Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder defined by the presence of elevated levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that impair daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Comorbidity is common, and language impairments are increasingly identified in this population. Children with ADHD are thought to be at a threefold risk of comorbid language difficulties (Sciberras et al., Reference Sciberras, Mueller, Efron, Bisset, Anderson, Schilpzand and Nicholson2014), including deficits in their expressive, receptive, and pragmatic language skills (Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson, & Sciberras, Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017; Redmond, Reference Redmond2004). Despite growing awareness of language difficulties in this population, less than half of the children with ADHD and comorbid language impairments access speech pathology services, and only a quarter receive language support (Sciberras et al., Reference Sciberras, Mueller, Efron, Bisset, Anderson, Schilpzand and Nicholson2014). This is concerning given the central role of language skills in long-term functional outcomes such as literacy, employment, social relationships, and mental health (Duff, Reen, Plunkett, & Nation, Reference Duff, Reen, Plunkett and Nation2015; Hebert-Myers, Guttentag, Swank, Smith, & Landry, Reference Hebert-Myers, Guttentag, Swank, Smith and Landry2006; Law, Rush, Schoon, & Parsons, Reference Law, Rush, Schoon and Parsons2009; Matthews, Biney, & Abbot-Smith, Reference Matthews, Biney and Abbot-Smith2018; Salmon, O'Kearney, Reese, & Fortune, Reference Salmon, O'Kearney, Reese and Fortune2016).

One aspect of language of increasing interest in ADHD is pragmatics. While definitions of pragmatic language are many and varied (see Supplementary Table S1), there is a general consensus that pragmatics encapsulates the social use of language. The overarching construct of pragmatic language can be broken into constituent parts, examples of which include: conversational turn-taking, adapting the tone and content of spoken messages to meet the listener's needs, the initiation, maintenance, and termination of conversions, and producing coherent narratives (Prutting, & Kirchner, Reference Prutting and Kirchner1987; Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe, & Halperin, Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013). The pragmatic language abilities of children with ADHD have been the subject of two previous reviews (Green, Johnson, & Bretherton, Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017). Green et al. (Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014) synthesized the findings from 30 questionnaire-based, observational and experimental studies, concluding the pragmatic abilities of children diagnosed with ADHD, or with elevated levels of inattention and/or hyperactivity, are impaired relative to their TD peers. Specific difficulties were identified in conversational reciprocity, excessive talking, the production of coherent speech and possibly higher-level language comprehension. More recently, Korrel and associates (Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017) conducted a systematic meta-analytic review of language problems in children diagnosed with ADHD. They identified 21 studies that assessed the performance of children with and without ADHD on standardized or validated language measures. Relative to the controls, children with ADHD showed large deficits in expressive, receptive, and pragmatic language skills, although the analysis for pragmatic language included only four studies.

The interest in pragmatic language in children with ADHD has been driven, in part, by growing recognition of the link between pragmatic language difficulties and social impairments in these children (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014). The results of several studies highlight the association between pragmatic language and social function in ADHD, in areas such as peer relationships (Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013), likeability (Lahey, Schaughency, Strauss, & Frame, Reference Lahey, Schaughency, Strauss and Frame1984), peer rejection (Hubbard & Newcomb, Reference Hubbard and Newcomb1991), and social skills (Leonard, Milich, & Lorch, Reference Leonard, Milich and Lorch2011). For example, in a community sample, Leonard et al. (Reference Leonard, Milich and Lorch2011) found that pragmatic language use fully (hyperactivity) or partially (inattention) mediated the associations between ADHD symptoms and social skill deficits. Similarly, in a sample of children with ADHD and their TD peers, Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) showed that discourse management skills fully mediated the association between ADHD symptom severity and social skills. Together, these findings suggest that pragmatic language is closely related to both ADHD symptoms and social skills, and that a more thorough understanding of pragmatic language in ADHD may have important theoretical and clinical implications.

While pragmatic language impairments have been identified in children with ADHD, thus far, few theories have been proposed to account for why this group is vulnerable to pragmatic difficulties. One hypothesis is that impaired pragmatic language might be expected in children with ADHD as several of the core symptoms of the condition – such as failing to respond when spoken to, talking excessively, difficulty awaiting conversational turns, and interrupting or intruding on others – are synonymous with pragmatic language problems (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg, & Hendriks, Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017). Alternatively, pragmatic deficits may be a secondary consequence of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity on verbal and nonverbal communication (see Camarata & Gibson, Reference Camarata and Gibson1999, for a detailed discussion). Symptoms of ADHD have also been proposed to contribute to pragmatic language impairments by reducing the opportunities in which children are able to practice their social communication skills (Hawkins, Gathercole, Astle, Holmes, & Team, Reference Hawkins, Gathercole, Astle, Holmes and Team2016). In addition, poor social functioning in this population could be directly attributable to pragmatic language difficulties, as pragmatic language skills are critical to achieve effective social interactions (Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013). While the discourse management aspects of pragmatic language overlap with symptoms of ADHD, the skills involved in presupposition and narrative discourse may not be directly accounted for by ADHD symptoms (Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013).

Underlying cognitive mechanisms, such as executive dysfunction, and specifically, difficulties with planning, working memory, and emotion regulation, could also contribute to pragmatic language difficulties in ADHD, via both direct and indirect pathways (Blain-Brière, Bouchard, & Bigras, Reference Blain-Brière, Bouchard and Bigras2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Gathercole, Astle, Holmes and Team2016). While executive function problems are likely important for pragmatic language in ADHD, research regarding the links between executive function and the development of pragmatic language skills has yielded mixed findings (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Biney and Abbot-Smith2018), and several researchers have acknowledged the lack of specificity of this relationship (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Biney and Abbot-Smith2018). Thus, there are several possible explanations for the pragmatic difficulties in ADHD, including that they arise as a direct consequence of the core ADHD symptoms; are associated with the widely reported social difficulties of children with ADHD; and may be underpinned by executive dysfunction.

Pragmatic language problems have been observed in a range of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric conditions, including ADHD (Bellani, Moretti, Perlini, & Brambilla, Reference Bellani, Moretti, Perlini and Brambilla2011). While there is a general consensus that children with ADHD have pragmatic language impairments, which may be related to core features of the condition, thus far, we have been unable to establish whether there is a pragmatic language profile that is specific to ADHD, or whether the pragmatic difficulties observed in these children overlap with those of other neurodevelopmental conditions. One possible comparison group is autism spectrum disorders (hereafter referred to as autism), a neurodevelopmental condition that is defined by social communication difficulties. Pragmatic language difficulties have long been considered a “hallmark” of autism (Kim, Paul, Tager-Flusberg, & Lord, Reference Kim, Paul, Tager-Flusberg, Lord, Volkmar, Paul, Rogers and Pelphrey2014) and the nature of pragmatic language in autism is relatively well characterized (see Supplementary Material Table S2; Eigsti, de Marchena, Schuh, & Kelley, Reference Eigsti, de Marchena, Schuh and Kelley2011; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Paul, Tager-Flusberg, Lord, Volkmar, Paul, Rogers and Pelphrey2014; Landa, Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000; Loukusa & Moilanen, Reference Loukusa and Moilanen2009). Pragmatic language impairments can also occur separately from autism and historically, children with pragmatic problems that are not of the pattern or severity as seen in autism, are considered to have a profile that is intermediate between autism and developmental language disorder (previously referred to as “specific language impairment”). In recognition of the potential for pragmatic language difficulties to occur in the absence of either a pervasive developmental or language disorder, a new diagnostic category, social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD) was introduced into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5; see Norbury, Reference Norbury2014, for a practitioner review of SPCD). While the validity of this diagnostic category has been challenged, it represents growing recognition that pragmatic language, and other aspects of language (e.g., Bishop, Reference Bishop2003, Reference Bishop, Verhoeven and Balkom2004, Reference Bishop and Leonard2014), autistic traits (Bishop, Reference Bishop2003; Bölte, Westerwald, Holtmann, Freitag, & Poustka, Reference Bölte, Westerwald, Holtmann, Freitag and Poustka2011), and hyperactivity/inattentiveness (e.g., Greven, Buitelaar, & Salum, Reference Greven, Buitelaar and Salum2018), lie on a continuum. The SPCD category acknowledges that there is a subgroup of children who have pragmatic difficulties that are associated with a significant functional impairment, but to a lesser degree than seen in autism. If we consider pragmatic language problems to be a distinct neurodevelopmental phenomenon, then such difficulties can co-occur with any neurodevelopmental disorder.

The level of overlap between neurodevelopmental disorders broadly, and at a constituent symptom level is very high (see Thapar, Cooper, & Rutter, Reference Thapar, Cooper and Rutter2017). While the core diagnostic features of autism and ADHD are distinct, these two conditions frequently co-occur (Simonoff et al., Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2008; Stevens, Peng, & Barnard-Brak, Reference Stevens, Peng and Barnard-Brak2016). Even in the absence of complete comorbidity, children with one of these conditions often show isolated features of the other. For example, empirical evidence indicates that between 30% and 75% of children with autism diagnoses also have ADHD symptoms (Gadow et al., Reference Gadow, Devincent, Pomeroy and Azizian2005; de Bruin, Ferdinand, Meester, de Nijs, & Verheij, Reference de Bruin, Ferdinand, Meester, de Nijs and Verheij2007; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Biederman, Faraone, Ouellette, Penn and Griffin1996; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Dittner, Bramham, Murphy, Knight and Russell2013; Simonoff et al., Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2008; Sprenger et al., Reference Sprenger, Bühler, Poustka, Bach, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, Kamp-Becker and Bachmann2013), and 20%–60% of those with ADHD have social difficulties that are characteristic of autism (Cooper, Martin, Langley, Hamshere, & Thapar, Reference Cooper, Martin, Langley, Hamshere and Thapar2014; Grzadzinski et al., Reference Grzadzinski, Di Martino, Brady, Mairena, O'Neale, Petkova and Castellanos2011; Grzadzinski, Dick, Lord, & Bishop, Reference Grzadzinski, Dick, Lord and Bishop2016; Leitner, Reference Leitner2014; Nijmeijer et al., Reference Nijmeijer, Hoekstra, Minderaa, Buitelaar, Altink, Buschgens and Hartman2009). Furthermore, children with ADHD are not easily distinguished from those with autism based on the scores obtained from “gold-standard” diagnostic measures of autism (Grzadzinski et al., Reference Grzadzinski, Dick, Lord and Bishop2016). Grzadzinski et al. (Reference Grzadzinski, Dick, Lord and Bishop2016) reported that 21% of their sample of children with ADHD met cut offs for autism on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), and 30% met all autism cut-offs on the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R). Differentiating autism from ADHD in children who are verbally and intellectually able is a particular clinical challenge (Hartley & Sikora, Reference Hartley and Sikora2009; Luteijn et al., Reference Luteijn, Serra, Jackson, Steenhuis, Althaus, Volkmar and Minderaa2000). Therefore, understanding the ways in which the pragmatic language profile of these two conditions differ, and the distinct underlying mechanisms that may drive pragmatic difficulties in these two groups, may be clinically informative in terms of distinguishing autism and ADHD at a behavioral level. Disaggregating the profile of pragmatic difficulties in ADHD may also direct treatment pathways, as current clinical guidelines for ADHD do not describe evidence-based interventions for co-occurring communication problems that may exist among this group.

Both clinical and empirical evidence indicates that “pragmatic language” is an overarching term that encompasses a broad range of distinct skills. We believe the conceptual framework described by Landa (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005), originally in the context of Asperger syndrome and later among typically developing children, may be a valuable framework to help clarify and better understand the nature of pragmatic impairments in children with ADHD. In this framework, Landa (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005) breaks the broader domain of pragmatic language into the subcategories of communicative intent, presupposition, and discourse (social and narrative). Identifying the profile of pragmatic language in ADHD using Landa's framework will also facilitate the comparison of pragmatic profiles across neurodevelopmental disorders.

While the findings from the two previous reviews that have synthesized the extant literature on the nature of pragmatic difficulties in ADHD are valuable in showing that children with ADHD have pragmatic language difficulties, pragmatic language has either been treated as a unitary construct or the studies reviewed have included children without a clinical diagnosis of ADHD. To date, the pragmatic profiles of children with ADHD and those with autism have not been systematically compared. However, the results of a small number of parent-report studies suggest that the level of pragmatic language impairment among children with ADHD may be less severe than that seen in children with autism (Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2010). Thus, important next steps are (a) a systematic review of the empirical literature on the sub-domains of pragmatic language in ADHD, which will enable a description of the profile of pragmatic language in children with ADHD, and (b) comparison of the pragmatic profiles of children with ADHD to those with autism, a neurodevelopmental condition defined by deficits in pragmatic language. In this systematic review, we evaluate and compare the pragmatic language profiles of children diagnosed with ADHD and their TD peers, guided by the theoretical framework proposed by Landa (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005). A secondary goal of this review is to contrast the profile of pragmatic skills in ADHD with those observed in autism, which will allow us to identify similarities and differences in pragmatic language profiles and compare the severity of pragmatic difficulties across the two conditions.

Method

The quality of reporting and conduct of this review is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Protocol and registration

The review is registered with the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews. It is available online at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=82595.

Study selection criteria

Articles were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (a) the article described an empirical study that assessed at least one aspect of pragmatic language in children with ADHD; (b) the findings from the study provided information on the nature, profile, or severity of pragmatic language difficulties rather than just a comparison at the total score level of a measure capturing a range of pragmatic language skills for example, Pragmatic Protocol. In the case of longitudinal or intervention studies baseline data is considered; (c) participants were aged between 5 and 18 years; (d) the study compared groups of children with ADHD to TD children and/or children with autism and reported the performance of these groups separately; (e) children in the ADHD and autism groups had a confirmed clinical diagnosis of ADHD or autism; (f) the study was published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies were excluded if samples were known to include children with IQ scores below 70; and groups included children with comorbid ADHD and autism, unless data from these children were analyzed and reported separately. Studies that reported on groups of children with comorbid autism and ADHD were excluded from this review due to the aim, which was specifically to compare the pragmatic language abilities of these two groups. It was felt that the exclusion criterion regarding comorbid autism and ADHD would minimize the possible confounding influence of the pragmatic language difficulties in autism when compared to ADHD. There was no such exclusion for studies that included children with autism or ADHD and co-occurring language disorders. The inclusion of such studies allows us to parse out the possible effect of structural language difficulties on pragmatic language, particularly in the ADHD sample. In addition, prior to the introduction of the DSM-5, language impairment (i.e., the delay in, or total lack of development of language) was considered core to the diagnosis of autism, so it was impossible to determine which children had autism and comorbid language disorder unless this was reported explicitly.

Search strategy

Articles were identified by searching PsycInfo, PubMed and CSA Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts. PsycInfo and PubMed are considered the two major search engines for clinical psychology literature and use of both is recommended for reviews in this discipline (Wu, Aylward, Roberts, & Evans, Reference Wu, Aylward, Roberts and Evans2012). In addition, we added a specialist linguistics database to ensure coverage of language journals. These three databases were chosen to balance the trade-offs between using a broader selection of databases with lower sensitivity and specificity on this topic with the resource capacity of the researchers (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Aylward, Roberts and Evans2012). A thorough manual reference list search was conducted to identify additional eligible articles. The following filters were applied where permitted: peer-reviewed journals, English language, human research, and children. There were no limitations on year of publication. A wide range of search terms were used to capture studies that covered all the skills comprising pragmatic language as described by Landa (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000). Preliminary searches were conducted to establish the necessary key words to ensure sufficient search breadth. In addition to the constituent skills mentioned within Landa's framework, key terms from the broader pragmatic language literature were used to supplement the terms used. The final key words and MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) included: pragmatic; communication; gesture; presupposition; theory of mind; narrative; discourse; story telling; conversation; social interaction; inference; context; interpret; comprehension; humor; figurative; ADHD. The full search strategy for each database is presented in Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Table S3). Articles were identified with corresponding search terms in the title or abstract. The first author conducted the final search in October 2019; that is, all eligible articles published up to this date were included, there was no lower bound.

Articles identified from the three databases and from manual searching of reference lists (n = 2887) were imported into Endnote X8 and duplicates removed. Article titles and abstracts were screened by SCFootnote 1 to identify studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Short-listed articles were then separately reviewed and selected by SC and HS. A comparison of studies identified for inclusion resulted in kappa = 0.72. Disagreements regarding eligibility were discussed with the last author, who made the final decision about article inclusion.

Data extraction

Data were extracted into a table by SC and each data point was checked for accuracy by HS. Extracted details included the sample demographics (age, gender, IQ, comorbidities), diagnostic procedures, study design (including measures of pragmatic language, study aims, relevant inclusion/exclusion criteria), analyses, and results relevant to the review questions, and covariates. While baseline performance on pragmatic language measures could have been extracted from intervention studies, no such studies were eligible.

Data synthesis

Given the focus of the research question on exploring the profile of pragmatic language skills, a framework was needed to structure the results that would cover the main subcomponents. This was particularly important given the variation in concepts and methods used across studies. Most definitions of pragmatic language are high level and do not offer a breakdown of specific skills (see Table S1) and other reviews have tended to categorize findings by methodology (Adams, Reference Adams2002; Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014). We used the structure provided by Landa's (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005) review of pragmatic language, which has previously been used elsewhere (e.g., Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013). Compared to other definitions, it provides comprehensive coverage of pragmatic skills and when compared alongside other commonly used definitions of pragmatic language, offered a useful structure for our research aims. Thus, study findings were reviewed within the general areas of pragmatic language they addressed: communicative intent, presupposition, social discourse or narrative discourse, or global pragmatic ability. Due to marked heterogeneity in research methods including data coding and analysis, diagnostic procedures, and changes in diagnostic criteria over time, a meta-analysis was not conducted. Summaries of subscale effect sizes for the studies using the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC/CCC-2) are presented in Table 1 (pragmatic subscales) and Supplementary Table S5 (structural language and autism characteristic subscales).

Table 1. A summary of Cohen's d effect size for studies using the Children's Communication Checklist (CCC/CCC-2) for subscales relevant to pragmatic language and pragmatic composite

Note. For the ADHD versus TD comparison, a negative effect represents the ADHD group having more difficulties than the TD group. For the ADHD versus ASD comparison, a negative effect represents the ADHD group having more pragmatic language difficulties than the ASD group. Cohen's d calculations used pooled standard deviation which incorporated sample size where it differed across the groups.

a Sum of subscale scores for inappropriate initiations, coherence, stereotyped conversation, use of conversational context, and conversational rapports

b Sum of subscale scores for coherence, inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, and nonverbal communication

c Sum of subscale scores for coherence, inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context

d Derived by taking the mean for six subscales: inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, nonverbal communication, social relations, interests. Social relations and interests are reported in Supplementary Table S5.

e Sum of subscale scores for inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, and nonverbal communication

ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CCC/CCC-2 = Children's Communication Checklist; TD = typically developing

Quality and strength of evidence assessment

The full list of criteria for the quality and strength of evidence assessment are presented in Supplementary materials. These criteria were adapted from the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins, & Micucci, Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci2004) and Cochrane Risk of Bias Criteria (Higgins & Altman, Reference Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green2008). For the current review, the criteria included: representativeness of the cases and controls; size of the sample; reliability and validity of the measure(s) of pragmatic language; and assessment and management of missing data.

Results

Study selection

The electronic database search yielded 2,879 articles, with a further eight identified through reference list searches. A full article review was conducted for 137 articles; 104 were excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (the full list of excluded articles is presented in Supplementary Table S4). A total of 33 articles reporting on 34 studies were included (see PRISMA flow chart displayed in Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart of study selection.

Study characteristics

Of the 34 studies included in this review, 33 compared an ADHD group with a TD comparison group and eight an ADHD group with an autism sample (seven of these included a TD control group, one did not). There were 1,407 participants with ADHD (1,069 boys and 338 girls, ratio 3.2:1, mean age = 9.5 years), 1058 TD participants (805 boys, 251 girls, ratio 3.2:1, 2 unknown, mean age = 9.6 years), and 380 participants with autism (347 boys, 33 girls, ratio 10.5:1, mean age = 10.0 years). One study was a longitudinal design, all others were cross-sectional. Studies covered a range of methodologies for the assessment of pragmatic language, including parent- (n = 8), or teacher- (n = 3) report, direct/standardized assessment (n = 7), social interaction tasks (n = 9), study unique methodology (n = 2), and narrative production/retelling tasks (n = 12). Three of the studies used more than one of these methodologies (Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017; Ohan & Johnston, Reference Ohan and Johnston2007; Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013).

Summary of findings

We present the findings below using Landa's (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005) framework. Full details of the results of each study are presented in Table 2. Studies are grouped according to the subdomain of pragmatic language they measured. We did not identify any studies that measured communicative intent. Where only a few studies were identified for a pragmatic subdomain, results are discussed study by study; where the number of studies permitted (predominantly in the area of narrative discourse), results are grouped by pragmatic skill, though where this was possible the number of studies in each subdomain is still relatively small.

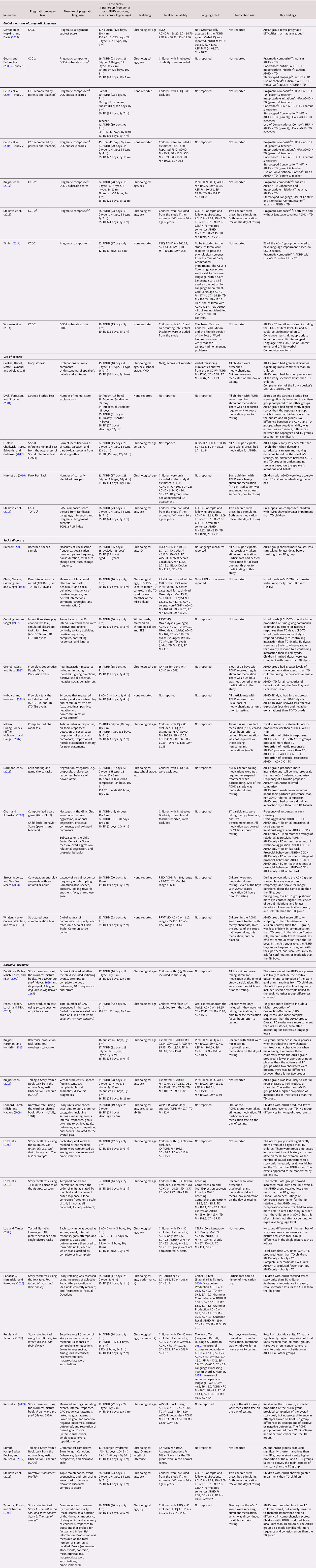

Table 2. Systematic review study characteristics and key findings

Note. Studies are listed first by the subcategory of pragmatic language measured, and secondly by alphabetical order. Relevant findings from Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) and Kuijper et al. (Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017) are reported in more than one section. ADHD – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADOS – Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; AS – Asperger syndrome; BPVS – British Picture Vocabulary Scale; CASL – Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; CCC/CCC-2 – Children's Communication Checklist; C-type (ADHD-C) – ADHD combined-type; FSIQ – Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; GAO – Goal-Attempt-Outcome units; GAO Sequences – sequences that include an initiating event to set up the character's overall goal, actions that explicitly or implicitly connect to the goal (attempts), and outcomes that are the result of the protagonist's action in relation to the goal. HFA – high-functioning autism; H-type – ADHD hyperactive-type; I-type (ADHD-I) – ADHD inattentive-type; LI – language impairment; NVIQ – Nonverbal Intelligence Quotient; ODD – oppositional defiant disorder; OWLS – Oral and Written Language Scales; PLU – Pragmatic Language Usage; PPVT-III-NL Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 3rd Edition, Dutch translation; SIDC – Social Interaction Deviance Composite; SES – socioeconomic status; TD – typically developing; TOPL-2 – Test of Pragmatic Language, second edition; WBQ – Word Comprehension Quotient; VCI – Verbal Comprehension Index; WISC-III – Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, third edition; WISC-IV – Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children 4th Edition

a CASL/TOPL scales: higher score indicates greater pragmatic language skill

b As the meaning of a higher score differs across versions of the CCC and individual studies, we have reported findings in terms of more/less impairment where “>” means “more impairment than” and “<” means “less impairment than”. These symbols are only used where the difference is significant.

c Sum of subscale scores for coherence, inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, and nonverbal communication

d Sum of subscale scores for inappropriate initiations, coherence, stereotyped conversation, use of conversational context, and conversational rapports

e The correlation between the two pragmatic language measures used in Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017 (CCC-2 and narrative discourse) was −0.21 and was significant at p < .01.

f Sum of subscale scores for inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, and nonverbal communication

g Correlations between the three pragmatic language measures used in Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013 (CCC-2, presupposition composite and Narrative Assessment Profile) ranged between 0.29 and 0.40. All three correlations were significant at p < .05.

h Sum of subscale scores for coherence, inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context

j The Social Interaction Deviance Composite (SIDC) identifies children who have pragmatic difficulties that are disproportionate to their structural language skills.

i Derived by taking the mean for the six CCC-2 pragmatic language subscales: inappropriate initiations, stereotyped language, use of context, nonverbal communication, social relations, interests

k The authors created a series of 16 stories, each of which described an everyday situation and ended with an ironic statement. Each ironic story was matched to a corresponding story in which the final sentence was modified to become a literal statement. Every story was followed by three kinds of questions: one requiring an explanation of the ironic statement; and two assessing the child's understanding of the speaker's beliefs.

l Correlations between the pragmatic language measures used in Ohan & Johnston, Reference Ohan and Johnston2007 (computer task, parent report and teacher report) ranged between 0.10 to 0.41. Not all were significant at p < .05.

Global pragmatic language skills

We identified eight studies that used standardized language measures (Demopoulos et al., Reference Demopoulos, Hopkins and Davis2013) or parent/teacher-report questionnaires (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017; Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013; Timler, Reference Timler2014; Vaisanen et al., Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014) to compare the pragmatic language skills of children with ADHD to TD children (n = 7) or children with autism (n = 5). The results of the seven studies that used either the CCC or the CCC-2 showed that both the subscale and pragmatic language composite scores for children with ADHD indicated less well developed pragmatic skills than their TD counterparts (see Table 1 for a summary of effect sizes) (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017; Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013; Timler, Reference Timler2014; Vaisanen et al., Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014) (see Table 2). At a subscale level, children with ADHD have greater pragmatic difficulties than TD children on the CCC/CCC-2 coherence (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008), inappropriate initiation (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017), use of context (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017), nonverbal communication (Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017), and conversation (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004) subscales. Vaisanen et al. (Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014) showed that children with ADHD had greater pragmatic difficulty than their TD peers for all CCC-2 subscales.

The pragmatic language difficulties of children with ADHD have been shown to persist after controlling for comorbid language impairment (LI). For example, Timler (Reference Timler2014) assessed the impact of comorbid language impairment (defined as a score ≤85 on the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, Fourth Edition [CELF-4] or the Test of Narrative Language [TNL]) on CCC-2 scores for children with ADHD. The children with ADHD + LI had significantly lower pragmatic composite scores than those without LI, who in turn had lower pragmatic scores than the TD group. Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) similarly found that, after controlling for general language ability (measured using the CELF-4), children with ADHD had significantly lower CCC-2 pragmatic composite scores than TD children. These findings suggest that pragmatic difficulties in ADHD may be disproportionate to their general language abilities. Results reported by Vaisanen et al. (Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014) showed that, relative to the TD group, a significantly higher proportion (58%) of the ADHD group obtained SIDC (Social Interaction Deviance Composite, also referred to as the SIDI, Social Interaction Difficulties Index) scores that indicated pragmatic language impairments (i.e., a mismatch between pragmatic and structural language skills, see Ash, Redmond, Timler, & Kean, Reference Ash, Redmond, Timler and Kean2017 for a discussion of this composite score).

Several studies have compared pragmatic language skills in children with ADHD and those with autism (Geurts et al., Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2008; Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017). Together, the results show that, relative to children with autism, those with ADHD have fewer parent- and teacher-reported pragmatic difficulties at the level of pragmatic composite scores. Children with ADHD also have significantly higher scores (i.e., fewer pragmatic difficulties) than children with autism on direct assessments of their ability to make flexible and pragmatically accurate social judgements (Demopoulos et al., Reference Demopoulos, Hopkins and Davis2013).

While differences between ADHD and autism groups are evident on specific CCC subscales, findings have been mixed. For example, Geurts et al. (Reference Geurts, Verté, Oosterlaan, Roeyers, Hartman, Mulder and Sergeant2004) found that children with ADHD had lower levels of parent-reported difficulties than children with autism on the coherence, stereotyped language, and use of context subscales. In contrast, Kuijper et al. (Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017) reported that their autism and ADHD groups were indistinguishable on the coherence subscale. The results of this latter study also showed that the ADHD group had fewer parent-rated impairments than the autism group on the use of context and nonverbal communication subscales of the CCC-2. Results consistently show that autism and ADHD groups have similar scores on the inappropriate initiation subscale, with both clinical groups obtaining lower scores (i.e., more impairment) than TD controls (see Table 2).

Evidence from parent- and teacher-report, as well as direct language assessments, suggests that children with ADHD have pragmatic language skills that fall between those of children with autism and their TD peers. Children with ADHD appear to have particular difficulties with making appropriate social initiations, as there are clear distinctions between these children and their TD counterparts in the frequency with which they make inappropriate initiations (e.g., Vaisanen et al., Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014). Accounting for general language skills does not explain the group differences between children with ADHD and TD controls. The results of these studies suggest that pragmatic difficulties in ADHD are frequently accompanied by structural language weaknesses, but the pragmatic difficulties are greater than expected given structural language competencies.

Presupposition

Presupposition can be measured by testing a child's comprehension of nonliteral language (e.g., irony, sarcasm, metaphor) and their ability to use and interpret aspects of the social context to inform their judgements and inferences (Landa, Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000). Altogether five studies were identified that examine presupposition in ADHD (see Table 2).

Using tasks that required children to identify nonliteral language, two studies show that children with ADHD are less able to explain ironic comments (Caillies et al., Reference Caillies, Bertot, Motte, Raynaud and Abely2014) and identify social “faux pas” (Mary et al., Reference Mary, Slama, Mousty, Massat, Capiau, Drabs and Peigneux2016) than their TD peers.

Difficulties with presupposition in children with ADHD have also been identified on standardized language assessments. Using The Awareness of Social Inference Test, Ludlow and colleagues (Ludlow et al., Reference Ludlow, Chadwick, Morey, Edwards and Gutierrez2017) found that while children with ADHD did not differ from TD children in their ability to detect sincerity or simple sarcasm (where it is clear that the speaker means something different to the literal statement), those with ADHD were significantly less accurate when detecting paradoxical sarcasm (where the script makes no literal sense unless it is assumed that one speaker is being sarcastic) than the TD children. Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) derived a composite measure of presupposition from subtest scores on the CASL (nonliteral language, inferences, pragmatic judgement) and the Test of Pragmatic Language (TOPL-2). After controlling for general language ability (scores on the CELF-4), children with ADHD obtained significantly lower presupposition scores than TD children.

We identified only one study that compared presupposition in children with ADHD, autism, and TD controls (Dyck et al., Reference Dyck, Ferguson and Shochet2001). In this study, there were no differences in the scores of the ADHD and TD groups. After controlling for IQ, the children with ADHD provided a significantly higher number of accurate mental state explanations than those with autism. These preliminary findings suggest that the presuppositional skills of children with ADHD are stronger than those of children with autism.

The studies described in this section show that overall, the presupposition skills of children with ADHD; that is, their ability to detect sarcasm, irony, and social faux pas, are less well developed than those of their TD peers. The one exception was the study by Dyck et al. (Reference Dyck, Ferguson and Shochet2001), with results showing that children with ADHD had similar scores to TD children on the Strange Stories Test. Scores for the TD and ADHD groups were both at ceiling on this measure, so it is possible that the Strange Stories Test is not sensitive enough to detect presupposition difficulties in children with ADHD.

Social discourse

Ten studies were identified that addressed social discourse skills; nine through a social interaction task and one via a recorded speech sample (see Table 2).

Results from computer simulated interaction tasks, and parent and teacher ratings are consistent in showing that the messages of girls with ADHD were less prosocial, more awkward, and more overtlyFootnote 2 and relationally aggressive during interaction with peers than TD children (Ohan & Johnston, Reference Ohan and Johnston2007). These findings may, in part, reflect difficulties interpreting what is acceptable or expected in particular social contexts, but also appear to be driven to some extent by the presence of comorbid oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) in children with ADHD. However, the ODD diagnoses were not independent of ADHD subtype, which may confound the results. Using a computerized chatroom task, Mikami and colleagues (Mikami et al., Reference Mikami, Huang-Pollock, Pfiffner, McBurnett and Hangai2007) found that children with combined (ADHD-C) or inattentive (ADHD-I) type ADHD made significantly more off-topic responses than TD controls. While children with ADHD-C made more hostile responses than both the ADHD-I group and TD controls, there were no differences in the frequency of prosocial responses across the three groups.

Social discourse has also been examined using dyadic interaction tasks. These tasks have involved examining interactions between mixed dyads (i.e., those with one TD and one ADHD child), and dyads that contain two TD children. Within these tasks, outcome measures have included communicative acts, such as noncommunicative speech, reciprocity, assertiveness, and friendliness. Results obtained from studies that include dyads of unfamiliar peers show that, while there are no differences in communicative behavior between boys with ADHD and TD boys when first meeting and interacting with a peer (Grenell et al., Reference Grenell, Glass and Katz1987), differences emerge over the course of their interactions. Boys with ADHD engage in more noncommunicative speech than TD boys during cooperative tasks and are rated as being less friendly but more assertive during conflict resolution tasks (Grenell et al., Reference Grenell, Glass and Katz1987). Relative to TD boys, those with ADHD are also less likely to request guidance or information, and more likely to disagree with their peers (Whalen et al., Reference Whalen, Henker, Collins, McAuliffe and Vaux1979). Within mixed dyads, significantly less verbal reciprocity (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Cheyne, Cunningham and Siegel1988; Hubbard & Newcomb, Reference Hubbard and Newcomb1991) and affective expression (Hubbard & Newcomb, Reference Hubbard and Newcomb1991) has been observed, when compared to TD dyads. Mixed dyads are also characterized by a higher frequency of questions and a more controlling communication style than dyads containing two TD (Cunningham & Siegel, Reference Cunningham and Siegel1987).

Similar results are reported during dyadic interaction tasks that include either a friend or an unfamiliar adult (Normand et al., Reference Normand, Schneider, Lee, Maisonneuve, Kuehn and Robaey2011; Stroes et al., Reference Stroes, Alberts and Van Der Meere2003). When interacting with a friend during card sharing and game choice tasks, Normand et al. (Reference Normand, Schneider, Lee, Maisonneuve, Kuehn and Robaey2011) rated children with ADHD as making significantly more insensitive and self-centered proposals (though a similar number of altruistic proposals), fewer inquiries as to their partner's thoughts, and as having a more dominant interaction style, relative to comparison children. During structured interactions with unfamiliar adults, children with ADHD talked more, particularly about the same subject, made more verbal initiations and generated more self-talk than TD children (Stroes et al., Reference Stroes, Alberts and Van Der Meere2003).

Social discourse has also been examined using speech samples recorded from interviews between children and a researcher. Breznitz (Reference Breznitz2003) found that boys with ADHD were more likely to pause, take fewer turns and have longer delays prior to speaking than their TD peers. These behaviors may indicate social discourse incoherence in the ADHD sample (Breznitz, Reference Breznitz2003), though alternative explanations for such behaviors among individuals with ADHD have also been made (e.g., Bangert & Finestack, Reference Bangert and Finestack2020).

Together, these 10 studies suggest that children with ADHD have a more dominant and hostile style of social discourse than TD children. However, given the broad range and study specific nature of the tasks used to facilitate social discourse, together with differences in the coding systems used to assess this pragmatic skill, it is difficult to compare the results across studies. While some findings indicate that the style of social discourse may differ depending on the ADHD subtype (e.g., combined vs. inattentive), or in the presence of co-occurring oppositional behaviors, it is premature to draw conclusions about the nature of these differences when so few studies have compared performance between these ADHD subgroups. In addition, no studies were identified that compared the social discourse of children with ADHD with those of children with autism, thus limiting the conclusions we can make about whether the profile of social discourse skills in ADHD resembles the profile seen in autism.

Narrative discourse

Fourteen studies measured narrative coherence and cohesiveness, aspects of pragmatic language essential to narrative discourse, in children with ADHD, TD children, or those with autism. While studies have typically used narrative production tasks, such as story retelling, to measure these aspects of communication, the specific measure of coherence has varied (see Table 2). Measures of narrative coherence included: (a) the frequency of goal-based units; (b) quality of goal-based units; (c) presence of a story resolution; (d) maintenance of a story-line; (e) story structure; (f) presence of transitions (e.g., words such as and, then, because); (g) use of pronouns when referring to characters; (h) overall number of errors (e.g., in introducing extraneous information, incorrect word substitution, and incorrect/misinterpreted information); and (i) fluency.

Overall, the results of these studies indicate that children with ADHD provide fewer story units of significant thematic importance than TD children (Lorch et al., Reference Lorch, Milich, Flake, Ohlendorf and Little2010; Papaeliou et al., Reference Papaeliou, Maniadaki and Kakouros2015; Rumpf et al., Reference Rumpf, Kamp-Becker, Becker and Kauschke2012). Findings regarding the frequency with which children with ADHD include goal-based units have been mixed. When children with ADHD do provide goal-based units, these are less frequent and of lower quality (e.g., missing key details) than the goal-based units produced by TD children (Derefinko et al., Reference Derefinko, Bailey, Milich, Lorch and Riley2009; Freer et al., Reference Freer, Hayden, Lorch and Milich2011; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Lorch, Milich and Hagans2009; Renz et al., Reference Renz, Lorch, Milich, Lemberger, Bodner and Welsh2003). In contrast, Freer et al. (Reference Freer, Hayden, Lorch and Milich2011) reported that, while there are a similar number of goal-based events in the stories of children with ADHD and TD children, those with ADHD produce more stories with no goal-based units than their TD peers. Results of a study by Derefinko et al. (Reference Derefinko, Bailey, Milich, Lorch and Riley2009) indicate that, relative to the TD children, those with ADHD were less likely to include the story resolution in their narratives. These types of omissions can result in unclear communication and may be confusing for the listener.

The lack of goal-based units is not the only identified area of weakness in the narratives of children with ADHD. For children with ADHD, stories containing at least one goal-based event were rated as less coherent than those of the TD children, marked by poorly maintained storylines, list-like structures, and fewer instances of transitions (Freer et al., Reference Freer, Hayden, Lorch and Milich2011). Coherence also requires the speaker to be specific about to whom or what they are referring. The results of three studies indicate that, relative to TD children, those with ADHD are more likely to use ambiguous pronouns, that is, pronouns that are not linked to a specific character or object (Lorch et al., Reference Lorch, Diener, Sanchez, Milich, Welsh and Broek1999; Purvis & Tannock, Reference Purvis and Tannock1997), and make reference errors, or errors that result in ambiguity (Renz et al., Reference Renz, Lorch, Milich, Lemberger, Bodner and Welsh2003).

Narrative cohesion and coherence are also affected by the number of errors that the narrator makes. Evidence from several studies indicates that children with ADHD produce stories that are characterized by more errors than those of TD controls. The types of errors observed in these stories include making embellishments (i.e., introducing extraneous information) (Lorch et al., Reference Lorch, Diener, Sanchez, Milich, Welsh and Broek1999), ambiguous references (Lorch et al., Reference Lorch, Diener, Sanchez, Milich, Welsh and Broek1999; Purvis & Tannock, Reference Purvis and Tannock1997; Tannock et al., Reference Tannock, Purvis and Schachar1993), inappropriate word substitutions, and incorrect or misinterpreted information (Purvis & Tannock, Reference Purvis and Tannock1997; Tannock et al., Reference Tannock, Purvis and Schachar1993).

It is possible that expressive language skills account for differences in narrative coherence between ADHD and TD groups. The results of some studies indicate that group differences in narrative discourse disappear after controlling for expressive language levels (Freer et al., Reference Freer, Hayden, Lorch and Milich2011; Lorch et al., Reference Lorch, Milich, Flake, Ohlendorf and Little2010). Luo and Timler (Reference Luo and Timler2008) also found that it was only children with ADHD and a co-occurring language impairment (defined as a composite standard score of ≤85 on the CELF-4 and a history of receiving speech/language services), who included fewer goal-based units in their narratives than the TD children. In contrast, Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) found that, after controlling for general language ability (CELF-4 scores), children with ADHD still had lower narrative discourse scores than TD children. Thus, findings regarding the role of general language abilities in narrative discourse in ADHD are mixed.

Only two studies have examined narrative coherence in children with ADHD, those with autism and TD children. Rumpf et al. (Reference Rumpf, Kamp-Becker, Becker and Kauschke2012) found that, while TD children were more able to convey the key aspects of a story than children with ADHD and those with Asperger syndrome, these latter two groups were indistinguishable. Results reported by Kuijper et al. (Reference Kuijper, Hartman, Bogaerds-Hazenberg and Hendriks2017) also suggest that children with autism and those with ADHD are less fluent in their narrations, as they interrupted their stories more often than the TD children. While children with ADHD and those with autism take listeners into account with their choice of referent and use the same referent when introducing or re-introducing characters, those with ADHD made more errors of ambiguity than were recorded for the autism group (Kuijper et al., Reference Kuijper, Hartman and Hendriks2015). This manifested in less specific references to characters.

Thus, across studies looking at narrative coherence, the narratives from children with ADHD were rated as being less coherent than their TD peers, as their stories included fewer goal-based or thematically significant events, a feature that may be similar to the narratives of children with autism. Other indicators of coherence, such as the number of errors and ambiguous references, also distinguished the narratives of children with ADHD from those of TD children. These aspects of narrative coherence may differentiate the narratives of ADHD and autism samples. However, not all indicators of coherence show differences between children with and without ADHD. For example, the provision of contextual information, such as the timing and setting of events, as well as the characters involved and their mental states, have been shown to be similar across ADHD and TD groups (Luo & Timler, Reference Luo and Timler2008; Renz et al., Reference Renz, Lorch, Milich, Lemberger, Bodner and Welsh2003; Rumpf et al., Reference Rumpf, Kamp-Becker, Becker and Kauschke2012). In addition, findings regarding the impact of language levels on narrative coherence were mixed, thus we are unable to establish, based on the extant literature, whether the differences between the ADHD and TD groups on measures of narrative coherence are accounted for by poor language skills.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Quality and risk of bias ratings varied across studies. Criteria used are reported in Supplementary materials. Out of 238 individual ratings (34 studies across seven categories), 37% (n = 87) were good or low risk of bias, 33% (n = 79) as satisfactory or moderate risk of bias, and 15% (n = 35) were rated as poor or high risk of bias. Fourteen percent (n = 34) could not be rated as the relevant information was not reported and 1% of ratings were not completed as they were not applicable (n = 3). Nine studies (26%) had no “poor” or “high risk” ratings. Twenty-five studies (74%) had at least one “poor” or “high risk” rating, of which eight (24%) had two or more. Small sample sizes and non-representative cases were the most common limitations. Table 3 indicates the relative gradings across studies for the categories of bias. A review of the table in relation to study effect sizes does not indicate any obvious relationship between study quality and study outcome.

Table 3. Risk of bias and quality assessment across studies

Note.

Ratings are: good/low risk of bias (light gray), satisfactory/moderate risk of bias (mid gray) or poor/high risk of bias (dark gray). NA = not available; NR = not reported. Validity information was considered not available for two studies where the measurement tool considered in this review to measure pragmatic language was used with the intention to measure theory of mind. The full list of criteria for the quality and strength of evidence assessment are presented in Supplementary Materials. These criteria were adapted from the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci2004) and Cochrane Risk of Bias Criteria (Higgins & Altman, Reference Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green2008).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the empirical literature that examines pragmatic language in children diagnosed with ADHD. Specifically, we review studies comparing the pragmatic language skills of children with ADHD to those of TD children, which incorporate a range of methodologies. By doing so, the review complements and extends the work of previous reviews of pragmatic language in ADHD (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017). It also explores the specificity of the profile of pragmatic language in ADHD through the inclusion of studies that directly compared pragmatic language in children with ADHD to pragmatic language in children with autism. In order to consider the full range of skills encompassed by “pragmatic language”, Landa's (Reference Landa, Klin, Volkmar and Sparrow2000, Reference Landa2005) conceptual framework of pragmatic language (communicative intent, presupposition, and discourse) is used to examine the various elements of pragmatic competence.

Summary of key findings

In line with previous research, our review shows that studies using global measures of pragmatic language consistently reveal difficulties in children with ADHD, compared to their TD peers (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017). When looking at specific subcomponents of pragmatic language, relative to TD children, those with ADHD were found to have difficulties within the domains of presupposition, social discourse, and narrative discourse. Among the small number of studies that compared pragmatic language in ADHD to that in autism, the global pragmatic skills of children with ADHD were consistently reported to be intermediate between the TD children and those with autism, suggesting a difference in the severity of their respective pragmatic language difficulties. However, the modest number of comparative studies limits any conclusions that can be drawn about the similarities and differences in the pragmatic language profiles of the two clinical groups.

Pragmatic language in ADHD

While studies that provide summary pragmatic language scores have been valuable in drawing attention to pragmatic language impairments in ADHD, breaking pragmatic language into subcomponents provides a better indication of specific areas of difficulty in this population. No studies were identified that assessed the communicative intent of children with ADHD (for suggested methodologies see Adams, Reference Adams2002). However, there was clear evidence that children with ADHD make more inappropriate initiations than their TD peers. In addition, the social interactions of children with ADHD are consistently described as being more hostile and controlling than TD children. The pragmatic language profile in ADHD has also been shown to be characterized by difficulties understanding nonliteral language, for example, irony/sarcasm and less social reciprocity than would be expected for the children's age. In terms of narrative discourse, children with ADHD are less likely than their TD peers to include goal-based elements in narratives and make more errors of ambiguity when telling stories, thus their narratives are less coherent than those of other children.

The results of this review suggest that children with ADHD have a language profile characterized by pragmatic language difficulties that are disproportionate to their general language skills (e.g., Vaisanen et al., Reference Vaisanen, Loukusa, Moilanen and Yliherva2014). Evidence supporting this claim comes from studies of global pragmatic language in ADHD, showing that these difficulties persist after controlling for structural language skills (e.g., Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013). Few of the studies that investigated the subcategories of pragmatic language in ADHD controlled for co-occurring language impairments, so it is difficult to determine whether specific areas of pragmatic difficulty in ADHD are secondary to structural language impairments. In addition, the results of the studies that did account for general language skills were mixed. For example, findings reported by Staikova et al. (Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013) suggest that difficulties with narrative coherence in ADHD are unrelated to language levels. In contrast, expressive language appears to contribute to group differences in narrative discourse (Freer et al., Reference Freer, Hayden, Lorch and Milich2011; Lorcht et al., Reference Lorch, Milich, Flake, Ohlendorf and Little2010). Without accounting for general language levels, which are more likely to be impaired in this population (Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017), we cannot establish whether global pragmatic language difficulties, or difficulties with subcomponents of pragmatic language, reflect an overall picture of poor language skills in children with ADHD, or alternatively, represent a specific area of difficulty that is misaligned with general language skills in these children.

Specificity of the pragmatic language profiles of ADHD and autism

Our results build on the findings of a previous review to highlight that children with ADHD and children with autism share a global deficit in pragmatic language (Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2010). The current findings indicate that the level of impairment in ADHD is less pronounced than seen in children with autism, as most clearly evidenced on the CCC/CCC-2. Fine-grained analyses of the CCC/CCC-2 subscale scores also show that both clinical groups have difficulties with inappropriate initiation, although it is not clear from the literature that these reflect the same underlying processes. The reviewed literature also indicates that children with autism are relatively more impaired than children with ADHD in their use of context and nonverbal communication. However, there appear to be shared difficulties in some aspects of narrative discourse, narrative length, and overall coherence. Overall, the evidence reviewed does not elucidate a specific profile of pragmatic language in ADHD, which can be distinguished from the profile that characterizes autism.

Importantly, we only identified seven studies that directly compared pragmatic language in autism and ADHD. Therefore, while we can identify shared difficulties in the pragmatic profiles of these two conditions, it is difficult to compare the degree of impairment in each discrete component. We can be more confident that there is a difference in the degree of global pragmatic language difficulties in autism and ADHD, as a number of studies have now compared CCC/CCC-2 scores for these two groups. Further studies comparing the two clinical groups are needed to clarify the degree of impairment across the pragmatic profile of these two clinical conditions.

In reviewing the extant literature, another important consideration is the range of dates, which spanned the period in which the DSM changed from the fourth to the fifth edition. In the DSM-IV (Criterion E), ADHD could not be diagnosed if the inattentive/hyperactive symptoms occurred in the presence of a pervasive developmental disorder, such as autism (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The same criterion did not apply to diagnoses of autism, which did not preclude ADHD as a co-occurring condition. Therefore, for studies that predated the DSM-5, while we can be sure that the ADHD samples did not include children with formal diagnoses of autism, the children with autism may have had comorbid ADHD. This has a confounding influence on our findings, as the presence of ADHD in children with autism may inflate the pragmatic language difficulties observed in these samples. This could occur most obviously through symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity interfering with both the performance and opportunity to practice pragmatics. In addition, for children with both comorbid ADHD and autism, this could obscure any distinctions in the pragmatic language profiles of these two groups.

Strengths and limitations

We present a rigorous systematic review of the literature examining pragmatic language in ADHD. This review extends and complements previous reviews (Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017). Organizing the review around Landa's framework facilitated the breakdown of the broad concept of pragmatic language into constituent skills, which allows for the inclusion of a wider range of studies than in the previous reviews (see Supplementary Table S6, which shows the additional studies included in the current review, as compared to the reviews conducted by Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Korrel et al., Reference Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson and Sciberras2017); identification of specific areas of pragmatic difficulty for children with ADHD; and highlighting of important gaps in the existing research literature. We also augment previous work by only reviewing studies that included samples of children who had received a clinical diagnosis of ADHD.

Our review is limited by the quality and quantity of the available literature. Across studies, there is a high degree of heterogeneity in the measures used to assess pragmatic language. While some studies have used parent- or teacher- report pragmatic measures, others have used standardized language assessments, and still others developed study-specific tasks. Even when studies have utilized similar measures, the construction of pragmatic language composite scores has varied. For example, among the studies that implemented the CCC-2, each uses different subscales to derive a pragmatic language composite score. Several studies employed study-specific pragmatic language measures, often without establishing the psychometric properties of these tasks. There has been a call for more rigorous investigation of the validity of pragmatic language assessments (Adams, Reference Adams2002; Geurts & Embrechts, Reference Geurts and Embrechts2010). We rated 47% of the reviewed studies’ measures of pragmatic language as having face validity only. In addition, across the studies that used comparable narrative or social interaction tasks, the researchers designed unique and varied coding systems, which prevented us from combining the findings across groups of studies. Therefore, undertaking a formal meta-analysis was not appropriate given the range of methodologies, presentation of the data, and variable aspects of pragmatic language assessed. Consistency of pragmatic measures across future studies will be important in guarding against publication bias and its inflation on risk estimates as this area of research moves toward clinical implementation. In selecting appropriate measures, researchers should consider that standardized measures of overall pragmatic language skills or broader skill sets such as narrative ability may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect some of the subtle difficulties in children with ADHD (e.g., Redmond, Thompson, & Goldstein, Reference Redmond, Thompson and Goldstein2011).

There are a range of factors that limit the generalizability of our findings. Most of the samples were small and mainly included boys. While this is likely to represent clinical samples, it is unclear how well the findings generalize to girls with ADHD. Furthermore, very few studies controlled for the effects of sex, age, language ability, or cognitive functioning on pragmatic language, making it difficult to disentangle the way in which these developmental factors influence pragmatic language in samples of children with ADHD. Given the preliminary findings that structural language may influence pragmatic language, consideration of wider language skills will be pertinent in future research.

Furthermore, although we took many steps to avoid bias throughout the review, there may be a risk of publication bias. The current review included peer-reviewed studies only, that is, no gray (unpublished) literature, to increase the overall quality of the included studies. This practice may have excluded some studies reporting nonsignificant findings. As the data did not support conducting a meta-analysis, no formal publication bias analyses were conducted. In sum, these aspects may limit confidence in the conclusions that can be drawn from this synthesis of the literature.

Clinical implications

The findings of the current review have important implications for the assessment and management of children with ADHD. The data indicate that, as a group, children with ADHD have difficulties with pragmatic language. When presenting problems include symptoms of ADHD, clinicians should consider screening for co-occurring pragmatic and structural language difficulties. In the case of a positive screen, consideration should be given to the need for a comprehensive language evaluation. Since anecdotal clinical reports indicate that there is a mismatch between some children's pragmatic knowledge and the application of that knowledge to real-life settings, where possible, clinical evaluations should include “live” evaluations of pragmatic language skills. From the perspective of intervention, knowledge of any deficits in the language skills of a child with ADHD will help guide the selection and implementation of skills training and educational support/accommodations. Current recommended treatments for ADHD (e.g., pharmacotherapy and behavioral parent training) do not address pragmatic language or structural language impairments. Highlighting the existence and nature of these difficulties will, we hope, increase children's access to speech and language services; encourage research, and facilitate the development of interventions that include tools for pragmatic language skill development in addition to addressing any structural language weaknesses. Such interventions should focus on addressing oral language skills and ways to use these skills in socially meaningful ways.

Future research

The results of this review trigger a call to further research in this area. Firstly, given the consistent findings of pragmatic language difficulties in ADHD, more attention is needed on the functional impact associated with such difficulties (e.g., for social, academic, or mental health outcomes). Given preliminary evidence that pragmatic language mediates the relationship between ADHD and social difficulties, this is an important area of future research (Staikova et al., Reference Staikova, Gomes, Tartter, McCabe and Halperin2013).

Secondly, while the research reviewed here helps to clarify the profile of pragmatic language impairments in ADHD, it does not address their etiology. While several hypotheses about the underlying mechanisms of pragmatic language impairments in ADHD have been purported, the extent to which pragmatic language is explained by the core symptoms of ADHD, executive function difficulties or other causes is unknown (Camarata & Gibson, Reference Camarata and Gibson1999; Green et al., Reference Green, Johnson and Bretherton2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Gathercole, Astle, Holmes and Team2016). When comparing the pragmatic skills in ADHD and autism, it is possible that the shared difficulties are driven by distinct mechanisms. For instance, in ADHD inappropriate initiation could relate to the core symptom of impulsivity, that is, talking too much, interrupting, and intruding, whereas in autism, scores representing greater levels of difficulty could arise because of restricted interests and rigidity that is, talking repeatedly about the same topic. Research that disentangles the relative contribution of cognitive (e.g., executive function) or behavioral (e.g., impulsivity) factors to pragmatic language problems in ADHD and other neurodevelopmental disorders will help to clarify the etiology of these difficulties. A greater understanding of pragmatic language in different ADHD subtypes, and studies of the impact of commonly co-occurring conditions (e.g., autism or ODD) and structural language skills on pragmatic language in ADHD, will also help to elucidate underlying mechanisms. One area of interest would be to consider the effect of pharmacological interventions that target core ADHD symptoms on pragmatic language. While some preliminary studies have tested the impact of stimulant medication on pragmatic narrative abilities, mixed results and small samples limit any conclusions that can be drawn (Bailey, Derefinko, Milich, Lorch, & Metze, Reference Bailey, Derefinko, Milich, Lorch and Metze2011; Derefinko et al., Reference Derefinko, Bailey, Milich, Lorch and Riley2009; Rausch et al., Reference Rausch, Kendall, Kover, Louw, Zsilavecz and Van der Merwe2017). In turn, such knowledge can support the design of interventions targeting pragmatic language. Some preliminary work has been conducted on developing pragmatic language interventions for children with ADHD; however, the studies are small and the findings are mixed (Cordier et al., Reference Cordier, Munro, Wilkes-Gillan, Ling, Docking and Pearce2017; Cordier, Munro, Wilkes-Gillan, & Docking, Reference Cordier, Munro, Wilkes-Gillan and Docking2013; Wilkes-Gillan, Cantrill, Parsons, Smith, & Cordier, Reference Wilkes-Gillan, Cantrill, Parsons, Smith and Cordier2017).

Within the context of the current review, it is important to consider how the changes to the diagnostic criteria for neurodevelopmental disorders introduced in the DSM-5 may influence future research on, or the interpretation of, pragmatic language difficulties in children diagnosed with ADHD. This is especially relevant when children with ADHD are compared to those with clinical diagnoses of autism or S(P)CD, and when considering comorbid communication disorders in the setting of ADHD. Most of the studies included in the current review predate the introduction of S(P)CD, and those that were published after the implementation of the DSM-5 do not address this new diagnostic category. Therefore, we do not know whether any of the children in these studies would meet contemporary diagnostic criteria for S(P)CD and if this would change our findings. It is possible that some children diagnosed with autism might be better described as having S(P)CD, but only if there was no evidence of rigid and repetitive behaviors and restricted interests, a pattern which appears to be relatively uncommon (e.g., Huerta, Bishop, Duncan, Hus, & Lord, Reference Huerta, Bishop, Duncan, Hus and Lord2012). In future samples, care will be necessary to separate autism from S(P)CD and to determine whether children with ADHD have comorbid pragmatic language difficulties causing functional impairment sufficient to reach diagnostic criteria for S(P)CD or alternatively, whether the subthreshold pragmatic difficulties are secondary to ADHD symptoms. This approach will enable the field to compare the pragmatic language profiles of children who meet the criteria for ADHD, S(P)CD, autism, and TD children, together with the effects of comorbidity among these diagnostic groups.

Finally, going forward, we would encourage researchers to ensure they provide sufficient data in their research reports to facilitate calculation of effect sizes (if not reported) including means, standard deviations, and subgroup n values, and to provide ready access to raw data to permit secondary data analysis or the combining of data sets. EQUATOR reporting guidelines offer useful recommendations. Furthermore, our risk of bias and quality assessment revealed that future studies would benefit from clearly defined and sufficiently powered samples as well as providing some indication of the validity of their chosen measurement tools.

Conclusions