Introduction

The cultural and economic positions of radical right parties (RRPs) have been widely scrutinized in the last few decades (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2016; Rathgeb and Busemeyer, Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022).

Comparative research investigating party placement in the new multidimensional space of political conflict has located these parties within the authoritarian pole of the socio-cultural dimension (Kitschelt and McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). The RRPs' emergence and success have mainly been explained as a silent counter-revolution to the social change that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s and led to the spread of a new political culture dominated by post-material values (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi1992; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2018). For a long time, their economic program has been seen as secondary in their agenda and used to put their core ideological positions into practice (i.e. nativism, authoritarianism, and populism) and expand their electorate (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019).

However, more recent studies have questioned the irrelevance of the economic dimension in the RRPs' political agenda (Rathgeb, Reference Rathgeb2021). Contrary to the idea that their economic positions are blurred (Rovny, Reference Rovny2013), comparative works have demonstrated that distributive preferences and, in particular, support for the welfare state – combined with a chauvinist approach – have gained increasing salience within RRP programs (e.g. Afonso, Reference Afonso2015; Enggist and Pinggera, Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022).

Against this background, family policy is an intriguing issue to scrutinize as the family can be considered a cross-dimensional issue with both material and post-material implications.

On the one hand, family positions are structured around considerations concerning gender equality and the institution of marriage. In this sense, the family is a cultural issue, where libertarian actors oppose authoritarian ones. RRPs have been depicted as strongly authoritarian, supporting traditional gender roles, and having a heteronormative view of the family (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015).

On the other hand, as the literature on varieties of familialism and that on social investment (SI) points out, family policy implies the material (re)distribution of resources in terms of both cash transfers and services (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992; Leitner, Reference Leitner2003; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2012; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018). The actors' positions can be detected by considering their preferences regarding the degree of familialism – that is, supporting the family in its caring function – and de-familialism – that is, facilitating care taking place outside of the family.

The material-oriented preferences on the family issue are linked to cultural ones. The decision regarding which policy instruments to expand is embedded in a more general consideration regarding the family policy's cultural goal, since the specific mix between in-kind and not-in-kind measures produces different outcomes relating to gender equality.

To date, very little has been known about the RRPs' specific family policy positions. We may presume that they favor familialism to reinforce the traditional division of gender roles. At the same time, they are expected not to support the expansion of de-familializing measures. Recent empirical works have confirmed these suppositions (Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2016; Meardi and Guardiancich, Reference Meardi and Guardiancich2022). However, it is still unclear whether all RRPs share a similar family policy agenda or whether cross-country differences may be detected.

Furthermore, there is no in-depth understanding of the factors that account for their positions.

Relying on the theoretical insights from the literature on the varieties of familialism and SI, the article scrutinizes the RRP family policy agenda in six European countries: Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. The following research questions will be addressed:

First, what are the RRPs' family policy positions in terms of support for familialism and de-familialism? Is their family policy agenda distinct from that of the other ‘familles spirituelles’?

Second, which factors may explain the RRP family policy agenda and cross-country similarities or differences?

Concerning the second question, the work considers two inter-linked variables. On the one hand, it looks at the radical right's constituency and its preferences regarding family. On the other, the study probes the family policy institutions of the countries analyzed. We assume that policy legacies inform RRP preferences by triggering a counter-policy feedback mechanism.

The contributions of this work are theoretical, empirical, and methodological.

First, the article adds new theoretical insights to the literature concerning RRPs' welfare agenda. Relying on partisan politics literature and historical institutionalism, the article provides a multi-causal theoretical framework that combines a classical political-oriented variable – that is, constituency preferences – with an institutional one – that is, counter-policy feedback.

Second, the work compares six countries representing different varieties of familialism (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003). The empirical analysis produces comparative findings concerning the family policy positions of the RRPs with respect to their national party systems.

Finally, from a methodological perspective, the study is based on a content analysis of party manifestos. The coding scheme enriches the method developed by the Comparative Party Manifesto Project with the theoretical tools supplied by the varieties of familialism and SI literature. The scheme can be easily replicated in other case studies.

The article is structured as follows. First, some considerations regarding analyzing the parties' family policy agenda are provided. Second, the explanatory framework to understand the RRPs' positions is discussed. Third, the case selection and the method are presented. Then the findings of the empirical analysis are shown and discussed. The last part of the article is devoted to the conclusions.

Analyzing the family policy agenda of political parties: theoretical considerations

In the party politics literature, family policy positions remain under-theorized. A dichotomic approach in terms of pro/con no longer seems adequate to grasp actual policy preferences in the post-Fordist age (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2022).

Since the end of the 1960s, the family has undergone a real, though still incomplete, revolution (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2009). Typical gender roles within the family have been questioned. Women have entered the labor market and claimed an equal re-distribution of caring tasks within households, while men have increasingly asked for more involvement in child-rearing. In several countries, the typical male-breadwinner family model – with men at their jobs and women at home taking care of children – has gradually been replaced by a dual-earner family model, with both the parents working full-time and caring tasks more equally distributed (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992; Mätzke and Ostner, Reference Mätzke and Ostner2010). Such a change is far from being completed (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2009).

In such a changing scenario, it is clear that political conflict around family policy is no longer structured around a general expansion or retrenchment of resources. What is at stake is how the family should be supported and, therefore, which specific policy instruments will be expanded or retrenched (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018).

In this regard, the literature on the varieties of familialism and SI is a useful theoretical tool for re-conceptualizing a political party's family policy agenda (e.g. Lewis, Reference Lewis1992; Leitner, Reference Leitner2003; Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2010; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018).

As previously stated, detecting different kinds of policy instruments within a family policy is possible. On the one hand, we find familializing policy instruments whose primary goal is strengthening the family's caring function through passive measures (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003). Within this category, we find family allowances, child benefits, cash-for-care, and tax rebates for families.

On the other hand, de-familializing policy instruments facilitate care outside the family (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003; Saraceno and Keck, Reference Saraceno and Keck2010). Childcare represents the main instrument to achieve this goal.

Parental leaves are more complex policy instruments to classify, as several scholars see them as familializing measures since they allow parents, especially mothers, to opt-out of a job due to caring tasks (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003). Otherwise, SI scholars have pointed out that leaves may have a de-gendering effect and, therefore, indirectly de-familializing (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2012; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018). This is true when considering a short leave, which positively influences a mother's chances of re-entering the labor market. Simultaneously, periods reserved for fathers are present and associated with high replacement rates that positively affect a woman's employment outcomes (Kotsadam and Finseraas, Reference Kotsadam and Finseraas2011). However, an extended leave impinges on a woman's working career (Boeckmann et al., Reference Boeckmann, Misra and Budig2015). In a nutshell, only short parental leaves and paternity leave/daddy quotas produce a de-familializing effect.

A party's positions can be conceived in relation to their degree of support for familialism Footnote 1 and de-familialism. A party can back familialism while overlooking de-familialism or the opposite. When the support shown for familializing and de-familializing measures is quite balanced, an optional familialism position has been taken (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003). There is also the possibility that parties say nothing about family policies or are against de-familialism and familialism. In this case, we can refer to implicit de-familialism (Leitner, Reference Leitner2003).

Familializing and de-familializing policy instruments have different political goals. When supporting familialism, parties back the traditional male-breadwinner family model. In contrast, when fostering de-familialism, the dual-earner family model is being upheld.

When considering the radical right, the family is seen as an integral part of their conservative rhetoric; therefore, their positions are not blurred. Furthermore, these parties have developed a well-defined pro-welfare agenda (Enggist and Pinggera, Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022). However, they tend to favor the traditional Fordist policy programs – for example, such compensatory measures as pensions. Because of their conservative background and preferences for passive measures, they will likely display stronger support for familialism and less support for de-familialism than the left parties. These latter have been depicted as libertarian actors, favoring gender equality inside and outside the household (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010; Naumann, Reference Naumann, Bonoli and Natali2012). The RRP's agenda is also expected to differ from that promoted by the center-right parties. Liberals have championed gender equality, though preferring more market-oriented solutions, such as private childcare (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010). Since the beginning of the post-Fordist age, Conservatives have gradually distanced themselves from the male-breadwinner model, coupling support for familializing and de-familializing measures to get working women's support and also to please those employers with a predominately female labor force (Naumann, Reference Naumann, Bonoli and Natali2012; Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016; Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2022).

Therefore, our preliminary expectations are the following:

1a. RRPs support familializing policy instruments to a higher level than the other party families.

1b. RRPs back de-familializing measures to a lower level than the other party families.

Understanding the RRP family policy agenda: constituency preferences and counter-policy feedback

To explain RRP's family policy positions, we consider two interlinked variables: the cultural preferences of their constituencies and the counter-policy feedback mechanism created by national-level family policy institutions.

Constituency preferences

Partisan politics assumes that a party's welfare preferences are driven by its constituency (e.g. Korpi, Reference Korpi1989). Parties are thus motivated to pursue those policies supported by their distinctive core constituencies. When considering family policy, a traditionalist vision of gender relations is often associated with familialism (Korpi, Reference Korpi2000; Pavolini and Scalise, Reference Pavolini, Scalise, Burroni, Pavolini and Regini2021). On the contrary, a more libertarian approach is linked chiefly with de-familialism. Therefore, parties will set their policy positions depending on the electors' cultural preferences. Compared to the median voter, an RRP's electorate is expected to have a more traditionalist position concerning the family. The radical right's family agenda can thus be explained as a way to please its authoritarian constituency. Additionally, RRPs are increasingly supported by blue-collar workers and, to a lesser extent, the petty-bourgeois. As documented by the literature (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015), these two social groups tend to be very conservative regarding post-materialist values. In other words, not only is the whole RRPs' electorate more authoritarian-oriented than the average voter, but their core electoral groups are more inclined to favor traditional gender roles. Consequently, RRP voters are more likely to reward the expansion of familializing measures that help families in their caring functions and reinforce gender roles. In contrast, de-familializing measures will be less attractive since they question the male-breadwinner family model. Besides, RRPs are supposed to attract a predominately male constituency, which will have little interest in issues that primarily affect working women.

Our second expectation is the following one:

2. There is a correlation between an elector's cultural attitudes toward family and a party's family policy positions. In the case of the radical right, their constituency is supposed to be more authoritarian than the median voter, thus pushing them to support familialism while disregarding de-familializing measures.

Counter-policy feedback

While highlighting the importance of the voter–party linkage, recent studies on partisan politics have underlined that the policy positions of political parties are increasingly conditioned by welfare institutions (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Gerring and Picot2012; Häusermann and Palier, Reference Häusermann, Palier and Hemerijck2017). Following the insights provided by historical institutionalism (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993, Reference Pierson2001), these studies stress that, once welfare institutions are established, they create a broad group of institutional winners and a weaker group of institutional losers. The former are those who benefit from the current configuration of welfare institutions, while the latter are those who have, or perceive to have, a very low or no gain at all from these institutions in terms of material resources (e.g. cash transfers or services) or immaterial ones (e.g. the maintenance of a specific social order). Institutional winners tend to be strongly mobilized and react intensely to the potential cutting of their acquired rights by punishing politicians for unpopular initiatives (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001). From an electoral perspective, this means that, for political parties, taking a position that radically questions the status quo can be risky. If they wish to avoid electoral punishment, they must not only align their policy positions with their core voters' preferences, but also propose reforms that do not dramatically alter the institutional winners' interests. In other words, a party's policy positions are informed by a policy feedback mechanism (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993, Reference Pierson2001).

This mechanism primarily affects mainstream parties from the left and the right for two interconnected reasons. First, these are government parties that have had a lasting and direct relationship with the welfare institutions. Over time, they have implemented policy reforms, thus creating policy legacies that they hardly wish to reverse. Or they have inherited welfare legacies from past governments, which are difficult to change out of fear of electoral punishment and due to the stickiness of the institutions (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993, Reference Pierson2001).Footnote 2 The specific configuration of the institutional winners and losers crystallized in a country is the sub-product of the policies promoted over time by the mainstream right and left.

Second, though experiencing a decline, mainstream parties in Western Europe still attract the relative majority of the institutional winners' votes.Footnote 3 They compete in elections to win and head single-party governments or be key partners in coalition governments. It is risky to antagonize those who benefit from the current status quo, given that they represent a broad sector of the electorate. In this picture, pleasing a minority and ill-mobilized institutional losers – by dramatically modifying welfare arrangements – is not electorally strategic for the mainstream parties since this would trigger a counter-reaction from the winners. Only when losers outnumber winners and are proved to be highly coordinated do their votes become pivotal. The institutional losers' interests are barely represented by the mainstream parties until that moment.

Policy feedback is expected to affect RRPs differently. First, these new challengers are relatively young as they have emerged only in the last few decades. Consequently, their relationship with welfare institutions is weak, given that they have little or no experience in government.Footnote 4 The fact that they have been chiefly opposition parties means that, over time, they did not contribute to shaping the national welfare state, nor have they had to deal concretely with the stickiness of institutions inherited by past governments. Accordingly, they do not directly respond to the institutional winners, like the mainstream parties. On the contrary, they try to attract the disappointed electors (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) to broaden their consensus. In other words, the institutional losers emerging from the welfare institutions are the RRPs' potential voter reservoir. If an institutional loser's policy preferences coincide with the RRPs' electorate, the radical right will be motivated to strengthen its policy positions further. However, if these preferences do not align, the RRPs could try to find an in-between position that satisfies its core electorate as well as pleases the institutional losers.

In a nutshell, welfare institutions positively influence mainstream parties, pushing them to support well-established welfare programs to keep the winners' consensus. In the case of the radical right, this mechanism generates a negative mechanism: RRPs are motivated to hold alternative policies to gain the losers' votes. In other words, the RRPs' policy positions are informed by a counter-policy feedback.

Different configurations of welfare institutions produce different groups of winners and losers. Policy feedback mechanisms vary across countries and provide political parties with diverse electoral incentives and disincentives to support or oppose policy programs.

In those countries – especially the Scandinavian ones – where the dual-earner family model has been predominant since the 1960s, the institutional winners – first of all, working mothers – are expected to oppose the retrenchment of childcare and be little interested in familializing measures. In these countries, a ‘childcare consensus’ emerged (e.g. Duvander and Ellingsæter, Reference Duvander and Ellingsæter2016), which pressured Social-Democratic and center-right parties to endorse de-familialism if they wanted to secure the votes of the institutional winners. Simultaneously, those living in male-breadwinner families fall within the group of institutional losers. Their familistic preferences find less or no support in mainstream parties. The RRPs can fill this political vacuum, setting up a male-breadwinner policy agenda based on a high level of support for familializing measures and a very low – or even absent – support for de-familializing ones.

A similar picture may emerge in those countries historically characterized by a high degree of familialism but where a shift toward de-familialism has begun. Welfare policies are not immobile objects (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001; Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2010), and policy changes can occur. This has happened in Continental and some Southern European countries, where the economic, social, and demographic changes have questioned the male-breadwinner family model. Since the end of the 1990s, both the center-left and center-right have started to recalibrate the welfare states, which has also included the promotion of the dual-earner family model (Palier, Reference Palier2010). While the provision of services remains lower than in Scandinavian, such a policy change has created a new group of institutional winners – for example, working mothers – which benefits from the expansion of childcare and are now politically relevant. Conversely, a new group of losers – for example, housewives living in a single-earner family – have emerged.

In these countries, the RRPs have a further electoral incentive to adopt a male-breadwinner policy agenda to win the vote of this new loser group. Nevertheless, compared to the Scandinavian countries, familialism has remained relatively high in continental Europe. Governments, especially of the center-right, have mixed the expansion of de-familializing and familializing measures, thus opting for optional familialism. RRPs do not have a monopoly on the loser group's votes since the latter can remain loyal to center-right parties – and especially to the more conservative fringes of these parties – or even to center-left ones – in case they do not cut passive measures. With the losers' vote not secured and the need to widen their electoral base, the radical right could decide to propose a slightly less radical agenda to gain the support of some less traditionalist voters. Therefore, a more moderate counter-policy feedback effect is expected.

By contrast, mainstream parties have few incentives to promote a shift toward the dual-earner family model in those countries characterized by a frozen landscape (Palier, Reference Palier2010), where de-familializing measures are historically poorly developed, and a change in policy is far from occurring. In this case, authoritarian electors are included within the institutional winner group, and their preferences are already well represented by the mainstream parties, especially the center-right. No political vacuum must be filled. Though they still have to respond to the authoritarian preferences of their electorate, RRPs will have fewer electoral incentives to further radicalize their male-breadwinner policy agenda. Otherwise, they could still include some de-familializing measures at a low level to gain the institutional losers' support.

To conclude, the fourth and last expectation follows:

4. Counter-policy feedback informs RRP family policy positions. In those countries where de-familialism is deep-rooted or a substantial change in this direction has been initiated, RRPs are further motivated to pursue a male-breadwinner policy agenda. Where familialism is well anchored in a country and de-familializing measures are poorly developed, RRPs are less motivated to radicalize their male-breadwinner agenda.

Case selection and methodFootnote 5

We choose a medium-N comparative research design to detect the RRP family policy positions and test the explanatory framework. The case studies were selected based on three criteria: first, the country has an RRP that competed in the most recent national elections. Second, the RRP is electorally relevant, surpassing a 5% threshold in the election. Lastly, the country's family policy belongs to one of Leitner's varieties of familialism (Table 1).

Table 1. Leitner's ideal types of familialism (selected case studies in brackets)

Source: Leitner (Reference Leitner2003: 358) and author's elaboration.

By the combination of these three criteria, the cases analyzed are: (a) Sweden (Swedish Democrats, SD) and Finland (True Finns, PS), representing the de-familialism countries. Spain (Vox) has also been included in this group as, in the last few years, this country has initiated a process to move away from implicit familialism toward de-familialism; (b) Austria (Freedom Party of Austria, FPÖ) and Germany (Alliance for Germany, AfD) representing the countries that shifted from explicit familialism toward optional familialism; and (c) Italy (the League and Brothers of Italy, FdI) whose family policy continues to be characterized by explicit familialism.Footnote 6

Following the approach developed by Budge et al. (Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Tannenbaum, Fording, Hearl, Kim, McDonald and Mendes2001), we have assumed that parties express their positions in their political programs. We thus have conducted a content analysis of the party manifestos issued during the national latest elections. The content analysis strategy resembles that of Enggist and Pinggera (Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022). To identify the extent to which RRPs support familialism and de-familialism, we recoded the data as quasi-sentences from the Comparative Manifesto Project Database (CMP). The quasi-sentences were assigned to three categories: domain A, ‘Familializing Policy Instruments’; domain B, ‘De-Familializing Policy Instruments’; and domain C, ‘Ambiguous Policy Instruments’. We also coded whether the sentiment was positive (expanding) or negative (retrenching).

The quantitative results of the content analysis were used to construct a De-Familialism/Familialism Party Index. For the De-familialism Party Index, the number of negative quasi-sentences on de-familialism was subtracted from the number of positive quasi-stances on de-familialism and taken as a share of all quasi-stances on family policy:

Similarly, for the Familialism Party Index, the number of negative quasi-sentences on familialism was subtracted from the number of positive quasi-stances on familialism and taken as a share of all quasi-stances on family policy:

Both indexes range from −100 (strong opposition) to +100 (strong support), with 0 meaning that there is no support.

We calculated the values for the RRPs and the main political parties in each country selected (for a total of 36 political parties). Except for the True Finns, the indexes of all the political parties analyzed do not take negative values, indicating that a party's familialism and de-familialism positions are predominately structured in support intensity (from no support at all to very high) and not in terms of support vs. opposition.

In order to understand whether family policy is a key issue for the radical right, we also provided an indicator of its relative salience in the electoral manifestos. Salience is calculated as the number of all the quasi-sentences devoted to the family policy, regardless of the specific domains, as a share of all the quasi-sentences present in each manifestoFootnote 7:

To detect positions regarding the family of a party's constituency, data from the 2017 wave of the European Value Survey (EVS) and Round 8 of the European Social Survey (ESS) were used. ESS data were also used to scrutinize the RRPs' constituency composition and the institutional losers and winners' electoral preferences.

To empirically measure current family policy institutions in the countries analyzed, we created three additive indexes for ‘familialism’, ‘de-familialism,’ and one capturing their combined effect. The indexes were built on quantitative indicators from the OECD Family Dataset. Figure 1 shows the Familialism National Index on one axis with the De-familialism National Index on the other. The indexes generally confirm Leitner's ideal-types.Footnote 8 The de-familializing countries of Sweden and Finland are located in the upper-left quadrant. Spain is also included in this quadrant, though showing a lower degree of familialism and de-familialism compared to Scandinavian countries. In the upper-left quadrant are Germany and Austria, which combine moderate-high de-familialism with high familialism, resulting in optional familialism. Finally, Italy is located in the bottom-left quadrant, displaying a relatively high level of familialism and a very low degree of de-familialism (explicit familialism).

Figure 1. De-familialism and Familialism National Indexes, the late 2010s.

Source: Author's analysis of OECD data.

Note: The de-familialism and familialism indexes range from a minimum value of 1 to a maximum value of 16.

Empirical analysis

The RRPs' family policy agenda

Figure 2 shows the overall salience given by the main party families or familles spirituelles to family policy in their electoral manifestos.

Figure 2. Salience devoted to family policy by party family, the late 2010s.

Source: Author's analysis from Comparative Manifesto Project.

Note: Values indicate the percentage of the statements devoted to family policy in party manifestos. On average, party families dedicate 2.1% of their manifestos to family policy.

The empirical analysis unveils that RRPs do debate the concept of family in distributive terms to a greater extent than the other parties, including the Conservatives. Their family agenda thus goes beyond ethical issues, such as opposition to same-sex marriage or abortion. This finding contradicts the position-blurring theory. However, it is only a partial contradiction, considering the cross-dimensional nature of the family issue. Materialist positions on family policy are indeed informed by post-materialist values. Unsurprisingly, the radical right emphasizes this specific welfare state policy, which links the economic and cultural dimensions of party competition.

Figure 3 shows the positions of the familles spirituelles on familialism and de-familialism. Following Enggist and Pinggera (Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022), the figures display the aggregated differences in country meansFootnote 9 for each party family rather than absolute values. This analysis strategy avoids bias due to the different representations of party families among the countries selected.

Figure 3. De-familialism Party Index and Familialism Party Indexes, the late 2010s.

Note: A value of 0 indicates that the party family's support for familialism and/or de-familialism is equal to the country's mean. Positive values indicate higher than average support for familialism and/or de-familialism, while negative values mean that a party family supports familialism and/or de-familialism to a lower degree than the national average.

The radical right shows a high Familialism Index (+35.9) and a low De-Familialism Index (−32.3). In other words, the radical right supports de-familializing policy instruments, especially childcare, to a much lower degree than the country means, while backing familializing policy instruments (cash transfers) to a significantly higher degree.

RRPs differ considerably from leftist parties (e.g. Social Democrats, Greens, the radical left) – and Liberals, which occupy the upper-left quadrant. As expected, on average, these parties support de-familialism more and familialism less than their country means.

Furthermore, the radical right's agenda differs from the Conservatives'. Data show that the latter continues to promote familialism, but their position on de-familialism is by and large aligned with the country means. The value is even higher for some parties, such as the ÖVP in Austria and, in a significant way, the National Coalition Party in Finland. Conversely, the radical right remains the stronghold of the male-breadwinner model, refusing to endorse the new dual-earner family consensus. Their support of childcare or paternity leaves remains very limited.

The empirical analysis thus confirms our first expectation: the radical right has a familistic agenda, which is clearly distinct from that of the other party families.

Explaining RRPs' family policy agenda: constituency’ preferences

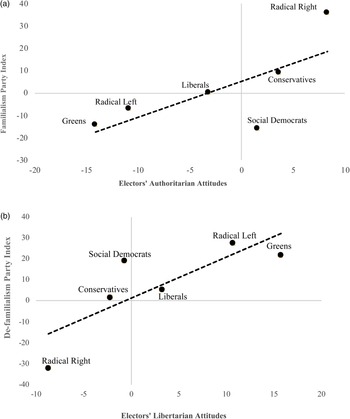

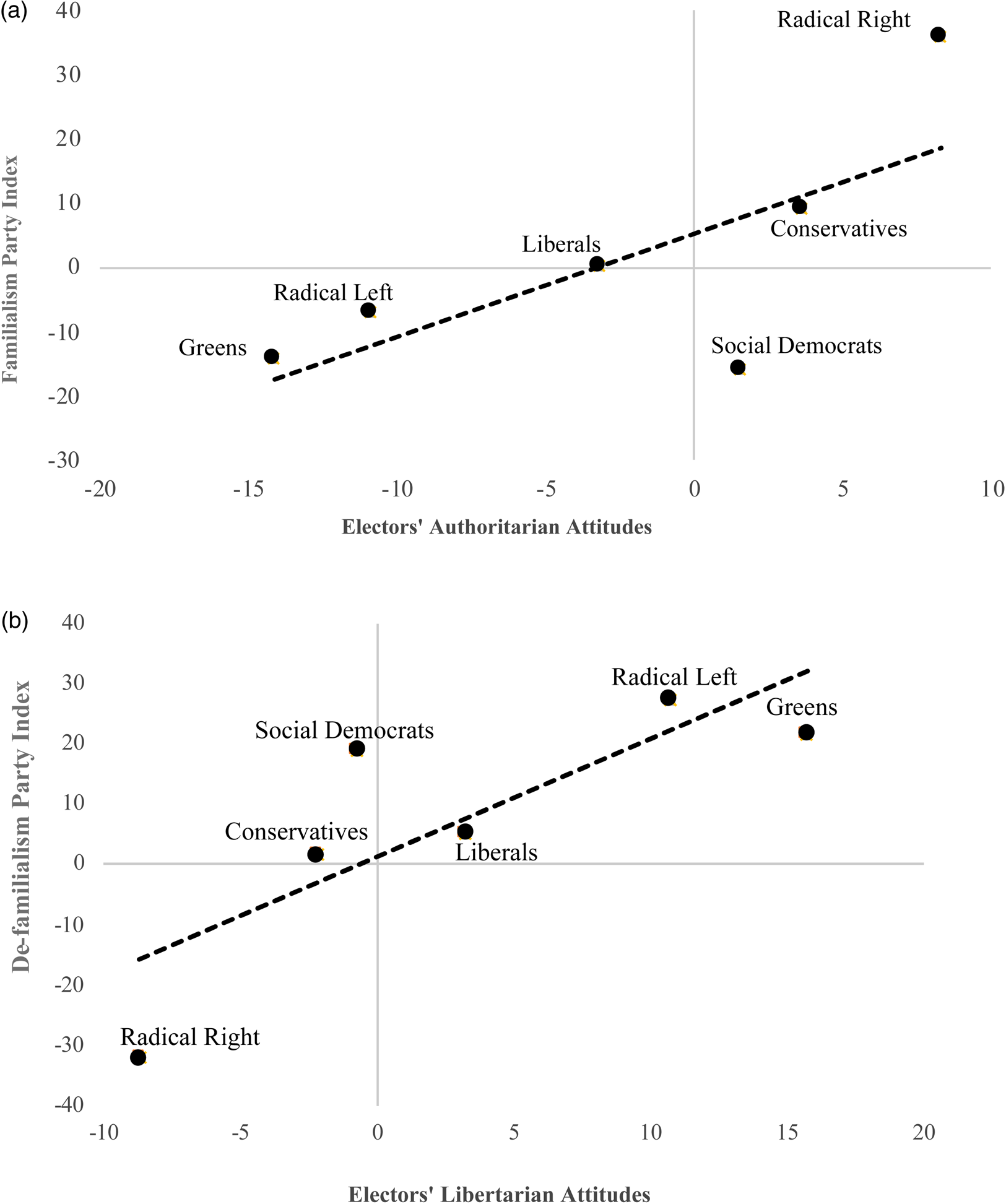

Figures 4a and 4b show the constituency preferences regarding the family issue by familles spirituelles.

Figure 4. Electors' cultural preferences and Familialism/De-Familialism Party Indexes, the late 2010s. (a) Electors' authoritarian attitudes and Familialism Party Index. (b) Electors' libertarian attitudes and De-Familialism Party Index.

Note: Concerning the Familialism/De-familialism Party Index, a value of 0 indicates that the party family's support of familialism/de-familialism is equal to the country's mean. Positive values indicate higher than average support for familialism/de-familialism, while negative values mean that a party family supports familialism and/or de-familialism to a lower degree than the national average. Concerning Electors' Authoritarian/Libertarian attitudes, positive values indicate a more authoritarian/libertarian inclination than the country's mean.

We show aggregated deviations to country means. Positive values indicate that the electorate displays a more authoritarian (Figure 4a) or libertarian (Figure 4b) preference regarding family compared to the mean, while negative values indicate a less authoritarian/libertarian attitude.

The Familialism (Figure 4a) and De-familialism Party Indexes (Figure 4b) have also been included in the two figures to assess their correlation with the electors' conservative and libertarian attitudes.

The figures confirm this correlation and suggest that the more authoritarian a party constituency's attitude is, the higher the Familialism Party Index is. At the same time, the more libertarian a party constituency is, the higher the De-Familialism Party Index scores. The electorates of the ‘New Left’ – the Greens and the radical left – and, to a lesser extent, the Liberals are shown to be more libertarian and less authoritarian than the median elector, and this explains these parties' medium-to-high support for de-familialism and their lower promotion (or on-average promotion in the case of the Liberals) of familialism. The Conservative electorate appears more conservative and slightly less libertarian, thus pushing these parties to back familialism to a greater extent while maintaining average support for de-familializing measures.

It is interesting to note that, compared to the electorate mean, Social Democratic electors display a slightly more authoritarian position. Nevertheless, Social Democrats have realigned their positions toward de-familialism, thus creating a disconnection with a part of their constituency.

When moving to the radical right's electorate, its preferences are straightforward: a significantly higher inclination than the median voter toward a traditionalist view of the family and, consequently, a lower libertarian approach. This explains why the RRPs are more motivated to strongly support familialism while disregarding de-familializing measures. Furthermore, the family agenda of the radical right may attract those authoritarian blue-collar workers disappointed by the dual-earner model consensus endorsed by the mainstream center-left parties.

If we consider the electorate's specific composition, Table G in the Supplementary material shows that, on average, blue-collar workers represent the core social group supporting the RRPs. Besides, except for the radical right of the continental countries – AfD and FPÖ – even the petty bourgeoisie can be considered a pivotal constituency. As the literature suggests and Table F in the Supplementary material confirms, these two post-industrial social classes tend to have a more authoritarian stance regarding family.

The strength of this ‘authoritarian alliance’ varies across the six parties. It constitutes the majority of the electors in the cases of SD (59.6%) and the League (50.5%), while it has a relative majority when considering True Finns (43.7%), Vox (38.5%), and AfD (42.6%). However, it is weaker in the cases of FPÖ (32.2%) and FdI (36.7%). Yet, for all the RRPs considered, even service workers represent a key electorate – they are the largest group of the constituencies of FPÖ and Vox and the second largest in the cases of SD, True Finns, and FdI. As Table F shows, this group displays slightly more authoritarian attitudes toward the family than the workforce's mean. Therefore, if we include service workers within the ‘authoritarian electoral alliance’, this latter represents the majority of the voters in all six parties' constituencies (on average, 66% of the whole electorate). The alliance is particularly strong in the Scandinavian radical right (83.8% for SD and 68.9% for True Finns) and weaker (but still firmly majoritarian) when considering AfD (54.8%) and FdI (58%).

Furthermore, for all the RRPs analyzed, women are underrepresented compared to men, and, except for the Lega and FdI, such a gender gap is high or very high (Table H in the Supplementary material). Therefore, the data confirm the hypothesis that the RRP's familistic agenda is a tool for pleasing their predominately male authoritarian constituencies, especially their core social groups.

Explaining the RRPs' family policy agenda: counter-policy feedback

The aggregated data we have discussed show that RRPs have a distinct family policy agenda compared to the other by familles spirituelles. The following steps are to assess to what extent the RRPs' family policy positions are informed by a counter-feedback mechanism.

Figure 5a displays the De-familialism and Familialism Party Indexes in the six countries selected.

Figure 5. Parties' family positions in the six selected countries, the late 2010s: (a) de-familialism countries, (b) optional familialism countries, and (c) explicit familialism countries.

Focusing on the radical right parties, cross-country differences are evident when considering the de-familialism index. Figure 6 shows the family policy national indexes on one axis and the de-familialism party indexes on the other. The figure suggests a counter-policy feedback mechanism mediating the formation of the RRP's preferences.

Figure 6. Counter policy feed-back mechanism.

Note: The Family Policy National Index ranges from −16 to +16. Positive values mean that the country's family policy is more biased toward de-familialism, while negative values indicate that the country's family policy is more biased toward familialism.

In the two de-familialist countries, Sweden and Finland – which display the highest family policy national indexes – True Finns and SD record very low support for de-familialism. The expansion of childcare is barely debated in their manifestos. Compared to the other RRPs, these two parties display the highest deviance from their country means.

Since the 1960s, Sweden has promoted a family policy model firmly centered on universal public childcare and gender equality (Björnberg and Dahlgren, Reference Björnberg, Dahlgren, Ostner and Schmitt2008). Even in recent times, government support for the dual-earner family model remains high (Tunberger and Sigle-Rushton, Reference Tunberger and Sigle-Rushton2011).

Scholars consider Finland part of the Nordic dual-earner model (Korpi, Reference Korpi2000; Forssén et al., Reference Forssén, Jaakola, Ritakallio, Ostner and Schmitt2008). However, this country has always been characterized by a stronger emphasis on freedom of choice concerning childcare. Compared to Sweden, Finland's level of de-familialism is lower due to a minor expansion of childcare and longstanding use of cash-for-care. Nevertheless, by a comparative standard, the country remains closed to the dual-earner family model (Forssén et al., Reference Forssén, Jaakola, Ritakallio, Ostner and Schmitt2008), especially considering the historically high female employment rate and the generous father leaves.

The dual-earner policy legacy of these two countries thus provides the RRPs with a further electoral incentive to promote a male-breadwinner policy agenda, which is not only instrumental to gaining the consensus of their strong authoritarian electors but also in securing the institutional losers' votes – the male-breadwinner families – which felt they had been left behind. The mainstream right and left in both countries have primarily endorsed the dual-earner family model (see Figure 5). Consequently, the capacity of these parties to gain over time, the male breadwinner families' consensus has substantially diminished (Table 2). This is especially true when considering Finland. In the late 2010s, only 28.5% of these institutional losers voted for the SDP and the National Coalition Party (−17 percentage points, pp), compared to the early Aughts. This ‘abandoned’ group was increasingly attracted over time by the True Finns' agenda (+18.3 pp). In Sweden the SAP and the Moderate Party managed to limit the loss (−2.3 pp) and the SD’ consensus remained stable. However, if we adopt a wider definition of ‘male-breadwinner family’ – thus including all the families in which only one adult within the household is currently in a paid jobFootnote 10 – the size of the ‘abandoned’ group is larger (−12.3 pp) and the losers showed to reward the SD (+10.8 pp).

Table 2. Male-breadwinner familiesa' support for the mainstream partiesb, and the RRPsc (%), t1 − t2, and changed

Source: European Social Survey (ESS), Rounds 1, 7, 8, and 9.

a Male-breadwinner families, narrow definition: one (male) adult is in paid job and the partner is a housewife; wider definition: one (male) adult is in paid job and the partner is not in paid job. For Sweden and Austria values according to the wider definition are also displayed (in square brackets).

b The percentages refer to the sum of the male-breadwinner families' vote shares of the two main center-right and center-left parties in the six countries under analysis. The Mainstream Right and Left parties considered are the following ones: ÖVP and SPÖ for Austria; CDU-CSU and SPD for Germany; the National Coalition Party and SDP for Finland; SAP and the Moderate Party for Sweden; PP and PSOE for Spain; and FI and PD (Left Democrats plus The Daisy in the early 2000s) for Italy.

c For Italy, we summed the votes for The League with the FdI's.

d t2 refers to the late 2010s. In this case, we used ESS Round 9 (2018). Concerning t1, we relied on ESS Round 1 to detect male-breadwinner families' support for the mainstream parties. Conversely, we were obliged to use different ESS rounds when analysing to the RRPs according to the availability of the data. More precisely, we relied on Round 1 (2001) for Austria and Finland, Round 7 (2014) for Germany and Sweden Round 8 (2016) for Italy, while no data is available for Spain.

Interestingly, the two mainstream parties in Finland – the National Coalition and the Social Democrats – display no support for familializing policy instruments in the last elections. As previously said, cash-for-care has long been a specific measure within Finnish family policy (Ellingsæter, Reference Ellingsæter2012), thus creating an extensive group of institutional winners along with those using formal childcare. However, institutional change is slowly taking place, with expenditure for cash benefits dropping from 1.6% of the GDP in 2001 to 1.2% in 2017, while the childcare take-up rate for children aged 0–2 has been gradually scaling up (from 24.6 in 2005 to 33.4 in 2018) (OECD, 2021). Accordingly, the home-care allowance financing decreased by 30% during the last decade (KELA, 2021). This institutional change thus created a new institutional loser group that seems to be pleased by the male-breadwinner agenda of the True Finns. Furthermore, its extreme position (−74) is not surprising since this party also has to compete with another authoritarian political force, the Finnish Centre, which strongly opposes de-familializing measures.

A similar picture also emerges when considering Spain, where Vox adopted a clear male-breadwinner policy agenda. Interestingly, its Party De-familialism Index score resembles the Scandinavian radical right's. This Mediterranean country has initiated an impressive re-orientation toward the dual-earner family model since the mid-1990s under Aznar's right-wing government and Zapatero's left-wing governments in the Aughts (León, Reference León, Guillén and León2011). From that moment on, childcare has been massively expanded, and the take-up rate for children aged 0–2 is now higher than the Austrian and Finnish ones.

Accordingly, as shown in Figure 5, a new dual-earner consensus has emerged, with all the political parties supporting de-familialism, including the People's Party, which, nonetheless, displays lower support than the national average. Moreover, it drastically cut childcare expenditure to cope with the financial and economic crisis during its period in office in the 2010s (Jessoula and Natili, Reference Jessoula and Natili2019). Contrary to Finland – and more similar to Sweden – the PP and the PSOE's capacity to attract the male-breadwinner's family votes remains high (49%, Table 2). Nevertheless, such capacity has been drastically reduced compared to the early Aughts (−36.4 pp).

The radical institutional change in Spain has moved the country away from a strong familistic legacy toward a still not complete model of de-familialism. This shift allowed Vox to further radicalize its family policy agenda to gain the consensus of institutional losers (9% of them voted for the new party in the late 2010s), which found lower representation in the mainstream parties, including the PP.

Furthermore, Spain's familistic policy legacy has to be intended as an ‘implicit’ rather than an ‘explicit’ familialism (León and Pavolini, Reference León and Pavolini2014). Spanish expenditure on cash benefits has always been modest, so it has remained even in the last decade. In the elections analyzed, the political debate prioritized the expansion of childcare, while familializing measures were debated to a lesser degree. Institutional losers are (or seem to be) doubly penalized. Although cash transfers to help families in their caring tasks remain limited, the resources have mainly been allocated to de-familializing measures. In this context, losers can be pleased by Vox's family agenda, which not only almost neglects childcare but proposes to reverse the historical underfunding of family cash benefits

Even in Austria and Germany, the FPÖ and AfD have adopted a male-breadwinner policy agenda. However, compared to the True Finns, SD, and Vox, these two parties display a slightly lower deviance from the country means. In these cases, the counter-feedback mechanisms appear slightly weaker than in the Scandinavian countries and Spain.

Since the late 1990s, both countries have initiated a gradual effort to move away from the Bismarckian tradition that characterizes the Austrian and German family policies firmly centered on the male-breadwinner model and to endorse de-familializing measures (Blum, Reference Blum2014). This change is more evident in Germany, where childcare has been dramatically expanded since the Red-Green coalition government at the end of the 1990s and has continued to be supported under Merkel's 20-year government (Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016). Instead, the pace of change was more moderate in Austria, and reforms were generally less far-reaching (Blum, Reference Blum2010; Leitner, Reference Leitner2010). Nevertheless, even in Austria childcare entered Austria's political agenda, and in 2007, the coalition government made up by the main center-right and center-left parties, SPÖ and ÖVP, agreed on creating between 6000 and 8000 new childcare places (Blum, Reference Blum2014). Therefore, a new childcare consensus emerged in the two countries, supported by the Social-Democrats (the SPÖ and the SPD) and the Conservatives (the ÖVP and the CDU-CSU) (Figure 6).

Like in Scandinavia, the FPÖ and the AfD have counter-reacted against this changing background to gain and secure the votes of the early winners of the male-breadwinner family model. However, the fact that their support for de-familialism deviates from their country means to a lesser extent than True Finns, SD, and Vox can be explained by considering that familialism remains strong in Austria and Germany. The expansion of childcare in Germany has been associated with the introduction of cash-for-care programs, firmly supported by the Bavarian partner of the CDU, that is, the CSU (Naumann, Reference Naumann, Bonoli and Natali2012). At the end of the 2010s, the cash benefits expenditure decreased (−15 pp compared to the early Aughts), but the drop was less radical than in Finland. The cut in Austria has been more evident (−24 pp, from 2.5 to 1.9%). Nonetheless, expenditure for cash benefits remains among the highest in advanced western economies. In other words, despite the threats of policy changes that have taken place since the end of the 1990s, the early institutional winners of the male breadwinner model have not been turned into an ultimate loser group.

Furthermore, German male-breadwinner families substantially decreased their support for the CDU-CSU and the SPD (−21.8 pp), but to a lesser extent than the Spanish ones, and almost 50% still continue to vote for these mainstream parties (Table 2). If we consider the center-right, the CDU-CSU took a much more moderate position, compared, for example, to the mainstream right in Finland (NCP), which allowed the party to limit the electoral loss.Footnote 11 The electoral vacuum that AfD may fill is, therefore, more limited. Over time, the party increased its consensus among male-breadwinner families (+6 pp).

The Austrian ÖVP adopted more precise dual-earner positions. However, when in power, it expanded familializing measures (e.g. the Family Bonus Plus reform), while retrenchment targeted only non-Austrians (Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2020). In other words, even the ‘losers’ in Austria can find some sort of political representation from the mainstream parties. Accordingly, in the late 2010s, though the ÖVP and the SPÖ showed to have a high decline in institutional-loser support, male-breadwinner families still voted for them (47%Footnote 12). In this scenario, the FPÖ substantially scaled up its consensus (+9.5 pp), but the competition for the institutional losers' vote from the mainstream right and left remains higher than in Finland and Spain.

Therefore, a male-breadwinner policy agenda containing some minor de-familializing measures may help FPÖ and AfD gain votes from other social groups – for example, working mothers – thus broadening their consensus. Furthermore, concerning the German case, within the AfD's constituency, the ‘authoritarian alliance’, though still majoritarian, is comparatively weaker than the Scandinavian RRPs. This could have incentivized AfD to promote some de-familializing programs like childcare (though to a limited extent) to get the consensus of some more liberal-oriented groups, such as managers, representing a critical electoral group for the party.

Finally, the counter-policy effect is different in Italy. The Lega and FdI display the highest support for de-familialism among the RRPs analyzed. The Lega's position is even higher than the national average, while FdI's is only slightly lower. While it is true that their family agenda is biased toward the male-breadwinner model – as demonstrated by their more significant support for de-familializing measures – it is less radical compared to other RRPs. This can be explained by considering that, contrary to Spain, Italy remains an almost frozen landscape regarding family policy (Naldini and Saraceno, Reference Naldini and Saraceno2008). The familistic policy legacy has persisted over time, with no radical changes (Da Roit and Sabatinelli, Reference Da Roit and Sabatinelli2013). The expenditure for family services has remained very modest and almost unchanged over the last two decades. The childcare take-up rate for children aged 0–2 is still one of the lowest among Western European countries, with substantial regional differences.

If some changes can be identified in the last few years, they mainly involve expanding passive measures in a highly fragmented, categorical way. In political terms, the central Italian center-left part, the Democratic Party (PD), only recently embraced de-familializing measures without rejecting familializing ones. Indeed, it has the highest support for these measures among all the Social Democratic parties analyzed (Figure 5).

At the same time, the main, though declining, center-right party, Forza Italia (FI), has a solid familistic agenda while showing meager support for de-familializing measures (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2022). In other words, the institutional winners in Italy continue to be those with conservative positions regarding the family. Their support for the mainstream parties has declined considerably precisely because their votes in the 2013 and 2018 elections bolted to the 5 Stars Movement (M5S). This new challenger blurred its family policy positions, supporting a sort of implicit familialism, but managed to gain a widespread consensus due to its anti-establishment agenda.

The family policy institutions did not provide the League and FdI with an incentive to further radicalize the male-breadwinner policy agenda since there was no electoral void to be filled. On the contrary, a proposed agenda that includes some expansive measures regarding childcare and leaves helps gain the support of these institutional losers – primarily, working mothers – who, although more traditionalist, benefit from these programs. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the ESS data show female workers outnumber housewives within the Lega and FdI constituencies. Finally, similarly to AfD, within the FdI constituency, the ‘authoritarian alliance’, though majoritarian, is slightly weaker than the other RRPs. At the same time, the more libertarian group of managers represents a critical electoral group that could have further pushed the party to propose some de-familializing measures.

Conclusions

This paper investigated the radical right's family policy agenda in six western European countries. More specifically, drawing on the varieties of familialism and SI literature, it scrutinized the RRPs' positions on familialism and de-familialism, assessing whether it is possible to distinguish a radical right family agenda from those promoted by other party families. Furthermore, the RRP's positions on family policy and cross-country differences have been explained.

The content analysis of the party manifestos suggests that, on average, the RRPs adopt a radical male breadwinner policy agenda. This agenda is characterized by a high support for familialism and meager support for de-familialism, with the former much higher and the latter much lower than the other party families. This agenda has been explained by considering the RRP's specific electorate. The analysis of their constituencies shows a correlation between the electors' cultural attitudes toward family and the parties' family policy positions. In the case of the radical right, their constituency is more ‘authoritarian’ and less ‘libertarian’ than the median voter, pushing RRPs to strongly support familializing measures while disregarding de-familializing ones.

Notwithstanding the radical right's appearance as a reasonably cohesive party bloc, the empirical research has highlighted some cross-country differences, which were analyzed by considering the role of family policy institutions.

The analysis suggests that RRPs' family policy positions are informed by a counter-policy feedback. In countries where de-familialism has deep roots or a substantial change in this direction has been initiated, the RRPs have been further motivated to pursue a male-breadwinner policy agenda, as in the cases of the de-familialism countries, Scandinavia and Spain, where family policy institutions have created a group of institutional losers, for example, housewives and those with traditionalist values. Welfare institutions have thus provided the RRPs in these countries with a further electoral incentive to promote a male-breadwinner policy agenda to attract these institutional losers, which mainstream parties mostly have overlooked. Even in Austria and Germany, the RRPs have proposed a similar agenda, but they display slightly higher support for de-familialism. The expansion of de-familializing measures in these countries has not been followed by a radical cut of familializing policy instruments. The early institutional winners of the male-breadwinner model have not been turned into an ultimate loser group. They continue to be represented by the mainstream parties, although to a lower degree. The counter-policy feedback mechanism in these ‘optional familialism’ countries is thus slightly weaker compared to Sweden, Finland, and Spain.

In contrast, when familialism is well established in a country and de-familializing measures are poorly developed, RRPs will be less motivated to further radicalize the male-breadwinner agenda. Such is the case in Italy, where family policy continues to be characterized by a high degree of familialism. The institutional losers are those with libertarian preferences and living in dual-earner families, whose interests are barely represented by the mainstream parties. Family policy institutions thus do not reinforce the Lega and FdI's support for a male-breadwinner policy agenda since there is not an electoral void to be filled. For this reason, their support for de-familialism is the highest among the six cases analyzed. Proposing an agenda that includes some expansive measures regarding childcare and leaves would seem to be electorally useful.

The comparative empirical analysis prompts some final considerations.

First, the current study proves that the RRPs have a clear agenda regarding family policy. RRPs discuss family issues in post-material terms and by formulating specific programs with distributive implications. This finding, therefore, adds evidence to the recent literature that questions the position-blurring theory (see, Enggist and Pinggera, Reference Enggist and Pinggera2022). The radical right competes in the socio-cultural and the socio-economic dimension of the political conflict, whose positions are not blurred in this regard.

Second, RRPs' distributive positions are informed by post-material preferences. Their weak support for de-familialism and strong support for familialism are motivated by a desire to please their traditionalist electorate, which displays authoritarian inclinations regarding gender roles. This suggests that socio-economic and socio-cultural explanations of political actions are more interlinked than usually portrayed. For this reason, their interactions need to be investigated appropriately, especially when considering such a cross-dimensional issue as the family.

Third, the research shows that an institutional-based approach helps detect cross-country differences. In other words, institution matters, even for the radical right. However, they matter differently for these parties than the mainstream ones, at least when considering family policy. While this analysis does not present a precise causal mechanism, it suggests that counter-policy feedback mechanisms inform the RRPs' positions.

Future research can elaborate the findings of this research in a twofold way.

First, it would be interesting to broaden the scope of the comparison by including additional case studies and, at the same time, adopting a longitudinal analytical strategy.

Second, the focus could be narrowed by investigating more detailed specific case studies, as in the Italian case, where the counter-policy feedback mechanism functions differently than the other countries analyzed.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2022.23.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at: https://www.google.com/url?q=http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp&source=gmail-imap&ust=1656657918000000&usg=AOvVaw1rwoVuICen7NN7i-371RR1.