To the Editor—Infection control (now infection prevention) in healthcare settings is a relatively young medical discipline dating back only to the 1970s. Nationwide surveillance for healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) was initiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1970 via the National Nosocomial Infections Study (NNIS). The scientific foundation for infection prevention was established by the Study on the Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection Control (SENIC) project that demonstrated essential components of effective programs included (1) conducting organized surveillance and control activities and (2) having a trained, effectual infection control physician, (3) having an infection control nurse per 250 beds, and (4) having a system for reporting infection rates to practicing surgeons. Reference Haley, Culver and White1 The SENIC project also reported the growth in the number of hospitals having an infection prevention nurse (from 6% prior to 1970 to 80% in 1977). Reference Emori, Haley and Stanley2 However, by 1996 only 47.6% of facilities has a hospital epidemiologist. Reference Nguyêñ, Proctor, Sinkowitz-Cochran, Garret and Jarvis3

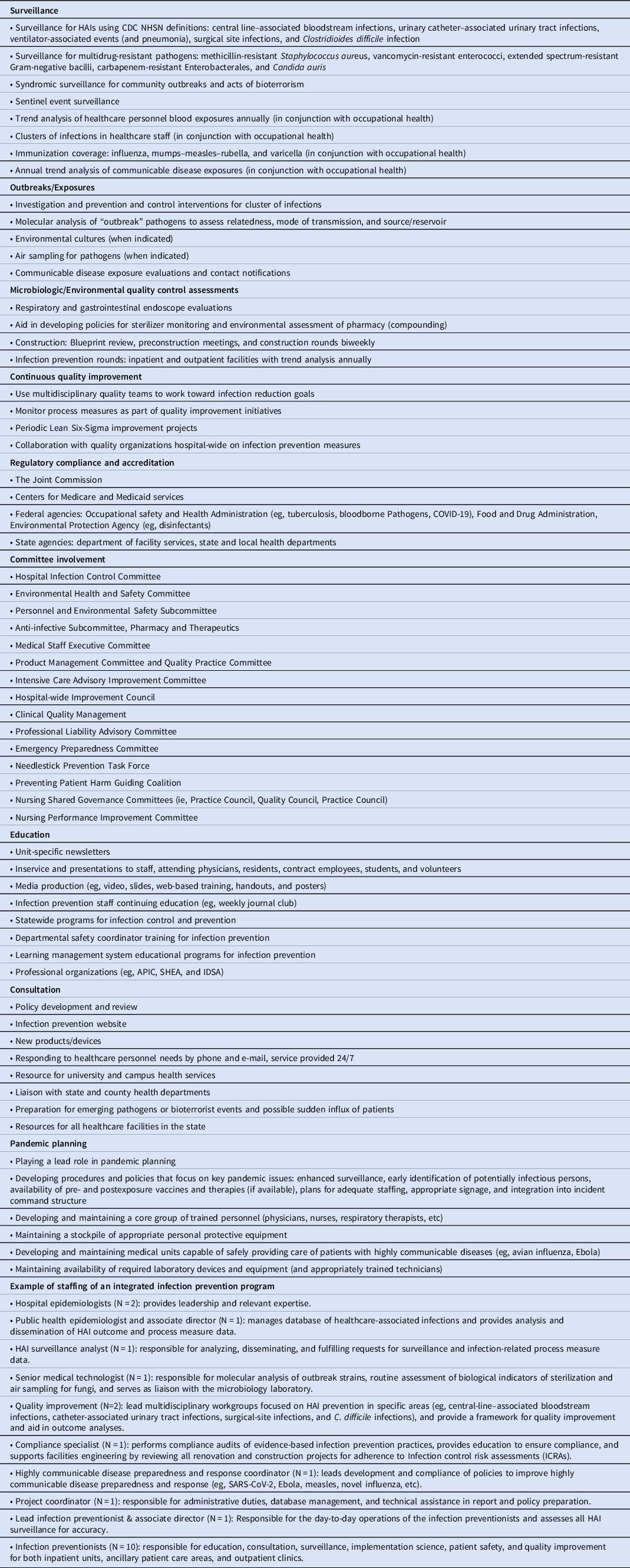

The initial focus of infection prevention departments was surveillance for HAIs, outbreak evaluations and control, and reduction of device-associated HAIs. In the past 50 years, the spectrum of activities of an infection program has dramatically increased to include the following: (1) surveillance and prevention of multidrug-resistant pathogens (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, β-lactamase–producing gram-negative bacilli, carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales, Candida auris); 4,Reference Blake, Choi and Dantas5 (2) prevention of Clostridioides difficile; (3) recognition and mitigation of biothreats (eg, anthrax), and emerging infectious diseases (eg, Ebola SARS-CoV-2); (4) public reporting to multiple agencies rating hospitals; and (5) financial penalties for hospitals by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for “poor” performance including high HAI rates. The most important of these may be the paradigm shift from “control” of HAIs to “prevention” of all HAIs (ie, the goal is now zero HAIs) (Table 1).

Table 1. Infection Prevention: Scope of Service and Example of an Integrated Program

Infection prevention programs have access to several new tools to aid in the prevention of HAIs: (1) widespread use of electronic medical records that allow more complete and efficient access to medical records documentation; (2) improved information technologies that allow for data mining, manipulation of large data sets, easier use of sophisticated statistics, and machine learning Reference Luz, Vollmer, Decruyenaere, Nijsten, Glasner and Sinha6 ; (3) improved microbiology laboratory methods that aid in determining microbe transmission pathways and outbreak investigations (eg, MALDI-TOF and whole-genome sequencing) as well as rapid microbe identification methods (eg, PCR) Reference Blake, Choi and Dantas5,Reference Boccia, Pasquarella and Colotto7 ; and (4) quality improvement methodology that allows a more systematic approach to identifying problems and then implementing evidence-based infection prevention efforts.

As infection prevention has grown both more complex but also more sophisticated, infection prevention programs have 2 options as they adapt to this new reality. First, their staff can continue to be composed of hospital epidemiologists and infection preventionists with the infection prevention department reaching out to other hospital departments for expertise in quality improvement, informatics, advanced epidemiologic and statistical methods, advanced microbiologic methods, and compliance monitoring and coaching. Reference Buchanan, Summerlin-Long, DiBiase, Sickbert-Bennett and Weber8 Second, they can accept the new paradigm of evolving into a truly integrated department (Table 1). Based on our experience at the University of North Carolina Medical Center, the advantages of an integrated department are substantial and include the following: (1) ability to approach all infection prevention and control activities (eg, outbreaks, HAI reduction, emerging diseases and pandemics) using a multidisciplinary approach; (2) rapid access to required expertise; (3) ability to ensure needed expertise for long-term improvement projects; (4) cross pollination of infection prevention knowledge with other disciplines, improving ability to reduce HAIs; and (5) taking the lead in planning for future pandemics. Reference Weber, Rutala, Fischer, Kanamori and Sickbert-Bennett9 Most importantly, staff with training in nonclinical medicine (eg, quality improvement, informatics, and compliance monitoring) have time to also develop a broad and deep background in the enormous literature of infectious diseases, hospital epidemiology and infection prevention. For example, they become knowledgeable about guidelines on HAI prevention set out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and professional organizations. Finally, having a department with an integrated team with diverse expertise can enhance professional satisfaction in a field often without many opportunities for traditional upward mobility or promotion opportunities. In addition, having a motivated workforce may reduce staff burnout, improve job satisfaction, and contribute to a positive workplace culture.

Additional programs might be evaluated as part of an integrated infection prevention department. First, development of a formal “infection prevention liaison” program may be considered. Such a program should include a member from each clinical (eg, medical intensive care unit) and nonclinical unit (eg, radiology) that meets at least once a month with key members of the infection prevention department and receives periodic infection prevention lectures and updates. Liaisons can serve as 2-way communicators (ie, updating their units with the latest infection prevention policies and providing feedback from individual units to infection prevention leadership). Second, infection prevention can be integrated with antimicrobial stewardship programs (CDC recommendations). 10 Antimicrobial stewardship plays a key role in C. difficile reduction and control of multidrug-resistant pathogens. For example, at the University of North Carolina Medical Center, the Director of Infection Prevention also serves as the Administrative Director of Antimicrobial Stewardship. In addition, members of the antimicrobial stewardship team play a key role in advising on issues relating to diagnostic stewardship (eg, appropriate collection of blood cultures and indications for urinalysis or urine culturing). Successful antimicrobial stewardship programs are also multidisciplinary in nature, so direct alignment with the infection prevention team can provide synergistic support and strategy.

In conclusion, we believe that an integrated infection prevention department should be considered as the paradigm of the future. Such a department will be better equipped to achieve zero HAIs as the ultimate goal and will be better prepared to respond to future pandemics.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.