Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 February 2019

1 While services currently account for over 60 percent of global production and employment, they represent no more than 20 per cent of total trade (BOP basis). This — seemingly modest — share should not be underestimated, however. Many services, which have long been considered genuine domestic activities, have increasingly become internationally mobile. This trend is likely to continue, owing to the introduction of new transmission technologies (e.g. electronic banking, tele-health or tele-education services), the opening up in many countries of long-entrenched monopolies (e.g. voice telephony and postal services), and regulatory reforms in hitherto tightly regulated sectors such as transport. Combined with changing consumer preferences, such technical and regulatory innovations have enhanced the “tradability” of services and, thus, created a need for multilateral disciplines.Google Scholar

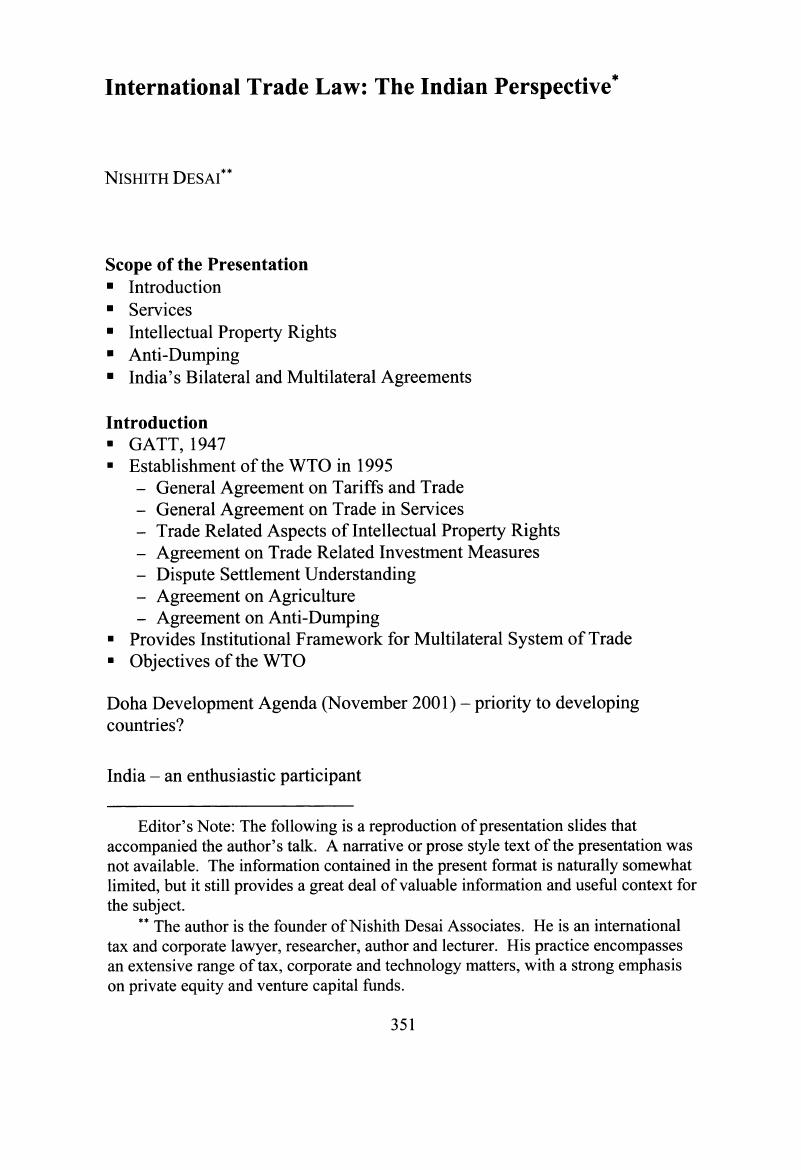

The creation of the GATS was one of the landmark achievements of the Uruguay Round, whose results entered into force in January 1995. The GATS was inspired by essentially the same objectives as its counterpart in merchandise trade, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT): creating a credible and reliable system of international trade rules; ensuring fair and equitable treatment of all participants (principle of non-discrimination); stimulating economic activity through guaranteedpolicy bindings; and promoting trade and development through progressive liberalization.Google Scholar

GATS applies to measures taken at all levels of government and by nongovernmental bodies to whom powers delegated by governments or authoritiesGoogle Scholar

It excludes services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority – services which are supplied neither on a commercial basis nor in competition with one or more service suppliersGoogle Scholar

Mode-wise classification reflects complex nature of international transactions in servicesGoogle Scholar

Brings into purview of the GATS investment, labour market, immigration policies, and wide range of domestic regulationsGoogle Scholar

Cross-border supply is defined to cover services flows from the territory of one Member into the territory of another Member (e.g. banking or architectural services transmitted via telecommunications or mail);Google Scholar

Consumption abroad refers to situations where a service consumer (e.g. tourist or patient) moves into another Member's territory to obtain a service;Google Scholar

Commercial presence implies that a service supplier of one Member establishes a territorial presence, including through ownership or lease of premises, in another Member's territory to provide a service (e.g. domestic subsidiaries of foreign insurance companies or hotel chains); andGoogle Scholar

Presence of natural persons consists of persons of one Member entering the territory of another Member to supply a service (e.g. accountants, doctors or teachers). The Annex on Movement of Natural Persons specifies, however, that Members remain free to operate measures regarding citizenship, residence or access to the employment market on a permanent basis.Google Scholar

The supply of many services is possible only through the simultaneous physical presence of both producer and consumer. There are thus many instances in which, in order to be commercially meaningful, trade commitments must extend to cross-border movements of the consumer, the establishment of a commercial presence within a market, or the temporary movement of the service provider himself.Google Scholar

2 New commitments include, inter alia, air transport services; architectural, integrated engineering and urban planning and landscape services; construction and related engineering services; distribution services; educational services; environmental services; life insurance services and services auxiliary to insurance; recreational, cultural and sporting services; tourism services; and veterinary services.Google Scholar

Improvements to existing commitments include asset management services and other non-banking financial services; banking services; computer and related services; construction and related engineering services; engineering services; research and development services; basic telecommunications and value-added telecommunications services.Google Scholar

3 The Parliament passed the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act in 2001. Criteria for the registration of new plant varieties include novelty, distinctiveness, uniformity, and stability. Applications must be made to the Registrar-General of Plant Varieties; applications that comply with the requirements of the Act, are advertised. Opposition to the registration must be made within three months of advertisement; the applicant has two months to respond. If there is no opposition, or if the opposition is rejected, the variety is registered in the Plant Varieties Registry and an official certificate given to the applicant. For registration of essentially derived varieties, the Registrar must forward the application and supporting documents to the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority for examination. If the Authority is satisfied that the essentially derived variety has been derived from the initial variety, it directs the Registrar to register the new variety.Google Scholar

The variety is novel if, at the date of filing, the propagating or harvested material has not been sold or otherwise disposed of by or with the consent of its breeder for exploitation in India, earlier than one year before the date of filing of the application, or, outside India, earlier than six years for trees and vines and earlier than four years for other varieties.Google Scholar

The term of protection is nine years for trees and vines and six years for other crops, renewable for a further nine years (for extant varieties of trees and vines, or a total of 15 years for annual crops from the date of notification under the Seeds Act 1966). However, under Chapter VI of the Act, a farmer is entitled to save, use, sow, re-sow, exchange, share or sell his farm produce, including seed (except branded seed), of a variety protected by the Act.Google Scholar

The Act also provides for benefit sharing.Google Scholar

•The Semiconductor Integrated Circuits Layout-Design Act was passed in September 2000. There have been no changes to this legislation since the previous Review. Applications should be made in writing to the Registrar and filed at the office of the Semiconductors Integrated Circuits Layout-Design Registry, although it appears that the Registry is not yet functional.Google Scholar

Infringement is defined as unauthorized reproduction, whether by incorporating in a semiconductor integrated circuit or otherwise, a registered layout-design or any part of it, or unauthorized import, sale, or distribution for commercial purposes of a registered layout-design or a semiconductor integrated circuit incorporating a semiconductor integrated circuit with a registered layout-design. However, reproduction is permitted for scientific evaluation, analysis, research or teaching. In addition, if a person creates another original layout-design on the basis of scientific evaluation or analysis of a registered layout-design, that person has the right to reproduce, sell or incorporate this layout-design in a semiconductor, while if a person independently develops a layout-design that is identical to a registered one, that person may use it as desired without infringingGoogle Scholar