Introduction

The economic crisis triggered by the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic led European institutions to approve measures never seen before. Among these, the ‘Next Generation EU’ is certainly the most relevant one. Loans and grants are linked to the implementation of a complex plan with an impressive number of reforms and investments, which each Member State had to submit for approval to the EU Commission by May 2021: the so-called ‘National Recovery and Resilience Plan’ (NRRP), structured in various missions and components in different policy areas. To date, the Italian NRRP has been analysed in relation to its allocation of financial resources (Guidi and Moschella, Reference Guidi and Moschella2021) and its implications for the Italian political system as a whole (Moschella and Verzichelli, Reference Moschella and Verzichelli2021), as well as for what concerns the multi-level governance relations between national, subnational, and supranational institutions (Profeti and Baldi, Reference Profeti and Baldi2021; Domorenok and Guardiancich, Reference Domorenok and Guardiancich2022). As for how Italian interest groups played the ‘NRRP game’, Bitonti and colleagues (Bitonti et al., Reference Bitonti, Montalbano, Pritoni and Vicentini2021) focused on groups' media visibility as well as on the issues groups brought to the attention of public opinion. However, nothing has been said about groups' appreciation of policy contents in terms of their degree of preference attainment, which is a crucial research question in the lobbying academic literature (Leech, Reference Leech, Berry and Maisel2010).

Studying the formulation of the NRRP in Italy is important for at least two reasons. First, and practically, Italy has been one of the most hit countries by the Covid-19 pandemic and the EU Member State receiving the most loans and grants within the ‘Next Generation EU’ frameworkFootnote 1 (Domorenok and Guardiancich, Reference Domorenok and Guardiancich2022). Second, and theoretically, Italy experimented a change of government (from the second Conte cabinet to the Draghi cabinet in February 2021) precisely during the decision-making process leading to the formulation of the NRRP. Therefore, it is interesting to assess whether this political change had consequences on the contents of the plan and, linked to this, on the degree of interest groups' preference attainment. Thus, among the many analytical lenses that can be utilized to empirically study the formulation of the Italian NRRP, we decided to opt for an interest group perspective. On this, our justification is threefold. First, the European Commission suggested the greatest possible involvement of the main socio-economic stakeholders in the definition and implementation of the reforms linked to national plans (European Commission, 2021). Thus, focusing on these players appears as relevant and appropriate. Second, the Italian interest system greatly changed in recent years (Capano et al., Reference Capano, Lizzi and Pritoni2014; Lizzi and Pritoni, Reference Lizzi and Pritoni2017) and several authors argued that parties lost most of their role in structuring the policy process (Lizzi, Reference Lizzi2014; Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017b). Therefore, it is crucial to assess whether the dynamics characterizing the NRRP formulation can be reasonably inserted within this ‘big picture’ of change and party-group disentanglement or, on the contrary, government partisan composition still matters for interest groups' preference attainment. Third, to the best of our knowledge in no European country has the role of national interest groups in defining the NRRP been empirically analysed to date: our contribution could therefore pave the way for more numerous and systematic analyses in the future.

Thus, this article focuses on how the 20 main Italian interest groups evaluated the design of the Italian NRRP. More precisely, in comparing its two versions (Conte Draft and Draghi Plan) with the aim of assessing the role of government partisan characteristics for interest groups' preference attainment, we tackle two main research questions: has the Italian interest groups' general appraisal increased or decreased? Did the configuration of interests that appreciate the Plan change? To do so, we rely on a vast empirical material, collected through both quantitative and qualitative research methods. First, we coded about 800 public statements provided by the 20 main Italian interest groups in two different periods: between 12 January and 11 February 2021 (to empirically analyse groups' reactions to the elaboration of the ‘Conte Draft’, which was approved in the Council of Ministers on 11 January 2021); and between 25 April and 31 May 2021 (to empirically analyse groups' reactions to the elaboration of the ‘Draghi Plan’, which was presented to the Italian Parliament on 24 April 2021). This dataset takes into account different communication channels: one of the two most diffuse national newspapers – ‘la Repubblica’ – plus all webpages, Facebook pages and Twitter accounts of analysed interest groups. Second, we conducted an additional qualitative analysis through nine semi-structured interviews: eight with interest groups' executives and one with the former Chief of Staff at the Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri with the Prime Minister Mario Draghi. Taken together, the quantitative dataset and the qualitative interviews allow to trace a recognition of how and to what extent the most important Italian interest groups appreciate the formulation of a multi-year plan of reforms and investments.

Yet, two limits to our research should be highlighted. First, it is necessary to consider the exceptionality of the policy process analysed here: the elaboration of the NRRP probably has no equal in the history of the Italian RepublicFootnote 2. It is not possible, therefore, to draw generalizations that go beyond the case itself. Second, we use the so-called ‘organisational definition’ of interest group instead of the alternative ‘behavioural definition’ (Chalmers et al., Reference Chalmers, Puglisi, Van den Broek, Harris, Bitonti, Fleisher and Binderkrantz2022). In the former case, only membership organizations are considered as interest groups, whereas in the latter, so are individual firms, institutions and, more generally, any decisional actor who lobbies legislators to reach policy outputs. We are aware that the ‘NRRP game’ did not see the lobbying mobilization of membership organizations only, but of individual firms and institutions as well. This means that our empirical reconstruction is only partial and cannot say anything about the role of big companies – i.e., ENI, Trenitalia or ENEL, among the others – who had interests at stake in the policy process under analysis and, presumably, put pressure on policymakers to see their requests transformed into public policies.

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the main literature to which our work contributes and presents our analytical framework, while the third section illustrates the research design. The fourth section presents the most general empirical results of the quali-quantitative analysis conducted, both with regard to the governance of the NRRP and to the interest groups' appraisal of its main policy contents. Section 5 goes into greater depth, focusing on the components of the NRRP and assessing the degree of preference attainment of the different groups investigated. Finally, Section 6 discusses empirical findings and presents potential trajectories for future research.

Literature review and theoretical expectations

The problem of interest groups' influence in policymaking is a long-standing and paramount puzzle for scholars in lobbying studies. The relevance of influence for understanding the role of interest groups in political systems is as high as the hurdles in explaining and measuring it (Dür and de Bièvre, Reference Dür and de Bièvre2007). A range of approaches has been developed and tested in the literature, which looked at both actor-centred and contextual determinants for influence through the adoption of quantitative and qualitative techniques across different stages of the policy cycle (Beyers, Reference Beyers, Harris, Bitonti, Fleisher and Binderkrantz2022).

To empirically assess the interaction between interest groups' resources, policymakers' preferences and policy issue characteristics in shaping lobbying capacity, the recent literature increasingly focused on the conceptualization of influence as ‘control over policy outputs’ (Dür and de Bièvre, Reference Dür and de Bièvre2007, 3), generally following the so-called ‘preference attainment approach’ (Vannoni and Dür, Reference Vannoni and Dür2017). However, ‘control over policy outputs’ and ‘preference attainment’ should not be considered synonymous: the concept of ‘control’ logically implies that groups exert actual influence to push policy decisions in a desired direction. Differently, the concept of ‘preference attainment’ does not distinguish actors that pulled the strings in the lobbying process from actors that benefited from the actions of other players. In this work, we prudentially prefer to talk about preference attainment (and, in turn, policy success) instead of actual policy influenceFootnote 3. Such an approach still allows scholars to operationalize and measure lobbying success for empirical analysis by answering the fundamental question about who gets what in the policymaking, shedding light on the core preference cleavages, the sensitive issues at stake and the final count of winners and losers.

From a theoretical point of view, the recent literature on the EU and Western European countries alternatively or complementarily sheds light on the explanatory potential of (i) organizational and relational resources (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015; Kohler-Koch et al., Reference Kohler-Koch, Kotzian and Quittkat2017), (ii) policy issues' characteristics (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2012; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014), and (iii) ideological proximity between interest groups and policymakers (Røed, Reference Røed2022; Reference Røed2023), to understand interest groups' varying degrees of preference attainment. More precisely, both organizational and relational resources (namely, the size of membership, representativeness, economic and financial resources, expertize and reputation), as well as ideological proximityFootnote 4, should be direct predictors of policy success, following a classic ‘the more, the more’ logic. On the other side, political salienceFootnote 5 should favour public interest groups, while highly technical and complex policy issues should represent the best battlegrounds for business groups and professional associations.

From this angulation, Italy fits quite well with such a European research strand. While interest groups' lobbying in Italy has long been neglected by the political science community (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2016), in the last decade a burgeoning empirical literature is contributing to catching up with the European and international debate (Montalbano and Pritoni, Reference Montalbano, Pritoni, Polk and Mause2022). Most of the empirical works on Italian interest groups have built on preference attainment analysis to evaluate who won and who lost in the lobbying battles across a variety of key policy initiatives, especially focusing on the decision-making moment (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2015, Reference Pritoni2017b; Lizzi and Pritoni, Reference Lizzi and Pritoni2019). The results obtained from these works offer a comprehensive picture of the recent lobbying patterns in Italy, together with the key conditions which likely enabled (or prevented) interest groups' policy success, which can guide our subsequent analysis.

First, recent studies ascertained business groups' capacity to get their demands broadly realized in the policymaking when it comes to highly technical and low salient issues. The cases of complementary pensions promoted by the second and third Berlusconi cabinets (2005), together with the reform of health governance by the Monti government (2012), showed how the use of expertize in a context of low public salience ensured business groups' policy success (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017b). Conversely, banking and insurance firms' interests suffered a substantive defeat under the liberalization reforms promoted by the Prodi government (2006) and in the Monti ‘Save Italy decree’ (2012), when public interest groups (namely, consumer organizations) stood out as increasingly influential actors (ibidem, 106–107). In the latter case, in particular, the public attention on the financial sector after the global financial crisis in 2008 hampered the influence capacity of bankers and insurers, while increasing public interests' chances of success (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2015). However, as the salience of financial regulation faded away, corporate groups regained clout, as it has been assessed in the case of the attempted reform of the insurance sector in 2017 (Germano, Reference Germano2023). Such results seem to confirm an inverse relationship between policy issue salience and business interests' influence (Montalbano, Reference Montalbano2021).

Yet, contrary to such argument, Italian entrepreneurial groups were able to shape the reform process even in case of salient issues. Berlusconi's school reform represented a salient and contested reform in which business appeared to gain the most (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017b, 110–111). In this case, a high level of ideological proximity between such groups and Berlusconi cabinet countered the pressures coming from public issue salience, playing a relevant role in ensuring business influence. This latter case is particularly interesting, because it seems to contradict the idea, repeatedly argued in the recent literature, that Italian political parties have largely lost their role as policy gatekeepers (Lizzi, Reference Lizzi2014; Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017b, Reference Pritoni2019), and therefore their ideological orientations no longer matter that much for interest groups' chances to reach policy results.

As far as government's political characteristics are concerned, many of the abovementioned works highlighted as well the importance of the decision-making capacity of the cabinet (that is, the capacity to get the reform outputs without much opposition by the Parliament) (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017a) for interest groups' chances of success. Pritoni (Reference Pritoni2017b) showed that the larger the decision-making capacity of the government, the less would be interest groups' policy success, as groups cannot fully exploit the parliamentary debate to push ahead with their demands. Governments able to follow a strategy of ‘disintermediation’ (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2014) may thus impose their own policy agenda, in so restricting interest groups' room for manoeuvre.

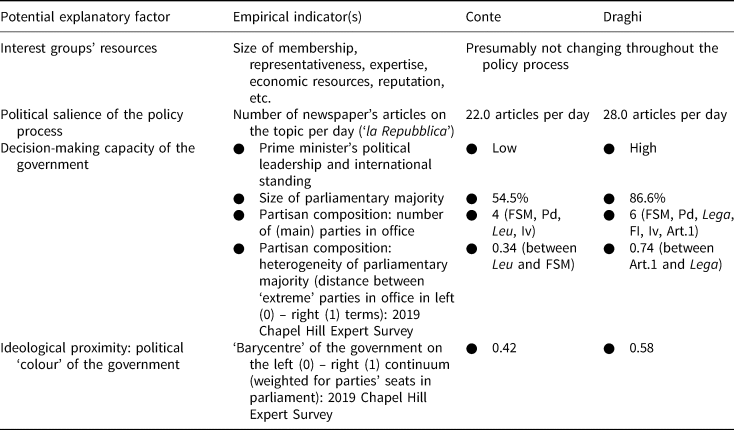

In the end, according to the reviewed literature, the degree of political salience and technical complexity, combined with the features of the government – i.e., its decision-making capacity and its partisan composition (and, in turn, ideological orientation) – emerge as key factors in shaping interest groups' preference attainment in Italy. However, while on the role of issues' characteristics there is a substantial academic consensus, the importance of party-group ideological proximity for interest groups' preference attainment in the policymaking is more controversial (Lizzi, Reference Lizzi2014). All this makes the formulation of the Italian NRRP a crucial case to be studied. While neither groups' resources, on the one hand, nor political salienceFootnote 6, on the other, changed that much throughout the decision-making process, the fact that the composition of the political actor leading the policymaking did (i.e., from the so-called ‘yellow-red’ coalition formed by Five Star Movement (FSM), Democratic Party (Pd), Liberi e Uguali and Italia Viva, sustaining the second Conte government, to the grand coalition sustaining the Draghi government) represents a potentially very interesting factor to explore in accounting for interest groups' stances and preference attainment on the contents of the NRRP design (Table 1).

Table 1. Potential explanatory factors of interest groups' degree of preference attainment from Conte to Draghi

Notes: Total number of articles on the NRRP from September 16, 2020 to January 11, 2021 (Conte period: 117 days): 2568; total number of articles on the NRRP from January 12, 2021 to April 24, 2021 (Draghi period: 102 days): 2860.

Source: authors' elaboration.

As for the decision-making capacity of the government(s), we have mixed expectations. On the one hand, what has been defined as a weak and quarrelsome executive (Marangoni and Kreppel, Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022) has been replaced by another enjoying a very large parliamentary majority and led by a prime minister with clear political leadership and international standing (Capano and Sandri, Reference Capano and Sandri2022). Moreover, time constraints and EU pressures on the NRRP approval speeded up and tightened the decision-making process at the governmental level. This should lead to hypothesize that the room for manoeuvre at disposal of interest groups, during the decision-making process, has probably narrowed, thus diminishing the general degree of interest groups' appraisalFootnote 7 of the Draghi Plan in comparison to the Conte Draft (Hypothesis 1a). However, the new government is formed by more parties, which are also (much) more politically heterogeneous from one another. This might have an impact on the decision-making capacity of the government, actually lowering it (Pritoni, Reference Pritoni2017a). Moreover, as the governmental majority became more variegated, the range of social interests having presumable access to policymakers (and, in turn, being able to reach policy resultsFootnote 8) should be broader in the case of the Draghi cabinet.

Yet, this latter theoretical expectation is valid only under the assumptions that between (Italian) parties and interest groups an actual ideological proximity existed, as well as that parties' representatives were capable to influence the contents of the NRRP within the meaningful loci of the decision-making process. If this is the case, in fact, the analysis of distributive policies (as the NRRP certainly is) should see the appraisal of more policy measures by more interest groupsFootnote 9. In other words, a broader range of interests should approve the Draghi Plan when compared to the Conte Draft, thus increasing interest groups' general appraisal of the NRRP (Hypothesis 1b).

Whether or not (Italian) political parties and interest groups are (more or less) ideologically proximate should also impact on the identity of groups appreciating the Conte Draft while disapproving the Draghi Plan, and vice versa. If (Italian) parties and interest groups are largely disconnected and, therefore, ideological proximity does not matter for interest groups' chances of advocating policy results, the change in the parliamentary majority and the related government composition should have no impact on the type of interests enjoying high degrees of preference attainment (Hypothesis 2a). On the contrary, if party-group ideological proximity matters and political parties within the government retain their influence on the NRRP formulation, the configuration of interest groups appreciating the contents of the NRRP should vary during the decision-making process, to the advantage of business groups (Hypothesis 2b). This depends on the change of partisan composition within the parliamentary majority supporting the government, and reflected in the policy relevant ministries, with the political ‘centre of gravity’ of the executive more shifted towards the right of the political spectrum. Indeed, the ideological proximity between right-wing parties and business associations has been variously demonstrated in the literature, while the same holds between left-wing parties and labour unions and public interest groupsFootnote 10. In a nutshell, only if the change in government partisan composition matters for the contents of the NRRP and, in turn, for interest groups' preferences on those same (changing?) contents, we should expect an increasing general appraisal of the Plan and a growing degree of preference attainment for business groups passing from Conte to Draghi. Otherwise, we should not detect any appreciable differences in interest groups' stances about Conte Draft and Draghi Plan (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analytical framework.

To summarize, we develop a within-case longitudinal comparison that is theoretically crucial in at least two respects. First, it can help assess the relevance of ideological proximity for interest groups' preference attainment (at least, in the case under scrutiny). Second, it can help add empirical evidence to a topic that, in recent literature, has regained momentum: that of ideological proximity and policy alignment between groups and parties (Allern et al., Reference Allern, Hansen, Marshall, Rasmussen and Webb2021a, Reference Allern, Hansen, Otjes, Rasmussen, Røed and Bale2021b, Reference Allern, Wøien Hansen, Rødland, Røed, Klüver, Le Gall, Marshall, Otjes, Poguntke, Rasmussen, Saurugger and Witko2023). The international literature, on this point, has shown contradictory empirical results (Otjes and Rasmussen, Reference Otjes and Rasmussen2017; Røed Reference Røed2022), and the Italian case is no exception (Lizzi, Reference Lizzi2014). Therefore, it becomes relevant to assess the correspondence between the change in the political colour of the executive, on the one hand, and the change in interests (not) appreciating the contents of the Plan, on the other.

Research design

Our analysis relies on a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, concerning the positions of the main Italian interest groups, on the one hand, and the two versions of the Italian NRRP, on the other hand. This is because we want to give an empirical answer to two fundamental research questions, which are as follows: when comparing Conte Draft and Draghi Plan, did the Italian interest groups' general appraisal increase or decrease/remain stable? Did the configuration of interests that appreciate the Plan change? Answering these questions will help assess the importance of ideological proximity for Italian interest groups' preference attainment.

To identify interest groups to be included in our analysis, in line with previous studies on the Italian case (Lizzi and Pritoni, Reference Lizzi and Pritoni2017; Bitonti et al., Reference Bitonti, Montalbano, Pritoni and Vicentini2021), we used two criteria: the ‘public visibility’ of groups, looking at their presence in the media, and more specifically in national daily newspapersFootnote 11; their level of access to the governmental arena, more specifically looking at what groups were officially invited by the designated President of the Council of Ministers, Mario Draghi, in the consultations held in Palazzo Chigi before the beginning of his office on February 10, 2021. By combining these two criteria, we could identify the twenty main Italian interest groups, resulting in a rather comprehensive list including labour unions (CGIL, CISL, UGL, UIL), business associations (ABI, Alleanza delle Cooperative, ANCE, ANIA, Confapi, Confartigianato, Confcommercio, Confesercenti, Confindustria, Unioncamere), institutional groups (ANCI), occupational associations (Coldiretti), and public interest groups (Emergency, Greenpeace Italia, Legambiente, WWF Italia). As already claimed, our focus is on membership organizations only.

We then proceeded to build a dataset of all public statements of such groups concerning the NRRP (through a keyword search, including also different labels, such as ‘Recovery Fund’ or ‘Recovery Plan’), analysing four different media sources: (i) interest groups' own websites; (ii) interest groups' Twitter accounts; (iii) interest groups' Facebook pages; (iv) interest groups' statements reported in the articles published by the newspaper ‘la Repubblica’Footnote 12. We covered the time lapses following the publication of the two versions of the Plan, retrieving all the statements produced between 12 January and 11 February 2021, immediately after the so-called ‘Conte Draft’ (approved in the Council of Ministers on 11 January 2021), and between 25 April and 31 May 2021, immediately after the publication of the final ‘Draghi Plan’ (presented to the Italian Parliament on 24 April 2021). We therefore ended up with a dataset of 769 public statements: 473 on the Conte Draft and 296 on the Draghi Plan (Table 2).

Table 2. Interest groups public statements (websites, Facebook, Twitter, la Repubblica)

Source: authors' original dataset.

All public statements have been coded looking at different variables: (a) whether the statement referred to the NRRP in genericFootnote 13 or specific termsFootnote 14; (b) whether the statement concerned its actual policy content or governance mechanisms; (c) the degree of groups' approval on the abovementioned elements, with a range of different options from ‘strong opposition’ to ‘strong support’Footnote 15. The inter-coder reliability of the coding process for all the variables of every statement was tested through a double coding of 10% of the entire dataset, with a Cohen's kappa of 0.93.

To further strengthen the empirical base of our work, we also relied on nine semi-structured interviews: eight with the top executives of some of the interest groups under analysis and one with the former Chief of Staff at the Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri with the Prime Minister Mario Draghi (the interviews were held between May 2021 and November 2022: see the Online Appendix for further details). Interviews have been especially useful to shed additional light on the levels of preference attainment achieved by the groups in the drafting of the two plans, as well as on the loci of interest groups' mobilization and interaction with political parties.

When analysing policymaking from an interest group perspective, the preference attainment approach is increasingly seen as a useful and promising approach (Vannoni and Dür, Reference Vannoni and Dür2017). That is why we chose this approach to engage in a qualitative analysis of the text of the two versions of the NRRP, and highlight all the cases of visible overlap between the design in the two versions and the specific statements of any of the interest groups analysed. More precisely, we focused on the explicit political aims of each component to verify whether they changed between the first and the final version, as well as whether those same (potential) changes reflected some group's public preferences. On the contrary, we do not focus on structural reforms contained in the first part of the Plan and on chrono-programmes in the final part: this is because both were largely absent in the Conte Draft, which was precisely a preliminary draft. Thus, our approach differs from previous analyses of the (more or less) changing contents of the Italian NRRP in its two versions, which focused on the financial allocation of resources, as well as on the number of words dedicated to different policy reforms and investments within missions and components (Guidi and Moschella, Reference Guidi and Moschella2021).

From Conte to Draghi: interest groups' general appraisal of the two plans

To start answering our research questions, we first sorted interest groups according to their type, grouping business associations (ABI, Alleanza delle Cooperative, ANCE, ANIA, Confapi, Confartigianato, Confcommercio, Confesercenti, Confindustria, Unioncamere), public interest groups (Emergency, Greenpeace Italia, Legambiente, WWF Italia), unions (CGIL, CISL, UGL, UIL), and others (ANCI as an institutional group and Coldiretti as an occupational association). Second, we calculated the number of all positive and negative statements (on the formulation of the NRRP in its two versions) of all groups according to the focus of each statement (statements concerning the governance of the Plan; generic statements on the Plan; statements on specific aspects of the Plan), weighing the expression of strong support (+1) or opposition (−1), and the expression of mild support (+0.5) or opposition (−0.5). To better read data, we turned all the results into percentage values (with +100 representing maximum appreciation, and −100 representing maximum disfavour), as the following formula explains (Table 3):

Table 3. Interest groups' support for or opposition to the two versions of the Italian NRRP

Source: authors' elaboration.

As far as the governance of the NRRP is concerned, all types of groups expressed overall quite negative stances, in both timeframes under analysis. However, this happens with different intensity for the various categories of groups, and with some remarkable changes between the two periods. Whilst the unions quite stably maintain their moderately negative stance on the governance of the Plan in both cases, Draghi Plan induced a better (while still generally negative) stance from business groups, and a steep rise in public interest groups' discontent (slightly negative on Conte Draft, extremely negative on Draghi Plan). A somewhat different pattern can be spotted when looking at the generic statements on the two versions of the Plan. Business groups turn from being very strongly negative on Conte Draft (−81.3) to being decisively positive on Draghi Plan (+62.5), with unions somewhat appreciating Conte Draft (+16.7) and being moderately negative on Draghi Plan (−25.0), and with public interest groups expressing their negative stance on Conte Draft (−66.7), but worsening it with Draghi Plan (−85.7). Remarkably, other interest groups (ANCI and Coldiretti) pass from a balanced position on Conte Draft (0.0) to the highest level of support for Draghi Plan (+100.0).

Finally, when it comes to statements on specific aspects of the Plan, both business groups and public interest groups express greater appreciation for Draghi Plan than for Conte Draft, even if public interest groups maintain a negative attitude towards both, while business groups turn from being definitely negative on the former (−47.0) to being quite positive towards the latter (+35.0). On the other hand, both unions and other groups see lower levels of support for Draghi Plan than for Conte Draft (with other groups passing from a quite positive stance on Conte Draft to a rather negative stance on Draghi Plan).

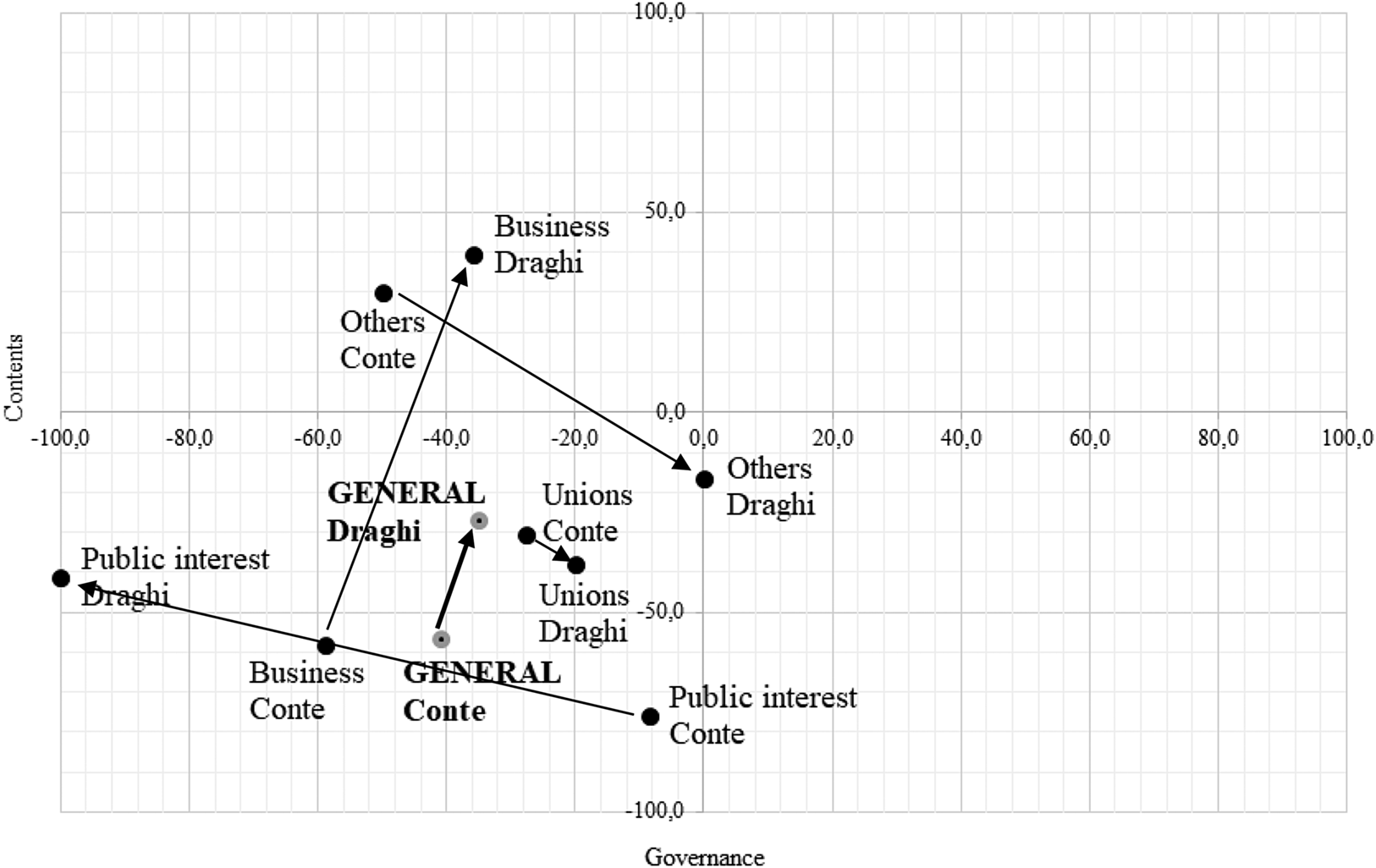

To provide a better visual overview of the general attitudes of groups on the two versions of the NRRP, concerning both its governance and its content (the latter deriving from all generic and specific statements considered together), we created an area plot (Figure 2), with the degree of appraisal on the governance of the NRRP on the X axis, the degree of appraisal of its contents on the Y axis, and various types of groups (concerning both versions of the NRRP) being represented by the dots in the quadrants.

Figure 2. Support or opposition of the various categories of interest groups: Conte Draft and Draghi Plan compared.

Source: authors' elaboration.

The ‘quadrant of discontents’ (where negative stances on both governance and contents are located) is quite crowded, with only two dots out of eight being in a different quadrant. All the considered interest groups seem to express varying degrees of dissatisfaction with the governance mechanisms of the NRRP, and a similar stance can be highlighted also with regard to the contents of the two versions of the NRRP, with the notable exception of business groups, appreciating Draghi Plan (while disliking Conte Draft). Overall, the ‘general dot’, showing the appraisal of interest groups for both governance mechanisms and policy contents, moves higher (enhancement on the axis of policy content) and to the right (enhancement on the axis of governance mechanisms) in comparing Conte Draft to Draghi Plan. Moreover, the individual dot that most rises and goes to the right is that of business groups. Taken together, those empirical findings appear as a first preliminary confirmation of Hypothesis 1b and Hypothesis 2b. Yet, to better clarify groups' stances and respective preference attainment, the next section proposes a more detailed analysis of some of the issues tackled by the various missions (and, especially, components within missions).

From Conte to Draghi: what changed and who got what?

As the preliminary condition to set the contents and follow their implementation, the governance and participatory framework of Italy's NRRP represented the first issue for interest groups here considered. On this, the Conte Draft received little appreciation from the main labour and business organizations, the ones who mostly pressured the government to be systematically involved in defining the governance mechanisms of the NRRP. More precisely, Confindustria expressed the most critical stance, while the two largest unions (CGIL and CISL), together with Confcommercio, gave a rather negative opinion on the functioning and prospects of the governance framework. Both the main Italian business and workers' organizations complained about the poor involvement of social partners and relaunched on the need for a shared ‘control room’ (Interview Confindustria 2021; Interview CGIL 2021; Interview CISL 2021). Focusing on the implementation stages, environmental associations questioned the adequacy of the NRRP governance system in ensuring compliance with the International and European commitments on the ecological transition (Interview Greenpeace Italia 2021).

Interest groups' views on the NRRP governance process slightly changed in front of the Draghi Plan. The major business, workers and public interest groups here considered largely agreed in pointing at the general lack of an adequate consultation framework in the policy-definition phase, while expressing concerns about an appropriate involvement at the subsequent implementation stages (Interview Confartigianato 2021; Interview CGIL 2021; Interview CISL 2021; Interview Legambiente 2021; Interview Greenpeace Italia 2021). Some groups, however, recognized at least the government's availability to hear their main priorities for the NRRP, while blaming its occasional and non-systematic character (Interview Confindustria 2021; Interview Confartigianato 2021; Interview Greenpeace Italia 2021). Just a few business organizations expressed satisfaction with their involvement in the agenda-setting stage (Interview ANCE 2021). Yet, different groups' representatives mentioned the maintenance of communication channels with the relevant ministries throughout the process, as the informal venue to deliver policy demands and inputs, whereas the formal moments of confrontation with Palazzo Chigi were judged insufficient (Interview Coldiretti 2021; Interview Confindustria 2021; Interview UIL 2021; Interview Legambiente 2021; Interview ANCE 2021). Moreover, ministries have been tasked with dealing with the revision and final definition of the NRRP missions' components and objectives, with the government ‘control room’ at the Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri remaining in charge of the chrono-programs, the enabling reforms and the general coordination of the Plan (Interview former Chief of Staff at the Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2022).

The picture is rather more varied when looking at policy contents. Even in this case, the Conte Draft generally received a cold welcome from interest groups in our sample. The most contested NRRP components were those linked to the ‘green transition’ chapter, followed at a distance by labour, social and cohesion policies, mirroring both the expected entity of resources at stake and the activism of business and public interest groups on those issues.

First, conflicting views emerged between unions and business representatives. While the three main unions pointed to the inadequacy of measures concerning job creation and safeguards, Confindustria's criticisms turned to the priority given to Public Employment Centres while relaunching the need for public-private partnerships in workers' formation and job placement services. Significant contrasts emerged as well between unions and environmental associations on NRRP green investments. In particular, a heated debate broke out on the NRRP funding of a plant for carbon capture and storage sponsored by ENI, the main Italian energy company. While the three environmental organizations openly praised the exclusion of the ENI-sponsored project from the draft text of the plan, in a joint document, CGIL, CISL and UIL blamed such a choice as a loss of job creation opportunities and missed investment to prompt the ecological transition. The interventions and resources related to the NRRP sustainability chapter attracted as well the criticisms from the financial and industrial sectors. While generally praising the rationale and resources devoted to the measure (Interview ANCE 2021), business groups called for extending the timeline and application of the environmental bonus for the renewal of buildings, as the plan objective attracting the largest amount of resources. From a different perspective, Legambiente and CGIL called for a redefinition of the eligibility criteria for such ecological bonuses, to prevent the exclusion of poor households (Interview Legambiente 2021). Environmental groups, on the other side, pointed to the failure to update the national plan for energy and climate in line with the recent decarbonization commitments adopted within the UN framework, thus failing to define adequate interventions and investments in the NRRP green chapter. Similarly, a joint letter promoted by WWF and signed by 14 organizations and experts denounced the lack of investments dedicated to the preservation of natural ecosystems and biodiversity. The interventions on sustainable agriculture and urban mobility represented another contentious point, with public interest groups complaining about the lack of resources allocated to them, while a division emerged within the same environmentalist world on the support of bio-methane plants (Interview Greenpeace Italia 2021; Interview Legambiente 2021).

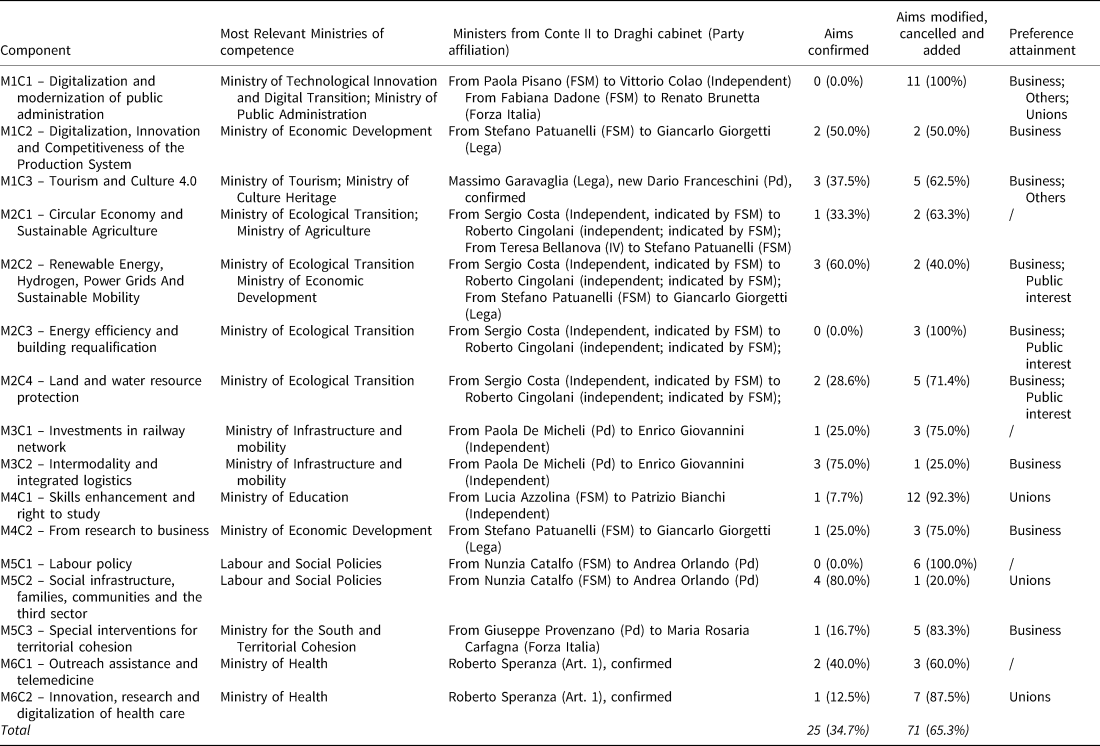

If we compare Conte Draft to Draghi Plan, we notice some significant changes in the formulation of the main objectives for each of its components (Table 4). Not by chance, most of these reformulations coincided with the components of the Conte Draft that received most of the criticism from interest groups and/or for which the minister in charge changed from the second Conte cabinet to the Draghi cabinet.

Table 4. Changing political aims for each component: Conte Draft and Draghi Plan compared

Source: authors' elaboration.

Looking at the appraisal of the final NRRP design (Draghi Plan), we can observe which interest groups saw their preferences mostly reflected in the components' main political aims, which in the Plan are openly claimed at the beginning of each component. Positive evaluations have been given by different business actors, unions, and public interest groups, each one claiming at least to have achieved some significant results on the respective themes. However, some of them, particularly business interests, expressed strong satisfaction. The national association of building entrepreneurs, for example, stressed how about half of the 222 billion worth NRRP was of interest to the sector, while explicitly claiming the paternity of the proposal regarding the eco-bonus for building renewal (Interview ANCE 2021). Positive assessments were also given by Confartigianato with respect to digital transition and the eco-bonus for Italian SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprizes), as well as by Confindustria, who expressed satisfaction in particular for the planned reforms of Public Administration and Justice. Yet, for business interests a major unsolved issue was the extension of the eco-bonus time window up to 2021 (further raised by ABI, Confindustria and ANCE). Finally, small business and commercial associations appreciated the measures on the internationalization of enterprizesFootnote 16 while asking to accelerate the efforts to restore the pre-crisis level of exportations; just like Confcommercio, who stressed, on the contrary, the need for further resources on the sustainable shipping sector, urban mobility, and inter-modality.

Even the environmental groups publicly praised the government for having confirmed the exclusion of the contested ENI-sponsored gas plants, while maintaining the funding to biogas plants and the development of energy communities (Interview Legambiente 2021). On the same page, WWF claimed the inclusion of the project, elaborated jointly with Confindustria, on the renaturation of the Po river and environmental restoration. However, most of the environmentalists' positive comments on the final plan stressed the limited scope of the interventions and inadequacy of programmed resources, like in the investments in Agri-voltaic systems, and generally on renewable plants, as well as on the circular economy, sustainable agriculture and the protection of biodiversity (Interview Greenpeace Italia 2021).

Mixed reactions also came from unions, who generally praised the government for confirming the job creation objectives to be linked to the NRRP investments and the cross-cutting targeting of Southern Italy, young people and women, which was claimed as a relevant achievement (Interview CGIL 2021; Interview CISL 2021). Moreover, the three main unions expressed open satisfaction with the acceptance in the NRRP of the joint proposal for a framework law on dependent people, the strengthening of Public Employment Services, and the investments in the school sector. Yet, such positive comments paired with criticisms on the size of allocated resources to labour and social policies, as well as the incertitude for concrete compliance with the NRRP objectives (Interview CGIL 2021; Interview CISL 2021). Similar concerns for the plan's implementation prospects, particularly regarding the streamlining of bureaucracy, were raised by the association of Italian municipalities (ANCI), who, on the other side, declared that the ‘themes advanced by the Italian mayors’ were ‘all included in the NRRP’.

Overall, while the allocation of economic and financial resources to each mission and component did not change that much between Conte Draft and Draghi Plan (Guidi and Moschella, Reference Guidi and Moschella2021), the same does not hold for explicit political aims representing the core objectives of each component of the NRRP, which have been defined within the relevant ministries (Interview former Chief of Staff at Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri 2022). Some of these aims changed only incrementally, whereas others have been cancelled and/or added between the first and the final version of the NRRP, in some cases following the requests of some interest groups and in other cases at the expenses of other groups' instances. Our empirical analysis seems to suggest that many groups can be satisfied with at least one of those changes. However, the degree of preference attainment of various types of groups is clearly different, as well as it differs if we look either at Conte Draft or Draghi Plan. More precisely, business groups seem to have greatly improved their position, appreciating policy measuresFootnote 17 and governance mechanisms much more in the final version of the NRRP than it was in the draft approved by the ‘yellow-red’ majority sustaining the second Conte government. On this, ministers responsible for refining missions and components of the Plan – and, in particular, their changing partisan affiliation – appeared rather relevant.

Discussion of the findings and future research

We structured this article around two research questions: the first was about the general level of interest groups' appraisal for the two versions (Conte Draft and Draghi Plan) of the Italian NRRP, while the second focused on the (changing) nature of interest groups appreciating its governance mechanisms and policy design. We collected interesting empirical evidence to start answering both questions.

First, the general degree of appraisal for the formulation of the NRRP increased from Conte to Draghi, in so confirming Hypothesis 1b while rejecting Hypothesis 1a. The previous ‘yellow-red majority’ dissolved precisely because of different visions regarding the writing of the NRRP (Marangoni and Kreppel, Reference Marangoni and Kreppel2022), and thus in February 2021 the Draghi government took office. The latter is supported in Parliament – in addition to the Five Star Movement, the Democratic Party, Liberi e Uguali and Italia Viva – also by Forza Italia and Lega. The fact that the Draghi cabinet is supported by more numerous and heterogeneous parties implies the broadening of the range of economic and social interests with easy access to policymakers and, in turn, an increase in the number and heterogeneity of interest groups that can be satisfied by distributive policy measures approved by the government.

Second, interest groups appreciating Conte Draft are different from interest groups appreciating Draghi Plan. More precisely, the balance between different interests at stake shifted in favour of the business community and to the detriment of environmental associations (especially with respect to governance mechanisms), with labour unions and other groups not changing their judgement that much in passing from the first to the final version of the NRRP. This can be claimed both if we look at the ‘big picture’ of all public statements, as well as if we focus more in depth on each component's political aims. All this seems to give empirical support to the hypothesis claiming the relevance of party-group ideological proximity for interest groups' preference attainment (Hypothesis 2b). All else being equal (i.e., groups' resources and policy characteristics), the greater ideological proximity between business interests and the new executive is the most likely factor to account for the increased degree of preference attainment (and overall satisfaction with the NRRP) shown by this type of interests. Indeed, a recent study (Lisi, Reference Lisi2022, 109) empirically demonstrated how Lega and Forza Italia are ideologically proximate to business associations (i.e., Confindustria and Confcommercio) and electoral studies recognize that both right-wing parties are generally more voted by self-employed as well as by small and big entrepreneurs (Comodo and Forni, Reference Comodo, Forni, Valbruzzi and Vignati2018, 215), in so showing a great deal of ideological proximity with business groups in giving representation to interests present in society. Moreover, the ideological proximity argument is reinforced by the role played by the relevant ministries in the definition of the NRRP components and objectives, representing a critical venue for the interaction between interest groups and parties. Taken together, our two main empirical findings stand for a renewed centrality of party-group ideological proximity in Italy, thus representing the main analytical added value of the research conducted.

Yet, our contribution only scratches the surface of an empirical analysis that should continue in the close future. More precisely, we see (at least) four potential directions for future research. First, Italy is not the only EU country that experimented a change of government during the policy process leading to the formulation of the NRRP. The same happened in BelgiumFootnote 18, as well as in various Eastern European countries: EstoniaFootnote 19, LithuaniaFootnote 20, RomaniaFootnote 21 and SlovakiaFootnote 22. There is fruitful analytical space to empirically test the explanatory potential of ideological proximity for interest groups' preference attainment in a comparative perspective, in particular with regard to Eastern Europe, where the study of interest groups and lobbying is gaining momentum after years of scarce empirical analysis (Czarnecki and Piotrowska, Reference Czarnecki and Piotrowska2021).

Second, our multi-media strategy to collect interest groups' official stances on the design of the Italian NRRP might be further broadened. In particular, we focused exclusively on the newspaper ‘la Repubblica’: it would be interesting to verify whether other national newspapers gave different media coverage to different interest groups, in so potentially adjusting our empirical results.

Third, while we collected insights of interest groups' preference attainment mainly in the agenda-setting stage, nothing has been said on the actual design of policies. Following a genuine policy design perspective would be fundamental to assess winners and losers of the decision-making: this would imply focusing on a few crucial reforms with regard to their specific adopted policy instruments. Indeed, policy instruments are pivotal in policy design and can be considered the core of policymaking (Capano and Howlett, Reference Capano and Howlett2020). Thus, assessing what interest group pushed for what policy instrument would greatly enhance our understanding of policy dynamics and would return a clearer picture of the ‘lobbying battle’ among different kinds of interests.

Fourth, interest groups not successful or marginalized in the earlier stages of the policymaking may take action in the following ones and pursue their policy objectives by affecting implementation (Capano and Pritoni, Reference Capano, Pritoni, Harris, Bitonti, Fleisher and Binderkrantz2022). Thus, to provide a proper analysis of the effective role of different types of groups, extensive research of the implementation processes of the NRRP will be required.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.7

Data

The replication dataset is available at: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/OX77DM

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments on the original version of this article: they greatly increased the quality of the work done.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.