Introduction

The Covid-19 crisis has taken the entire global community into a rude surprise; in an astonishingly short period, it has engulfed the entire world, with several deaths and complete breakdown of normal course of life, resulting into untold human miseries. In addition, every strategy that has been adopted seems inadequate to handle the situation. Even the highest global body of health governance, the World Health Organisation (WHO), has expressed its inability to comprehend the nature of the disease which seems to acquire newer forms from time to time.

“Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus”; it creates respiratory problems, particularly affecting elderly people and those with “medical problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer are more likely to develop serious illness” (WHO 2020a). WHO's China office reported on 31 December 2019 that forty-four people in China's Wuhan province have been affected by coronavirus. By mid-January, it has spread into neighbouring countries like Thailand, Japan and Korea. In addition to increased medical research, WHO recommended surveillance for continuous monitoring on health issues (WHO 2020b). By early March, WHO confessed of being in an “unchartered territory” and diagnosed containment as “the top priority for all countries” (WHO 2020c). The Director-General remarked: “With early, aggressive measures, countries can stop transmission and save lives”; emphasising “to break the chains of transmission and contain its spread” with comprehensive “all-of-government and all-of-society approach,” than merely “the health ministry” alone; and lamented the lack of “strong political will” in some countries (WHO 2020d; emphases added); and observed subsequently, “the threat of a pandemic has become very real” (WHO 2020e). On its “Situation Reports” from time to time, WHO continued to emphasise on governmental action and strong leadership to mobilise society's efforts against Covid-19; thus necessitating sound governance for meeting the challenge of Covid-19 pandemic.

In traditional sense, governance is “about execution…the performance of agents in carrying out the wishes of principals”; there is no evidence that democracy and governance are “mutually supportive”; non-democratic regimes may also have better performances in governance (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2013, pp. 350–51). However, since the 1990s, particularly in developing countries, it was realised that democracy, rather than repression, is a prudent way to govern, because of the growing demands for human rights from below, and pressures by large population for both poverty-alleviation and environmental protection (Fisher Reference Fisher1998). As supportive condition to development, democracy emerged as an indispensable agenda of governance to check the arbitrary use of political power, through rule of law, human rights, and accountable and transparent administration (Smith Reference Smith2007, pp. 4–6).

In recent times however, democracies across the world are facing crisis, particularly marked by government's attack on media, civil society; the opposition; and even the electoral process is now being tampered with by powerful groups. India has ranked among the “autocratizing countries,” experiencing an overall decline in democracy between 2009 and 2019. However, the year of 2019 has also witnessed significant pro-democracy mobilisations (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Lührmann, Hellmeier, Grahn and Lindberg2020). Under pandemic situations, many places around the world have witnessed the escalation of state's repressive power, such as excessive police violence, particularly while enforcing lockdowns; subversion of electoral process; targeting opposition; and drastically curtailing press freedom. Alongside, minorities were targeted in many countries including India; digital surveillance misused to encroach upon individual privacy and freedom; and corruption increased in the public sector. Yet, there had also been sustained endeavours in many parts to reclaim the democratic space in a variety of ways known as “democratic pushback”; CSOs have taken initiatives to supplement state capacities by distributing medicines and relief to affected people; launched sustained counter-attacks against disinformation; coordinated with WHO guidelines on health updates and disseminated correct information via social media. The opposition monitored government's performances on handling the pandemic, through oversight (Youngs and Panchulidze Reference Youngs and Panchulidze2020).

Worldwide, Covid-19 has thus unlocked the ongoing intra-regime tensions between democratic and anti-democratic tendencies into open. Contemporary Indian politics presents an appropriate example; the ruling elites' preference for one-way communication creates significant stress on democratic governance. We shall first briefly survey India's socio-political history since independence, for understanding the context of government's strategies on Covid-19 pandemic. In the second section, using primary sources extensively, we shall study the application-part of governance: policy-communication – the process through which various policy-decisions on managing the pandemic and welfare-schemes was communicated from state to society via government, with qualitative content analysis of the Prime Minister's speeches at various phases of the pandemic. Alongside, through analysis of the posts appearing on popular Facebook groups during this period, we shall identify the social context of policy-communication in the diversity of public opinion around Covid-19. Finally, we shall reflect on accountability; it adds the “democracy” dimension to governance. During this period, behind explicit policy-communication, many contentious policies and decisions have bypassed the usual democratic channels, despite their significant impact upon democratic process and the overall well-being of people. A few recent issues will be studied for their implications on democratic governance. Overall, given that Covid-19 pandemic is ongoing, and continuously unfolding into newer dimensions, we shall refer to various government notifications and media reports from time to time.

Politics in India: an overview

An observer commented that India is “the most heterogeneous and complex society on earth” (Manor Reference Manor1996, p. 459). Alongside six major religions: Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, Buddhism and Jainism; 22 languages are recognised in the constitution (Ministry of Education 2013; Religion 2001). The density of India's population is available on Table 1. In India's federal structure, power is distributed between central and state (provincial) governments; regions directly administered by central government are known as Union Territories (UT).

Table 1. Population of India

a “Provisional Population Totals” (2011) Retrieved 7 July 2020 (https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/india/final_ppt_2011_chapter3.pdf).

b (Census 2011).

c NCT – National Capital Territory.

d Became Union Territory in 2019.

Political history since independence

India gained independence from the British rule on 15 August 1947; the founding leadership drafted a democratic and inclusive constitution. The Indian National Congress (INC), which spearheaded the movement of independence, had governed India for the first thirty years. However, since the 1990s, Indian politics became extremely competitive, and unstable coalition governments became the norm. In 1999, the coalition National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was able to complete its full term – the first-ever non-Congress formation. It was defeated at the subsequent 2004 polls and another coalition the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), led by India's longest ruling party the INC, came to power; and returned to power in the subsequent 2009 polls as well. Throughout this period, incumbent governments had difficulties in managing coalitions, at times affecting the process of governance.

The underlying changes at social levels since the 1980s have resulted into decisive shift in Indian politics in 1990s; Yadav and Palshikar articulate them as “three Ms”: Mandal, Mandir and Market. Mandal signifies the rise of socio-economically backward castes and dalits (the oppressed, lying at the bottom of social pyramid) in Indian politics as a social force with formidable electoral clout. Mandir or temple indicates the deep polarisation between Hindus and Muslims, having significant effect on electoral politics. Finally, market refers to the definite shift in economy from state-directed to market-led paradigm, starting decisively with the liberalisation programme of 1991 (Yadav and Palshikar Reference Yadav, Palshikar, de Souza and Sridharan2006).

The UPA government, during its 2009–2014 tenure, earned the term “policy paralysis” for its often-visible inability to authorise decisions firmly (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2016, pp. 550–52). The democratic space has expanded with coalition politics, as reflected in the assertive roles of judiciary, Election Commission, and enactment of many progressive social policies, such as the rights to information, education and food; yet, the instability of government has led to many crises. The media continuously advocated for a strong government at the Centre. In 2014, the coalition NDA was elected to power; the chief coalition partner BJP, under the leadership of Narendra Modi, was in a position to singularly form a government, securing 282 seats out of the total 544 in Lok Sabha (the House of People), which is the lower house of Samshad – India's Parliament. Thus, thirty years after 1984, a single party secured an absolute majority of its own. The same coalition returned to power with increased support in the general elections of May 2019. BJP alone secured 303 seats of the total 544; its share of vote increased from 31% in 2014 to 38.37% in 2019. The second best performer, INC secured fifty-two seats with 19.55% of votes (Lok Sabha Election Results 2019).

Despite severe problems of poverty, violence and recurring threats to national unity, democracy continues in India. Kothari claims India as a concept of cultural entity since ancient times, with mutual accommodation and exchanges in a diverse setting. Subsequently, freedom struggle, based on mass mobilisation, values of liberalism, non-violence and accommodation of diversities, worked as foundation for democracy in India (Kothari Reference Kothari1988). Later day writings reinforced this thesis; the “complex social divisions in India,” in the lines of caste, class, religion, region and language, do not threaten democracy, rather “prevent tension and conflict from building up along a single fault-line” (Manor Reference Manor1996, pp. 463–64). These divisions have actually strengthened civil society's efforts towards democratisation (Oommen Reference Oommen and Jayaram2005). In addition, after independence, the leadership has taken immediate well-planned measures to restrict the army's role under democratically-constituted civilian control. In the turbulent 1970s, Indian military has shown considerable grace and sagacity of avoiding involvement into domestic politics, despite many provocations from both the government and opposition (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017).

Political ideologies and practices

India is a multi-party democracy; in 2019 elections alone, 672 parties have contested, including “independent” candidates (ECI, 2019) formally affiliated with no party. However, at the time of India's independence, two major political formations opposed the ruling Congress Party: the Hindu right and the leftist block – then undivided Communist Party of India (CPI) being the most prominent among them. Later on, the Congress hegemony on Indian politics was challenged and many changes occurred, as mentioned above, but the main ideological matrix more or less remains the same – the Congress is a “catch-all” party with centrist dimensions. In many parts of India, political parties based on the support of historically deprived sections of people, dalits and the tribals, have emerged. Their main agenda is social justice for socio-economically excluded and backward castes; politically, they generally assume centre-left positions.

BJP has a Hindu-majoritarian ideology and adopts confrontational posture at times for consolidating support base. It believes in neoliberal capitalism and prefers strong relationship between India and the United States (US/USA). The parliamentary Left is overwhelmingly led by CPI(M) – the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which is the major partner of the present ruling Left Front in Kerala; and the ones in West Bengal (1977–2011) and Tripura (1993–2018). CPI(M) strongly believes on welfare state; favours good relation with socialist countries; and a bitter critic of Western, particularly the US imperialism. As Wood (Reference Wood1965) records, the radical section in undivided CPI supported China during the Sino-Indian war of 1962 and later on formed the CPI(M) in 1964.

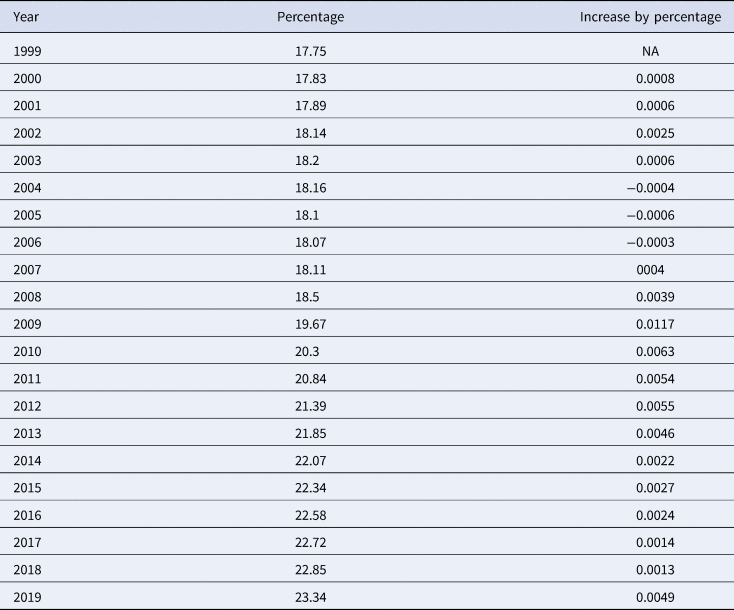

Despite plurality of political ideologies and keen electoral competitions, India fares poorly on poverty eradication and human development. In 2015, 23.88% of the world's extremely poor people lived in India (World Bank 2019), and ranked 129 in the Human Development Index among 189 countries in 2019 (UNDP 2019). In fact, formal democracy seems to have little effect on reducing abject poverty and deprivations, because elites from all political parties have a de facto consensus on economic policies (Kohli Reference Kohli2012). Yet, by the end of 2019, many serious problems started knocking loudly. The rate of youth unemployment has risen sharply, touching an all-time high since 1999 (see Table 2). During this period, the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and National Register of Citizens (NRC) Bills were introduced, posing threats to existing inclusive and pluralist notions of citizenship (Jayal Reference Jayal2019, pp. 34–35). Protest movements opposing their subsequent enactment had continued till the time of complete lockdown.

Table 2. Youth unemployment statistics in India

Statista (2020) “India: Youth unemployment rate from 1999 to 2019” Retrieved 13 July 2020 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/812106/youth-unemployment-rate-in-india/). The calculation on “increase,” on the right-most column, is mine, on the basis of comparison to previous year.

Even during normal times, this government has taken many unpopular decisions; most notably, the demonetisation of Indian currency in November 2016. Yet, not much public outrage against that move was visible; probably, people had confidence on the government's promises on eradicating the huge amount of unaccounted (“black”) money and corruption. Whereas at times, unpopular and strong decision-making becomes necessary for governance, extreme care must be adopted to ensure that it does not permanently jeopardise the democratic process. Since early 2020, the Indian state, like governments elsewhere, faced the unprecedented and continuing challenge of Covid-19 pandemic. The way Indian government handled the pandemic and made many contentious decisions in the context of Covid-19 presents an interesting case for democratic governance.

State, society and policy-communication on Covid-19

State is the supreme embodiment of power-relations in society, but for success of its programmes and activities, it has to depend on various social forces, through which its powers are exercised (Jessop Reference Jessop and Adrian1990). Public policies are courses and principles of informed action by government and other powerful actors in society, disseminated in the name of people. Policy communication is essentially concerned with managing the information flow. Communication is a “mover” in the process of governance, for its capacity to “construct” reality (Sinha Reference Sinha2018, pp. 41–49). For effective implementation and achieving desired results, policy-makers must involve people by means of persuasion, rather than relying upon repression. Given the existence of various social forces, persuasion often leads to deliberation. Yet, there are constraints to arrive at timely decisions, based on the available information (Goodin, Rein and Moran Reference Goodin, Rein, Moran, Michael Moran, Rein and Goodin2006). Communication plays major roles in implementing policies that have been formulated, as evident in the contexts that have motivated decision-makers to formulate certain policies, and the way such policies were taken to society. Information is a crucial factor, because it enables policy-makers justify decisions to their advantage, through the process of communication. Governance is inevitably linked with communication of policies.

The most significant policy-decision by government on Covid-19 was announcing and implementing the lockdown – complete shutdown of all-but-bare-essential activities. It started with a one-day shutdown on 19 March 2020, known as “Janata Curfew,” followed by several rounds of lockdown, starting from 25 March 2020. On 24 March 2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs designated Covid-19 epidemic as a “disaster” (MHA Order 2020), and issued a six-page circular suspending much of the services, including public transportation, and prohibiting all socio-cultural activities, including religious gatherings. Most notably, stringent penal provisions, as outlined in the “Disaster Management Act 2005,” were mentioned in detail, occupying the last three pages of the circular (MHA Guidelines 2020). In other words, the possibilities of repressive measures were indicated. During this period, the state machineries were mobilised on full scale. In various Indian languages, the catchword “stay home, stay safe” had reverberated on media and cellphone caller tunes; citizens were exhorted upon to observe lockdown and related health guidelines strictly. Police pickets were installed in every public place such as markets, announcing the lockdown rules again and again.

Government and policy communication

The most visible governmental response to the pandemic was imposing lockdown that proceeded along two tracks: one, the Prime Minister's highly publicised addresses to nation through Mann ki Baat (Words of Mind)Footnote 1 programme; two, various governmental notifications on the implementations of lockdown, starting within four-hours. Broadly, the Prime Minister's several speeches to the nation, from 19 March to 30 June 2020, may be classified into three categories: emotion-filled personalised appeals, patriotic overtones and propagation of welfare policies.

In his speech on 19 March 2020, the Prime Minister started with “gratitude” that people of India have always honoured his “requests” with blessings. Outlining the menace of global pandemic, he mentioned all sections of people in India, the rich, poor and middle class, and emphasised upon observing a day-long “Janata Curfew” (“Curfew by people, of people and for people” – translation mine, from Hindi) on 22 March 2020. He again “requested” people to cheer up with clapping, ringing bells or dining plates in the afternoon at 5 PM as a mark of appreciation for people who are tirelessly working for months in airports, hospitals and street. The speech thus became famous for day-long people's curfew and ringing the plates. Meanwhile, another point he made at the end of the speech went virtually unnoticed: we may have to wait more to overcome the pandemic (Janata Curfew Speech 2020). On the evening of 24 March 2020, while announcing the lockdown for the next 21 days, he continued to sketch the frightening scenario of the global pandemic, particularly emphasised upon maintaining social distancing, and with folded hands, “requested” people to stay indoors to break the cycle of coronavirus from spreading: “I tell these things not as Prime Minister, but as a member of your family: stay at home; stay at home; and do only one thing: stay at home” (translation mine, from Hindi) (Lockdown-1 Speech 2020a).

However, the seriousness of the issue got somewhat diluted by the next speech on 3 April, when he weaved a mystical atmosphere and asked people to switch off electrical lights on 5 April at 9 PM for nine minutes and light a candle, lamp, torch to ward off the “darkness” and evil – this is known as “diya jwalao” speech (“light the lamp” – translation mine, from Hindi) (Diya Jwalao speech 2020). When people observed the “tasks” he desired, bell-ringing and lighting, media documented the flagrant violation of health-security norms. While announcing the extension of lockdown on 14 April, the Prime Minister started with paying homage to the birthday of Dr B. R. Ambedkar, the maker of Indian Constitution and icon of dalit movement fighting for social justice. At the same time, he mentioned the major festivals during that period. Thus, after touching the emotional chord of majority of Indians, he justified the “timely” imposition of lockdown saying that despite its economic costs, “compared to the lives of Indians, it is nothing” (translation mine, from Hindi; Lockdown-2 Speech, 2020b); it has saved many lives (Unlock-2 Speech 2020b).

The second feature of Prime Minister's speech was fiddling with patriotism, with frequent references to war against the pandemic, and the need for unity and strength of 1300 million people. In the beginning, alongside mobilising various organs and departments of the state at every conceivable level, he sought to involve the broad range of civil society such as social, religious and other voluntary organisations, as well as students' service learning departments such as National Cadet Corps (NCC) and National Service Scheme (NSS) in the “battle” against corona; he also reminded the tireless efforts of various government functionaries such as hospitals, police force, drivers, cleaners and the daily wage-earners from unorganised sectors. “Janata Curfew” has been projected as a show of solidarity, unity and strength (Janata Curfew Speech 2020), popularly designated as “corona warriors.” This tone got synchronised with his party's fundamental ideological orientation, particularly in the context of escalation of Sino-Indian border conflict during this period.

Patriotism presupposes state's strong authority. The Prime Minister lamented that in many cases, people have attacked police (Lockdown-1 Speech 2020a); and issued subtle warning repeatedly against people violating lockdown rules. He urged people not to be careless, nor allowing anybody to be careless (Lockdown-2 Speech 2020b), and people who violate the health-security norms need to be opposed, stopped and persuaded (Unlock-2 Speech 2020b). The necessity of strong authority has been felt at times, when medical workers in many parts of the country faced “stigmatization and ostracization,” physical violence and damages to their property. In an Ordinance of 22 April 2020, the government clearly elaborated severe penalties: high-volume fines, long-term prison sentences and speedy trial for offenders (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2020). However, it might have also created the framework for a tacit approval of police violence, as reflected on a section of social media.

The third feature of Prime Minister's speech is propagating various welfare schemes undertaken by the government since its takeover. From the beginning, he assured about the steady supply of daily necessities and medicine. Subsequently, he mentioned the new guidelines “Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana” (PMGKY; the “Prime Minister's Relief Plan for Poor” – translation mine, from Hindi). The most spectacular announcement was “Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan” (“Campaign for Self-reliant India” – translation mine, from Hindi); although presented as a relief package, it was essentially a major economic policy, following the lines of the projects of this government over last few years: “Make in India” (for self-sufficiency in manufacturing sector); revamping the cottage, medium and small-scale enterprises; tax reforms for attracting investments in agriculture and business (Atmanirbhar Speech 2020). In subsequent speeches too, he mentioned about various efforts by the central government to ameliorate the problems of people: running “Shramik” (workers’) special trains; quelling the locust problem; massive healthcare provisions; the way poor people benefitted from PMGKY schemes; and free delivery of food through PDS – the Public Distribution Systems (Unlock-1 Speech 2020a; Unlock-2 Speech 2020b). However, despite such propaganda, a small fraction of people have actually benefitted from them; in April, 200 million people were left out of the PMGKY scheme, and though the Prime Minister announced allocating about 10% of India's GDP for the poor in his “Atmanirbhar Speech,” the real figure turned out to be lesser than 2% (Harriss Reference Harriss2020, pp. 615–17).

Critics argue that had the government taken the country's medical research institutes and epidemiologists into confidence, and taken timely action in February, the imposition of lockdown and consequent hardships could be avoided (Priya et al. Reference Priya, Acharya, Baru, Bajpai, Bisht, Ghodajkar, Guite and Reddy2020). The Prime Minister's speech, Mann ki Baat, has long been criticised as a one-way communication. Despite the government's justification on the timeliness of lockdown, some problems are too glaring to ignore. Since the beginning, the Prime Minister sensed severe hardships of the country's poor and lower middle class, and appealed the business and upper middle people not to deduct salary/wages of the people who serve them: “take decisions based on humanism and empathy” (translation mine, from Hindi; Janata Curfew Speech 2020). On 12 May, he reiterated the severe hardships faced by working class people (Atmanirbhar Speech 2020). It appears that the government has relied overwhelmingly on goodwill and voluntarism, instead of concrete policies. Subsequently, he also expressed intentions about setting up “Migration Commission” (Unlock-2 Speech 2020b); by this time however, a crisis of severe magnitude has erupted in many parts of India.

Social media's reflections on Covid-19

Media probably reflects public opinion more appropriately than the political leadership. It is true that the ruling coalition led by BJP performed extremely well in the 2019 elections, but media and voting behaviour do not always concur, for several reasons. First, voting occurs once in a few years, whereas media is concerned with everyday life. Secondly, strong commitment to a particular political party or ideology can be found among very few people; it does not apply to much of the population with various interests, which may appear inconsistent with the usually coherent programmes and policies of political parties. One vote is too inadequate to reflect our all preferences. Media, on the other hand, is a broad canvas, where different shades of opinion do surface from time to time. It is more visible in social media – a significant forum of common people, many of whom do not have particular political agenda or sharp ideological orientations. They react/reflect from their instant impulses – likes or dislikes, approval or disapproval to particular events, incidents or phenomena. As a result, social media is an indicator of the diversity of society's opinion, which does not necessarily follow structured patterns.

Since 2011, a trend has been observed in India, “corporatisation of the media”; with the global recession, the source of media's finance, advertisement revenue, was drying up, leading to massive “mergers and acquisitions” that resulted into near-monopoly control over media (Guha Thakurta and Chaturvedi Reference Guha Thakurta and Chaturvedi2012, pp. 10–11). In recent times, the credibility of Indian media has been seriously affected. A survey of 180 countries finds India at the 142nd position (World Press Freedom Ranking 2020) – the worrisome bottom-most quarter; and certainly embarrassing for a country known to be the world's largest democracy. In common parlance, a section of mainstream media is now derisively termed as “godi” (lapdog) media, for its apparent pro-government leanings.

In social media however, people are not passive receivers and consumers of information; it is rather a two-way communication; therefore quite participatory by nature (Sinha Reference Sinha2018). In 2010–2011, social media has played instrumental roles in the spread of pro-democracy movements in the Arab world (Smidi and Shahin Reference Smidi and Shahin2017, p. 204; Tudoroiu Reference Tudoroiu2014). Yet, anti-democratic forces are also capable of using social media. “The same technology that can mobilize large numbers of demonstrators might also be used to spread disinformation” (Johnston Reference Johnston2014, p. 112). The major social media platforms are Facebook, Youtube, Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp; Facebook is the most popular among all users. In the last three years, the government's activism on social media has increased by 150% in seventy countries including India; it used social media in various ways to harass and bully opponents and dissenting voices (Bradshaw and Howard Reference Bradshaw and Howard2019). Thus, although with a history of little more than a decade, social media has significantly impacted upon state–society relations at contemporary times. It has played a significant role in the Indian government's handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as packaging government policies during the period.

As Facebook is the most popular social media, we shall study two public groups: “Manusher Sathe Manusher Pashe” (MSMP) – in English, it means “With People, Beside People”; and “The Indian Liberals” (TIL). In each group, the phrase “corona and covid” was entered in the search box to access the posts. The volumes of discussions in these Facebook groups indicate significant public involvement on the Covid-19 issue. Whereas Table 3 gives us the summary of Covid-19-related posts in these two groups, an analysis of major posts shall enable us understanding the trend of public opinion. While discussing particular posts, instead of mentioning the names of post-authors, I shall use acronyms of their names.

Table 3. Facebook groups' response to Covid-19

The above-mentioned sites were accessed from 17 May to 31 July 2020. “Symbolic responses” include expressions of emotion available on Facebook: like, smile, sad, angry, love and affection. Such consolidated figure is presented to emphasise that message of the Post has reached people – positively or negatively.

The membership figures of MSMP have ranged between 93,326 and 93,697 people from 17 May to 31 July 2020, and Bengali is the most-communicated language here; as a result, enables participation of people without much education or familiarity with English. In the “Group Description” section, a nine-point rule is set out, prohibiting false news/information, vulgar/abusive words, personal attacks, and attacks on any leader or party symbols. The group administration of eight is claimed to have drawn from people supporting various political parties; they insist on appropriate links for every news item shared; clearly mention their belief in the “freedom of speech,” but not “indecency”; and insist that nobody should block any member in the Group Administration; anybody violating these rules shall be blocked “without warning.” Despite these however, the group has a “free-for-all” character; members can be seen openly trading abusive and foul languages; sharing suspicious news items and various types of vilification campaigns; personal attacks and like. Yet despite these, informed opinions and debate can be found on many posts.

A post (AC) squarely blames China for the spread of coronavirus. It draws 107 comments, many of them are slanging match; supporters and opponents tell each other as agents of China and the USA. However, informed debates are also found; a left supporter claims the virus is a result of natural mutation, but such an anti-China hype is created to target the leftists, for weakening their protests against anti-people policies. In reply, another member claims that the exact cause of Covid-19 is not yet confirmed; people on Chinese payroll are spreading the story of natural mutation. Both of them refer to media sources for their claims. OGM mentions poor people's plight during lockdown, leading to a debate on welfare. On 19 April, to ridicule the Hindu nationalists, he uses the adjective “traitor” to a student of Aligarh Muslim University who invented an affordable Covid-19 testing kit. Earlier, on a different post, NG blamed the Muslim religious organisation, Tablighi Jamaat, for flouting the social distancing norms and spreading Covid-19, by organising programmes during the lockdown. HD, a left supporter, posted some photos of Hindu nationalist leaders and termed them as “traitors”; most of the 169 comments draw strong reactions against Marx, Muslim and China, as well as debates on secularism.

Yet another post sharing newspaper links strongly condemns the irresponsible behaviour of powerful people; a young man studying in a British University, despite having tested Covid-19 positive, has indiscriminately socialised and travelled across the city of Kolkata. He is from an educated and influential family – mother a top bureaucrat and father a child-specialist. Three people join the author to condemn the behaviour. Several other posts laud Modi for his leadership or informing about strong penal provisions against those obstructing “corona warriors” – people on the forefront of the battle against the pandemic. In fact, several cases have been reported where doctors, nurses, police have faced hostile reaction from neighbours, for their having contact with Covid-19 patients. PP imagines a doomsday “92 days after lockdown,” no food is available, no place in hospital, electricity is mostly unavailable – these happen because initially people took the lockdown casually. PP concludes, “The incidents above are fictitious; but if you do not want to see this happen, follow the governments’ orders meticulously” (translation mine, from Bengali).

The other group “The Indian Liberals” (TIL) describes itself as a “meeting ground where we will strive to create an atmosphere in which people will feel free to express all and any of their viewpoints” – open to people from all nationalities and faiths, as well as the believers and non-believers of religion. People facing any offensive comments are advised to report to administrators, consisting of five persons. Generally, the group is critical to the government of India; foul words are rarely used, and well-informed but somewhat one-sided discussions, rather than debates, occur. Usually, people who differ, unless well-informed, face severe contestations and condemnation at times; this does not usually happen to people supporting the group's line of thinking, despite sharing suspicious posts. The medium of communication is almost entirely in English; between 17 May and 31 July 2020, its membership figures ranged between 55,755 and 56,026 people.

SR shares a news link ridiculing a Hindu spiritual leader who claims herbal treatment against Covid-19. Everybody supports him in varying degrees: two of them use slangs, and others heap adjectives such as “fraud,” “idiot” and “laughing stock” to the spiritual leader; pertinently, herbal cure is often seen as a pet project of the present government. However, one comment takes a balanced view, saying herbal medicines have merits, but must not go to wrong hands. VN informs about plasma donated by Muslims, as therapy for Covid-19. HT acknowledges the merits of lockdown, but also points out its adverse effects on the livelihood of poor people. SS again doubts the prudence of lockdown, particularly its adverse effects on the economy. He also debunks false propaganda against Tablighi Jamaat. BA coins the term “covidiots” who spread superstition, hatred and communalism on the garb of fighting Covid-19. On the caption “Ahmedabad, a man made disaster,” SM gives a detailed chronology on how the “Namaste (Welcome/Greetings) Trump”Footnote 2 show on 24 February 2020 has led to a sharp escalation of Covid-19 cases in Ahmedabad, despite WHO warnings by that time. Other issues include migrant workers' plights; “biased attitude” of central government and the media; unscientific requests of the Prime Minister; religious division; necessity to follow health-safety measures; and police violence. As Table 3 shows, there are large numbers of “shares” in TIL. People share others' posts for their own reasons, but the possibilities of surveillance cannot be denied.

The Facebook posts of two groups thus mirror a miniature of the wide variety of public opinion in India. The credibility of mainstream Indian media has been questioned repeatedly, but they have also published and discussed the issues; in Table 3, we find many Facebook posts that refer to news items published in mainstream media. Yet, it cannot be trusted to represent every shade of opinion; the liberal democratic ideal of media where people will mutually exchange opinions based on reason is largely elusive, because public opinion itself is often biased and partisan. In this milieu, social media provides us the key to unlock the context of policy communication.

First, the middle class is its chief consumer, whose daily life experiences are deeply entangled in interactions with people from diverse backgrounds. With mainstream and social media, they have exposure to policy-makers' views. Some of them also have access to the corridors/centres of policy-making levels. The knowledge/information they gain at that level is communicated to common people while using public transport, domestic help of various sorts, visiting markets and several public spaces. This way, they carry ideas across the society, by acting as liaison among various segments of population. There are many layers of middle-class in India, staying in big cities, smaller towns and rural areas. Many of them visit local markets for daily consumption, and thus develop human relations with the larger society.

Secondly, on social media, many people are passive participants or silent onlookers; they may not actively participate in the discussions, but silently consume the information and insights shared there. This author, for example, got clue to some issues without any active participation, which proved useful for this paper. Social media reflects popular culture; at least nominally, it allows every participant to speak on their behalf, and thus reflect a microcosm of society's opinions. Engaging into public group debates is a costly exercise and demands substantial time, often at the expense of mental peace and other works. When people support, good feeling occurs. Many people may like rational debate, provided the person himself/herself cherishes democratic values; but there are also high chances of harassments such as being dragged into irrelevant arguments, abuses and insults. For sensitive people, it may touch the weak points – the raw nerves, particularly on issues concerning sexuality or family members. It is quite a common practice to bully minority opinions contradicting the overall spirit of the post/group. Yet, many people regularly contribute to social media; and in groups like MSMP, do brave acrimonious exchanges. It is not known whether they are paid for such activism, but a public space is created; people, including political activists, are introduced to other sides of the reason which is virtually impossible in contemporary mainstream media. Through intense discussion, for or against government policies and performances, social media works as a vibrant forum for policy-communication, which makes its way through and takes place in the context of India's diversity of opinions. In addition, data evident in Table 3 also reflect people's intensive involvement with pandemic-related issues.

In recent times, democracy in India has been “marked by intense hostility and zero tolerance of alternative opinions. Crass populism, rhetoric, dramatics, vilification, ridicule, and personal attacks” are practiced by both ruling and opposition parties, as well as media and CSO representatives (Sinha Reference Sinha2020, p. 4). In this context, the leadership may, on one hand, be bootstrapped and timid to take any drastic action; yet, on the other hand, has an advantage to take decisive positions, depending on its values, internal strength and cohesion. In an extremely conflict-ridden society, where public opinion is divided and particular fault lines may crystallise, political leadership needs to harness public opinion towards concrete issues for well-meaning policies, to achieve democratic governance. Public groups too, for inclusivity and for strengthening and protecting democracy, need to democratise themselves; if they wish to be heard, they must practice the art of hearing from opponents. This fundamental logic of democracy applies to government, opposition, society and citizens alike – one must listen to others, for ownself being listened to! Democracy has high maintenance costs, but the investment makes sense for its minimum promise of maximum well-being for a maximum number of people.

During the lockdown period, several developments reflect the tensions of democratic governance in India. First, during the early days of lockdown, two “models” received wide attention in both mainstream and social media, for their ability to contain the spread of Covid-19: Bhilwara and Kerala. Bhilwara district in Rajasthan experienced an early outbreak of Covid-19; it was “described as the Wuhan and Italy of Rajasthan” fearing “community transmission stage” of a massive outbreak. The district collector (magistrate) of Bhilwara concluded, “ruthless containment is the only way to beat Covid-19,” by strictly ensuring that people stay indoors, with food and other necessities being delivered at their doorstep; yet acknowledged that this model cannot be applied in metropolitan cities with high-density population (Bhatt Reference Bhatt2020). Kerala also witnessed an early outbreak of Covid-19; it tackled the situation with empathetic attitude, patronising health workers, intensive testing and quarantine, meticulous observation on patients, learning from past, sheltering the migrants and providing cooked food to many (Masih Reference Masih2020; Vijayan Reference Vijayan2020). However, when a CPI(M) activist, KG shared the Washington Post news item on Kerala model in the MSMP Facebook group, five persons strongly refuted his claim, citing Kerala's smaller size; one of them, citing figures of the affected in several Kerala towns, ridicules that CPI(M) ultimately seeks validation from Washington Post. However, the models differ in their orientations, than strategies – Bhilwara model emphasises on “ruthlessness,” and “empathy” has been the core of Kerala model. At present, none of these models is heard anymore. As the pandemic acquires new dimensions, policy-communication has to proceed on the basis of available information from time to time, which is neither final, nor foolproof.

Secondly, both the groups have brought out news of police violence at times. In most cases, they relate to protests against the CAA and NRC that happened just before the lockdown. In MSMP, responses are mixed; but in TIL, police violence has been condemned consistently. With such discussions however, the government's views are communicated to people, by agreement or disagreement, because negative publicity is also publicity – the preferred information is disseminated! In the early days of lockdown, videos on police violence and humiliation of the “violators” were widely circulated and celebrated at times. A slogan was circulating on social media during this time: “haddiyan todenge kona kona, par na hone denge corona,” meaning: “will break every corners of the bones, but won't let corona to happen” (translation mine, from Hindi). The author of this slogan is not known, but certainly legitimised police violence against lockdown violators. Discussions on media may generate consciousness or express solidarity, but too inadequate to protect people-on-street from actual violence, particularly when public opinion is divided; many people, on the other hand, have expressed open support for police violence.

Many voluntary organisations have emerged during this time. The “Stranded Workers Action Network” (SWAN) provided “relief to workers stranded across India due to the COVID-19 lockdown” and “documenting their experiences”; a number of CSOs formed the “Covid Action Support Team” (CoAST) in April 2020 (SWAN 2020a). They networked with the existing CSOs and reached many parts of the country in a short time. In other words, civil society activism has mushroomed during the pandemic situation, to contest the government's claims, omissions and commissions. Many unpopular decisions were carried out during this time: government's bid to dilute labour-security provisions; rampant privatisation; amending democratic features of constitution – deleting words like “secular” and “socialist”; and drastic changes in school's social science syllabus. Some of them are politically explosive issues, but organising mass outrage requires concerted campaigning and mobilisation which is not easy during Covid-19, because insecurities and fear, arising from health catastrophe, generally distressed economic circumstances and police violence somewhat hinders mass-level political networking and mobilisation. Under this situation, CSO activism and dissemination of various social issues certainly contest the one-sided policy communication of government. It leads us to revisit the normative foundations of democratic governance; the state is accountable towards the security and well-being of its subject-population – the citizens.

Devaluing accountability: erosion of democratic space

Accountability rests upon three pillars: rulers and citizens agree to follow certain “standards,” in terms of norms, rules or procedures; “information,” to assess the extent of their compliance; and “sanctions” applied for omissions or commissions (Rubenstein Reference Rubenstein2007, pp. 617–18). More specifically, it mandates that government must explain citizens on the necessity of its decisions; officials shall serve people without favour to any external or partial interests; and citizens have access to adequate grievance-redressal mechanisms (Moncrieffe Reference Moncrieffe2001). As a primary and fundamental principle of democratic governance, accountability establishes the norm that governors' rule and decisions are validated by people.

In India, the Right to Information (RTI) is a definite milestone towards securing accountability from powerholders. It was enacted in 2005, after a series of popular movements, civil society activism and advocacy. RTI is a product of decades-long struggle, launched by common people, media and various CSOs in many parts of India against corruption, environmental degradation, human rights violation and other abuses of power (Baviskar Reference Baviskar2007; Goetz and Jenkins Reference Goetz and Jenkins2001; Sharma Reference Sharma2012; Singh Reference Singh2010). At times, RTI has been successful in empowering the weaker party to confront the powerful (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2018; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2007; RAAG and TAG 2014). Despite many limitations on its performances, RTI worked as a deterrent against abuses of power, by disturbing people misusing public power.

A disturbing development that undergoes the present regime, particularly with the outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic, is surreptitious shrinkage of democratic space in India, where accountability is often devalued; RTI is being increasingly observed in breach. At the same time, many actions and policies are initiated in ways that show the government's insensitivity or bypass the democratic channels. In addition, legislations having resulted from decades-long popular struggles to achieve people's empowerment and democratisation are disregarded. We shall notice these trends from four recent omissions and commissions. First, the government was caught in utter unpreparedness on the greatest human tragedy that has cropped up during the lockdown period – crises of the migrant labourers. Secondly, the Prime Minister's Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations Fund (PMCARES Fund) is kept outside the purview of public scrutiny, by questionable means. This is probably a direct assault on democratic governance. Thirdly, during the pandemic period, the syllabus content of social sciences in the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) has been drastically reduced. Fourthly, the suspension of question hours in both Houses of the Samshad has cast serious doubts on the government's commitment to democracy.

The migrant labour crises

Whereas the government, most notably the Prime Minister, has always been claiming the merits of “timely” lockdown, it has also been criticised as being unplanned and rash; in fact, it happened in four hours' notice. This has come to the fore with the crises of migrant workers. It reached the peak when sixteen migrant workers died on the railway tracks while returning back to their home on 8 May 2020 after lockdown was declared. Out of sheer exhaustion in the peak summer, for having walked around 45 km to reach home, they slept on the railway tracks thinking there would be no traffic. However, a goods train arrived, those who woke up tried to alert others, but failed. As a result, sixteen people died and one was injured (News18 2020). The ghastly pictures of their mowed down bodies and the pieces of bread that were strewn around the railway track were widely publicised both in mainstream and social media. It shook the nation's conscience to the hard reality of lockdown and the plight of migrant labourers that had already been in the news for previous few weeks.

Due to uneven economic development and socio-economic opportunities in India, migration is a reality. Many people leave home or villages for better livelihood options in places offering better socio-economic opportunities, particularly large cities. Migrants find their villages as more secure, yet authorities fear the spread of disease for their moving to villages, as it is easy to exercise surveillance on the cities (Arnold Reference Arnold2020). The government advised migrant workers to stay indoors during lockdown; but in reality, they feared eviction, for their inability to pay rents. In fact, many of them were unable to get daily essentials as income stopped; they had no choice but leave for home. Out of sheer desperation, migrant workers took to streets to walk back home under the blazing sun with family, children and belongings; some people collapsed due to fatigue, accidents and hunger. Meanwhile, the Centre directed the states to seal their borders; police violence and various sorts of humiliation had been heaped on the migrants – perceived to be carriers of disease. In Uttar Pradesh, pesticide was sprayed on the migrants to “sanitise” them (Jha and Pankaj Reference Jha, Pankaj and Samaddar2020, pp. 57–59).

Many stranded workers had to live with severely inadequate quantity of food; till mid-April, 95.97% of the stranded workers have not received any ration from the government; among the people who received rations, 49.88% were left with only one day's ration; 69.44% received no cooked food from any source. Delhi and Haryana had the best performances, where 60% could access cooked food (SWAN 2020b). An activist of the leading NGO, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, requested information from the Chief Labour Commissioner (CLC) on the details of migrant workers, in terms of gender, state and sector on 8 April 2020. After nearly a month, he received the reply that no such data are available (Nayak Reference Nayak2020). SWAN was even more scathing on criticism; its student and researcher-volunteers have documented 971 deaths not related to Covid-19 during the lockdown, which included factors such as police brutality, exhaustion, death at quarantine centres, accidents and suicides. SWAN wanted the government's data on the status of migrant workers and job loss, but when “no such data” were “available,” it accused the government being callous and inept, and sarcastically labelled its report as “no data, no problem.” It also refuted the government's claim on “Shramik Special” trains for transporting the migrant workers to home, because they were too inadequate compared to the magnitude of the crises; and were introduced more than a month after the crisis. Meanwhile, migrant workers were stranded in several cities “without cash and food” or any relief (SWAN 2020c). On the opening day's synopsis of business in Lok Sabha's monsoon session, not a single word has been uttered on the migrant workers' crises, despite visible and elaborate self-congratulatory accounts on the government's handling of the pandemic (Lok Sabha 2020a).

Subsequently, the central government has taken some measures to ameliorate the conditions of people, but quite inadequate to the continuing large-scale human misery arising from hunger and other hardships. During this period, a much publicised video showing the Prime Minister feeding peacocks (PM Modi's Precious Moments 2020) appears too un-aesthetic.

The PMCARES Fund

The PMCARES Fund is “a dedicated national fund,” set up as a response against Covid-19 type emergency situations, to meet the needs of affected population with relief, infrastructure and healthcare or medical facilities. It is a “charitable trust,” entirely based on voluntary contributions, but several important ministries such as Defence, Finance and Home Affairs are involved; and Prime Minister is the ex-officio Chairman of the fund. Both individual and corporate donors would qualify for income tax benefits as Corporate Social Responsibility (PMCARES 2020).

Several operations of PMCARES indicate blatant violations of accountability in many ways. First, a one-page audited statement of the receipts and payments in the financial year of 2019–2020 is provided; it was Rupees 3076.62 crores or 41.85 crores of US$ (1 crore = 100 billion). Secondly, any entity funded wholly or partially by the government is a public authority that comes under the purview of RTI. Here several government departments are involved. RTI activists filed queries, but the information was refused by the Central Public Information Officer (CPIO) of PMO, the Prime Minister's Office (Scroll Staff 2020a), on grounds that PMCARES is not a public authority. Media-reporting also points out CPIO's arbitrary nature of interpretation of “public authority”; Public Sector Units (PSUs) have contributed to PMCARES, and the fund was created by the Central government (The Wire Staff 2020). Thirdly, in the RTI portal of PMO, decisions between 12 June 2018 and 29 August 2018 are available (First Appeals Decisions undated). The decision that denied subjecting PMCARES to RTI is also not available. All these show an utter disregard for RTI – one of the greatest achievements of Indian democracy.

Opposition parties apprehended the fund's transparency. In the Lok Sabha session, an opposition Member of Parliament, in her lesser-than-six-minute speech, has vehemently criticised the government's handling of PMCARES Fund; since no tax-exemption is available for donation on the Chief Minister's relief funds, it in effect deprives the states having their due share, thus disregarding the spirit of federalism. Secondly, despite war-like situations with China, the Chinese army and banned companies were allowed to make contributions; and despite huge PSU contributions, the fund remains outside the purview of RTI. She points out the lack of transparency, where donations from local communities get lost into “dark hole where not even a speck of light can enter” (Mahua Moitra Speech 2020).

Curtailing social science syllabus

Another disturbing policy-decision during lockdown is the drastic reduction of CBSE social science syllabus. A comparison between CBSE syllabuses (CBSE Syllabus 2019, 2020) reveals that some highly pertinent issues have been eliminated: food security; democratic rights; culture and politics; forest life; popular struggles; religious reform and public debates; caste, gender and diversity; and challenges to democracy. Whereas the relevance of other issues to democracy is quite obvious, we need to discuss the relevance of forests for democracy and well-being of marginalised people in India. The Rights to Forest Act aimed to protect life, livelihood and culture of the indigenous communities as well as “for sustainable use, conservation of biodiversity and maintenance of ecological balance and thereby strengthening the conservation regime of the forests while ensuring livelihood and food security of the forest dwellings” (Forest Rights Act 2006, 2014). The targeted beneficiaries are traditionally marginalised people, whose lives are organically associated with forests over many centuries. Fears have been expressed for quite some time that the government may dilute the provision to deny existing rights; allow oppression and un-accountability by bureaucrats and armed forces; and finally hand over the precious and vast forest land to large corporations (Broome, Ajit and Tatpati Reference Broome, Ajit and Tatpati2019).

On 8 July 2020, CBSE issued a “Press Release” claiming that it was a “one-time measure,” in response to the media reactions to its notification of 7 July 2020 (CBSE Press Release 2020). However, despite many searches to the same website where this “Press Release” was found, the author failed to retrieve the “notification issued on 07.07.2020.” If the notice is removed or put into an obscure place, then the spirit of RTI, meant to ensure transparency in governance and administration, would be defeated.

Suspension of question hours

A news item started circulating in various news channels since the early September 2020 that the two Houses of the Samshad (Indian Parliament), Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha (Council of States), will not have “Question Hours” during the Monsoon Session starting from 14 September 2020. “Question Hours” are “direct democracy” in operation: “ministers are duty-bound to reply to every query posed by the members”; government policies on various issues are critically assessed during this time, where Ministers come into direct contact with members. The reasons cited for the suspension of “Question Hours” are the involvement of a large number of officials in the process; as a result, under the prevailing Covid-19 scenario, it would create difficulties in maintaining social distancing. The Opposition criticised the move as “murder of democracy,” and has been condemned by the media as well (Bhatnagar Reference Bhatnagar2020).

The Lok Sabha Secretariat dedicates a full section on questions, where the government is “put on its trial during the Question Hour”:

Asking of questions is an inherent and unfettered parliamentary right of members. It is during the Question Hour that the members can ask questions on every aspect of administration and Governmental activity. Government policies in national as well as international spheres come into sharp focus as the members try to elicit pertinent information during the Question Hour (Lok Sabha Secretariat 2020).

During this session, 230 questions were scheduled to be asked, 14 of them are on Covid-19-related issues (Lok Sabha 2020b). Yet, despite having browsed the impressively constructed websites of both the Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs and the Lok Sabha Secretariat, I failed to retrieve the exact notification where suspension of the “Question Hour” is published. This violates the Article 4(1-b) of RTI, which clearly requires every public authority to disseminate suo moto information – publishing every possible detail of the office.

Whereas the handling of migrant workers' crisis and PMCARES are visibly outrageous violation of state's responsibility and accountability, other erosions mentioned above do not appear that severe. Still, democratic rights and entitlements, even if eroded in apparently smaller ways, have worrisome implications. Such erosions generally remain unnoticed, yet get normalised and set a bad precedence. For example, “Question Hours” have been suspended in past too; every party, including INC and BJP, has records in wasting the allotted time (Bhatnagar Reference Bhatnagar2020); and the social science topics that have been deleted already had a “non-mandatory” nature. In addition, every detail of a right, entitlement or provision, when enacted, becomes a legally recognised infrastructure – if abolished or weakened for once, future endeavours for democratisation gets further retrogression.

A senior technocrat lamented “too much of a democracy in India” as a roadblock for achieving reforms (HT Correspondent 2020). Subsequently, he added qualifiers (Scroll Staff 2020b), but such tendencies have already started paying back dearly. The central government passed controversial bills on agricultural reform on September 2020, having implications for millions of livelihoods. It attracted strong and prolonged protest immediately and still continues vigorously, drawing adverse international publicity (Khan Reference Khan2020; Sharma Reference Sharma2021). This is certainly not the space to evaluate the Bills, but its hasty passage without adequate discussion in the Samshad hardly inspires any confidence.

We noted that democracy was already strained in many parts of the world even before Coivd-19. However, experiences in developing world substantiate that democracy is a better option to meet situations like pandemic, because people feel included when they can express voices in policy-making process. Alongside, opposition criticism and oversight keep the government on the right path, and ill-performing governments are defeated at polls (Youngs and Panchulidze Reference Youngs and Panchulidze2020). This core wisdom applies to India as well; the overall devaluation of accountability reflects the irritation of government with democratic procedures, particularly when its style of one-way communication is fairly well-known. However, once democracy is established, it becomes difficult to roll it back. Hence, powerful actors would be prudent to recast their strategies along the rules of democratic game. It is necessary to take tough decisions at times, but for endurance, governments must earn confidence from citizens – accountability facilitates achieving such confidence.

Multi-party democracy in India operates in the context of large population, high poverty, poor human development, and diversities along the lines of several languages, religions, castes and political ideologies. Harriss (Reference Harriss2020) argues that the populist nature of electoral politics, particularly in the lines of religion and caste, hinders democracy from addressing large-scale human miseries in India. Still, over the last two decades, several policy-decisions have resulted in alleviating human development deficiencies and poverty in India, though marginally (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2016). Democratic ethos is spreading into most hierarchical and disciplined organisations like the Indian army (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017). In the long run, given India's diverse and complex socio-political context, it is impossible to separate governance from democracy.

In fact, experiences of handling the pandemic show that where democracy asserted, better outcome in governance has been achieved. India's first-past-the-post system has enabled many governments to secure a comfortable majority in Lok Sabha, but no government has secured absolute majority from the combined electorate; it always remained at less than 50%. Hence, the society-government contradictions remain, and we have no indication that it will be resolved completely in foreseeable future. As a result, both for the regime's sustenance and legitimacy, it would be prudent not to tamper with the democratic process. Facing criticism from the opposition is an unpleasant experience, but it guides governance to proceed along the right path – the Prime Minister's elaborate account of welfare-measures; and at times, the government's desperate propaganda reflects the pressure of opposition-assertion. Any government, unless thoroughly demoralised, may improve its performances with opposition criticism; and with strong support from the legislature, the present government has no reason to feel demoralised. In addition, this also enables the government to improve its report-card before meeting the electorate next time; if the government performs well, the opposition starts with a disadvantage. Otherwise, society-government divide exacerbates, because the former remains virtually unrepresented in the latter. Democracy and governance are not dichotomous, rather complimentary to one another.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic that came to light in December 2019 continues to acquire newer forms from time to time. We have no exact and undisputed information about its beginning; and till now, the late-March 2021, we cannot see the end either; rather apprehend something worse. Under these circumstances, the government, as the manager of the political community, has crucial roles to play. The highest global body on health governance, WHO, is also caught unaware at times; and since the beginning, has repeatedly urged for strong leadership capable of mobilising the society thoroughly, to counter the menace.

Covid-19 also seems to have unfolded the reality that democracies have been under strain in many parts of the world over the last decade. Despite its ability to maintain satisfactory levels of democracy, thanks to the diverse nature of society and polity, contemporary Indian politics also reflect this tension. India is a multi-party democracy, at present ruled by the Hindu nationalist BJP, which enjoys absolute majority in the lower House of Samshad. In spite of keen electoral competition and the existence of various political ideologies, India faces the problem of abject poverty and poor human development index. It is necessary to remember this context for understanding India's response to the pandemic.

In response to Covid-19, WHO has particularly emphasised on sound governance. As an application of governance, policy-making and implementation often proceed through the path of uncertainty; hence it is not fair to expect the government to resolve crisis situations accurately and comprehensively. In Indian context, the issue of governance has manifested along two tracks vis-à-vis the pandemic: policy-communication and accountability. First, the process of policy-communication happened most visibly through the Prime Minister's frequent addresses to the nation, particularly while implementing the hard decision of lockdown. The deep involvement of social media reflected multi-dimensional nature of the issue; people speaking on their behalf reflected the diversity of public opinion – the social context of policy-communication.

Secondly, during this period, the government attempted to bypass the usual democratic channels through various omissions and commissions, but the opposition and CSOs/NGOs made concerted efforts to contest such tendencies, and prodded the government to address many pressing issues. It occurs that in India, democracy is indispensible for sound governance. Strong leadership is necessary for decisive courses of action, where quick decisions may often be necessary; and policies formulated need to be communicated appropriately from state to society. However, it is also necessary to realise that democracy is not an irritant; rather when rulers respect accountability to people, democracy serves to provide foundations for sensible decisions and decisive actions. Together, they weave the context of democratic governance.