Power is more important than wealth. And why? Simply because national power is a dynamic force by which new productive resources are opened out, and because the forces of production are the tree on which wealth grows, and because the tree which bears the fruit is of greater value than the fruit itself. Power is of more importance than wealth because a nation, by means of power, is enabled not only to open up new productive sources, but to maintain itself in possession of former and of recently acquired wealth, and because the reverse of power – namely, feebleness – leads to the relinquishment of all that we possess, not of acquired wealth alone, but of our powers of production, of our civilization, of our freedom, nay even of our national independence, into the hands of those who surpass us in might…

Friedrich List (Reference List1841, 1909: 37‒38)the continuous, aggressive competition for trade and territory among changing states of unequal size, … made war a driving force in European history.

Tilly (Reference Tilly1992: 54)1. Introduction

Russia's role as a great powerFootnote 1 has included many country-specific factors. Prior to becoming a great power, it was necessary to end Mongol suzerainty, unify the Russian principalities and defend them against numerous Tatar attacks. Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013: 83‒87) argue that the main reason why some countries are poor is that their elites would suffer from the institutions necessary for widespread prosperity. However, traditionally Russia has had relatively low living standards for a different reason. Its rulers have adopted the advice of ListFootnote 2 to prioritize power over wealth. They have given priority to national security, to territorial expansion, to Russia's position on the international stage, rather than to ensuring widespread prosperity. This paper considers the role of Russia-specific institutions, such as the soldiers' cooperative, autocracy and serfdom in the Imperial period, and the Communist Party, economic planning and the state security service, in the Soviet period, in realising its priorities. Parts 1 and 2 provide useful background information for understanding the 2022 Russia-Ukraine war. The conclusions of both Parts are set out at the end of Part 2.

2. The situation in 1815

As a result of the Russian defeat of the French invaders led by Napoleon himself in 1812, the subsequent advance of the Russian army to Paris and the Congress of Vienna (1814‒15) which divided up Europe in the interests of the four victors (UK, Russia, Austria and Prussia), Russia emerged as one of the five European great powers – UK, Russia, Austria, Prussia and France. These powers tried, from 1815, by cooperation among themselves, to preserve the status quo in Europe and maintain the rule of hereditary monarchs. In evolutionary terms, one could say that the outcome of the Franco-Russian war had been to select Russia as one of the recognized great powers.Footnote 3

Modelski (Reference Modelski1996: 332) pointed out that an important assumption made in evolutionary studies of global politics is that of ‘sensitive dependence on initial conditions’ or path dependence. The situation of Russia in 1815 illustrates this. Although 1815 marked a peak of Russian power in Europe, Russia did not suddenly emerge on the great power scene. MuscovyFootnote 4 acquired Kyiv and eastern Ukraine from Poland-Lithuania in the 17th century. The Russian Empire (Peter the Great's name for transformed Muscovy) played an important and growing role in European affairs in the 18th century. Russia defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700‒1721). It briefly occupied Berlin in 1760 and saved Prussia from defeat in the Seven Years War (1756‒63). It was a major player in the partitions of Poland (in 1772, 1793 and 1795) between Russia, Prussia and Austria. It waged successful wars against the Ottoman Empire and expanded its territory to the Black Sea. In 1654 the leader of the Cossacks in Ukraine accepted the Tsar's suzerainty and in 1764 Catherine the Great incorporated much of Ukraine into the Russian Empire. (After the partition of Poland, part of Ukraine was incorporated into the Austrian Empire.). Russia conquered the nomadic peoples of the steppe and the whole of Siberia as far as the Pacific. After various exploration and trading expeditions, it established settlements in Alaska in the 18th century (and settlements in California and Hawaii in the early 19th century). It has been estimated (Fuller, Reference Fuller1992: 86) that just from 1750 to 1791 the Russian Empire grew by about 8.6 million square miles. In addition, it has been estimated that its population grew from 14 million in 1722 to 36 million in 1796. The motivation for this expansion has been much discussed. After surveying the various explanations that have been offered, Fuller (Reference Fuller1992: 175) concluded that Russia's leaders were ‘driven by the desire for security and a lust for geostrategic advantage’.

Russia's emergence as a great power puzzled Enlightenment intellectuals, who wondered how a backward country (which retained serfdom, was ruled by an autocrat and had an underdeveloped economy) could enter the community of ‘civilized Europe’ and play a leading role in it.

What the Enlightenment intellectuals did not realize was that (Fuller, Reference Fuller1992: 83):

The very things that made Russia backward and underdeveloped by comparison with Western Europe – autocracy, serfdom, poverty – could paradoxically translate into armed might. The ruthless application of autocratic power could mobilize the Russian economy for war. The result may not have been a cornucopia of foodstuffs and goods, but it was just enough to sustain protracted war. Similarly, because rural Russia was so unfree it could be tapped for money and most important, for men. It did not matter that the recruits were raw, that rations were short, that equipment was missing. The peasant conscripts were already inured to hardship, and there were more where they came from.

Russia's geopolitical successes up to 1815 showed that, under some conditions, an economically weak country with a large and disciplined army could prosper on the Eurasian and North American geopolitical scenes. One reason for this was that its armies were characterized by a low desertion rate, bravery and endurance. Fuller (Reference Fuller1992: 171‒174) has suggested that this was because of the role of the artels and sub-artels into which the army was divided (an artel was a group of people, usually workers or peasants but in this case soldiers, who worked together to achieve a common goal). The soldier's artel was, in the terminology of North et al. (Reference North, Wallis and Weingast2013: 15), an organization. It can be seen as a cooperative. It functioned as a social unit and also provided material benefits. It facilitated the small-group loyalty on which tenacity under fire depends. It reduced desertion because its members did not want to lose contact with their pals. It created the rules of the game for soldiers which were an important institution in the North et al. sense.

Duffy (Reference Duffy1981: 130) argued that: ‘Signifying far more than the German Kameradschaft, the artel had deep roots in Russian village society, with its peasant meetings and sense of joint enterprise’. In support of this, Duffy cited Klugin (Reference Klugin1861). Keep (Reference Keep1985: 179) was more critical, pointing to two major defects from the point of view of the soldiers' welfare. Furthermore, the esprit de corps generated by the artel might have been generated by barracks were it not for the fact that the Russian army relied on the cheaper method of billeting its soldiers.

Basically, it was the Russian socio-political system that enabled Russia to mobilize large armies. This system included two institutions that were backward, by West European standards, but effective militarily: autocracy and serfdom.

The term ‘autocrat’ for the Muscovite grand prince was introduced from Byzantium by the Orthodox Church at the end of the 15th century. It became part of the grand prince's official title and was used internally at the end of the 16th century (Ostrowski, Reference Ostrowski1998: 177‒178). The word derives from the title autokrator used by the Byzantine emperors. It meant literally a ruler who was not subordinate to another ruler. It came to mean also a ruler who had unlimited power and was not subject to institutional constraints.Footnote 5 The advantages of this system, given the aggressive behaviour of European countries, can be seen by comparing it to the political system in the 16th to 18th centuries in neighbouring Poland.Footnote 6 The autocracy enabled the Russian state to mobilize the economy and population for war. The Polish system was characterized by an elected (by the nobility) king, strict limits on monarchical power and a powerful legislature (controlled by the nobility), the individual members of which could veto majority decisions. This system was unable to implement policies and mobilize resources to defend the country from aggressive neighbours. As a result, in 1795 what remained of Poland was divided up by its neighbours, and it disappeared as a state for 123 years. Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2020) stress the advantages of shackling state power to ensure liberty. They do not stress, although they are aware of, the important fact that shackling the state can limit the state's ability to fulfil a major function – to protect its citizens from hostile countries.Footnote 7 However, they do stress (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2020: Chapter 10) that the shackling of the state in the USA by its constitution has now, and had in the past, a variety of internal adverse consequences.

There has been a long debate about the origin of Russian serfdom. An authoritative interpretation is that of Hellie (Reference Hellie1971). This argued that enserfment was a long process. Its origins can be traced to some limited measures in the second quarter of the 15th century but serfdom for most of the peasantry dates from the end of the 16th century. From that time, peasants were tied to their land, i.e. they were forbidden to move elsewhere. Also corvée became widespread. These measures benefitted the middle service class. Its members held land which had been granted to them in exchange for the obligation to serve in the army (as a mounted force) providing their own horses and weapons, whenever required to do so. (This was similar to the medieval West European fief system.) They formed a significant part of the armed forces of the Muscovite state. Their income came from the peasants who toiled on the land and were obliged to provide for their lords. However, in the 17th century, the gunpowder revolution made this cavalry obsolescent. Nevertheless, serfdom persisted. This was a result of a combination of factors. Serfdom was advantageous for landlords. The autocracy needed serfdom to ensure the support of the landlords. Two major popular uprisings (led by Razin in the 17th century and Pugachev in the 18th) led the government to focus on crushing these uprisings rather than making concessions to the peasantry. Peter the Great's reforms included the restoration of a service class and the payments by the serfs to this class – many of whom were army officers – and the availability of the serfs as soldiers made serfdom an institution useful for the state. It provided both officers and rank and file soldiers.Footnote 8

This combination of institutions, the soldiers' artel, autocracy and serfdom; together with the demographic and geographic situations; and the willingness and ability to employ skilled foreigners, copy new foreign military developments and stimulate the domestic production of new foreign weapons;Footnote 9 together created the conditions for Russia to win wars and emerge as a great power.

3. From the Congress of Vienna to the Crimean War: 1815‒1853

After 1815, Russia used its great power status to play the role, in the words of its critics, of ‘the gendarme of Europe’. It supported hereditary monarchy and opposed liberalism, both internally and externally. Internally, it had to suppress Russians contaminated by Western ideas (e.g. the army officers who staged the failed Decembrist uprising in 1825). It also had to suppress hostile national and religious groups, such as the Poles, who staged an abortive rebellion in 1830‒31, and the North Caucasians who followed the Dagestani imam Shamil in 1834‒59 in his anti-Russian jihad. (Both Poland and the North Caucasus were recently annexed areas with populations that resented Russian occupation.) Externally, it expanded into Transcaucasia up to the Iranian border. This led to a war with Iran in 1826‒27. In 1849 it intervened militarily in Austria to defeat the Hungarian rebels and save the Austrian (subsequently Austro-Hungarian) Empire.

Bad hygiene and poor medical care had huge manpower costs. Morbidity in the army was very high. It has been estimated (Fuller, Reference Fuller1992: 254) that in 1825‒50 ‘only’ 30,000 Russian soldiers died in combat but more than 900,000 died from disease. The extended frontiers and poor communications made concentrating large forces difficult. The efficiency of the army was undermined by corruption.

Between 1815 and 1853 (the year the Crimean War broke out) the relative economic position of Russia worsened as a result of the development of industry in North‒West Europe (in particular, the UK, Belgium and France). Russia lacked the revenue and industry to meet its military aspirations and to keep its armed forces at the technological level of other great powers such as France and the UK.

4. The Crimean War (1853‒56) and its consequences

The Crimean War was fought initially between Russia and Turkey, but France, the UK and Piedmont-Sardinia joined in on the Turkish side. Anglo-French naval squadrons entered the Baltic and destroyed some Russian fortifications but not the main ones at Kronstadt. Russia was victorious in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia. However, the fighting in the Crimea ended up with a defeat for Russia which was forced to abandon Sevastopol after a long siege. The war showed that Russia was able to defeat Turkey, but was militarily inferior to France and the UK. Russia was slow in adopting modern technology. For example, its navy was slow to switch from sail to steam. The rifles and guns of the Franco-British armies were superior to the muskets and guns of the Russian armies, as was the quantity of shells available to the Franco-British armies. The Peace of Paris (1856) which ended the war was regarded as humiliating by the Russian elite. It cast doubt on Russia's position as a great power.

The outcome of the war was a shock to the political and military elite. It was clear that the armed forces had to be reformed. Already in 1856 an adviser to the Tsar on military matters (Dmitrii Milyutin – subsequently Minister of War from 1861 to 1881) proposed a radical change to the recruitment system that required the abolition of serfdom. Five years later, serfdom was abolished. Mid-19th century warfare required large reserve forces that could be called up in an emergency. (Having reserves reduced the cost of the standing army.) Serfdom constrained Russia's ability to maintain a large reserve force.Footnote 10 As Moon (Reference Moon2001: 55) noted: ‘the main reason why serfdom was abolished was the same as the reason why it had been introduced: in the interest of supporting Russia's armed forces’.Footnote 11 Circumstances had changed between the 16th and 19th centuries, but the priority of military factors in Russian decision making remained constant. This corroborates Tilly's (Reference Tilly1992) view of the role of warfare in European history.

5. The danger from Europe and industrialization

The need to catch up with the military prowess of North‒West Europe did not only result in the abolition of serfdom. It also led to a policy of industrialization. Russia needed the means of communication (railways) and resources (coal, steel, engineering) to wage war in Europe (and, with the industrialization of Japan, also in the Far East) on equal terms. Its needs were increased after 1871 when a newly created power in Central Europe – the German Empire – rapidly industrialized. A top-level conference in March 1873 to draw up plans for a possible war with Germany and Austria-Hungary heard a proposal from the Ministry of War for a crash-programme of military railway building to reduce the time taken to mobilize and concentrate the army (as well as plans for building fortifications in Poland). However, these ideas could not be implemented at the time because of opposition by the Minister of Finance (Reutern), who argued that they were unacceptable for financial reasons. Russia's need for effective forces to crush Russian revolutionaries (Tsar Alexander II was assassinated in 1881 by the revolutionary organization People's Will) and national rebellions (there was a revolt in Kazakhstan in 1837‒47 and another Polish uprising in 1863) persisted.

A militarized ListianFootnote 12 industrialization policy was implemented by Count Witte, who was Minister of Finance in 1892‒1903. This policy mainly took the form of: railway construction (most dramatically, the longest railway in the world – the Trans-Siberian); high import tariffs (which both protected domestic industry and generated income for the state); and adoption of the gold standard (in 1897), which reduced interest rates on Russian government bonds, made floating Russian bonds on international markets easier and encouraged foreign direct investment (FDI) in Russia. In the 1890s there was also a rapid expansion of the iron and steel industry in the south of Russia (mainly in the Donbas) as a result of FDI and Russian demand (largely for railway-related products). As a result, by 1900 (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell1994: 47) ‘Russia possessed an integrated iron and steel industry that stood the test of comparison with best practice elsewhere in Europe’. Comparison of Russian labour productivity with British, by sector, in about 1908, shows a wide range (Lychakov, Saprykin, and Vanteeva, Reference Lychakov, Saprykin and Vanteeva2022: 182). In the production of iron and steel tubes Russian labour productivity was 98.6% of the British level and in the production of railway carriages 90.8%. These figures illustrate successes of the industrialization policy. On the other hand, in the production of building materials such as cement and bricks, and in mining, Russia's relative position was much worse. The sector where Russia's relative position was strongest was in the production of spirits. Its labour productivity in that sector was four times that in Britain. This reflected government investment in vodka production, the state monopoly, the high level of demand and the budgetary significance of the sector.

Russia's transformation into a partially industrialized country differed from the Darwinian selection process. This was because of the role of learning, intention, policy formulation and implementation. Attention to the importance of these factors in international politics has been drawn by Rapkin (Reference Rapkin and Thompson2001: 55).

Witte's railway building had not only economic consequences but also military ones. It shortened the time needed for the mobilization and concentration of Russia's armies. This was obviously important in preparing for possible war with Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey. It was also important elsewhere. For example, Witte initiated the Orenburg-Tashkent railway, sometimes known as the Trans-Aral (completed in 1906), that facilitated the transport of Central Asian cotton to Russian textile mills. It also facilitated the rapid movement of troops to Kazakhstan and Central Asia when that was required (e.g. in suppressing the 1916 uprising). He also supported the building and operation of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) through North-Eastern Manchuria. This railway provided the Trans-Siberian with a short cut to Vladivostok (the long route through entirely Russian territory was not completed until 1916). There was also a branch line which ended near Port Arthur, an ice-free Chinese port on the Pacific that Russia virtually annexed in 1898. Witte seems to have thought that expansion into Manchuria would be a profitable business that would provide a market for Russian goods and freight customers for the Trans-Siberian railway.Footnote 13 However, he was also aware of the military and strategic significance of the CER. As he wrote in 1896 (Malozemoff, Reference Malozemoff1958: 75):

On the political and strategic side this railroad will have the importance of offering to Russia the opportunity of transporting her military forces to Vladivostok, at all times and by the shortest route, of concentrating them in Manchuria, on the shores of the Yellow Sea, and in the proximity of the capital of China. Even the possibility of sizable Russian forces appearing in the places mentioned would immensely strengthen the prestige and influence of Russia, not only in China but generally in the Far East, and would contribute to a closer relationship between Russia and the nationalities subject to China.

The Russian occupation of Manchuria in 1900‒1901 and other Russian actions in the Far East provoked the Japanese and led to the Russo-Japanese war (1904‒5) in which Russia was defeated, and in which 400,000 Russian soldiers were killed or wounded.

During Witte's tenure as Finance Minister, the armaments industry was expanded, and by 1900 the proportion of the industrial labour force engaged in military production (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell1994: 37‒38) ‘appears to have been a much higher proportion than in armaments industries elsewhere in Europe’. ‘The cornerstone of the rearmament programme during the 1890s was the re-equipment of the Russian army with the new Mosin rifle’ (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell1994: 43). This was successfully undertaken in 1891‒1901. It required the installation of new machine tools, most of them imported from Britain, France and Sweden. As far as machine guns are concerned, the British firm Vickers agreed to allow the production of its Maxim gun under licence in Russia, and production began in 1904.

However, Witte's industrialization policies, with their stress on heavy industry and neglect of the interests of the landed aristocracy and of the living standards of the peasantry, were widely unpopular and created an urban working class open to revolutionary slogans. When criticized for not increasing the living standards of the population, he explained (von Laue, Reference von Laue1963: 218, 307) that, as a result of threats from more advanced countries, backward Russia had another priority: ‘… at the present time we are in the grip of an iron law which decrees that the requirements of civilization may be satisfied only from what remains after the expenditures for defence have been covered’.

The combined result of the above-mentioned factors, the defeat in the war with Japan (1904‒5) and the influence of liberal and socialist ideas imported from Europe was the abortive revolution of 1905. Russia's agreement to negotiate an end to the war with Japan resulted from: its naval and army defeats; the need to concentrate resources on crushing the internal enemies of the autocracy; and financial difficulties and threat of bankruptcy. Japan's victory in the war led to its recognition as a great power – the first Asian country to achieve that status.

It should be noted that, although between the Crimean War and the First World War Russia was an economically backward country relative to the leading European countries and increasingly the USA, which brought with it serious geopolitical dangers, it became an economically advanced country relative to its southern and eastern neighbours, notably the Ottoman Empire, the Central Asian rulers and China. It took advantage of this by acquiring territory from the Ottomans and China and advancing its frontiers across Central Asia to the borders of Afghanistan. Already in the 18th century the leaders of the Kazakh hordesFootnote 14 accepted Russian suzerainty. From 1822 Kazakhstan was gradually incorporated into the Empire's administrative structures. After that, Russia marched on Central Asia. It conquered the cities of Turkestan and Chimkent in 1864, Tashkent in 1865 and Samarkand in 1868. In 1873 the khanates of Khiva and Bukhara both surrendered and became Russian protectorates. Ashgabat/AshkhabadFootnote 15 was conquered in 1881 and Merv acquired in 1884. Unlike the West European countries which acquired large maritime empires, Russia acquired a large land empire. Its colonies bordered its homeland.Footnote 16

Russian gains on the steppes can be seen as primarily defensive. They ended the danger of raids from the peoples who had attacked Russia since the time of the Mongols. In the 16th century, Muscovy was repeatedly raided by Tatars from the Crimea. In 1571, they successfully attacked Moscow and burned much of it. In 1611‒1617, southern Russia was annually raided by them, and in 1739 a Tatar army from the Crimean khanate attempted to raid southern Russia but was foiled by the Ukrainian line of forts. In 1783 Russia annexed the Crimea. However, there were also economic gains, the acquisition of additional arable land (Ukraine had a large area of good quality soil suitable for arable farming) and mineral resources (e.g. the Donbas coalfield).

Hobson's ‘vent for investments’ theory of imperialism is not relevant to the Russian case. Russia was a net debtor and did not have a surplus of savings. However, it did have a surplus of people. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries (mainly in 1896‒1916), more than 1.5 million peasants from European Russia settled in the Kazakh steppe. This influx of people naturally led to friction between incoming Russian and Ukrainian peasants, and Kazakh pastoral nomads, about land-use rights.

Hobson (Reference Hobson1902: 22) himself recognized that Russian imperialism differed from that of the UK (his main example), France, Germany and the USA. He wrote:

Russia … stands alone in the character of her imperial growth, which differs from other Imperialism[s] in that it has been principally Asiatic in its achievements and has proceeded by direct extension of imperial boundaries, partaking to a larger extent than in the other cases of a regular colonial policy of settlement for purposes of agriculture and industry.

Nor did the Russian case fit into the Leninist development of Hobson's theory. Eighteenth century Russia was not an example of a developed capitalist system, but that did not prevent its rapid territorial expansion.

In 1916, as a response to Tsarist attempts to extend conscription to Kazakhstan and Central Asia, there was an anti-Russian uprising in that part of the Empire.

6. Economic growth and its consequences

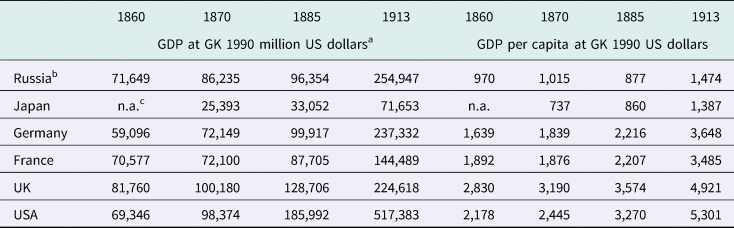

In the post-Emancipation period, the Russian economy grew substantially. From the 1880s industrialization made rapid progress. A major oil industry grew up in Baku; coal-mining was developed in the Donbas; and both light and heavy industry was developed elsewhere, e.g. in Lodz, St Petersburg and Moscow. Between 1885 and 1913 the output of the machine-building industry (this includes transport equipment such as locomotives, agricultural machinery, industrial equipment such as machine tools, electrical products and civilian shipbuilding) increased slightly more than sevenfold (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell1994: 53). Over the whole period 1860‒1913 the average annual growth rate of real GDP has been estimated by Kuboniwa, Nakamura, Kumo and Shida (Reference Kuboniwa2019: 336) as 2.5% and of per capita GDP as 0.9%. Russia's low initial position and rapid population growth meant that in 1913 its per capita national income lagged a long way behind that of its future enemy Germany, and also of its future allies France, the UK and the USA. As Cheremukhin, Golosov, Guriev and Tsyvinski (Reference Cheremukhin, Golosov, Guriev and Tsyvinski2017) have pointed out, in 1913 it was still only partially industrialized. It remained predominantly a country of peasants rather than of industrial workers. Its relative position can be seen from Table 1.

Table 1. GDP of the Russian Empire in an international perspective

a GK 1990 US dollars are Geary-Khamis purchasing-power-parity-based 1990 international US dollars. They are often used for international comparisons.

b These figures are for the Russian Empire, not Russia proper or the Russian Federation.

c Not available.

Source: Kuboniwa, Nakamura, Kumo and Shida (Reference Kuboniwa2019: 346).

The economic growth did not translate into political viability. Many of the growing number of peasants wanted to share out the estates of the nobility. Many of the growing number of workers were dissatisfied with their social, economic and political situation. National and religious minorities (e.g. Poles, Jews, Muslims, Finns, Lithuanians and Georgians) were also dissatisfied. The revolution of 1905 forced the Tsar to agree to civil liberties and an elected parliament (the Duma). The elections to the first Duma (in 1906) produced one very hostile to the government, and for this reason it was soon dissolved. The elections to the second Duma (in 1907) also produced one very hostile to the government which was also soon dissolved. Evidently the Tsar's concessions were inadequate to satisfy either the dissatisfied Russians, or the hostile national and religious groups.

7. The end of the Empire

Russia's defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904‒5 and the abortive revolution it precipitated showed the danger to the stability of the Empire that defeat in war could bring. A state whose survival depended on its armed forces to maintain ‘order’ could not afford a public exhibition of the weakness of those forces. That would just encourage the opposition. The events of 1905‒6 also showed that the army could not always be relied on to use repression against Russians. Repression of Russians was unpopular with many officers, including some top Ministry of War officials (Fuller, Reference Fuller1992: 407). There were numerous mutinies in 1905‒6 of troops unwilling to shoot their own people (Bushnell, Reference Bushnell1985: 100‒108, 204). In addition, a state dependent for its solvency on the influx of foreign capital could not afford the decline in its credit rating that military weakness and revolution could bring. Nevertheless, as a result of its support for Serbia and the priority its leaders gave to maintaining its international prestige, Russia became involved in a war with Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey in 1914.

The Empire collapsed as a result of the combination of pressure from its external and internal enemies. The 1914‒18 war with Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey was prolonged. The Russian army performed well against Turkey and Austria-Hungary and initially fought Germany to a draw (Jones, Reference Jones and Millar2004). However, in the summer of 1915 it fared badly and had to abandon Poland. In 1915‒16 the opposition in the Duma strongly attacked the autocracy.

After two and a half years of war it seemed to much of the population, and in particular to the conscripted peasant-soldiers subjected to military discipline and poor living conditions, that huge numbers had been killed, injured or died from disease for no good reason. Massive discontent was generated by food shortages and rapid inflation (in the second half of 1916, retail prices were about two and half times the level of 1913 and in the first half of 1917 almost four times as much – Gatrell, Reference Gatrell, Broadberry and Harrison2005: 270).Footnote 17 In March 1917, the poor food supplies for both the civilian population and the army, and the rising prices, led to bread riots, demonstrations and strikes in the capital (St PetersburgFootnote 18), and the refusal of some military units to use force to end them. This resulted in the abdication of the Tsar and the end of the Romanov dynasty after more than three centuries in power. This came to be called the February Revolution.Footnote 19 The Russian Empire, which had been one of the great powers in 1914, had ceased to exist (the same fate soon also befell the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and German empires). However, pending the election of a Constituent Assembly, the war continued. Nevertheless, despite the policy of the Provisional Government, in 1917 the army dissolved and could no longer defend Russia.

8. The interregnum 1917‒1922

The Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government in November (new style) 1917 (this was referred to by the Communists as the October Revolution) and closed down the Constituent Assembly in January 1918. They seized power in St Petersburg, Moscow and various other places in the former Empire. They signed an armistice with Germany (and also Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria) in December 1917 and a peace treaty (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) in March 1918. In this they agreed to the loss of: Poland; much of Belarus; Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; and three districts in Transcaucasia that had been conquered from Turkey 40 years earlier; and agreed to make peace with an anti-Bolshevik government in Ukraine. Finland's independence was recognized by the Bolshevik government already in January 1918 (although this did not prevent Bolshevik support for the Finnish Communists in the subsequent Finnish civil war). Bessarabia (which had been acquired in 1812 as a result of the Russian victories in the 1806‒12 Russo-Turkish war) was annexed by Romania in April 1918. In August 1918 the Bolsheviks recognized, in the Treaty of Berlin, the independence of Georgia. Russia lost its chance to acquire control of the entrance to the Black Sea (which had been agreed by the UK and France in the event of a Franco-British-Russian victory in the war). The territorial concessions that the Bolsheviks made in 1918 showed one side of the high cost of military defeat. Another side was the human cost, the deaths and injuries resulting from the war.

During 1918 a new war (known as the Civil War) broke out. This was between rival groups, political (such as the Bolsheviks and the other Russian parties), social (such as white officers, Cossacks, Czech prisoners and the peasants in various areas) and national (such as Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Poles and Central Asians). In addition, foreign countries, such as Germany (till the German Empire collapsedFootnote 20), the UK, France, Japan and the USA, intervened in the general chaos. Ultimately, the Bolsheviks won. They were ruthless, prepared to use violence to achieve their aims; had a substantial number of enthusiastic supporters; supported peasant demands for the redistribution of land and the end of noble land-ownership; and worker demands for control of the factories where they worked and better working conditions; and promised self-determination and the equality of all nationalities in their multinational inheritance, and the end of the oppression of women, Jews and Muslims.

The human cost of the upheavals that began in 1914 and ended in 1922 (World War I, the Civil War, the epidemics of 1918‒20 and the major famine in 1921‒22) was very large. Markevich and Harrison (Reference Markevich and Harrison2011: 679) estimated that in 1914‒23 the number of excess deaths (from wars, disease and starvation) on Soviet interwar territory was 13 million. This huge number excludes excess deaths on territory within the Empire but not within the interwar USSR. The demographic loss of the former Empire would be still greater, since it would include the decline in births and net emigration.

The interregnum ended in 1922. This was marked by two events. First, at an international conference in Genoa in 1922, Russia re-established its status as a sovereign state which was an important player in international affairs, as demonstrated by its treaty with Germany – the Treaty of Rapallo, signed during the conference.Footnote 21 Secondly, in that year a new state came into existence – the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).Footnote 22 This was formally a federation formed by the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR),Footnote 23 the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Actually, it was a unitary state ruled by the Communist party (the name of the former Bolshevik party from 1918). The USSR was the largest and most important of the successor states of the Russian Empire. Others were Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

A key institution in the USSR was the Communist Party. This created the state, played the decisive role in determining state policy, played an important role in implementing state policy, carried out official propaganda, formulated the state ideology, controlled personnel policy and had a large membership. It had important economic roles at the local level in implementing state policy and in coordinating the various bureaucratic agencies. Its leader was the dictator of the USSR.

9. First steps of the USSR: 1923‒29

In 1923‒29 the USSR strove to overcome the devastation of the 1914‒22 period and reach the economic level of the Russian Empire. After the end of the Civil War, the Red Army was demobilized. The USSR's internal politics were marked by a strengthening of the dictatorship and by the internal divisions in the Communist Party, which led to the rule of an oligarchic group led by Stalin. Its economy was marked by recovery. In international affairs it planned for possible wars with Poland and Romania (and standing behind them France and the UK) and cooperated with Germany in evading the restrictions imposed on Germany's armed forces by the Treaty of Versailles. The USSR had an advantage in international affairs denied to the Russian Empire: the soft power provided by its ideology. The USSR used this soft power to create the Communist International, usually known as the Comintern (the organization of the world's Communist parties, headquartered in Moscow and dominated by the Soviet party). The Comintern directed the foreign Communist parties, and used them to influence domestic politics in many countries in ways thought useful to the USSR. Its ideology also gained it sympathy and support among left-wing people and organizations throughout the world. This helped it to recruit spies for the USSR. However, the ideology also created foreign enemies strongly opposed to Communism and the USSR.

Russia experienced hyperinflation in 1918‒22. This resulted from the need to finance the Civil War under conditions of economic collapse. However, in 1921 the Communist Party switched from requisitioning food from the peasants to a tax, at first in kind and then in money (the key measure of the New Economic Policy or NEP). It also permitted small-scale private enterprise, while retaining the commanding heights of the economy (the banking system, the railways and large-scale industry) in state hands. In 1922‒25 the currency was stabilized. Gradually the economy recovered.

However, there was a major, unforeseen, problem. In 1927, 1928 and 1929 it proved very difficult for the state procurement agencies to buy adequate grain from the peasants to feed the towns and the army and to provide a substantial volume of exports (before the First World War Russia's main export product was grain). This problem mainly resulted from two causes. They were the ‘goods famine’ and price policy. The ‘goods famine’ was the shortages of goods (e.g. consumer goods and tools for agriculture) that the peasants wanted to buy. During the 1920s the Communist Party created (unintentionally) a shortage economy.Footnote 24 This naturally reduced the attraction for the peasants to sell grain, since the goods they would have liked to buy with the proceeds were often unavailable. The goods famine was worsened in 1927 by the war scare of that year which led to widespread hoarding (Velikanova, Reference Velikanova2013: 86‒88). The grain problem also partly resulted from the Communist Party's price policy. Keen to appear as a supporter of the interests of the workers, the Party strove to keep the price of bread (the main wage good) low. To achieve this, it attempted to hold procurement prices for grain low. Low prices naturally were unattractive for the peasants who grew the grain. Hence, instead of selling their grain to state procurement agencies at low state prices, they used it as food for their own families, as fodder for their animals or for sale to private traders. A subsidiary cause of the grain problem was an ideology that imagined a class war was going on in the countryside and that harsh measures were needed to restrict the activities of successful peasants or traders. Another was a statistical fog which made it difficult to determine what the real situation was with respect to the peasants and grain supplies.

The resulting shortages of bread (for domestic consumption) and of grain (for export) were increasing problems for the state. To reduce discontent among the workers, bread rationing was introduced in many cities in 1927 and 1928, became general in 1929 and persisted till 1935.Footnote 25 The shortage of grain for export made the import of technology from North America and Europe very difficult (because of the resulting shortage of money to pay for it). Without solving the grain problem it was impossible to realize the government's ambitious industrialization plans. In January‒February 1928 Stalin himself visited Siberia to investigate the reasons for the poor grain procurements. He increased procurements by using Civil War methods: searching the villages for grain, requisitioning it and making arrests. He blamed the problems on the evil ‘kulaks’Footnote 26 who were allegedly undermining Soviet (i.e. Communist) power.

In 1929, Stalin announced the policy of ‘liquidating the kulaks as a class’ and mass collectivization began in early 1930. Its purposes were to solve the grain problem by the application of modern American technology, such as tractors and combine harvesters, on large farms (Nefedov, Reference Nefedov2017: chs 5.1, 6.1; Tauger, Reference Tauger, Trentmann and Just2006), and to adapt the economy to potential future war conditions (Simonov, Reference Simonov1996: 67). These policies led to a prolonged violent conflict between the state and the peasantry and herders.

A major outcome of this conflict was the famine which peaked in 1933. It seems that the population at the beginning of 1935 was about 18 million less than it would have been if the NEP had been continued (Nefedov, Reference Nefedov2017: 351). About two-thirds of this enormous population loss was a result of the decline in the birth rate.

In this conflict Team-Stalin was victorious. It established state control over the production and distribution of grain. It and its successors maintained that control for decades…The victory of Team-Stalin removed one major obstacle (bread shortages) to the policies of industrialisation and war preparations, reduced another one (the shortage of grain for export) and ensured abundant labour for the new factories and construction sites (Nefedov and Ellman, Reference Nefedov and Ellman2019: 1063‒1064).

10. Pre-war planning: 1930‒41

The public face of the ambitious industrialization plans of the Soviet government was exhibited in a series of five-year plans, beginning with the First Five-Year Plan (1928‒32). They had an enormous impact on the rest of the world. It seemed to many that the capitalist system, which had led to the catastrophic Great Depression, should be replaced by a superior system – a planned economy. In 1933, as part of the New Deal, the USA established its own National Planning Board, renamed National Resources Planning Board in 1939 (Clawson, Reference Clawson1981). In 1933 Mexico's ruling party adopted a Six-Year Plan. In 1936 Poland and Germany both adopted Four-Year Plans. In 1936 China adopted a Three-Year Plan. After World War II many more countries adopted national economic plans. All of these plans resulted from positive impressions of Soviet planning.

A major objective of Soviet planning was military modernization, i.e. preparation for war (Kontorovich, Reference Kontorovich2019; Samuelson, Reference Samuelson2000a, Reference Samuelson, Barber and Harrison2000b). The Soviet leadership shared the view of 19th century Japanese leaders that, in the absence of economic and military modernization, the country would be meat for predatory countries. This was also the view of the Chinese official Feng Guifen. In his Dissenting views written in 1861, he wrote that, without economic and military modernization, ‘We Chinese will be meat and fish for the hundred other nations of the world’ (Schell and Delury, Reference Schell and DeLury2013: 51). This 19th century Japanese-Chinese fear of foreign predators was also an important part of the motivation for Soviet economic policy in the 1930s. This was explained by Stalin in a famous speech of 1931 (Stalin, Reference Stalin1955: 40‒1).

The Communists had learned from World War I that modern warfare required vast quantities of modern weapons. Hence preparations for an industrial war were essential. This explains the stress in Soviet plans on heavy industry and also why some of the new plants of the First Five-Year Plan (and later) were dual purpose plants that produced civilian products in peacetime but could be quickly shifted to military production. One example of the latter is the Stalingrad Tractor factory that was designed in such a way that it could be quickly switched to producing tanks. Another example is the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant that produced 18,000 tanks during the Soviet-German war. In 1932, the USSR, which a few years earlier had been incapable of producing any tanks, produced 2,600 of them. As the former Soviet military intelligence officer Vitaly Shlykov pointed out (Samuelson, Reference Samuelson2000a: xiii): ‘between 1932 and the second half of the 1930s the USSR produced more tanks and [military] aircraft than the whole of the rest of the world’.

The orientation of Soviet planning to war preparations is clear from the views of US engineers engaged in building the major plants of the First Five-Year Plan (Melnikova-Raich, Reference Melnikova-Raich2010), contemporary official documents and the reaction of foreign governments. The resolution on the Five-Year Plan approved by the Fifteenth Party Congress (1927) stated that (Pyatnadtsatyi s”ezd, Reference Pyatnadtsatyi s”ezd1962: 1442):

In view of a possible military attack by capitalist states against the proletarian state, the Five-Year Plan should devote maximum attention to the fastest possible development of those sectors of the economy in general, and of industry in particular, which play the main role in securing the country's defence and in providing economic stability in wartime.

The Soviet Communist Party had learned an important lesson from the defeat of Russia in World War I. In preparing for that war (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell1994: 300), ‘… military planners gave no thought to the questions of industrial mobilization’.Footnote 27 In retrospect this seemed a major mistake of the Tsarist regime which the Soviet state was determined not to repeat.Footnote 28 As Stone (Reference Stone2000: 19) has noted:

The lessons of World War I, that victory [in major wars] required comprehensive peacetime organization and planning, were the same for all. What distinguished the Soviet Union, far ahead of the pack in 1933 in the extent of its militarization, was not so much the presence of any particular factor but the absence of any effective checks on militarization… the social and political nature of Stalinism eliminated forces pushing against untrammelled militarization, allowing Bolshevik ideology, intellectual consensus on the need for military control over the civilian economy, genuine but exaggerated foreign threats, and military desires to produce the complete militarization of the Soviet economy.

In July 1931, the Japanese Military attaché in Moscow reported to a visiting general from the Japanese General Staff that (Khaustov et al., Reference Khaustov, Naumov and Plotnikova2003: 292‒293):

At the present time, the USSR is energetically implementing the Five-Year Plan for the construction of socialism … Heavy industry occupies a central place in this plan, in particular those branches of industry which are connected with increasing the defence capacity of the country … The basic goal of the Five-Year Plan is to increase military strength.

The idea of using planning to prepare for war spread to other countries. The Chinese Three-Year Plan adopted in 1936 (Kirby, Reference Kirby1990: 127):

… committed the Chinese government to military-industrial development in preparation for an expected war. This plan could by no means be considered an overall blueprint for national development. But as a soberly conceived design for state-led industrial development closely linked to the regime's military-political strategy, feasible within the context of available resources and innovative in attracting foreign technical assistance through barter and counter-trading mechanisms, it set a new standard for government plans.

Another country whose planning, like that of the USSR in the 1930s, was mainly devoted to the needs of the military sector was Nazi Germany. After comparing Soviet and Nazi economic planning in the 1930s, Temin (Reference Temin1991: 592) concluded that: ‘Socialist planning in both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the 1930s was primarily a means for military preparation and mobilisation’.

However, the Marxist idea of economic planning as a rational economic system, much more efficient than the anarchy of production under capitalism, remained alive throughout the world. It gained strength from Soviet economic growth, rapid industrialization and perceptions of Soviet achievements in education, science, the abolition of unemployment, security of employment and medical care for the entire population. After World War II, this led to the voluntary adoption of a non-military version of economic planning in countries such as France, the Netherlands and UK,Footnote 29 and in developing countries such as India. All of these experiments were a result of positive perceptions of the Soviet experience and became very unfashionable after the collapse of the USSR. They illustrate the importance of the worldwide soft power which the Soviet experiment exercised for decades.

Soviet industrial output in 1928‒41 grew rapidly. According to Khanin (Reference Khanin1991: 146), industrial production in this period grew by 10.9% p.a. This was an impressive performance. It was largely based on the import of technology, mainly from the USA and Germany. As Khanin (Reference Khanin1991: 180) noted: ‘… in the prewar period foreign sources provided at least 50% of the machinery needed by industry and during the First Five-Year Plan this figure increased to 75‒80%’. Hence Soviet industrial growth in 1928‒41 can be considered an example of what later came to be called ‘import-led growth’ (Gomulka, Reference Gomulka1978; Gomulka and Sylwestrowicz, Reference Gomulka, Sylwestrowicz, Altmann, Kyn and Wagener1976; Hanson, Reference Hanson1981: 204).Footnote 30 Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013: 92) explain the USSR's economic growth from 1928 to the 1970s, despite its lack of inclusive institutions and free markets, by its ability to move resources from agriculture to industry. This is a very partial explanation which entirely neglects the role of the import of technology. Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013: 127) also assert that Soviet economic growth in 1928‒60 ‘was not created by technological change’ despite substantial Soviet technological change, much of it imported from abroad.Footnote 31 However, they are correct to draw attention to the contribution of the increased industrial labour force and investment as sources of Soviet growth.

The development of the economy in an international perspective can be seen from Table 2.

Table 2. GDP per head of the USSR in international perspective

a $INT are ‘international’ dollars in the meaning of Phase IV of the International Comparison Project.

Source: Davies, Harrison and Wheatcroft . (eds.) (Reference Davies, Harrison and Wheatcroft1994: 270).

Table 2 shows that in both 1928 and 1940 the USSR was the poorest of the great powers, measured by GDP per person. It also shows that in this period it had the fastest rate of growth. However, high rates of growth of GDP per head did not mean fast rates of growth of personal consumption. The three countries with the highest growth rates were either engaged in major armaments programmes (the USSR and Germany, which were engaged in an arms race from 1936) or actually engaged in war (Japan, which was fighting a war with China). Hence their increased output was not available for consumption.

Partly in preparation for the anticipated coming war, in 1937‒38 about 1.7 million people (many of whom were perceived as potential fifth columnistsFootnote 32) were arrested by the NKVD (the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs). Of these, at least 725,000 were shot, and nearly all the remainder sent to the Gulag or other places of detention (Danilov, Reference Danilov2006: 568).Footnote 33

Another example of war preparations and of their costs for the population concerns labour regulations. In 1940 labour legislation was made stricter (e.g. workers were forbidden to leave their jobs voluntarily, i.e. they were tied to their factories like serfs to their fields). Absence from work became a criminal offence, and being more than 20 minutes late for work was treated as absenteeism. The working week was increased from five 7-hour days and one day off every six days, to six 8-hour days every seven days (an increase of 18%).

The economic institutions introduced in the USSR in the early 1930s were successful in preparing the country for war. By the outbreak of war, national economic planning had produced large quantities of weapons and created the capacity to produce many more. Even the collective and state farms, despite their defects, can be seen as successful institutions. They provided grain for export and facilitated the rationing system in the early 1930s and during the war.Footnote 34 These new institutions played a major part in the defeat of the Nazis. Davies, Harrison, Khlevniuk and Wheatcroft (Reference Davies, Harrison, Khlevniuk and Wheatcroft2018: 336) pointed out that:

Measured against civilian criteria of productivity and prosperity, the Soviet economy of the 1930s failed. Measured against benchmarks of national capability, such as military power, it looks far more successful. A distinctive and enduring feature of the Soviet economy was its capacity to support military power out of proportion to its level of development.

Another important Soviet institution was its state security service (Cheka-OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD-KGB). This played a key role in implementing collectivization, provided the leadership with information about what was happening in the country and provided (forced) labour for many economic projects. Its activities ensured socio-political stability despite the difficulties of everyday life and state terror. Fear of it increased acceptance of the Soviet system. A striking post-war example of the significance of the state security service is its role in the Soviet atom bomb project (Ellman, Reference Ellman2008: 101). Information in foreign countries about the state security service, its trials, arrests, tortures, killings, espionage and Gulag greatly reduced the soft power of the Soviet experiment.

Developments from 1941 are analysed in Part 2. The Conclusion of both Parts is at the end of Part 2.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to P. Ellman, J. Cooper, P. Hanson, M. Harrison, S. Hedlund, V. Kontorovich, P. Vries and the editors and referees of this journal for helpful comments on the draft. The usual caveat applies.