A sudden and rapid influx of patients in acute care occurred in March 2020 in the Netherlands, when the new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–specific infection prevention policies were not fully developed. Scarcity of personal protective equipment (PPE), nearly reaching the maximum capacity of hospitals, and the enormous workload for healthcare workers (HCWs), forced many hospitals to decide to cohort patients with COVID-19. Other considerations in choosing cohorting were hospital design with predominantly multiple-occupancy rooms, lack of capacity to isolate each patient in a single-patient room with doors closed, and expecting to provide more efficient patient care.

In cohorts, the doors of COVID-19 patients rooms remain open. These rooms can either be multiple-occupancy or single-patient rooms or a mix of both, but in all cases, the rooms, including enclosed parts on the ward, are used to care for proven COVID-19 patients. The entire cohort ward is considered contaminated; therefore, only controlled entry to the ward is allowed. 1 Consequently, PPE has to be worn when entering the cohort ward and during whole shifts. PPE has to be changed after wearing it for 3–6 consecutive hours with different patients. 2,3 Mainly, since the effectiveness of surgical face masks will be reduced after this time, but also because of eating, drinking, and bathroom use, which should take place outside the ward. All PPE should be removed when leaving the cohort ward. On wards where COVID-19 patients are only isolated in single-patient rooms with doors closed, only that patient room is considered contaminated. Non–COVID-19 patients in other (adjacent) rooms at the same ward can be cared for without using extra PPE. Here, we describe our investigation of whether cohorting or isolation in single-patient rooms with doors closed saves PPE. We highlight the advantages and disadvantages of organizing patient care in cohort wards or in single-patient rooms with doors closed.

PPE use was observed in the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre Rotterdam (Erasmus MC), during the first peak of COVID-19 in the Netherlands, in March–April 2020. COVID-19 patients were cared for in single-patient rooms with doors closed; we did not create cohorts. This type of isolation was most obvious because our hospital consists of 100% single-patient rooms for adults. Trained medical students counted the number of HCWs who entered single-patient rooms, while wearing a full PPE set, during 4 busy hours in the morning. One PPE set (ie, gloves, face mask, eye protection, gown) to be used for COVID-19 patients, was considered equivalent to 1 HCW entering the room.

The use of 278 PPE was observed on 2 general wards (ie, wards 1 and 2) and 3 ICUs (ie, wards 3, 4, and 5) between April 14, 2020, and May 1, 2020. The frequencies of PPE use observed for 1 patient in 4 hours were 7 for ward 1, 8 for ward 2, 7 for ward 3, 9 for ward 4, and 8 for ward 5. The data show no large differences in PPE use between a general ward and an intensive care unit (ICU). On average, 8 PPE (standard deviation [SD], 0.7) were used to care for 1 patient in 4 hours.

According to the Dutch guideline, every 3 hours, a face mask has to be changed while working in a cohort due to expiration. 2 Therefore, we calculated PPE use when caring for 1 patient in 3 hours, which was 6 PPE. When we multiply this number with the total number of patients hospitalized on the ward during the observation, we were able to estimate the total PPE use in the observed ward. This value could then be used as a break-even point for installing a cohort situation. The PPE use in 3 hours for the entire ward was 234 PPE (39 admitted patients) for wards 1 and 2; 198 PPE (33 admitted patients) for ward 3; 132 PPE (22 admitted patients) for ward 4; and 36 PPE (6 admitted patients) for ward 5. On average, 167 PPE were used in a cohort every 3 hours.

When a cohort uses <6 PPE per patient per 3 hours, the hospital will save PPE compared to isolation in single-patient room setting with doors closed. These calculated cohort situations suggest that, with small groups of patients, PPE use is more likely to exceed the break-even point faster, which makes isolation in single-patient room with doors closed more efficient. However, cohorting would probably be more efficient when isolating larger patient groups.

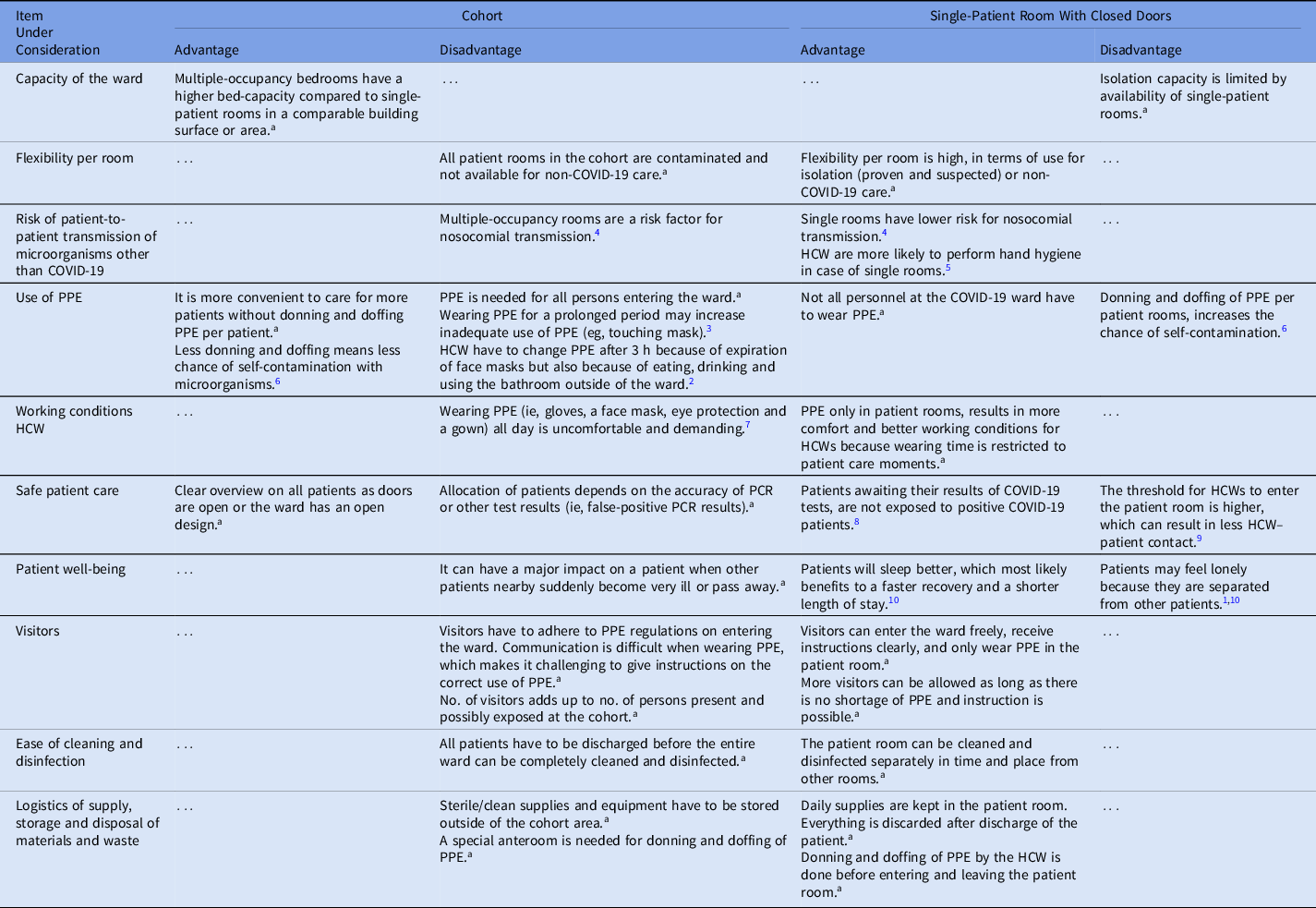

Apart from efficiency, several other factors can guide the choice for COVID-19 care in cohorted wards or single-patient rooms. Therefore, we have presented the advantages and disadvantages of both types of isolation, based on literature and expert opinion in Table 1. By including published literature and expert opinion, we have provided a complete overview of the issues to consider when deciding on the isolation organization of COVID-19 patients in the hospital. One limitation of our study is that we may have overestimated our observations because we observed PPE use during the busiest hour of the morning. We expect that less PPE is used during other working hours.

Table 1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Cohorting Versus Single-Patient Room Care

Note. HCW, healthcare workers; PPE, personal protective equipment; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Expert opinion/ experience.

In conclusion, before choosing isolation in single-patient rooms with doors closed or establishing a cohort, it is important to consider the expected usage of PPE with respect to the number of COVID-19 patients as well as the specific advantages and disadvantages of the options.

Acknowledgments

We extend our appreciation to the infection prevention unit, the healthcare personnel of the COVID-19 wards of the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and the students who performed the observations.

Financial support

No specific funding was provided for this study because the obtained data resulted from an ongoing COVID-19 surveillance program in the Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.