In 1928, the German Nazi Party earned just over 2 percent of the votes in the general federal elections. By mid-1932, it had received 38 percent of votes in the national elections, becoming the largest political party in the Reichstag. How did this shift to the extreme far-right happen so quickly? Economic factors, such as high unemployment associated with the Great Depression, sociocultural issues, and the excessively punitive Treaty of Versailles, are well studied. They undoubtedly played an important role in the rise of the Nazi Party. Still, the rapid growth of support for the Nazi Party well into the Great Depression remains the subject of considerable debate (Eichengreen 2018; Ferguson Reference Ferguson1996; James Reference James1986; Satayanth et al. 2017; Temin 1990; Voth 2020).

In this paper, we investigate the association between the austerity measures implemented by the German government between 1930 and 1932 and voters’ increased support for the Nazi Party. A growing literature studies the interactions between political preferences and fiscal policy with evidence that austerity packages are correlated with rising extremism (Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi 2019; Bor Reference Bor2017; Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2015, 2018; Fetzer Reference Fetzer2019; Ponticelli and Voth 2020). It stands to reason that the austerity measures implemented in Germany in the early 1930s played a role. However, we are aware of no direct quantitative assessment of this issue for the Weimar Republic.

During this period, Heinrich Brüning of the Center Party, and Germany’s chancellor between March 1930 and May 1932, implemented a set of measures via executive decree in order to balance the country’s finances. These austerity measures included real cuts in spending and transfers as well as higher tax rates. Brüning believed that the consequent suffering would be highly visible, thereby eliciting international sympathy for the Germans and helping put an end to the unpopular reparations imposed at Versailles (Evans Reference Evans2003).

To test the hypothesis that austerity can explain increased Nazi vote share, we use city and district-level election returns for the federal elections of 1930, 1932 (July and November), and 1933. We then link local vote shares to different proxies for city, district, and state-level fiscal policy changes while also controlling for other potential explanations for the rise of the Nazis, such as unemployment, changes in wages, and economic output. Our results are robust to inclusion of a number of different controls and specifications including city-level time trends, state by year fixed effects, and electoral district by year fixed effects.

The observational data we use to study austerity and extremism have a number of features that enable us to overcome obvious issues of reverse causality and endogeneity. Brüning’s policies on spending and taxes were not expected. Instead, they became an outcome of the unexpectedly severe economic and financial crisis. They were decided at the Reich level by Brüning and his cabinet with implicit support of the Reichstag. Spending cuts and tax increases were uniformly applied across the nation so that the policy decisions were exogenous to the preferences of specific cities and districts. As noted by Balderston (Reference Balderston1993, p. 225), “the progressive ‘nationalization’ of taxing and spending decisions, justifies historians in the responsibility they place on the Brüning cabinet and on Brüning personally, for the fiscal balance during the slump.”

Limits on spending and on changes to taxes, policy variables often formerly controlled by local authorities, were also imposed. Successive pay cuts to national civil service salaries are an example. Although some expenditure cuts were out of the hands of localities and mandated by the national government, some budget categories were hit harder than others. This fact means that nationally imposed budget cuts might have differential impacts on localities depending on the predetermined patterns of spending and reliance on the national government for transfers to fund different categories of spending. We use city-level variation in the preausterity reliance on Reich transfers and national changes in transfers as a shift-share instrumental variable for subsequent spending declines. Since states, localities, and the central government were unable to borrow on international capital markets after 1930 (Schuker Reference Schuker1988), localities were forced by markets to traverse the depression with highly disruptive fiscal shocks.

As for taxes, a similar logic applies. The Reich maintained control over a number of specific taxes, determining, for example, the statutory marginal rates for income taxes and corporation turnover taxes. Changes to the statutory marginal rates applied equally and evenly to all states and localities, but lower brackets had higher percentage increases in income tax rates (Newcomer Reference Newcomer1936). We use variation at the local level in the initial distribution of taxable income across tax brackets and national changes in tax policy to instrument for the austerity-driven tax hikes. To make identification valid, we need to avoid confounding our fiscal shock with an unobservable economic shock correlated with income distribution. On the income distribution, Dell (Reference Dell, Anthony and Thomas2007) and Gómez-León and de Jong (Reference Gómez-León and de Jong2019) show that Gini coefficients and top income shares were fairly constant between 1928 and 1933.

Higher Nazi vote share could be because of resentment arising from distributional battles for slices of the fiscal pie in difficult times. There is clearly a distributional component to these changes, the percentage rise in tax rates being much higher for the lower income brackets. Wueller (Reference Wueller1933) also discusses that while tax revenue had traditionally been retained where it was collected, intrastate redistribution was increasingly becoming need based during the Depression.

We also use a number of different econometric specifications to eliminate further concerns about endogeneity. We employ both city/district fixed effects models and long differences to focus on within-locality variation in Nazi support. We are also able to circumscribe the control group by matching districts to neighboring districts just across state borders, as in Dube, Lester, and Reich (2010). While relevant observables were spatially smooth, fiscal policy across the state borders was sharply different because state policies responded to statewide concerns. With this identification strategy, we are also able to control for common economic shocks correlated with the initial characteristics of localities by using period by district-pair fixed effect interaction terms. Even after controlling for local economic shocks between 1930 and 1932 in this way, austerity remains a statistically, economically, and politically significant determinant of Nazi vote share.

We also provide some novel quantitative estimates concerning the channels by which austerity mattered. To do so, we study the relationship between mortality rates and austerity. We find a plausible link, since where public spending on health care dropped more, mortality was higher. These places also saw a relatively large increase in Nazi support at the polls. Finally, looking at archival documents of Nazi propaganda, we document how Nazi leaders invoked austerity to attack Brüning and the Weimar Republic and how Brüning’s tax rises were seen as inefficient and unfair by the German masses.

Even though there has been a German debate on whether there was an alternative to austerity (Borchardt Reference Borchardt, Karl Dietrich and Hagen1980; Büttner Reference Büttner1989; Ritschl Reference Ritschl1998; Voth 1993) and speculation that austerity played a role in the rise of the Nazi Party, to our knowledge, no previous research has directly tested the quantitative impact and the channels by which fiscal austerity mattered. Falter, Lindenberger, and Schumann (1986), Frey and Weck (1981), King et al. (2008), and Stögbauer and Komlos (2004) studied the economic shocks of the period, but they did not use fiscal data and the transmission mechanisms emphasized are different from ours. Previous work focused on a direct channel from lower disposable incomes and unemployment to frustration at the polls. On global comparisons, one study evaluated the impact of the Great Depression and austerity on voting patterns in 171 elections in 28 countries (Bromhead, Eichengreen, and O’Rourke 2013) and another looked at the European level (Ponticelli and Voth 2020). Yet, these have not considered the particular context of Weimar Germany.

Regarding the connection between political competition and differential effects of the crisis, the literature notes that the lowest status groups and the unemployed turned to the Communists (Falter, Lindenberger, and Schumann 1986; King et al. 2008) but those just above in the economic hierarchy, who had more to lose from the tax hikes and spending cuts, seemed to favor the Nazis. Between 1930 and 1933 the Nazis gained votes from all walks of life. Yet, Evans (Reference Evans2003), Falter, Lindenberger, and Schumann (1986), King et al. (2008), and Voigtländer and Voth (2019) have documented how the party was “underrepresented” among the working classes, in industrial cities, and in Catholic regions. We control for these fixed factors and allow for interactions between them and our measures of austerity.

Our baseline results show that Brüning’s austerity had a sizable effect. Each one-standard-deviation increase in austerity was associated with between one quarter to one half of one standard deviation of the dependent variable. In localities where austerity was more severe, Nazi vote share was significantly higher. Our novel use of within-locality variation in the size of the fiscal shock sheds light on the local and national experience of democratic decline.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we provide a detailed account of the main existing explanations for the rise of the Nazis. The third and fourth sections, respectively, review how austerity was implemented and present the historical context of the different elections in Germany between 1930 and 1933. In the fifth and sixth sections, we show our main results and robustness checks for the city- and district-level outcomes using spending and tax data. The final section concludes.

COMPETING EXPLANATIONS

There are many competing explanations for the stark rise of the Nazi Party in Weimar Germany. The conventional explanation is the impact of the Great Depression. Those hit hardest by the economic downturn held the incumbent parties responsible for their situation, punishing them by voting for the Nazi Party. Economic activity peaked in Germany in 1928, driven by a sharp downturn in investment (Ritschl 2002; Temin Reference Temin1971). Later, the cessation of capital inflows and a crisis in the German banking sector culminated in a slowdown in the growth of credit, while other international shocks prolonged the downturn. Yet, the unwillingness of the Reichsbank to stop the deflation mattered but cannot necessarily explain regional variation in Nazi support.

A similar point could be made with respect to the increasing numbers of unemployed workers, soaring from 1.4 million in 1928 to 5.6 million in 1932. Unemployment also reached very high levels in other countries, such as the United States, around that time, without being accompanied by electoral radicalization (Eichengreen and Hatton 1988). Additionally, the unemployed were more likely to vote for the Communist Party or the Social Democrats (in Protestant precincts) rather than the Nazi Party (Evans Reference Evans2003; King et al. 2008), as the Communist Party was perceived as the party that traditionally represented workers’ interests.

A third explanation invokes resentment about high debt repayments imposed on Germany in the Treaty of Versailles. These debts initially totaled up to 260 percent of 1913 GDP (Ferguson 1997; Ritschl 2013). Although France and Britain had war debt burdens similar to Germany, the Versailles agreements treated Germany as a conquered enemy, forcing it to pay a large share of the allies’ costs of the war. This placed financial demands on Germany that were very difficult to meet and that were dubbed as “cruel” by some (Keynes Reference Keynes1920; Temin and Vines 2014). However, Germany’s war debts were never completely paid (Galofré-Vilà et al. 2019). German war debts were postponed in the Hoover moratorium of 1931 or temporarily suspended in the Lausanne Conference a year later.Footnote 1

Fiscal austerity might simply have been a driver of economic collapse if multipliers were large enough, but Ritschl (2013) reports that these were small. If austerity mattered, it must have been something about the unique way Germany experienced it. Even if austerity did not have a contractionary effect on aggregate demand, it still might have had distributional consequences that, in turn, affected how people voted. Austerity not only hurt the lower middle classes and elites, by increasing tax rates on profits and income, but ostensibly also had a major impact on people’s welfare by cutting key social spending lines after 1929. Brüning was commonly known as the “Hunger Chancellor,” stressing how these budget cuts threatened living conditions. There is, in fact, some qualitative consensus on Brüning’s devastating legacy. Feinstein, Temin, and Toniolo (2008, p. 90) opine that “Brüning introduced a succession of austerity decrees. The descent was cumulative and catastrophic.” Several authors also noted that austerity could have contributed to political extremism. For instance, Feldman (Reference Feldman2005, p. 494) comments that “Brüning’s reliance on emergency decrees had paved the way for a right-wing rule” and Eichengreen (Reference Eichengreen2015, p. 139) that “Brüning’s unrelenting austerity, by plunging the economy deeper into recession, increased political polarization.”

Hitler also viewed austerity as a springboard to power. Twelve days after Brüning enacted his fourth and last emergency decree, Hitler issued a mass pamphlet titled The Great Illusion of the Last Emergency Decree. He concluded the letter saying that “Although that was not the intention, this emergency decree will help my party to victory, and therefore put an end to the illusions of the present system.” There are also attacks on Brüning’s cabinet on earlier fiscal plans. For instance, in October 1931, Hitler wrote an Open Letter from Adolf Hitler to the Reich Chancellor in which he asked, “Where has the hereby-reduced number of unemployed been left? Where are the successes of the ‘rescue of agriculture’? And when, Mister Chancellor Brüning, did the then-promised reduction of taxes finally begin?”

These pamphlets also made promises to relax the budget constraint if the Nazis were elected. For instance, on May 1932, a pamphlet titled Emergency Economic Program of the NSDAP offered “fundamental improvements in agriculture in general, multiple years of taxation exemption for the settlers, cheap loans and the creation of markets by improving transportation routes, and making them less expensive.” On the welfare system, “National Socialism will do all it can to maintain the social insurance system, which has been driven to collapse by the present System.”Footnote 2

AUSTERITY AND THE GERMAN ELECTIONS

In March 1930, Brüning was appointed as German Chancellor by President von Hindenburg and fiscal reforms were quickly implemented, with a first austerity plan in July 1930. Austerity was implemented by emergency decree under Article 48 of the constitution, with the Reichstag eventually consenting without formal debate. From its beginning, austerity was highly unpopular, leading von Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag and call new elections.Footnote 3

In the elections of September 1930, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the political home of the worker movement, remained as the largest party in the Reichstag (yet, moving from 29.8 percent of the total votes in May 1928 to 24.5 percent in 1930). The Center Party, which was Brüning’s party, also started to lose popularity (moving from 12.1 to 11.8 percent), and the Communist Party, the main party of protest for those workers disenchanted by the Weimar regime, somewhat managed to collect new votes (moving from 10.6 to 13.1 percent). The German National People’s Party (DNVP), a bourgeois, xenophobic far-right party that shared many of the Nazi’s extremist views, declined from 14.2 percent of total votes to 7 percent. Above all these changes, support of the Nazi Party surged from almost no support to more than 6 million voters (moving from less than 3 percent to 18.3 percent).

Although austerity was only implemented some months in advance, the September 1930 election was a key turning point in German history because it was seen as a withering verdict against austerity—a message that went unheeded. As discussed by Temin (1990, p. 82), “…it is clear that the vote of 1930 was a resounding rejection of Brüning’s policies at an early stage.” Initially, only the Nazis (and, to some extent, the Communists) campaigned against austerity, with the DNVP struggling to find a coherent response on the austerity front. For instance, Fulda (Reference Fulda2009, p. 158) noted that for the first emergency decree, “the parliamentary DNVP was split: while Hugenberg’s followers voted against it, the group around Westarp decided to support it.” He also comments that when “the tension between the pro-Brüning DNVP parliamentarians around Westarp and Hugenberg’s supporters increased… Goebbels noted in his diary that the DNVP was ‘finished’: ‘All grist to our mill.’”Footnote 4 As for the SPD, Brüning’s memoirs highlight that he often turned to members of the SPD for support. Successive emergency decrees in June 1931, October 1931, and December 1931 raised nearly all of the main taxes controlled by the Reich (income, wage, turnover, excise duties, tariffs), put limits on spending, introduced exclusions from unemployment and relief benefits, and mandated civil service pay cuts (over 50 percent of the state-level spending bill according to Balderston (Reference Balderston1993)).

By the end of May 1932, Brüning was removed from the Chancellorship and was replaced by von Papen. The elections of July 1932 boosted Nazi popularity even more, achieving 37.3 percent of the votes. Yet, the Nazis lacked an overall majority at the Reichstag and von Papen continued as Chancellor. In the second half of 1932, von Papen signaled the end of austerity and started to introduce some stimulus packages, involving employment programs, tax credits, and subsidies for new employment and public works projects (Evans Reference Evans2003; Feinstein, Temin, and Toniolo 2008). Despite the fact that any short-lived effect was modest in magnitude compared to the cumulative effect of Brüning’s austerity, the easing of austerity, along with the ostensible cancellation of war debts at the Lausanne conference and an improved economic environment,Footnote 5 coincided with a decline in Nazi vote share in the elections of November 1932 (collecting 33.1 percent of the votes). As O’Rourke (Reference O’Rourke2010) comments, “by this stage Brüning was gone, his successor adopted some modestly stimulative policies, and there were signs of a partial recovery. Not coincidentally, in November 1932 the Nazi share dipped to 33.1 percent; but by then it was too late, and the Weimar Republic was doomed.”

Von Papen had virtually no support in the Reichstag, and in an ill-fated attempt to increase his support, he called for new elections in November of 1932. Yet, given mass discontent and social instabilities, later on, Hindenburg appointed Schleicher of the DNVP as Chancellor.Footnote 6 He lasted for less than two months. Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor on 30 January ahead of the decisive elections of March 1933, where the Nazi Party became the largest party (with 44 percent of the votes) and built a bare working majority with the DNVP that offered 8 percent of the votes.Footnote 7 These were the last elections of the Weimar Republic and were tarnished by violence and intimidation and might not be regarded as free and democratic.

Under Brüning’s mandate, there was a process of centralizing fiscal policy and the national government began to limit the ability of states to raise tax rates as well limited fiscal transfers to states and localities (Balderston Reference Balderston1993).Footnote 8 James (Reference James1986, p. 76) also commented that regional governments were “left with odious taxes and falling revenues.” Although austerity was determined at the Reich level, the extent to which it mattered varied regionally. This variation depended on how lower levels of government allocated their revenue to different types of expenditure and what the sources of their tax revenues were. Around 40 percent of the spending cuts were implemented by local authorities, mainly municipalities and the so-called administrative divisions (Regierungsbezirke); 22 percent by the different states; and around one-third by the Reich (Newcomer Reference Newcomer1936). Hence, the impact of Reich mandated cuts on the states varied according to a number of predetermined fixed factors, including population and land area, number of schools, highway mileage, and the distribution of income (Newcomer Reference Newcomer1936, p. 205).Footnote 9

Political affinity to Brüning’s policies might have mattered, but in essence, spending cuts were mandated at the central level. The room to maneuver in the states was also highly constrained. States could no longer borrow on international capital markets after 1930, and only a small share of state spending was accounted for by local tax revenue over which a state had control. While local politicians could potentially shift spending between categories, the Reich increasingly dictated the way in which states should spend money; put caps on spending categories; and, in many instances, relied heavily on targeted Reich subsidies or transfers. Thus, states were also constrained both by an inability to legislate tax rates and by the traditional ways of redistributing tax revenue. Our bottom line is that responding to the recession with discretionary spending was not much of a possibility and both income taxFootnote 10 and expenditure were largely out of the hands of state governments and local authorities.Footnote 11

DATA

We collected data from official German sources (see our Online Data Appendix for details and Galofré-Vilà et al. (Reference Galofré-Vilà2020)). Our analysis begins by measuring the impact of austerity on electoral outcomes at the city level. Data on electoral returns for the Reichstag elections are from the official publication Statistik des Deutschen Reiches (volumes Wahlem zum Reichstag), with all the other data at the city level coming from the Statistisches Jahrbuch Deutscher Städte, which report data for cities above 50,000 inhabitants (N = 98). For each city, we collected city spending data for each fiscal year from 1929/30 to 1932/33, which includes transfers from higher levels of government and spending by budget category, in 1,000 RM. Such detailed data at the city level allow us to look at the type of spending and the potential mechanisms by which spending changes can affect electoral outcomes. The fiscal years ran from 1 April to 31 March, and when we say 1929, this refers to the fiscal year 1929/30. We also collected data from the federal transfers to cities (a variable called Überweisungen aus Reichsteuern) to construct a Bartik-style instrument, as discussed subsequently.

To test competing explanations, we further used data on city-level unemployment. Unemployment is defined as the number of people in the labor force not working and registered in the local offices as unemployed. We proxy city economic conditions by the construction of new residential apartment buildings. We also collected mortality data from the bulletins of the Reichs-Gesundheitsblatt. These bulletins report detailed mortality data at the weekly level for cities with a population larger than 100,000 inhabitants (N = 51).

We also study district- (kreis-) level data (N = 1,024), where data on taxes, but not spending, are available. Electoral and fiscal data on taxes are from the official Statistik des Deutschen Reiches. For taxes, we collected data on the number of taxpayers, total taxable income, and total revenue for each state (in 1,000 RM) on two main federally administered income taxes: the lohnsteuer, a withholding tax deducted at the source, and the einkommenssteuer, an ex-post income declaration tax only paid by middle and high rate payers. For the “wage tax” (lohnsteuer), data are available in 1928/29 and 1932/33, and for the “income tax” (einkommenssteuer) for the years 1928/29, 1929/30, and 1932/33 (Dell Reference Dell, Anthony and Thomas2007). Despite missing data for some years, the available years allow us to capture the main changes in taxation in the period of interest (September 1930–March 1933), and rather than having highly temporally disaggregated data, we rely on benchmark years under the assumption that the impact of austerity is cumulative. We also collected state-level data on taxes (the lohnsteuer and einkommenssteuer) for the same years as in the district sample.Footnote 12

From the statistical abstracts Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich, we collected state-level data on spending, unemployment (number of people in the labor force not working), an index of hourly wages,Footnote 13 and a proxy economic output (generation of electricity, in 1,000 kWh). For the latter one, we use a proxy based on electricity generation, as these two correlate closely, since the vast majority of goods and services are produced using electricity. Other district-level data used in the Online Data Appendix, such as the number of welfare recipients, are from Statistik des Deutschen Reiches (volume Die Öffentliche Fürsorge im Deutschen Reich). Table A1 reports the main summary statistics on key variables.

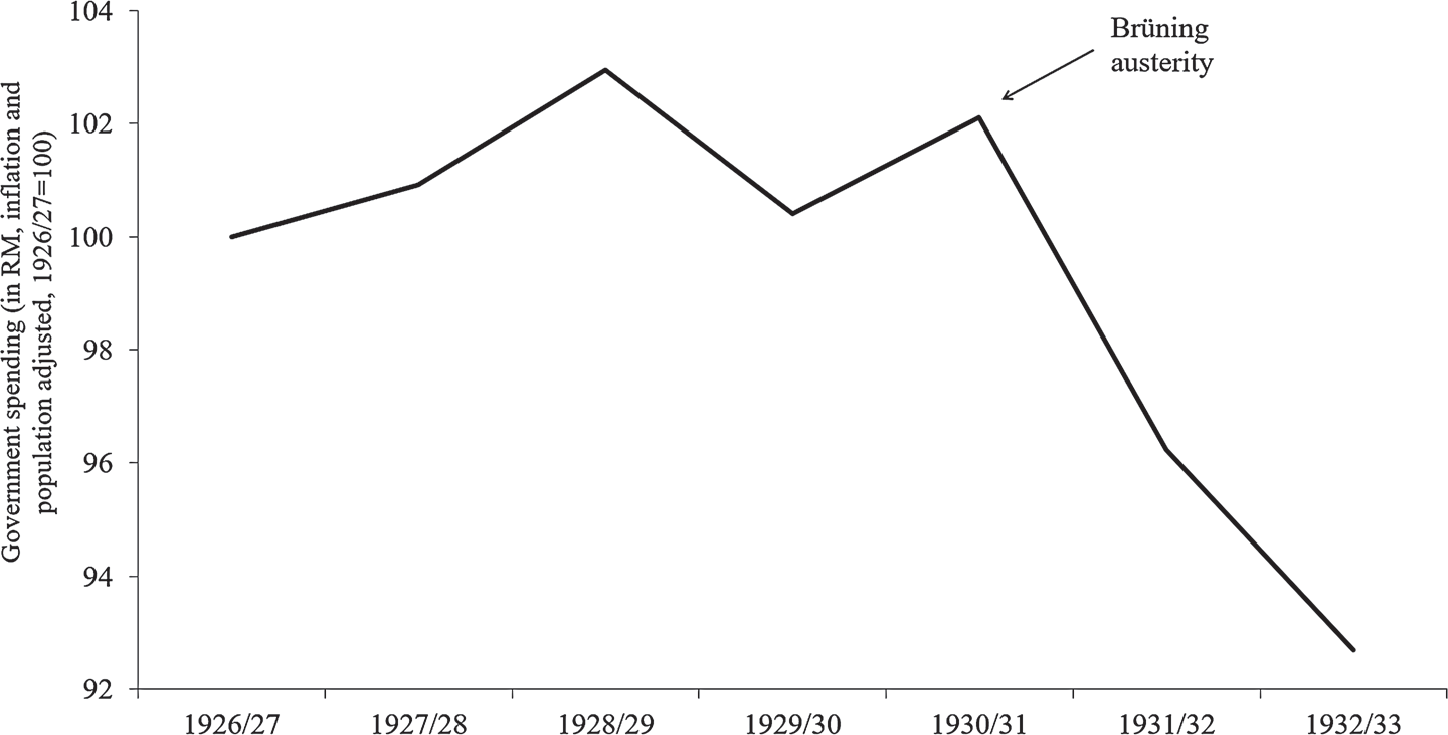

On the magnitude of austerity, as Figure 1 shows, between 1930 and 1932, state-level real expenditure was cut by 8 percent (nominal total spending fell by about 25 percent) and Reich level real expenditure fell by 14 percent (30 percent nominal).Footnote 14 These were not insignificant components of aggregate demand since, together, state and Reich expenditure totaled close to 30 percent of GDP in 1928/29.

Figure 1. DEVELOPMENT OF REAL PER CAPITA STATE SPENDING IN GERMANY, 1926/27–1932/33 (1926/27 = 100)

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of real per capita government spending between 1926/27 and 1932/33. Nominal state-level expenditure is as reported in James (Reference James1986) following fiscal years and accounting for transfers to other public authorities. Data were originally collected from Official Statistics (Statistiches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich). Nominal expenditure has been adjusted for inflation using the price index (1913/14 = 100) from Jürgen Sensch in HISTAT-Datenkompilation online (Preisindizes für die Lebenshaltung in Deutschland 1924 bis 2001) and for population using the data from Piketty and Zucman (Data Appendix for Capital is Back, Table DE1).

Source: See the text.

NAZI SUPPORT AND CITY-LEVEL SPENDING

With the launch of austerity in July 1930, the number of votes for the Nazi Party soared from 6 to 14 million between the elections of September 1930 and July 1932. Indeed, as Figure 2 suggests, there is a close negative association between the increase in the Nazi vote share between September 1930 and July 1932 and the change in city-level spending between 1929/30 and 1930/31. We next explore these issues more rigorously and implement some empirical strategies to limit biases due to endogeneity.

Figure 2. CHANGES IN VOTE FOR THE NAZI PARTY AND CITY-LEVEL SPENDING, 1930–1932

Notes: Data on the y-axis are the difference in the vote share going to the Nazi Party between the elections of September 1930 and July 1932. The x-axis shows the change in total city-level government spending in percentage points (left figure) and the change in health and well-being city-level government spending (right figure) in percentage points. The p-value in the right figure is equal to 0.040 (r = –0.249) and in the left figure is equal to 0.009 (r = –0.320).

Source: See the text.

Results

We begin our analysis reporting the results of statistical models where the dependent variable is the level of the Nazi vote share across cities in federal elections. We use city fixed effects throughout so that we rely on within-city variation to identify the impact of austerity on Nazi vote share. With these specifications, our models yield a difference-in-differences with an intensity of treatment interpretation based on

\\[\begin{gathered} NAZ{I_{ct}} = \alpha + {\beta _1}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Expenditure}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) }} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) + }}{\mu _c}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{e_{ct}}, \\

\end{gathered} \

\\[\begin{gathered} NAZ{I_{ct}} = \alpha + {\beta _1}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Expenditure}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) }} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{ct}}}}{\text{) + }}{\mu _c}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{e_{ct}}, \\

\end{gathered} \

where c is a city, t indexes elections, and NAZI denotes the vote share of the Nazi Party as measured by the ratio of the number of votes to the Nazi Party over the total number of (valid) votes cast. Expenditures ct comprises all categories of city expenditure, Unemployment ct is the number of registered unemployed in a city, Output ct is our proxy for economic output in a city, and e ct is an error term. These control variables are expressed in natural logarithms.Footnote 15 We standardize data to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one so coefficients across models are directly comparable. We also include city fixed effects (µ c) and fixed effects for the calendar years of 1932 and 1933 (δ t). We report standard errors clustered at the administrative division level. There are 44 clusters, and by clustering at the administrative division (above the city level), we allow for arbitrary spatial correlations of the error term within the cluster. Additionally, many of the variables were decided above the city level and fixed effects already pick up potential spatial correlations.

In Table 1 (Column (2)), we show that a one-standard-deviation increase in the natural logarithm of spending is associated with a decrease in Nazi vote share (in standard deviation terms) of –0.42 (95 percent confidence interval (CI): from –0.68 to –0.15). This specification, which pools data for the four elections between 1930 and 1933, is robust to the inclusion of administrative division or state by period fixed effects (Columns (3) and (4)).Footnote 16 These last specifications control for time-varying unobservable shocks or arbitrary unobserved trends at the administrative division or state level. Since shocks are likely to be highly spatially correlated, these controls mop up the effect of spending changes after controlling for local economic and political shocks.

This table also displays the results for other competing explanations for the rise of the Nazi Party. Despite the fact that the coefficient on unemployment at the city-level displays a positive sign, it is only statistically significant in Column (4). As Ferguson (1997, p. 267) notes, this is a likely outcome, as “it is a popular misconception that because high unemployment coincided with rising Nazi support, the unemployed must have voted for Hitler. Although some did, unemployed workers were more likely to turn to Communism than to Nazism.” When controlling for austerity and unemployment, in most cases, the economic output variable is also not statistically significant.

Table 1. IMPACT OF CITY EXPENDITURES ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE, ALL NATIONAL ELECTIONS 1930–1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the Nazi Party in the different elections. Equation (1) is equivalent to the results we show in Column (2). We use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the election of March 1933. We estimate the linear models with many levels of fixed effects, as in Correia (Reference Correia2017). We balance the sample for singleton groups and use a balanced panel with robust standard errors (in parentheses) clustered on 44 administrative divisions. We standardize all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Source: See the text.

Since we can differentiate party votes in the data, we next modify the outcome variable to be the vote share among other parties. This change allows us to see how austerity affected the rest of the German political spectrum. To also show that our results are not driven by a single election (or group of elections), we provide the results in three separate forest plots, pooling data for the elections of 1930 and 1933; elections of 1930 and 1932 (both elections); and the four elections between 1930 and 1933.

Results for the Nazi Party in Figure 3 show that there is a negative and statistically significant association between spending and the Nazi Party vote share in the different elections between 1930 and 1933. Results for the other parties suggest that austerity mostly drew votes from the Center Party. This is not surprising as the Center Party was Brüning’s party and the party became very unpopular for consolidating the budget. For instance, Straumann (Reference Straumann2019, p. 207) comments that “the harsh austerity measures of December 1931 … pushed the popularity of the Brüning cabinet down to a new low.” Results also display a positive sign for the SPD (although not always statistically significant) and the Communist Party (when avoiding the violent election of 1933). Results for the DNVP highlight its lack of a political position on the austerity front.

Figure 3. IMPACT OF CITY EXPENDITURES ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE, ELECTIONS 1930, 1932, AND 1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the main parties in the different elections. Models are estimated independently and adjusted for unemployment and economic output. We use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the election of March 1933. We use a balanced panel with robust standard errors clustered on 44 administrative divisions. SPD stands for the Social Democratic Party and DNVP for the German National People’s Party. In the election of 1933, the DNVP presented in the election as part of the Kampffront Schwarz-Weiß-Rot, which was an electoral alliance of three parties: the DNVP, the Stahlhelm, and Landbund. All models include city-level fixed effects, and the forest plot with the elections 1930 and 1932 (both) includes a fixed effect for 1931/32 and “all elections” fixed effects for 1932 and 1933. We standardized all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

Source: See the text.

Robustness Checks

In Table A2, we also pool all elections and study the dynamics of the effects via interaction terms. Specifically, we interacted the spending data with a dummy for each election. Therefore, we estimated three coefficients, 7/1932, 11/1932, and 1/1933, and then one for austerity uninteracted, which corresponds to the “omitted” category, which is 1930. In this way, we show that the austerity effect is stable across time, as the sample is kept stable and the reference point still remains 1930. We further test for the validity of our estimates in different ways.Footnote 17 For instance, in Table A3, we divide each of the right-hand-side variables by population to show that our fixed effects models are very likely to proxy for a stable population over the short horizon between 1930 and 1933. Table A4 further explores the interaction of the shock of the Depression with social structure. We interacted year fixed effects with the share of blue-collar workers in 1925 and the share of the population identifying as Catholic or Protestant.Footnote 18 The time interactions on religious identity are significant, suggesting a role for such interaction. However, austerity mattered in a similar way in Catholic and Protestant areas, though the impact is higher in places with a Jewish community.Footnote 19

Instrumental Variable and Endogeneity

One may worry that changes in spending were choice variables reflecting the (unobservable) state of the underlying economy or the level of local political competition. Politicians could alter spending levels in response to these and their perceptions of these and other variables, making it problematic to infer the impact of exogenous changes in spending on votes for an extreme party such as the Nazis. To deal with the potential endogeneity of expenditures, we employ a shift share instrumental variable in the spirit of Aizer (Reference Aizer2010), which relies on variation at the national level in “across-the-board” cuts imposed by Brüning. Consider the following stylized equation for total government spending G in city c in fiscal year t:

Spending in city c is composed of two components. One is federal transfers or the federally mandated level of spending ![]() . This variable could also be construed as local spending based on local claims to federal revenue streams, where the subscript F denotes federal transfers or mandates to city c. The other component,

. This variable could also be construed as local spending based on local claims to federal revenue streams, where the subscript F denotes federal transfers or mandates to city c. The other component, ![]() , is based on local decision-making and local revenues. Assuming that this spending is constant, the change in total spending between period t and period t – 1 given an (α − 1) percent change in federal spending applied to all localities (0 ≤ α ≤ 1) is given by

, is based on local decision-making and local revenues. Assuming that this spending is constant, the change in total spending between period t and period t – 1 given an (α − 1) percent change in federal spending applied to all localities (0 ≤ α ≤ 1) is given by

\[\% \Delta {G_{ct}} = \frac{{{G_{Fct}}_{ - 1}}}{{{G_{ct}}_{ - 1}}} \times (\alpha - 1).\

\[\% \Delta {G_{ct}} = \frac{{{G_{Fct}}_{ - 1}}}{{{G_{ct}}_{ - 1}}} \times (\alpha - 1).\

The absolute value of the percentage change in spending is directly related to the share of federal spending in total city spending. That is, the larger the share of G Fct−1 in G ct−1, the larger the percentage fall in total spending, (%ΔG ct), for a (α − 1)% change in G Fct−1. Our instrument, therefore, is the initial share of federal transfers in total city spending in 1929 interacted with year indicators represented by δ t, which themselves proxy for the across-the-board nationally imposed spending cuts. This two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach is reminiscent of Nakamura and Steinsson (2014) or Chodorow-Reich et al. (2012).

To satisfy exogeneity, we assume that  \[E\left[ {\left( {\frac{{{G_{Fc1929}}}}{{{G_{c1929}}}}\cdot{\delta _t}} \right){e_{ct}}} \right] = 0\. In a broader survey on shift-share instruments, Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (2020) argue that if initial shares

\[E\left[ {\left( {\frac{{{G_{Fc1929}}}}{{{G_{c1929}}}}\cdot{\delta _t}} \right){e_{ct}}} \right] = 0\. In a broader survey on shift-share instruments, Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (2020) argue that if initial shares  \[\left( {\frac{{{G_{Fc1929}}}}{{{G_{c1929}}}}} \right)\ are exogenous, the Bartik-style or shift-share instrument boils down to using initial shares (interacted with time dummies) as excluded instruments. With two sectors, they also show it is only necessary to use one sector share and this is equivalent to a Bartik approach. To satisfy the exclusion restriction, one would have to believe that reliance on the central government in 1929 was not related to the unobservables driving the change in Nazi vote share. As suggested by Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (2020), we tested this by regressing the initial share on observables such as the share of Protestants and Catholics, levels of unemployment, or the construction of new buildings. In none of the cases were these variables statistically significant. For relevance, the log deviation in spending from the within-city mean must be correlated with the initial dependency on the Reich transfers. This would evidently be true unless local spending changes completely offset (orthogonal) Reich spending changes. This is not possible since localities could not fund spending by borrowing due to financial market dislocation and due to the fact that total tax revenue was falling as a result of the decline in aggregate activity.

\[\left( {\frac{{{G_{Fc1929}}}}{{{G_{c1929}}}}} \right)\ are exogenous, the Bartik-style or shift-share instrument boils down to using initial shares (interacted with time dummies) as excluded instruments. With two sectors, they also show it is only necessary to use one sector share and this is equivalent to a Bartik approach. To satisfy the exclusion restriction, one would have to believe that reliance on the central government in 1929 was not related to the unobservables driving the change in Nazi vote share. As suggested by Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift (2020), we tested this by regressing the initial share on observables such as the share of Protestants and Catholics, levels of unemployment, or the construction of new buildings. In none of the cases were these variables statistically significant. For relevance, the log deviation in spending from the within-city mean must be correlated with the initial dependency on the Reich transfers. This would evidently be true unless local spending changes completely offset (orthogonal) Reich spending changes. This is not possible since localities could not fund spending by borrowing due to financial market dislocation and due to the fact that total tax revenue was falling as a result of the decline in aggregate activity.

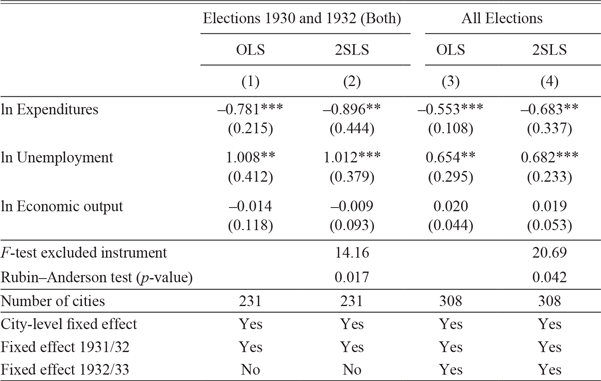

As Table 2 shows, using ordinary least squares (OLS), the impact in terms of standard deviations in vote share for the Nazi Party associated with a one-standard-deviation increase in the percentage change in spending is –0.78 (95 percent CI: from –1.21 to –0.34) in the elections of 1930 and 1932 (both) and –0.55 (95 percent CI: from –0.77 to –0.34) when considering all elections.Footnote 20 Results using 2SLS are just 15 percent larger (in absolute magnitude) than the OLS results in Column (4), showing that OLS results may not be highly biased. In Table A6, we also show the Bartik results using models in differences.

Table 2. IMPACT OF CITY EXPENDITURES ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE USING A BARTIK INSTRUMENT, NATIONAL ELECTIONS 1930, 1932, AND 1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the main parties in the different elections. We use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the election of March 1933. The first-stage coefficient on the initial average income tax rate is negative and highly significant (–0.103; p-value = 0.000; 95 percent CI: –0.129 to –0.077). We use a balanced panel with standard errors clustered on 44 administrative divisions. For details on the instrument, refer to the text. All models include time and city-level fixed effects. We standardize all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Source: See the text.

Mechanisms

In Figure 4, we modify Equation (1) and, instead of all city-level expenditure, we study the impact of changes in different types of expenditure. Interestingly, most of the effect of austerity is driven by spending changes in health and well-being (–1.03: 95 percent CI: from –1.53 to –0.52) and housing (–0.21: 95 percent CI: from –0.39 to –0.03). These were among the budgets most affected by austerity.Footnote 21 The size of the effect for spending changes in health and well-being is 32 percent higher than the overall effects of the spending changes presented in the previous table, showing that social spending changes plausibly exacerbated the suffering of the German masses. There is also a positive effect of expenditure in construction and the Nazi vote share between the elections of September 1930 and 1933. As we have already seen, by the end of 1932, von Papen and Schleicher introduced some tax discounts as well as construction and work programs, which, along with Hitler’s promise to construct an autobahn, were symbols of a new era of economic competence and the end of austerity (Voigtländer and Voth 2019). However, the effect disappears when we introduce data for the austerity years and the elections of 1932.

Figure 4. IMPACT OF CITY EXPENDITURES BY BUDGET CATEGORY ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE, ELECTIONS 1930, 1932, AND 1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the Nazi Party in the different elections. Models are estimated independently and adjusted for unemployment and economic output. We use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the elections of March 1933. We use a balanced panel with robust standard errors clustered on 44 administrative divisions. All models include city-level fixed effects, and the forest plot with the elections 1930 and 1932 (both) includes a fixed effect for 1931/32 and “all elections” fixed effects for 1931/32 and 1932/33. We standardized all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

Source: See the text.

The literature also stresses that Brüning’s fiscal plans were part of a political strategy to elicit international sympathy for German suffering, putting an end to WWI reparations.Footnote 22 Coinciding with the fiscal retrenchment, mortality rates, which had been declining, started to rise rapidly after 1932. One mechanism for the rise of populist parties is that they gain the most votes where health fares worst. This link was outlined by some commentators at the time. For instance, by the fall of October 1930, Hjalmar Schacht (former head of the Reichsbank) gave an interview to the American press saying that, “If the German people are going to starve, there are going to be many more Hitlers” (The New York Times, 3 October 1930).

Next, we report suggestive evidence that the effect of spending cuts was through the channel of higher mortality. In Table 3, we use Equation (1) and also add a control for mortality. Since we use city fixed effects, mortality here can be interpreted as excess mortality, that is, within-city changes or deviations of mortality from its within-sample mean. Instead of overall spending, we use only spending in health and well-being. Column (1) shows that after controlling for unemployment and economic output and other fixed effects, increases in spending are negatively and statistically related to Nazi Party vote. Similarly, Column (2) shows that without controlling for spending, higher mortality is associated with higher Nazi vote share. However, once we add the mortality control (Column (3)), expenditure is no longer statistically significant and the size of the coefficient declines by 34 percent. If we remove the deaths from cancers and a category for ill-defined causes, the coefficient for mortality remains statistically significant at the 1 percent level of confidence (Column (5)), but the coefficient on spending declines by more than half and is not statistically significant. Although results are weaker for infant mortality, possibly because births to the poorest families fall disproportionately during a recession (Dehejia and Lleras-Muney 2004), they display a low p-value (Column (7)). This result further illustrates that the impact of austerity was potentially channeled through suffering (as measured by changes in mortality). It is also interesting that the coefficients on unemployment and economic output, once we control for austerity, are similar before and after we include the mortality control.

Table 3. IMPACT OF CITY EXPENDITURES IN HEALTH AND WELL-BEING AND MORTALITY ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE, ALL NATIONAL ELECTIONS 1930–1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the Nazi Party in the different elections. We use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the election of March 1933. Column (1) is the baseline specification without controlling for mortality. In Columns (2) and (3), the Crude Death rate is the number of deaths within a city divided by the city-level population (×1,000). In Columns (4) and (5), from the Crude Death rate, we removed deaths from cancer and unspecified causes of death. In Columns (6) and (7) is the Infant Mortality rate measured as the number of deaths within a city below the age of one divided by the number of live births (×1,000). We use a balanced panel with robust standard errors (in parentheses) clustered on 30 administrative divisions. All models include city level fixed effects. We also add fixed effects for 1931/32 and 1932/33. We standardize all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Source: See the text.

NAZI SUPPORT AND DISTRICT-LEVEL TAXES

Results

We next move to district-level data. Since spending data at the district level are unavailable from national sources, we rely on within-district variation in income taxes as our measure of austerity. We assume that for an individual voter, changes in taxes have an impact analogous, if not proportional, to cuts in spending. Both fiscal variables would presumably have an economic and potentially psychic impact on the well-being and political preferences of an individual voter. Changes in tax rates would alter an agent’s budget constraint and choices much the same as a direct change in income due to modifications of targeted transfers or other government spending on services. Alternatively, utility derived from public good flows could also be altered to the extent that public goods are a function of spending or the revenue that is necessary to finance such spending.

We model the impact of austerity on Nazi vote share using the following equation:

\[\begin{gathered}

{\text{NAZ}}{{\text{I}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ = }}{\beta _1}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Tax Rate (a)}}{{\text{)}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Wage}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{)}} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{) + }}{\beta _{\text{4}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{) + }}{\mu _d}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{{\text{e}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{,}} \\

\end{gathered} \

\[\begin{gathered}

{\text{NAZ}}{{\text{I}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ = }}{\beta _1}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Tax Rate (a)}}{{\text{)}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Wage}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{)}} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{) + }}{\beta _{\text{4}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ (Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{) + }}{\mu _d}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{{\text{e}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{,}} \\

\end{gathered} \

where the average Tax Rate (either the average rate of income or wage taxes and denoted by a) is calculated as the ratio of tax revenue divided by total declared taxable income. Tax rates are indexed by districts d, other controls by states s, and t is an election period (September 1930, July 1932, November 1932, or March 1933). Since we do not have annual data on taxes, we linked the income taxes for the fiscal year 1929/30 to the elections of September 1930 and the taxes for the fiscal year 1932/33 to the elections of 1932 and 1933. Since wage taxes are unavailable for the fiscal year 1929/30, we had to link the wage taxes for 1928/29 to the elections of 1930 and the taxes for 1932/33 to the elections of 1932 and 1933. NAZI denotes the percentage point vote share of the Nazi Party in the different federal elections. We also include district fixed effects (µ d) and a fixed effect for the fiscal year 1932/33 (δ t) and report standard errors clustered at the district and state levels.

The results in Table 4 (Column (1)) show that the impact in terms of standard deviations in vote share for the Nazi Party associated with a one-standard-deviation rise in the natural logarithm of the average tax rate is 0.16 using income taxes (95 percent CI: from 0.78 to 0.25) and 0.19 using wage taxes (95 percent CI: from 0.09 to 0.30). This result suggests that the Nazi Party received more votes in districts with greater austerity when austerity is measured as rises in the tax rate.

To control for endogeneity, we also instrumented the tax rate with the level of the average income tax rate in 1928 (Column (7)) interacted with time dummies. The percentage change in the average income tax rate T is the weighted average of statutory rates with the weights equal to the share of total taxable income within each tax bracket. Assuming constant shares, the observed percentage change in the average tax rate, denoted by ![]() for district d in period t, is given by

for district d in period t, is given by

where the weights, ω db are the ratio of total taxable income in bracket b to total taxable income across all brackets in an initial year and τ bt values are the nationally defined statutory tax rates for each bracket.

In 1930, under austerity, statutory income tax rates for each bracket were raised equally nationwide. The change in the average depends on the initial shares. As Pinkham-Goldsmith, Sorkin, and Swift (2020) show, the relevant Bartik-style instrument for this national shock to tax rates with b shares and one time period is equivalent to using the initial shares as instruments. The average income tax rate in 1928 is, again, the sum of these shares (at the district level), with each share being multiplied by the same constant, τ b1928 (the 1928 statutory tax rate), across all districts. We use this initial value (interacted with period fixed effects) as the excluded instrument. The first stage coefficient on the excluded instrument, the initial average income tax rate, is negative and statistically significant. The negative sign is due to the fact that the statutory tax rates rose more in proportional terms for the lowest tax brackets than the higher tax brackets.

Using the initial average income tax rate as an excluded instrument, we find a positive relationship between changes in tax rates and Nazi vote share (Column (7)). Results are not dependent on clustering at the district level or at the state level. Nevertheless, the sizes of the standardized coefficients using the instrumental variables (IV) are between two and three times larger than those using OLS, and since wage taxes were unavailable for 1929/30, we cannot use this instrument for wage taxes. There is no obvious reason why the point estimate on taxes using the IV approach is so much larger than in OLS. However, there is a possibility of some heterogeneity in the impact of tax increases such that the nationally imposed tax changes had a much larger impact in certain kinds of districts.

In Table A7, we also use a differenced model. We further show that results are robust to the addition of state fixed effects, which allows for differential state-level trends and potentially mops up some of the within-state correlations in the error term.Footnote 23 In Column (4), we weight the regressions by the level of population to emphasize the data from the larger districts and states and eliminate undue influence from smaller states. In Columns (5) and (6), we also add the lagged Nazi vote share to control for differential growth based on initial Nazi support in 1930. Lagged values refer to the election immediately prior to the latest election in the differenced dependent variable. Again, results are also very stable across specifications.

In Table A8, we explore potential heterogeneity in the impact of austerity. Here, we split the sample for values above and below the median vote share for the Nazi Party in the election of 1928 and the median values for the share of the labor force that is in agriculture, in industry, in civil service, self-employed, and in blue-collar occupations using the census data of 1925. When we stratify the sample, we show that the impact of austerity had a larger effect in pre-1930 Nazi strongholds; in districts with a low share of blue-collar workers; in rural, agricultural, and less industrialized areas; and in localities with a higher share of civil servants and self-employed workers. It seems that austerity was a bigger determinant for those living in small towns or the countryside and those who were self-employed, rather than residents of the largest cities who were more likely to become unemployed, who turned to the Communist Party.

Table 4. IMPACT OF DISTRICT INCOME AND WAGE TAXES ON THE NAZI PARTY VOTE SHARE USING A BARTIK INSTRUMENT, NATIONAL ELECTIONS 1930, 1932, AND 1933

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share (×100) of the valid votes cast going to the Nazi Party in the different elections. The average tax rate is calculated as tax revenue divided by total declared taxable income. For wages, unemployment, and economic output, we use the controls of 1929 for the election of September 1930, 1931 for the elections of July and November 1932, and 1932 for the election of March 1933. For income taxes, we use the values for 1928/29, 1929/30, and 1932/33 and for wage taxes 1928/29 and 1932/33. For more details on the tax data, refer to the text. We use a balanced panel with standard errors clustered as stated in the table. All models include a district fixed effects and a fixed effect for the fiscal year 1932/33. For the details in Column (7) and the instrumental variable used, refer to the text. The F-test of the excluded instrument in Column (7) is equal to 17.93, and the p-value for the Rubin–Anderson test is 0.001. The first-stage results are statistically significant at 1 percent. We standardize all variables with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Source: See the text.

Robustness Checks

We pursued a number of additional robustness checks. In Figure A2, we drop one state at a time to show that our results are not driven by a particular state. In Table A9, we also study the impact of taxes on the vote shares for the main political parties. Additionally, in Table A10, we use first differences to calculate the taxes as the percentage point change (the change in the level) instead of the percentage change in average income and wage tax rates.

For another robustness check, we use a policy discontinuity design at state borders—a method which uses a potentially more relevant set of control groups.Footnote 24 For each election our border district-pair data are organized to have at least two observations in each pair p (one for each state in the pair). A given district appears in the data k times (for each election t) if it borders k districts. In total, there are 459 districts that lie along a state border, and for each border district, we match all the neighboring districts that are located on opposite sides of the borders, yielding a total of 1,080 border pairs.Footnote 25 The district-pair match on the opposite side of a state border is a plausible control group, since while there are substantial differences in treatment intensity of austerity, due to differing state-level policies and initial conditions, these pairs are very similar politically and economically and, approaching the border, most controls vary smoothly but the treatment variable jumps (Table A11). Hence, variation in austerity at the district level across state borders would be due to differences in state-level decisions on austerity.

Our difference-in-differences specification is as follows:

\[\begin{gathered}

{\text{NAZ}}{{\text{I}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ = }}\alpha {\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{1}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Surplus (a}}{{\text{)}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Wage}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{st}}}} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{4}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\mu _{p/pt}}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{{\text{e}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{,}} \\

\end{gathered} \

\[\begin{gathered}

{\text{NAZ}}{{\text{I}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{ = }}\alpha {\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{1}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Surplus (a}}{{\text{)}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{2}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Wage}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{st}}}} \\

{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{3}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Unemploymen}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\beta _{\text{4}}}{\text{ }}\ln {\text{ Outpu}}{{\text{t}}_{{\text{st}}}}{\text{ + }}{\mu _{p/pt}}{\text{ + }}{\delta _t}{\text{ + }}{{\text{e}}_{{\text{dt}}}}{\text{,}} \\

\end{gathered} \

where NAZI denotes the Nazi Party vote share in district d in year t. To unite spending and taxes in the same equation, we measure austerity as the fiscal Surplus: the logarithm of the total state income taxes paid minus the logarithm of state-level expenditure. We use income and wage taxes in alternative specifications indexed by a. Using a higher level of aggregation than the district for spending and taxes makes variation in treatment more plausible since state changes are determined by within-state factors. Additionally, spending data are only available at the state level. Along with the standard controls as in previous equations, we use district (µ d), time fixed effects (δ t), or district pair by year effects and cluster the standard errors at the state and district pair level. This level of clustering also accounts for potential mechanical spatial correlations given the presence of districts in multiple pairs. In Table 5, we provide four types of specifications according to whether we use district-pair fixed effects (µ p) or district-pair fixed effects by year interactions (µ pt).

We find that the variable Surplus for the border-pair sample is also positive and statistically significant. For instance, a time-varying district-pair fixed effects model using Surplus 1 gives a standardized coefficient of 0.28 (95 percent CI: from 0.15 to 0.42) and using Surplus 2 a coefficient of 0.23 (95 percent CI: from 0.06 to 0.40). This well-identified piece of variation, comparing neighboring districts that straddle state borders, produces consistent results with the full sample. In Table A12, we also obtain consistent results by instrumenting the percentage change in the average tax rate with the initial level of taxes paid in 1928 using district-pair and state-level clustering along with district-pair fixed effects.

Table 5. IMPACT OF STATE-LEVEL AUSTERITY ON THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY IN THE RESTRICTED SAMPLE OF CROSS-DISTRICT PAIRS LOCATED ON OPPOSITE SIDES OF THE BORDERS

Notes: Dependent variable is the percentage share of the valid votes cast going to the Nazi Party in the elections of September 1930, July 1932, November 1932, and March 1933. Fiscal surplus is defined as the log of the total state revenue in income or wage taxes minus the log of municipal plus state spending. For the years used in the controls, refer to the text. We have 459 districts that lie along a state border (the number of states is equal to 27 and the number of districts is reduced to 401 in the models after accounting for missing data), and for each border district, we match all the neighboring districts that are located on opposite sides of the borders, yielding a total of 1,080 “directed” border pairs. Each district that lies along a state border, on average, has 2.36 pair-districts across the border (with an associated standard deviation of 1.48). The minimum number of pairs for a district is 1 and the maximum is 10. Fiscal Surplus 1 combines government spending and wage taxes and Fiscal Surplus 2 government spending and income taxes. We use a balanced panel and the methodology from Dube, Lester, and Reich (2010) for two-way clustering with standard errors (in parentheses) clustered at the state and district-pair level. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Source: See the text.

CONCLUSION

This paper offers econometric support for the idea that the austerity measures implemented between 1930 and 1932 immiserized and radicalized the German electorate. Each one-standard-deviation increase in austerity measured in several different ways was associated with between one-quarter to one-half of one standard deviation of the dependent variable. Yet, austerity is only one factor affecting the rise of the Nazi Party and there are other factors at work such as the role of German business (Ferguson and Voth 2008), the historical roots of antisemitism (Voigtländer and Voth 2012), the influence of social capital (Satyanath, Voigtländer, and Voth 2017), the banking collapse (Doerr et al. 2018), and the power of radio propaganda (Adena et al. 2015).

Austerity worsened the situation of low-income households and the Nazi Party became very efficient at channeling the austerity-driven German suffering and mass discontent. We exploit this mechanism by showing that austerity was associated with higher mortality. This reinforces the idea that, had Brüning relaxed the efforts to consolidate the budget, things might have been different.

The corollary seems clear: Even when the particular history of a country precludes a populist extreme-right option, austerity policies are likely to produce an intense rejection of the established political parties, with the subsequent dramatic alteration of the political order. The case of Weimar, explored in this paper, provides a timely example that imposing too much austerity and too many punitive conditions cannot only be self-defeating, but can also unleash a series of unintended political consequences, with truly unpredictable and potentially tragic results.