The ‘calendar’ has evoked a particular meaning for Catholics since the 1930s. For those wishing to limit the size of their families, it indicates a ‘natural family planning’ method based on observation of the female cycle. Popularly referred to in this way, the Ogino–Knaus method gained approval from the 1930 encyclical Casti connubii, which, along with condemning abortion and divorce, explicitly forbade the use of ‘artificial’ contraception. The method, and Catholic doctrine on contraception as a whole, have caused heated debate in Poland, a chiefly Catholic country in which the church actively engages in debates about sexuality and has attempted to shape the reproductive behaviour of its congregation since before the Second World War.

In this article, we discuss Catholic teachings on family planning in Poland between the publication of Casti connubii and the mid-1950s, when the government legalized abortion and initiated a family planning campaign. Therefore, we cover three politically and socially distinct periods: the interwar period and the first ten years of communist rule, separated by a six-year war and occupation period when virtually all publication activity pertaining to family planning ceased. Rather than publication of the encyclical, it was secular debates about family planning and the endeavours of the social activist and literary critic Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński during the early 1930s that prompted Catholic reactions in Poland.Footnote 1 The legalization of abortion in 1956 and the ensuing birth control campaign also initiated wide debate, in which participants voiced their opinions on sexuality, ideal family size, gender roles, and reproductive politics.Footnote 2 Therefore, the period under study embraces the twenty-five years between two of the most crucial public debates on family planning in Polish history.

We argue that the period between 1930 and 1957 was coherent in terms of the content of Catholic teachings on family planning in Poland. The only distinguishable sub-period is the Stalinist era (1950–5), when, due to state repression, church publications drastically diminished, yet the content of Catholic teachings remained consistent and the Polish church maintained contacts with the Vatican.Footnote 3 We also show that, although there were some distinct national characteristics, the Polish debate and the teachings of the Catholic church on family planning resembled to a great extent developments in other countries, particularly in regard to visions of marriage and sexuality. As we delineate, by engaging in the discussion on family planning, Catholic authors in pre- and post-war Poland acted as constructors of modernity, construed in both periods in relation to nationalism.

As scholars of the intersection of religion and family planning have shown, national debates and receptions of Catholic doctrine formulated on the global level differed according to specific cultural context. Political and religious differences, for example, shaped the way Catholics responded to controversies on birth control.Footnote 4 Poland, as an eastern European, chiefly Catholic country, with a large Jewish minority in the interwar period, and in the post-war period more culturally and religiously homogenized, offers a unique perspective on the reception of Catholic doctrine. We also focus on the actors who shaped the church's stance on contraception, paying attention to transnational influences, which included transmission from the Vatican to the local church, as well as horizontal international circulation of writings. Nowadays in Poland, Catholicism still has a profound influence on legislation on issues such as abortion or LGBTQ+ rights. A comparative historical perspective may illuminate specific trajectories that shaped Polish Catholicism with its strong focus on reproduction.

Through an analysis of this reception and its specific features, we ask questions about the shaping of modernity by Catholicism in Poland. As recent scholarship on Great Britain and Ireland has shown, modernity was not only a challenge for religious doctrines by posing a threat of secularization, but was also being actively incorporated into those doctrines by Christians themselves.Footnote 5 Without engaging in theoretical debates on modernity, we understand modernization as a process of social transformation characterized by an increasing importance of scientific knowledge, technology, rationalism, and the belief in progress. From this perspective, we aim to analyse the relationship of science, religion, and modern nationalism in the Polish reception of Catholic doctrine on family planning.

To reconstruct Catholic teaching on family planning between 1930 and 1957, we examine relevant publications granted official approval by the Polish Catholic church hierarchy, paying particular attention to gendered dimensions, the emphasis placed on marriage and its objectives, and the ‘calendar’ method. For the post-war period, we also include two publications intended for use by priests in marriage preparation courses and lectures. These represent an early stage in this instruction, which underwent significant development from the mid-1960s onwards.Footnote 6 The question of the influence of these teachings on individual practice is beyond the scope of this article. As numerous studies have revealed, the influence of religion on reproductive decision-making is a complex process in which not only official doctrine and the clergy intervene, but also other actors such as the state and medical doctors.Footnote 7 By examining what kind of authors shaped Polish response to Casti connubii, we illuminate one of the dimensions of the complex reception and transmission process.

Our article builds on and dialogues with scholarship on Catholicism and family planning in the twentieth century, which has developed extensively in recent years, especially in relation to the West and Poland. Scholarly interest in Catholic teachings on contraception dates back to the 1960s and the seminal book Contraception: a history of its treatment by the Catholic theologians and canonists, by the American scholar John Tomas Noonan, the publication of which was prompted by debates on birth control by the Second Vatican Council.Footnote 8 In the ensuing decades, American historians addressed the birth control practices of Catholics and debate on contraception in American Catholic circles.Footnote 9 A similar interest in Catholic birth control doctrine and contraceptive practices spurred research and publications on developments in several largely Catholic Latin American and European countries.Footnote 10 Many historians studying more recent practices and discussions, particularly during the second half of the twentieth century, have relied extensively on oral histories to explore the intricate negotiations that lay Catholics have made with religious doctrine and the problems they have encountered when attempting to reconcile religious teachings with sexual desire.Footnote 11 Lastly, several new publications on Catholicism and contraception have adopted a transnational perspective, particularly when focusing on the 1968 encyclical Humanae vitae.Footnote 12 In contrast, the influence of and response to the Casti connubii encyclical has so far received little scholarly attention.Footnote 13 Lucia Pozzi's recent book and earlier articles have illuminated the process through which Casti connubii was produced and the response in a number of countries.Footnote 14 However, Catholic teachings on contraception stemming from the encyclical and their adaptation have not been studied in reference to predominately Catholic regions and countries beyond western Europe and North America.

Scholars interested in the engagement of the Catholic church in reproductive policies and practices in Poland have tended to focus on the post-1956 years.Footnote 15 The church's family planning policies of earlier decades remain under-researched. When examining issues related to family planning in the 1930s, scholars have mostly concentrated on the activities of those engaged in the ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign, and have rarely subjected the teachings of the Catholic church to systematic scrutiny.Footnote 16 Scholarship devoted to reproductive politics in the early years after the Second World War has emphasized population policies and abortion legislation.Footnote 17 The role of the Catholic church and its teachings on family planning in this period have yet to receive thorough analysis.

In what follows, we first establish the main premises of reproductive politics in interwar and post-war Poland. We then explore the major Catholic publications on family planning of the period, first discussing their content and authorship, and then focusing on three themes that were most prominent in the advice books and pamphlets we have analysed: the framing of the ‘calendar’ method in terms of goals and usage; how the objectives of marriage were construed in the context of procreation and the conceptualization of gender roles; and the ideal family size advocated by Catholic writers, and their underlying arguments.

I

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Poland was a predominantly agricultural country characterized by high rates of both fertility and infant mortality. Revived in 1918 after over a century of partitions, the Polish state retained three separate sets of inherited legislation during the first decade of its existence. At the beginning of the 1930s, as a Codification Committee attempted to unify the law, a heated debate was initiated on the issue of abortion. One argument employed by proponents of liberal abortion legislation was the need to reduce the high number of clandestine abortions through the provision of information about contraception. While abortion was illegal in interwar Poland, in contrast to several Western countries such as France and the United States, contraceptives and their promotion were not prohibited.Footnote 18

In the wake of this discussion, two groups began to campaign for birth control: one consisted of liberal writers and literary critics associated with the magazine Literary News (Wiadomości Literackie); the other was a group of socialist doctors and activists. Referring to the idea and practice of family planning as ‘conscious motherhood’, these liberals and socialists included articles on family planning in their periodicals and established a number of birth control clinics, mainly in the larger cities, to advise women on female-controlled methods of contraception. Although the campaign for conscious motherhood engaged several doctors and social activists, the Polish public primarily associated it with one person: the literary critic and writer Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, who, during the 1930s, was vehemently criticized by opponents of family planning and sexual reform.Footnote 19 Some of his most vocal adversaries were recruited from the Catholic clergy, and condemnation of conscious motherhood by the powerful and influential Catholic church certainly contributed to the demise and lack of lasting impact of Polish birth control activism in the mid-1930s.

The December 1930 publication of Casti connubii prompted significant interest among the church hierarchy and the Polish public.Footnote 20 The encyclical responded to the liberal stances on contraception recently adopted by some Protestant churches,Footnote 21 but, in a broader sense, the document was a reaction to increasingly secular trends in attitudes to sexuality, embodied in the highly popular book by Theodor van de Velde, Ideal marriage.Footnote 22 Casti connubii was swiftly translated into Polish and published in the midst of the aforementioned conscious motherhood debate.Footnote 23 It was followed by a cascade of publications intended to popularize the church's reproductive doctrine and its practical consequences. Publications by Catholic authors were set in ‘a confronting dialogue’ with the opinions and views of liberal and socialist doctors and activists engaged in the conscious motherhood campaign, particularly those of Boy-Żeleński.Footnote 24 Consequently, while Polish authors of booklets on Catholic teachings in the 1930s only mentioned Casti connubii intermittently, they almost always discussed the activities of these domestic birth control pioneers. This Polish Catholic discourse was, therefore, a reaction to its secular equivalent, in parallel with an encyclical that responded to secular trends on a global level.

The war that began in Polish lands in 1939 decimated the population. As the historian Barbara Klich-Kluczewska has argued, the aim of post-war population policies was to ‘make up for the losses of war’ in a country that had lost ten million people through war-related deaths, mass migrations, and border changes. The communist authorities responded to this phenomenon with pro-natalist propaganda, criticism of neo-Malthusianism, and policies intended to strengthen the post-war ‘baby boom’. Providing insured families with benefits, the socialist state limited access to abortion and contraceptives – not manufactured in the centrally planned economy – and medicalized pregnancy and childbirth, enhancing pre- and neo-natal care in an attempt to reduce infant mortality.Footnote 25 While the Catholic church was often at odds with the communist government and suffered a significant blow to its political influence, particularly under Stalinism, it applauded these pro-natalist policies.

The post-war baby boom, the reduction in infant mortality, and state pro-natalist policies resulted in a sharp rise in the birth rate during the early 1950s. In response to this, as well as to a shift in Soviet population policies, which included the legalization of abortion in 1955, and concern about the ability to satisfy the consumption needs of an increasing population, Polish authorities adopted a policy of moderate anti-natalism in the mid-1950s. Abortion was legalized in the country in 1956 and a birth control campaign was launched the following year. The Catholic church, the influence of which increased during the post-Stalinist political thaw, actively participated in the debate unfolding in the wake of changes in reproductive and population policy.Footnote 26 Vehemently critical of both abortion and ‘artificial’ contraception, the church was still advocating the teachings of Casti connubii in the mid-1950s.

II

In this section, we discuss the characteristics of Catholic writings on marriage and family planning, paying particular attention to authorship and transnational influences. The so-called Ogino–Knaus method advised in Catholic books and pamphlets was discovered in the 1920s independently by a Japanese gynaecologist Kyusako Ogino and an Austrian gynaecologist Hermann Knaus. It was then adopted and popularized in the 1930s by the Dutch Catholic physician Jan Nikolaus Smulders.Footnote 27 During the period under discussion, however, there was no official Catholic recommendation of this method: rather, the 1930 papal encyclical was construed as approving natural birth regulation. In order to ensure readers that their publications followed church teachings, books on the Ogino–Knaus method contained an imprimatur (from Latin, ‘let it be printed’) – a declaration of church authorization. There was some opposition to the method within the Catholic church in Poland during the 1930s, particularly from older conservative theologians and nationalists. However, a substantial number of liberal theologians approved of both the method and the interpretation of Catholic teachings on marriage presented by authors of these publications.Footnote 28

Some of the publications focused on the theological dimensions of marriage, while others concentrated on how to apply the Ogino–Knaus method. Many contained tables for calculating fertile and infertile periods and other practical information to enable Catholic couples to use the ‘calendar’ method without professional medical instruction. During both the 1930s and the post-1945 period, Catholic authors tended to refer to their subject matter as ‘periodic abstinence’ (wstrzemięźliwość okresowa) or ‘natural regulation of births’ (naturalna regulacja urodzeń), thus avoiding the terms adopted by the birth control movement in Poland and abroad, such as ‘birth control’ and ‘conscious motherhood’, although in some instances Catholic authors attempted to redefine the latter in Catholic terms.Footnote 29

Advice books and pamphlets were intended for either married couples or fiancés in the process of marriage preparation. Some responded to the encyclical call to organize marriage preparation for Catholics, providing a concise résumé of the doctrine to be distributed among fiancés, who would then undergo a pre-marital exam.Footnote 30 Some were explicitly targeted at a broader Catholic public, including physicians, priests, mothers, and fathers.Footnote 31 Their content informed Catholic laity, either directly or indirectly, intermediated by Catholic clergy. However, the readership of particular titles is difficult to trace, even if references to them might be found in memoirs of the post-war generation.Footnote 32

With one exception, all advice books and pamphlets were written by men – priests and Catholic intellectuals – and most were produced by Catholic publishing houses.Footnote 33 Medical doctors were less well represented, in contrast to the prominent role played by Catholic doctors in developing and explaining the church's doctrine on birth control, or shaping reproductive practices, in other countries, both pre- and post-war.Footnote 34 Among the analysed authors, only one – Aleksander Zajdlicz – presented himself as a ‘doctor’, nevertheless hiding behind a pseudonym. Other authors did not build their authority on professional medical knowledge, but rather as Catholic clergy or just ‘Catholics’. Medical doctors were present as supporting actors, as in the case of Polish editions of the German-language pamphlet by Iwan Eugen Georg, to which a preface was written by a Polish doctor, Paweł Gantkowski. Gantkowski was the author of a textbook on ‘pastoral medicine’, where he explained hygiene and medicine to Catholic priests. In the chapter devoted to procreation, he gave advice to confessors how to understand women's confessions of abortion, usually referred to by a range of euphemisms, as well as highlighted that – according to medical knowledge – ‘life begins at conception’.Footnote 35 As this example shows, Catholic medical doctors played a role in the shaping of Polish priests’ knowledge on human reproduction and advice on moral judgement, yet when it came to propagating the ‘natural regulation of birth’, priests were at the forefront. Medical authority, however, was often invoked. An interesting case is Walenty Majdański, a prolific author of anti-abortion pamphlets, who was not a doctor but sometimes published under the name ‘doctor Antoni Henke’, thus claiming medical authority.

Catholic publications on family planning included works by Polish authors but also numerous translations, mostly from German. The most popular foreign publication on the Ogino–Knaus method translated into Polish was a book by Iwan Eugen Georg, which was the nom de plume of a probably Austrian, or Czech, enthusiast of the Ogino–Knaus method.Footnote 36 This work had six Polish-language editions between 1935 and 1949, being reissued three times in the pre-war years and the same number of times in the post-war period. The book became a global phenomenon, translated in the 1930s and in post-war decades into several languages, and published widely in Europe and the United States. Polish Catholicism, therefore, remained transnationally connected both before and after the Second World War, despite the communist takeover in 1945. Nevertheless, some Polish authors felt mobilized by this transmission to provide ‘a Polish product to substitute the foreign ones’, written by a ‘Polish citizen’.Footnote 37 The apparent disapproval of the popularity of the German language translation did not, however, stem from its possible connotations with Nazi Germany, as the circulation of Georg's book encountered obstacles in Germany, which in the post-1933 period based its reproductive and population policies on eugenic principles. Nazi eugenic policies entailed not only sterilization of the ‘unfit’ but also a ban on contraceptives for those who might produce ‘quality children’.Footnote 38 As Georg declared in the preface published in the post-war Polish translation, his book was outright banned in Austria after 1938 German annexation, which shows that the Nazis interpreted Georg's publication as a possible incentive to and a tool for limiting births.Footnote 39

Another important foreign publication on natural regulation of births that circulated in Poland was Natural birth control, written by a progressive-liberal American priest, John O'Brien. Published in the United States first as a booklet entitled Legitimate birth control, it was issued in 1938 in an extended version with tables and instructions explaining in detail how to implement the Ogino–Knaus method.Footnote 40 The book was translated and published in Polish in 1949 by a secular publisher without official church approval. What linked O'Brien's publication with several local Polish productions was the emphasis on practical use of the ‘calendar’ method, and his references to science that was to legitimize the method's usage and that was embedded in the discourse of modernity.

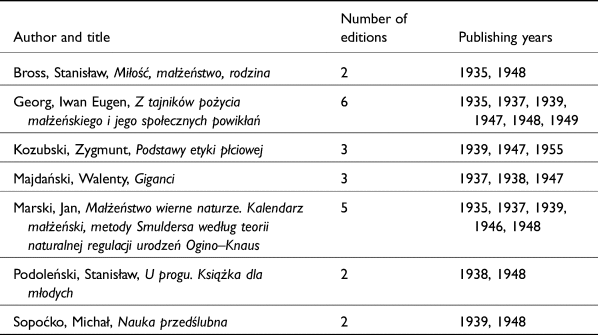

A large number of 1930s publications were reprinted several times during the pre-war decade and republished in the post-1945 years. We observe a strong continuity in terms of published titles and authors, such as Georg, although some authors were popular either before the war, like Aleksander Zajdlicz (the pseudonym of Andrzej Niesiołowski), or after, such as Majdański, who first published in 1937 and authored four titles in the post-war period (see table 1). About thirty publications were produced between 1945 and 1949, and only five during the Stalinist era. Although the content of the publications remained generally the same in different editions, the authors frequently changed the introductions or prefaces, reacting at times to the discussions developing in relation to the book's publication, or providing additional rationales for the method.

Table 1 Polish books on natural regulation of births with multiple editions

III

In this section we discuss the framing of the ‘calendar’ method, the rationale of and implementation of which was the most prominent theme in the publications we have explored. Examining the goals of the Ogino–Knaus method discussed by the Catholic authors, as well as its practical usage, we emphasize continuities in the pre- and post-war periods, and we juxtapose the Catholic teachings on family planning with those of the liberal and socialist proponents of ‘conscious motherhood’ in the interwar period.

Polish Catholic publications, in line with church doctrine shaped by Casti connubii, discouraged the use of both abortion and contraception as birth control. Artificial contraception was conceptualized in the encyclical as ‘abuse’, a term employed since the nineteenth century to mean improper use of the conjugal act.Footnote 41 Drawing on encyclical recognition of the right to sexual restraint in marriage, Catholic authors propagated birth control methods that could be interpreted as legitimate in light of Holy See teachings. While the encyclical did not explicitly authorize calendar-based methods, and papal approval was not given until a speech to midwives in 1951, using knowledge of female physiology discovered in the nineteenth century had never been officially condemned.

In line with Casti connubii, Polish Catholic authors unanimously condemned contraception. In direct references to the encyclical, using ‘artificial methods of avoiding conception’ was labelled abusus matrimonii and ‘against nature’.Footnote 42 The rationale against contraception included both moral and medical arguments. It was claimed that using contraception placed women's health in danger and could lead to sexual disorders.Footnote 43 Abortion caused even greater damage. Both practices were considered sinful. Advice books stated that undergoing abortion would produce ‘immediate punishment’, such as infertility, disease, or even death. Catholic authors also denounced another popular way of avoiding pregnancy, coitus interruptus, as unhealthy for women.

In their disapproval of artificial contraception, Polish Catholic authors followed the line established by the church but differed from the liberal and socialist proponents of ‘conscious motherhood’ in interwar Poland. Doctors and activists engaged in the family planning campaign advised women on using female-controlled barrier methods such as diaphragms that would be disapprovingly deemed ‘artificial’ by the Catholic authors. Liberal birth control pioneers discouraged coitus interruptus as too taxing on the nerves and unreliable, in which they resembled Catholic authors.Footnote 44 A socialist social activist and doctor, Justyna Budzińska-Tylicka, while identifying some similarities in the rationales of Catholic authors discussing the calendar and the arguments of birth control pioneers (discussed in the following sections), differentiated strongly between the Ogino–Knaus method and the ones advised in birth control clinics, stressing the unreliability of the former.Footnote 45 At the same time, Catholic authors and enthusiasts of ‘conscious motherhood’ converged in their views regarding abortion, envisaged as an improper and harmful way of controlling fertility.Footnote 46

The Ogino–Knaus method of establishing fertile and infertile periods was the sole method of natural birth regulation presented in Polish Catholic publications during the period under analysis. Polish authors did not refer to a natural family planning method that relied on measuring temperature to establish fertile and infertile periods, established in the mid-1930s. The publications usually recommended the ‘calendar’ method developed by Smulders, transferred to Poland through translations of foreign publications, particularly from German, in an example of transnational knowledge transfer and adaptation of foreign publications to the Polish audience.

Both pre- and post-war publications characterized the ‘calendar’ method in a consistent way, emphasizing its morality, usability, and reliability. The Ogino–Knaus method was presented as a healthy and moral alternative to contraceptives, coitus interruptus, and abortion, enabling married couples to enjoy sex and therefore cultivate the secondary objectives of marriage (such as mutual assistance) without resorting to immoral and damaging methods.Footnote 47 Periodic abstinence, as some authors emphasized, helped strengthen a person's moral qualities. The Ogino–Knaus method involved ‘using nature’ rather than abusing it, benefiting from the natural infertility periods generously granted by God.Footnote 48 The juxtaposition between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ was consistently used in Catholic publications on contraception, as it highlighted the negative nature of ‘artificial birth control’ as violating natural law. Present in Catholic discourse since the late nineteenth century, it was later applied in the 1968 encyclical Humanae vitae, reinforcing the ban on ‘artificial’ contraception after the invention of the pill.Footnote 49

Advice books of the 1930s often presented the method as a simple technique not requiring medical advice.Footnote 50 Publications intended to be practical manuals used in the privacy of home included calendars and elaborate explanations of how to count fertile and infertile days. While some authors officially stated that medical consultation could help in establishing these days, they acknowledged that only a few doctors were acquainted with the method and that Catholic practitioners could rely on their own observations and careful practice.Footnote 51 This supposition differentiated Catholic publications from statements by interwar birth control pioneers in Poland and elsewhere, who insisted that contraceptive advice should ideally be provided by doctors in birth control clinics.Footnote 52 Doctors played a salient role in the interwar ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign in Poland, legitimizing the provision of contraceptive advice.Footnote 53 In contrast, the milieu of Catholic proponents of natural regulation of births relied at large on priests and lay authors without medical training. In comparison to other countries such as Switzerland, in Poland Catholic doctors did not become widely involved in propagating the method, in either the pre- or post-war period.Footnote 54 This very limited engagement of medical practitioners in Polish efforts to spread information about ‘natural regulation of births’ may have stemmed from the Catholic church's attempts to retain control over the teaching of the method. Only after 1956 and the liberalization of the abortion law did Catholic doctors and nurses became more thoroughly involved in Catholic preparation for marriage that entailed teaching on ‘natural regulation’.Footnote 55

The Ogino–Knaus method was presented as reliable due to its ‘scientific’ nature, with scientific knowledge being identified as one of the salient components of modernity. To emphasize the rationality of the entire Catholic system of fertility regulation, depictions of the method as an ‘accomplishment of science’ regularly appeared in pre-war Catholic publications.Footnote 56 In the new communist political reality of the post-war years, Catholic advice books continued to present the Ogino–Knaus method as a scientific achievement, and users as modern Catholics, claiming that the technique facilitated realization of the ‘rational fertility’ endorsed by both science and religion.Footnote 57 Both pre- and post-war Catholic teachings also emphasized the health of the mother, whose well-being might be endangered by too frequent pregnancies.Footnote 58 Economic arguments were particularly convincing during the Great Depression.Footnote 59 As one author argued in 1937, ‘today's economic system does not allow for feeding numerous offspring’.Footnote 60 Another prominent set of rationales referred to population issues and eugenics, discussed below in the section on family size.

IV

In this section, we explore conceptualizations of the objectives of marriage by Catholic authors, juxtaposing them with a broader discussion pertaining to (marital) sexuality that was taking place in Poland particularly in the pre-war years, in the milieus of liberal and socialist proponents of ‘conscious motherhood’. The gradual reconfiguration of sexuality in marriage, triggered by modern sexology and already present in Christian discourses in the 1920s, was also connected to a rethinking of gender roles and gender equality.Footnote 61 Therefore, in the latter part of this section, we discuss how Polish Catholic discourse in the 1930s addressed women's and men's roles, and ideals relating to femininity and masculinity.

As Lucia Pozzi has shown, the twentieth-century detachment of sex from reproduction arose in relation to modern and secular perceptions of sexuality: perceptions that the encyclical Casti connubii was intended to combat. To counter the notion of sex as an autonomous sphere, increasingly present in secular literature, the Holy Office advocated a materialist approach to marriage – marital union equalled reproduction – that persisted until the Second Vatican Council.Footnote 62 However, the encyclical also referred to secondary objectives:

For in matrimony as well as in the use of matrimonial rights there are also secondary ends, such as mutual aid, the cultivating of mutual love, and the quieting of concupiscence which husband and wife are not forbidden to consider as long as they are subordinated to the primary end and so long as the intrinsic nature of the act is preserved.Footnote 63

Building on this distinction, Polish publications recognized the role of sexuality beyond procreation and, to some extent, praised marital eroticism.

Catholic authors of books published in Poland in the pre- and post-war periods discussed the objectives of marriage at length. Although Catholic priests and thinkers emphasized that the primary aim of marriage was reproduction, they also acknowledged the forming of a marital bond, unity, and mutual assistance. The secondary objectives of marriage, these authors insisted, constituted why Catholic couples should employ church-approved fertility regulation.

The primary aim of marriage was framed as ‘giving life’, and the purpose of sexuality was to serve this goal. ‘Eroticism/sexuality in marriage is blessed as a source of new life’, stated Zygmunt Baranowski.Footnote 64 While the birth of children strengthened marital bonds, reproduction enabled marriage to fulfil its social role.Footnote 65 Several pre-war Catholic booklets published in Poland recognized the importance of sex in the development of marital unity.Footnote 66 Georg declared that the experience of forming ‘one body’ during sex was important for strengthening the marital bond.Footnote 67 Catholic authors agreed that complete abstinence should be the choice of priests, not couples.Footnote 68 Zajdlicz, underscoring that marital sex was the only possibility for Catholics to satisfy their sexual desire, placed considerable emphasis on the other objectives of marriage such as providing mutual aid and solace, aims also emphasized in other interwar publications.Footnote 69 Such a framing of marriage objectives and the stress that Zajdlicz put on marital sexual satisfaction sparked reactions from liberal and socialist proponents of birth control, engaged in interwar Poland in the ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign. Boy-Żeleński and Budzińska-Tylicka, whom Zajdlicz directly mentioned in the first edition of his publication, highlighted the congruity between The discovery of Dr Ogino and liberal and socialist stances on the role of sex in marriage.Footnote 70 In this acknowledgement of the importance of sex in creating and maintaining the marital bond, Catholic authors such as Zajdlicz resembled liberal and socialist activists and journalists.Footnote 71 Such a stance was also visible in publications of foreign authors connected to the Protestant or reformist milieus and denominations, some of which eased their position on contraception prior to the publication of Casti connubii, referring among other things to marital sexuality in their rationales.Footnote 72 As argued by Laura Ramsay, new, more positive approaches to sexuality had already emerged among Christians in Britain in the early 1920s, when old traditional norms were revised in the light of new sexological knowledge.Footnote 73

These teachings persisted in the post-war period. Some authors stressed that the role of sex in marriage was not limited to conception, but was also a means of ‘mutual devotion’ (wzajemne oddanie). Jan Marski claimed that sexual intercourse in marriage could never be ‘something sinful’ as it was an expression of love.Footnote 74 O'Brien explicitly depicted marital sexuality as a source of happiness. As ‘permanent abstinence’ was harmful for marriage, an unbearable burden on Catholics, and could have negative psychological consequences, married couples should not abstain from sex when attempting to prevent conception.Footnote 75 In addition, O'Brien elaborated extensively on the contention that sperm was beneficial for the female body, linking theological and medical arguments in a seemingly scientific claim also employed by other authors.Footnote 76 According to O'Brien, women's physical and mental health depended on sexual intercourse.Footnote 77 The value given to sexuality by these Catholic writers went beyond the framing of marital sexuality as a remedy for sexual desire.

Discussions on sexuality, marriage, and family planning in Catholic publications also reveal the authors’ beliefs about gender. As Pozzi has discussed, feminism and the idea of gender equality were condemned in Casti connubii in an attempt to restore traditional values. The notion of women's rights had not only inspired birth control but also went ‘hand in hand with the new conception of sexuality’.Footnote 78 However, portrayals of femininity and masculinity in advice books were far more multifaceted, particularly in reference to marital sexual pleasure.

In Polish Catholic advice literature, women were depicted as naturally maternal, ready to sacrifice themselves for their offspring even before a child was born. Descriptions of somatic and mental disorders among childless women were often included to illustrate the unnatural and unhealthy essence of such a condition. However, women were also sexual beings and should enjoy marital sexual relations. With the exception of one author, who viewed wifely sexual duty as a burden, the majority of authors emphasized the need for both men and women to experience sexual pleasure.Footnote 79 ‘Both spouses have equal right to sexual intercourse’, declared Michał Sopoćko.Footnote 80 Georg stated that mutual pleasure was important and that a husband's role was to provide his wife with sexual satisfaction.Footnote 81 Pre-marital course materials from the early 1950s comprehensively explained that men ‘should not be violent but tender and loving, otherwise sexual acts could provoke disgust and fear in women’.Footnote 82 Sexual intercourse was therefore not seen as a mere biological need, but the right of both spouses.

Catholic authors rejected double standards in relation to pre-marital sexuality, demanding ‘chastity’ from both men and women.Footnote 83 Equality of demands for both sexes had been promoted by Christian feminists since the early twentieth century.Footnote 84 This premise was demonstrated in publications discussing ideal masculinity, which promoted a model of Catholic manhood based on self-restraint, strong will, and care of women.Footnote 85 These qualities, required to practise natural regulation of births, resemble the masculinity promoted in Britain as part of the ‘culture of abstinence’, in which self-control was regarded as the proper way to limit births.Footnote 86 The stress on self-restraint was also present in religious teachings in several other countries and settings. As argued by Anne-Françoise Praz, Protestant religious discourses in early twentieth-century Switzerland specifically targeted men, prompting them to change their sexual behaviour and to practise the self-restraint necessary to limit children and to attain the new model of a good father and husband. In contrast, Catholic discourses did not directly address men and ‘supported the husband's right to frequent sexual intercourse’, inciting men to produce many children.Footnote 87 The discrepancy between Protestant and Catholic teachings probably diminished after 1930, when the publication of Casti connubii led to the development of the model of masculinity promoted in the publications of Polish Catholic authors, whose inspiration might have been the ideals promoted by Protestant priests and sex reformers.

Apparently, women, with their less significant sexual appetites, did not need to develop such qualities as self-restraint or strong will. This conviction had appeared in Catholic family planning literature as early as the 1930s, when one publication asserted that ‘women agree more willingly to periodic abstinence’. Men supposedly preferred to resort to artificial contraception or even abortion rather than periodically abstain from sex.Footnote 88 Periodic abstinence using the ‘calendar’ method was therefore also intended to protect women from male sexual appetites.

This conservative model of femininity that stressed self-sacrifice and sexual passivity of women differed significantly from the ideals applauded by liberal and socialist enthusiasts of ‘conscious motherhood’ in interwar Poland. They envisaged birth control as a tool to change the position of women in the family and in society, leading to the evolution of the family from a patriarchal model to a modern one characterized by equal relations between spouses. According to the proponents of ‘conscious motherhood’, the ability to limit the number of children was seen as a prerequisite of women's emancipation and equality, as well as sexual satisfaction, much in line with the ideals of interwar Western sexual reformers, whose ideas Polish pioneers of birth control applauded.Footnote 89

As previously mentioned, arguments in favour of natural birth control prioritized the health of women. Moreover, in contrast to discourses recommending total abstinence, because the rhythm method relied on self-awareness and self-observation, female physiology was placed centre-stage. This may have contributed to a shift in the perception of women's roles in the transmission of Catholic teachings. During the 1930s and 1940s, Catholic discourse on family planning in Poland was almost exclusively produced by men. However, in the second half of the 1940s, Majdański began to write about the special role Catholic women should take in promoting the rhythm method. He suggested that lay Catholic women, and professionals such as teachers and medical doctors in particular, should come together to create ‘a big organization’ known as the Women's Social Service.Footnote 90 Pre-marital course materials elaborated in Warsaw during the early 1950s included a section written by an anonymous female doctor, demonstrating the increasing role of lay women in the institutionalized transmission of Catholic teachings.Footnote 91 In the ensuing decades, particularly after the debates in 1956–7, women became important actors in the shaping of Catholic instruction of natural birth control in Poland.

As we have stressed in this section, a visible similarity regarding the objectives of marriage as well as gender roles and models characterized pre- and post-war Polish Catholic publications on family planning. In their emphasis on the role of sex in creating a marital bond, as well as in the promoted ideals of masculinity, Catholic authors encouraged ideals resembling those endorsed in Catholic – and at times Protestant – milieus in other countries, but they were at odds with the visions of family and femininity applauded by Polish birth control pioneers. In the framing of marital sexuality, Catholic authors resorted to modern medical arguments, merging them with moral premises.

V

In this section we discuss the ideal family size promoted by Catholic writers and examine the similarities and dissimilarities in supporting arguments used in the interwar and post-war periods. Our particular interest lies in population-related arguments delineated in publications, their connection to eugenic and nationalist framing, and changes due to war losses and the need to rebuild the population.

Throughout the period under study, the ideal family size advocated by the authors of Catholic advice books was four or five children. Majdański described this as a ‘rational large family’, a balance between uncontrolled procreation and a small family with one or two children.Footnote 92 ‘Irrational’ procreation was deemed unhealthy and damaging for marital relationships: as the priest Zygmunt Baranowski, author of three books on marriage in the late 1940s, phrased it, ‘one shouldn't beget (płodzić) children without thinking’.Footnote 93 In the 1930s, Zajdlicz emphasized that ‘blind’ or ‘mechanical’ fertility should be replaced with ‘conscious’ reproduction, enabling Catholics to ‘fulfil their duty’ to God and the nation.Footnote 94 Catholic authors urged readers to combine ‘nature’ – a positive attitude to fertility – with ‘culture’, understood as knowledge and rationality.Footnote 95

Authors also presented a range of arguments for having more than two children, the number that particularly predominated among middle-class families and the intelligentsia in the interwar era. Stanisław Bross, author of a pamphlet entitled Love, marriage and the family, published in 1935 and 1948, argued that mothers had ‘enough love’ for many children, and that reproducing was a duty ‘to the state and humanity’.Footnote 96 A large family therefore complied with both the law of nature – identified in Catholic writing with the ‘laws of God’ – and social duty.

These publications also linked limiting family size to maternal and child health. Georg argued that giving birth too often endangered women's health, while a marriage preparation script by an anonymous author recommended not bearing children more frequently than every other year.Footnote 97 According to Georg, four to five children made it possible to have a ‘normal’, healthy family while also guaranteeing ‘constant population growth’.Footnote 98 In discourses about ideal family size, rationality, cultural behaviour, normalcy, morality, and health were the key arguments for ‘regulating births’.

As already mentioned, Catholic authors considered having a large family to be the fulfilment of not only religious but also national duty, therefore having to navigate between the recognition of the need to control fertility and ideas of national strength lying in population numbers, especially where compared to real or perceived enemies. In the pre-war years, Catholic proponents of families with four or five children expressed diverse stances on demographic issues. Living in a country characterized by high birth rates, one author perceived periodic abstinence as a way to prevent ‘overpopulation’ in Poland.Footnote 99 Zajdlicz, however, believed that families having fewer than five children would reduce the population.Footnote 100 Marski, in both pre-war and post-war editions of his Marriage faithful to nature, argued that he did not aim to reduce the number of children born to a family, because that would mean ‘a great social mistake’, since only a large family serves the state because ‘imperial power’ lies in the families. Poland – he claimed – was facing a population decline, ‘which might soon become a danger for our future’.Footnote 101 The pre-war edition contained an appendix with quotations from the press which clearly pointed to population threats from the German and Jewish populations. Germany was portrayed as a nation that was increasing population-wise, while the Jewish minority in Poland was suspected of promoting birth control in order to weaken Polish Christians. This understanding could have been triggered by a more general idea of Polishness as closely related to Catholicism, promoted by right-wing politicians and part of the episcopate since the early twentieth century.Footnote 102

In the post-war edition, this appendix was logically excluded, but Marski added that rational birth control would ‘help rebuild the country devastated by war’, and preserved the general view that the nation's strength lay in demography.Footnote 103 The pre- and post-war editions of the book on marriage preparation by the priest Michał Sopoćko included the same paragraphs depicting motherhood as women's ‘military service’ to the nation. The post-war edition, nevertheless, was considerably revised, and the author put even more stress on large families and on the indissolubility of marriage.Footnote 104 Interestingly, Sopoćko did not allude in these writings to the image of Poland as having an exceptional mission for Christianity, which he was developing in his efforts to spread the cult of Divine Mercy from the 1930s.Footnote 105 Several other post-1945 publications emphasized the demographic problems faced by Poland. Zygmunt Baranowski, for instance, warned that ‘avoiding pregnancy is not only a sin but also a hostile act to the state and the nation’.Footnote 106

A particular case was the work of Majdański, who addressed population issues extensively in his four books, published and republished between 1937 and 1947, combining Catholic sexual morality with highly nationalistic and racist discourse. Focusing on abortion, which he viewed as a threat to the Polish nation, he stated that, while the ‘fight of the white race for biological survival’ did not require unrestrained fertility, it did rely on the production of numerous offspring.Footnote 107 He openly praised modernity (nowoczesność) with its rationality, whenever the believers (and the nation) had enough ‘moral strength’.Footnote 108 In his post-war Poland flourishing with children, he argued that, while ‘conscious motherhood and fatherhood’ are ‘an expression of progress’, they may lead to ‘the death of the nation’.Footnote 109 Majdański's approach would become an inspiration for the post-1956 anti-abortion campaign involving the primate of Poland, Stefan Wyszyński. Both Majdański and Wyszyński, fearing that the new reproductive policies and resulting falling birth rate would jeopardize the existence of the Polish nation, used highly pro-natalist language in their criticism of the abortion law and state-supported birth control campaign.Footnote 110

Nationalism also appeared, though indirectly, in eugenics-related rationales for using the Ogino–Knaus method, present in the Catholic discourse in the 1930s. These arguments could be framed as ‘mildly eugenic’, a term we employ to underline the voluntary nature of eugenic measures commended by Catholic authors and their approval of ‘positive eugenics’ discussed below. Although a number of Catholic authors criticized hard-line eugenic ideas such as sterilization, which was condemned in Casti connubii, they still perceived Catholic fertility regulation as an opportunity to produce ‘high-quality children’ through choosing and preparing for the moment of conception.Footnote 111 The notion of ‘high-quality’ children, as it may be inferred from Zajdlicz's publication, entailed both physical and moral or spiritual excellence of the offspring envisaged as members of the ‘race’, the term used by Zajdlicz and widely present in interwar eugenic discourse. Such children, according to the Catholic author, would not ‘fill up hospitals and prisons’ because of their acts and conditions stemming from poor moral and physical health, but would guarantee a good future for the nation.Footnote 112

With their references to sterilization, ‘race’, and ‘high quality’, Polish authors participated in the global Catholic debate on eugenics that in the interwar period underwent several modifications, at times producing specific local versions.Footnote 113 Casti connubii denounced negative eugenic measures such as sterilization that would lead to the decrease of the number of children, particularly among persons deemed ‘unfit’. At the same time, the encyclical did not condemn ‘positive eugenics’, which entailed efforts to produce healthy children, particularly among ‘the fit’.Footnote 114 Catholic milieus, as stressed by Monika Loscher in her article on Austria, shared a eugenic concern about declining birth rates and about the quality of a nation plagued by alcoholism or sexually transmitted diseases, and attempted to combat them with such ‘positive eugenic’ measures as marriage counselling or education.Footnote 115

Eugenic discourse was present in the Polish birth control movement in both the pre- and post-war years, and several activists and doctors engaged in the ‘conscious motherhood’ campaign applauded eugenics, including voluntary and/or coercive sterilization.Footnote 116 Despite the popularity of eugenic ideas in the interwar years, initiatives by proponents to pass sterilization laws and other measures proved futile.Footnote 117 The presence of ‘mildly eugenic’ arguments in some Catholic advice books was thus in tune with more general cultural trends in interwar Poland and in Catholic milieus in other countries, with modernity constituting one of them, and the persistence of these ideas is visible in a number of post-war publications. In marriage preparation material published in 1952, a section on ‘Catholic eugenics’ stated that ‘children must be given a healthy body and a healthy soul’ and recommended pre-marital medical examination.Footnote 118 In this respect, Catholic discourse mirrored debates on compulsory medical check-ups before marriage, held among experts and state officials in the late 1940s.

VI

Our analysis of Catholic advice books on marriage and family published in Poland between 1930 and 1957 reveals considerable continuity in Catholic teachings on family planning, in terms of content, argumentation, authorship, and transnational influences. The Ogino–Knaus method, presented as moral, healthy, and useful for Catholics, was embedded in broader discourse on the objectives of marriage, marital sexuality, and gender roles. Owing to demographic circumstances, Catholic teachings increasingly stressed population issues, but the underlying rationale remained unchanged, despite the turbulent political and social transformations of the period in question.

Throughout the period, Poland remained transnationally connected through translations. The reception of the 1930 encyclical was a complex process, in which both the text itself and Catholic debates elsewhere influenced the ideas that Polish publications intended to transmit to the faithful. The analysis of the content shows the reception of the encyclical ideas, such as the primary and secondary aims of marriage, and the need for marriage preparation, as well as broad elaborations of the Ogino–Knaus method, developed in Catholic publications in other countries but not present in the encyclical itself. Some threads and arguments in this discourse brought Catholic understanding of sexuality closer to Protestant denominations, in spite of these being marginal in interwar Poland. However, unlike Protestants, Catholic authors rejected ‘artificial’ contraception.

As in other countries, the Catholic church in Poland actively co-constructed modernity, with its emphasis on rationality and science-based arguments, as well as ideas to reduce fertility and develop a renewed and more positive approach to sexuality. Arguments based on medical knowledge appeared across all the threads discussed in this article, from the Ogino–Knaus method to the advice to limit the number of children. Catholic authors promoted a ‘rational’ approach to fertility, even if still advocating large families and using rationality as only supportive to key moral and religious concerns. In contrast with other countries, however, the role of medical doctors in the propagation and implementation of the Ogino–Knaus method remained less prominent, to the benefit of the clergy. Polish Catholic teachings on family planning also stressed population issues, connecting Catholic management of fertility to the nation's well-being, in terms of both the numbers and the ‘quality’ of offspring.

Finally, the Polish case shows how Catholic discourse dialogued and overlapped with the secular liberal ideas of the ‘conscious motherhood’ movement in interwar Poland. In spite of mutual hostility and important differences in approach to contraception, abortion, and women's emancipation, a close comparison of Catholic and secular discourses reveals some similarities, as, for example, in their understanding of sexuality or in evaluations of particular birth control methods. The Catholic response to secularization in the realm of reproduction, which took place on the global level through the encyclical Casti connubii, also developed in the particular Polish context, and contributed to the transformation of attitudes towards fertility in Polish society. This context proved crucial in both the early 1930s and the mid-1950s, when a shift in population and reproductive policies engendered a strong reaction from the Catholic church. The interventions of the Catholic church into reproduction- and sexuality-related issues continued in ensuing decades up until contemporary times, when the church's teachings still influence legislation pertaining to LGBTQ+ rights or to reproduction in Poland, where abortion is almost completely banned and contraception is not subsidized.

Funding statement

This research is a result of the research project ‘Catholicizing reproduction, reproducing Catholicism: activist practices and intimate negotiations in Poland, 1930–present’ (principal investigator Agnieszka Kościańska), funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (Opus 17 scheme, grant number 2019/33/B/HS3/01068).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the ‘Catholicizing reproduction’ research grant team (Jędrzej Burszta, Agata Ignaciuk, Agnieszka Kosiorowska, Agnieszka Kościańska, and Natalia Pomian) for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. Many thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions, and to Joanna Baines for her editorial assistance.