −.05. Results also showed that participants in the pain condition rated their empathy higher when experiencing pain together (M = 2.81, SD = 1.02) than when experiencing pain individually (M = 1.56, SD =.58), t(55) = 5.59, p < .001, 95% CI = [.80, 1.70], d = 1.51. However, the empathy rating scores of participants in the no-pain condition were not significantly affected by shared experience manipulation, t(58) = −.77, p = .44, 95% CI = [−.52, .23], d = −.20.

Bonding

The 2 × 2 ANOVA test revealed that the main effect of pain induction was not significant, F(1, 113) = 1.65, p = .20, 95% CI = [−.70, .15], η2p = .01. But we did find that the shared experience (M = 3.60, SD = 1.11) increased perceived bonding more than the unshared experience (M = 1.85, SD = 1.22), F(1, 113) = 67.03, p < .001, 95% CI = [1.33, 2.18], η2p = .37. The interaction effect between pain induction and sharing was not significant, F(1, 113) = 1.28, p = .26, η2p = .01.

Cooperation

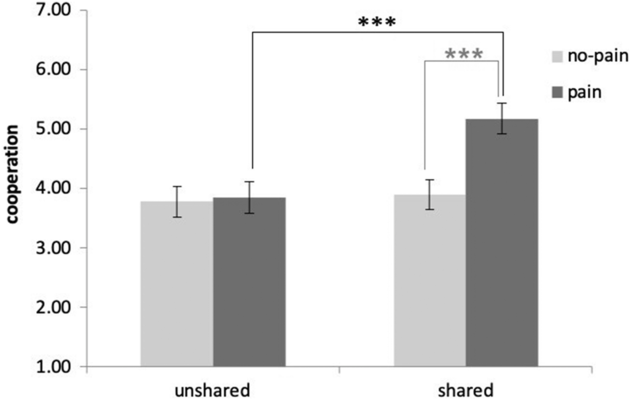

The 2 × 2 ANOVA test revealed the significant main effect of pain induction, F(1, 113) = 6.61, p = .01, 95% CI = [.15, 1.19], η2p = .06, and sharing, F(1,113) = 7.74, p = .006, 95% CI = [.21, 1.24], η2p = .06. The participants in the pain condition (M = 4.55, SD = 1.40) cooperated more than those in the no-pain condition (M = 3.84, SD = 1.54). The participants who completed the pain induction tasks together (M = 4.54, SD = 1.44, 95% CI = [4.18, 4.90]) behaved more cooperatively than the participants who completed the pain induction tasks individually (M = 3.81, SD = 1.51). The interaction effect between pain induction and sharing was significant, F(1, 113) = 5.45, p = .02, η2p = .05.

Simple effect analysis (see Figure 2) showed that participants in the shared condition were more likely to cooperate when experiencing pain (M = 5.18, SD = 1.13) than when experiencing no-pain (M = 3.90, SD = 1.44), t 58) = 3.83, p < .001, 95% CI = [.61, 1.95], d = 1.01. In the unshared condition, however, participants’ cooperative behaviors were not significantly affected by pain manipulation, t(55) = .15, p = .88, 95% CI = [−.75, .87], d = .04. In addition, results also showed that participants in the pain condition cooperated more when experiencing pain together (M = 5.18, SD = 1.13) than when experiencing pain individually (M = 3.85, SD = 1.34), t(55) = 4.15, p < .001, 95% CI = [.68, 1.99], d = 1.12. However, the cooperative behavior of participants in the no-pain condition were not significantly affected by shared experience manipulation, t(58) = .29, p = .77, 95% CI = [−.69, .92], d = .08.

Figure 2. Mean number choices for Experiment 2 as a function of conditions.

Moderated mediating effect analysis

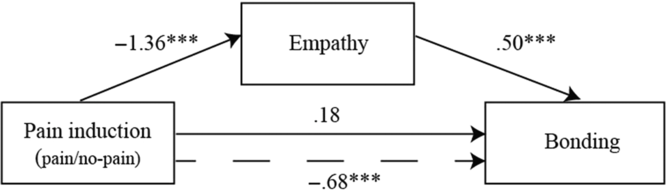

Moderated mediating effect of sharing and empathy on the association between pain and bonding (Figure 3)

The bootstrapping method (5000 bootstrap samples, model 7; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007) was applied. In the shared condition, empathy significantly mediated the relationship between pain and bonding (indirect effect = 1.17, SE = .24, 95% CI = [.72, 1.65]). In contrast, in the unshared condition, empathy did not mediate pain and bonding (indirect effect = −.03, SE = .16, 95% CI = [−.33, .30]).

Figure 3. The moderated mediating effect of sharing and empathy on the association between pain and participants’ perceived bonding.

Moderated mediating effect of sharing and empathy on the association between pain and cooperation

The bootstrapping method (5000 bootstrap samples, model 8; Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007) was applied. The indirect effect of pain on cooperation was not significant through empathy when the pain was shared (indirect effect = −.27, SE = .19, 95% CI = [−.67, .11]) or not (indirect effect = .01, SE = .04, 95% CI = [−.07, .13]).

Moderated mediating effect of sharing and bonding on the association between pain and cooperation

The bootstrapping method (5000 bootstrap samples, model 5; Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007) was applied. Results showed that pain failed to predict cooperation through bonding, indirect effect = −.05, SE = .07, 95% CI = [−.29, .04].

Discussion

We conducted two experiments that reproduced BJF’s findings. More importantly, we further found that pain does promote cooperation, but only when it is shared. When it is not shared, pain does not promote cooperation. These effects are consistent with the view that the social effects of negative experiences depend on the situation (Knight & Eisenkraft, Reference Knight and Eisenkraft2015). At the same time, we found that sharing does promote cooperation, but only when sharing pain rather than sharing no-pain. Moreover, pain does promote cooperation, but only when shared rather than unshared. These results suggested shared pain has a great impact on humans’ cooperation.

Experiment 1 found that the participants who shared pain felt stronger bonding to others and showed more cooperative behavior than those who shared no-pain. These findings are consistent with previous studies that revealed that pain promoted interpersonal trust (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gao, Ma, Zhu and Dong2018), group bonding (Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey, & Leknes, Reference Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey and Leknes2014), and cooperation (Vardy & Atkinson, Reference Vardy and Atkinson2019; Wang, Zhang, Shan, Liu, Yuan, & Li, Reference Wang, Zhang, Shan, Liu, Yuan and Li2019). Experiment 2 provided direct empirical evidence that sharing may be an essential element in developing the bonding and cooperative response to pain. The interaction effect between pain induction and sharing implied that shared pain did promote cooperation but unshared pain did not. These findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that injured people were willing to allocate more money to others when they had witnessed other people’s sufferings than when they had not (Vardy & Atkinson, Reference Vardy and Atkinson2019).

Our study has contributed to the previous research by suggesting that sharing is likely a necessary condition for physical pain to promote cooperation. Some underlying mechanisms may account for this. First, sharing can provide information about similarity. Empathy-induced helping increases with similarity (Preston & de Waal, Reference Preston and de Waal2002). People perceiving similarity are often motivated to feel responsible for prosocial performance (Vollhardt, Reference Vollhardt2009) and at the same time are inclined to project their preferences, attitudes and values onto people with similarities (Ames, Reference Ames2004; Robinson, Keltner, Ward, & Ross, Reference Robinson, Keltner, Ward and Ross1995). The participants who share pain with others tend to believe that the others are as prosocial as themselves and would make the same choices as they do the first time, which is beneficial to cooperative behavior in the weak link coordination exercise. Second, from a social-functioning perspective, the effect of feelings on social behaviors depends on the signal and meaning they convey. In the unshared condition, pain drives self-focus, and the threat it signals to individuals arouses expectations of self-interest and self-survival (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gao, Ma, Zhu and Dong2018). People in distress show more short-sighted behaviors. For example, after natural disasters, people give priority to the motivation to meet short-term needs rather than the motivation to cooperate (Vardy & Atkinson, Reference Vardy and Atkinson2019), and they prefer short-term benefits over long-term benefits (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Han, Ren, Bai, Zheng, Liu and Li2011). However, in the shared condition, people use commonality to clarify group boundaries, and they classify others with commonality as in-group members, especially when previous joint interactions between people are weak or absent (Knight & Eisenkraft, Reference Knight and Eisenkraft2015; Parkinson, Fischer, & Manstead, Reference Parkinson, Fischer and Manstead2005), such as strangers in this study. Pain as a negative external stimulus can signal the potential threat the group encountered, thus motivating people to cooperate to strive for the survival of the group (Knight & Eisenkraft, Reference Knight and Eisenkraft2015). Based on the above, people who share painful experiences are inclined to affiliate with each other, thus paying more attention to the interests of the group and valuing cooperation. Note that the present study mainly focused on pain events; whether other shared negative experiences (e.g., breaking up) promote cooperation requires further investigation. In addition, the valence (positive, negative, and neutral) of the experience may also need consideration in future work.

In our study, we found an interesting mediating effect of empathy. Empathy mediated the association between pain and perceived bonding, and sharing moderated this mediation. In the shared condition, pain increased the perceived bonding by promoting empathy, which is consistent with previous literature (Lamm, Batson, & Decety, Reference Lamm, Batson and Decety2007). Witnessing others’ pain can trigger empathic responses (Abu-Akel, Palgi, Klein, Decety, & Shamey-Tsoory, Reference Abu-Akel, Palgi, Klein, Decety and Shamay-Tsoory2015; Dopierała, Siuda, & Boski, Reference Dopierała, Jankowiak-Siuda and Boski2017). Studies have also shown that even though there are qualitative differences between experiencing pain firsthand and observing others’ pain, there is an overlap in the neurological mechanisms of the two processes to some extent (Lamm et al., Reference Lamm, Batson and Decety2007). People who experience physical pain are more sympathetic and can accept the immoral behaviors of poor people (Xiao, Zhu, & Luo, Reference Xiao, Zhu and Luo2015). The participants in the shared pain condition observed others’ pain and experienced pain firsthand as well, thus generating more sympathetic responses, which have the ability to increase social bonding (Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey, & Leknes, Reference Bastian, Jetten, Hornsey and Leknes2014; Preston & de Waal, Reference Preston and de Waal2002). People with empathy can better understand the inner state of others who suffer from pain (Chopik, O’Brien, & Konrath, Reference Chopik, O’Brien and Konrath2017), which further prompts them to seek social support or build an interpersonal connection to facilitate group survival (Hrdy, Reference Hrdy2009; Rankin, Kramer, & Miller, Reference Rankin, Kramer and Miller2005; Völlm et al., Reference Völlm, Taylor, Richardson, McKie, Deakin, Elliott and Stirling2006). In the unshared condition, however, the mediating role of empathy evaporated. Specifically, the effect of pain on empathy did not exist. The results indicate that the empathy observed in our study is due to the existence of sharing. O’Brien and Ellsworth (Reference O’Brien and Ellsworth2012) have observed similar phenomena. They found that the egocentric projection of somatic feelings only occurred to other people with similar life experiences. When the object was not similar, such projection disappeared. They believed that similarity of suffering might override strong feelings. These moderated mediation findings indicate that it is necessary to consider the effects of sharing when studying the social role of physical pain.

Neither empathy nor participants’ perceived bonding mediated the effect of pain on cooperation. Combining this result with the significant mediating effect of empathy on the association between pain and bonding, we may infer the effect of emotional empathy is strong for bonding, but weak for cooperation. A possible reason may be that cooperation in a social dilemma is a more complex prosocial behaviour that involves numerous emotional and cognitive factors (Pletzer et al., Reference Pletzer, Balliet, Joireman, Kuhlman, Voelpel and Van Lange2018), while bonding mainly contains interpersonal components. Mechanisms behind these findings are worth exploring. Other mediating variables (e.g., trust, social value orientation) on the association between pain and cooperation should be explored in future studies.

It is worth noting that participants in the shared condition completed the cooperation task together, while participants in the unshared condition completed the cooperation task separately. We are not sure whether the results would be different if the participants in the shared condition complete the cooperation task separately, or the participants in the unshared condition complete the cooperation task together. This question requires further investigation in future work.

In sum, our research supports the role of shared pain in promoting prosocial behavior, and clearly confirms that sharing plays a significant role. We conclude that experiencing pain alone does not improve cooperation between strangers. Pain can only function as social glue when it is shared.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (15ZDB121). We are grateful to Brock Bastian for sharing details of his original experiment with us. We thank Tianming Liu and Xinling Li for their work in collecting the data for this research. We also would like to thank Xuesong Shang and Jianghong Du for their help with data analysis, and Qianyun Gao for her constructive suggestions on the earlier version of this manuscript.

Financial support

None.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2020.6