Introduction

Provision of early intervention services (EIS) for psychotic illness now holds a central position in mental health care. This primacy derives from meta-analytic evidence across 13 indices of outcome in 10 randomised clinical trials (Correll et al. Reference Correll, Galling, Pawar, Krivko, Bonetto and Ruggeri2018), supplemented by evidence for reduced risk for suicide (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Chan, Pang, Yan, Hui, Chang, Lee and Chen2018) and judicial outcome (Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Ferrara, Lin, Kucukgoncu, Wasser, Li and Srihari2020). In the real-world setting of the Irish public health services, longer durations of untreated psychosis and of untreated illness are associated with increasing impairment (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a) and we have recently reported health economic advantage for EIS using the net benefit approach (Behan et al. Reference Behan, Kennelly, Roche, Renwick, Masterson, Lyne, O’Donoghue, Waddington, McDonough, McCrone and Clarke2020).

The journey to EIS in Ireland has been authoritatively reviewed by Power (Reference Power2019). Establishment of DETECT in 2007 (Omer et al. Reference Omer, Behan, Waddington and O’Callaghan2010) was a pioneering event that long preceded the Health Service Executive National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis and subsequently facilitated the establishment of a second EIS, the Cavan–Monaghan Mental Health Service (CMMHS) Carepath for Overcoming Psychosis Early (COPE) in 2012 (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Sardinha, Nwosu, McDonough, De Coteau, Duffy, Waddington and Russell2015). Since then: DETECT has reported prospective findings over its first 7 years of operation (Lyne et al. Reference Lyne, O’Donoghue, Roche, Behan, Jordan, Renwick, Turner, O’Callaghan and Clarke2015); the North Lee Mental Health Service has reported a retrospective, descriptive study of their EIS over a 5-year period (Lalevic et al. Reference Lalevic, Scriven and O’Brien2019); the South Lee Mental Health Service has reported a retrospective case review of a pilot EIS over a 14-month period (Murray & O’Connor, Reference Murray and O’Connor2019). This article first outlines the real-world actualities and vicissitudes of the development and operation of COPE.

Carepath for overcoming psychosis early

Development and operation

As described previously in detail (Waddington & Russell, Reference Waddington and Russell2019), in 1995 philanthropic funding allowed the initiation of two parallel studies of first episode psychosis (FEP): one involving the St. John of God Hospitaller Ministries and Cluain Mhuire Community Mental Health Services (hereafter SJoG); the other involving CMMHS and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland [hereafter the Cavan–Monaghan First Episode Psychosis Study (CAMFEPS)]. Between 1995 and 1999, these two studies operated in parallel, using overlapping staff training and assessment methods. Thereafter, the SJoG study evolved into DETECT (Omer et al. Reference Omer, Behan, Waddington and O’Callaghan2010), while CAMFEPS continued through to 2010, after which it evolved into COPE (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Sardinha, Nwosu, McDonough, De Coteau, Duffy, Waddington and Russell2015).

Fundamental to CAMFEPS was a model based on a registrar/clinical research fellow having both sessional service commitments and a research role via embedding within CMMHS. Thus, he/she was integral to CMMHS, in which primary care liaison and use of home-based treatment as an alternative to hospital admission are central to the delivery of mental health services (McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, Rooney, Clarke, Carey and Owens2003; Russell et al. Reference Russell, McCauley, MacMahon, Casey, McCullagh and Begley2003, Reference Russell, Nkire, Kingston and Waddington2019; Nwachukwu et al. Reference Nwachukwu, Nkire and Russell2014). In 2009, during which CAMFEPS was completing its 15-year tenure, CMMHS took the decision to establish COPE as Ireland’s first rural-based EIS. With advice from DETECT, this led to a prototype EIS model that combined the DETECT experience with the particular setting and requirements of CMMHS, together with their shared commitment to embedded research studies, followed by refinement of an integrated, multidisciplinary EIS model with attendant challenges vis-à-vis availability of resources within an already stretched health service. As part of the development process each General Practitioner (GP) in counties Cavan and Monaghan was invited to participate in a study to evaluate their baseline knowledge of and attitudes to psychotic illness, followed by delivery of an education programme to increase awareness and encourage rapid referral of psychosis (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Sardinha, Nwosu, McDonough, De Coteau, Duffy, Waddington and Russell2015). The last of 432 subjects was incepted into CAMFEPS in April 2010 (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b) under the care of CMMHS. Progressively, through to December 2011, 33 individuals with newly presenting FEP were incepted into the prototype COPE model and, following refinements, in January 2012 the COPE model was launched by CMMHS as its EIS for FEP.

The COPE EIS model (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Sardinha, Nwosu, McDonough, De Coteau, Duffy, Waddington and Russell2015) for persons presenting with FEP at age 16 and above in counties Cavan or Monaghan [total population 133,666 (2011 census)] involved tailored, evidence-based interventions provided through the Community Mental Health Team (CMHT), Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS), and Mental Health Service for the Elderly (MHSE). From bases in Cavan and Monaghan, these included: pharmacological and psychological treatment, including cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis; social skills training and occupational therapy; behavioural family therapy; metabolic profiling; clinical follow-ups to evaluate treatment response and metabolic profile at 3, 6, and 12 months; where necessary, the community rehabilitation service was available. The COPE team included, from within existing resources, a consultant lead for its clinical arm, an academic lead for its research arm, a COPE registrar, a senior clinical psychologist, an occupational therapist, a social worker, and a COPE administrator. This team met regularly to oversee COPE activities. GPs in the catchment areas were the primary source of referrals to CMMHS, which were facilitated by regular on-site liaison visits to their practices as part of the established primary care liaison service (Russell et al. Reference Russell, McCauley, MacMahon, Casey, McCullagh and Begley2003, Reference Russell, Nkire, Kingston and Waddington2019).

Postscript

COPE operated as described above between 2012 and 2016, including sequential appointments of a COPE registrar integral to CMMHS. These embedded appointments, each having tenure for 2 years, were established during CAMFEPS (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Nkire, Kingston and Waddington2019) and continued thereafter to include involvement in the development of COPE and then a fundamental role in its day-to-day activities under the supervision of the clinical and academic leads. In 2016, diminishing resources no longer allowed for such 2-year appointments, which were reduced to a 1-year and subsequently a 6-month tenure in accordance with conventional Non-Consultant Hospital Doctor rotations. The length of induction for each appointee, which required extensive training with his/her predecessor at COPE and colleagues at DETECT before and following their appointment, became problematic given such brevity of tenure and, in efforts to sustain COPE, the number of assessment instruments was substantially reduced. Critically, such attrition in resources extended to the non-replacement and diversion of allied health professionals previously allocated to COPE; these included diminution in psychology services and lack of cover for maternity leave in occupational therapy and social work. Recognising the National Clinical Programme for Early Intervention in Psychosis vis-à-vis the breadth and depth of demands on resources in CMMHS, priorities were directed more broadly to CMHT. In the face of such vicissitudes and associated restructuring, and despite the best endeavours of the COPE team, the clinical lead ultimately felt that this service could not be sustained to the required standard. Thus, COPE was suspended by CMMHS in May 2019 pending the availability of appropriate resources.

Nevertheless, data accumulated during the operation of COPE constitute a rich resource for prospective studies of the impact of EIS on an FEP cohort from initial presentation to long-term outcome. While the assessments to be detailed below were integral to clinical care under the COPE service, the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Service Executive Dublin North East Area gave approval for patient data to be used also for research to advance understanding of psychotic illness and health care provision. This included subjects giving written informed consent to such use of their data after this had been fully explained; informed consent was also sought from a parent or guardian for those aged 16 or 17. Here, initial findings on inceptions into COPE during 2012–2016 are described.

Aims

To: (i) document the development and operation of this rural EIS; and (ii) compare clinical characteristics across diagnoses to address enduring controversies regarding the extent to which boundaries between psychotic diagnoses are arbitrary and porous in the face of continuously distributed dimensions of psychopathology (Guloksuz & van Os, Reference Guloksuz and van Os2018; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b).

Methods

Data collection

The following demographics were recorded for inceptions into COPE: age, sex, marital status, employment status, referral source to CMMHS (via GP or Emergency Department), referral source from CMMHS to COPE (via CMHT, CAMHS or MHSE), and COPE intervention (required or not required). Each COPE registrar gained competency in use of the assessment instruments via training delivered by both their predecessors and the generosity of colleagues in DETECT. Training of each COPE registrar took place before and during the early course of replacing their predecessor in assessment of FEP cases. Following referral for initial clinical evaluation and intervention, subjects incepted into COPE entered formal assessments as soon as was practicable using first the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002); at 6 months thereafter, all clinical information, to include case notes and discussions with treating teams, were reviewed to confirm or update the initial DSM-IV diagnosis as more stable and representative (Baldwin et al. Reference Baldwin, Browne, Scully, Quinn, Morgan, Kinsella, Owens, Russell and Waddington2005; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b). Then, the instruments indicated below were applied.

Psychopathology was assessed using: (i) the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al. Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987) for continuity with CAMFEPS, as total score (PANSS-t) and subscale scores for positive (PANSS-p), negative (PANSS-n) and general (PANSS-g) symptoms; and (ii) for greater incisiveness the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1984), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1983), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; Young et al. Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer1978), and Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS; Addington et al. Reference Addington, Addington and Schissel1990).

Cognition was first assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al. Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) for general cognition and the Executive Interview (EXIT; Royall et al. Reference Royall, Mahurin and Gray1992) for executive/frontal lobe function (Baldwin et al. Reference Baldwin, Browne, Scully, Quinn, Morgan, Kinsella, Owens, Russell and Waddington2005; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b).

Extrapyramidal movement disorder was assessed using the Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS; Simpson & Angus, Reference Simpson and Angus1970). Involuntary movements were assessed using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS; Guy, Reference Guy1976).

Premorbid intellectual functioning was assessed using the National Adult Reading Test (NART; Nelson, Reference Nelson1982). Premorbid adjustment was assessed using the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS; Cannon-Spoor et al. Reference Cannon-Spoor, Potkin and Wyatt1982).

Insight was assessed using the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD; Amador et al. Reference Amador, Strauss, Yale, Flaum, Endicott and Gorman1993) and the Birchwood Insight Scale (BIS; Birchwood et al. Reference Birchwood, Smith, Drury, Healy, Macmillan and Slade1994).

Quality of life was assessed using the Quality of Life Scale (QLS; Heinrichs et al. Reference Heinrichs, Hanlon and Carpenter1984). Functioning was evaluated using the MIRECC version of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (MGAF; Niv et al. Reference Niv, Cohen, Sullivan and Young2007), with subscale scores for occupational (MGAF1), social (MGAF2), and symptomatic (MGAF3) functioning.

Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and duration of untreated illness (DUI) were assessed using the scale of Beiser and colleagues (Beiser et al. Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono1993): DUP was defined as the period between first noticeable psychotic symptoms and receipt of antipsychotic treatment; DUI was defined as the period between first noticeable behavioural abnormality and receipt of antipsychotic treatment (Beiser et al. Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono1993; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a). Information used in completing this scale was derived from interview with the patient regarding illness and psychosis onset, review of all medical records, interview with initial clinicians where possible, and interview with family and friends where available and able to give information regarding illness and psychosis onset.

Statistical analysis

This followed previously described procedures (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a, Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b). Rate of inception into COPE is expressed as the annual number of cases per 100,000 of population aged ≥15 years (2011 census), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for rates and rate ratios (RR). These analyses were performed using Stata Release 14. Demographic and assessment data are expressed as means with standard deviations (s.d.) and, for age, DUP and DUI, also as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). For diagnoses having five or more cases, data for each demographic and clinical variable were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test that compared each diagnosis to schizophrenia as reference. Because of their substantially right-skewed distributions (see Results), DUP and DUI were analysed following the transformations log10[1 + DUP] (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla2001; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a) and log10[1 + DUI], respectively, hereafter referred to as logDUP and logDUI. Significance was indicated by p < 0.05. For diagnoses having less than five cases, formal statistical analysis was precluded and data are presented descriptively.

Results

Operation of COPE

Over the 4.5-year period between January 2012 and June 2016, 115 individuals with FEP [78 male (67.8%), 37 female (32.2%)] were incepted into COPE. The majority of cases were referred initially to CMMHS via their GP [81 (70.4%)] and a minority via the Emergency Department [34 (29.6%)], with females [16 of 37 (43.2%)] more likely to be referred by the Emergency Department than males [18 of 78 (23.1%); p < 0.05]. From CMMHS, the majority of inceptions were referred to COPE via CMHT [111 (96.5%)] and minorities via CAMHS [2 (1.7%)] and MHSE [2 (1.7%)]. Patterns of inception did not differ between the sexes. Of the 115 inceptions, 104 [71 of 78 males (91.0%), 33 of 37 females (89.2%)] were subsequently deemed to require COPE intervention and 11 [7 males (9.0%), 4 females (10.8%)] were subsequently deemed not to require COPE intervention; the reasons for incepted cases not requiring COPE intervention were brief psychotic disorder, which by definition involves a transient FEP that rapidly resolves, and instances of psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition where that medical condition could be readily addressed.

A small number of FEP cases presenting to CMMHS and referred to COPE were not incepted for reasons that included: history of previous presentation(s) with a psychotic episode; occasional decisions to optimise care by retaining individual FEP cases within CAMHS and particularly MHSE; absence of clinical evidence of psychosis, a small number of whom were considered to show signs of the prodrome of psychotic illness (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016) [sometimes referred to as attenuated psychosis syndrome (Salazar de Pablo et al. Reference Salazar de Pablo, Catalan and Fusar-Poli2020) or clinical high risk for psychosis (Fusar-Poli, Reference Fusar-Poli2017)]. COPE was not conceived or structured to intervene in such instances, which were managed within CMMHS. Operational reasons for non-inception included: deceased or relocated from the catchment area between FEP and inception; CMMHS policy that two successive non-attendances at appointments results in discharge from its services.

Among the 115 cases incepted into COPE, following first psychotic presentation to a GP or to the Emergency Department median time to referral to CMMHS was 0 days [mean 0.4 (s.d. 2.6), range 0–27 days]. Following referral to CMMHS for initial evaluation and care, median time to referral to COPE was 7 days [mean 11.4 (s.d. 13.3), range 0–72 days]. Following inception into COPE for initiation of the EIS programme, median time to commencing formal assessments was 12 days [mean 16.6 days (s.d. 14.5), range 0–68 days]. As elaborated further below, following first psychotic presentation median time to initiation of antipsychotic treatment was 0 days [mean 0.4 (s.d. 2.9), range 0–27 days].

The majority of inceptions into COPE had never married [66 (57.4%)] or were married/in a long-term relationship [36 (31.3%)], widowed [3 (2.6%)], divorced [5 (4.3%)] or separated [5 (4.3%)]. The majority of referrals were unemployed [69 (60.0%)]; for one (0.9%) employment status could not be established. Social demography did not differ between the sexes.

Demographics

The 115 inceptions into COPE received DSM-IV diagnoses at 6 months as follows: schizophrenia (SZ), n = 39; schizophreniform disorder (SF), n = 3; brief psychotic disorder (BrP), n = 7; schizoaffective disorder (SA), n = 2; bipolar I disorder (BD), n = 13; major depressive disorder with psychotic features (MDDP), n = 26; delusional disorder (DD), n = 3; substance-induced psychotic disorder (SIP), n = 15; psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition (PGMC), n = 5 (one arteriovenous malformation, one hyperthyroidism, one hypothyroidism, two temporal lobe epilepsy); psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (PNOS), n = 2. No cases of substance-induced mood disorder with manic features, or mood disorder due to a general medical condition, with manic features, were encountered.

Table 1 shows mean and median ages at inception into COPE by sex across all diagnoses and for each diagnostic category at 6 months. Median age was lower than the mean for most diagnoses, due to the majority referred at younger ages, except for BrP or PNOS. There were no differences in age at inception between the sexes.

Table 1. Number of cases incepted into COPE and age at first presentation by diagnostic category at 6 months

SZ, schizophrenia; SF, schizophreniform disorder; BrP, brief psychotic disorder; SA, schizoaffective disorder; BD, bipolar I disorder; MDDP, major depressive disorder with psychotic features; DD, delusional disorder; SIP, substance-induced psychotic disorder; PGMC, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition; PNOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Data are number of cases, mean age (s.d.), median {interquartile range}, [range].

Table 2 shows the rate of inception into COPE by sex across all diagnoses and for each diagnostic category at 6 months. Annual rate was 24.8/100,000 of population aged ≥15 years. Rate for inception into COPE was higher among males than females for the following diagnostic categories: 2.1-fold higher (p < 0.001) across all psychoses; 3.3-fold higher (p < 0.001) for SZ; 13.9-fold higher (p < 0.001) for SIP.

Table 2. Annual rate of inception into COPE by diagnostic category at 6 months

SZ, schizophrenia; SF, schizophreniform disorder; BrP, brief psychotic disorder; SA, schizoaffective disorder; BD, bipolar I disorder; MDDP, major depressive disorder with psychotic features; DD, delusional disorder; SIP, substance-induced psychotic disorder; PGMC, psychotic disorder due to general medical condition; PNOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Data are annual rate/100,000 of population aged ≥15 (95% confidence interval) with number of cases.

RR, relative risk in males v. females (95% confidence interval).

*** p < 0.001, risk greater in males than in females.

Clinical assessments

Assessments of psychopathology are shown in Table 3. PANSS-t, PANSS-p, and PANSS-g scores did not differ from SZ for any other diagnostic category. PANSS-n score was lower (p < 0.02) in BD than in SZ, but did not differ from SZ for any other diagnostic category. SAPS score did not differ from SZ for any diagnostic category. SANS score was lower in BD (p < 0.001), MDDP (p < 0.05), SIP (p < 0.05), and PGMC (p < 0.01) than in SZ, but did not differ from SZ for any other diagnostic category. YMRS score was higher (p < 0.02) in BD than in SZ, but did not differ from SZ for any other diagnostic category. CDSS score did not differ from SZ for any diagnostic category. There were no differences between the sexes and all scores were unrelated to age.

Table 3. PANSS, SAPS, SANS, YMRS, and CDSS psychopathology scores by diagnostic category at 6 months

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale: PANSS-t, total symptoms; PANSS-p, positive symptom subscale; PANSS-n, negative symptom subscale; PANSS-g, general symptom subscale; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; SZ, schizophrenia; SF, schizophreniform disorder; BrP, brief psychotic disorder; SA, schizoaffective disorder; BD, bipolar I disorder; MDDP, major depressive disorder with psychotic features; DD, delusional disorder; SIP, substance-induced psychotic disorder; PGMC, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition; PNOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Data are mean scores (s.d.), number of cases.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.02.

*** p < 0.001 v. SZ as reference.

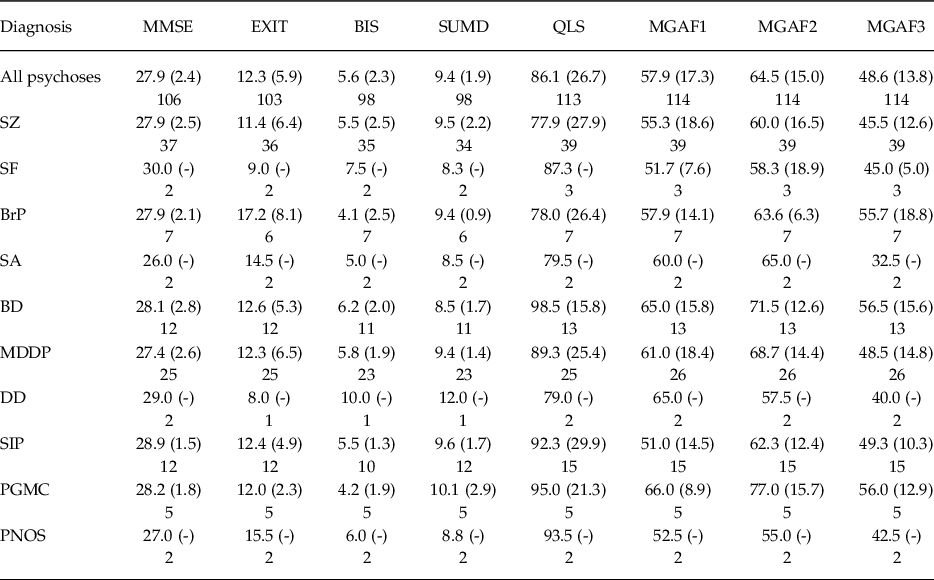

Assessments of neuropsychology are shown in Table 4. Neither MMSE nor EXIT scores differed from SZ for any diagnostic category. There were no differences between the sexes. MMSE score decreased with age (p < 0.02), while EXIT score was unrelated to age. Across all diagnoses at 6 months, mean SAS score [0.4 (s.d. 0.9), n = 102] and AIMS score [0.1 (s.d. 0.5), n = 103] were so low as to preclude statistical analysis (data not shown).

Table 4. MMSE, EXIT, BIS, SUMD, QLS, MGAF1, MGAF2, and MGAF3 scores by diagnostic category at 6 months

MMSE, mini-mental state examination; EXIT, executive interview; BIS, birchwood insight scale; SUMD, scale to assess unawareness of mental disorder; QLS, quality of life scale; MGAF1, MIRECC global assessment of functioning scale – occupational functioning; MGAF2, MIRECC global assessment of functioning scale – social functioning; MGAF3, MIRECC global assessment of functioning scale – symptomatic functioning; SZ, schizophrenia; SF, schizophreniform disorder; BrP, brief psychotic disorder; SA, schizoaffective disorder; BD, bipolar I disorder; MDDP, major depressive disorder with psychotic features; DD, delusional disorder; SIP, substance-induced psychotic disorder; PGMC, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition; PNOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Data are mean scores (s.d.), number of cases.

Assessments of insight are shown in Table 4. Neither Birchwood Insight Scale nor SUMD scores differed from SZ for any diagnostic category. While there was no difference in BIS score between the sexes, SUMD scores were lower in females than in males (p < 0.05); both scores were unrelated to age.

Assessments of quality of life and functioning are shown in Table 4. Neither QLS nor MGAF1/2/3 scores differed from SZ for any diagnostic category. There were no differences in QLS or MGAF1/2/3 scores between the sexes and both scores were unrelated to age.

Assessments of premorbid features and DUP/DUI are shown in Table 5. Neither NART nor PAS scores differed from SZ for any diagnostic category. There were no differences in scores between the sexes and both scores were unrelated to age. Median DUP and DUI were shorter than their respective means by many months across all diagnoses and for SZ, BrP, MDDP, SIP, and PGMC, due to the majority of cases having relatively short durations and a minority having considerably longer durations that indicated substantially right-skewed distributions. DUI was substantially longer than DUP in terms of both mean and median across all diagnoses and for SZ, BrP, MDDP, SIP, and PGMC. In contrast, for BD both durations were brief and considerably shorter than for SZ (DUP, p = 0.05; DUI, p = 0.02). There were no differences between the sexes and both measures were unrelated to age.

Table 5. DUP and DUI with PAS and NART scores by diagnostic category at 6 months

SZ, schizophrenia; SF, schizophreniform disorder; BrP, brief psychotic disorder; SA, schizoaffective disorder; BD, bipolar I disorder; MDDP, major depressive disorder with psychotic features; DD, delusional disorder; SIP, substance-induced psychotic disorder; PGMC, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition; PNOS, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified.

Data for DUP and DUI are mean (s.d.), median {interquartile range}, [range] in months and number of cases.

Data for NART and PAS scores are means (s.d.) and number of cases.

* p = 0.05.

** p = 0.02 v. schizophrenia as reference, analysed using logDUP and logDUI.

Initiation of antipsychotic treatment

Among the 115 referrals, 109 (94.8%) received initial treatment with an antipsychotic on the day of first presentation with psychosis; for five cases antipsychotic treatment was initiated at 1–27 days after first presentation (for three cases of MDDP after 1, 4, and 5 days; for one case of ‘disorganised’ SZ after 14 days; for one case of SIP after 27 days); for one case of PGMC no antipsychotic was prescribed and the antiepileptic drug valproate was initiated on the day of first presentation for psychosis associated with epilepsy. For the 114 referrals receiving antipsychotic treatment, this was initiated for 111 (97.4%) with a second-generation agent (aripiprazole, n = 4; olanzapine, n = 78; quetiapine, n = 9; risperidone, n = 20) and for 3 (2.6%) with a first-generation agent [each haloperidol]; other non-antipsychotic drugs were prescribed according to clinical need.

Discussion

This report documents the origins, development, initiation, and operation of COPE and presents prospective research findings during its first 5 years of operation, that is, for inceptions over 4.5 years in relation to diagnoses at 6 months post-inception.

Operational aspects

Critically for an EIS (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016), median delay from first psychotic presentation, whether via their GP or the Emergency Department, to initiation of antipsychotic treatment was 0 days, with this being longer than 0 for only five of 114 cases (4.4%) whose presentations were among the more complex and included the turmoil of affective and drug-induced psychotic symptoms. These rapid referrals to CMMHS and on to COPE, most commonly initiated via GPs and resulting in timely access to care with swift initiation of antipsychotic treatment, attest the value placed in CMMHS on close working relationships with primary care (Russell et al. Reference Russell, McCauley, MacMahon, Casey, McCullagh and Begley2003).

While instances of FEP aged less than 16 were not incepted into COPE, such cases are extremely rare (Driver et al. Reference Driver, Thomas, Gogtay and Rapoport2020) and only two cases aged 16 or 17 were referred to COPE via CAMHS. However, an unexpected aspect of COPE, despite no arbitrary upper age cut-off, was referral of only three cases aged over 65, two via MHSE and one via CMHT. Late onset psychosis is increasingly recognised when arbitrary upper age cut-offs are not applied (Van Assche et al. Reference Van Assche, Morrens, Luyten, Van de Ven and Vandenbulcke2017; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Howard and Kirkbride2018; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b). Furthermore, such instances typically involve an over-representation of MDDP relative to SZ and other FEP diagnoses (Jaaskelainen et al. Reference Jääskeläinen, Juola, Korpela, Lehtiniemi, Nietola, Korkeila and Miettunen2018; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Howard and Kirkbride2018; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b; Waddington et al. Reference Waddington, Kingston, Nkire, Russell, Tamminga, Ivleva, Reininghaus and van Os2021). That few older cases of MDDP were incepted into COPE may be influenced by occasional clinical decisions that MHSE was best placed to provide optimal care for some instances of FEP in older persons. Individuals presenting with late-onset FEP constitute an under-appreciated group where EIS has received little investigation and its effectiveness remains to be clarified (Lappin et al. Reference Lappin, Heslin, Jones, Doody, Reininghaus, Demjaha, Croudace, Jamieson-Craig, Donoghue, Lomas, Fearon, Murray, Dazzan and Morgan2016; O’Driscoll et al. Reference O’Driscoll, Free, Attard, Carter, Mason and Shaikh2021).

Though the social demography of persons incepted into the three previously reported EIS in Ireland (Lyne et al. Reference Lyne, O’Donoghue, Roche, Behan, Jordan, Renwick, Turner, O’Callaghan and Clarke2015; Lalevic et al. Reference Lalevic, Scriven and O’Brien2019; Murray & O’Connor, Reference Murray and O’Connor2019) are generally similar to those described here for COPE, it is difficult to make systematic comparisons due to differences in urban versus rural setting, EIS model adopted, structure of the mental health services within which each EIS is embedded, prospective versus retrospective collection of data, presence versus absence of an integrated research component, and scope of reporting operational aspects vis-à-vis clinical evaluations. Though diverse, at this early stage in the journey to EIS in Ireland (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016; Power, Reference Power2019) each has value within its own frame-of-reference and adds to the knowledge base that may assist other mental health services as they move to implement EIS.

Research findings

As expected in the absence of any arbitrary diagnostic restriction or upper age cut-off, the epidemiology of inceptions into COPE was generally similar to that of FEP in CAMFEPS (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b): diagnostic diversity and overall male preponderance that was more marked for SZ and particularly SIP and less evident for non-schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses; yet the most populous functional FEP diagnoses (SZ, BD, and MDDP) were each evident in both sexes from the late teens through to the tenth decade. The one epidemiological finding evident in CAMFEPS but not in COPE was older age at FEP among females and MDDP. This may reflect the relatively few cases of late-onset psychosis referred to COPE, which typically contain an enrichment of females and MDDP (van der Werf et al. Reference Van der Werf, Hanssen, Kohler, Verkaaik, Verhey, Investigators, van Winkel, van Os and Allardyce2014; Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Howard and Kirkbride2018; Waddington et al. Reference Waddington, Kingston, Nkire, Russell, Tamminga, Ivleva, Reininghaus and van Os2021).

Positive and general PANSS symptoms for inceptions into COPE did not differ between diagnoses; PANSS negative symptoms were lower in BD than in SZ, as noted in CAMFEPS (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b). COPE utilised also the SAPS, SANS, YMRS, and CDSS that confirmed an indistinguishable level of positive symptoms across the diagnoses and extended the lower level of negative symptoms in BD also to MDDP, SIP, and PGMC. Furthermore, BD was the only diagnosis showing a higher level of manic symptoms, suggesting phenomenological incompatibility between negative symptoms and elation/grandiosity during an acute manic episode. While MDDP also evidenced a lower level of negative symptoms using the SANS, the level of depressive symptoms using the CDSS was similar across diagnoses, suggesting that assessment of negative symptoms in MDDP was not materially confounded with depressive symptoms. Both SIP and PGMC also evidenced not only levels of positive symptoms indistinguishable from SZ, BD, and MDDP but also a lower level of negative symptoms as evident in BD and MDDP. This suggests that underlying causal factors for positive symptoms in SIP and PGMC may involve mechanisms that overlap with those underlying positive symptoms across the functional psychoses, while mechanisms underlying negative symptoms operate to a greater extent in SZ.

For BrP, levels of initial psychopathology at FEP were similar to those for other functional psychotic diagnoses and for SIP and PGMC but declined rapidly thereafter. In CAMFEPS, while BrP at FEP was characterised similarly by rapid remission, at 6-year follow-up the majority now received a functional psychotic diagnosis of SZ, SA, DD, BD or MDDP (Kingston et al. Reference Kingston, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kinsella, Russell, O’Callaghan and Waddington2013). We note in COPE that among nine cases of BrP at FEP, at 6 months two received a functional psychotic diagnosis: one SZ and one BD. While long-term follow-up of the COPE cohort will further clarify these issues, findings to date reinforce concern that BrP may not be a benign occurrence. For some, it appears to be an early, transient harbinger of long-term evolution to functional psychotic illness that may benefit from continuing review.

Neuropsychology, insight, quality of life, and functionality at FEP did not differ between the functional psychotic diagnoses, SIP and PGMC; these findings are similar to those for MMSE, EXIT, SUMD, and QLS in CAMFEPS. MMSE scores indicated the absence of general cognitive impairment and EXIT scores indicated a modest level of impairment in executive/frontal lobe dysfunction. MGAF1, 2, and 3 scores were each in the borderline-dysfunctional range. In terms of premorbid indices, neither NART nor PAS scores differed between the functional psychotic diagnoses, SIP and PGMC; these findings are also similar to those for CAMFEPS. Both SAS and AIMS scores were so low as to preclude analysis. This would be consistent with assessments made early in the course of minimal exposure to antipsychotic drugs, the overwhelming majority of which were second-generation agents.

Assessment of DUP was extended to the under-investigated and potentially more insidious variable of DUI (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla2001; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a); for DUI, the added interval preceding DUP includes often more prolonged periods of functional deficits, psychological anomalies and sub-threshold psychotic ideation that overlap with what is variously referred to as the psychosis prodrome, the clinical high-risk state for psychosis and attenuated psychosis syndrome (Waddington et al. Reference Waddington, Hennessy, O’Tuathaigh, Owoeye, Russell, Brown and Patterson2012; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a). Both DUP and DUI were characterised by marked right-shift distributions with medians considerably shorter that means, due to the majority of shorter values but a minority of longer and sometimes very long values, as noted previously (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla2001; Penttila et al. Reference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen2014; Register-Brown & Hong, Reference Register-Brown and Hong2014; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016; Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 a).

Values for DUP and DUI were longest for SZ, intermediate for MDDP and SIP, and shortest for BD, reflecting the typically more acute onset of a first manic episode. These DUP values for undifferentiated FEP and for SZ are within but towards the lower end of the range typically reported in FEP populations (Norman & Malla, Reference Norman and Malla2001; Penttila et al. Reference Penttila, Jaaskelainen, Hirvonen, Isohanni and Miettunen2014; Register-Brown & Hong, Reference Register-Brown and Hong2014; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, McDonough, Doyle and Waddington2016) and are not dissimilar to values reported by DETECT (Lyne et al. Reference Lyne, O’Donoghue, Roche, Behan, Jordan, Renwick, Turner, O’Callaghan and Clarke2015) and by the North Lee Mental Health Service EIS (Lalevic et al. Reference Lalevic, Scriven and O’Brien2019) and South Lee Mental Health Service EIS (Murray & O’Connor, Reference Murray and O’Connor2019).

DUP and DUI in PGMC have received little previous investigation; despite the rarity and heterogeneity of PGMC, values were generally comparable with functional psychotic illness, suggesting the emergence of psychosis on a background of psychological features that may evolve in contiguity with the underlying medical condition.

These assessments inform systematically on the comparative durations of DUP and DUI for individual functional psychotic diagnoses, SIP and PGMC. They are important for evaluating in future studies: (a) any impact of COPE on DUP and DUI, requiring as reference a matched CAMFEPS dataset; (b) associations in COPE between DUP/DUI and clinical state at FEP; and (c) those same associations at long-term follow-up of the COPE cohort.

Limitations

Individuals experiencing FEP under age 16 were not included and inceptions of late-onset FEP were fewer than expected, limiting the generalizability of findings. For a very small percentage of FEP experiencing complex presentations (<5%), otherwise rapid initiation of antipsychotic treatment was delayed for some days. The clinical imperative to initiate antipsychotic treatment at the earliest possible stage meant that some influence of that treatment on assessments, however small, could not be excluded.

Conclusions

These vicissitudes in the development, operation, and suspension of COPE may be helpful to other mental health services in Ireland as they develop and initiate their own EIS. Findings to date are heuristic in systematically resolving, across the full diagnostic diversity of EIS, that variations in epidemiology and clinical features are quantitative rather than qualitative, with few points of rarity between psychotic diagnoses. Importantly, by using more incisive instruments these findings elaborate and extend those apparent in CAMFEPS (Nkire et al. Reference Nkire, Scully, Browne, Baldwin, Kingston, Owoeye, Kinsella, O’Callaghan, Russell and Waddington2021 b). More specifically, each of SZ, BD, MDDP, SIP, and PGMC show indistinguishable levels of positive psychotic symptoms and multiple other domains of premorbid functioning and of current impairment and dysfunction, with only negative symptoms in SZ and mania in BD showing quantitative variations.

These findings further elaborate clinical, genetic, and neuroimaging findings that SZ, BD, and MDDP have arbitrary and porous diagnostic boundaries that reflect two realities: first, genetic and environmental factors that interact in a common, transdiagnostic milieu (Brainstorm Consortium, 2018; Castillejos et al. Reference Castillejos, Martin-Perez and Moreno-Kustner2018; Guloksuz & van Os, Reference Guloksuz and van Os2018; Jongsma et al. Reference Jongsma, Gayer-Anderson, Lasalvia, Quattrone, Mulè and Szöke2018; Waddington & Russell, Reference Waddington and Russell2019); second, dysfunction in one or more components of a common neuronal network that has been implicated in the transdiagnostic pathobiology of SZ, BD, and MDDP (Goodkind et al. Reference Goodkind, Eickhoff, Oathes, Jiang, Chang, Jones-Hagata, Ortega, Zaiko, Roach, Korgaonkar, Grieve, Galatzer-Levy, Fox and Etkin2015; Sheffield et al. Reference Sheffield, Kandala, Tamminga, Pearlson, Keshavan, Sweeney, Clementz, Lerman-Sinkoff, Hill and Barch2017; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Dillon, Patrick, Roffman, Brady, Pizzagalli, Ongur and Holmes2018; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Tang, Wang, Liao, Jiang, Wei, Mechelli, He and Xia2019; Tu et al. Reference Tu, Bai, Li, Chen, Lin, Chang and Su2019; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Luo, Palaniyappan, Yang, Hung, Chou, Lo, Liu, Tsai, Barch, Feng, Lin and Robbins2020) and extends to both PGMC (Joyce, Reference Joyce2018; Waddington, Reference Waddington2020) and SIP (Khokhar et al. Reference Khokhar, Dwiel, Henricks, Doucette and Green2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Cavan–Monaghan Mental Health Service and Drs Savio Sardinha and Pranith Perera for all their contributions to COPE, Professor Ronan Conroy, RCSI Data Science Centre, for assisting in analysis of incidence data and Professor Mary Clarke and her colleagues at DETECT for their kind assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All protocols relating to COPE were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Service Executive Dublin North East Area. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Financial support

COPE was not supported by any external funding and was integral to Cavan–Monaghan Mental Health Service.