INTRODUCTION

This article examines the handloom sector in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh (the modern-day northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh) in the twentieth century to explore how colonial knowledge discourse about indigenous forms of production and knowledge created an artificial dichotomy between a dynamic “modernity” and an ossified “tradition”. However, this dichotomy did not actually exist. Despite their apparent “backwardness”, weavers adopted and adapted “modern” technologies while preserving existing community networks and hierarchies. This article explores how global colonialism on the one hand, and the reforging of existing knowledge systems on the other, transformed the local handloom industry, its work culture, and labour organization. By the early nineteenth century, we see a transition from a handicrafts economy, rooted in a gendered division of labour within the household, to a modern political economy in which productive work was defined as taking place outside the household and on the shop floor in factories. Consequently, dense and sophisticated worlds of labour skills, around which whole artisanal economies were organized, were designated as “backward”. This labelling of traditional handicrafts as “backward” can be traced to the Industrial Revolution, when European intellectuals began to think of “the economy” as a distinct realm, separate from the household and populated by male income earners. A new discourse emerged, which emphasized a chronological progress towards “stronger”, “modern” production systems. In this new philosophy, factories and industries were seen as a means to achieve socio-economic developmental goals through the deployment of technology. When this new capitalist model was applied in European colonies, here, just as in Europe, domestic work performed by weavers largely became invisible. However, the sector did not vanish entirely. Small-scale producers in artisan communities continued to work within their household and using domestic labour. They sourced inputs and marketed their products through community networks, evolving with changing consumer demands.

Therefore, the ideological erasure of handloom work should not be confused with its actual disappearance. Rather, it was precisely because such work was construed as backward and unimportant that it could escape systemic institutional transformation. I contend that our understanding of modern social life and its knowledge systems need to include local community-based work practices. The histories of modern sciences and local skills do not simply produce polarized views of community-based professions versus industrialized work but show how they borrowed and learned from each other in the making and using of objects. As Sudipta Kaviraj reminds us, modernity is not a single, homogeneous process, but an uneven and sequential combination of several interconnected processes of social change. First experienced in the Western European context, modernity is a historically contingent combination of various constituent elements that produced different histories of the modern under different geographic and socio-economic circumstances. Making a case for an alternate theory of experiences of modernity in non-European societies, Kaviraj seeks to accommodate the historical reality of multiple or differential modernities. Even if experiences of modernity were uniform, what existed before it must have been structurally diverse, and these structures constituted the “initial” or prior conditions from which modern institutions began to arise.Footnote 1 For Kaviraj, late-colonial and postcolonial attempts to instantiate modernity are plural and diverse, but all are based on a normative model of modernity founded upon nineteenth-century European experience, making this a point of reference for the efforts made by colonial reformers, modernizing nationalists, and postcolonial elites to transform colonized societies emerging into independence. Yet, the actual pattern necessarily diverges from this normative background, because of the recursive effects of political processes and the expansion of a “popular” domain of politics, which increasingly makes demands upon the state that are incompatible with the “model”, creating major tensions for modernizing projects. Partha Chatterjee had already flagged that it is problematic at best to establish cross-cultural commonalities to question the affiliated notions of “alternative modernity”.Footnote 2

This article does not claim to follow the above framework in its entirety; yet, how the double nature of this modernity – that it is substantially modelled upon a certain normative “Western” modernization and, at the same time, is constantly marking its own difference and divergence from it – is important, for instance, when considering nationalist ideas about how to remodel and modernize the economy, and therefore for this study of the handloom weavers. This understanding gives us a more nuanced theoretical lens to study the handloom sector beyond the dichotomy of tradition and modernity.

A case study of the city of Calcutta by Swati Chattopadhyay explains such fault lines in the modernity introduced in overseas colonies as being the result of contestations, mediations, and adaptations by the inhabitants of each colony. The intentional, reflective, and strategic use of certain practices and forms of modernity led to a “translation” or adaptation of the Western ideals of individuality, progress, and division of public and private life to make them suitable to the Indian setting, resulting in a “polarized” modernity. Simultaneously, anxieties rooted in notions of interracial mixing, hybridity, and corruption of identity through exposure to foreign practices led to a nationalist call to return to indigenous artisanal products. However, this cannot be simplified as one-way process. The opposite was also the case as some colonial subjects embraced modernity for their own agendas. For example, English-educated Bengali intellectuals came up with their own translations of modernity and became tools of “cultural and political intervention”,Footnote 3 with the potential to challenge models of Western modernity. According to Chattopadhyay, the Bengali nationalism deployed in this context was as always an urban male discourse. The writings of intellectual leaders of that time reveal the maleness of nationalist thought and representations and the ways in which women in the public space (such as prostitutes or actresses) were invisibilized.Footnote 4 This process of invisibility was key to the new forms of hierarchy that emerged. This argument, when extended to the handloom weavers’ invisibility in the public sphere of north India, provides a theoretical lens to understand how colonial rhetoric and policies prompted different local responses and yielded varied experiences and results.

Fusing external technologies and tools with hereditary skills was a long-drawn process that saw numerous conflicts between the approaches of colonial policymakers, the bureaucracy, and indigenous subjects – i.e. nationalist intellectuals – on the one hand, and weavers on the other. The implementation of new methods on the ground and efforts of weavers and nationalist intellectuals to circumvent them in the context of the colonial state and economy are worth exploration. This article argues that handloom work was simultaneously transformed and obscured as intangible production skills were only partially colonised. Hence, I trace the historical roots and local contexts of places of production, materials, skills, and product designs before assessing the craftsperson's response to modernity. The idea is not merely to comprehend how handloom weavers adapted the new knowledge, technologies, and products of modernity to their craft, but, more importantly, how far new technologies were integrated with extant cultural notions of work and the everyday life experiences of weaver communities. The technology travelled through the diffusion of consumer habits and subsequent adaptation of the weavers. Weavers adapted European yarns, designs, colour codes, and textiles to local techniques and tastes, or vice versa. However, this appropriation did not change the local work culture. In this profession, reeling, bleaching, dyeing, and warping of the yarn; winding the thread onto bobbins for use as weft yarn; and embroidering saris and sizing them was a mainstay for the social life of work. Thus, the production of cloth as part of the community life cycle remained dependent on networks of cooperation between weavers who helped each other in these tasks.

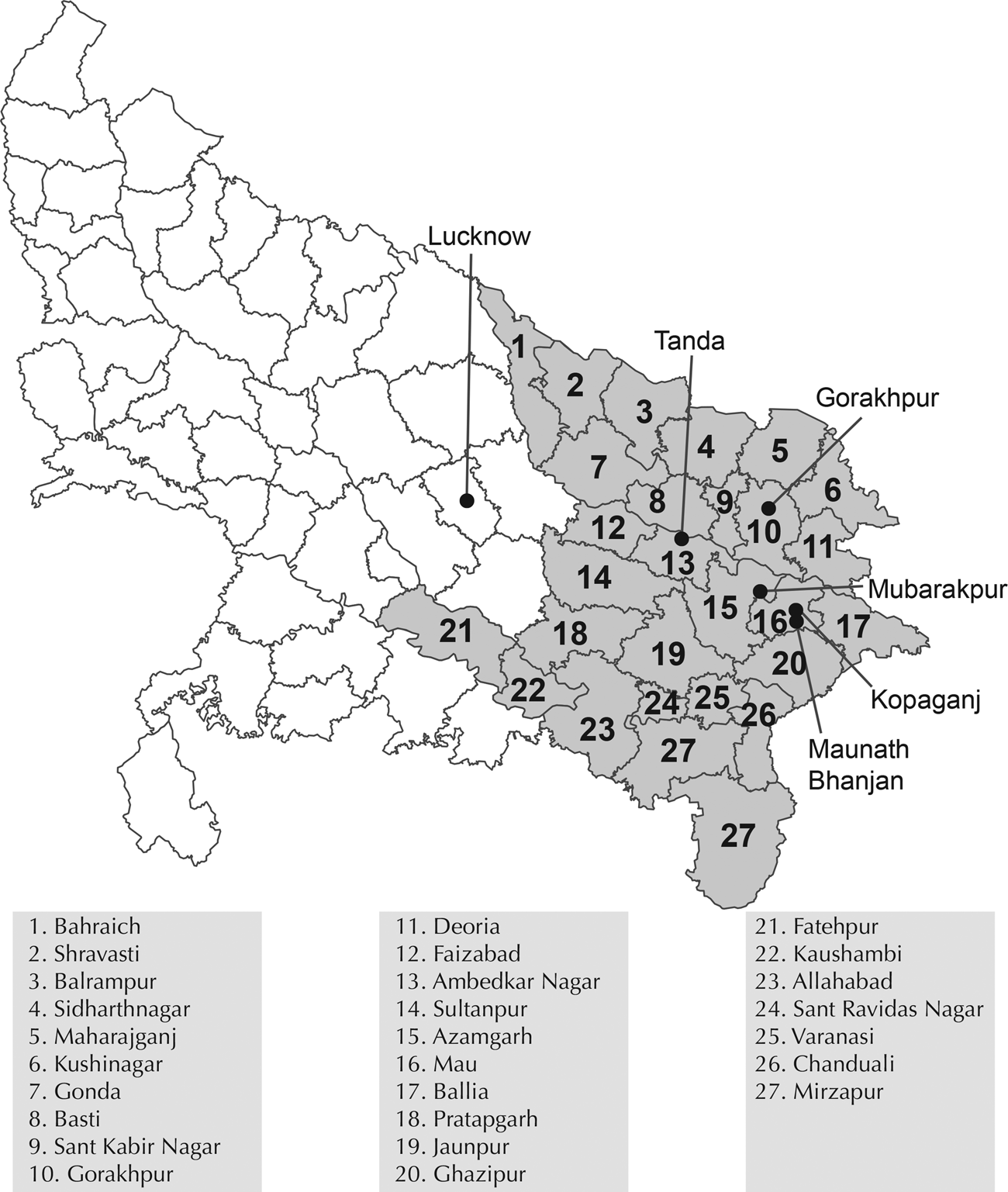

This paper focuses on the handloom industry in the United Provinces (Figure 1) during the early twentieth century. The handloom textile manufactures of this region specialized in cotton, silk, and wool fabrics. Here, we focus on cotton and silk, as they reflect procedural shifts the clearest, and both were being used together to produce mixed types of cloths. Though handloom weaving as a profession was connected to various caste identities in this region, I have focused on the most dominant caste group, the Muslim Julaha weavers, who represented almost ninety per cent of the handloom labour force during the early twentieth century.

Figure 1. Weaving centres of the eastern United Provinces.

This article has been divided into four sections. The first section investigates existing historiographical concerns and possibilities in terms of the skill–knowledge discourse in global histories of the craft sector. The second section deals with the multiple ways in which weaving spaces in this region survived shifts in textiles, production, and consumer preferences. The third section examines how the European experience of a knowledge economy led to the development of a formal skills training programme in this region and established a rudimentary structure for industrial and technical education. Here, the consolidation of colonial pedagogy, through the diffusion of modern knowledge of handloom technologies and the nationalist drive to redefine crafts in line with its larger agenda, has been examined in detail. The fourth section discusses the interface of the global colonial economy with the work culture of weavers, leading to innovations, adaptations, and failures, as well as to moments of resistance driven by the politicization of workers’ concerns. While acknowledging the manifold hierarchies within the category of “weavers”, this article largely focuses on the relationship between the state and weavers.

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ISSUES AND POSSIBILITIES

The skills of Indian handloom production are embedded in community practices, institutions, relationships, and rituals. Attempts to reclaim and represent the North Indian handloom industry's indigenous ways of knowing, underscore its status and place in global knowledge production, and challenge past and present prejudices have been few and far between. Colonial enlightenment and indigenous elites established a hierarchy that privileged “the manufacturing sciences” and devalued other practices. Consequently, all non-Western methods of textile production were relegated to the status of “unscientific”. This article aims to challenge the privileging of colonial and Western forms of knowledge by investigating indigenous skilled knowledge. It shows how, till recently, the binary created by colonial knowledge production continued to affect modern economic history as well, before the latest perspectives started seeing colonialism and indigenous communities as connected, mutually constitutive, and in a dialogue with each other, to arrive at new ways of connecting the history of the Global South to that of the Global North.

Here, my context is the recent trend in historiography of studying skilled craft communities using the theoretical models of “useful knowledge” and the “knowledge economy”.Footnote 5 From Michael Polanyi onwards, extensive theoretical and empirical research on the knowledge economy has focused on local skills, craft, and talent as the vital components of “tacit knowledge”.Footnote 6 Such paradigms have remained Eurocentric – for example, Joel Mokyr and some other scholars worked with notions of tacit and codified knowledge to develop the concept of “useful knowledge”, which, for them, was the primary contributor in Western industrialization that led to the “Great Divergence”.Footnote 7 This “useful knowledge” was seen as fundamentally European, as historians such as Stephan R. Epstein trace its roots to “local knowledge”, the special “nodes of craft skill” that evolved in early modern Europe. The European technological system from the late seventeenth century onwards was founded on the experience-based technological knowledge of pre-modern craftspeople and engineers.Footnote 8

In the last few decades, historians analysing the non-European world, including those focusing on India, have been trying to trace the histories of indigenous useful knowledge and local knowledge to redefine “useful knowledge” so that it is less Eurocentric.Footnote 9 Prasannan Parthasarathi critically examined Joel Mokyr's view that the source of the “Great Divergence” was Europe's deployment of “useful knowledge […] the unique Western way that created the modern material world”.Footnote 10 Parthasarathi points to India's limited historical evidence, for which we are largely dependent on European observers, and argues for the existence of a sophisticated and dynamic culture of technical knowledge in India.Footnote 11 Here, one also needs to take into account David Washbrook's view that the textile economy of pre-colonial and early colonial South India was based on extreme specialization on the basis of caste and sub-caste. Though it was tapped by global markets, Indian innovation remained embedded in local skills, so that the result was not a path to an “industrious revolution” but the production of “luxury in a poor country”.Footnote 12

Examining the nationalist movement that unfolded in parallel, historians have acknowledged that though crafts became a political symbol of Indian experiences under colonialism, the narratives constructed around artisans presented them as traditional, ossified, and homogenized – subjects to be archived and preserved in museums and art schools.Footnote 13 The nationalist response towards colonial modernity and changing consumer patterns – especially a shift to Western clothes and tastes – not only moved consumers away from traditional buying habits,Footnote 14 but also created a peculiar crisis for the Indian handloom industry. Nationalists correctly pointed to the emergence of a colonial style of dress as a key reason for the crisis and linked the impoverishment of India to the urban and colonial elites’ preference for foreign goods. They believed that the survival of the handloom sector hinged on adopting new ideas and actions to remain relevant.Footnote 15

As seen above, historians investigating both Western societies and the colonial world have drawn attention to the dynamics of de-skilling, whereby weavers either forgot old skills or continued to labour using older techniques but subject to the authority of “experts” and alienated from the production process. Existing scholarship, however, tends to overstate the extent to which these transformations led to the demise of weaving work. In India, as elsewhere, a modern focus on “production” – understood as commodity production outside the home – led to a projection of handloom work as “traditional handwork”. In this understanding, as Parthasarathi has argued, tacit knowledge and useful knowledge are seen as fundamentally European. So, it would be useful to examine the idea of “useful knowledge” in a non-European setting by exploring the socio-economic and cultural context of different forms of hierarchies and technologies and their uses.

To understand this relationship between society and technology, it is useful to engage with the “social construction of technology” (SCOT) theory. The concept was set forth by Wiebe Bijker and Trevor Pinch, who argued that technology is socially constructed: not in the trivial sense that machines are designed and manufactured by people, but in the sense that the working of a machine results from social processes and not merely from the application of physics, chemistry, and mechanics. Instead of assuming a single, self-evident chronology of development for a technology, SCOT describes technology as resulting from interactions between different social groups. The first step, then, is to identify which social groups are relevant for a technical development.Footnote 16 Artifacts are interpreted in radically different ways by various social groups, as they are conceived and understood to be different things by different groups. This argument, when extended to the North Indian handloom sector, sheds light on the diverse yet nuanced responses to new technologies.

In the case of South Asia, the most defining factor driving labour organization, and hence the introduction of any new technology, is caste. Two recent works examined the interconnectedness of caste and the technical domain to develop their arguments. Shahana Bhattacharya's analysis of the objectives and social milieu of state-organized technical education in the context of the leather industry and leather training institutes in colonial India shows how entrenched notions regarding the leather industry, particularly its perceived traditional nature and association with low caste and social status, changed. Technical education in leather production had to navigate the extreme stigma associated with hides and skins due to caste on the one hand, and their integration within the capitalist colonial economy and their concomitant high profitability on the other. Decisions regarding who or what were to be taught and by which pedagogical methods were produced through these negotiations. This context defined the Indian leather industry of the time – the functionality of caste made modern technical education a prerogative of educated elite castes while the outcaste labourers continued to carry on degrading manual labour.Footnote 17

Similarly, in their introduction to the Review of Development and Change (2018), S. Anandhi and Aarti Kawlra provide a broad outline of how issues concerning caste and craft critically shaped the discourse on caste and education in colonial India and Sri Lanka. By mapping colonial, missionary, Malthusian, and eugenic discourses on education, they explore different kinds of pedagogical interventions in colonial India and Sri Lanka to unveil the origins of early developmentalist agendas, looking at how caste- and gender-based categorizations of the knowing subject were formulated, naturalized, and resisted. Here, again, we are required to move past simplistic explanations based on the tradition–modernity paradigm.Footnote 18

These examples show that studies on craft must expand their scope beyond the impact of interventions by state regulators, the reformist elite, and commercial providers. Certainly, this sector was constantly subject to governmental controls and interventions for the sake of modernization and developmental models. Historians such as Douglas Haynes and Tirthankar Roy have dealt extensively with questions of artisanal innovation, reallocation of household labour, gendering of production, and innovations in production regimes, which led to centralized workshops in some cases, and greater decentralization in others, in the early twentieth century.Footnote 19 Haynes and Roy clearly show the internal differentiation among weavers more in economic and occupational terms, as some weavers became master weavers (spending little time at the loom) and others were reduced to piece work. As one compares regional variations, adaptation to the powerloom, and wage relations in the urban sites of Western and Southern India was easier than in the rural and semi-urban localities of north. The prevalence of traditional production networks in the United Provinces remained tied to the continuation of strong religious, caste, and local identities. As the economic differentiation among the weavers became explicit in the face of capitalist relations, apparently the traditional “Community” emerged as the key source of resistance to these new forces of change in the United Provinces.Footnote 20 Such collective identities shaped the social and political consciousness and actions of the Julaha weavers; these identities resulted in strong community bonds that overshadowed economic ones even in the face of economic exploitation by “leaders” who played the dual role of community leaders as well as master weavers.Footnote 21

Historiographical attention on the relationship between technology and skill has multiplied in the last few years. There is a growing academic focus on technical inputs in rapidly proliferating formats communicated through informal artisan networks, often under hostile regimes. However, the technologies introduced by colonialism induced not merely a shift in textile production processes, but also an antagonistic environment in which, on the one hand, artisans possessing indigenous knowledge of handloom weaving had to fight for relevance in this new environment through re-skilling, but, on the other, there was also an experience of engagement, interaction, and dialogue.

SURVIVAL OF WEAVING SPACES

The above discussion highlighted the contradictions within colonial modernity; this section further brings out the nuances in encounters of craft communities with colonial modernity, both at the material level (work practices) and at the discursive level. Until the early nineteenth century, the United Provinces produced every variety of fabric known in the cotton sector using local expertise. The figured muslins (jamdani) of Tanda and Jais were worn by the royal court of Awadh. Before the decline in demand, Lucknow weavers produced special silk (malmal and tanzeb) fabrics; however, by the late nineteenth century, they started manufacturing addhi, which was well-suited for fine embroidery using silk and cotton thread, called chikan, or gilt thread, called kamdani.Footnote 22 By this time, competition with the mills and a change in people's habits and tastes led to the decline of the hand-weaving industry. Thus, some localities of the eastern United Provinces focused on silk products and gradually their fame and survival became dependent on silk. In the early 1880s, skilled weavers shifted to specialized silk textiles, including daryai-baf, dosuti-baf, gota, kinari farosh, malmal, tanzeb, etc.Footnote 23 Felt caps were steadily replacing the courtly pagris, while figured jail-matting supplanted the use of printed floor cloths of elegant design. However, due to their superior texture, the muslins of Mau in Azamgarh and of Sikandarabad in Bulandshahr still held their own against foreign imports. Cotton printing was not as affected by the competition as the hand-weaving industry. On the contrary, there was growing demand among Europeans for printed counterpanes and curtains manufactured by the chhipis (printers) of Lucknow, Farrukhabad, and Bulandshahr – a sign of the expansion of trade in these goods under foreign support.

Banaras was widely celebrated for its brocades, being home to manufacturers of silk of every description, from the finest kinkhab, worn by those of rank and nobility, down to the plainest scarf or chaddar, worn by men of moderate means. Agra silks were manufactured using yarn imported from Punjab and Bengal. Mubarakpur in Azamgarh was an important trade centre for satinettes. The town produced two varieties of mixed fabric, known in the local market as sangi and galta. The former, a combination of coloured tasar and cotton, had buyers among the well-to-do classes of the Muslim community, while the latter, a web of silk and cotton, was woven into dress pieces for export to Nepal and Europe.Footnote 24 Due to its specialized nature, the silk industry had a greater chance of survival compared to cotton textiles, since initially it faced hardly any competition from imports, unlike cotton. Because of such adaptions and despite claims that the industry was in decline, a 1908 report estimated that roughly “populations of quite a million were dependent on hand-loom weaving for subsistence”.Footnote 25 Though the number of silk weavers was only in the thousands, many weavers were simultaneously weaving both cotton and silk.

Handloom weaving remained a major occupation in this region and required diverse skills to produce some of the most skill-intensive types of textiles woven on the loom. This strategy of traditional craft communities, of shifting towards silk cloth production, ensured that they continue to receive patronage as elites in cities like the maharaja of Banaras and the local talukdars sought out expensive and well-decorated silk textiles that were not available through foreign trade.Footnote 26 But because of the constant need for capital investment and new designs, and the specialized nature of the industry, the shift towards silk production led to the emergence of new, modern textile firms as intermediaries.Footnote 27 By the early twentieth century, the need for ready money, raw materials, and skilled labour had transformed this sector in line with certain new terms of capitalisation and commodification.

The colonial regime initially introduced many initiatives in the fields of craft and weaving. This period also saw a migration of capital from agriculture to small-scale urban trade. Such processes had created a small urban market for artisanal industries by the mid-1920s, but artisanal products required certain changes to meet the requirements of urban fashion, resulting in a new strategy. There was an urge to modernize and make these professions more appealing to larger audiences as part of the project of colonial modernity. To stay relevant in the face of external competition from machine-made cloth, it was necessary that the community innovate, if not totally transform, its production processes. To this end, everyday survival depended on a number of unpaid as well as paid skills – pre-weaving and post-weaving activities, textile manufacture, etc. – that ensured weavers’ livelihood and self-sufficiency, even in the most oppressive circumstances. However, labour relations based on old and new community categories strained production relations. In a way, both social and production relations were transformed through complex connections between skill, knowledge, capital, and modernity, as explained below.

Gendering Labour

At this juncture, we need to revisit the hidden figures who worked not only as work attendants, but also at the periphery and even outside of weaving communities as spinners and sometimes even as weavers – women. The invisibility of women's work revolves around the intersection of the actual work, the femininity of the occupation, and the marginalization of female labour in the artisanal sector. While initially historiography provided economic explanations for why men were seen as the “breadwinner”, in the 1980s, the terrain had shifted, and ideological explanations focusing on changing notions of domesticity and masculinity gained importance. Samita Sen's study of women in the jute mills of Bengal emphasizes how ideologies of domesticity and seclusion helped create a gendered workforce. She argues that the managers of the mills drew on the discourse of domesticity to legitimize the exclusion of women from the workforce. Thus, for working-class families, seclusion of women came to be associated with respectability and a higher social status.Footnote 28 In the handloom industry, the tussle between tradition and modernity acted in a more complex manner – the women of the Julaha community were so necessary for the production cycle that, purdah requirements, new weaving practices, and shifted production workshops excluded women from the shop floor, yet they continued to work as invisible household labour.

In the United Provinces, women were engaged in weaving on a large scale, though more as an auxiliary force. A huge market and production network required a constant supply of yarn, and here the role of women became significant as a domestic workforce. In the early nineteenth century, the British surveyor Buchanan Hamilton reported that the “good women” of the upper castes supplied raw material, i.e. self-spun thread, to weavers who were then paid for their labour of weaving the thread into cloth.Footnote 29 In 1877, most looms in the Azamgarh district that manufactured coarse cloth did so using yarn spun by women of all castes in all parts of the district. The female spinners, known as kattis, purchased cotton by weight from local traders, and after spinning it into thread, exchanged it either for cash or cloth.Footnote 30

However, the first occupation that suffered due to the European Industrial Revolution and the import of English yarn was indigenous yarn spinning labour market. From the 1830s onwards, cotton and silk cloth production in the United Provinces saw the influx of English twist yarn, which supplanted the use of native thread.Footnote 31 India's emergence as a supplier of raw cotton to Britain led to a series of other changes, the most significant being the decline in hand-spinning of yarn in favour of imported mill-spun yarn and cloth. This not only eradicated the livelihood of millions of spinners (predominantly women), but also brought about significant changes in the organization of the weaving industry over time.Footnote 32 According to a government-sponsored silk survey, “[w]omen of the richer classes spin for amusement and for household use, often meeting and spinning together on the English ‘working party’ principle; while those of the poorer classes spin both for home consumption and for sale”.Footnote 33

By the 1890s, the poor practised spinning as a source of supplementary income rather than as a full-fledged occupation. Women of all castes (old and young), especially poorer women, used their leisure time between household duties to spin yarn. Owing to the competition from power spinning, the wages of such hand spinners were very low, and “only feeble women and those who cannot come out of pardah still practice hand-spinning”.Footnote 34 Hence, spinning was still practised as long as the spun yarn could be sold for a sum greater than the cost of the cotton from which it was spun, mainly in remote villages far from rail connectivity or cities.Footnote 35 Following the decline of spinning, female labour shifted to new avenues such as chikan embroidery, which grew in popularity mainly from the 1860s, particularly in big cities. Chikan embroidery was mainly domestic work pursued by women.Footnote 36

By the early twentieth century, women's work in the handloom economy remained subordinate but complementary to men's “professional” handloom work though handloom weaving as a domestic occupation depended on the use of invisible labour. The real labour cost of hand-woven cloth could not be assessed, as such cloth “includes the earnings of women and children on the preliminary operations of warping and sizing”.Footnote 37 Ideally, “men wove and women reeled”; if either of them stopped performing their gendered division of work, production would stop, and they would starve. The role of women in handloom production was so vital that in Moradabad district in the United Provinces, when the colonial government introduced a government training programme in 1911 to educate weavers on the use of the modern Serampore loom, the officials faced weavers’ resistance.They grieved that women of the Julaha weaver community, who had earlier assisted their men working on the household kargha loom, were no longer able to help their men. This happened because the newly introduced modernized Serampore loom could only be used in large karkhana (big handloom factories) spaces and not at home. Most of the weavers refused to use fly-shuttle looms for this very reason. Thus, the weaving school committeeFootnote 38 recommended a scholarship for “women who will accompany their husbands and learn the use of the fly-shuttle loom”.Footnote 39 However, there was no affirmative action in this regard. In Shahjahanpur, the headmaster of the experimental weaving station, Banaras, and the Industries Department surveyor, J.M. Cook, saw during his visit to several parts of the district in January 1913 that many women and children were at work preparing yarn:

Here, as in other places, the women folk take a large share in producing the cloth. Even when the male member of a family was weaving on a fly-shuttle loom, I noticed there were also “karga” looms on which the women weave.Footnote 40

It was suggested that the zenana school, which ran adjunct to the Tyler Weaving School, have two or three fly-shuttle looms to address the local populace's objections. But no such decision was taken in this regard and the Industry Department continued to promote embroidery among women.

Despite the hold of purdah and other gendered norms on “modern” social spaces, the public sphere was accessible to women to some degree. Contrary to the assumption that women were progressively deskilled, their autonomy undermined by experts, and their work made redundant by industrially produced commodities, there appears to have been an uneven transformation where new skills and technologies interacted with older cultures. How new technologies coalesced with older ones to produce new forms of hierarchies can be traced by examining the changes in everyday handloom technologies. By the early decades of the twentieth century, the positions of men and women, previously based more on skill and labour and less on dependence on capital and technology, were now clearly differentiated in the industry. At the level of the social consciousness of colonial modernity, this gendered regimentation was traced to an imagined past and normalized, so that the weavers and their women accepted this situation without serious complaint.

COLONIZATION OF WEAVING

In the history of this indigenous industry, colonial interventions represent a paradigm shift in the way knowledge of technologies was formed and applied. The modernization of the weaving industry of the United Provinces was highly contested, reflecting the tensions between the superstructures of modern knowledge and their application to indigenous skills. The desire to rehabilitate traditional “communities” and their occupations was recognized as an ultimate expression of the power of modern knowledge. The colonial regime offered technical alternatives in the form of new syllabuses, modes of transmission, and enhancement of knowledge and motivational structures. But existing traditional and complex knowledge, transmitted through kinship and close-knit community groups, held its ground, protected by existing power relations. How both the systems interacted, co-existed, challenged, and overlapped with each other in response to new ground realities and, in the process, transformed each other will be discussed here.

The general feeling among the officials was that the traditional handloom industry was backward and unproductive, that even the working conditions of the weavers were primitive, requiring step-by-step improvement and industrialization. The official reports, however, also acknowledged that downward filtration of the development model in a patronizing manner would not be acceptable to the weaver community. Officials were wary of the weavers’ “fanaticism” and “bigotism” as well as of their “backwardness” and “ignorance”.Footnote 41

Pedagogical Concerns

Sir John Hewett, the lieutenant governor of the United Provinces, mooted the idea of opening weaving training schools in a Conference on Industrial Development in the Province organized at Nainital on 31 August 1907. The conference recommended that the government intervene in the weaving industry. In response, the government set up an experimental cotton weaving station at Banaras. At this weaving station, workers were paid daily wages, subsequently combined with piece-work wages, and only students with a practical knowledge of weaving were admitted. A school for apprentices paying a fee was set up as well. A silk-weaving school was attached to this cotton-weaving station. In addition, small demonstration stations were established at Tanda, Moradabad, and Saharanpur to popularize simpler, improved processes of warping and fly-shuttle weaving. Each such station was managed by a skilled weaver reporting to a local administrative committee. Part-time primary schools for trainees were also opened at each station.Footnote 42

During this phase, the colonial government emphasized the establishment of “small, private, handloom factories of a size not exceeding 100 looms in each – so as to be large enough to command the market for production and to admit the use of improved appliances for sizing and warping and for personal methods of sale – without requiring the use of large capital”.Footnote 43 The director of the Industries Department, W.R. Wilson, personally preferred this system, as, in his opinion, it was “from a similar system that the English cotton weaving industry took its rise”.Footnote 44 Thus, the English model of industrialization guided industrial development in the United Provinces. In April 1912, the Department of Industries assessed the effectiveness of these schools in improving the handloom cottage industry, and felt that “considering the sceptic nature of the weavers, their old prejudices and their poverty the success so far attained by these schools is not little”. The officials also believed that the weavers would “perforce give up their antiquated methods of work and will resort to improved methods and appliances to ply their profession”.Footnote 45 But in a statement to the secretary to the Government of the United Provinces, the director of the Public Instruction Department reported that:

The point which causes misgivings is the reluctance of the weavers to invest in improved looms because they fear that there will be no market for their increased output. It is noticeable here and in Bombay that those who have purchased improved looms are deliberately restricting their output. It is very doubtful whether the explanation – the ingrained laziness of the weaving class – is the true one.Footnote 46

These doubts about the weavers’ perceptions were echoed by Wilson. He accepted that the weaving schools were making slow and difficult progress, owing to differences in local conditions and the pace of progress among weavers, necessitating that each school adapt to local needs. For to this reason, each school helped weavers establish better looms and equipment in their homes, even though the equipment preferred by each school varied according to local conditions. The appliances they showcased were suitable for both household use as well as in small factories accommodating four to twenty handlooms. He acknowledged how difficult it was to induce weavers to take advantage of the schools, effectively supervise their instruction, and assist them in establishing improved looms in their homes after finishing the course. But he believed that these difficulties arose mainly from weavers’ prejudices and not from financial objections. According to Wilson, the weavers readily acknowledged the advantages of the improved looms; however, they were hesitant to invest in a loom that turned out two and a half to four times as much cloth in a day as their existing loom, “on the plea that they [had] no use for so much cloth and [could not] sell it”.Footnote 47 He also cited examples from the Bombay Presidency, where a weaver using an improved loom would work only as long as needed to turn out the same quantity of cloth as before, and then he would remain idle instead of working the same number of hours as before to turn out more cloth.Footnote 48

The failure of the weaving schools was due to more factors than the “conservatism” of the weavers and the “interventionist” approach of the state. In 1912–1913, the headmaster of the Experimental Weaving School, Banaras, conducted an inspection of all the weaving schools across the United Provinces by visiting each school twice within a span of six months. The inspection committee was unable to see the weaving schools “as [an] unqualified success”. The Department of Industries had prioritized “improvement” in the existing techniques over the complete modern “development” of the handloom industry. Before attributing the failures to “obscure economic causes”, the authorities discussed the methods of instruction and the role of existing organizations. The report emphasized that, “[u]nless a sympathetic interest is taken in a student's future career and unless he is encouraged to apply to schools in cases of difficulty or when requiring employment, the weaving schools will never produce any real impression on the textile industry”.Footnote 49 The lieutenant governor of the United Provinces, J.P. Hewett, noted that the greatest difficulty was getting a handloom that used improved methods without compromises on lightness and cheapness, as “many of the so-called hand looms of recent invention are really imitation power looms and much too dear”.Footnote 50 At the Banaras Weaving School, the looms were divided into three categories: pit looms with fly-shuttle sley; frame looms; and pedal looms manufactured by Messrs. Hattersley and Sons of Keighley, Britain. There were also a number of frame looms fitted with dobby or jacquard machines in the weaving schools, but these remained unused. The weavers had no objection to the pit looms or the frame looms, but the pit looms produced very narrow cloth, which did not leverage the benefits of the fly-shuttle sley mechanism. Hattersley looms were a light power loom, modified to be worked with a treadle. They were trialled in many parts of India but were a hopeless failure as the physique of the average Indian weaver was not sufficient to drive these looms for more than a short time. A single power loom driven by an electro-motor may have been feasible, but a power loom driven by an ill-fed worker was “an absurdity which could only be perpetrated in an educational institution”.Footnote 51 Hence, it is no wonder that the director of the Industries Department noted that Banaras, in spite of being this region's most important weaving centre, was “the district in which we find it most difficult to enlist any sympathy from the weaving community”, referring to the response of weavers to the government training programme.Footnote 52

In spite of all the criticism regarding the weavers’ backwardness, the Indian Industrial Commission noted in 1916 that while “[the weavers] work[ed] under conditions which they prefer[red] to factory life”, many weavers did use better raw materials (such as British mill-spun yarn, which they had adopted in the nineteenth century) and superior tools (like the fly-shuttle sley). The commission admitted that, “they are by no means so primitive as they are usually depicted”.Footnote 53 The Industrial Commission noted that handloom weavers required assistance “not so much in the matter of improving the technique of these methods as in marketing the production of his looms […] why there cannot be an equally good organization for the sale of hand woven goods is a question which requires to be investigated”.Footnote 54 By the 1920s, official records started attributing the technical backwardness of the weavers not to “the community's backwardness”, but a lack of opportunities, knowledge, and capital. Instead of focusing on technical skills, the Census Report of 1921 observed that “the cottage craftsman has no capital and no business capacity. These things must be supplied from outside; and where the industry is flourishing they are so supplied”.Footnote 55 An independent source, the Pioneer newspaper, while highlighting the plight of weavers, did not pay much attention to technical education; rather, it focused on trade conditions and fluctuations in yarn and cloth markets. Marketing was seen as a major problem.Footnote 56 Daily wage workers could not give up their work to learn new methods. Their poverty and the need to meet day-to-day household needs were seen as major barriers to learning new techniques.

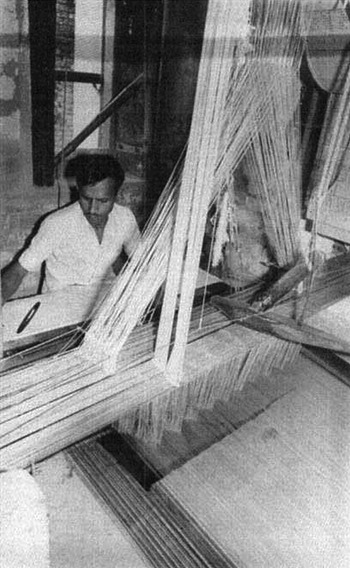

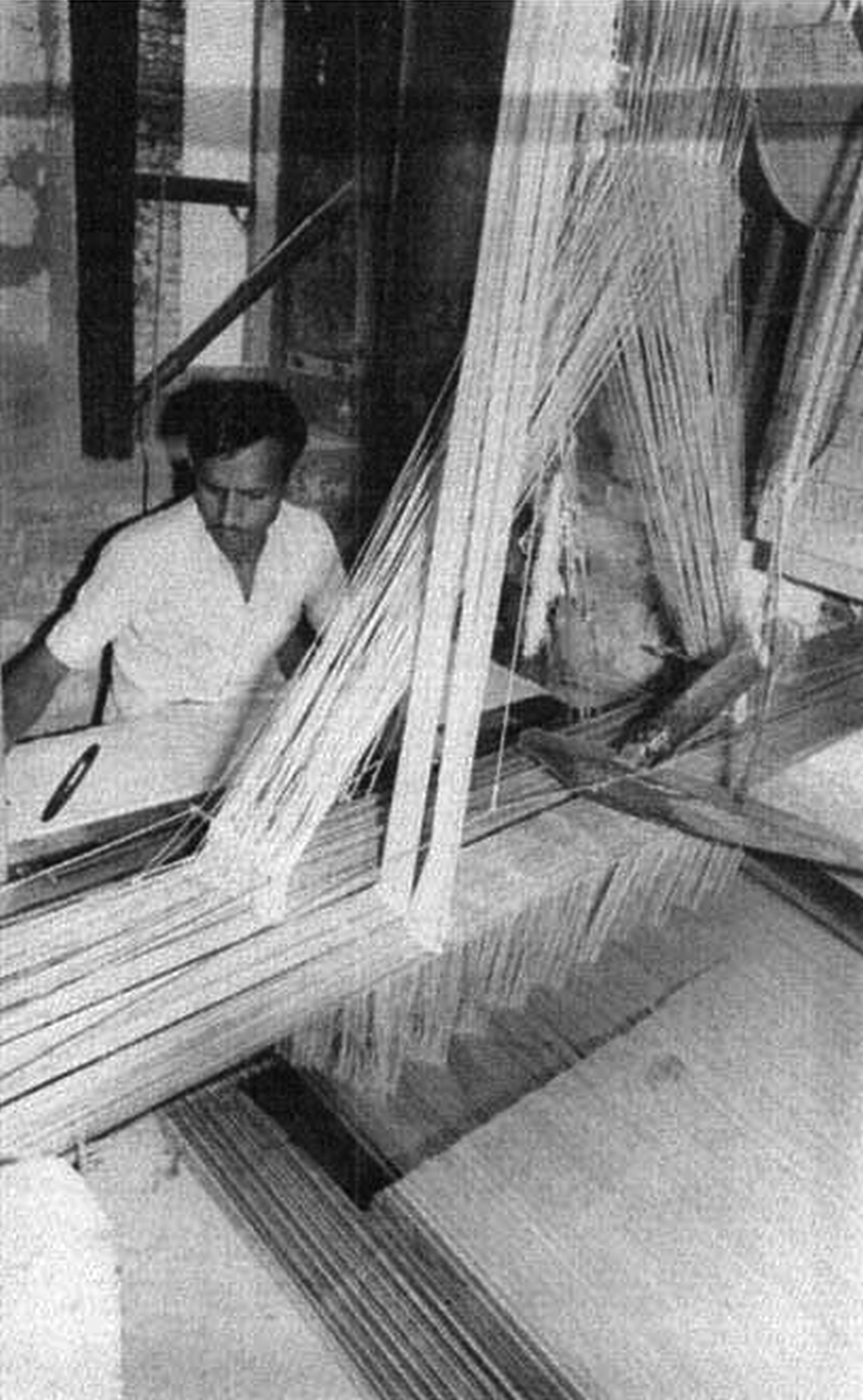

In 1929, the Hattersley domestic foot-powered loom was refashioned, but it took time to gain popularity as weavers found it difficult to constantly pedal to operate the machine.Footnote 57 In contrast, the Malegaon handloom procured through personal efforts was quickly adopted by Barabanki weavers producing heavy fabric, negating the perception that weavers were inherently resistant to change.Footnote 58 Weavers’ willingness to innovate and appropriate improvements is likewise reflected in the widespread adoption of the Mohajit (Mahjit) loom by the rural weavers of Chiraigaon in Banaras. The Mohajit loom offered certain advantages over the existing desi and fly-shuttle looms. The loom utilized a better swinging arrangement, of which the sley was the most important part. The sleys of traditional handlooms swung on knife edges that were held in grooves cut into an iron plate and fixed on the loom frame (Figure 2). But with the new technique, looms swung on an iron rod that rested on grooves cut in the wooden frame of the loom. This system was found to have a significant drawback – the iron bars were not strong enough to support the weight and working action of the sley, leading to bending of the bars and dislocation of the sley, in turn resulting in inferior quality and reduced production. The grooves in the wooden frame of the loom would also give way and widen, dislocating the sley. The sley's movement was not as free as it ought to have been either, resulting in the workers tiring quickly.

Figure 2. Early twentieth-century handloom.

Photograph Carly Fonville, 1981; with permission.

The Government Central Weaving Institute, Banaras, experimented with various types of looms to improve productivity, including the local innovation, the Mohajit loom. However, as a letter from Dwarika Singh, head mudarris (teacher) of Chiraigaon shows, owing to a lack of funds, further work on improving the local Mohajit loom could not be continued.Footnote 59 The colonial government took a limited view on technical education that did not pay attention to the overall context of the weaving industry and “community”. The government authorities framed their work and their reports within the tradition/modernity dyad without adapting their efforts to local work cultures to attain compatibility, contentment, and adaptability in training as well as upgradation of the weaving industry.

Exhibiting Modern Knowledge

In Britain, the Arts and Crafts MovementFootnote 60 used art exhibitions to shape consumer habits and public taste. It also helped democratize public spaces through gendered strategies implemented by women.Footnote 61 In the case of India, in the 1880s and 1890s, British officials worried that traditional Indian designs were disappearing in the face of rapid Westernization. But their idea of what constituted “traditional” designs was itself new, forged first at international exhibitions and then in the context of Indian artisanal and consumer experimentation with novel combinations of foreign styles and objects. Indeed, it was the latter that prompted British art officials in India to call for a return to tradition. But traditionalism in design was not just a reaction to Indian cosmopolitan tendencies; it tried to achieve its own, slightly different cosmopolitanism by Indianizing Western forms.Footnote 62 However, such craft exhibitions were also used to display and demonstrate the use of modern looms and skills and included weaving competitions.

The first such demonstration of the skills of the handloom weavers of the United Provinces was at the 1835 Lucknow exhibition – it featured the Mauwaal weavers (weavers from Mau living in Banaras). Another such interaction between modern techniques and traditional weaving skills was seen in 1902, when the Banaras weavers presented their brocades and saris along with their techniques in an industrial exhibition in Delhi.Footnote 63 The Banaras Silk Weavers’ Cooperative Association also sent its goods to annual exhibitions in Hardoi and Sultanpur and the Nauchandi fair at Meerut.Footnote 64

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the government of the United Provinces started organizing exhibitions to encourage and improve the handloom weaving sector. Various modern looms were displayed at these exhibitions and weaving competitions were also held. However, the demonstration of the fly-shuttle loom at the 1905 Banaras Industrial Exhibition failed to arouse a positive response among the weavers of Banaras.Footnote 65 J. Hope Simpson, the registrar of the Co-operative Credit Societies in the United Provinces, tried to interest the Banaras Silk Weavers Co-operative Central Association Limited in the improved handlooms, especially for the production of Kashi silk. For this purpose, he arranged that association members visiting the handloom section of the 1905–1906 Banaras Industrial Exhibition could enter for free. About a hundred weavers took advantage of the concession and carefully inspected the fly-shuttle looms. However, the silk weavers did not approve of these looms. Three months’ careful training was required before a weaver was competent to use a fly-shuttle loom effectively, during which time he would not be able to earn anything. Very few weavers were financially able to contemplate three months of unpaid work.Footnote 66

The registrar of Cooperative Societies again obtained permission for a number of weavers to visit another exhibition (held at Allahabad) and inspect the handloom free of charge. However, they criticized the fly-shuttle loom (of which there were many versions at the exhibition) as it would not be able to weave cloth of the breadth of Kashi silk, i.e. fifty-four inches. However, the leaders of the association highlighted its advantage: the ability to weave 120 or 130 instead of thirty-five or forty picks a minute, and stated that, “if a loom for fly shuttle with silk is in existence which will weave cloth fifty-two inches wide they will be eager to adopt it. Indeed they expressed their willingness to purchase and advance such looms to workers recovering the cost in instalments out of the price of the cloth”.Footnote 67

Modern textile mills soon became exemplars of their particular working models. Some of these exhibitions were sponsored by the Elgin Mills Company and the Muir Mills Company of Kanpur. The idea of exhibiting company looms and having weavers compete with mill products for the purpose of “judging” their work was rather patronizing. One such exhibition was organized at Allahabad during 12–18 January 1911. A key objective of this exhibition was “having the work [as well as the exhibits] judged in a thoroughly technical manner”. The exhibition also included prizes for various categories, including a prize of Rs. 70 for the best loom in the category of improved fly-shuttle looms affordable for a village weaver, for the best exhibited loom, and for the weaver doing the best work.Footnote 68

The competitors brought their own looms and warp while the organizers supplied the yarn. To practice, weavers could weave a length of cloth not exceeding two yards. The factory working hours were strictly observed, and work of any sort was not allowed in the weaving sheds at any other time. The principle of “one man to each loom” was also applied, and competing workers seeking assistance from anyone else were disqualified.Footnote 69 Given these rules, the reasons why attempts to modernize the weaving industry failed were self-evident. Traditional weavers rarely followed the disciplined “working hours” of a factory and an indigenous loom required at least two persons to work it – the main weaver and an assistant, usually a child apprentice. The looms were judged based on their improvement on prevalent village practices, ease of setting up an operation, and cost effectiveness; warping and uniform picking of yarn for both rapid weaving and regular work were taken into consideration, too. There were two competition categories:

(i) work done on the indigenous village loom, and

(ii) work done on an improved handloom, either of Indian or foreign design.

During the whole period of the exhibition, the improved handlooms were shown in operation during working hours.

Some competitors withdrew after registering their names – perhaps due to their apprehensions regarding the fairness of the rules and impartiality in judging. One weaver withdrew due to a fear of being “out-classed by the looms and weavers on the site”. Such fears were not unfounded. The competition was meant for the weavers of the United Provinces, but they were treated as inferior to weavers from the Madras and Bombay Presidencies in terms of technical skills. The organizers rued the absence of Madras and Bombay weavers to demonstrate “what really a good weaver can do”. Even within the United Provinces, the largest group of competitors came from the Hewett Weaving School, Barabanki. Thus, for the organizers, the parameters of “skill” were predetermined in favour of “modern” models of knowledge, and they aimed to motivate the indigenous village weavers to get trained and pursue the same goal of excellence and forsake their existing knowledge. Evaluation was based on the “actual working, design and probable performance in skilled hands of the looms – as judged by the actual master weavers, mainly”. The traditional weavers’ skills in producing superior quality textiles were considered inadequate to begin with, so the criteria for winning the competition were based on turnout alone, which was necessarily insufficient in the case of skilled and incorruptible weavers, who focused more on quality.Footnote 70

At the exhibition, the whole idea was to showcase the advantages improved looms offered in terms of producing more and earning more. The “picks per minute” taken by the loom in a length of cloth was one of the parameters for performance, which naturally made pit looms look inferior to frame looms. C.A. Sherring, the deputy commissioner of Barabanki, argued that a “man cannot do such good work, or keep such good health when sitting on the ground with his legs below ground level, as he could if raised above the ground”.Footnote 71 However, no evidence was offered to the weavers in support of the allegations that quality of work and health suffered. Consequently, they refused to part with tools that had been in practice for centuries.

In the grant-in-aid allocation for 1912–1913, Rs. 500 was sanctioned for the demonstration of improved looms at local fairs and exhibitions. The district magistrate of Azamgarh was expected to revive the school at Mau, which would begin functioning again either in the same town or be relocated to a nearby place with more local support in favour of new technologies.Footnote 72 The peripatetic (on-site instructional system) schools for hand weaving were also adopted, taking a cue from Madras and Punjab. Publications of the Government of Madras indicate, however, that it had to abandon similar experiments since the expenditure entailed was not commensurate with the results. Nevertheless, the Government of the United Provinces decided to go ahead. The idea was to display the winning looms from the exhibitions in towns and villages in the United Provinces. There was a favourable response from local governments, which hoped that exposure to novel and cutting-edge technologies – typically available only to towns and large trade centres – would be offered to villages and small settlements as well. Initially, only demonstrations at big melas (fairs) and provincial festivals were attempted.Footnote 73 Within a few years, the peripatetic schools proved to be more popular than the stationary weaving schools. In 1915, the weaving school at Deoband was closed and replaced with two peripatetic classes with highly satisfactory results.Footnote 74 The Banaras weaving station set up three demonstrations during 1914–1915: the first in Banaras; the second at the Dadri fair in Balia; and the third at Tanda. These were in addition to the usual district-level exhibitions.

Moving the demonstrations and training out of the schools to the weaving communities’ own spaces proved a more successful tactic.Footnote 75 In the peripatetic school at Alaipur in Banaras, the instructors started holding night classes on their own initiative. This was convenient because the professional Julahas could not spare time during the day (not a single daytime trainee was a weaver by caste), and yet they required practice operating the fly-shuttle looms to sharpen their skills, since they already knew the basics.Footnote 76 So, for a short while, when a branch school in the weavers’ quarters was opened, “it was attended by sons of regular weavers […] it also had great success in popularizing improved looms”.Footnote 77 The household livelihood was so precarious that it was not possible for a common weaver to be a full-time trainee.

The Nationalist Vision

Indigenous responses to the government took various forms: first, modernizing weaving became part of the nationalist agenda; subsequently, nationalists attempted to establish alternatives to government schemes. The nationalist party, Indian National Congress, recognized that the decline in India's indigenous industries was a principal issue under its Swadeshi plank. It lobbied for instituting a comprehensive industrial survey of India as a preliminary measure before introducing an organized system of technical education and adopting measures to resuscitate old industries and bring into existence new ones. At the Lahore session of the Congress in 1900, an Industrial Committee and an Education Committee were appointed to consider and recommend practical measures to drive the development of industries and the spread of education. But the committees never reported back to the Congress on either matter, and they were not re-appointed at the next succeeding session. In its attempt to showcase Indian culture, the Reception Committee of the Calcutta session of the Congress in December 1901 organized a small exhibition of Indian industries as an adjunct of the Congress session. Leading members of the landed aristocracy of Bengal, like the maharajahs of Mymensingh and Kasimbazar, were members of the sub-committee that made arrangements for the exhibition, while the leading Indian ruling chief of Bengal – the maharajah of Cooch Behar – presided at its opening ceremony. The objective of the exhibition was to open the eyes of educated Indians to the condition and possibilities of India's manufacturing industries. It also led, as its immediate practical outcome, to the establishment of Indian Stores Limited, Calcutta, which exhibited and sold indigenous articles – a step calculated to stimulate a demand for handmade goods from India and subsequently increase their production.

At the First Industrial Conference held in Banaras in 1905,Footnote 78 Rao Bahadur Raojibhai Patel lamented that “the Indian hand-loom as it now is, is the same as it was some thirty centuries ago”.Footnote 79 Similar views expressed by renowned European vocational educationists strengthened the nationalist position. At the same industrial conference, E.B. HavellFootnote 80 observed that a key problem in shifting from handloom to power loom in the Indian context lay in the comparative affordability of manual labour over mechanical power. In Europe, mechanical power was cheaper than labour, and so the power loom could drive the handloom out of the market; but in India, due to the low cost of manual labour, the handloom could compete successfully with the power loom.Footnote 81 Initially, nationalists favoured the colonial vision of innovation and a shift to the power loom, perhaps due to shared notions of modernity. At the First Industrial Conference of 1905, renowned economist and administrator, R.C. Dutt, accepted that “the dignity of man is seen at its best when he works in his own field or his own cottage”; but remarkably, he recommended that “we must change our own habits of universal cottage industries, and learn to form companies, erect mills and adopt the methods of combined actions if we desire to protect or revive our industries”.Footnote 82 This passionate view in favour of modern techniques and methods did not account for the fact that traditional handloom weaving was conditioned more by ground realities than choices.

In later stages of the nationalist movement, an alternative view emerged that differed in tone and actions, but likewise failed to inspire hope among traditional weaving communities due to its use of symbolic practices and push to empower every Indian to use the spinning wheel. Such nationalist attempts to build an alternative to colonial policies proved to be selective in terms of economic targets without any major outcome for the handloom industry in long-term. Gandhi's acts could be better explained within a framework of cultural revivalism, as he said, “I feel convinced that the revival of hand-spinning and hand-weaving will make the largest contribution to the economic and the moral regeneration of India.”Footnote 83 Gandhi, in his endeavour to construct national symbols, tried to establish a balance between “tradition” and “modernity”, flagging that India needed both to establish its legitimacy by virtue of incorporating tradition and to adapt its culture and economy to compete in the modern world. He shifted the focus of the Swadeshi programme from weaving and handloom cloth to hand spinning and khadi, leading to a unique politicization of crafts. In his writings and speeches, Gandhi was conscious of his choice of spinning and the charkha over other crafts and even over the handloom. His charkha promoted a special type of khadi cloth production and almost suffocated numerous other varieties of traditional handloom cloth and spinning. The impact of his proposed alternative can be seen at the organizational levels as well, when the All-India Khaddar Board was established in 1922 (renamed as the All-India Spinners’ Association in 1925) for the purpose of providing technical instruction, facilitating the collection and distribution of yarn supplies, regulating quality, certifying authentic khadi dealers, and promoting khadi products.Footnote 84 This Gandhian move of supporting the production of only plain, coarse material further marginalized traditional artisans capable of producing very fine cloth. His model empowered everyone to learn spinning, effectively denying the need for artisanal expertise.Footnote 85 Gandhian attempts to refashion both tradition and modernity within a specific schema of cloth production and modern fashion proved detrimental to the handloom sector.

At the ground level, craft skills were also influenced by nationalist–colonial conflicts. During the Non-Cooperation Movement in Banaras in 1922, a confidential letter was circulated advocating the establishment of spinning schools supported by muthia collections (grain donations). The Indian National Congress started spinning schools adjunct to Gandhi ashrams in villages. The nationalist scheme aimed to have one handloom weaving school to every ten villages. A bicycle force was organized to train and mobilize artisans. Similarly, in Gonda, a weaver from Azamgarh was invited to teach weaving in a factory owned by nationalist Prabhu Dayal and others.Footnote 86 Police informers suspected that these weaving schools were used as a cover for secret societies.Footnote 87 Whenever conflicts over ways of appropriation of modernity emerged between the colonial regime and nationalist movement, common weavers generally opted to stay away from such politicized experiments that harmed their personal interests. Beyond the duality of colonialism and nationalism, weavers adopted certain measures and ignored others, according to what worked best for them.

TRANSFORMING THE WORK CULTURE

The new working conditions resulting from technological shifts, the shift to silk weaving, changes in production organization, the rise of weaver capitalists, and the need for new strategies forced weavers to renegotiate with the means of production. By the twentieth century, the silk artisans of Banaras were all Julahas but divided into three different classes. There were, firstly, those who worked for wholesale and retail dealers and did not belong to the weaving class; then came those who worked in the bazaar or local market and sold their own goods themselves; and finally, there were those who worked for factory owners or karkhanedars – richer members of the Julaha community.Footnote 88 The brocade workers were almost all in the third group, while the first two classes comprised the sari and duppata and Kasi silk weavers. In almost all the cases, the yarn was procured from a dealer rather than being directly imported by the karkhanedar. The same system of procurement was used for acquiring gold thread. The artisans working for wholesale dealers were dependent on middlemen who advanced the yarn and procured the manufactured product either as a purchase or commission sale.Footnote 89 The Banaras silk weaving industry and its allied trades – gold and silver wire, kalabatun (gold thread), etc. – depended on these broker networks. The weavers were entirely dependent on these middlemen who supplied them with silk and other required materials and then sold the finished article to wholesale dealers. The middlemen regulated the price of raw materials and of the finished products of the weaver. Common weavers were so exploited in this system that improving their workmanship or trying out new designs was impossible. Some limited initiatives were introduced by the government to ensure proper and regular supply of raw materials at fair prices as well as to introduce new marketing practices to increase direct contact between weavers and the purchasing public.Footnote 90 Thus, networks of community-based mediators proved to be simultaneously economically extractive and socially inclusive institutions in the interplay of the institutional and technological impetus towards globalization on the one hand and countervailing localizing forces on the other.

Handloom weaving more or less remained embedded in household labour, but its product sale as well raw material procurement was subject to market forces. The entire community chain of Julahas engaged in the process of handloom production in this micro-region was subsumed within the new model of commodity production. The emergence of capitalist conditions forced new connections, affiliations, and exclusions in the social relationships of production-oriented communities. In labour-intensive, low-cost production households, the structure of the production process was defined by the need to purchase yarn and meet the living expenses of the weaver and his dependents while the cloth was being woven. Marketing of products too was dependent on small capitalists (karkhanadar/grihasta). In response to such changes, the previous community bonding was replaced by the new social power balance, and family ties (husbands and wives, parents and children) were reinterpreted through the lens of work in labour markets. Since knowledge of the loom and weaving was necessary in the new order, the master weavers were all from the weaving community and were Muslim as well. The mechanism of advances and the karkhanadar's/grihasta's economic and social stature in the community ensured their profits but common weavers/labourers living under the constant moral and social pressure of their community superiors were exploited under “capitalist relations”. Thus, the Julaha weavers domesticated the threatening prospect of “proletarianization” by embedding emergent wage labour based social relations within “religious”, “community”, and “kinship” ties (the non-wage labour context of the locality). In the process, Julaha weavers reconfigured both their “religion” and “community” as a “capital” to invest in.Footnote 91

A major issue that shaped the nature of production relations was the lack of local sources of raw material, as the United Provinces was not known for raw silk production. So, the yarn most in demand was mostly imported. Most silk weaving centres in the United Provinces obtained their supplies from European countries through Bombay. Italian silk yarn amounting to forty-three tonnes was imported into India in 1907 and practically all of it was shipped to Banaras. The Italian firms Messrs. Parker, Sumner and Company of Milan and Messrs. Bettoni Gorio (the Bombay agents) were the main suppliers, but it was difficult to negotiate a cheaper rate with them as all the Italian mill owners had formed a cartel and hiked yarn prices. Attempts were made by the Banaras Silk Weavers’ Cooperative Association to contact the manufactures of kalabatun and goati (gold and silver threads) in France and Italy. However, these European manufactures already had agents in India and thus were unable to sell directly to the Banaras Association. All transactions in India had to go through their existing agents.

Government officials saw this dependence on imported raw material as a hindrance to the rapid development of the industry. The Department of Industries tried to introduce British-spun silk to reduce the weavers’ dependence on Italian yarn. However, the problems were not limited to the procurement of raw material. The textile market was no more merely a local market, but part of a global exchange market. The director of the Cooperative Department tried to introduce a new kind of kashi silk to the English market through a British company – Messrs. Coles, Son & Company. A consignment of twenty-one pieces from the United Provinces was sent to Messrs. Coles and they expressed their appreciation for the quality and careful weaving of the material, but after many trials, found that there was no market for it in England. Consequently, this consignment had to be returned to the association.Footnote 92 There were many such failures.

The European monopoly quickly came to an end as new entrants made their way into the Indian market. The increased import of cheap Japanese silks and artificial fabrics to India in the mid-1930s had a twin effect on the weavers of Banaras, Mau, and Mubarakpur. Initially, these imports did not affect them, as both their products and designs had their own niche markets, distinct from that of Japanese goods. However, Banaras handloom silk weavers soon encountered decreasing demand with increasing competition from low-priced Japanese and Chinese artificial silk. To stay viable, they gradually switched to importing the same cheaper silk yarn used in these imports and were able to produce fabrics at lower cost. Some Banaras dealers specializing in Kashmiri and Bengali silk yarns suffered heavy financial losses from the alleged “dumping” of Japanese organza, tram, and other silk yarns in the domestic market.Footnote 93 During the same period, however, the demand for specialized Banaras silk to be used in social and religious ceremonies began to pick up and the silk industry revived.Footnote 94 Thus, handloom silk weavers of the region fared better than cotton weavers. At the same time, silk suits and shirts produced in Bombay and Punjab sold better than the United Provinces’ products, as their finish was better.Footnote 95

As far as consumption of raw materials was concerned, Japanese artificial silk yarn emerged as a growing competitor to Indian silk and cotton yarn. By the late 1930s, the market was saturated with fabricated and duplicated foreign products, which devalued the expertise and quality of indigenous weaving. Embroidered and printed Japanese crêpe saris began competing with handwoven silk saris from Banaras, in spite of the fact that the local weavers did their best to introduce new designs. Now, the ordinary garha (coarse cotton cloth) and dosuti (double yarn thread) textiles were utilized in a new style of printing for export trade, thereby increasing the demand for these fabrics. In Azamgarh district, the government-established Mau textile store remained the centre of garha and dosuti trade. One major innovation was the revival of moonia and dugabia (mutli-coloured yarn) cloth in the form of saris, which had been earlier abandoned for want of patronage.

Trades that played an auxiliary role in handloom weaving were also affected. By the first decade of the twentieth century, aniline dyes began replacing traditional vegetable dyes.Footnote 96 Subsequently, the indigenous dye industry, probably more than any other associated sector, felt the effects of modern technical progress. Colouring textiles using vegetable dyes was a laborious and lengthy process with uncertain results; the use of imported synthetic dyes greatly shortened and simplified the operation and ensured better results, thus enormously reducing the cost of textiles. Many traditional dyers were forced to seek other means of livelihood. During World War I, when the cost of synthetic dyes became prohibitive, attempts to replace them led to a situation where vegetable dyes were almost incapable of meeting the demands of the industry, both in terms of quality and quantity. Further, changes in taste brought about by the use of brighter synthetic dyes made it difficult to find a market for the thinner and duller colours of vegetable origin.Footnote 97 Owing to the prohibitive price of silk dyes during World War I, the Banaras Silk Weavers’ Cooperative Association incurred heavy losses and had to be finally liquidated.Footnote 98 Yet, even in the 1920s, handloom weavers were sceptical about the use of artificial colours – they were so strongly opposed to these that “[the] Julahas used to outcast[sic] if any of them [peers] used aniline dyes”.Footnote 99 This social control over the use of colours may have been an attempt by community leaders to maintain the dependence of common weavers on them.

New designs were also seen as a crucial factor in the success of the Banaras handloom industry. The weavers told J.P. Hewett, the lieutenant governor of the United Provinces, that their customers were asking for new designs, but the initial cost of transferring a design from paper to the thread frame was prohibitive. The government officials, otherwise sceptical about the outcomes of any intervention involving the same group of Banaras weavers, felt so encouraged by this demand that the establishment of a school of drawing and design was recommended.Footnote 100 In 1914, a demonstration of the use of the jacquard loom to weave an intricate Banarasi silk cloth by T.P. Ormerod, the European principal of the Experimental Weaving Station in Banaras, evoked some interest among the weavers. It was not until 1928 that the jacquard machine was actually used for designing handloom textiles in eastern parts of the United Provinces, and the more elaborate designs still relied on older techniques. By now, the designers were doing brisk business selling new patterns and designs. In Mau, one assistant designer exclusively worked on sari border designs required by weavers. “Shadow cloth”Footnote 101 was being used in modern designs and most centres took up this work. The Industries Department report of 1939 noted with satisfaction that 107 new designs had been introduced during that year.Footnote 102

Exhibiting a keen understanding of the market circumstances and by planning their own thoughtful and collective responses, weavers showed that they were not merely objects of larger historical processes. There emerged very dense and sophisticated worlds of labour (and knowledge) around which whole communities’ economies were organized. The dynamics between skills, handicrafts, technology, hierarchies, and the colonial state's tackling of these constantly shaped the interaction and mutual constitution of colonial and indigenous narratives.

Moments of Resistance

The weaver community did not remain a mute witness to larger forces of change, such as the global economy, trade wars, tariff duties, the institutional mechanisms of the colonial state, and the nationalist leadership. Community solidarity was changing as a result of changes in their economic reality. However the forces of change did not remain unchallenged. Weavers made several attempts to organize themselves to resolve their grievances against such larger circumstances, ultimately leading to the establishment of All India Momin Conference, the national body of the Muslim Julaha weavers, in 1926. In April 1923, police intelligence reports from the Adampura ward of Banaras record the formation of a panchayat, or a local council, as the first step towards the soviet plan of establishing a workmen's council.Footnote 103 In 1927, the Dhobis (washer caste) of Tanda went on strike for higher wages – large numbers of this caste were also involved in cotton printing. However, the Industries Department ignored issues related to wages in the informal labour sector. Thus, none of the auxiliary professions related to traditional weaving received support to continue their work for the handloom sector.Footnote 104

In 1926, the Intelligence Department reported that known nationalist leader Maulana Azad Subhani was trying to organize an All-India Muslim Labour Union in Moradabad. Though he could not find much support or encouragement among local Muslims, he established one such anjuman (association) among the butchers and another among the Julahas. The report stated that “the main object of this organization was the social and religious improvement of lower-class Mohammedans”; however, this move acquired a religious overtone as a notice was circulated “warning Hindus against the Mohammedan movement which is to be used for the boycott of the Hindus”.Footnote 105 Azad Subhani adopted the symbol of the garha, or hand-woven coarse cloth produced mainly by the Muslim artisans, as the symbol of his political organization representing Muslim working-class groups throughout the United Provinces. In tandem, Maulana Subhani spearheaded a campaign to boost the market for garha and to revive its production. He saw the garha movement as a means of reversing the depressed economic conditions of Muslim weavers, which he argued had led to extreme poverty and the destruction of the independent artisanal status particular to them. Subhani also attributed the decline in the status of Muslim weavers to British rule and urged them to fight against imperialism.Footnote 106 The All-India Momin Conference also took up the cause of the indigenously produced garha. The emphasis on indigenous handwoven cloth brought the Momin Conference closer to the position of the Congress and its drive to promote swadeshi goods.Footnote 107