Article contents

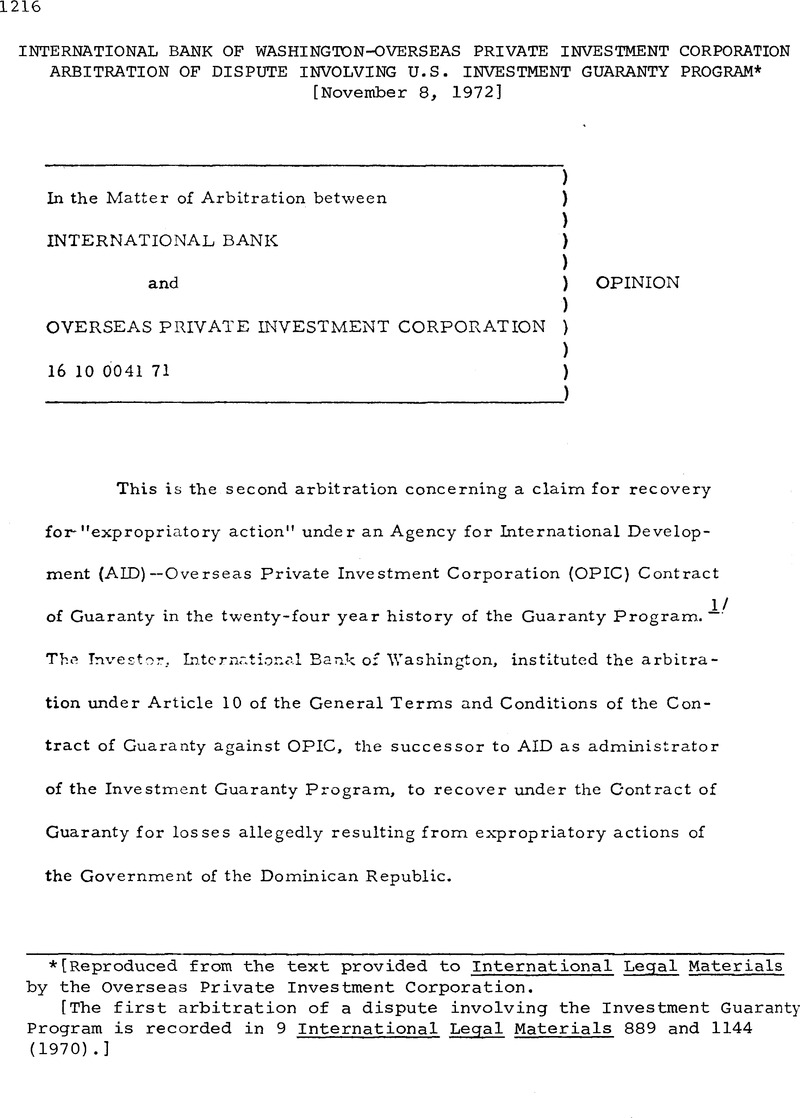

International Bank of Washington-Overseas Private Investment Corporate Arbitration of Dispute Involving U.S. Investment Guaranty Program

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1972

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.

[The first arbitration of a dispute involving the Investment Guaranty Program is recorded in 9 International Legal Materials 889 and 1144 (1970).]

References

1 The first arbitration between an investor and the Agency for International Development in a dispute involving the Investment Guaranty Program is In the Matter of the Arbitration Between Valentine Petroleum & Chemical Corporation and Agency for International Development. The Opinion in this Arbitration is reprinted in 9 Int’l. Leg. Mat. 889 (1970) (Opinion dated September 15, 1967).

2 EXPLOMA requested the following assurance on January 15, 1969: In effect, EXPLOMA requests assurances that it will be permitted to conduct its operations involving the cutting and milling of timber of the almacigo variety, pursuant to the attached contracts, for the period such contracts remain in force, including extensions thereof, or if such contracts are in force twenty years-from the date of such assurances, for a period of at least twenty years; that it will be permitted to sell the same in the Dominican Republic or export the same from the Dominican Republic during such period; that it will be permitted to do and perform such other actions as are reasonably incident to the foregoing; and that all of the above will be permitted without interruption or the imposition of unreasonable requirements. (Exhibit 27.)

3 The Special and General Terms and Conditions applicable to this case are those of AID forms 221 K ST 11-65 and 221 K GT 11-65.

On May 26, 1967, three Investment Guaranty Contracts -- providing coverage against the specific risks of currency inconvertibility, war damage, and expropriation -- were issued by AID with respect to the EXPLOMA project. One of these contracts (No. 5792) was issued to a company called COGENSA (a subsidiary of the International Bank) with respect to its initial equity investment in the project in the face amount of $40, 000. A second contract (No. 5733) was issued to the International Bank to cover loans which had previously been made to EXPLOMA in the total face amount of approximately $8 5, 000. A third contract, on which no claim has been asserted, was issued to a minority stockholder in EXPLOMA, Mr. Thomas Quick, for an equity investment of $10, 000 and for an additional debt investment of approximately $5, 000. (Testimony of Mr. Quick, Tr. , pp. 331-32.) On May 22, 1968, the International Bank received another investment Guaranty Contract covering loans of $150, 000 which had been made to EXPLOMA since January of 1967. (Respondent’s brief, p. 11, n. 4, and pp. 13-14.)

No question has been raised in this case as to whether the terms of the General Contract of Guaranty exceeded the statutory authorization for the Guaranty Program. Even if they had it would seem that AID/OPIC should be estopped from asserting the invalidity of their own contracts.

4 Section I. 15 provides:

Expropriatory Action. The term “Expropriatory Action” means any action which is taken, authorized, ratified or condoned by the Government of the Project Country, (1) commencing during the Guaranty Period, with or without compensation therefor, (2) and which for a period of one year (directly) results in preventing:

(a) the Investor from receiving payment when due in the currency specified of the principal amounts of or the interest on debt securities, or amounts, if any, which the Foreign Enterprise owes the Investor in connection with the securities; or

(b) the Investor from effectively exercising its fundamental rights with respect to the Foreign Enterprise either as shareholder or as creditor, as the case may be, acquired as a result of the Investment; or

(c) the Investor from disposing of the Securities or any rights accruing therefrom; or

(d) the Foreign Enterprise from exercising effective control over the use or disposition of a substantial portion of its property or from constructing the Project or operating the same; or

(e) the Investor from repatriating amounts received in respect of the Securities as Investment Earnings or Return of Capital, which action commences within the eighteen (18) months immediately succeeding such receipt;

provided, however, that any action which would be considered to be an Expropriatory Action if it were to continue to have any of the effects described above for one year may be considered to be an Expropriatory Action at an earlier time if AID should determine that such action has caused or permitted a dissipation or destruction of assets of the Foreign Enterprise substantially impairing the value of the Foreign Enterprise as a going concern.

Not withstanding the foregoing, no such action shall be deemed an Expropriatory Action if it occurs, or continues in effect during the aforesaid period, as a result of:

(1) any law, decree, regulation, or administrative action of the Government of the Project Country which is (a) not by its express terms for the purpose of nationalization, confiscation, or expropriation (including but not limited to intervention, condemnation, or other taking), (b) is reasonably related to constitutionally sanctioned governmental objectives, (c) is not arbitrary, (d) is based upon a reasonable classification of entities to which it applies, and (e) does nut violate generally accepted international law principles; or

(2) failure on the part of the Investor of the Foreign Enterprise (to the extent within the Investor’s control) to take all reasonable measures, including proceeding under then avail-able administrative and judicial procedures in the Project Country, to prevent or contest such action; or

(3) action in accordance with any agreement voluntarily made by the Investor or the Foreign Enterprise; or

(4) provocation or instigation by the Investor or the Foreign Enterprise, provided that provocation or instigation shall not be deemed to include (a) actions taken in compliance with a specific request of the Government of the United States of America, or (b) any reasonable measure taken in good faith by the Investor or the Foreign Enterprise, by way of a judicial, administrative or arbitral proceeding, either in furtherance of a claim of right or to counter, defend against or respond to arbitrary or unreasonable action by the Government of the Project Country; or

(5) insolvency of or creditors’ proceedings against the Foreign Enterprise other than an insolvency or a creditors’ proceeding directly resulting from acts of the Foreign Enterprise which could have been restrained under applicable law and which the investor attempted to restrain but was prevented from so doing for a period of one year by action taken, authorized, ratified or condoned by the Government of the Project Country during the Guaranty Period.

(6) bona fide exchange control actions by the Government of the Project Country.

5 These issues include the extent to which, if at all, capitalization of pre-operating expenses and casualty and early operating losses is appropriate as developmental expense in computing losses under the Contract of Guaranty, the extent to which, if at all, a Claimant is bound by the accounting principles used in computing the balance sheet in effect on the date of expropriation, and determination of the “date of expropriation” in expropriations resulting from a series of “stop and go” regulatory action.

6 See Section 1. 15 of the General Terms and Conditions of the Con-tract of Guaranty.

7 Similarly, in assessing whether a series of “stop and go” regulatory actions constitute “expropriatory action” within the meaning of the Contract of Guaranty, it would not necessarily rule out a finding of “expropriatory action” that the first such action took place prior to the Guaranty Period. The Contract of Guaranty requires that the “expropriatory action” must commence within the Guaranty Period. Clearly this would exclude a finding of “expropriatory action” based on actions commencing after the Guaranty Period. That one such action in a series of actions occurred prior to the Guaranty Period, however, would not seem decisive if the actions during that Period otherwise meet the requirements of expropriatory action. To interpret section 1.15 otherwise would be to deprive applicants for Contracts of Guaranty of protection for losses resulting from regulatory action of the same type as any regulatory action taken against them prior to the issuance of the contract.

8 Claimant relies heavily on an opinion of the Supreme Court of the Dominican Republic, dated July 23, 1971, in support of its contention that the actions of the Dominican Government made it impossible for EXPLOMA to continue operations. The opinion, which involved EXPLOMA’s liability for payment of back wages, did contain language that the lower court which found liability for back wages should have weighed:

... the situation in which the timber companies of this country find themselves at present as an unquestionable consequence of the paralyzation of work in all the saw-mills of the country, ordered by the National Government, which puts the companies which undertake this type of activity in the absolute impossibility to continue their work . . . . “ (Exhibit No. 4, Translation, p. 9. )

The opinion of the Supreme Court, however, merely remanded the case to the lower court and directed the lower court to “weigh” this situation. It did not find the situation conclusive. Moreover, the decree of which the Supreme Court took judicial notice was Law No. 211, enacted in November of 1967. EXPLOMA, with special government permission, operated for more than a year after the enactment of this law. and apparently the Dominican Labor Department specifically determined that no government action prevented EXPLOMA’s operation. (Respondent’s reply brief, pp. 12-14, nn. *.)

9 For an outline of the applicable international legal standards, see Sections 165, 166, 197 and 201 of the Restatement of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States (Second) (1965). It is the opinion of the arbitrators that the actions of the Dominican Government in this case, as applied to the cutting of Almacigo by EXPLOMA, did not amount to a “taking” requiring the payment of compensation under the standards set out in Sections 185-92 of the Restatement (Second).

- 1

- Cited by