Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic cancer in the USA [Reference Doll and Winn1]. Among women over 50 with intact uteri, the incidence of EC among non-Hispanic Black women has surpassed that among non-Hispanic White women [Reference Doll and Winn1,Reference Jamison, Noone, Ries, Lee and Edwards2] and their mortality rate is nearly double that of non-Hispanic White women [Reference DeSantis, Miller, Goding Sauer, Jemal and Siegel3]. The prevalence of obesity and diabetes, among the strongest risk factors for EC, is higher for Black women [Reference Hales, Carroll, Fryar and Ogden4,5]. Delays in care seeking, disparities in access, and potential differences in tumor biology are also implicated as causes of racial disparities in mortality [Reference Collins, Holcomb, Chapman-Davis, Khabele and Farley6,Reference Doll, Khor and Odem-Davis7].

Symptom recognition is central to early diagnosis. Natural menopause occurs on average at age 51 years in the USA, but frequent occurrence of episodic bleeding after menopause likely contributes to uncertainties about the definition of post-menopausal bleeding (PMB) associated with EC risk [Reference Astrup and Olivarius Nde8], especially given that 90% of women with PMB do not have EC, with potentially higher frequencies among Black women [Reference Ghoubara, Sundar and Ewies9]. Patients and caregivers may dismiss PMB as a normal variant and delay care seeking [Reference Clarke, Long, Del Mar Morillo, Arbyn, Bakkum-Gamez and Wentzensen10,Reference Doll, Hempstead, Alson, Sage and Lavallee11]. Cost, discomfort, and medical expertise required for diagnostic evaluation may also pose barriers to work-up of PMB [Reference DeStephano, Bakkum-Gamez, Kaunitz, Ridgeway and Sherman12]. Transvaginal sonography, endometrial biopsy, and hysteroscopy produce discomfort and risk of complications, especially among women with severe obesity. Less invasive self-sampling has shown promise for improving cervical cancer screening [Reference Sanner, Wikström, Strand, Lindell and Wilander13,Reference Winer, Lin and Tiro14]. However, acceptability of self-sampling in the context of triaging women with PMB for diagnostic work-up is unknown. Acceptability of tampon collection is also unknown; HPV sampling for cervical cancer is done using other types of self-sampling devices for fluid collection. The success of in-clinic “proof-of-principle” studies using vaginal tampon collection, combined with sensitive and specific molecular testing for EC, suggests that home-based self-collection may have utility in diagnostic work-up of PMB [Reference Bakkum-Gamez, Wentzensen and Maurer15] and it may increase access and early detection [Reference Doll, Hempstead, Alson, Sage and Lavallee11]. However, most new testing approaches for early cancer detection fail when deployed in real-world settings, in part because researchers did not engage potential users to understand feasibility and acceptability [Reference Walter, Thompson and Wellwood16]. We conducted community-based focus groups to explore perceptions of White and Black women, as well as gather formative feedback on a sampling kit designed for use in a pilot study.

Methods and Materials

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited near Jacksonville, Florida, via flyers in the local academic medical center and through distribution by a local community research advisory group. Eligibility was age 40 years or older and self-report Black or White race. Participants were offered $50 remuneration. This study was reviewed by a community research advisory board and approved by the affiliated Institutional Review Board (IRB# 19-001140).

Data Collection

Members of the study team with experience in qualitative research and community engagement designed and conducted the focus groups. Black and White women were included in separate focus groups in community locations. Women provided oral consent and completed a brief survey about tampon use and attitudes prior to the discussion (Appendix A). Results on questions related to participant characteristics and attitudes are presented here, to provide context for the focus group findings. The semi-structured moderator guide had three parts: awareness of EC and EC risk factors; experience and impressions of tampon use; and feedback on the proposed tampon collection kit. Participants were provided testing kits and instruction sheets for the third part of the discussion. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Moderators answered questions but did not present formal education on EC, as the intent of the groups was to understand the experiences and impressions of women without educational intervention.

Data Analysis

We tabulated the frequency and percentage of participants by categorical and ordered survey responses. The sample median and interquartile range were used to describe continuous survey responses. Comparisons between Black and White participants were made using Fisher’s exact test (categorical responses) and Wilcoxon rank sum test (continuous and ordered responses). We used methods of qualitative content analysis, completed by study team members with relevant and complementary social science and medical research backgrounds. Transcripts were reviewed independently, and then researchers met to discuss impressions and develop a coding framework of a priori topics from the interview guide (e.g., knowledge of EC) and inductively derived topics. Transcripts were independently coded by two researchers, and coding differences were discussed and reconciled. Transcripts were entered into qualitative software (NVivo 12.6; QSR International) to facilitate queries for analysis, including exploration of differences between groups.

Results

Six focus groups were held in February and March 2020, three with Black women (N = 31) and three with White women (N = 26). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Compared to White participants, Black participants were younger and reported a lower frequency of ever having used a tampon. More White participants reported being post-menopausal. No participants in either group reported Hispanic ethnicity.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

a Information was not available for 1 participant.

b Wilcoxon rank sum test.

c Fisher exact test.

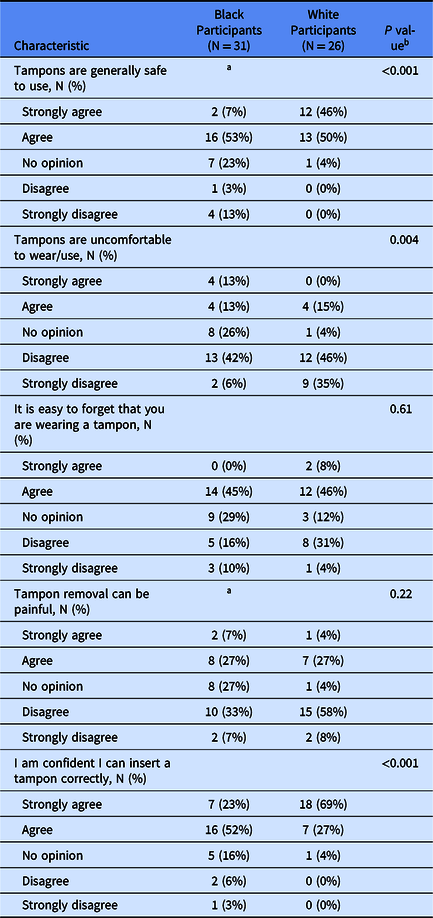

Participant survey responses on tampon use are summarized in Table 2. Nearly a quarter of all Black participants reported that they had no opinion on tampon attitude questions. Among White participants, 96% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “Tampons are generally safe to use,” whereas only 60% of Black participants gave these responses. Black participants were also more likely to say that tampons were uncomfortable (26% vs 15% agreed or strongly agreed), and significantly fewer said that they were confident that they could insert a tampon correctly, although a majority in both groups agreed that they could do so.

Table 2. Views on tampon use

a Information was not available for 1 participant.

b Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Qualitative Findings

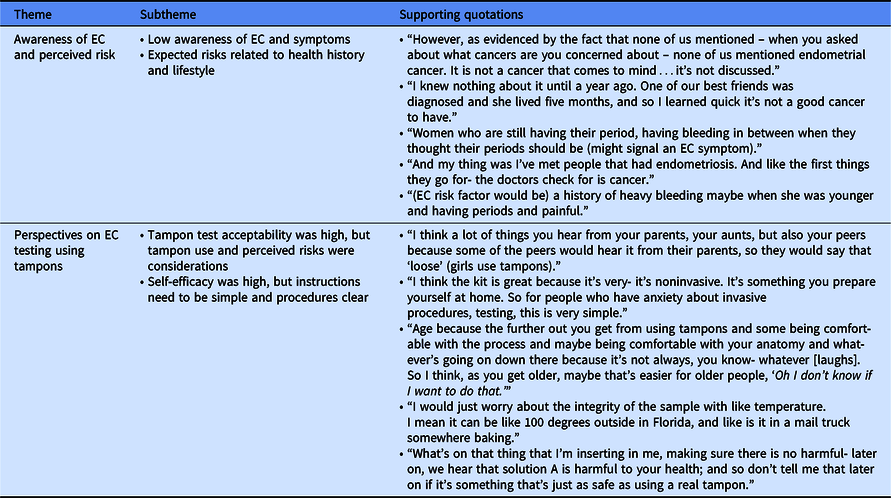

Qualitative findings are organized in two themes, which are displayed in Table 3 with supporting quotations. Themes represent data from all six focus groups. Potential differences between participants in the Black and White focus groups are highlighted below when the study team agreed that differences were notable.

Table 3. Qualitative findings by theme

EC, endometrial cancer.

Awareness of EC and Perceived Risk

Low awareness of EC and symptoms

Awareness of EC was low in all focus groups, with most women saying they had never heard of EC, although two women reported knowing someone with EC. Participants expected that symptoms would include bloating, heavy bleeding or discharge, and pain with intercourse. In terms of menstruation, women spoke about abnormal cycles most frequently, especially more frequent bleeding than expected for a pre-menopausal woman.

Expected risks related to health history and lifestyle

Reported knowledge of EC risk factors was also low. Suspected risk factors included personal or family history of cancer, heavy bleeding at young age, and history of pregnancy or hormone therapy. Participants in all groups discussed endometriosis when asked about EC familiarly. Several Black participants stated that either they or a contact had the condition, and the similarity of the terms led participants to assume they were somehow related. Women also mentioned behavioral risk factors including smoking and drug use, obesity, having multiple sexual partners, having a “stressed” lifestyle, and not attending regular health care visits. Race and ethnicity were mentioned in two groups as potentially being related to EC, including risk related to delays in seeking care among Black women.

Perspectives on EC Testing Using Tampons

Tampon test acceptability was high but tampon use and perceived risks were considerations

The idea of using a tampon for testing had high acceptability (e.g., minimally invasive and convenient), but personal tampon experience was a primary consideration. Older age was reported as potentially associated with lower acceptability because older or post-menopausal women might experience dryness-related discomfort. Noted risks of tampon use included those related to forgetting about tampon placement. In terms of a tampon-based testing procedure, perceived risks included any chemicals that might be used on the tampon. Some women also noted concern related to DNA-based research, which may carry risks related to confidentiality. Discussion of risk perception was especially prevalent among Black participants, who reported that they talked with other women, including family members, about tampons. These conversations were occasionally a source of myths, including association of tampons and sexual activity.

Self-efficacy was high but instructions need to be simple and procedures clear

Especially among women with experience using tampons, reported self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in ability to complete home testing) was high. Participant review of the pilot kit highlighted opportunities to make the instructions clearer, simpler, and easier to follow, but some women thought the instructions were overwhelming enough that they expressed a preference for in-clinic tampon collection instead, especially in response to instructions dictating a clean environment, a time range of tampon placement (30 min to 2 h), and the need to store the sample at a specified temperature. Participants expressed concern that mistakes would impact the usefulness of the sample or the accuracy of the results.

Discussion

Risk perception is an important motivator of behaviors [Reference Maddux and Rogers17]. Knowledge of EC risk factors was minimal in this study, including the link with obesity, which is the strongest and most prevalent risk [Reference Hales, Carroll, Fryar and Ogden4]. Although women linked abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to EC, concerns focused primarily on frequent or heavier bleeding among pre-menopausal women. High prevalence of irregular bleed secondary to leiomyomata among Black women in particular may lead some patients to “normalize PMB,” which, along with stigma discussing bleeding and inadequate efforts to elicit histories of PMB, may delay care seeking [Reference Doll, Khor and Odem-Davis7,Reference Clarke, Long, Del Mar Morillo, Arbyn, Bakkum-Gamez and Wentzensen10]. Furthermore, despite low awareness of EC, this study found relatively high familiarity with endometriosis. Presumed connection between these conditions could serve as a barrier to early detection if women associate lack of an endometriosis diagnosis as indicating lower EC risk. These data strongly suggest the need for education to increase awareness of PMB specifically and EC risk factors more broadly.

Currently, work-up for EC diagnosis involves clinical procedures that may be costly, inconvenient, and, in some cases, risky. The science of home-based testing, combined with sensitive and specific molecular testing for EC, makes home-based testing to triage potential cases with pre-menopausal AUB and PMB a compelling strategy to increase access to care if women find it acceptable. Participants in this study said home-testing might be convenient, but acceptability was associated with personal tampon experience and perceived risk. Tampon use has been found to be lower among Black women than among White women, but the research is limited and has been focused primarily on younger women [Reference Finkelstein and von Eye18,Reference Romo and Berenson19]. Further research is needed on perceptions of tampons and tampon use among a broader population, including women closer to post-menopausal ages, especially considering our finding that women were concerned about vaginal dryness common with older age. Future research could also explore whether women view one-time, short-duration tampon use for sample collection differently than regular, repeated use.

Participants also raised concerns about the complexity of testing instructions and procedures. Improved formatting and visuals may alleviate these concerns, as might videos that demonstrate testing procedures or smartphone apps that monitor tampon insertion time. However, it is notable that the participants—most with high educational attainment—reported that in-clinic tampon testing might be preferable if instructions or procedures were too complex. Instructions may also need to detail benefits and demands of all options and safeguards in place for home sampling accuracy. Our pilot study is currently deploying a test kit, refined based on the findings reported here, to further assess feasibility, including sample stability. Further, this study team has pilot-tested markers for benign endometrial DNA, which can provide information about the quality of samples that tested negative for EC-specific markers.

The strengths of this study include community health advisory board review of study procedures and data collection instruments. Analysis by the multidisciplinary study team enriched interpretation and bolsters credibility of the findings. This study also has limitations. The number of focus groups and participants was suitable for qualitative research on personal experiences. Survey responses provide context for the focus group findings and generate hypotheses for further exploration, but the small number of participants is not suitable for statistical generalizability. Likewise, the use of focus groups with both Black and White women was intended to ensure representation of Black voices and to explore potential differences in attitudes, experiences, and information needs, but findings should not be generalized broadly. These differences should be studied further with larger-scale quantitative methods appropriate for hypothesis testing. Women in this study also had high levels of education and were insured, and none of the participants reported Hispanic ethnicity. Future research is needed to understand the views of women with different levels of education or lack of insurance coverage, as well as to further explore issues of race, ethnicity, and culture. We did not administer a post-focus group survey, so it is not known whether attitudes changed because of the group discussions. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that EC disparities are multi-level and include racial disparities related to factors like clinician bias [Reference Doll20]. Future research should include exploration of health-system barriers that compound EC disparities. This study team is currently establishing a local women’s health advisory board to advance this work.

Conclusion

Education about EC and risk factors, especially PMB, is needed to motivate action related to early detection. Using the tampon as a self-collection testing device may be acceptable, but further effort is needed to address the concerns of Black women.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.787

Acknowledgements

The study team would like to thank the focus group participants and the members of the community advisory board for their contributions to this study.

This research was funded by a grant from Mayo Clinic Office of Women’s Health (M.E.S).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.