Introduction

Cyprus is an island in the Mediterranean Sea where English has the status of the most popular and important foreign language (Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015) and the majority of its inhabitants are literate in English. While a former British colony, it is generally absent from discussions of places where English has had some special relevance due to historical, political, social and economic reasons. For example, while other small countries with a history of British rule, such as Malta and Seychelles, are part of Crystal's (Reference Crystal2003: 62–5) list of English speakers in territories where English has had special relevance, Cyprus is absent from that list. This paper aims to fill this gap in the literature by providing an overview of the use of English in various domains, i.e. workplace, education, linguistic landscape, the media, and communication between Greek Cypriots, along with a brief historical background. The latter aims to illustrate how Cyprus was different from many British colonies and how this has affected the status of this language in this setting both now and during the colonization period.

The history of the English language in Cyprus dates back to 1878 when Britain took over the administration of the island from the Ottoman Turks. Cyprus remained part of the Ottoman Empire until it was annexed by Britain in 1914. It became a Crown colony in 1925 and gained its independence 35 years later, but some parts of Cyprus (the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia) remained British sovereign territory. The official languages of the newly proclaimed state became Greek and Turkish, which are the languages of the two main communities of the island. The official language of the Sovereign Base Areas is English.Footnote 1 From as early as 1963, the tension between the two main communities of the newly formed state materialized in a series of events which led to the Turkish military invasion in 1974. Due to the military occupation of the northern part of Cyprus that followed, there has been a de facto partition of Cyprus since then. As Figure 1 illustrates, Cyprus is a divided island. The part of Cyprus north of the UN buffer zone is the occupied area that is under the Turkish Cypriot administration. The area south of the UN buffer zone is that which is under the control of the Republic of Cyprus and where Greek Cypriots live. This is the area this article focuses on.

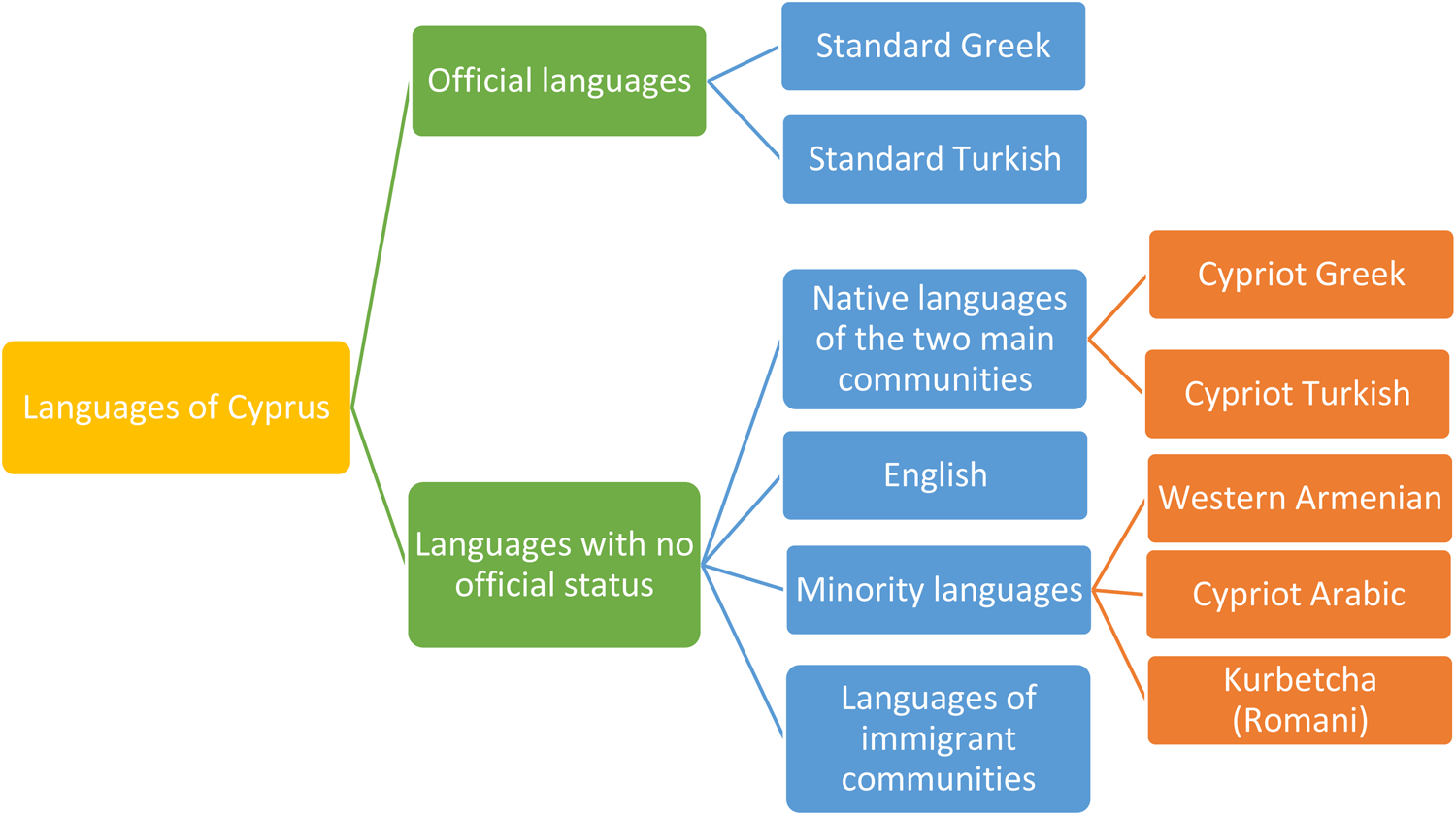

Despite its small size, Cyprus is a very rich place sociolinguistically. Apart from English and the two official languages mentioned above, there are other languages that comprise its sociolinguistic profile (see Figure 2).Footnote 2

Figure 2. Languages of Cyprus

When it comes to English, there are some studies on English in Cyprus in the literature, many of which are consulted in this paper. One of the most recent and comprehensive studies is Buschfeld (Reference Buschfeld2013), which mainly investigates whether there is a new variety of English in Cyprus (i.e. Cyprus English) and concludes that there is not. Buschfeld also examines the status that English has in Cyprus today and claims that it ‘can neither be categorized as a second-language variety (ESL), nor as a typical learner English (EFL)’ (p. 11). She argues that at the moment English in Cyprus is undergoing a ‘reversal from ESL to EFL status’ (ibid.). However, in another study on the status of English in Cyprus, Tsiplakou (Reference Tsiplakou2009) claims that ‘the historical evidence strongly suggests that it cannot be plausibly argued that [ . . . ] English was ever a second language on the island’ (p. 76). The brief historical overview provided in this paper and a more comprehensive discussion in Fotiou (Reference Fotiou2015) also point in this direction, i.e., that English was never an ESL on the island.

Besides work on the status of English in this country, there have recently been quite a few studies on the use of English as a form of borrowing and codeswitching in interactions between Greek Cypriots (Papapavlou, Reference Papapavlou1994; Goutsos, Reference Goutsos2001; Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2011; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015, Reference Fotiou and Molina Muñoz2017a, Reference Fotiou2017b, Reference Fotiou2018, Reference Fotiou2019, Reference Fotiou, Chondrogianni, Courtenage, Horrocks, Arvaniti and Tsimpli2020; Armostis & Terkourafi, Reference Armostis, Terkourafi, Ogiermann and Blitvich2019). These studies show that the use of English in Cyprus in the form of borrowing and codeswitching is not as extensive as some would argue. This shows how ‘accusations’ of extensive use of English by Greek Cypriots in their everyday speech are unsubstantiated. This is not unrelated to ‘the construct of Cyprus as an ESL country [since the latter] goes hand in hand with phobic reactions towards the alleged threat posed by English for Greek on the island’ (Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009: 84).

A brief history of English in Cyprus

According to Buschfeld (Reference Buschfeld2013), Cyprus is best characterized as an exploitation colony. There was a small number of British settlers on the island whose ‘interest was mainly of instrumental, power-political nature’ with no aim ‘to impose the British language and culture on the native population’ (Buschfeld, Reference Buschfeld2013: 200). Cyprus also differed from many British colonies in that the society was not segregated into tribes or castes, and Western education was not deemed a danger to its composition (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006: 61–2). While in many other British colonies, the missionaries founded schools before the arrival of the British governors or took control of education afterwards, in Cyprus neither of these happened because the majority of Cypriots were Christians (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006: 67).Footnote 3 As Morgan states, ‘the fact that it was not possible to convert the “natives” and bring about religious salvation undermined one of the ideological cornerstones of British imperialism’ (Reference Morgan2010: 13–14).

When the British arrived in Cyprus in 1878, there were two main ethnic and religious communities, i.e. the Orthodox Greek and the Muslim Turkish. During the British colonization period, these two very distinct communities, differing ideologically, religiously and ethnically, fought to retain their identity intact from both the colonizers and from each other; in fact, for both communities preserving their ethnic language was important for securing their identity and survival (Karoulla–Vrikki, Reference Karoulla–Vrikki2004). As such, the English language was mainly seen as a danger to the two communities’ ethnic identity and realization (Georgiou, Reference Georgiou2009; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015).

At the same time, communication between the British and the native populations was generally limited (Persianis, Reference Persianis1996: 48). While English was the official language of the colonial government, the Greek and Turkish varieties were used by the native populations, and governmental translators would translate any documents into English for the British officials. Crucially, the requirement for translators shows that the people of Cyprus were not ‘competent in English and that English did not function as a lingua franca’ (Karoulla–Vrikki, Reference Karoulla–Vrikki2004: 22).

The use and influence of English in education was also limited, at least before the island officially became a British colony in 1925. Cypriot scholars divide the British educational policy on the island into two periods, i.e. 1878–1931 and 1931–1960. The first is a period of relative laissez-faire (Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009) during which Britain's intervention in education was minimal. Greek students received Greek education and Turkish students received Turkish education and they were supported financially by Greece and Turkey (Varela, Reference Varela2006: 204). The British considered the two communities to be religious communities; thus, the latter had educational freedom under the Elementary Education Act of 1870 (Persianis, Reference Persianis2003: 355). This was a misconception on the part of the British since they had not realized that their differences were not just religious (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006).

Towards the end of the first period, things began to change. In 1923, education came under the control of the colonial government, while, in 1929, teachers became civil servants appointed by the Governor (Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2008: 5). In October 1931, massive riots broke out with Greek Cypriots demanding enosis, i.e., union with GreeceFootnote 4, during which the Government House was burnt down. This marked the onset of the second period of British educational policy during which measures were taken to diminish the ‘power’ of the Turkish and Greek languages. For example, in 1932, it became obligatory for teachers to know English in order to get promoted, while the curriculum of 1935 introduced the teaching of English in the last two grades of primary school. In the curriculum of 1949, the teaching hours of English increased, and it was taught on a trial basis from the fourth grade of primary school (Polidorou, Reference Polidorou1995: 94–8). In secondary education, English became a compulsory course both in Greek and Turkish state schools. Moreover, English language qualifications were required in order to be hired as a civil servant and for teachers’ promotion.

All these occurred while Cyprus was developing economically. During this period, many schools were founded whose main aim was the teaching of English (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006). The British government indirectly promoted the English language by offering scholarships to British universities for Cypriots who would then be appointed in high positions as civil servants. A British university degree was required for freelancers, and from 1936 onwards for lawyers too (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006). As a result, the English language and culture acquired prestige: by acquiring the language, one could have a better living and a higher social status (see Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009).

To conclude this section, the particular characteristics of Cyprus as a colony and the existence of two communities who fought to retain their identity intact from the colonizers and from each other (Karoulla–Vrikki, Reference Karoulla–Vrikki2004) played a decisive role in restricting the power and influence of the English language on the island. Despite that, the British administration succeeded in promoting the English language indirectly by making sure that acquiring English meant personal progress and social advancement (see Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009). Thus, even though English was abolished in primary schools upon the island's independence due to its perceived threat to the Greek language (Persianis & Polyviou, Reference Persianis and Polyviou1992: 150–1), and as a means to show the change of the political situation (Polidorou, Reference Polidorou1995: 102), four years later steps were taken to reintroduce it.

English in Cyprus today

English in education

For the vast majority of Greek Cypriots, English language acquisition is school-based (Buschfeld, Reference Buschfeld2013: 34). Exceptions to this may be Greek Cypriot children for whom one parent is a native speaker of English or of another language, and English is the language of communication in the house – although in many such cases it is often observed that the non-Greek-speaking parent learns Greek.

In state education, English is taught from as early as the first year of primary school, while it is also common for children to attend private English language schools in the afternoon. In private education, the model of the English ‘grammar school’ was proven effective for the social mobility of the young and was expanded after the end of British colonization (Persianis, Reference Persianis2006: 93). With the creation of English-based elementary and, more recently, nursery schools, the English language has consolidated its position on the island. Further, while the main language of instruction in the three state universities is Greek, there are now many private universities on the island where English is either the sole language of instruction or is used alongside Greek. British universities are also a favourite destination of Greek Cypriot students (Karyolemou, Reference Karyolemou2001: 30). As an indication, in the academic year 2010–2011, approximately one-fifth of Cypriot students studied in the UK (Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015). It remains to be seen how these figures will change after Brexit.

English in the media

There are quite a few media outlets in Cyprus that produce English-only content, such as radio stations and newspapers. English-speaking movies and TV series are not dubbed into Greek; they are offered with Greek subtitles. English is also used in the form of codeswitching in print media whose (main) language is Greek. A study conducted by Fotiou (Reference Fotiou2017b) showed that while such use is limited, English is found in prominent places in the print media – usually in magazine titles and headlines – and it serves a variety of discourse functions. More specifically, it is used because it symbolizes progress, success, cosmopolitanism, and exclusivity, and because it indexes knowledge and association with specific domains which are internationally expressed and circulated in English (Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2017b: 23). Interestingly, in a similar study conducted in Greece (Seiti & Fotiou, Reference Seiti and Fotiou2022), which focused on Greek fashion magazines, the form and discourse functions of English in the Greek fashion magazines shows very similar patterns of use and functions. Since Greece was never a British colony, this demonstrates how the use of English in some domains may have nothing to do with a country's colonial past but with the status that English has nowadays worldwide.

English in the linguistic landscape

English is also the most prominent language in the Cypriot linguistic landscape (LL). In the LL of two of the busiest streets in the capital of Cyprus, Nicosia, signs that are entirely in English account for 38% of the total number of signs, while those entirely in Greek come second at 20%. The rest of the signs are multilingual, while signs exclusively in languages other than Greek and English amount to just 4.6% (Karoulla–Vrikki, Reference Karoulla–Vrikki, Tsantila, Mandalios and Ilkos2016: 154). In a tourist street in Limassol, the second-largest urban area after Nicosia, 60% of the signs are in English, while just 6% are in Greek; the remainder are multilingual signs or monolingual signs in other languages (Kuznetsova–Eracleous, Reference Kuznetsova–Eracleous2015). Finally, a more recent and comprehensive study which focused on the main shopping streets and highway billboards in six areas in Cyprus (Nicosia, Limassol, Larnaca, Agia Napa, Pafos, and Troodos) confirmed that the most popular choice in the Cypriot LL is the monolingual sign in English at 63% (Karpava, Reference Karpava2022).

English in the workplace (public sector)

As Buschfeld (Reference Buschfeld2013: 200) points out, ‘when in 1960 the island was released into independence, the English language was deeply rooted in the major domains of public life’. Replacing English with the official languages of the state was not an easy task. According to the Zurich Agreement (1960), public servants working before 1960 were to be kept in their posts. This resulted in the preservation of the English language as a means of communication in public administration and the government. It was not until the mid-1980s that legal measures were applied to replace English with Greek in various sectors of public administration and government (Karyolemou, Reference Karyolemou2001). Eventually, in 1994, the Council of Ministers voted for the establishment of Greek as the official language in all governmental and semi-government organizations (Pavlou, Reference Pavlou2010).

English in the workplace (private sector)

Cyprus’ economy is dominated by services in tourism, finance, and real estate. The service sector accounted for 83.4% of Cyprus’ GDP in 2019 (CYSTAT, 2020). So, while measures were taken to remove English from the state machinery, the nature of the economy suggests that English is used in the private sector of business and industry (Davy & Pavlou, Reference Davy and Pavlou2001: 213). This is also confirmed in a recent study conducted by Theophanous (Reference Theophanous, Ioannidou, Katsoyannou and Christodoulou2020). English is widely employed in places where foreign employees work, such as offshore companies, hotels, and firms that cooperate with foreign investors.

The use of English in interactions between Greek Cypriots

The final section of this paper is dedicated to the linguistic processes of codeswitching and borrowing. Most Greek Cypriots are speakers of at least three linguistic varieties – Standard Greek (SG) and English which they learn at school, and Cypriot Greek (CG) which is their native language. As such, codeswitching practices involving English and the two Greek linguistic varieties are not unexpected.

In fact, Greek Cypriots have been accused of ‘destroying’ the Greek language because they supposedly heavily mix it with English in their communication with each other (Ioannou, Reference Ioannou1991; Αληθεινός, Reference Αληθεινός2018). Until recently there have not been many empirical studies on this topic. However, now we have a clear understanding of the nature and extent of codeswitching between Greek and English in the Greek Cypriot community. It has been shown that codeswitching practices are not extensive, contrary to what language purists believe (Goutsos, Reference Goutsos2001; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015, Reference Fotiou2019). As far as the nature of codeswitching in this community is concerned, it mainly takes the form of noun or noun phrase insertions in an otherwise CG grammatical frame (Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015, Reference Fotiou2019). Two examples are given below, with English insertions given in italics:

(1) zun mesa se celifi, se shells pu peθamena snails

‘They live inside shells, in shells of dead snails’ (cited in Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2019: 1370)

(2) en eçis ute overtʰaim ute allowances ute night stop allowances ute dress allowances tipote.

‘[You] have neither overtime, nor allowances, nor night stop allowances, nor dress allowances, nothing’ (cited in Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2019: 1371)

Further, an interesting linguistic construction, which has been characterized as a potential codeswitching universal (Edwards & Gardner–Chloros, Reference Edwards and Gardner–Chloros2007: 74), is frequently used in this community, too: the so-called Bilingual Compound Verbs. These are periphrastic verbal constructions which involve a Greek light verb, mainly the verb kamno ‘do’, which bears the required grammatical inflections and another part, usually an English uninflected verb, which bears the semantic load of the construction (Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2018). An example:

(3) en tuti pu kamniFootnote 5 usiastika drive to force

‘This is what essentially drives the force.’ (cited in Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2018: 10)

Finally, as expected, there are borrowings from English in the Greek varieties spoken in Cyprus (see Papapavlou, Reference Papapavlou1994) such as ράνταπαουτ, πάρκινγκ, κομπιούτερ, and λοκντάουν borrowed from roundabout, parking, computer, and lockdown, respectively. Of particular interest are borrowed politeness discourse markers from English to Cypriot Greek such as sorry, thank you, and please which are used along the Greek politeness markers but bear different discourse functions (Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2011; Armostis & Terkourafi, Reference Armostis, Terkourafi, Ogiermann and Blitvich2019; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou and Molina Muñoz2017a). However, it should be noted that English borrowings into Cypriot Greek are limited in number in comparison to borrowings from other languages.

Final remarks

This paper aims to fill a gap in the literature concerning the use and status of English in Cyprus which is, perhaps surprisingly, a neglected case of a former British colony in the literature of English around the word. The brief historical overview on the use and presence of English on the island during the colonization period suggests, in agreement with Tsiplakou (Reference Tsiplakou2009), that English was most likely never a second language on the island.

In Cyprus today, English is not an official language but the most popular and important foreign language (Tsiplakou, Reference Tsiplakou2009; Fotiou, Reference Fotiou2015). It is a language present in a variety of domains of use to various degrees, not only because of the country's colonial past, but also because of the nature of its economy and the role that English plays as the global lingual franca.

DR CONSTANTINA FOTIOU is a sociolinguist and an English language teacher and trainer. She holds a PhD and an MA in Sociolinguistics. She is currently a Visiting Lecturer at the Department of English Studies of the University of Cyprus. She has presented her work in a number of international and local conferences and published a number of papers in peer-reviewed journals. She is a member of LAGB, IATEFL, MATSDA and the Assistant Secretary of the Cyprus Linguistics Society (CyLing). Email: fotiou.constantina@ucy.ac.cy

DR CONSTANTINA FOTIOU is a sociolinguist and an English language teacher and trainer. She holds a PhD and an MA in Sociolinguistics. She is currently a Visiting Lecturer at the Department of English Studies of the University of Cyprus. She has presented her work in a number of international and local conferences and published a number of papers in peer-reviewed journals. She is a member of LAGB, IATEFL, MATSDA and the Assistant Secretary of the Cyprus Linguistics Society (CyLing). Email: fotiou.constantina@ucy.ac.cy