I

In 1632, Charles I commissioned one of the defining images both of his reign and of his government, ‘One greate peece of O[u]r royall selfe, Consort and children’ (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 In Van Dyck's monumental group portrait, private and public roles coalesce. Domestic imagery is employed to support political rhetoric, with the king figured exercising his paternal authority over both his family and his subjects. Charles sits, his right arm enclosing his young heir, who rests a small hand on his father's knee, pointing up towards the king. Henrietta Maria, in turn, props up the figure of her baby daughter and contemplates her husband with an intent regard. This air of immediacy and informality, however, belies the painting's complex allusions. Subtle networks of exchanged gestures and glances connect the family members, emphasizing affective bonds while also underlining hierarchical relationships. Even the presence of two twitchy Italian greyhounds, representative of fidelity and obedience, support this projection of a devoted and well-ordered household. Yet this apparent intimacy is supplanted by a grandiose stage-set, dressed with the trappings of Stuart power. To Charles's right, placed upon a table swathed in crimson, sit the crown, sceptre, and orb, while beyond, discernible through the murky clouds of an unsettled sky are the silhouettes of Westminster Hall and the Parliament House, the administrative and legislative centres of the kingdom. By inference, the harmony pictured in this royal family grouping extends outward to the realm and its people. Charles is proclaimed as a father king, who guides and protects the common good as he does his children. His depiction as loving paterfamilias supports his status as pater patriae.

Figure 1. Anthony van Dyck, Charles I and Henrietta Maria with their two eldest children, Prince Charles and Princess Mary, 1632. Oil on canvas, 303.8 x 256.5 cm. Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

The ‘greate peece’ has been designated ‘one of the most important texts of early modern kingship’.Footnote 2 Indeed, images of Charles I's family were to become central to the representation of his reign until its premature end, following his execution in 1649. Their combination of domestic associations and authoritarian overtones can be discerned in royal family portraits throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 3 This article will consider a different legacy, however, exploring how Van Dyck's depiction of politicized domesticity in Stuart portraiture was revised and reworked in a number of nineteenth-century historical genre paintings. By so doing, it considers how these later compositions materialized the Caroline past for modern audiences, assessing the role of the visual in the historical imagination and probing shifting processes of remembering. Reimagining Stuart family life, these nineteenth-century paintings constituted multi-layered mediators through which viewers might look both back and forward. Enlisting audiences in an involved, participatory engagement with the past, they served to negate temporal distance and to promote historical proximity. Analysis of these overlooked images, therefore, offers new insight into encounters and relationships with the past, during a critical period in the development of historical consciousness in Britain.Footnote 4

Historical perception is rarely static but alters and fluctuates. Throughout time, the present has renegotiated its relationship with the past.Footnote 5 Of course, the appropriation and manipulation of Charles I's image was nothing new. With the publication of his autobiography, Eikon Basilike (1649), just days after the king's execution, his representation was popularized, exposed to an image-making process which was ‘collective, collaborative and participatory’.Footnote 6 The post-Restoration regime celebrated Charles as saint-like martyr, while the Jacobites, in turn, adopted him as an icon of suffering and hope.Footnote 7 Later, parallels between the English and French Revolutions recast his biography as cautionary, a precedent from which both royalists and republicans might learn.Footnote 8 In the nineteenth century, Charles's portrayal continued to acquire new meanings. The English Revolution encroached on the Victorian mindset like no other historical struggle.Footnote 9 It was perceived as the source from which civil liberties and the constitutional monarchy originated, while its controversies had left long-standing political fissures that still troubled the nation.Footnote 10 At the same time, the Caroline era also supplied an appealing prototype for nineteenth-century family life. The Victorian cult of domesticity exalted home and household as the foundations of civilized society.Footnote 11 In Van Dyck's images of Charles I and his family, viewers saw a historical model for their own idealized private lives.Footnote 12 Yet, touched by his depiction of royal familial harmony, they also recognized a warning from the past. Political and domestic concerns were intertwined in readings of these images and viewers knew how the story ended. Accordingly, historical genre paintings of the royal family serialized the tragedy of the hapless Stuarts, connecting a glimpse of ‘history-in-the-making with its final significance’.Footnote 13

In the nineteenth century, understanding of the past was formed through an unprecedented expansion of historical culture. A new awareness permeated the middle classes in the first half of the century, with a historically minded mass audience developing by its end.Footnote 14 In a democratization of historical experience, this awareness was shaped not only through the texts of such distinguished scholars as Thomas Babington Macaulay and Thomas Carlyle but also through popular volumes, works of fiction, and, importantly, through visual culture.Footnote 15 The nineteenth-century visualization of history presented new ways of viewing the past. A pictorial historiography developed, made up of retrospective artistic representations, both painted and printed. These images were reductive, abridging history into a series of dramatic scenes but they were also accessible and immediate. What is more, they shifted the onus of interpretation from the historian to the viewer, opening up historical meaning.Footnote 16 Mark Salber Phillips has asserted that historical representations produce different effects of distance, mediating our encounters with the past.Footnote 17 The spectrum runs from remoteness to proximity. As he argues, the detachment of the former offers clarity and perspective, while the intimacy of the latter encourages insight and connection.Footnote 18 Phillips identifies four dimensions of representation that shape our experience of time: form, affect, ideology, and cognition.Footnote 19 My aim here is to complement and supplement this analysis, exploring how nineteenth-century visual culture fashioned historical proximity by reaching beyond the frame to form a series of connections. Adapting Phillips's linear conception of distance, I argue that images of Charles I and his family lie at the centre of a network, where the audience's intellectual, emotional and associative responses intersect to encourage a sense of intimacy. By simultaneously invoking recognition, sympathy and communality, these paintings reshaped time. Relationships between original and derivative, text and image, past and present encouraged an active viewing and rendered Stuart history close-up.

II

Commenting in 1879 on Van Dyck's portraits of Charles I, one of the artist's first English biographers, Percy Rendell Head, remarked: ‘On the countenance of mournful dignity there rests a shadow of trouble past and to come, which, read by the light of history, seems like a revelation of the future.’Footnote 20 In his later study of the painter, Lionel Cust, director of the National Portrait Gallery, went further:

It is the Charles I of Van Dyck whom the historian pictures to himself, defying the House of Commons, receiving the news of Naseby or Edgehill, the Captive of Hampton Court or Carisbrooke, or the royal martyr, pacing with undiminished dignity and pride through the snowy morning to the last scene of the scaffold of Whitehall. For all these scenes Van Dyck prepares the illustration.Footnote 21

Both commentaries illustrate the extent to which Van Dyck's portrayal of the king had penetrated nineteenth-century historical memory. Indeed, Head acknowledges the significant role of the artist in constructing an alluring and enduring image of the Caroline royal family, pronouncing Van Dyck largely responsible for ‘the strangely passionate affection with which a large section of the English people [have] long cherished the remembrance of the unhappy and unprofitable Stuarts’.Footnote 22 Van Dyck's royal portraits were displayed in public collections and temporary exhibitions, while reproductions entered the middle-class home as engravings, book illustrations, and images in periodicals.Footnote 23 To nineteenth-century audiences, then, his paintings were agents for narratives and visions of the past, while simultaneously becoming embedded with meanings and resonances beyond their original situations and intentions. In retrospect, Van Dyck's works were re-read and re-remembered. The royal portraits were now premonitions, pictorial presentiments of the Caroline tragedy. Indeed, in Sir Walter Scott's historical novel, Woodstock (1826), Cromwell, himself, is portrayed brooding over a Van Dyck portrait of the late king only to predict that ‘our grandchildren, while they read his history, may look on his image, and compare the melancholy features with the woful [sic] tale’.Footnote 24 Historical genre paintings of the Stuarts extended this process of reimagining. Some played upon the audience's knowledge of what was to come, presenting them with a fictional scene of Stuart domestic harmony and happiness soon to be shattered, while others pictured the next chapter in the story, visualizing the forced separation of the royal family and foreshadowing the imminent loss of its head. Perceptions of Van Dyck's compositions and the advent of their nineteenth-century successors point to a cyclical relationship, where retrospective interpretations of his original pictures inspired a series of derivative ‘spin-off’ images. These pictorial scions, in turn, came to influence readings of, and responses to, their prototypes. Significantly, this process illustrates the formation of an unfolding, episodic Stuart historical drama in the public imagination. Indeed, for those later pictures, recognition both of the situational present and of its temporal connections was central to imparting historical proximity.

The complex sequence of invention and reinvention, from Van Dyck's initial pictorial construction of the Stuart family to the nineteenth-century painters’ later visual reimagining, is pulled into focus in John Everett Millais's oil sketch for a lost composition, Charles I and his son in the studio of Van Dyck (1849, see Figure 2). In the early 1840s, two other artists, Ferdinand Pickering and Samuel West, had exhibited paintings with a similar theme. Both Pickering's A visit to Vandyck (1841) and West's Charles I receiving instruction in drawing from Rubens, whilst sketching the portraits of his queen and child (1842) appear to have emphasized the king's close relationships with his court painters, while conforming to the familiar image of Charles as an involved and affectionate husband and father.Footnote 25 Millais sets his scene in the artist's studio. Palette in hand, Van Dyck works on a small head-and-shoulders portrait of the king, who sits enthroned before him. The screens behind Charles, the suit of armour on display and the edge of a gilt mirror, in which the artist is reflected, all support the sense that this is a moment of artistic image-making, of artifice and pretence. Yet, leaning into the king's figure, in a tender embrace, is a young golden-haired prince, who smiles towards the painter. The gesture contributes an impression of natural feeling and informal emotion. The audience is privy not to the creation of an official state portrait but to that of an intimate keepsake – a snapshot of Caroline domestic bliss. The fatherly care and affective ties depicted in Van Dyck's canvases have been magnified. Thus, paradoxically, Millais seemingly acknowledges the court artist's agency and the construction of a Caroline family image, while accepting and conforming to succeeding sentimental narratives. The canvas on which his Van Dyck daubs is pure fantasy, reflecting not Stuart but Victorian sensibilities and reflexively highlighting Millais's own part in this painterly revision of history. Certainly, painters did not misrecognize or misunderstand dynastic representations, they consciously re-presented them. Indeed, what had been a pictorial political statement was transformed into an evolving and involving visual narrative. Representations of the Stuarts now formed a succession of scenes that depicted a present in which temporal links and alignments were inherent. In picturing Van Dyck at work, Millais signalled back to the old master's actual royal portraits. Yet, in depicting a moment of happiness, of paternal regard and filial affection, albeit an imagined one, he also motioned forward to the moments of unhappiness yet to come. Sharing in an uncomfortable awareness, audiences were drawn in through their knowledge of significances beyond the canvas itself.

Figure 2. John Everett Millais, Charles I and his son in the studio of Van Dyck, 1849. Oil on wood, 15.9 x 11.4 cm. Presented by Henry Vaughan 1900. Photo: Tate.

Even in its title, Frederick Goodall's An episode in the happier days of Charles I (1853, see Figure 3), implicitly points towards events outside the picture frame. In this painting, Charles and his family take an idyllic cruise along the Thames on a richly decorated barge. Clad in black, a striking and ominous contrast with his colourfully attired wife and offspring, the king has set aside his reading to watch his children feed the swans. Leaning against the canopied tilt, the doting father surveys a charming scene. With a spaniel perched on her lap, Henrietta Maria gently cradles one of her daughter's hands, while the diminutive rosy-faced child offers a piece of bread to an approaching bird. The couple's other children and retainers look on serenely. Meanwhile, the oarsmen row the shallop toward its mooring, where a small crowd awaits the royal passengers. Charles, himself, is closely modelled on Van Dyck's half-length portrait type, dating from the late 1630s (1635–7, see Figure 4), which portrays the king dressed in black, the silver star of the Order of the Garter emblazoned on his cloak. One of his hands rests upon his discarded hat, the other clutches a pair of gloves – both of which Charles wears in Goodall's composition. Fidelity to his prototypes was evidently of concern to the artist, who sought permission from Queen Victoria to study Van Dyck's portraits at Windsor.Footnote 26 In particular, he spent several weeks ‘making studies from the Vandyck picture of “Charles, Henrietta Maria and the Children”’.Footnote 27 In the nineteenth century, the ‘greate peece’ was, indeed, installed at Windsor so it is clear to which picture Goodall devoted his attention.Footnote 28 With the exception of Charles, however, Goodall's portrayal of the Stuart royal family is largely invented. While the queen's form constitutes an approximation of her portraiture, the children are essentially imaginary figures, composite creations that merge Vandyckian and Victorian conceptions of childhood. The result is a mediated authenticity, a construction of passing historical truth that lends credence to the sentimentalized scene. Blurring the lines between fact and fiction, between imagined and actual histories, again supported a mythologized story-telling, in which relationships between past, present, and future came to the fore. This invented and heavily glossed ‘episode’ looks forward to impending genuine events. Indeed, such was its narrative power that it became a major plot device in W. G. Wills's play, Charles I, performed at London's Lyceum Theatre in 1872. Goodall's composition was realized in tableaux at the end of the first act.Footnote 29 Commenting on his original painting, the theatre critic for The Times observed:

The sentiment awakened by a contemplation of this picture would lie dormant did not the imagination of the spectator wander beyond the limits of the scene presented to his eyes, until it reached the scaffold at Whitehall. It is the knowledge of the unhappiness by which the happy days were followed which gives the subject interest.Footnote 30

Figure 3. Frederick Goodall, An episode in the happier days of Charles I, 1853. Oil on canvas, 99.5 x 153.5 cm. Bury Art Museum & Sculpture Centre, UK © Bury Art Museum & Sculpture Centre /Bridgeman Images.

Figure 4. After Anthony van Dyck, King Charles I, 1635–7. Oil on canvas, 123.2 x 99.1 cm. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Thus, the reviewer pinpoints the internal process through which audiences recognized the painted present and mentally realized the historical future. It is this response that, he states, ‘links together the several parts’ of the play's somewhat disjointed historical narrative.Footnote 31 Again, the nineteenth-century public's understanding of Stuart history as a serialized progression is apparent in the critic's remarks. It was this impression that historical genre paintings drew on to engage the viewer. In looking back, artists sought to establish authenticity, appropriating and adapting Van Dyck's motifs to imbue their works with the illusion of realism. In looking forward, they imbued their compositions with pathos, encouraging the viewer to envisage actions outside the canvas, an unfortunate future passed. By so doing, audiences at once grasped the significance of what was portrayed, while also foreseeing its fallout. Historical proximity was advanced through a jarring insider knowledge.

III

Rosemary Mitchell has described how the nineteenth-century understanding of the past was shaped through a ‘picturesque historiography’, in which the visual was as influential as the textual and a sense of empathy was considered an aid to insight.Footnote 32 Romantic in their outlook, picturesque histories dramatically reconstructed the colour and spectacle of past events, in turn, often blurring their nuances and complexities. The roots of this mode of historical imagination lie in the eighteenth century and one text, in particular, was influential in establishing a more accessible and emotive historical experience – David Hume's History of England (1754–62).Footnote 33 Indeed, Hume, himself, asserted that it was the responsibility of the historian to be ‘interesting’, to touch the reader and play upon their sympathies.Footnote 34 This effect was enhanced and extended when, in 1792, the miniaturist, Robert Bowyer, undertook to produce an illustrated edition of the History. More than a hundred pictures were painted (and subsequently engraved) to accompany scenes from Hume's narrative, spanning centuries of England's past.Footnote 35 In sympathy with the History's text, which was liberally interspersed with sentimental episodes from the lives of its protagonists, it was hoped that these images would serve to rouse ‘the passions, to fire the mind with emulation of heroic deeds, or to inspire it with detestation of criminal actions’.Footnote 36 Declaring the superiority of art in promoting an immediate historical experience, Bowyer remarked: ‘In many of those events, which strongly arrest the attention, there is some striking moment, the effect of which is unavoidably weakened by the mode of relating the tale…Here is the painter's advantage. What is done in an instant, his pencil as instantaneously tells.’Footnote 37 Bowyer's statement corresponds to a contemporary concern with the psychology of looking and the relationship between vision and the processing of knowledge.Footnote 38 His high-minded scheme ultimately led to his financial ruin.Footnote 39 Yet the resulting illustrations did much to create the scenery of English history, offering a body of images which later artists would repeatedly appropriate and adapt.Footnote 40

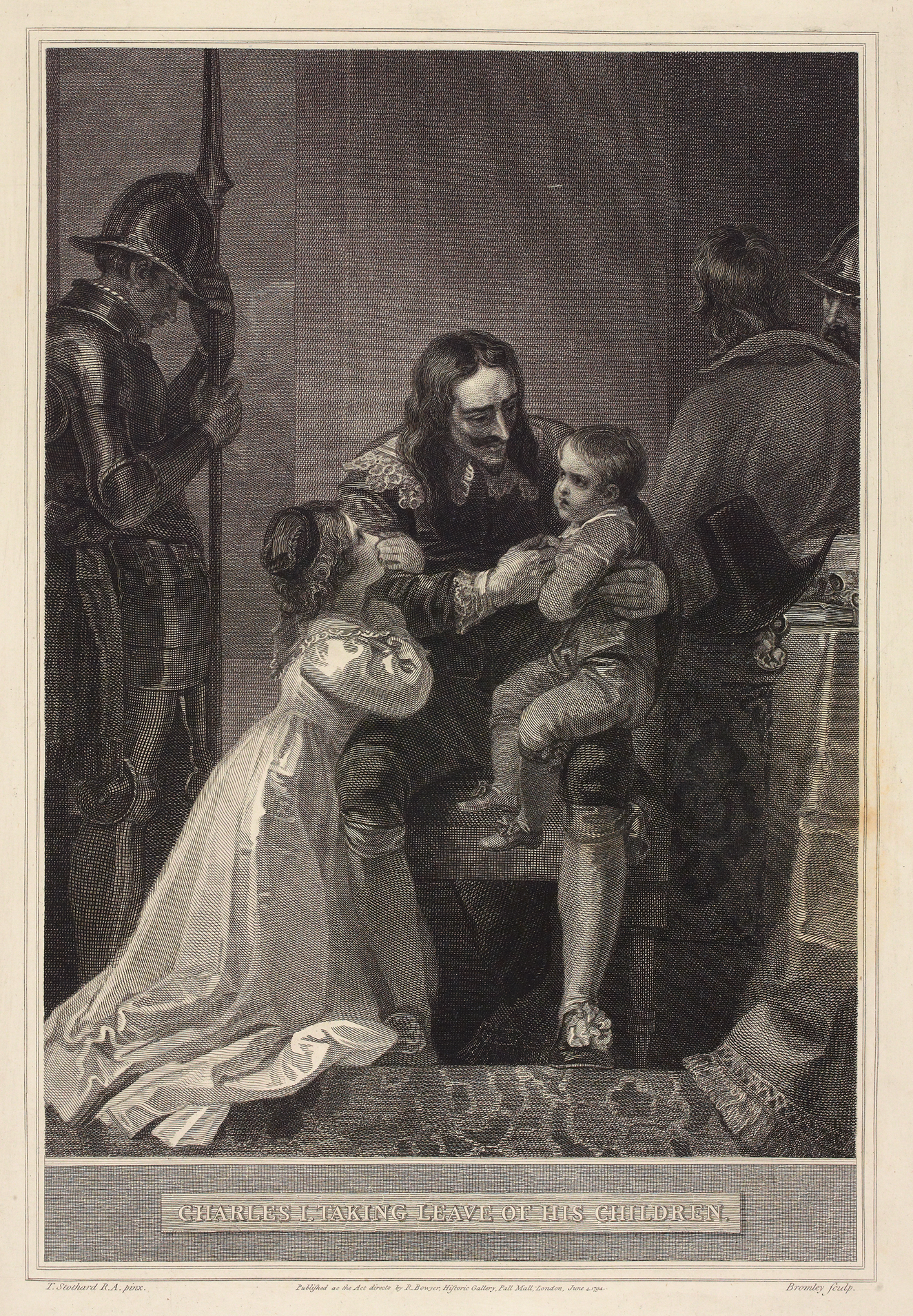

This coalition of text and image would also prove formative in the refashioning process to which the Caroline royal family would be subject, as is evident from Thomas Stothard's lost painting of Charles I taking leave of his children, commissioned for Bowyer's scheme and now known through engraved copies (1794, see Figure 5). Stothard's composition centres on the conversation between Charles and his youngest son, Henry, duke of Gloucester, the day before the king's execution – a moment described in the History as follows:

Holding him on his knee, he said, ‘Now they will cut off thy father's head.’ At these words the child looked very steadfastly upon him. ‘Mark child, what I say! They will cut off my head and perhaps make thee a king! But mark what I say! Thou must not be a king, as long as thy brothers, James and Charles are alive. They will cut off thy brothers’ heads when they catch them! And thy head too, they will cut off at last! Therefore I charge thee do not be made a king by them!’ The Duke, sighing, replied, ‘I will be torn in pieces first!’ So determined an answer from one of such tender years, filled the king's eyes with tears of joy and admiration.Footnote 41

Figure 5. William Bromley after Thomas Stothard, Charles I taking leave of his children, 1794. Engraving, 46.7 x 32.2 cm. David Hume, The history of England (folio edition) (10 vols., London, 1793–1806), X, L.C.Fol.36A(10), National Library of Scotland.

Hume's passage is virtually a direct quotation from the eye-witness account of Charles's daughter, Princess Elizabeth, which was first published just months after her father's death and frequently recited in biographies and histories thereafter.Footnote 42 Stothard's image too had a life beyond its inception, widely known not only through the extremely popular illustrated editions of Hume but also through later plagiarized copies, in books as diverse as W. H. S. Aubrey's The national and domestic history of England (1867) and Lady Calcott's Little Arthur's history of England (1856).Footnote 43 The family form a pyramidal arrangement, with a stubborn-looking, cross-armed Henry perched on his father's left knee and Elizabeth sprawled over his right, looking up attentively. In a rather neat adaptation of Van Dyck's ‘greate peece’, Elizabeth's figure has replaced that of the infant Prince Charles at the king's side, while the young duke, balanced on his father's lap, references Henrietta Maria's supporting embrace of the Princess Mary. The original patterns of connecting gestures and gazes have been condensed, converging on the figure of Charles. The dynastic and political intimations of the prototype have also been softened so that Charles no longer scrutinizes the viewer but instead focuses upon his son, wholly occupied with his careful instruction. Gone are the crown and regalia, replaced by the king's discarded hat, his Lesser George, and a book, presumably his Bible. This arrangement and the viewer's proximity to the picture plane create a sense of intimacy, heightened by the guard standing to the right of the family group, who bows his head in acknowledgment of his intrusion on this private meeting. Like him, the viewer is drawn in, sharing in the feeling of this parting. Stothard's composition then responded both to secondary textual and primary visual sources. The tragic scene which Hume had sketched in words was now realized in image. The artist's royal protagonist complemented the historian's ‘Poor King Charles’, courageous in adversity and morally upright to the last; a characterization designed to evoke a sympathetic reading.Footnote 44 Again, by quoting and adapting passages from Van Dyck's portraits, Stothard's painting formed a narrative with its pictorial prototypes. A sense of authenticity served as a bridge to the past, heightening the semblance of not only historical but also emotional truth. Visually emulating the sentimental voice of Hume, the pathos of the History's account was charged with immediacy.

The special relationship between word and image in Stothard's painting was characteristic of the nineteenth-century historical imagination. Written devices such as titles, quotations, and pictured words were frequently employed in order to instruct the public in the understanding of a picture.Footnote 45 Writing in 1843, as the first exhibition connected to the decoration of the new palace of Westminster opened, Sir Charles Eastlake described the daily multitude who came to view the cartoons illustrating subjects from British history or literature. As secretary of the commission responsible for the project, he had directed that an abridged catalogue be made available for a penny but found that ‘many of the most wretchedly dressed people prefer the six penny one with the quotations’.Footnote 46 It appears then that audiences appreciated this textual guidance that allowed them to read an image. Between 1801 and 1901, of the twenty-five paintings portraying the family of Charles I exhibited at the Royal Academy exhibitions, only three were not accompanied by a quotation or extended title.Footnote 47 Of those paintings supplemented by a quotation, one author's work appears to have held a special appeal – the historical writings of Agnes Strickland. The most prominent female historian of her time, Strickland's twelve volume series, Lives of the queens of England (1840–8), proved a great commercial success, as did her later works, which included biographies of the queens of Scotland and of Tudor and Stuart princesses.Footnote 48 Margaret Oliphant's commentary, written in 1855, which featured in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, provides an account of the position held by these books, both as literary works and as scions of popular culture:

Instead of a slow succession of elaborate volumes, full of style and pomp, accuracy and importance, it is a shower of pretty books in red and blue, gilded and illustrated, light and dainty and personal…It is not Edward Gibbon but Agnes Strickland – the literary woman of business, and not the antique man of study – who introduces familiarly to our households in these days the reduced pretensions of the historic muse.Footnote 49

Stressing the rapidity of production and the neat, gendered design of Strickland's books, Oliphant insinuates that as historical works they are both simplified and frivolous. Indeed, Strickland specialized in a form of whimsical historical biography that stylistically owed a significant debt to the romantic novel. Resisting the Whig interpretation of history, Agnes and her co-author and sister, Elizabeth, presented an alternative narrative, which was favourable to France, Catholicism, and the feminine.Footnote 50 Certainly, their analysis of Henrietta Maria figured her as a devoted wife, emphasizing her private virtues and generating ‘a sympathetic image of this much maligned queen’.Footnote 51 Like Hume, Strickland offered her readers ample opportunity to empathize with the predicaments of historical figures. Accordingly, one anonymous critic reviewing her Stuart volume of the Lives of the queens of England in the Edinburgh Review commented: ‘It would be endless to collect the innumerable passages in which she has exerted her ingenuity to cast an air of romance, of pathos, or of humour, over some pointless anecdote.’Footnote 52

The extent to which Strickland helped shape artistic representations of the family of Charles I can be seen by close examination of Charles Lucy's painting, The parting of Charles I with his two youngest children, the day previous to his execution (1850, see Figure 6).Footnote 53 The picture shows the king gazing upwards in torment, his head cradled in his hand, with his elbow propped against a window. Behind, Bishop Juxon and Princess Elizabeth cast pained glances in Charles's direction, each placing a comforting palm on the diminutive figure of the duke of Gloucester as they lead him away. An oval portrait of the absent mother, Henrietta Maria, presides over the scene. Meanwhile, just visible in the doorway, a soldier stands with his halberd ominously dissecting Van Dyck's portrait of Charles I at the hunt on the opposite wall. Comparison of the composition with Strickland's account of the last interview reveals the source for this arrangement: ‘The King fervently kissed and blessed his children and called to Bishop Juxon to take them away. The children sobbed aloud; the King leant his head against the window, trying to repress his tears.’Footnote 54 Indeed, when the painting was exhibited at the summer exhibition of the Royal Academy in 1850 it was accompanied by a quotation virtually identical.Footnote 55 Lucy's painting then is akin to a book illustration, so closely does it follow Strickland's text and tenor, expressing in visual form her retelling of the affectionate Stuart family whose ‘tears and caresses’ presaged its break-up.Footnote 56 A review by Dante Gabriel Rossetti provides a contemporary reaction to the canvas, elaborating on its sentimental allure:

The arrangement adopted by Mr. LUCY is simple and suggestive. Bishop JUXON, holding the young prince's hand, leads him out of the ante-chamber, where the sentry is posted, and where VANDYCK's portrait of the King has been left hanging; the princess now on the threshold, looks back at her father once more; while the quiet head and pattering shoe of the little boy, who is evidently trying to walk faster than he is able, and the delicate manner in which he is being led by the good bishop, are peculiarly happy in their sympathetic appeal. CHARLES, standing, raises one hand to his brow; his face is bewildered with anguish. He is turning unconsciously against the window and the hand which has just held those of his children for the last time, is quivering helpless to his side.Footnote 57

Figure 6. Charles Lucy, The parting of Charles I with his two youngest children, the day previous to his execution, 1850. Oil on canvas, 230 x 178 cm. Hartlepool Museum Service, UK © Hartlepool Museum Service /Bridgeman Images.

Extending Hume's sympathetic presentation of the past, Strickland's writing merged historical narrative with melodrama. In her account, the ‘pious consolations’ described by Hume became ‘a passion of tears’.Footnote 58 Similarly, instead of the quiet sentiment of Stothard's composition, Lucy's canvas resonates with feeling. Certainly, the review focuses on the emotional effects of the painting and on the interiority of its actors – the king's suffering, his daughter's concern, his son's guileless innocence. For Rossetti, the artist had eschewed the ‘mere parade of truthfulness’ and created a work of unmitigated veracity.Footnote 59 In both word and image, then, history has become domesticized, accentuating the intimate and affective; reducing and reinscribing the public and political. Again, the artist has made connections to seventeenth-century portrayals. Enlisting the original imagery in his story-telling, Lucy underscored the changed circumstances of the Stuarts and enhanced the scene's pathos. These nineteenth-century pictures and their counterparts then realized the changing tone of historical writing and comprised a visual historiography of the Caroline royal family. Materializing shifting historical perceptions, they sought to involve the viewer in moments of emotional poignancy. Conflating the borders between past and present, sympathy for distant suffering inspired a sense of historical proximity.

IV

Commenting on her contemporaries’ tendency to look back into history as a means of explaining the dilemmas of the present, Margaret Oliphant observed: ‘We recollect that these old heroes had not a thought of the nineteenth century under these grim visors of theirs, nor the smallest intention of benefiting us by their blunders and mischances, their breaking of heads and spears, their squabbles with kings and commons.’Footnote 60 Yet, despite Oliphant's caveat, the allure of the stricken Stuarts lay precisely in the apparent parallels between the fractures of the seventeenth century and the stresses which afflicted nineteenth-century society.Footnote 61 The aftershocks of the divisions of the Civil War ran deep and Victorian historical sympathies fell along contemporary political lines. Elaborating on this correlation, a reviewer from The Standard described an average audience at The Lyceum's 1872 staging of Charles I: ‘One third, it may be said were staunch Royalists, about a half were interested in the play and not in politics present or past…and only a small minority were devoted Liberals, jealous of every touch that seemed to blot the fair fame of the Radical idol [Cromwell].’Footnote 62 Playing upon this sense of historic communality, artists repeatedly reimagined the conflicts between Royalist and Roundhead as a pattern of the present which might also convey a revelation for the future. Resonances were compounded as the Caroline royal family was gradually subsumed into the Victorian cult of domesticity. Nineteenth-century family life was deemed more than a social institution; it was at the heart of civilized society.Footnote 63 The public were not only conscious of inheriting this fixation but actively sought out historical precedents for their own domestic cares.Footnote 64 The Caroline royal family provided one such precedent. The Stuarts had encouraged their subjects to take an interest in their family life, blurring boundaries between public and private and fostering affective ties between sovereign and subject.Footnote 65 Over two centuries later, their portraits continued to strike a chord. Stuart domestic messages were accepted, appreciated, and extended. In line with nineteenth-century models, Charles I became an affectionate and tender father, Henrietta Maria a supportive and obedient wife. Yet the unfortunate Stuarts had now become an object lesson, a conservative warning of the personal tragedies born of political unrest. This theme had been partially explored in the preceding century. Jean Raoux's painting of 1722, depicting the king's last meeting with his children, had been reproduced in a number of eighteenth-century British prints.Footnote 66 Nineteenth-century historical genre paintings, however, intensified this threat. Audiences were presented with a projection of their own home lives and encouraged to share in the trauma of domestic rupture. Artists exploited affinities and encouraged a strong identification with the past.

This partisan approach to history is palpable in Daniel Maclise's An interview between Charles I and Oliver Cromwell (1836, see Figure 7). The canvas depicts a fictional meeting between the king and the army's senior officers. Represented in profile, Cromwell is arrayed – rather implausibly – in full armour, with his scabbarded sword resting at his side. His likeness is loosely based on Robert Walker's portrait.Footnote 67 Cast as a figure of military might, he sits, shadowed, focusing his intense gaze on the royal captive. Behind him, Commissionary General Ireton, Cromwell's son-in-law, cups his chin in his hand as he records the proceedings, while the figure of Commander-in-Chief Thomas Fairfax emerges from the gloomy background. In contrast, the melancholic Charles (again closely modelled on Van Dyck's portraits) is illuminated; animals and children alike gather to his bosom. One hand rests on an opened and discarded letter, while his other arm sits on the shoulder of his son, who reads from the Bible. The chubby-faced, rosy-cheeked figure of Elizabeth snuggles into her pet dog, seemingly unaware of the import of the conference. This visual distinction between uneasy insight and artless innocence was identified by a contemporary critic, who observed that ‘the unconscious playfulness of the little prince and princess in their gay apparel, are [sic] well contrasted with the dejected looks and sombre habiliments of their unfortunate parent’.Footnote 68 In fact, the effect was carefully contrived. The appearance of the young prince, whom the artist identifies as James, duke of York, is drawn from Van Dyck's portrait of the seven-year-old second duke of Buckingham (1635, see Figure 8).Footnote 69 Maclise has even appropriated the red and gold clothing, which had been employed so strikingly in the original composition of the duke and his brother, adapting it for the dress of the prince and his sister. Elizabeth's likeness derives from an actual portrait of her as a toddler, contained within Van Dyck's The five eldest children of Charles I (1637, see Figure 9). James and Elizabeth, however, would have been around fifteen and thirteen years of age respectively during the king's negotiations with the army. Maclise has consciously infantilized this pair of princes, reinforcing their childish vulnerability and emphasizing the protective, nurturing role of their father. In this touching image of familial devotion, Charles has become a personification of benevolent paternalism. The artist's composition, then, visually contrasts two regimes and two forms of authority. Its black-and-white rendering of the past encouraged nineteenth-century audiences to see reflections on the canvas and to distinguish historical alignments.

Figure 7. Daniel Maclise, An interview between Charles I and Oliver Cromwell, 1836. Oil on canvas, 184 x 235 cm. Photo © National Gallery of Ireland NGI.1208.

Figure 8. Anthony van Dyck, George Villiers, second duke of Buckingham and Lord Francis Villiers, 1635. Oil on canvas, 186.7 x 137.2 cm. Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

Figure 9. Anthony van Dyck, The five eldest children of Charles I, 1637. Oil on canvas, 163.2 x 198.8 cm. Royal Collection Trust. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021.

The intensity of Cromwell's unreturned glare, caught in a moment of rumination, echoes the penetrating gaze contained in another historical genre painting. Paul Delaroche's depiction of a later episode in the interconnected histories of these two men, Cromwell and Charles I, pictured the regicide contemplating the lifeless body of the king.Footnote 70 The French artist was instrumental in promoting English Civil War subjects to an international audience and his influence on the development of the British school would be decisive.Footnote 71 He was working on his composition in 1830, when Maclise was in Paris, but it was also known through Louis Pierre Henriquel-Dupont's aquatint (c. 1833, see Figure 10).Footnote 72 Certainly, Oliver's boots and the chair upon which he sits in Maclise's picture owe a clear debt to its precursor. To the French viewer, Delaroche's painting was layered with historical parallels. Charles I could be read both as a portent of Louis XVI and of the more recently ousted Bourbon monarch, Charles X, while Cromwell suggested both Napoleon and the newly proclaimed king, Louis-Philippe.Footnote 73 It may well be that Maclise intended the searching, brooding gaze of his Cromwell to rhetorically prefigure Delaroche's conception of the last confrontation. A pictorial serialization of history is again apparent, a sequence of momentous episodes somehow connected. In adapting this motif, the composition opens a window into the interiority of the protagonists. However, whereas there is an intentional ambiguity to the French painter's representation of the final meeting, Maclise instead directs the understanding of the viewer. The extended quotation, which accompanied his canvas, when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition, hints at the futility of the negotiations and the incompatibility of these two ideologies: ‘After the surrender of Charles I from the Scottish camp to the English commissioners, many interviews took place between that prince and the leaders of the independent party, with a view to some final accommodation…They closed, finally, in a rejection by the king of the terms proposed.’Footnote 74 Maclise's self-penned passage stresses the breakdown of the talks, brought to an end by the king without settlement.Footnote 75 In his painting, Charles's later fate is inevitable and the monarch is figured as reconciled to his end. Martin Miesel has observed that visions of the ‘happy domesticity of the royal family, threatened with imminent disruption by cruel, venal and ambitious men, became the essential situation in the Tory Victorian version of the drama of King Charles’.Footnote 76 The widespread circulation in print of similar scenes ensured that this message extended beyond the crowds of the Royal Academy exhibitions.Footnote 77 Maclise was both a Tory and a royalist.Footnote 78 His composition warned of the dangers of radicalism, drawing attention to the family as innocent victims of this erosion of social harmony. Clearly delineating two opposing styles of governance, it exhorted audiences to view themselves in the imperilled Stuart domestic unit. The Caroline royal family was, therefore, charged with a potent symbolism, formed through a perceived relationship between subject and viewer. Historical proximity was enhanced by contemporary resonances within this unfolding drama, promoting affinity and rapport.

Figure 10. Louis Pierre Henriquel-Dupont after Paul Delaroche, Cromwell and Charles I, c. 1833. Aquatint, 43.3 x 55 cm. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

V

Writing in her journal during a stay in the Scottish Highlands in 1873, Queen Victoria mused: ‘Stuart blood is in my veins and I am now their representative and the people are as devoted and loyal to me as they were to that unhappy race.’Footnote 79 In reality, the queen's ancestral claims were a fiction; a rather inventive reading of British royal genealogy.Footnote 80 However, her statement indicates that the monarch shared with her subjects a deep connection to the Stuart past – a sense of direct inheritance. Indeed, when artists depicted the domestic happiness of Victoria and Albert or their growing brood, rich with allusions to Van Dyck, they pictorially augmented this claim to kinship. Like the Stuarts, however, the sentimental bliss of the Victorian royal family was carefully constructed.Footnote 81 Both the portraits of Anthony van Dyck and of Franz Xavier Winterhalter aspired to create a bond between royalty and the people – to bring the first family of the realm closer to their public. Nineteenth-century historical genre paintings of Charles I and his family were also designed to create proximity between viewer and subject, bridging the rifts between past and present. Historical distance diminished through a manifold visual experience. Artists and audiences strove to recapture, recreate, and relive the domestic bonds and fractures of the seventeenth century. They did so by drawing upon alignments and connections – temporal, visual, and verbal. These relationships were integral to the cognitive, emotional and associative responses of the viewer. Establishing an episodic narrative, these canvases initiated processes of recollection and recognition, they reflected sympathetic historiographies, and they encouraged a shared community with the pictorial protagonists. Historical proximity was engendered through a multi-layered visual encounter that was active and participatory. As Phillips has skilfully shown, all histories locate their audience in relation to the past. I have sought to contribute further dimensions to the understanding of historical positioning by mapping out how audience responses can coincide and converge to produce a familiarized past. Of course, this intimate view was also a distorted one. It was shaped with hindsight and coloured by nostalgia. Historical difference, as well as distance, was negotiated, moderated, and diminished to aid understanding. This was history as spectacle, an immediate but incomplete vision.

Competing interests

The author declares none.