The traditional narrative of the history of the cello has placed the origins and early developments of this instrument in the vibrant centres of the Emilia region.Footnote 1 Scholars have focused their attention on the activity of the earliest cello virtuosi and composers – such as Domenico Gabrielli (1659–1690), Giovanni Battista Degli Antonii (1660–1696) and Giuseppe Maria Jacchini (1667–1727) – and on the existence of a substantial printed repertory for the cello in Bologna and Modena.Footnote 2 This approach has often overlooked the early developments of the cello in other Italian centres and the significant contribution of other traditions to the evolution and dissemination of this instrument.Footnote 3

Sparked by a renewed interest in the importance of instrumental music in Naples,Footnote 4 recent studies have established the central role of Neapolitan virtuosi in the dissemination of a solo repertory for the cello and the advancement of its technical resources in the eighteenth century.Footnote 5 There is no doubt that the exceptional success of a group of virtuosi – such as Francesco Alborea (1691–1739), Francesco Paolo Supriani (1678–1753) and Salvatore Lanzetti (c1710–1780), who were trained in the Neapolitan conservatoires and then served in the major Italian and European courts – crucially contributed to the dissemination of the modern cello, to the standardization of tuning and holding, and to the advancement of performance practice.Footnote 6 Yet the history of the early development of the cello in Naples remains largely unwritten. If we know that Neapolitan conservatoires started to hire specialized cello teachers only around the mid-eighteenth century, it is evident that the virtuosic Neapolitan tradition did not emerge abruptly. The remarkable progress of the Neapolitan performers originated in a tradition of training and performance that was already well established in the city by the end of the seventeenth century.

A hitherto neglected source provides new insights into the cultivation and progress of the cello repertory in seventeenth-century Naples. As it includes the earliest and largest local repertory dedicated to bass-violin instruments, this manuscript collection occupies a significant place in the history of the cello. It sheds light on the solid pedagogical tradition developed in Naples, revealing its emphasis on improvisation and extemporaneous composition, and offers a rare view of the characteristics and uses of the early cello in the Neapolitan area. The remarkable historical significance of this manuscript is amplified by the inclusion of two unknown cello sonatas by Giovanni Bononcini (1670–1747), which constitute the only surviving works for ‘violoncello’ solo by this celebrated composer.

In order to give a proper appreciation of the significance of this source, I first describe its structure and codicological features, then provide information on the careers of the composers included in the volume; finally I examine the characteristics of the instruments used, features of performance and teaching practices, the function of this repertory and the place of such music in the history of the cello in seventeenth-century Naples.

THE MANUSCRIPT

The manuscript MS 2-D-13 is a large homogeneous volume in oblong quarto (measuring 21 by 27.5 cm) preserved in the Biblioteca dell'Abbazia di Montecassino (I-MC).Footnote 7 The volume consists of one hundred and thirty-six folios bound together in thirty-four numbered gatherings; it includes fifty-one works (plus a single anonymous movement), most of them unica. Table 1 shows the full content of the collection. The ex-libris on the inside of the cover indicates that the volume belonged to Vincenzo Bovio, a nineteenth-century organist and master of ceremonies at the Abbey of Montecassino and priore at the church of San Severino in Naples.Footnote 8 Although the history and exact provenance of the manuscript are unknown, codicological evidence points to Neapolitan origins. Two watermarks appear in the source. The most frequent is a fleur-de-lis inscribed in a circle, a watermark commonly found both in Roman and Neapolitan sources of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The second one depicts a quadruped inscribed within a circle, surmounted by the letter P; in some volumes of cantatas this watermark is associated with the printer Giovanni Palmiero, active at least from the first decades of the eighteenth century at Porta Medina in Naples.Footnote 9

Table 1 Contents of manuscript MS 2-D-13, Biblioteca dell'Abbazia di Montecassino

The manuscript is still preserved in what was probably its original binding. Some page edges appear to have been slightly cut to fit it. The elegant leather cover (Figure 1), complete with two clasps, bears the title ‘Sonate’ on the spine, while front and back are richly decorated by a golden emblem representing two crenellated towers on water. This coat of arms belonged to the Di Somma family, one of the oldest and most influential among the Neapolitan aristocracy.Footnote 10 No documentary evidence connects this family to the repertory included in the volume or to music patronage in general in the seventeenth century, but it is certainly plausible that some members of the family sponsored musical activities or commissioned copies of instrumental music for their private use.

Figure 1 Manuscript from the Biblioteca dell'Abbazia di Montecassino (I-MC), MS 2-D-13. Cover with the emblem of the Di Somma family. All figures are taken from this manuscript, unless otherwise indicated, and are used by permission

The collection appears to be the work of a single scribe, written in careful handwriting and showing very few erasures or mistakes. The year 1699, specified on both the title-page and the last folio of the manuscript, provides the terminus ante quem for the composition of these works. We can assume that the entire manuscript was copied to order, possibly having been compiled from various works that had been written in different years, but all belonging to roughly the same time.Footnote 11

As is apparent from Table 1, two collections by Rocco Greco (1657–c1717) form the bulk of the manuscript, placed as bookends at the beginning and end of the volume; they enclose another collection of a Neapolitan composer, the ten passacaglias by Gaetano Francone (fl. 1688–1717). The inclusion of the two sinfonie per violoncello by the Modenese Giovanni Bononcini therefore represents a striking exception in this otherwise entirely Neapolitan source.

The only anonymous work in the whole manuscript is a short 3/8 binary movement entitled Balletto. Despite sharing the same key with the preceding sonata by Bononcini, its style and part-writing are certainly unrelated to that work. Some of its characteristics seem rather to relate to Rocco Greco's sonatas. The function of this isolated movement remains unclear, especially considering the overall arrangement of this source.Footnote 12

THE COMPOSERS

The largest part of the Montecassino manuscript consists, as noted, of works by two Neapolitan composers, Rocco Greco and Gaetano Francone. Although almost forgotten today, Greco and Francone were among the leading figures on the Neapolitan musical scene of the late Seicento.

Born in 1657, Rocco Greco came from a family of musicians: his father, Francesco, had been a wind-instrument teacher (‘maestro di cornetta’) at both the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini and at the Poveri di Gesù Cristo in the second half of the seventeenth century.Footnote 13 The most prominent member of the family was certainly Rocco's younger brother, Gaetano. Both brothers studied at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo,Footnote 14 but while Gaetano, as maestro di cappella at the Poveri di Gesù Cristo from 1696, became a respected and influential teacher of counterpoint – among his students there were Giuseppe Porsile, Nicola Porpora and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi – Rocco pursued a career as a string performer and teacher. In 1677 Rocco was hired at the Conservatorio dei Poveri as a teacher of string instruments, and in 1698 he joined the ranks of the Royal Chapel. He was one of the governors of the Congregazione e Monte dei Musici in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore, the largest and most powerful guild of musicians in Naples.Footnote 15 On 28 August 1687 the governors of the Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro appointed Greco to replace Paolo Antonio d'Oria (also known as Sessa) as ‘prima viola’, specifying in their motivation that Greco was ‘the best [player] nowadays in Naples, acclaimed as such by all the music virtuosi’ (‘il migliore ché sia hoggi in Napoli, acclamato per tale da tutti li virtuosi di musica’).Footnote 16 The records of the Tesoro di San Gennaro confirm Rocco's participation in all the major celebrations and festivities of that institution up to 1717. Already three years earlier, however, the governors’ minutes had mentioned that Greco had been forced to miss several events owing to illness. On 20 April 1717, since he had already been ill for some time, the governors of the Tesoro finally decided to replace Greco with Francesco Alborea, who would also be officially hired as a ‘violoncello’ player in the event of Greco's death.Footnote 17 As this is the last document mentioning Rocco Greco at the Capella del Tesoro, his death must have occurred shortly thereafter.

The career of the violinist Gaetano Francone overlaps in part with that of Greco. Although we have relatively little biographical information on this musician, archival records show that Francone was employed from 1688 as string teacher at the Conservatorio di Sant'Onofrio, where he had Francesco Durante among his students.Footnote 18 His name also appears in the list of violinists employed in the five main festivities of the Casa Santa dell'Annunziata.Footnote 19 Like Greco, Francone was elected as governor of the Congregazione e Monte dei Musici. In 1689, however, a diarist mentions that he had been expelled because he had participated in a performance at the Teatro dei Fiorentini, thus contravening the strict rule that prohibited musicians enrolled in the Congregazione from playing in public theatres.Footnote 20 On 12 June 1697 Francone joined the chapel of the Tesoro di San Gennaro as first violin in the ‘second choir of the instruments’ (‘Secondo Coro degli strumenti’).Footnote 21 This ‘virtuoso, renowned for his thorough talents’ (‘virtuoso conosciuto d'ogni habilità’) served that chapel until 1717: a despatch of the Governors on 25 May 1717 announced Francone's replacement following his death.Footnote 22 The ten passacaglias included in the Montecassino manuscript are Francone's only known compositions.

The two sinfonie per violoncello by Giovanni Bononcini are a major addition to the catalogue of this celebrated musician and contribute significantly to our understanding of an overlooked aspect of his career. Although scholarly attention has mostly focused on his successful vocal production, contemporary accounts attest that Bononcini was one of the greatest cello virtuosi of his time. The Diario Bolognese of 1776 clearly called attention to both these aspects of his training:

sotto la disciplina di Gio. Paolo Colonna apprese Gioanni [sic] l'arte del contrappunto e dalla scuola di D. Giorgio Buoni apprese l'arte di sonare il violoncello, nelle quali due arti si rese così eccellente, che fu ammirato e commendato per tutta l'Europa.

under the discipline of Giovanni Paolo Colonna, Gioanni [sic] learned the art of counterpoint, and from the school of D. Giorgio Buoni he learned the art of playing the violoncello. In both those crafts he became so excellent that he was admired and praised throughout Europe.Footnote 23

Bononcini's precocious talent as a performer and composer of instrumental music was admired throughout his long career. By 1687 he had already published six instrumental collections – from the Trattenimenti da camera, Op. 1, to the twelve Sinfonie a due, Op. 6 – which certainly contributed towards securing him an early admission to the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna. In December of 1686, ‘being skilled on any string instrument’ (‘avendo abilità per qualsivoglia istromento da arco’),Footnote 24 Giovanni entered the service of the Cappella di S. Petronio as a violinist, and later as a cello player in Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili's orchestra. Nicola Haym, who had played with him in Rome, considered Bononcini ‘indisputably the first’ among cello virtuosi.Footnote 25 Writing in 1716 about the most famous Italian composers of cantatas, John E. Galliard associated Bononcini's talent as a composer with his competence as a cello player: ‘Of late years, Aless. Scarlatti and Bononcini have brought cantata's to what they are at present; Bononcini by his agreable and easie style, and those fine inventions in his basses (to which he was led by an instrument upon which he excels)’.Footnote 26

Despite such extensive and prestigious activity, only one work for cello has thus far been attributed, tentatively, to Giovanni Bononcini.Footnote 27 Moreover, the correct attribution of Bononcini's music has often been difficult owing to the overlapping of the parallel careers of Giovanni's younger brother, Antonio Maria – who was also a renowned cello virtuoso – and of his father, Giovanni Maria. The two works included in the Montecassino manuscript are therefore extremely significant as they provide insights into Bononcini's style and technical capabilities as well as into the type of instrument he played.Footnote 28

GIOVANNI BONONCINI'S SINFONIE PER VIOLONCELLO

In the Preface to his Méthode pour apprendre le violoncelle, published in Paris in 1741, Michel Corrette stated:

Depuis environ vingt-cinq ou trente ans, on a quitté la grosse basse de Violon montée en Sol pour le Violoncelle des Italiens, inventé par Bonocini [sic] présentement Maitre de Chapelle du Roi de Portugal, son accord est d'un ton plus haut que l'ancienne Basse, ce qui lui donne beaucoup plus de jeu.Footnote 29

About twenty-five or thirty years ago we [French] gave up the larger basse de violon tuned in G [B♭1-F-c-g] in favour of the violoncello of the Italians, invented by Bonocini [sic], presently Chapel Master of the King of Portugal; its tuning is a whole tone higher than the old basse de violon, which gives it much more versatility.

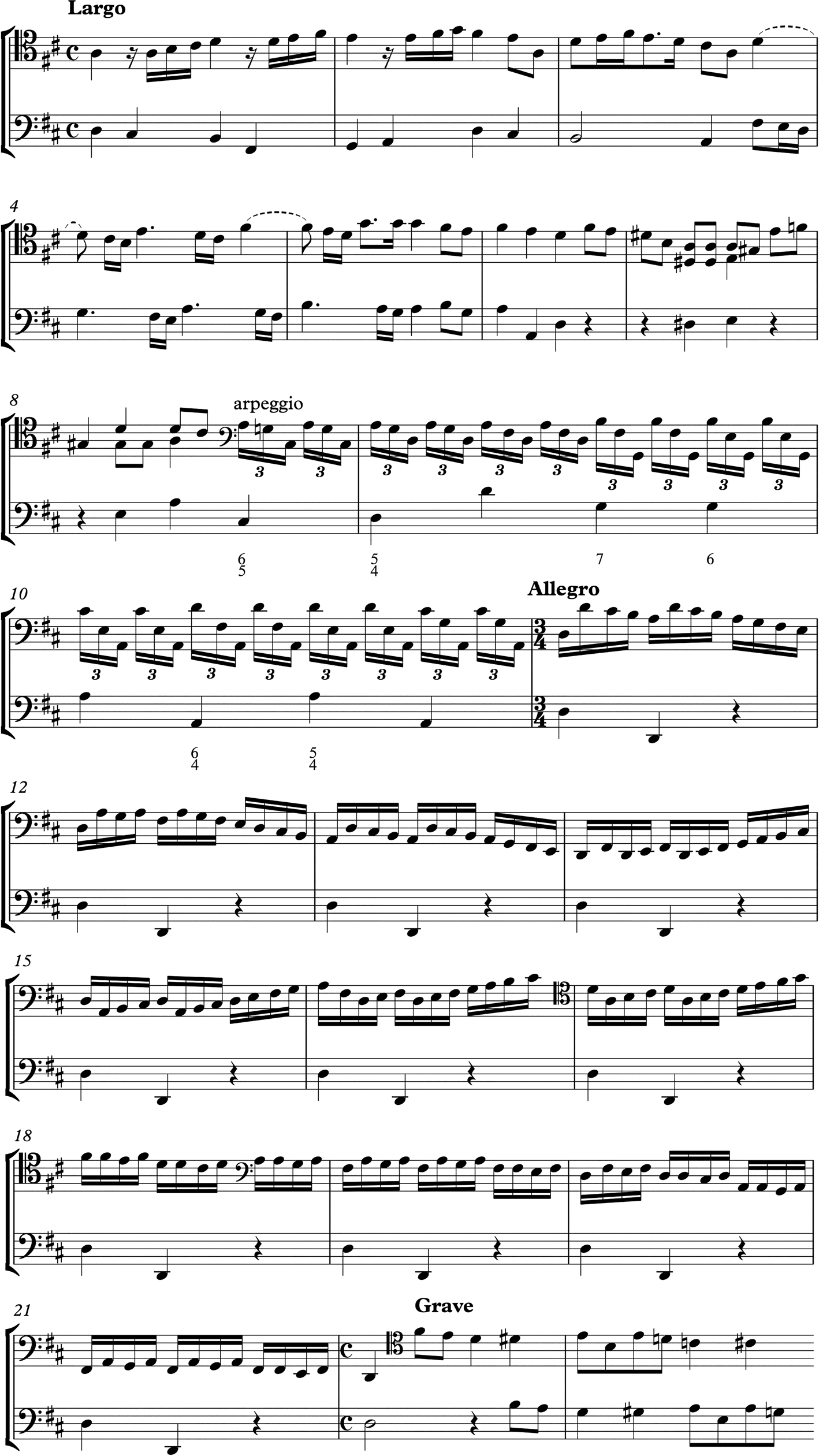

Corrette's account confirms the fame achieved by Bononcini as a virtuoso player – going so far as to make him the inventor of the ‘violoncello’ – and gives a succinct description of the new instrument. The technical features of the two Montecassino sonatas present compelling evidence concerning the characteristics of this instrument. Both works are divided into four movements, with a regular alternation of slow and fast tempos: the opening, multi-sectional movement of the first sinfonia (Example 1) starts with a short Corellian Largo that establishes the key; it is followed by a section in ‘arpeggio’ and then by an Allegro in triple metre, filled with batteries Footnote 30 and fast semiquaver runs over a tonic pedal, after which the movement ends with a Grave. The juxtaposition of contrasting sections and prevalence of solo passages lends the entire movement a brilliant, quasi-improvisatory quality and links it to the late seventeenth-century stylus phantasticus.

Example 1 Giovanni Bononcini, Sinfonia per violoncello (No. 1), first movement, bars 1–23. Biblioteca dell'Abbazia di Montecassino (I-MC) MS 2-D-13, fols 59v–60. All examples are taken from this manuscript, unless otherwise indicated, and are used by permission

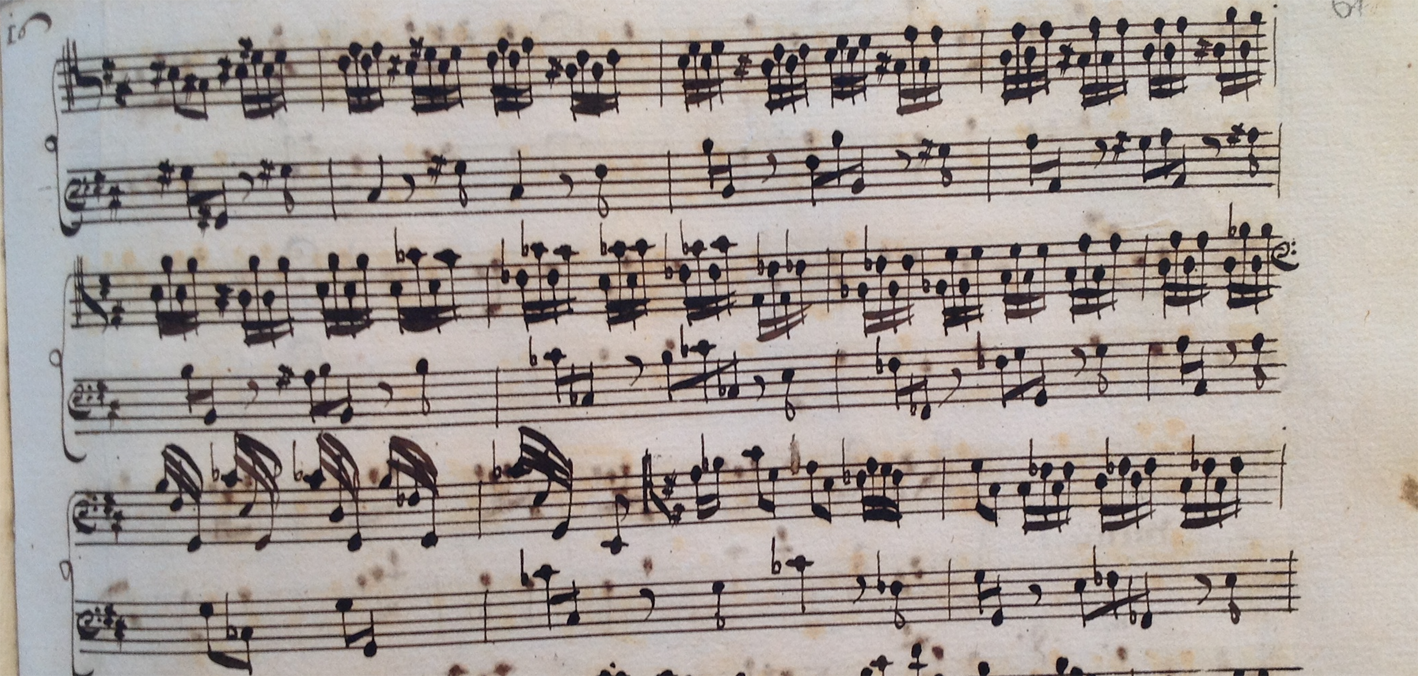

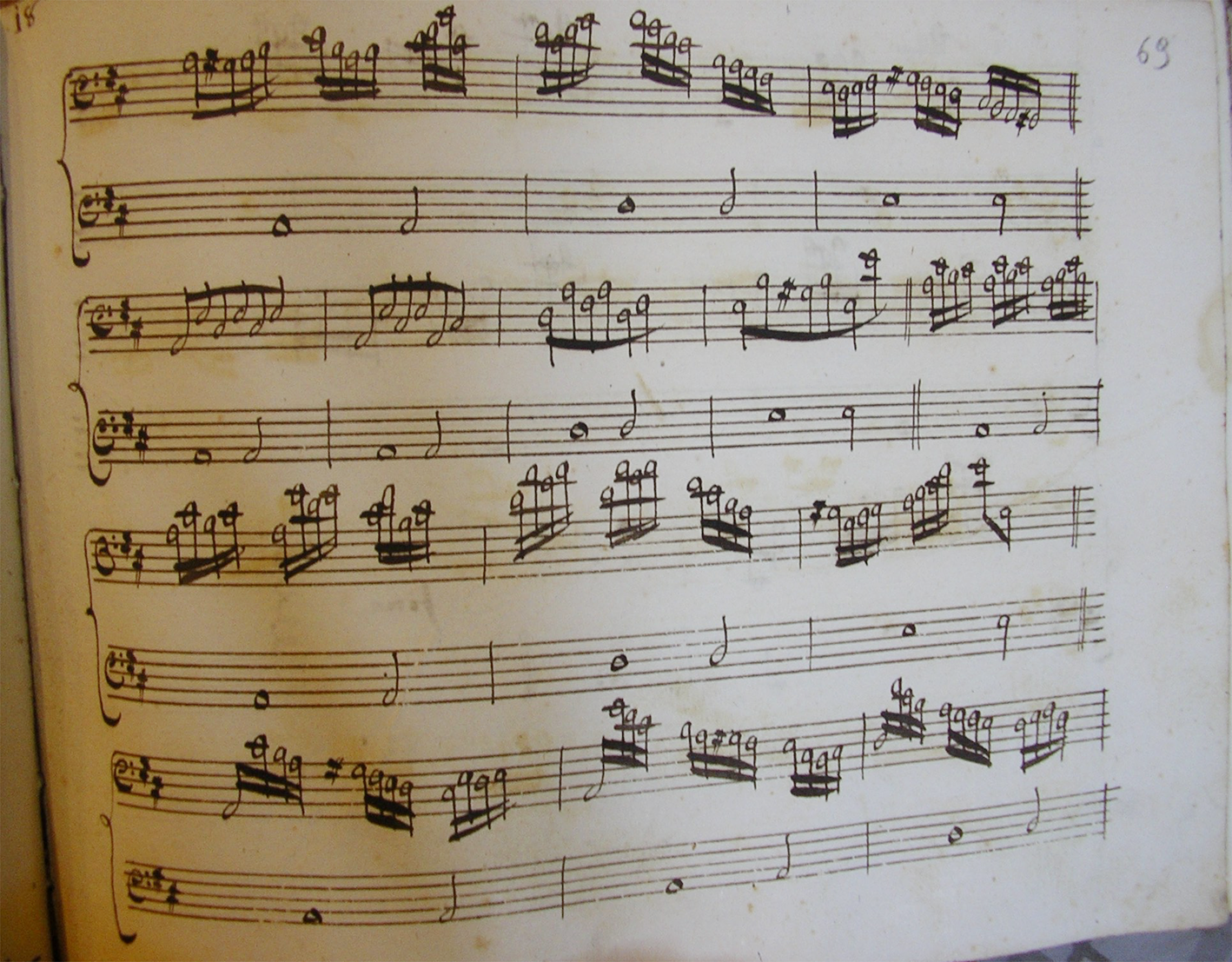

Similar technical demands and improvisatory writing also mark sections of the second movement, Allegro (Figure 2). A compact dialogue between the two parts is achieved through frequent recourse to imitative exchanges, cadential unisons or sections in parallel thirds, the latter featuring prominently in the second sinfonia (Example 2). Passages like these provide indications of the full compass of the instrument and idiomatic techniques, and confirm that these sonatas were conceived for an instrument similar to the one described by Corrette. In fact, in the third paragraph of his Preface, Corrette adds:

Le Violoncelle est beaucoup plus aisé a joüer que la basse de Violon des anciens, son patron étant plus petit, et par consequent le manche moins gros, ce qui donne toute liberté pour joüer les basses difficiles, et même pour executer des pièces qui font aussi bien sur cet instrument que sur la Viole.Footnote 31

The violoncello is much easier to play than the old basse de violon, since its size is smaller and consequently the neck is thinner, which gives complete freedom to play difficult basses, and also to execute pieces that work as well on this instrument as on the viol.

Figure 2 Giovanni Bononcini, Sinfonia per violoncello (No. 1), second movement, bars 18–27 (fol. 61)

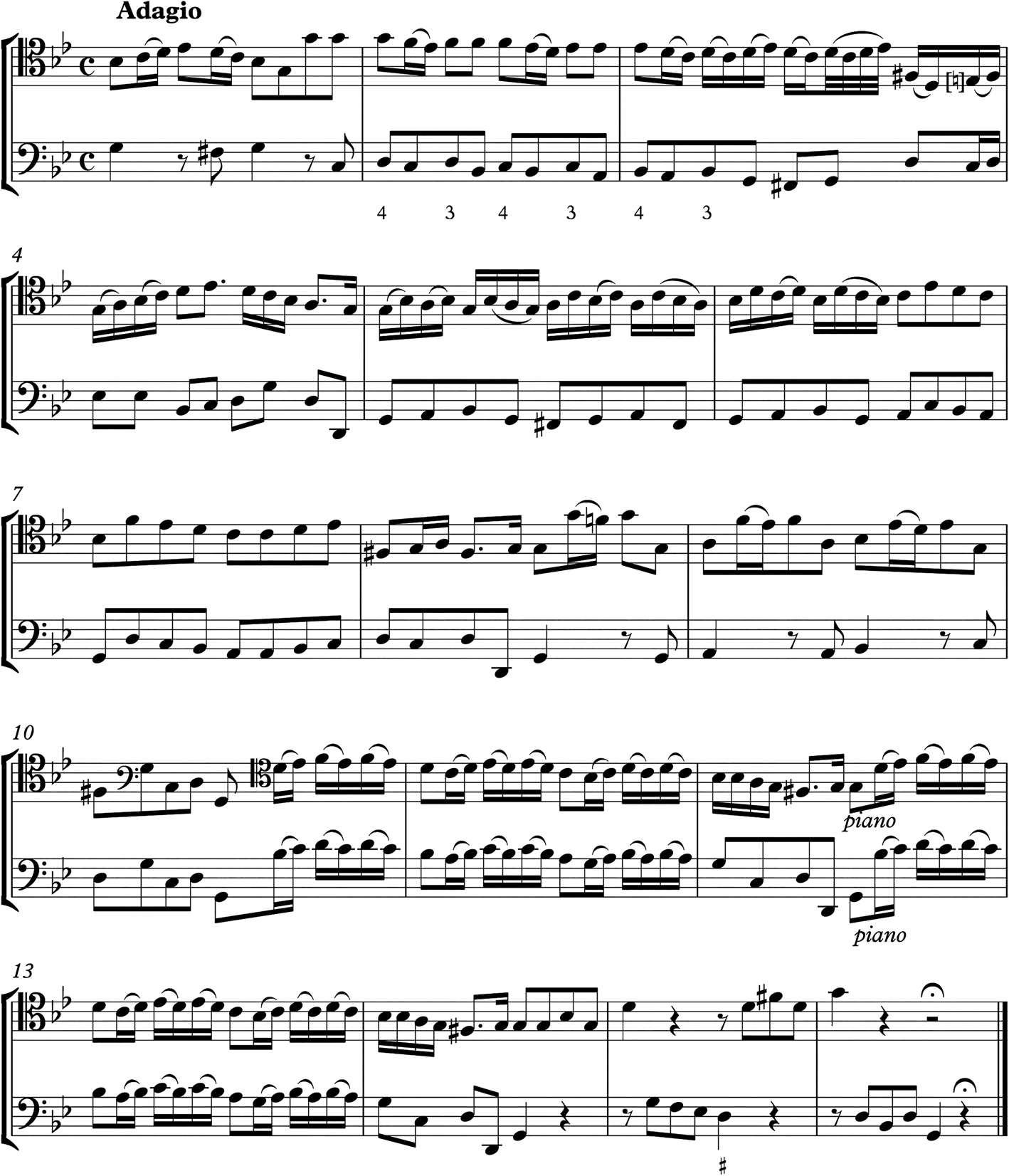

Example 2 Bononcini, Sinfonia per violoncello (No. 2), first movement (fol. 62)

The solo part of the Montecassino sonatas, written mostly in the tenor clef, spans from D to a1, the highest note in the entire manuscript. Its idiomatic writing strengthens the hypothesis that Bononcini's ‘violoncello’ was a four-string instrument, in all likelihood smaller than the modern cello and tuned C-G-d-a, or possibly with a lower string tuned a step higher (D).Footnote 32

The style of these two sinfonie stems from the virtuosic tradition in which, as we have seen, Bononcini had been raised. They show the influence of the solo repertory developed by cello players of the northern Italian school, virtuosi such as Domenico Gabrielli or Giuseppe Jacchini, active in Bologna and at the Este court in Modena in the second half of the seventeenth century.Footnote 33 The two sonatas also feature the more markedly galant language that Bononcini adopted and developed over the course of his career. The cantabile manner found in the slow movements of the second sinfonia and in the minuets that end both sonatas illustrates perfectly Bononcini's ‘agreable and easie style’,Footnote 34 a quality that emerges even when, as in the minuet of the first sonata (Example 3), phrase overlaps and cadential echoes generate irregular seven-bar strains.

Example 3 Bononcini, Sinfonia per violoncello (No. 1), fourth movement (fol. 61v)

Similar traits can be observed in Bononcini's violoncello obbligato arias included in the oratorios and serenatas he wrote in Rome for Lorenza Colonna.Footnote 35 The two Montecassino sonatas are indeed connected to Bononcini's Roman years and to his early activity as a vocal composer. Around 1691 Bononcini entered the service of Filippo and Lorenza Colonna and started his productive collaboration with the poet and librettist Silvio Stampiglia. This partnership resulted in the creation of some of the composer's most celebrated operas and serenatas; it was the fame reached through these Roman productions that opened the doors to Bononcini's future international career.Footnote 36

The most successful among these early works was certainly Il trionfo di Camilla regina dei Volsci, premiered in Naples at the San Bartolomeo Theatre on 27 December 1696. The opera was a homage to Lorenza Colonna's brother, Luis Francisco de la Cerda, Duke of Medinaceli, to celebrate his appointment as the new Spanish Viceroy of Naples. Camilla soon became an international triumph: ‘twenty-three productions in Italian cities from 1698–1719; three in London (in English translation) from 1706–1728; as well as countless books of favorite arias’.Footnote 37 The account in the Gazzetta di Napoli attests to the extraordinary success of this work and confirms that Bononcini's fame as a cello player preceded that as an opera composer:

Con grandissimo plauso continuasi nel Teatro di S. Bartolomeo la recita dello scritto dramma nomato Il trionfo di Camilla, composto dal sig. Silvio Stampiglia e posto egregiamente in musica dall'eccellente sonator di violone sig. Giovanni Bononcini bolognese, essendosi finora rappresentato tredeci volte con infinito concorso, onorato quasi ogni sera dall'intervento di questi eccellentissimi viceregnanti.Footnote 38

The performances of the drama entitled Il trionfo di Camilla, written by Sig. Silvio Stampiglia and admirably set to music by the excellent violone player Sig. Giovanni Bononcini of Bologna, continue to be performed to great applause at the San Bartolomeo Theatre, having been so far presented thirteen times before a large audience, and honoured almost every night by the presence of the Most Excellent Sovereigns of this realm.

Although there is no documentary evidence of the presence of Bononcini in Naples, it is certainly possible that the composer attended the celebrations arranged for the Duke of Medinaceli and, as it was customary, supervised the first rehearsals and performances of Il trionfo di Camilla. Bononcini's close connections with the Neapolitan milieu are in fact confirmed by an announcement that circulated a year earlier, according to which the composer would have replaced Scarlatti at the helm of the Neapolitan Royal Chapel, an appointment that never materialized:

Si ritrova in Roma il celebre Alessandro Scarlatti per passare in Spagna maestro di cappella di sua maestà cattolica e Giovanni Bononcino [sic] altro celebre par suo passerà in Napoli maestro di Cappella di quel signor viceré.Footnote 39

The famous Alessandro Scarlatti is in Rome on his way to Spain to become maestro di cappella of His Catholic Majesty, and the equally famous Giovanni Bononcino [sic] will move to Naples to become maestro di cappella of that Viceroy.

If the two sonatas included in the Montecassino manuscript were brought to Naples by Bononcini (or if they were expressly composed for and sent there), we can date them to between 1691 and 1697 – more precisely, to around the year that saw the production of Il trionfo di Camilla. Certainly, they had already been written by August 1697, when, following the sudden death of Lorenza Colonna, Bononcini moved to Vienna. In fact, the bass part in arias such as ‘Dall'idol mio’ in Il trionfo di Camilla, although not expressly indicated for the ‘violoncello’, features passages as elaborate as those found in the Montecassino sonatas.Footnote 40

The adoption and rapid dissemination of the ‘violoncello’ in Naples finds concrete evidence in the repertory written by Alessandro Scarlatti and other Neapolitan composers in the 1690s. Scarlatti's ‘Se la gioia non m'uccide’ in the oratorio Giuditta (1693) is among the earliest examples of arias with obbligato ‘violoncello’ (range D–g1) by this composer, while in the third act of Il prigioniero fortunato, an opera performed in Naples in 1698, and so chronologically very close to the Montecassino source, Scarlatti included an aria ‘col violoncello’, ‘Luce degl'occhi miei’.Footnote 41

The presence in this collection of the two sinfonie by Giovanni Bononcini becomes, therefore, particularly significant as a testimony to the gradual replacement of the old bass violin by the new, smaller ‘violoncello’, and the latter's rapid rise to favour among the Neapolitan virtuosi. They also indicate the impact, via the Roman milieu, of the northern Italian cello tradition on the developments of the Neapolitan school. These innovations were probably driven by the frequent musical exchanges between Naples and Rome and the activity of Roman musicians, such as Alessandro Scarlatti and the influential Roman string teacher Giovanni Carlo Cailò, who moved with Scarlatti to Naples in the 1680s.Footnote 42

‘VIOLA’ AND ‘VIOLONCELLO’ IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES

Bononcini's works for the ‘violoncello’ constitute an exception in the Montecassino manuscript. Large parts of the repertory in this source in fact document a transitional stage in the development of bass-violin instruments in Naples. The collection that opens the manuscript bears the title Sonate à due viole ‘del Sig.r Rocco Greco / 1699’. These twenty-eight sonatas – individually entitled Sinfonia – are short pieces for the most part divided into two movements, an opening in fast or slow tempo followed by a binary-form movement in triple metre. The first movements – often without a precise tempo indication – present a variety of formal solutions and styles. Those in slow tempo are characterized by a prevalence of a melodic upper part, which highlights the instrument's lyrical qualities; in some cases, Greco adopts a style that closely recalls that of Corelli's opening Grave movements, as in the fourteenth sonata (Example 4). In other instances, as in the twentieth sinfonia, the movement takes the form of a multi-sectional prelude that alternates between fast arpeggios on tonic or dominant pedals and slower cantabile sections (Example 5). Most of the final movements are binary dances, with a preference for a corrente in 3/4 or movements in 3/8 with gigue or minuet characteristics. In two instances they are written in 3/2 with recourse to white notation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Rocco Greco, Sinfonia Viggesima Quinta (No. 25), second movement (fols 52v–53r)

Example 4 Rocco Greco, Sinfonia Decima Quarta (No. 14), first movement, bars 1–9 (fol. 29v)

Example 5 Greco, Sinfonia Viggesima (No. 20), first movement, bars 1–10 (fol. 41v)

While the idiomatic writing appears similar to that found in Bononcini's sonatas, some features of these works suggest the use of a different instrument. In Greco's sonatas – as in Francone's Passagagli – the two parts are written almost exclusively in bass clef; their tessitura extends down to B♭1, while the upper range rarely exceeds f1 (Greco's works reach g1 only occasionally). Arpeggios (often on a chord of F major) and the range of scale runs prove that these works were probably intended for a four-string bass violin tuned B♭1-F-c-g, probably slightly larger and therefore less agile than the ‘violoncello’. This tuning, encountered in the repertory of the Modenese school up to the end of the seventeenth century, is indeed the one indicated by Corrette for the ‘grosse basse de Violon’.Footnote 43 Thus in seventeenth-century Naples the term ‘viola’ was clearly used to designate a group of larger bass violins that ‘sacrificed ease of playing in favor of bass sonority’.Footnote 44 These instruments should not be mistaken for the modern alto viola – normally called ‘violetta’ in Neapolitan sources – nor with the viola da gamba, since they possessed neither the tuning nor the idiomatic writing associated with that instrument.Footnote 45

The Montecassino repertory effectively illustrates the permanence in late seventeenth-century Naples of a distinct nomenclature describing two groups of bass-violin instruments, divided according to size and function: larger instruments – with four or sometimes five strings, usually tuned B♭1-F-c-g – were designated as ‘viola’ and often entrusted with the continuo realization, while the term ‘violoncello’ was reserved for instruments most likely smaller than the modern cello, usually tuned C-G-d-a, held vertically, played with an overhand bow grip and mostly used in solo repertory.Footnote 46

The concomitant and often overlapping use of these two terms also appears in the official documents of Neapolitan institutions around the turn of the eighteenth century. In the registers of the Royal Chapel, Rocco Greco and Giulio Marchetti are still listed as players of ‘viola’ in 1708, the same year in which the term ‘violoncello’ makes its appearance in that institution in reference to the appointment of Francesco Paolo Supriani.Footnote 47 Around 1713, a list of musicians of the Royal Chapel compiled by Alessandro Scarlatti refers to Rocco Greco as a ‘player of viola in the old manner’ (‘sonador di viola all'antica’), while just two years earlier, Greco appears instead listed among the ‘violoncelli’.Footnote 48 As we have seen, he had been hired as ‘prima viola’ at the Tesoro di San Gennaro in 1687 and was replaced in 1718 by the ‘violoncello’ virtuoso Francesco Alborea. In 1711, however, Nicola Fago, maestro di cappella at the Tesoro, had already recommended that ‘fully to carry out the music of the Tesoro, a Violoncello is needed’ (‘Essendono stati richiesti dal Magnifico Nicola Fago maestro di cappella del nostro Tesoro, che per complire di tutto punto la musica di detto Tesoro vi è di bisogno il Violoncello’), and endorsed the employment of Supriani in that position.Footnote 49 A sign of this fluctuating nomenclature is in fact also present in the Montecassino source: the title of Francone's Passagagli includes the term ‘violoncello’ associated with an instrument tuned in B♭1.

A paradigmatic case of this transitional stage in the definition of bass-violin instruments is the Confitebor a voce sola con istrumenti by Gaetano Veneziano (1665–1716). Besides including two ‘violonzelli soli’ without violins in the ‘Memor erit’ section, Veneziano's Confitebor presents partbooks with the full combination of nomenclatures: parts for first and second violins, first and second ‘violonzello’, ‘viola e leuto’ playing the continuo, ‘violetta’ (that is, modern alto viola), and finally a 16′ ‘controbasso’.Footnote 50

PARTIMENTI AT THE CELLO?

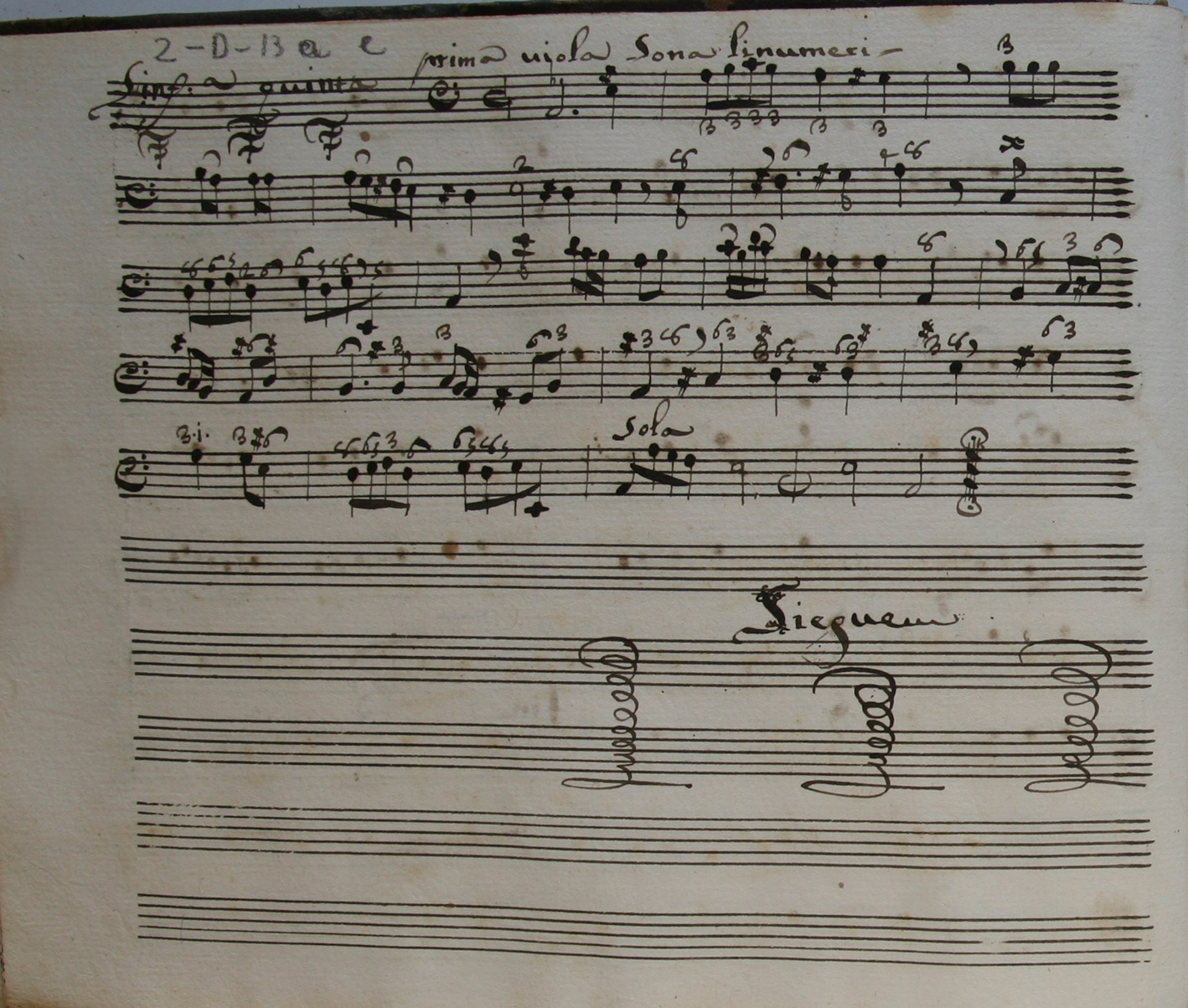

The first movements of Sinfonia Quinta and Sesta in Greco's collection present a remarkable feature: in these movements Greco wrote out only the part of the second viola and added figures above it with the instruction, ‘the first viola plays the numbers’ (Figures 4a and 4b). The figures included in these movements are not indications for continuo realization; they rather imply that the melodic part of the first viola must be obtained from extemporaneously playing the intervals provided.Footnote 51 This process of composing the upper part by improvising over figures indicated in the bass likens these two sonatas to partimento practice. Indeed, the ‘use of figures for representation of melodic lines instead of chords is one of the features that distinguish partimento from continuo practice’.Footnote 52 If in some cases the succession of numbers calls for simple parallel movements between the two parts – as does, for instance, the sequence of thirds in the second bar of Sinfonia Quinta (see Figure 4a) – other figures imply the use of more elaborate contrapuntal patterns, characterized by imitative exchanges, as shown in a sample realization derived from the figures in bars 7–9 of the same sonata (Example 6).

Figure 4a Greco, Sinfonia Quinta (No. 5), first movement (fol. 13v)

Figure 4b Greco, Sinfonia Sesta (No. 6), first movement (fol. 15)

Example 6 Greco, Sinfonia Quinta (No. 5), first movement, bars 6–9 (fol. 13v), sample realization

These examples from the Montecassino manuscript suggest that a method similar to keyboard partimento practice was known to cello players and could evidently be used in a repertory for two instruments.Footnote 53 The hypothesis of a connection between Greco's sonatas and the partimento tradition is strengthened by existing concordances between the Montecassino manuscript and one of the earliest sources of Neapolitan partimenti, the manuscript 33.2.3 held at the Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella (I-Nc). The latter is a large composite volume that on the opening page bears the title ‘Partimenti di Rocco Greco’. Although the copyist's hand differs from the one found in the Montecassino source, two notes confirm Rocco Greco's authorship, at fol. 21 (‘Sig. Rocco Grieco’) and fol. 25v (‘Sono del Sig. Rocco Gieco [sic]’). The manuscript opens with an incomplete copy of Greco's antiphons (discussed below), and contains about thirty figured partimenti attributed to Greco followed by ‘a series of 114 monophonic pieces, totally unfigured, in a florid instrumental style and often with dance rhythms. These pieces are among the most problematic in the whole partimento repertoire’.Footnote 54 These works, possibly exercises gathered as a student's notebook or as teaching materials, use a variety of clefs – mostly bass and tenor, but also alto and soprano – and feature the same idiomatic passages with arpeggios, scales and elaborate passagework found in Greco's sinfonie.Footnote 55

A detailed comparison and analysis of this source, which is beyond the scope of this study, could reveal the presence of several concordances, but even a few examples can demonstrate the close link between the two repertories. The opening of the last movement of sinfonia No. 28, moving from an initial cadential progression to a sequential module over a descending scale, appears as a simplified variant of the third movement of the first sinfonia, but it is also a transposed version of the incipit of Partimento 9 in I-Nc 33.2.3 (see Examples 7a–c).Footnote 56 Similarities also appear between the first bars of Partimento 89 and the second movement of Greco's Sinfonia ottava, both, in turn, related to Partimento 5 (see Examples 8a–c) as well as to some of the patterns in Example 7.

Example 7a Greco [?], Partimento 9, bars 1–15. Biblioteca del Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella, Naples (I-Nc), 33.2.3, fol. 29

Example 7b Greco, Sinfonia Viggesima ottava (No. 28), second movement, bars 1–10 (fol. 58v)

Example 7c Greco, Sinfonia prima (No. 1), third movement, bars 1–17 (fol. 3v)

Example 8a Greco, Sinfonia ottava (No. 8), second movement, bars 1–12 (fol. 18v)

Example 8b Greco [?], Partimento 89, bars 1–7. I-Nc 33.2.3, fol. 69

Example 8c Greco [?], Partimento 5, bars 1–7. I-Nc 33.2.3, fol. 27

Even if these works are not bona-fide partimenti, their inclusion in a miscellaneous volume together with keyboard intavolature and partimenti by the Greco brothers, and their concordances with Rocco Greco's Sonate à due viole, show a close proximity between the cello repertory of the Montecassino volume and the partimento tradition. It is certainly not coincidental that the Grecos belonged to the first generation of Neapolitan composers who introduced and developed partimento practice in Naples.Footnote 57

The analogy between the works in I-Nc 33.2.3 and Greco's sonatas indicates the existence of a repertory of formulas, a ‘vocabulary’ of patterns used to develop a solid competence in improvisation and contrapuntal elaboration. The instructions for the extemporaneous realization of an entire movement at the cello provided in Greco's fifth and sixth sonatas are rare, but clear, testimonies that the practice of improvised composition based on a figured bass was well known and cultivated by the Neapolitan cello players towards the end of the seventeenth century.Footnote 58

CONTINUO REALIZATION AT THE CELLO: ROCCO GRECO'S SUBSTITUTE ANTIPHONS

The close interplay between the two parts in Greco's sonatas – often characterized by tight imitative exchanges and passages in parallel thirds, as seen in the Sinfonia quarta (see Example 9) – suggests a performance by two equal instruments, obviously also implied in the title of Greco's collection (‘Sonate à due viole’). Yet the works included in the Montecassino manuscript cannot be considered just as cello duets. Although the occurrence of continuo figures is relatively sporadic – and in some instances they appear to be later additionsFootnote 59 – their presence throughout the manuscript is evidence of the practice of continuo realization at the cello.Footnote 60

Example 9 Greco, Sinfonia Quarta (No. 4), first movement, bars 1–10 (fol. 10v)

The last collection in the Montecassino manuscript shows a remarkable use of the cello as continuo instrument in a sacred context. This set of eleven liturgical compositions, bearing on the first page the indication ‘del Sig.r Rocco Greco’, is one of the earliest examples of the presence of the cello in liturgical settings, a practice that may well have been widespread in the Neapolitan environment. The textual incipits that Greco has included at the beginning of each piece reveal that these are in fact elaborations of eleven antiphons; Table 2 lists all the incipits and the corresponding feast.

Table 2 Rocco Greco's Antiphons

Each antiphon includes between two and four sections, alternating between duple and triple metres, with the exceptions of ‘Veni electa mea’ – written as a through-composed movement in 3/2 – and ‘Sacerdos Dei’, divided into five sections. A partial copy of six antiphons is also found at the opening of the manuscript I-Nc 33.2.3. Although following a slightly altered order and copied by two different hands, the I-Nc 33.2.3 and the Montecassino manuscripts share identical versions of the antiphons (see Table 3), which confirms the close relation between these two sources.Footnote 61 In fact, the source of Greco's antiphons appears to be the volume of Antifone per diverse festività di tutto l'anno by Bonifacio Graziani (1604–1664), a collection that had a wide dissemination after its posthumous publication in 1666.Footnote 62 Greco's two-part antiphons follow precisely the order of all eight antiphons ‘a due voci’ in Graziani's set, but also include antiphons ‘a tre voci’ (‘Fidelis servus’ and ‘Veni electa mea’) and ‘a quattro voci’ (‘Domus mea’). Indeed, the correspondence goes beyond the mere succession of titles: with a single exception, Greco's bass part reproduces Graziani's organ part literally. Greco follows the original antiphons so carefully that each section of his works corresponds exactly to the partitions and time changes present in Graziani's set (see Figure 5a and compare Figures 5b and 5c).Footnote 63

Figure 5a Bonifacio Graziani, Antifone per diverse festività di tutto l'anno (1666), organ part, page 6. Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica, Bologna (I-Bc)

Figure 5b Greco, Loquebantur, first section (fols 93v–94r)

Figure 5c Greco, Loquebantur, second section, bars 1–13 (fol. 94v)

Table 3 List of Greco's antiphons included in I-Nc 33.2.3

While the second ‘viola’ plays the antiphons’ bass in long notes, the first part elaborates on this bass foundation with idiomatic arpeggios, string-crossings and scales. These works are in fact examples of antiphon substitutes, or more precisely antiphon overlays, performed mainly during the Office of Vespers while the priest intoned the full text of the antiphon. The practice of interpolating or replacing the antiphons, before or after the psalms, with other vocal or instrumental music, particularly during Vesper services, became widespread in Italian churches in the second half of the seventeenth century. The Cæremoniale Episcoporum promulgated in 1600 by Pope Clement VIII recommended the organist to play between the Vesper psalms as long as someone intoned the full antiphon texts simultaneously. Collections of antiphons, such as the one by Graziani, were then published to respond to this new demand and helped establish the practice of improvisation and elaboration, usually at the organ, over the Vesper antiphons.Footnote 64 Greco's works are evidence of a practice that required cello players to replace the organist in this function or at least to elaborate together with the organ on the original antiphon bass.Footnote 65

A closer look at these elaborations reveals a crucial aspect of continuo realization at the ‘viola’. A comparison with the continuo figures of the original demonstrates that the principle governing Greco's realizations is not chordal, but it is rather based on a contrapuntal approach that privileges melodic and idiomatic elaborations and diminutions of the original bass. The approach to continuo realization at the ‘viola’ was therefore conceived horizontally and developed through the study of patterns and schemata, to be memorized in a process that blended together performance, improvisation and composition, an approach that was very close indeed to that followed by organ players in the performance of alternatim organ versets.Footnote 66 This repertory of melodic and bass patterns points to a practice and a pedagogical approach that aimed at perfecting the performers’ abilities in extemporaneous contrapuntal improvisation.

A REPERTORY FOR IMPROVISATION: FRANCONE'S PASSAGAGLI

The ten ‘Passagagli per violoncello del Sig.r Gaetano Francone’ (see Table 4) are the only known works by this musician, and represent the largest corpus of passacaglias for cello in the whole seventeenth century.Footnote 67 Although it was with the publication of Girolamo Frescobaldi's Partite sopra passacaglia in 1627 – followed ten years later by his Cento partite sopra passacaglia – that the passacaglia became widely popular in the keyboard repertory, this basso ostinato had reached Italy at the beginning of the seventeenth century through collections devoted to the rasgueado technique on the Spanish guitar.Footnote 68 Early in the century, passacaglias were ‘short formulaic progressions that presumably served as models for . . . ritornello improvisations and perhaps also as exercises for strumming common chords sequences’.Footnote 69 Francone's Passagagli indeed follow the plain original harmonic pattern (I–IV–V–I) introduced in the early guitar alfabeto tablatures. They appear more related to Giovanni Battista Vitali's set of Partite sopra diverse sonate per il violone (before 1692) based on alfabeto chords – Vitali's Bergamasca per la lettera B has the same bass pattern and features sets of elaborations similar to Francone's style – than to the geographically closer model of Andrea Falconieri's Passacalle à 3 per violini e viole (1650).Footnote 70

All ten passacaglias by Francone are in triple metre, seven in 3/4 and three in 3/2, the latter all written in white notation (Figure 6). The set presents a quite regular organization: the first eight are arranged on ascending steps of the diatonic scale, starting from G minor and using the most common keys up to two flats and three sharps, while the first four alternate between minor and major modes, though altogether we find a prevalence of the major mode, a relatively unusual choice for passacaglias.

Figure 6 Gaetano Francone, Passagaglio 2.o, bars 41–55 (fol. 69)

Table 4 List of Gaetano Francone's Passagagli

Each passacaglia presents between twelve and sixteen iterations of the bass, elaborated by the upper part over the bare harmonic pattern. Although not exceptionally virtuosic, the upper part includes a combination of idiomatic writing for the ‘violoncello’ – in this case, however, most likely a ‘viola’ given the compass from B♭1 to f♯1 – that includes string-crossing, batteries, arpeggios, octave leaps and scales, together with constantly varying articulations and rhythmic combinations (Example 10). As in Greco's antiphons, Francone's set is based on the linear elaboration of the bass pattern: each example proceeds from simple rhythmic variants to elaborate melodic divisions that, starting from the notes of the ground, embellish them through a variety of ornamental figures (scales, arpeggios, turns and sequences).

Example 10a Gaetano Francone, Passagaglio Terzo (No. 3), bars 1–16 (fol. 70)

Example 10b Francone, Passagaglio Terzo (No. 3), bars 49–65 (fols 71v–72)

Example 10c Francone, Passagaglio Sesto (No. 6), bars 33–44 (fols 78v–79)

Example 10d Francone, Passagaglio Nono (No. 9), bars 33–49 (fols 85v–86)

Example 10e Francone, Passagaglio Decimo (No. 10), bars 45–53 (fols 88r–v)

Francone's variations on the passacaglia, along with numerous other works based on a ground bass, were a crucial tool in the teaching and development of improvisation skills. In fact, the simple reiteration of this bass formula in the lower voice was particularly suited to improvisation and variations: ‘A complete set of Passacagli also presented most excellent exercises for the beginner guitarist to learn the basic chords of his instrument. Such a forthright tonal sequence seems especially fitting when the Passacaglio acts as an intonazione for a vocal piece’.Footnote 71 These improvisations over the passacaglia were in fact often used in the performance of introductions or ritornellos in strophic arias. Some examples of these improvised passacaglia ritornellos are, for instance, found in the Neapolitan copy of Monteverdi's L'incoronazione di Poppea (1651).Footnote 72 The pedagogical value of this short harmonic formula consisted in the unlimited possibilities of rhythmical and idiomatic variations that were available to the improviser, a trait that also characterizes Francone's set. Through these sets of variations, performers (often amateurs) could assimilate a stock of formulas directly through performance and apply them to a variety of repertories. The development of such competence was not only a key element in the formation of the cello virtuoso, but also the foundation of the techniques of accompaniment, an essential function of bass-violin instruments in the late seventeenth century.

FUNCTION AND DESTINATION OF THE MONTECASSINO REPERTORY

The variety of repertories included in the Montecassino manuscript raises questions about its function and destination. What conclusions can we draw about the reasons for gathering this repertory and what is its importance in the early history of the cello in Naples?

The prevalence of works intended for performance on two paired instruments suggests a pedagogical aim for this repertory. Vocal and instrumental bicinia were indeed considered very effective teaching tools in the training of two students or in master–student performances. This teaching method was frequently used in Naples: collections of duets and two-part solfeggi such as Cristoforo Caresana's Duo, Op. 1 (1681), or Gregorio Strozzi's Elementorum musicae praxis, Op. 3 (1683), are well-known Neapolitan examples of this practice.Footnote 73 Francone's elaborations on the passacaglia bass respond to a similar pedagogical goal. They provide a repertory of melodic and harmonic formulas aimed at developing a solid competence in improvisation and advancing the technical proficiency required for cello players to perform both solo and continuo repertories.

Yet the fine binding of the volume, its ordered gatherings and the clarity of the copy make this manuscript unlike any notebook of exercises jotted down for the practice of professional students or for the training of inexperienced amateur players. Rather, the care and elegance of this source indicate that it was copied to order and probably became part of a private collection, perhaps as a gift presented to an amateur performer of the Di Somma family, or instead as a florilegium of some of the most advanced works for the cello written by eminent composers at the end of the seventeenth century.

Regardless of the rationale behind the compilation of the Montecassino manuscript, this repertory offers a unique perspective on crucial aspects of cello performance practice in seventeenth-century Naples. Greco's collection of antiphons presents new evidence of the widespread and still insufficiently documented use of bass violins in liturgical settings, together with or even in lieu of the organ. This repertory also provides rare insights into the distinctive approach to continuo performance at the cello, based not on chordal realization, but rather on contrapuntal elaborations and diminutions of the bass part, often built upon idiomatic figures. This approach, which combined performance, improvisation and composition in an integrated whole, placed cello practice in close contact with the concomitant partimento tradition. The inventory of figures and formulas that this collection offers to the players gives a clear sense of the advancement of cello technique in seventeenth-century Naples and offers models that could effectively be used in the modern pedagogy of improvisation.

The exceptional significance of the Montecassino repertory for the history of the cello is undeniable. Through this source it is possible to reconstruct the transformation of bass-violin instruments in Naples between the end of the seventeenth century and the first decade of the following century, a time of transition from the ‘old-fashioned viola’ to the spread of the new ‘violoncello’. The analysis of repertories and idiomatic writing helps us to clarify not only the nomenclature and the organological characteristics of the bass-violin instruments, but also the new solo role being given to the emerging ‘violoncello’.

Finally, the Montecassino manuscript confirms the significant contribution of Neapolitan musicians to the evolution of the cello. The presence of Giovanni Bononcini's ‘violoncello’ sonatas in this source represents a finding of the utmost importance, not only because they are the only two surviving contributions to the cello repertory by this renowned composer, but also because they hint at the influence of the northern Italian cello tradition on the developments of the Neapolitan school, via the Roman milieu. The collections included in this volume reveal the roots of the extraordinary success of the eighteenth-century Neapolitan cello virtuosi and bear testimony to the central role that Naples occupied in the history of the early cello.