A. Introduction

In the Federal Republic of Germany, sexual delinquency among adults originally was subject to punishment in two variants. Both offenses were linked to compulsive acts, either violence or serious threat. However, they differed in the type of forced sexual contact—sexual intercourse in the case of rape vs. sexual acts in the case of sexual assault. But the sanctions provided for these offenses have continuously been made more severe since the late 1990s. In addition, the criminalized scope was expanded to some extent, namely by including intramarital relations. Furthermore, punishable constellations were not only supplemented by other impairments such as acts of humiliation, but also by methods of committing the offense, particularly utilizing the fear of being at someone’s mercy.Footnote 1 Apart from this however, the prerequisite for a criminal penalty essentially remained sexual interaction, which was initiated in response to at least some extent of actual or expected physical resistance of one of the persons involved.Footnote 2

This changed in 2016 when German law relating to sexual offenses was based on an “agreement standard” by a fundamental and far-reaching revision. Since then, any sexual activity that takes place despite noticeable dissent is punishable.Footnote 3 As a result, any sexual contact that is initiated despite the fact that the other party evidently shows non-consent—at least from the perspective of an institutional ex-post consideration—can be sanctioned in the same way as in a case of coercion.Footnote 4 It is likewise such a so-called sexual transgression if the people involved cannot express or indicate opposition, for example, because they are drugged or being threatened or because the events occur so suddenly. In addition, Article 177 of the German Penal Code (StGB) stipulates higher penalties for numerous constellations (for example if physical coercion is used, if sexual intercourse is forced, if perpetrators act jointly, or if physical injury is inflicted). Apart from some atypical special cases, the law provides for imprisonment between six months and fifteen years, depending on the facts of the case.

Similar transitions to the “no means no” model were made in the legal systems of other countries as well.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, for Germany, this is an act of adaptation worth investigating. The revision of Article 177 StGB is not simply a part of a comprehensive and never-ending process, which has already resulted in vast extensions of criminal liability in the “sexual field”—for example in the sexual abuse of children and young adults, child pornography, and so-called grooming.Footnote 6 The revision of Article 177 StGB also incorporates a marked change of the structure of the law relating to sexual offenses which expresses a gender-political commitment as well as a characteristic stance of criminal policy, which pursues the aspiration of “progressive” criminalization. Based on the example of the law on sexual offences, the following Article discusses this attitude which is typically developed by social movements in view of solving many different socio-political problems. In particular, the stance is put up for debate (Section E.) after reconstructing the part it played in enforcing the “no means no” model described in Section B. and considering the consequences that can, so far, be determined for these new criminal provisions shown in Section C. The aim of the text is, therefore, to observe processes of criminalization and its consequences from a criminal-sociological perspective, without developing a position on the criminal norms in question.

B. Legislative Acknowledgment of the “No Means No” Model

I. Criminal-Sociological Foundations

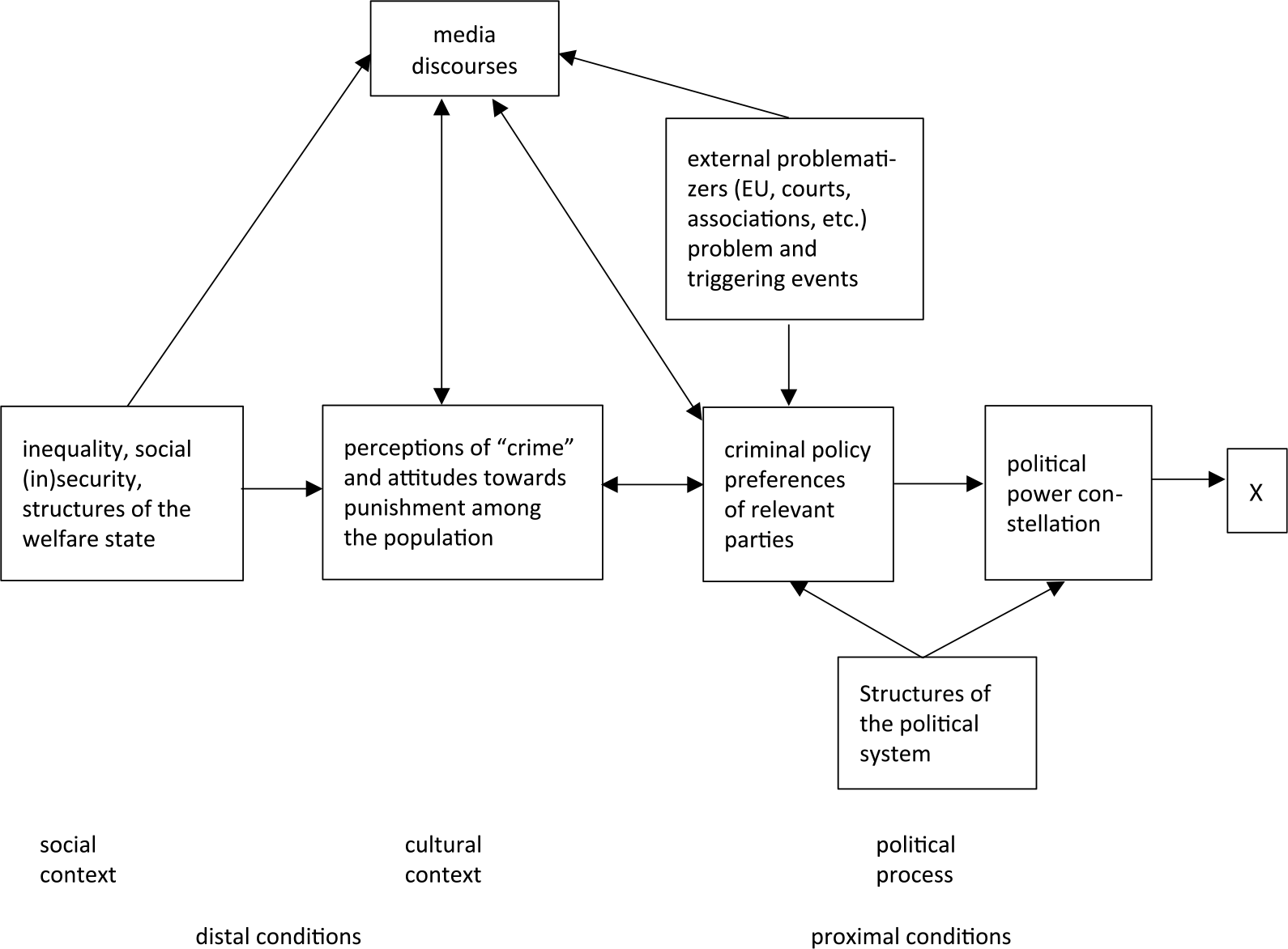

A number of conditions have proved informative for a criminological and political science analysis of legislative processes. Figure 1 summarizes these factors.Footnote 7 If the research focus “X” is on long-term development trends in a country, such as punitive or non-punitive trends there, the primary drivers are distal factors and the structures of the political system. If the focus “X” is on shorter-term processes, such as the term a party is ruling, or on reconstructing individual acts of legislation, proximal factors move into the foreground. Typically, the power position and criminal policy orientation of the actors involved prove critical, sometimes also the anticipated intervention by veto players or the input from entities outside of politics. Footnote 8 This was also the case in the 2016 revision of Article 177 StGB. The specific process of this legislation is an example of the extraordinary influence an external initiation may occasionally exert. Its dynamics strengthened the situational power position of one group of actors to such an extent that leeway in political decision-making was almost abolished and the significance of partisan controversies substantially neutralized.

Figure 1. Conditions of criminal legislation.

II. Specifics of the Legislative Procedure

A first external trigger was caused in May 2011 by the so-called Istanbul Convention, which led to certain minimum requirements to be met by national law relating to sexual offenses.Footnote 9 As a result, the German ruling parties were willing to review the need for a limited revision. To this end, a panel of experts was convened in the spring of 2015. In addition, some requirements of the Istanbul Convention were to be met by smaller fast-track changes of the German penal code. The Ministry of Justice, led by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), presented a draft containing some minor adjustments in July 2015.Footnote 10

A second outside initiation came from several women’s associations which took up the impetus of the Istanbul Convention and built a professional campaign. Since mid-2014, they had submitted a draft bill of their own and a number of mutually coordinated policy papers and expertise in addition to a large-scale collection of signatures. These initiatives all extended beyond the case-oriented closure of protection gaps and aimed at demanding a “no means no” provision. Using this slogan, these initiatives were systematically placed in the media, and they were, furthermore, picked up by the oppositional parliamentary groups of the Green and the Left parties, whose own legislative initiatives were based on it.Footnote 11 But the whole pressure would “hardly have been sufficient” to be successful.Footnote 12 Even the original draft by the Ministry of Justice, although lagging behind the demands of the women’s associations, was initially perceived as going too far by some ministries led by the Christian Democratic and Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and blocked in the cabinet until December 22, 2015.

The third and decisive impetus came from reports about numerous sexual harassments at the Cologne Cathedral Square on New Year’s Eve of 2015 and 2016. This event was discussed extensively and intensely over months in all the media, although its details and contexts of interaction could only be reconstructed to a limited extent up to this day.Footnote 13 This resulted in mixing up large parts of the debate on the problems of the migration processes that were going on at the time with considerations of sexual threats and a diffuse need for change to the penal law installed to counteract such acts.Footnote 14 The constant and sometimes highly emotional discussionsFootnote 15 increased the support for the criminalization of all undesired sexual contact, not only among the population but gradually also among politicians who had so far been reluctant. Quite a few women’s associations that had realized a good opportunity joined an alliance exclusively aimed at changing Article 177 StGB. This alliance launched intense actions to influence parliamentary groups: A postcard action and a petition, demonstrations, conferences, and a letter of demands publicly handed over and signed by numerous “celebrity experts”Footnote 16 and various organizations.

While the federal government then introduced the original draft by the ministry to the German parliament (Bundestag) in April 2016, almost all the comments across parliamentary groups at the first reading favored a more comprehensive revision. Then “some women from the governing parliamentary groups seized the historic chance,”Footnote 17 that, in view of the public debates, even some of the right-wing politicians who “as yet had reservations with respect to such a far-reaching correction of the law relating to sexual offenses no longer dared to put up resistance.”Footnote 18 They authored a so-called key issues paper which was presented to the legal committee of the parliament on June 1, 2016 and adopted there as a modified draft.Footnote 19 Despite the enormous extent of the change—the“no means no” model, the restructuring of Article 177 StGB, and the partial increase of penaltiesFootnote 20—the bill was adopted by the Bundestag before the summer break on July 7, 2016. A regular judicial review of the new Article 177 StGB was not possible in such a short time, which is why the Research Service of the Bundestag was only asked after the parliamentary resolutions to study the implications of the revision for the legal system as a precaution.Footnote 21 Furthermore, in a great rush, that is, three days before the bill was adopted, the ruling parliamentary groups linked it to an extension of powers under the law on foreigners for the deportation of migrants who had committed an offense.

III. The Role and Criminal Policy Logic of Social Movements

In an actor-oriented approach, the emergence of the new Article 177 StGB was significantly shaped by interest groups, who could utilize a trigger event like New Year’s Eve in Cologne to assert their criminal policy concerns. For this reason, the respective women’s associations considered the revision as an enormous success of their strategy of legal and political mobilization.Footnote 22 While such processes are by no means typical of the development of criminal law, they are also not an exception. In criminal sociology, such initiations of criminal legislation by the civil society had long been described with a view to other social movements. These typically are collective actors who tend to present their own moral system as generally binding for all and to mobilize the government and criminal law against social conditions that are not compatible with it. This was initially analyzed based on clerical and/or other conservatively or etatist-oriented communities, Footnote 23 but in the meantime, it is not these “typical,” but rather “atypical moral entrepreneurs” who dominate.Footnote 24 These are groups who advocate, for example, protection of children and victims, preserving the environment, or fairness in the economy, politics, and sports and who try to employ the state and, in particular, its criminal law for their goals, even if they pursue liberal and emancipatory issues like human rights issues. Footnote 25

In the assertion of the German “no means no” model, such interest groups were remarkably closely interlinked with academic actors. In general, the influence of legal and social science studies on criminal law is estimated to be small.Footnote 26 But this was different in the case of the new Article 177 StGB. In the media debate mentioned above, the low rate of penalties for sexual offenses often provided a scandalized aspect. Footnote 27 Reference was often made to a study by the Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony (KFN), a significant German research facility. The paper that was published in 2014 showed a declining penalty rate with local differences and explained it not just with a locally different decline in persecution intensity by the police, but implicitly also with the criminal laws at the time.Footnote 28 Consequently, the KFN itself pleaded for a punitive reform of Art 177 StGB. Some criminal law scientists were even more involved in the campaign of the women’s associations. Well-known voices advocated an extension of the law relating to sexual offenses, both in scientific and in the general media;Footnote 29 they wrote respective expert opinions for the women’s associations, supported their objectives as experts in the legislative procedure, and acted as central trusted sources in the parliamentary space.Footnote 30

Irrespective of these acts of cooperation, the objective of the interest groups discussed here was the same as has been demonstrated for other atypical moral entrepreneurs: For them, criminal law is a means to an end. They use it as an instrument of “social engineering” and to achieve socio-political changes they envisage. The idea of “progressive” criminalization that is becoming effective herein includes the thought that certain forms and directions of using criminal law are not only legitimate but also functional for achieving the objectives of the respective group. These assumptions are mostly viewed as matters of course, such that they remain implicit and are not explained in detail by the respective actors. But with regard to the “no means no” provision, the detailed issues to be solved by new penal law, in this case the extension of Article 177 StGB, were occasionally stated: Characteristic was the joint assumption that violations of sexual boundaries were punished much too rarely until 2016. This was attributed to a low frequency of reports to the police and a high rate of terminated proceedings and acquittals. A main reason for this offense-typical selectivity of law enforcement was seen in the structure of criminal law, for example the fact that some variants of behavior simply were not punishable Footnote 31 notwithstanding an allegedly common public demand for punishment. Footnote 32 As a result, compared to what was considered to be the “genuine” rate of offenses, there had not been enough investigations, prosecutions, and convictions before 2016. Footnote 33 The revision of Article 177 StGB was primarily meant to be able to punish considerably more often. Footnote 34 The number of cases registered by the police was expected to grow Footnote 35 —on the one hand, because reporting an offense was going to be promising in constellations that had not been punishable before (“criminalization effect”), on the other hand, because the revision was to encourage people to also report cases that were previously already punishable (“activation effect”). In addition, the extension of criminalized behavior was expected to reduce occasions for terminations of proceedings by prosecutors or acquittals by a court and increase the rate of convictions (“enforcement effect”). Footnote 36

C. Consequences of the “No Means No” Provision in Criminal Law Practice

I. Changes in the Frequency of Criminal Prosecution?

The fact that the revised Article 177 StGB was decisively expected to change the practice of criminal law is cause to look into consequences of the “no means no” provision. With regard to reports to the police and convictions, it is, by now, possible to determine whether the criminal statistics show an increase since 2017. However, it would be incorrect for a number of reasonsFootnote 37 to look at the data of cases involving only Article 177 StGB. Because the revision has the effect that case types are assigned to it which initially were prosecuted based on another provision, such shifts in offenses would easily be misinterpreted as an effect of the revision. To avoid this, the data must be analyzed for the entire group of offenses—Articles 177-179, 174 StGB—as a function of time. It can be seen on this basis that the desired rise in the number of criminal charges has not occurred as yet. According to the official statistics, the number of cases registered by the police for this group of offenses has only moderately increased from 2017. While there was a 3% to 4% increase compared to the immediately preceding years, the significantly higher level from the first decade after 2000 was not reached by far—see Table 1.

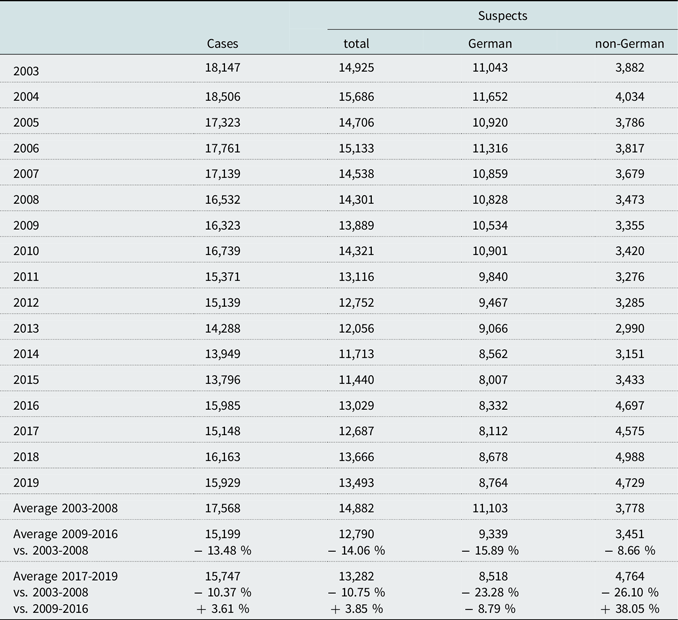

Table 1. Development of registered sexual offenses, Articles 177-179, 174 et seq. StGB: Cases and suspects recorded by the policeFootnote 38

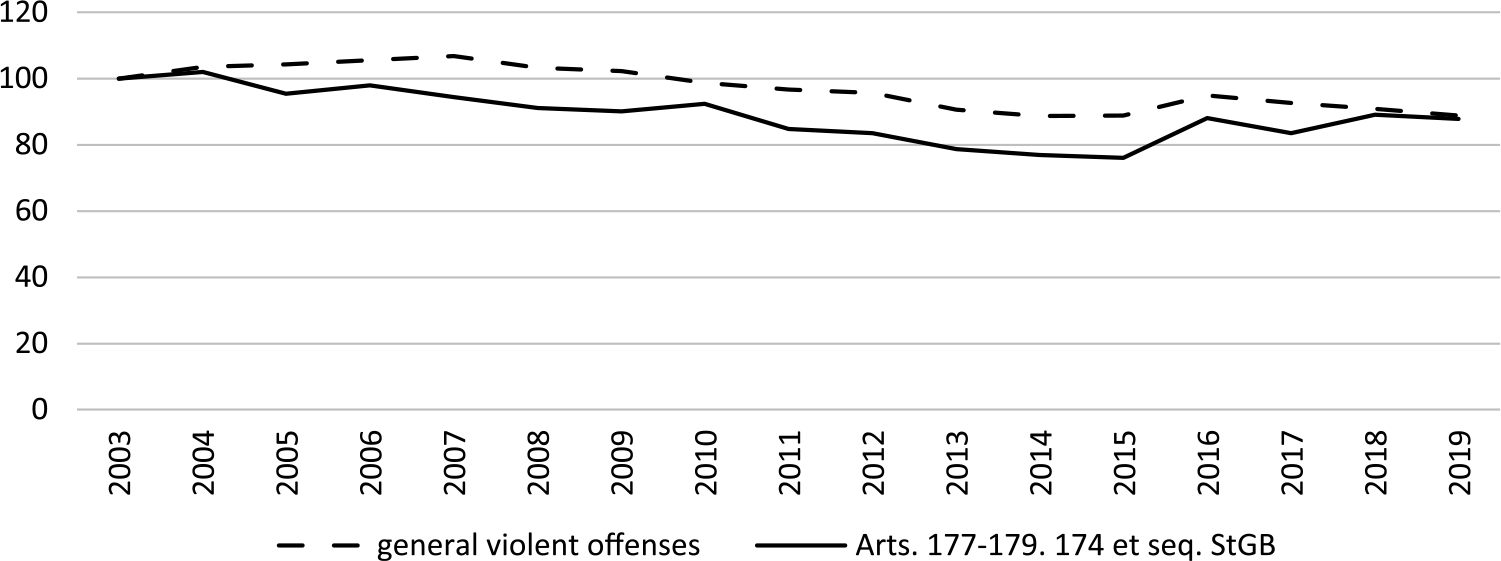

The changes shown in Table 1 concerning the frequency of cases registered by the police resemble those of the total violent delinquency until 2015. When checking the annual numbers recorded in the police statistics for the percentage above or below the situation in 2003, there is widespread convergence of the two relative trends (Figure 2). The number of registered cases is on the decline in the long term for both groups of offenses, although this trend is somewhat stronger and has an earlier onset for Articles 177–179, 174 StGB. Because some victimization surveys showed a joint decline in the prevalence of the respective offense, Footnote 40 some of the reasons that determined the decline in general violent offenses Footnote 41 could in this phase have affected the developments in sexual offenses as well. But this only applies until 2015/16 because the case numbers in this group have risen somewhat more than those for general violent offenses. This trend change had already started before Article 177 StGB was revised, so it is unlikely to be associated with it.

Figure 2. Percentage change of cases recorded by the police compared to 1999. Footnote 39

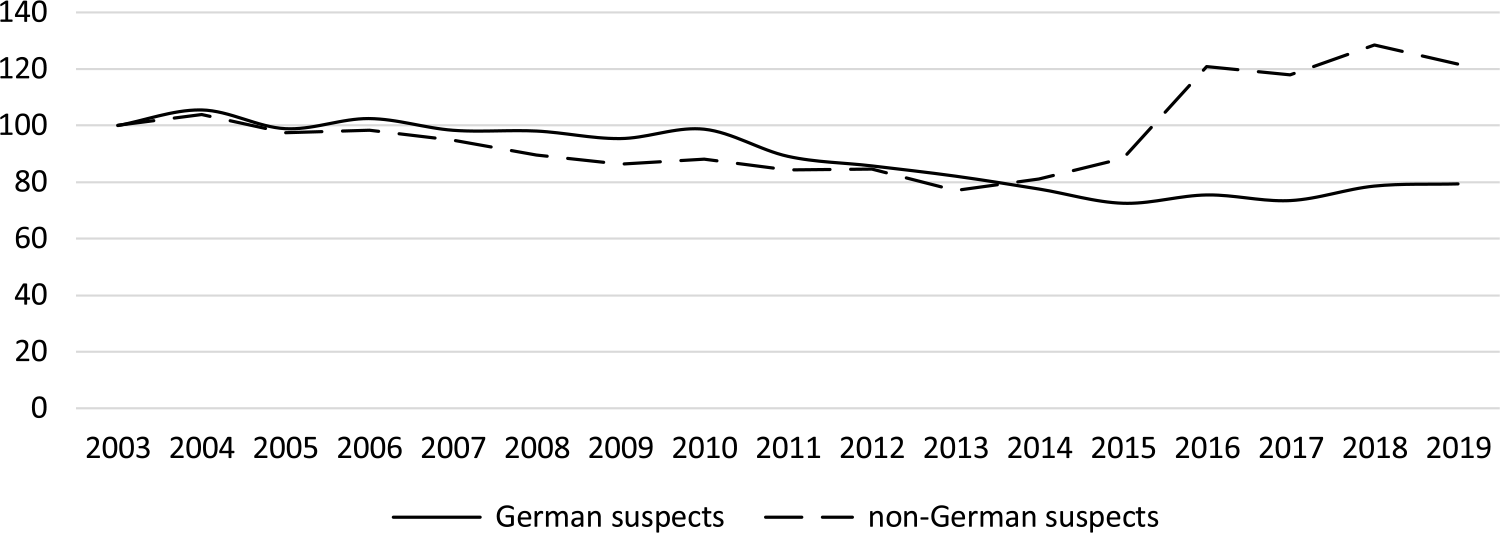

Such a timeline instead clearly indicates that the effects of the criminal law reform, as regards the numbers of cases, are significantly eclipsed by the effects the beginning migration movement had on crime statistics data in Germany. This assumption is corroborated by data on the suspects recorded by the police in this area of offenses. Starting around 2007, Table 1 shows a downward trend, both for suspects of German nationality and suspects of non-German nationality. Striking changes occurred from 2015/16. Since then, police statistics show a significant rise in non-German suspects, whereas the increase in German suspects was minor.

Figure 3 shows this based on the percentage change in the absolute number of the various suspect groups recorded annually based on the value of 2003. The visible and noticeable increase in police-recorded non-German suspects coincided temporally with the migration processes from 2015. It is, therefore, reasonable to conclude that the increase in records in the police statistics is primarily fed by the non-German population group newly immigrated from 2015 and not from the non-German population that had been residing in Germany for a longer period of time. This is also supported by the findings from detailed analyses, according to which the increase in non-German suspects can be explained by an increase by 70% in suspects who are asylum seekers and persons entitled to asylum and by an increase by 60% of suspects originating from the main countries of origin of the then migration movement.Footnote 43

Figure 3. Trends of recording German and non-German suspects (Articles 177–179, 174 StGB) Footnote 42

II. Changes in the Criminal Prosecution Persistence?

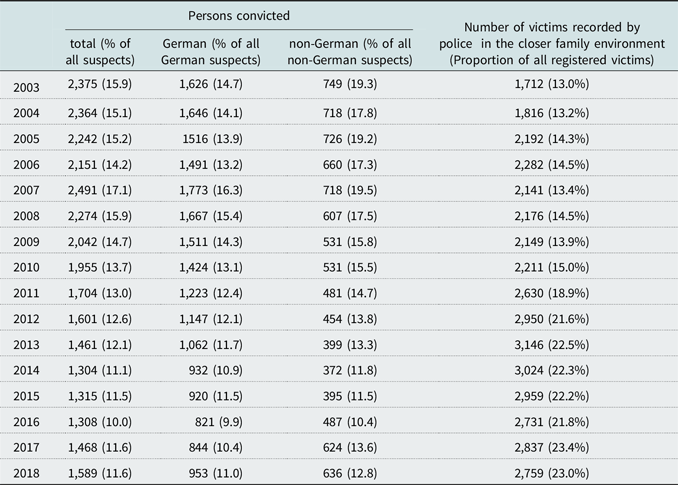

All in all, the recently recorded, and very moderate, increase of the case numbers in official statistics almost exclusively goes back to the growth of the non-German population. At the same time, the general stability of the number of German suspects indicates that the restructuring of Article 177 StGB had very little effect. By the way, the consequences of this new legislation for the sanctioning rate, which can be determined, with some restrictions, from comparing the numbers of suspects to the numbers of convictions were similarly low. The modifications of criminal law in Article 177 StGB did also not trigger a new trend in this respect (Table 2).

Table 2. Conviction rates and case features, Arts. 177-179, 174 et seq. StGB:Footnote 46

The frequency of convictions for the sexual offenses summarized here has declined in the last decade. Even after 2016, the incidence level from ten years ago is by far not reached. The increase that can be observed here is even smaller than for the suspected cases recorded by the police. In the FRG, the average for 2017/18, 1,528, was, in fact, about 34% below that of 2003 to 2006, 2,316, and about 3.7% below that of 2009 to 2016, 1,586. Accordingly, the rate of convictions is also dropping in the long term, and this has not changed more than slightly after 2016. District attorneys and the courts considerably selectFootnote 44 among the cases and suspects registered by the police, as in many other legal systemsFootnote 45—and this practice continues, tendentially even more so than ten to twenty years ago. One reason for the continuously high degree of filtering must be the frequency of cases which are difficult to prove and which can be assigned to Article 177 StGB only based on police practice, but not when applying judicial standards. This is supported by the high and likely increasing significance of events within the family, Table 2, in which the difficulty of proof is elevated—delayed reporting, a lower willingness to testify, and an ambivalence of what happened.Footnote 47 In addition, file analyses at the international levelFootnote 48 and for the Federal Republic of GermanyFootnote 49 have shown that, in particular, the procedural behavior of real or alleged victim witnesses—contradictions and gaps while making statements, withdrawals, and refusal to give evidence—is decisive for many acquittals and terminations of proceedings.

D. An (Interim) Review of the German “No Means No” Model

Politicians have hailed the revision of Article 177 StGB as a “milestone” for the protection of sexual self-determination and as a “great moment for the parliament.”Footnote 50 On the basis of the observations outlined here, this rhetoric significantly misses the real facts. As far as the quality of the legislative process is concerned (B.II. above), it was an ad-hoc legislative act. In the course of the legislative procedure, a particular parliamentary group cleverly took advantage of the public outrage triggered by the events of New Year’s Eve in Cologne to implement the regulatory model that feminist interest groups had demanded. For the sake of this objective, they also made remarkable concessions and were willing to meet the conservative governing parliamentary groups with regard to making stricter rules for expulsion. Thus, the legislative procedure was predominantly based on a political deal and much less so on a societal consensus or a balanced and differentiated debate. Of course, such a procedural shortcoming is not necessarily accompanied by a deficit in content. The revised Article 177 StGB may well be a much-welcomed legislative product. But things are anything but clear when it comes to its advantages and use. Even the regulatory intentions that led to the revision of Article 177 StGB (B.III. above) were largely missed.

There is so far no evidence that the willingness to file a police report is on the rise. This does not only contradict the aspired “activation effect,” but also a “criminalization effect” (C.I. above). The crime statistics data do not provide any indication of a number of events in which the individuals affected had suspended their need for penalties until 2016 and had not reported the incident because it was not punishable then. That the so-called protection gapsFootnote 51 which were closed by the extension of Article 177 StGB were such types of situations society had, as it were, “waited” for to become punishable and which were now fed into the criminal law system in a noticeable magnitude cannot (yet) be confirmed. It must, therefore, be questioned, based on the data analyzed herein, if a need for regulation existed that went beyond particular cases.

The same applies when looking at institutional selection, which results in significantly stronger filtering of suspected cases under Article 177 StGB than for other offenses. The trend, according to which the high proportion of proceedings ending with acquittals and terminations is even growing, was at best halted by the change in law, but not reversed (C.II. above). Apparently, the specific case structure has remained untouched by the legal changes, notably the difficulty to prove and unambiguously categorize the event. Likewise, when looking at the “enforcement effect,” the expectations regarding the “no means no” provision have been rather disappointed.

But the revision of Article 177 StGB may be legitimized by other effects, though. For example, the proponents of the “no means no” model had repeatedly equated its introduction with an unspecified “socio-political signal.”Footnote 52 This probably implied numerous interconnected messages: A threat having a deterrent effect, an emphasis on the rules of integrity-preserving, respectful sexual interaction, and in particular a symbolic solidarization with individuals affected by an offense. Thus, it was assumed that the knowledge of the punishability of unwanted sexual contacts helped the victims, even if punishment was not forthcoming.Footnote 53 However, it is completely unclear whether these messages were received by their “addressees” and effect the desired outcome—an increased preventive effect and/or enhanced coping with a crime. Of course, this cannot be falsified based on the data used here. Because no other studies are available either, both the claiming and denying such a “signal” effect remain speculation. It is currently highly vague, whether and to what extent the German “no means no” provision has changed anything or even improved things on the empirical level.Footnote 54

The same is true for the regulatory use, which may be claimed on a solely normative level in the form of increased legal coherence. In Germany, reference is made in this context to the equal treatment that has been achieved because Article 177 StGB criminalizes certain behaviors like comparable other forms of behavior which are already punishable.Footnote 55 In another variant, the emphasis is on the protection of human dignity to be ensured—and granted by Article 177 StGB— because this is compromised as a result of any disregard for sexual self-determination.Footnote 56 But this is convincing only based on specific premises. The first variant requires that criminal law without loopholes should be preferred to a fragmentary criminal law.Footnote 57 The second variant needs to take into account that human dignity does not have a factual correlate. Dignity is an attribution. How it is characterized and what constitutes an injury to it (“treatment as an object”) must, therefore, depend on a factual intersubjective consensus which cannot simply be assumed with regard to sexual self-determination, particularly when it comes to all forms of also minor impairment. Overall, therefore, the gains in “normative correctness” are rather diffuse.

E. Consequences for the Notion of a “Progressive” Criminal Policy

First, the new Article 177 StGB represents the entanglement of actors advocating women’s rights in a questionable political process (Section B.II.), and second, it is hardly legitimized by its diffuse regulatory utility (Section C.I.). In addition, the German “no means no” provision reveals that the concept of achieving a “progressive” social policy with criminal law must be problematized.

I. Ambivalence of Criminal Law

Even if criminal law were to cause something desirable, there is another side to this. The fact that it is a matter of course nowadays—and the difficulty to imagine a functioning modern society without it—cannot obscure the fact that in its reality and practice, it is also unjust and dysfunctional. This is due in part to the fact that it narrows complex events to singular acts and simple responsibilities. To a criminal court, it is solely relevant what the penal provision requires, whereas the real conflict, the history of the event, the respective contributions by those involved, their mood and subjective condition, the fabric of motivations, interactional dynamics, and the aftermath are meaningless for assessing the act. As every criminal ruling simply ignores an infinite plurality of relevant chains of events, the event of the offense is construed as the sole consequence of a free decision made by the perpetrator.Footnote 58

The reality of criminal law is, in addition, characterized by numerous coincidences as well as interests and considerations by complainants, witnesses, police officers, prosecutors, and judges far from the law. The selection of cases that are ultimately punished has passed an unimaginable number of interpretations and selection steps, all based on different standards separated from the law and in this respect neither “just” nor “appropriate.” Which of the events that could be punished in principle actually are punished, is determined by a variable fabric of numerous psychological, interactional, cultural, and institutional factors.Footnote 59 The implementation of the law is marked in such a manner that the produced results can by no means be explained based on the original regulatory intent, but based on a conglomerate of often extra-legal conditions. This takes the practical application of a penal provision, no matter what the intended goal of its enactment, into a direction of its own and at any rate different from the regulatory intention.Footnote 60

Furthermore, criminal law is unjust and dysfunctional when looking at the legal consequences for the fact alone that its penalties typically have scattering effects and knowingly include individuals who are not involved. This includes innocent individuals such as family members not affected by the offenses.Footnote 61 Financial penalties, in addition, have a socially selective effect because their repressive effect varies with the financial capacity of the addressees, which becomes ever clearer with the degree of individual poverty.Footnote 62 And imprisonment primarily consists of removing fundamental expressions of human existence. At its core, imprisonment means the creation of existential suffering: Deprivation of freedom, forced social contacts, elimination of sexuality, comprehensive regulation of daily routine, prison food, restricted consumption, media and cultural deprivation, and much more, and last but not least a dangerous living environment.Footnote 63 It should be just mentioned here in passing that all this can develop criminogenic effects.Footnote 64

II. The Tunnel Vision in the Concept of “Progressive” Criminalization

Where criminal law is introduced, it is always implemented with these downsides as well. But such aspects are typically absent from the discussion of legal policy. This was the same during the push for the “no means no” model. In fact, the argumentations of women’s associations, politicians, and their scientific supporters used an idealized version of criminal law which limits and grants freedoms of the citizens. Such a line of argumentation not only feigns the effectiveness of a penal law-based distribution of freedoms, but also the absence of collateral effects. According to this logic, more criminal law leads to more protection or prevention of harm. But as a matter of fact, more criminal law also entails more criminal law practice—this means more reductionist attribution of responsibility, unjust and uncontrolled selections, and dysfunctional interventions into the everyday world. But this was not addressed, considered, and weighed.Footnote 65 The “no means no” model is instead based on a criminal law that is cleaned of its dark facets, which does not exist anywhere in social reality.

It is comprehensible when it is intended to forcefully prevent the sexual disregard of a “no.” But if this is meant to be achieved by means of criminal law, its structural ambivalence comes into play—a fundamental ambivalence, which has to be included in the criminal policy considerations and must not simply be ignored. This is maybe too much to expect from parliamentary and media debates which are characterized by theories of everyday life. But it could be assumed that at least scientific works systematically reflect all aspects of the demanded criminalization, including adverse effects and not just its alleged utility. The tunnel vision is particularly telling in the interest groups involved, which originally pursued emancipatory concerns and to this day do not see themselves as closely aligned to the state. But the assertion of the German “no means no” provision shows how these movements, in their “progressive” endeavor to change the institution of criminal law and make it more gender-appropriate, are changed themselves. While these groups had initially questioned criminal law as a repressive mode of ruling, they are now entangled in it. The movement takes over the logic of criminal law as part of “progressive” criminalization, instrumentalizes it, and makes it its own maxim. But while its criminal policy zeal reproduces the order, functioning, and downsides of criminal law, its original identity is lost, particularly in its legislative successes.

F. Conclusion: The Current Situation—A Non Liquet

The fact that the introduction of the “no means no” rule has revealed an “indecent” political style and a one-eyed view of criminal law will hardly interest anyone in the social discourse. Instead, the so far low effectiveness of the “no means no” provision may lead to dissatisfaction and spark critical debates. The absence of a criminalization and activation effect (B.I. above) will likely be criticized because the issue of a pronounced “dark figure of crime” continues to exist.Footnote 66 This kind of critique is based on the opinion that, in case of a sexual offense, a report to the police was typically desirable. But if the conceivable benefits an affected individual can obtain through reporting the sexual assault—being able to better cope with the offense due to criminal prosecution—would outweigh reasons for not reporting the crime is just as unclear as the question of whether the social benefit of reports to the police—prevention of a new offense by penalizing the perpetrator; deterring effects of punishment—exceeds the disadvantages of criminal law (D.I. above). There is also uncertainty as to how extensive this dark field indeed is. The findings of victimization surveys, which for Germany show a one-year prevalence between 0.1% and 1.0% of respondents Footnote 67 and a lifetime prevalence in the lower two-digit percentage range or lessFootnote 68 definitely cannot be understood as an “objective” reflection of “reality.” This is based on the fact that the information collected as a subjective interpretation of the situation, “feeling of victimization,” does not necessarily coincide with the interpretation by the other party involved and/or judicial categorization of the event.Footnote 69 All in all, it should be avoided to utilize the uncertain knowledge available on the dark figure for scandalizing gaps in criminal prosecution.Footnote 70 Instead, a neutral assessment of the development of criminal charges is indicated.

Irrespective of this, selection processes require closer analysis, also because of their regionally quite varying structure. Footnote 71 However, until this is clarified, it is not appropriate to mark the considerable filtering out per se and indiscriminately as a shortcoming, as is already done by the common criminological term “attrition rate.” The implicit equation of a suspected offense and a proven act requiring punishment rarely does justice to the ambiguity of many accusations.Footnote 72 Particularly, the condemnation of judicial selection as a “justice gap”Footnote 73 reveals an astounding imbalance. Starting from an idealized victim image and a generalized non-ambiguity of the course of events, the “attrition rate” is considered a flaw of a justice system that deprives the affected individuals of the justice they are entitled to. But it remains unmentioned to what extent the justice system results in justice gaps on the other side of the relationshipFootnote 74 and how the “attrition rate” is a sign of a respective precaution of the rule of law. The erosion of the Blackstone ratio,Footnote 75 which is subjected to heated public discourse,Footnote 76 is thus carried over to the scientific discourse.