No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

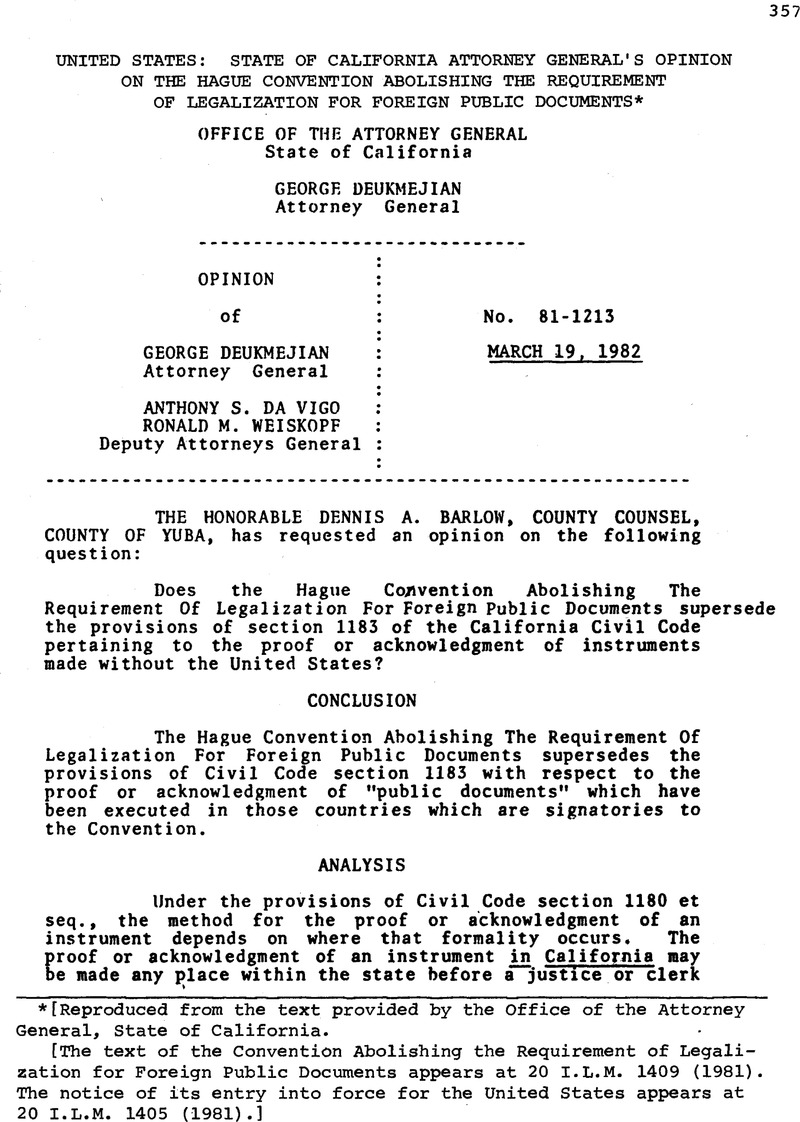

United States: State of California Attorney General's Opinion on the HagueConvention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalization for Foreign Public Documents*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1982

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the Office of the Attorney General, State of California. [The text of the Convention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalization for Foreign Public Documents appears at 20 I.L.M. 1409 (1981). The notice of its entry into force for the United States appears at 20 I.L.M. 1405 (1981).]

References

1 The multilateral Convention adopted at the NinthSession of The Hague Conference on Private International Law on October 26, 1960, was opened for signature on October 5,1961, and is presently in force in 28 nations. The Senate of the United States of America by its resolution ofNovember 28, 1979, gave its advice and consent to the accession of the United States to the Convention. OnDecember 27, 1979, the President of the United States approved accession. In accordance with the provisions ofthe Convention, the United States deposited its instrument of accession with the Netherlands on December 24, 1980.Upon the proclamation of the President on September 21, 1981, and publication by the Secretary of State in theTreaties and Other International Acts Series (T.I.A.S. 10072) in accordance with the provisions of title 1, UnitedStates Code, section 113, the Convention entered into force with respect to the United States on October 15, 1981. Thetext of the Convention together with its annex is appended hereto as appendix A. A list of contracting countries isappended as appendix B. [Not reproduced. See 20 I.L.M. 1409 and 1412 (1981).]

2 Administrative documents dealing directly withcommercial or customs operations, however, as well as documents executed by diplomatic or consular agents, arespecifically excluded from application of the Convention. (Conv., art. 1.)

3 Cf. French “apostiller.,” to annotate, to endorse.

4 The apostille, the exemplar for which is annexedto the Convention (.see appendix, post), may be placed on the document itself as with a stamp or on an allonge, a separatepiece of paper attached to the document“! I Conv., art. 4; cf. Fr. “allonger,” to lengthen, to extendT) While anapostille may be drawn in the official language of the issuing authority, and while its standard terms may also bein a second language--presumably the language where the document being authenticated is to be used (Amram, 60Am.Bar.Assn.J., supra, at p. 312)--its title, “Apostille (Convention de la Haye du 5 octobre 1961),” must be inFrench (Conv., art. 4), the prevailing language of the Convention's text. (Id., subscription.) The provision fora uniform format and French title was intended to facilitate identification of the apostille. (Comment, “The UnitedStates and The Hague Convention Abolishing The Requirement Of Legalization For Foreign Public Documents,” 11Harv.Internat.L.J. 476, 479 (1970).)

5 Pursuant to article 6, each contracting countryundertakes to designate by reference to their official function the authorities who are competent to issueapostilles. The designation is flexible and accommodates national peculiarities such as a federal system. (SeeAmram, 60 Am.Bar.Assn.J., supra, at p. 314; Comment, 11 Harv.Internat.L.J., supra, at pp. 486-489 $ 489, fn. 74.)The California Secretary of State or any assistant or deputy secretary of state have been designated competent to issueapostilles in California. Also designated in this state are the clerics and deputy clerks for the United States Court ofAppeals for the Ninth Circuit, and for the United States District Courts.

6 In a broader sense, legalization “includes allvarieties of 'the process by which the signature or seal on a document is deemed to have been authenticated so that thedocument may thereafter be received without further proof so far as concerns signing and sealing.’ The term has beenused to refer to many different practices whose scope and probative force vary from country to country and oftenwithin the same country.” (Comment, 11 Harv.Internat.L.J., supra, at p. 477; fns. omitted.)

7 To be clear, the question of the probative forceof a document is not governed by the Convention and continues to be determined by California law. (See Comment,11 Harv. Internat.L.J., supra, at p. 487.)

8 Aposition, or authentication of a document by anapostille, was intended to be the most stringent or maximum formality required for authentication. Article 3 providesthat even it may be simplified or abolished (waived) by unilateral, bilateral or multilateral action. (See also,Amram, 60 Am.Bar.Assn.J., supra, at p. 311; Comment, 11 Harv.Internat.L.J., supra, at p. 480.)

9 The Convention applies, by the terms of article 1,subdivision (d), to official certifications upon private documents, such as a certificate of registration or anofficial authentication of a signature. This does not authenticate the private document itself, but only itspublic aspect.

10 Article II, section 2, clause 2 of the federalConstitution provides that the President “shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to maketreaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur … .” A convention enjoys the status of a treaty.(United States v. Pink (1942) 315 U.S. 203, 230; Dr. Ing H.c.h. Porsche A.G. v. Superior Court (1981) 123 Cal.App.aa755, 758, fn. l.)

11 The Court further noted that the reason treatieswere not limited to those made in “pursuance” of the Constitution, as in the case of the laws of the UnitedStates (see art. VI, cl. 2, supra), was so that agreements made by the United States under the Articles ofConfederation, including the important peace treaties which concluded the Revolutionary War, would remain in effect.(Id., at 16-17.)

12 It is acknowledged that the state will have tomaintain two sets of rules on authentication of documents: that of the apostille in respect to public documentsemanating from parties to the Convention, and the current provisions of Civil Code section 1183 with respect todocuments from other nations. This is no different from the burden on federal courts. (See Fed. Rules Civ.Proc, rule44, 28 U.S.C.A.) Further, as has been observed, “In view of the simplicity of the apostille this “Would seem to be nosignificant burden.” (Comment, 11 Harv.Internat.L.J., supra, at p. 487.)