To the Editor—Privacy curtains are an understudied potential vector for pathogen transmission. Reference Fijan and Turk1,Reference Mitchell, Dancer, Anderson and Dehn2 They are ubiquitous in healthcare facilities and are touched frequently by healthcare workers (HCWs), often between hand hygiene and patient interactions. Reference Shek, Patidar and Kohja3–Reference Sehulster6 Also, they are infrequently changed or cleaned. Best practices in terms of the optimal materials and usage have not been well established. In this study, we evaluated the microbial concordance and strain similarity between multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) contamination of curtains and patient colonization.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted in 6 nursing homes in southeast Michigan between November 2013 and May 2016. Reference Mody, Foxman and Bradley7 After obtaining informed consent, we obtained cultures from several patient body sites and high-touch surfaces in the patient rooms, including the privacy curtain, at admission, day 14, day 30 and monthly thereafter up to 6 months. Reference Cassone, Mantey and Perri8 Age, sex, race, and risk factors for MDRO colonization (functional disability, Reference Lawton and Brody9 indwelling devices, comorbidities, prior antibiotic use, hospitalization length), and data on facility curtain changing policies were collected. The University of Michigan institutional review board approved the study.

At each visit, swabs (Bacti-swabs, Remel, Lenexa, Kansas) were used to sample patient body sites (dominant hand, nares, oropharynx, groin, perianal area, wounds if present, enteral feeding tube insertion site, suprapubic catheter site) and high-touch surfaces (bed controls, bedside table, nurse call button, privacy curtain, toilet seat, door knob, television remote control, bed rail, wheelchair handles) in the patient’s room as previously described. Reference Cassone, Mantey and Perri8 For privacy curtains, an area of ∼43 cm Reference Mitchell, Dancer, Anderson and Dehn2 was swabbed from the leading edge of the flame-retardant polyester curtain.

Swabs were cultured for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), and resistant gram-negative bacilli (R-GNB). Reference Mody, Foxman and Bradley7 Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on a subset of MRSA and VRE isolates as previously described. Reference Cassone, Mantey and Perri8 Isolates were placed in the same pulsotype if their SmaI restriction patterns were ≥80% similar.

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients with an MDRO-contaminated curtain at any point in the study and those with no contamination. The Student t test was used to compare continuous variables; the Pearson χ2 test and the Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. The relationship between curtain MDRO contamination and patient MDRO colonization were calculated using χ2 tests.

Results

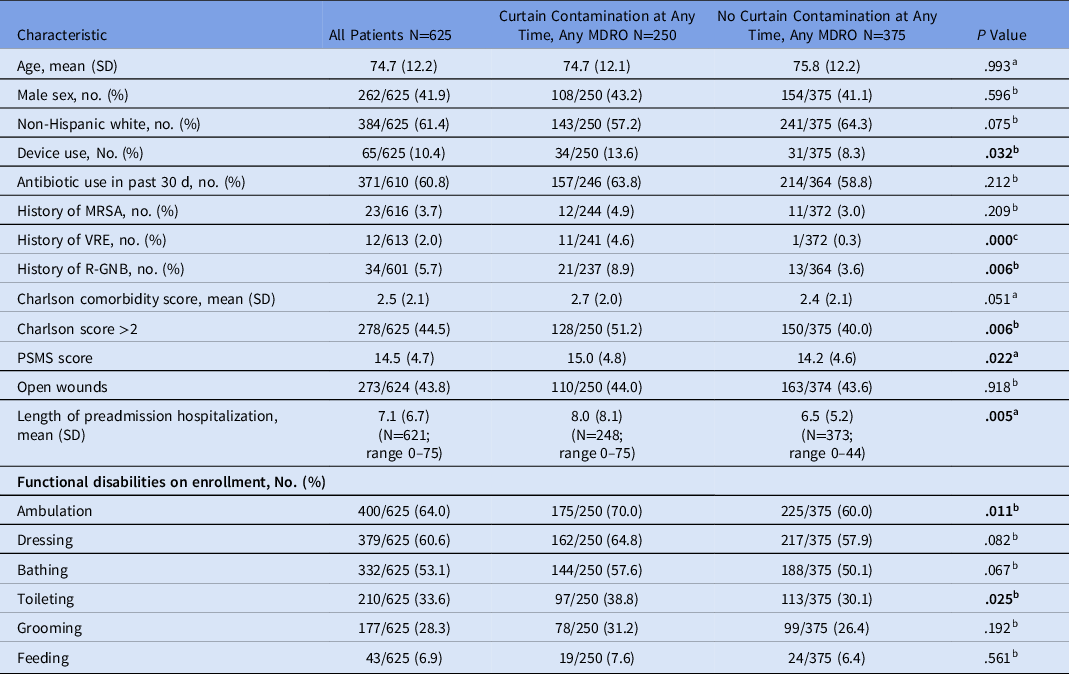

Of the 625 study patients, 250 (40.0%) had an MDRO-contaminated privacy curtain at some point during the study. Those patients were more likely to have an indwelling device in place, multiple comorbidities, a higher PSMS score, a longer hospital stay prior to nursing home admission, and disabilities related to ambulation and toileting (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Nursing Home Patients on Enrollment

Note. MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism; SD, standard deviation; PSMS, Physical Self-Maintenance Scale.

a Calculated using a 2-sided t test.

b Calculated using the Pearson χ2 test.

c Calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Of 1,521 total curtain samples, 334 (22.0%) were contaminated with an MDRO, including 210 (13.8%) with VRE, 94 (6.2%) with R-GNB, and 74 (4.9%) with MRSA (Supplementary Table 1 online). The most commonly isolated R-GNB were Pantoea spp (47 isolates), Acinetobacter baumannii (21 isolates), and Enterobacter cloacae (10 isolates). MDRO prevalence varied among facilities, ranging from 11.9% to 28.5% (VRE, 7.1%–17.6%; R-GNB, 2.0%– 11.6%; MRSA, 2.8%–8.8%). There were 36 cases (8.8% of at-risk patients) of new MRSA curtain contamination and 56 cases (15.8% of at-risk patients) of new VRE contamination. In 47 (51.0%) instances, MRSA or VRE patient colonization preceded the positive curtain sample. Among instances in which isolates from the curtain as well as the patient and/or the environment were available, identical PFGE patterns were identified in 15 of 19 visits (78.9%) for MRSA and 14 of 25 visits (56.0%) for VRE (Supplementary Table 2 online).

Discussion

We found high rates of MDRO contamination among privacy curtains in occupied rooms at 6 nursing facilities. Of 625 patients, 250 (40%) had an MDRO isolated from his or her privacy curtain at some point (334 of 1,521 samples, 22% of sampling visits), and VRE was the most common (13.8% of samples). New MDRO curtain contamination occurred predominantly in rooms with preexisting patient colonization, often with matching isolates.

Privacy curtains serve an important role in healthcare settings, but they are a potential pathogen reservoir due to large surface area and frequent contact by HCWs and patients. Reference Fijan and Turk1–Reference Ohl, Schweizer, Graham, Heilmann, Boyken and Diekema4,Reference Sehulster6 Prior studies in intensive care units have reported rapid MRSA or VRE contamination, within 1 week of new curtain placement. Reference Ohl, Schweizer, Graham, Heilmann, Boyken and Diekema4,Reference Schweizer, Graham, Ohl, Heilmann, Boyken and Diekema5 Transmission of bacteria to HCW hands occurs after 50% of curtain contacts. Reference Larocque, Carver, Bertrand, McGeer, McLeod and Borgundvaag10 Our study showed the more common sequence of events to be patient colonization followed by curtain contamination; however, in some cases in which curtain contamination preceded the patient colonization, the curtain was a plausible source of transmission to patients.

In this hypothesis-generating study, we did not assess the directionality of MDRO contamination or quantify the level of curtain contamination. Curtain cleaning practices, optimal frequency of cleaning, and any potential transmission to roommates should be investigated in-depth. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of curtain contamination in nursing home settings, in which the prevalence of MDRO patient colonization is particularly high. Widespread curtain contamination has been linked to lack of regular disinfection or replacement. Reference Sehulster6 Antimicrobial curtains, including antimicrobial textile technology, have been studied as a potential solution. Reference Schweizer, Graham, Ohl, Heilmann, Boyken and Diekema5

Action can and should be taken to decrease curtain contamination, including standard practice guidelines for cleaning or replacing curtains, and implementation of simple strategies, such as better handwashing by medical staff, patients, and visitors, while also considering alternative designs, such as removable handles, retractable partitions, and argon glass doors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all nursing home patients and HCWs who participated in this research study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. RO1 AG041780 and K24 AG050685).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.60