There is little doubt that the populist radical right has turned into an important political force in Europe. Yet there is great variation in the electoral performances of such parties across the continent; while populist radical right parties (PRRPs) have formed part of (or provided parliamentary support for) national governments in Austria and the Netherlands, they have been absent or unsuccessful in Ireland and Luxembourg.Footnote 1 Besides these national variations, there are also important regional differences in the electoral trajectories of PRRPs. Belgium is a case in point, where such parties have historically been more successful in Flanders (the northern, Dutch-speaking part) than in Wallonia (the southern, French-speaking part).Footnote 2

The Belgian case is puzzling given that many conventional explanatory models (e.g. socioeconomic or ‘demand-side’ explanations) are insufficient to account for the asymmetrical electoral success of PRRPs. Institutional explanations (i.e. ‘external’ supply-side theories) are similarly inadequate; after all, federal electoral rules apply in both regions. This article therefore looks beyond demand- and supply-side explanations to consider the wider sociopolitical context in which parties operate.

To be sure, the traditional demand- and supply-side framework provides a useful starting point to explain the divergent electoral fortunes of PRRPs. However, it underestimates the importance of contextual factors, notably the nature of party competition and the role of the media landscape. This article combines insights derived from these different explanatory strands into a single analytical framework. The main advantage of this ‘holistic’ approach is that it generates a multifaceted picture that can supplement the two-dimensional demand- and supply-side approach.

The article employs a qualitative, comparative case study approach. In line with earlier studies (Coffé Reference Coffé2005; Hossay Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002), the findings suggest that, while demand for PRRPs seems relatively stable across Belgium, the supply of such parties has been much stronger in Flanders, where far-right groupings were able to draw on an extensive support network rooted in the Flemish independence movement. Above all, the article sheds light on contextual factors, notably the ways in which mainstream political parties and the media respond to the far right.Footnote 3 Different historical experiences have given rise to a hostile political environment for PRRPs in Wallonia, where mainstream parties and the media have created a successful cordon sanitaire. In Flanders, these actors have become gradually more accommodative towards PRRPs. Empirical support is drawn from a combination of primary and secondary sources, including semi-structured interviews with media practitioners and party leaders (N = 18; see the online appendix) as well as the existing scholarly literature on the topic.

The contribution to the field is twofold. First, the article makes an empirical contribution by shedding new light on ‘the curious case of Belgium’. Specifically, the article traces the long-term strategies that Walloon mainstream parties and the media have adopted to prevent the electoral breakthrough of PRRPs. It thereby provides insight into how the cordon sanitaire works in practice. Second, it furthers our theoretical understanding of the success and failure of PRRPs, notably by reflecting on potential lessons for mainstream parties and media practitioners elsewhere.

The argument proceeds as follows. The next section introduces the Belgian case(s). The third section highlights the limitations of conventional demand- and supply-side theories to explain the variation in the electoral performances of PRRPs. The fourth section analyses the role of mainstream parties and the media. These contextual factors help account for the presence of a very rigid cordon sanitaire in Wallonia, which has made it difficult for PRRPs to emerge. The conclusion emphasizes the role of mainstream parties and the media, and discusses the wider implications of the findings.

Background

Belgium is a federal state comprising three territorial regions (Flanders, Wallonia, Brussels) as well as three different language communities (Dutch or Flemish, French, German). The Belgian party systems and the media reflect the linguistic divisions of the country: parties generally compete in one of the language communities only, while the media is composed of a francophone system and a Dutch-speaking one (De Cleen and Van Aelst Reference De Cleen, Van Aelst, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and de Vreese2017: 99). As Kris Deschouwer (Reference Deschouwer2012: 136–137) has noted, ‘[l]ooking at election results from a national or statewide perspective is … not the usual way for Belgium. Political parties themselves and the media always present and discuss results within each language group only.’ Since the country does not have a national party system, it is possible to treat Wallonia and Flanders as two separate cases (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 179).

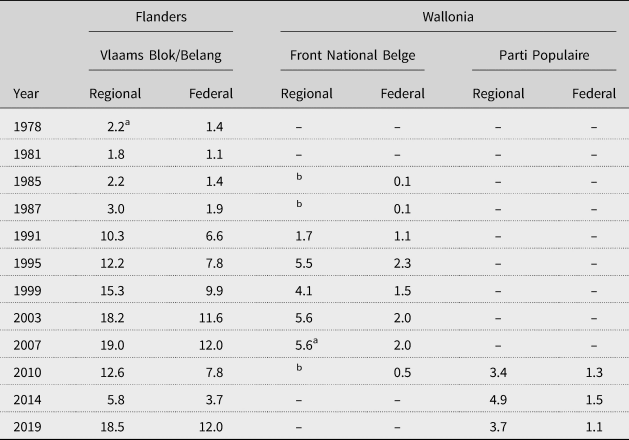

As shown in Table 1, far-right parties have historically been very successful in Flanders with the Vlaams Belang (VB, Flemish Interest, formerly known as the Vlaams Blok) but have failed to become a relevant electoral force in Wallonia (Coffé Reference Coffé2005). Flanders was home to one of the strongest and earliest manifestations of a new generation of far-right parties in post-war Europe (Art Reference Art2008). On 24 November 1991, the country made international headlines when the VB garnered over 10% of the Flemish vote. This election day, which became widely known as ‘Black Sunday’, marked the beginning of a period of electoral rise for the VB, which peaked in 2004 when the party won 24% of the vote in the Flemish parliamentary elections (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2012: 96). In the 2007 federal elections, the VB witnessed its first setback and subsequently entered a downward spiral, winning just under 6% of the Flemish vote in 2014. In the 2019 elections, however, the party experienced a remarkable resurgence when it became the second biggest party in Flanders with 18.5% of the vote.

Table 1. Percentage of Votes for PRRPs, Belgian Federal Elections, 1981–2019

Source: Belgian Interior Ministry (2019).

Notes: a = result extrapolated from existing data; b = data unavailable; – = party did not compete.

Although comparable movements have surfaced occasionally in Wallonia, with parties such as the Front National belge (FNb, Belgian National Front, 1985–2012) and, more recently, the Parti Populaire (PP, People's Party, 2009–19), the Walloon region has remained relatively ‘immune’ to PRRPs. The FNb's share of (federal) votes peaked at 2.3% in the 1995 general elections, and the party was dissolved in 2012.Footnote 4 Some issues on the FNb's agenda were taken over by the PP, a party led by Mischaël Modrikamen, who became known as a vocal supporter of Donald Trump and outspoken critic of (Muslim) immigration. Although Modrikamen is relatively well known internationally, the PP never managed to break through electorally in Wallonia. After the 2019 elections, the PP was dissolved when it lost its one and only seat in the federal parliament. In sum, ‘[r]ight-wing populism is very much a Flemish affair’ (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2012: 96).

Conventional explanations: demand and supply

To explain the rise of PRRPs, scholars typically differentiate between demand- and supply-side variables (e.g. Mudde Reference Mudde2007; van Kessel Reference van Kessel2015). The demand side emphasizes factors that help create fertile ground for PRRPs, while the supply side looks at how PRRPs are able to harness lingering demand and gain momentum. The ‘external supply side’ considers various features of the political system that affect the extent to which demand is translated into votes (Mudde Reference Mudde2007: 232).Footnote 5 The ‘internal supply side’, on the other hand, focuses on the agency (the strategies and behaviour) of PRRPs themselves (Mudde Reference Mudde2007: 256).

Demand for PRRPs in Belgium

Public opinion research suggests that there is, in fact, ample potential for PRRPs in Wallonia. First, immigration rates have historically been higher in Wallonia than in Flanders (Coffé Reference Coffé2005). When the VB broke through electorally in the early 1990s, just 4% of the Flemish population were immigrants, compared with 12% in Wallonia (Hossay Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002: 161). By January 2019, the percentage of foreigners living in Wallonia (11.4%) still exceeded the percentage of foreign residents in Flanders (10%) (Statbel 2019a).Footnote 6 In addition, the proportion of foreigners originating from countries that are particularly prone to being targeted as scapegoats by the far right (e.g. the Maghreb countries and Turkey) does not vary significantly between the two regions (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 182). Socioeconomic predictors are similarly inadequate to explain the variation in the electoral performance of PRRPs in Belgium; Flanders possesses a thriving economy with low levels of unemployment, whereas Wallonia is still recovering from industrial decline. According to the 2019 Labour Force Survey, the unemployment rate in Flanders is 3.3%, compared with 6.9% in Wallonia (Statbel 2019b).

Furthermore, Walloon voters do not have a fundamentally different outlook on socioeconomic or political topics. Using post-electoral survey data, Jaak Billiet et al. (Reference Billiet, Abts, Swyngedouw, Rihoux, Van Ingelgom and Defacqz2015) found that regional differences regarding views on immigrants are minimal, and that Walloon voters are, in fact, generally more Islamophobic than the Flemings. They concluded that the ‘stereotype of the racist Flemish and the tolerant Walloons has clearly been disproven’ (Billiet et al. Reference Billiet, Abts, Swyngedouw, Rihoux, Van Ingelgom and Defacqz2015: 100). These findings are in line with earlier studies suggesting that Flemish and Walloon voters hold similar views on sociopolitical issues (Coffé Reference Coffé2005; Deschouwer et al. Reference Deschouwer2015; Henry et al. Reference Henry, van Haute, Hooghe, Deschouwer, Delwit, Hooghe, Baudewyns and Walgrave2015).

Demand-side explanations are thus not very useful to explain the asymmetrical success of PRRPs in Belgium. In fact, many of the conventional demand-side theories would lead us to expect popular appetite for PRRPs to be stronger in Wallonia than in Flanders (Hossay Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002: 160), as the reservoir of potential far-right voters is actually larger in Wallonia (Coffé Reference Coffé2005: 81).

Supply of PRRPs in Belgium

Given that the institutional setup does not vary much across regions, external supply-side explanations are not particularly useful either in resolving the Belgian puzzle. Indeed, the same voting system applies in Flanders and Wallonia; regional as well as federal parliaments are elected based on proportional representation. The internal supply side, however, goes a long way towards explaining the variation in the electoral trajectories of PRRPs in Belgium. Specifically, the success of PRRPs in Flanders must be attributed to their organizational strength. Due to its long history, the Flemish far right was able to draw on an extensive network, which allowed it to excel at organizational tasks, mobilize voters, maintain unity and recruit qualified personnel (Art Reference Art2008; Coffé Reference Coffé2005).

The supply of PRRPs has been weaker in Wallonia. Although far-right movements emerged occasionally, they were never able to gain ground; indeed, they were often amateurish, violent and lacking any sense of direction or leadership, which frequently resulted in factionalism. The FNb is a case in point. Unlike the French Front National, for example, the FNb never managed to set up a working party apparatus. During interviews with Belgian politicians, David Art (Reference Art2011: 64) found that the FNb was described as a party of ‘poor souls’ or a ‘bunch of lunatics’ – even by former FNb members. In the words of Patrick Hossay (Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002: 170), ‘If the Flemish radical right was consolidated in a nationalist political home, the radical right in Wallonia was fragmented for lack of one.’

In sum, while demand for PRRPs seems relatively constant across Belgium, the supply of such parties is much weaker in the francophone south. However, although the organizational argument can account for some of the success of the VB (notably the party's electoral persistence), it fails really to explain why far-right parties emerged in Flanders and never managed to break through in Wallonia. First, it fails to explain the timing of their electoral breakthrough; after all, the VB had strong organizational capacity long before its initial electoral breakthrough (Art Reference Art2008: 422). Second, there are examples of PRRPs that were highly successful despite poor organizational capacity; the List Pim Fortuyn (LPF) in the Netherlands is a case in point (de Lange and Art Reference de Lange and Art2011). Third, the PP was arguably more professional and better organized than the FNb; yet, it failed to break through electorally. Thus, demand- and supply-side explanations cannot fully account for the asymmetrical electoral performances of PRRPs in Belgium. We therefore need to consider the broader context in which these parties compete.

Beyond demand and supply: contextual factors

The electoral performance of PRRPs is generally equated to a marketplace, in which their success or failure is contingent on voter demand and party supply. This conventional explanatory model fails to consider the complexities of the electoral marketplace, as it under-theorizes the role of the media landscape as well as the nature of party competition. Contextual factors go beyond demand- and supply-side variables in that they determine the openness or accessibility of the electoral market. The underlying assumption is that political parties do not exist in a vacuum. In order to explain the divergent success of PRRPs, we need to take into account the context in which they operate. Their success ultimately hinges on the way in which they are received and perceived in a given polity. If the environment in which they operate is hostile, their success becomes less likely; if they enter a public sphere that is receptive, they are more likely to succeed (see Art Reference Art2007).

Mainstream parties and the media interact with demand- and supply-side variables without really fitting into either of these two categories. Specifically, they can act as ‘buffers’ by damping demand for PRRPs, or they can act as ‘catalysts’. For instance, they can contribute to generating demand by politicizing issues (e.g. immigration). They can also facilitate the supply of PRRPs. As such, the media can choose to offer a platform to PRRPs to spread their views, whereas mainstream parties can create or occupy space in the electoral market. Therefore, it makes sense to remove mainstream parties and the media from the conventional framework by instead conceptualizing them separately as ‘contextual factors’. In other words, this article suggests that mainstream parties and the media straddle classical demand- and supply-side explanations since they interact with both voter demand and party supply (see also Ellinas Reference Ellinas and Rydgren2018). Studying contextual factors can help us understand why PRRPs succeed ‘in making their voices heard in the public sphere in the first place’ (Koopmans and Muis Reference Koopmans and Muis2009: 643). As shown below, the behaviour of mainstream parties and the media is crucial in obstructing or encouraging the electoral breakthrough of PRRPs.

The party system

The existing literature on the success and failure of populist parties tends to ascribe a relatively passive role to mainstream parties (Meguid Reference Meguid2005: 347). Indeed, mainstream parties are generally seen as ‘victims’ who are suffering the consequences of the success of PRRPs. This article treats mainstream parties as agents that play an active role in altering traditional political cleavage structures and bringing about related shifts in voting patterns (Bale Reference Bale2003). Rather than being static entities, mainstream parties interact with changes in the political environment. As such, they control the gateway to the electoral arena (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). Their behaviour can pre-empt the rise of PRRPs or, indeed, facilitate it (Bornschier Reference Bornschier and Rydgren2018: 212).

The nature of party competition in Flanders is different from Wallonia, thereby making it more accessible to the rise of PRRPs. Specifically, the Flemish party landscape is more fragmented than the francophone one (De Winter et al. Reference De Winter, Swyngedouw and Dumont2006: 934). To understand this difference, we need to consider the regional dimension. Indeed, regionalism has had a profound impact on Belgian parties. In the past, the party system was organized around three social cleavages: economic, denominational and communitarian (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2012). These cleavages were solidified into ‘pillars’ (or subcultures) that structured nearly every aspect of life. Every pillar produced its own political party, and members of a particular pillar would generally vote for their own ‘pillar party’: liberals, Christian democrats and social democrats. On top of these traditional cleavages, Belgium also has a cross-cutting linguistic cleavage. The linguistic cleavage became increasingly salient over the course of the 20th century and ultimately transformed Belgium into a federal state, whereby the country was divided into two distinct party systems, each of which developed a different pattern of party competition.

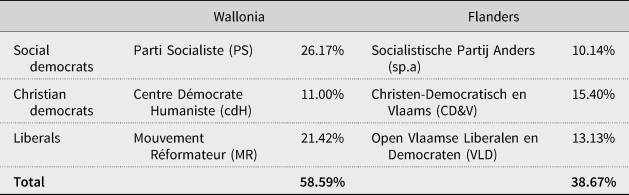

The erosion of the Belgian social pillars has contributed to the fragmentation of the Belgian party systems. However, depillarization has been less pronounced in Wallonia than in Flanders (van den Berg and Coffé Reference Van den Berg and Coffé2012). Political fragmentation generally implies increased electoral volatility as well as partisan dealignment or detachment from traditional parties (e.g. Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, McAllister, Wattenberg, Dalton and Wattenberg2002), which, in turn, increases the ‘availability’ of voters. This trend is more pronounced in Flanders, where support for mainstream parties has plummeted. In the 2019 Belgian federal election, traditional party families won less than 40% in Flanders, whereas nationalist parties (the New Flemish Alliance or N-VA and VB) won the lion's share of the vote (43.33%), compared with 60% in Wallonia (see Table 2).

Table 2. Votes for Mainstream Parties in Belgian Federal Elections, 2019

Source: Belgian Interior Ministry (2019).

Note: Electoral results are given per region.

The strength of Walloon mainstream parties (notably the Parti Socialiste or PS) can be attributed to the fact that traditional societal cleavages are still more pronounced in the francophone south of Belgium. Political parties typically reflect cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Western European politics have been defined by two different cleavage dimensions: an older, economic conflict that revolves around the degree of state involvement in the economy, and a newer post-materialist, sociocultural rift that concerns novel issues, notably immigration. In Western Europe, this new dimension has become increasingly salient in recent decades. It is best conceptualized as ranging from green/alternative/libertarian (GAL) views promoting cultural pluralism on the left, to traditional/authoritarian/nationalist (TAN) positions advocating cultural homogeneity and protectionism on the right (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002).

The salience of traditional cleavage structures can dampen demand for PRRPs; if old cleavages remain prominent, it is more difficult to mobilize voters on new issues (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). In other words, old cleavage structures can act as a protective ‘shield against the framing attempts of rising collective actors’ (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1995: 4). Jens Rydgren and Sara van der Meiden (Reference Rydgren and van der Meiden2019) have shown that one of the reasons that Sweden witnessed the rise of a PRRP (thereby ending the country's perceived ‘immunity’ to such tendencies) was a shift in cleavage structures; as new sociocultural cleavages gained prominence, the social democrats lost their hegemonic position, thereby opening up space for radical right-wing mobilization. Scholars have shown that social cleavages carry different weights in the two Belgian party systems (De Winter et al. Reference De Winter, Swyngedouw and Dumont2006: 938). In Wallonia, the traditional, economic left–right dimension is still the most relevant for determining electoral behaviour. In Flanders, on the other hand, a new (TAN) dimension has become dominant, as ethnocentrism and political alienation have become the main factors (De Winter et al. Reference De Winter, Swyngedouw and Dumont2006: 953).

There are two ways to explain the variation in the salience of cleavage structures: ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ approaches (Rennwald and Evans Reference Rennwald and Evans2014). From a ‘bottom-up’ perspective, the importance of the economic cleavage in Wallonia may simply be understood as a reflection of the socioeconomic situation. Wallonia is poorer than Flanders; although it was one of Europe's first industrialized regions, Wallonia has faced economic decline since the end of the Second World War. In Flanders, post-war industrialization was led by small and medium-sized enterprises and multinationals and, as a result, by the 1960s, Flanders was prospering, while the Walloon economy was shrinking (De Winter et al. Reference De Winter, Swyngedouw and Dumont2006: 183). Socioeconomic issues may therefore simply be more relevant to Walloon voters.

However, as Hilde Coffé (Reference Coffé2005: 128) has argued, the strength of the economic cleavage in Wallonia cannot be explained solely by the different economic situation. Instead, it must also be attributed to the behaviour of mainstream parties. From a ‘top-down’ perspective, it can be argued that Flemish social democrats contributed to decreasing the salience of the economic cleavage. In line with other social democratic parties of the Third Way, the Flemish social democrats revised their welfare agenda in the early 1990s by departing from an outspoken leftist position and instead moving closer to the centre right (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 190). As a result, socioeconomic issues became depoliticized: ‘This Third Way direction also implied that economic and welfare policies became a more consensual area, with limited party disagreement. … As such, it receives less attention in political debates, thereby leaving more space for other political issues’ (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 190).Footnote 7 Seen from this point of view, it is not surprising that the rise of the VB went hand in hand with the decline of the Flemish centre left. When the VB had its initial electoral breakthrough in the early 1990s, nearly one-fifth (19%) of the voters came from the social democratic Socialistische Partij (SP), while over 14% of the socialist trade union shifted their vote over to the VB, thereby turning the VB into ‘the biggest labour party’ in Flanders (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 183).

In Wallonia, by contrast, the PS successfully managed to ‘freeze’ traditional lines of conflict. It has done so by maintaining a traditional leftist agenda and discourse. Unlike most other social democratic parties in Europe, the PS has maintained a central position in the Walloon party landscape. Despite moderate electoral losses, the party continues to play a pivotal role in the socialist ‘pillar’. As such, the links between the PS and its socialist subculture remain very close. Thanks to these links, the party managed to hold on to its core electorate. It has done so through a combination of localized politics (‘socialism of proximity’) and clientelist practices – for instance, by reserving jobs for party members in state enterprises, or by making use of the party's auxiliary (or ‘pillar’) organizations, which grant the party direct access to public services, allowing it to distribute material benefits to its members (Coffé Reference Coffé2008: 184).

Based on interviews with PS politicians, Coffé (Reference Coffé2005) found that party representatives considered their proximity to voters one of their main strengths. According to the then-leader of the PS, Elio Di Rupo, ‘customer loyalty’ with voters is one of the party's biggest strengths; moreover, ‘PS candidates do not mind putting in a good word for their voters with city administrations, or helping their constituents figure out how gas and electricity connections work’ (Coffé Reference Coffé2005: 146–147). By doing so, the PS managed to strangle demand for PRRPs. In other words, lingering demand has been absorbed by the PS. In that respect, the PS has acted as a buffer to dampen demand for the far right (Coffé Reference Coffé2008).

Besides absorbing demand for PRRPs, the PS has also absorbed the supply of PRRPs. The party has a history of recruiting politicians with nationalist (and sometimes even racist) tendencies, and successfully neutralizing them by embedding them into the wider socialist party structure. The case of José Happart serves as a useful example to illustrate this point (Coffé Reference Coffé2005: 153; see also Demelenne Reference Demelenne1995). Happart was born in Herstal, a suburb of Liège. When his father was expropriated in the 1960s due to the expansion of the steel industry, the latter proceeded to buy a new farm in Sint-Pieters-Voeren, a town which formed part of the francophone province of Liège. In 1962, the municipality of Voeren became part of the Dutch-speaking province of Limburg. Happart campaigned on behalf of the francophone population for the region to be returned to Liège. In 1982, the linguistic struggle intensified when a local party called Retour à Liège (Return to Liège) won a majority in the municipal elections and nominated Happart as its mayoral candidate. Happart refused to speak Dutch, and to many francophone Belgians he became a symbol of anti-Flemish resistance. Initially, Happart was only active in local politics and did not seek to connect to established political parties. At the 1984 European elections, however, he was offered a place as an independent candidate on the list of the PS and was elected with nearly 235,000 personal votes (Volkskrant 1996). That same year, Happart joined the PS. In the words of Coffé (Reference Coffé2005: 154), ‘[b]y receiving [Happart] with open arms, the PS swallowed almost the entire Walloon Movement. … He was, to some extent, an outsider of the political system and was therefore able to appeal to discontent voters. In that way he formed a barrier against the extreme right.’

The Happart case was not an isolated incident. There are several other examples of local PS politicians flirting with nationalist and/or xenophobic ideas (see RTBF 2015). Incidentally, the PS has not always managed to ‘discipline’ local PS politicians, which has occasionally resulted in expulsions (Le Soir 2015). However, the official party line of the PS has remained unequivocally in favour of multiculturalism and immigration. This can be explained by the different experiences the two regions have had with immigration. The francophone region has a long history of immigration. In the wake of the Second World War, the Belgian government recruited Italian workers for the country's booming industries, most of whom settled in Wallonia (Coffé Reference Coffé2004: 198). From their arrival, foreign workers were incorporated into existing social structures, notably trade unions, which pre-empted the emergence of Italian political associations because it effectively depoliticized and neutralized any potential immigrant community leaders (Hossay Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002: 171). This practice, which fostered a relatively seamless integration, set the tone for future waves of immigrants.

In Flanders, on the contrary, immigrant labour is a relatively recent occurrence; it was not until the 1960s that the Belgian government started to recruit Moroccan and Turkish guest workers to supplement the declining supply of migrants from southern Europe. Unlike Italian workers, the guest workers settled in cultural enclaves and remained relatively isolated. While antagonism towards immigrants started rising in Flanders, francophone politicians strategically advocated voting rights for migrants in an attempt to increase their voter bases (Hossay Reference Hossay, Schain, Zolberg and Hossay2002: 173). These different experiences help explain why migration became more politicized in Flanders than in Wallonia. Walloon mainstream parties (notably the PS) have played an important role in defusing the debate around immigration. By maintaining the salience of the economic line of conflict, they effectively ‘froze’ existing cleavage structures, which hampered the introduction and politicization of a new, cultural axis.Footnote 8 In Flanders, mainstream parties contributed to the introduction of a new political cleavage by co-opting the nationalist agenda of the VB.

To be sure, in both regions, mainstream parties have agreed not to cooperate with the far right by means of a political cordon sanitaire.Footnote 9 However, the cordon could not prevent the breakthrough of the VB in Flanders. First, it was set up after the VB had made important electoral gains at the local level. Second, it became porous quickly; barely 40 days after signing the agreement, the then-chairman of the Flemish nationalist People's Union (VU) Jaak Gabriëls proclaimed in an interview with a local newspaper that the cordon was absurd, and that it would ultimately grant too much publicity to the VB (Coffé Reference Coffé2005: 165). Partly due to the defection by the VU, the cordon became less effective; after all, if a cordon is not fully ‘airtight’, it is less likely to fulfil its purpose (Art Reference Art2011: 44).

The media landscape

The Flemish media also contributed to the ‘making of the issues’ of the VB (Walgrave and De Swert Reference Walgrave and De Swert2004). Just like mainstream parties, the media can play a crucial role in generating favourable or unfavourable opportunity structures for PRRPs to thrive. The ways in which the media approach the far right is shaped by journalistic norms (Ellinas Reference Ellinas2010: 211).Footnote 10 Flemish media practitioners have gradually become more accommodative towards PRRPs than their francophone colleagues, who adhere to strict demarcation (de Jonge Reference de Jonge2019).

In Belgium, parties are represented on the board of their public service broadcasters (the Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroeporganisatie (VRT, Flemish Radio and Television Broadcasting Organization) in Flanders and the Radio-Télévision belge de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (RTBF, Belgian Radio and Television of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation) in Wallonia) in proportion to the number of votes they have won in their respective language communities.Footnote 11 After the VB's initial electoral breakthrough in 1991, the party won seats on the board of the VRT. In response, the RTBF came up with a loose set of guidelines to ensure that this would never happen in Wallonia. These guidelines stipulated that extremist actors would be barred from participating in debates and never be featured in livestream.Footnote 12 The aim was to obstruct extremist parties from gaining influence. Specifically, the RTBF feared that the decision to grant access could not easily be reversed.

Based on these guiding principles, the RTBF chose to deny access to the FNb in the run-up to the 1994 elections because they considered the party to be racist and xenophobic, thereby clashing with RTBF principles. This led to a series of lawsuits against the francophone media, most of which were won by the FNb since the RTBF did not have sufficient evidence to show that the party was, indeed, racist and xenophobic.Footnote 13 In response, the RTBF set up a detailed vetting process to comb through the publications of parties they suspected of extremism. The aim was to demonstrate that some of their points ran contrary to certain legal principles – notably those enshrined in the non-discrimination clause of the European Convocation of Human Rights. In 1999, the Council of State ruled that the RTBF had the right to deny access to parties they considered undemocratic. The court ruling was based on the 1973 law on the Cultural Pact, which regulates media access for political groupings (Jamin Reference Jamin2005: 98).Footnote 14

Since there was a consensus among francophone practitioners, the cordon sanitaire médiatique was formalized by the Superior Council of the Audio-Visual (CSA) and eventually became legally binding for electoral campaigns (CSA 2011). The cordon stipulates that during election campaigns, francophone audio-visual media cannot provide ‘live’ access to people who are linked to parties that are liberticides, which roughly translates into ‘profoundly hostile to freedom’ (CSA 2012). Although the regulation only applies to electoral campaigns, most editors-in-chief voluntarily adhere to this principle year-round.Footnote 15

To date, the RTBF continues to scrutinize party publications in detail in the run-up to elections to determine whether a party abides by the rules of democracy.Footnote 16 This process is taken very seriously. As the director of legal affairs explained, ‘I assume my responsibilities. I examine these party programmes before every election. It takes a lot of time, but that's the only way to fight non-democratic parties – that is to say: show where and how they do not respect the rules of democracy.’Footnote 17 There was a remarkable sense of solidarity among francophone media practitioners, including those working for private and print media outlets. Most interviewees expressed a sense of pride in the policy; maintaining the cordon médiatique was considered a matter of principle.

The written press also adheres to this ostracizing principle. The election of Donald Trump in the US only reassured francophone media practitioners. In a televised debate about the future of the cordon sanitaire organized by Radio Television Luxembourg (RTL) in the aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election, the editor-in-chief of Le Soir explained, ‘It's a matter of values. We will not change our rules now that Trump has been elected. The experience that the francophone media has had with the cordon médiatique seems to have borne fruit to this date’ (Le Soir 2016). Thus, Walloon media practitioners have set up barriers making it difficult for PRRPs to access mainstream media platforms.

This was not the case in Flanders, where the cordon sanitaire médiatique was never formalized. Although Flemish media outlets did not initially treat the VB as an ‘ordinary party’, media coverage became less hostile over time (Schafraad et al. Reference Schafraad, d'Haenens, Scheepers and Wester2012). In the early 2000s, there was still a broad consensus among Flemish news editors to combat the VB. For example, in May 2003 (one day before the federal elections), an article appeared in De Standaard in which then editor-in-chief Peter Vandermeersch listed five reasons to vote for or against each of the major Flemish parties, but then explicitly stated that there was no valid reason to vote for the VB (De Standaard 2003).

The Flemish public broadcaster also took a clear stance against the VB. In a special note on its democratic and societal role (entitled ‘De VRT en de democratische samenleving’), the VRT explained that it would be particularly cautious when reporting on the VB because it was ‘not a political party like any other’ (see De Standaard 2001). However, as one interviewee pointed out, this directive has since ‘disappeared somewhere in a drawer’.Footnote 18

This can partly be explained by the rapid growth of the VB. According to several interviewees, the demarcation strategy simply became unsustainable. When asked why there was no Flemish equivalent of the cordon médiatique, one journalist explained there had been one, but that it eroded after 2004 when the VB was sentenced for racism.Footnote 19 The subsequent name change from Vlaams Blok to Vlaams Belang caused some of the quality newspapers to change their editorial line towards the VB. Many interviewees referred to an editorial published in 2004 by Peter Vandermeersch in De Standaard, where he argued that the name change signified a return to a normal political landscape in which the cordon sanitaire would be redundant (De Standaard 2004a). In the same year, De Standaard (2004b) published an op-ed by one of the leading members of the VB, Filip Dewinter, thereby granting direct access to the party for the very first time.

This decision marked a critical turning point, as it provided an incentive for other newspapers to follow suit.Footnote 20 In June 2016, the left-leaning De Morgen (2016a) published an extensive featured interview with VB figurehead Filip Dewinter. In a corresponding editorial, editor-in-chief Bart Eeckhout explained the reasoning behind this decision: ‘This “independent newspaper” has a social conviction. … Journalistic interest, especially for disturbing, deviating and conflicting opinions, is an integral part of that conviction’ (De Morgen 2016b). When interviewed, Eeckhout elaborated on this justification by explaining that, as a journalist, he had learned to become relatively self-critical and cautious about judging people who vote for PRRPs by distancing himself from this classically progressive way of thinking. Instead, he was interested in analysing what motivates people to vote for these parties: ‘You cannot look at this with an open mind while also maintaining that those politicians are not allowed to speak. That simply no longer works from a journalistic point of view.’Footnote 21

In general, media practitioners in Flanders seemed to abide by different journalistic standards from their Walloon colleagues. In Wallonia, journalists have consistently narrowed the opportunities available to PRRPs, while the Flemish media did not have any rigid and formal guidelines prior to the rise of the VB. Due to this flexible stance, Flemish media practitioners became gradually more receptive to PRRPs.

Conclusion

As Art (Reference Art2008: 437) has noted, ‘by ignoring historical legacies, or treating them as a residual variable, one misses the underlying causes of the radical right's success and failure’. Different historical experiences have given rise to a very hostile environment for PRRPs in Wallonia, where mainstream parties and the media have created an effective cordon sanitaire against the far right. In Flanders, on the other hand, mainstream parties and the media have generated a relatively ‘open’ electoral market by providing a hospitable environment for PRRPs to thrive.

Previous research has shown that the far right can have a ‘contagion effect’ on mainstream parties; specifically, PRRPs can pressure established centre-right and centre-left parties to shift their policy agendas rightwards, notably by advocating stricter rules for immigration (van Spanje Reference van Spanje2010). Contagion may even occur in countries where PRRPs do not pose a direct electoral threat, as illustrated by the UK Labour government in the late 1990s, when politicians toughened their stance on immigration in response to voter and media concerns (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010: 411). However, as Rydgren has noted (Reference Rydgren2005: 429), ‘right-wing populism is not contagious (in the sense that epidemics are); it only diffuses if actors want it to diffuse’ (emphasis in original). If there are no actors (i.e. parties) or channels (i.e. the media) to diffuse right-wing populist agenda items, they are less likely to spread and become normalized.Footnote 22

Although Wallonia is certainly not immune to the far right, it is unlikely to witness the rise of a PRRP – as long as media practitioners and mainstream politicians continue to uphold their strict non-engagement policy. The findings indicate that the electoral performance of PRRPs depends on the degree of political and social ostracism they receive in a given polity. More generally, the article suggests that PRRPs are less likely to break through electorally when mainstream parties and the media consistently restrict their opportunity structures. The timing and rigidity of the demarcation strategy seem to play a key role in its effectiveness (see Heinze Reference Heinze2018); because mainstream parties and the media have created a fully ‘airtight’ cordon, they have narrowed the opportunities for PRRPs to break through. In other words, in Wallonia, PRRPs are ‘nipped in the bud’ (i.e. checked before they become big enough to matter).

Given that many other European countries have already witnessed the breakthrough of a successful PRRP, it is questionable whether the Walloon model could be exported beyond the Belgian borders. Nevertheless, lessons from Belgium could shed new light on the breakthrough of PRRPs elsewhere. The findings indicate that the reactions of mainstream parties and the media play a crucial role in the success and failure of PRRPs. More generally, the article shows that enriching conventional demand- and supply-side theories with contextual explanations can help generate new insights. Finally, while this study has enhanced our understanding of the electoral trajectories of PRRPs in Belgium, it has not assessed how these different trajectories have affected the overall state of democracy in the country. This is an interesting (albeit complex and normative) question that merits further attention.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please go to https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.8

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers for their fair and thoughtful comments.