Hong Kong residents practise a wide variety of religions, including Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity (i.e. Protestantism and Roman Catholicism), Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism, the Baha'i faith and Zoroastrianism.Footnote 1 This diversity of religions can be attributed not only to the British colonization of the city but also to the waves of war and social turmoil in mainland China from 1941 to 1976, during which religious organizations, missionaries and believers fled the mainland to settle in Hong Kong. The diversity and coexistence of religions in Hong Kong continues today despite the transfer of sovereignty in 1997.Footnote 2

Diverse religions have important implications for political and social developments in Hong Kong because religious affiliation affects believers’ attitudes towards the government and towards other people. Different religious affiliations lead to different levels of trust in the government and in people. For instance, according to a study by May Cheng and Siu-lun Wong, before 1997 Catholics and Protestants had the highest levels of distrust of the Chinese government compared to Buddhists and practitioners of Chinese folk religions, while those without religious affiliation displayed average levels of trust.Footnote 3

Religious groups have a history of participating in political activities in the city.Footnote 4 For example, Catholics had a higher voter turnout compared to unaffiliated voters before 1997, and they also expressed a stronger preference for democracy than for supporting the establishment.Footnote 5 Since 1997, religious groups have taken part in influential social movements in the city, including the 2014 Umbrella Movement.Footnote 6 In the early stages of the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (ELAB) Movement, religious groups were involved in mobilizing online petitions against the bill as well as participating in the movement itself, which occurred from June 2019 to February 2020.Footnote 7 What has made religious mobilizations in Hong Kong unique is that “they could generate a peaceful framing for the protest,”Footnote 8 in addition to becoming a medium for cultivating relational ties among their followers.Footnote 9

There have been great socioeconomic and political changes in Hong Kong and in China since 1997 when the sovereignty of the city was handed over to China. Both the Hong Kong government and Beijing have adjusted their policies towards religious groups in Hong Kong,Footnote 10 and “religion [in Hong Kong] is increasingly in Beijing sights.”Footnote 11 Thus, there is a need to reassess the relationship between religious affiliation and believers’ trust in central and local state authorities in the city.

Based on a 2021 survey of 3,744 residents in Hong Kong, we examine how religious affiliation affects people's trust in China's central authorities, the political and civil institutions in Hong Kong, and interpersonal trust. We find that Eastern religions, mainly traditional Chinese religions, have a positive effect on people's trust in state authorities, whereas Western religions have a stronger and positive effect on interpersonal trust. In addition, followers of Western religions are more accepting of unconventional groups and behaviour than followers of Eastern religions. Finally, we find that affiliation with Western religions has no effect on believers’ trust in the political authorities in Beijing and Hong Kong. Our findings help to contextualize the political rationale for the Hong Kong government's policies towards different religions after 1997.

Religion and Trust

Trust improves interpersonal relationships and contributes to cooperation and effective governance. Trust is a central facet of social cohesion and can lead to “a willingness to get involved in our communities,” “higher rates of economic growth,” “satisfaction with government performance,” and an altogether more pleasant daily life.Footnote 12 Trust also helps to achieve order by reducing social complexity,Footnote 13 lowering transaction costs,Footnote 14 serving as “a lubricant for cooperation,”Footnote 15 and facilitating the successful functioning of democratic institutions.Footnote 16 In contrast, a lack of trust creates a highly undesirable living environment because it often leads to selfish behaviour and non-cooperation.Footnote 17

Serving as “an essential component of social capital,” trust facilitates cooperation.Footnote 18 One way of creating and strengthening social capital is to facilitate citizen participation in public affairs as participation “inculcates skills of cooperation as well as a sense of shared responsibility of collective endeavour.”Footnote 19 Another method for stimulating public participation is involvement in a religious community.Footnote 20 Religion can contribute to interpersonal trust partly because many religions incorporate social values and respect for human beings.Footnote 21 For example, existing studies find Protestants to be more trusting than practitioners of other religions because Protestants see humanity as one moral community.Footnote 22

As far as the relationship between religion and political trust is concerned, some studies suggest that religious believers have a high degree of trust or support for the current regime;Footnote 23 others find that the Protestant church encourages its followers to be anti-establishment and to support human rights and democratic values.Footnote 24

In multi-faith Hong Kong, religions and practising folk religions also affect believers’ social and political behaviour.Footnote 25 Researchers find that young people with religious affiliations are more concerned with social and public issues and are more likely to be civically active than their non-religious peers.Footnote 26 Christians also tend to be more accepting of concepts such as forgiveness.Footnote 27 A recent study discovered that churches have an influence over their members’ opinions on social and political issues.Footnote 28

Existing studies on religion in Hong Kong have also noted a relationship between religious affiliation and trust in the government. A 1995 survey of 2,275 residents in Hong Kong found that practitioners of different religions had different degrees of distrust of China's central government.Footnote 29 Of those surveyed, nearly 62 per cent of Catholics, 58.5 per cent of Protestants, 50.2 per cent of Buddhists and 46.3 per cent of folk religion practitioners distrusted or highly distrusted the central government. The higher levels of distrust among believers of Western religions in Hong Kong were attributed to the tight control over religious activities in mainland China during the Cultural Revolution and a concern for the erosion of freedom and autonomy following the transfer of sovereignty in 1997.Footnote 30

There has long existed a relationship between the state and religion in Hong Kong. The government in colonial Hong Kong often requested religious organizations to provide education and social services in the city.Footnote 31 For example, in the early colonial period, over 80 per cent of secondary schools were operated by churches.Footnote 32 During the 1990s, about one-quarter of Hong Kong's school children attended Catholic schools, although 92 per cent of these students were not Catholic. Similarly, as requested by the government, Protestant churches were heavily involved in the development of vocational schools. In return for these services, the government provided land and significant financial subsidies.Footnote 33 It was suggested that some of the churches receiving large amounts of government educational and social subsidies be absorbed by, or become defenders of, the establishment.Footnote 34

Significant socioeconomic and political changes in Hong Kong since 1997 may have affected the relationship between religion and the government.Footnote 35 For example, Protestant churches have gone from being in a cooperative partnership with the government to becoming an advocate for democratic reform and even a critic of the government. The privileged position once given to Christian organizations within education and the social services sector has now been given to Taoist and Buddhist organizations.Footnote 36

There is thus a need to re-examine the relationship between different religious affiliations and believers’ trust in the political authorities and in interpersonal relations. Previous research has not systematically compared the effects of different religions on these types of trust. In this study, we examine how religious affiliation affects believers’ political and social trust in Hong Kong. We find that religious behaviour and practices are common among Hong Kong residents although many do not identify as followers of a religion. We also find that affiliation with Western religions has a stronger positive effect on social and interpersonal trust, whereas belief in Eastern religions has a positive effect on trust in state authorities. In addition, we find that followers of Western religions are more tolerant of unconventional behaviour and of people with different lifestyles.

This study is based on the Hong Kong Political Culture Survey, which we conducted from May to September 2021. In total, we interviewed 3,744 respondents, aged 16 or above, in Hong Kong. Considering geographic location as a potential source of variation in socioeconomic status and latent differences in political attitudes among respondents, we randomly selected 72 electoral districts out of the 452 total districts in Hong Kong. In each district, we interviewed 52 random residents based on demographic data from the 2016 census data, including gender, age, education, income and housing type. Each interview lasted for approximately 30 minutes, and we used tablets to record the answers.

Religions and Religious Practices in Hong Kong

This section reports the religious affiliation and religious activities of Hong Kong residents according to the data collected from our survey. Table 1 compares the findings of three surveys conducted in 1988, 1995 and 2021. Many respondents practised folk religions but did not perceive themselves as having a religious affiliation. We divide respondents who reported no religious affiliation into two groups: (1) those having no religious affiliation but who practised folk religions; and (2) those with no religious affiliation and who did not practise any folk religions. As the number of followers of Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism and other religions was limited, they were included in Eastern religious groups for statistical analysis.Footnote 37

Table 1. The Beliefs of Religious Believers in Hong Kong

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021; Cheng and Wong Reference Cheng, Wong, Lau, Lee, Wan and Wong1997, 301.

According to our survey in 2021, 13.4 per cent of the respondents were Protestants or Catholics, and 20.8 per cent were followers of various Eastern religions. The proportion of followers of Western religions in Hong Kong remained stable from 1998 to 2021, but the number of those with religious affiliations seems to have decreased since 1988. According to the 1988 survey, 58.3 per cent had no religious affiliation – that share increased to 60.2 percent in 1995 and 66 per cent in 2021.

We identified several demographic differences in terms of religious affiliation. Among those surveyed, 46 per cent were male and 54 per cent female. Of the 65.8 per cent of respondents from both genders who identified as having no religion, 33 per cent were male and 32.7 per cent female, showing no gendered difference. Female respondents were more likely to follow Eastern religions (Table 2).

Table 2. Religious Believers by Gender

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

As presented in Table 3, people under 25 had the largest share of respondents with “no religion and no religious practices” (28.4 per cent). In contrast, people aged 45 or older had the smallest portion of “no religion and no religious practices” (i.e. less than 5 per cent). Of the respondents who claimed religious affiliation, those aged between 16 and 44 were more likely to follow Western religions, whereas people aged 45 or older were more likely to be followers of Eastern religions.

Table 3. Religious Believers by Age (%)

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

There is a commonality across different religions in terms of their views about life and death. According to our survey (Table 4), more than 70 per cent of the respondents reported that “it is good to be worshipped by posterity after death” and 49.8 per cent reported that “the soul survives after death.”Footnote 38 For example, burning incense is one of the most common traditions in Chinese society performed in memory of loved ones who have died. During the Qingming Festival (Ancestors’ Day), families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean the gravesites, pray to their ancestors and make ritual offerings. According to a 1995 survey of 2,275 residents in Hong Kong, 55.2 per cent practised ancestor worship.Footnote 39 Our survey shows that that nearly 75 per cent of the respondents had burned incense for family members who had passed away.

Table 4. Religious Beliefs and Practices in Hong Kong

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

Note: Respondents could provide more than one answer.

In this vein, Hong Kong residents regularly organize temple festivals to celebrate the birthdays of their patron deities, visit temples to seek the deities’ blessings, attend church services, burn incense, worship ancestors, participate in fortune telling and follow fengshui 风水 rules.Footnote 40 Many Hong Kong residents who reported engaging in these practices did not identify themselves as belonging to a particular religion.Footnote 41 In our survey, nearly 66 per cent reported that they were not affiliated with any organized religion, while about 34 per cent reported a religious affiliation. About 56 per cent of the respondents considered themselves to be non-religious but practised at least one of the above-mentioned folk religious activities; nearly 10 per cent were not religious believers and did not practice any folk religion.

The religious activities and preferences of Hong Kong residents may have to do with traditional practices. In Chinese culture, it is believed that no matter how skilful and dedicated an individual may be, there are independent factors involved in determining success: destiny and human effort are both important. Some people believe that complying with fengshui practices puts individuals in harmony with their environment and can help them to lead a better life or achieve success.Footnote 42 According to our survey, more than 46 per cent of the respondents agreed that fengshui should be considered first when buying an apartment. Similarly, 70.4 per cent reported that they would select an auspicious day for a joyous occasion, funeral, celebration of a business opening or a home relocation. Fortune telling is also a common practice associated with destiny and effort. Over 40 per cent of the respondents noted that they had taken part in drawing a fortune stick. Thus, although some people did not identify themselves as followers of Buddhism or Taoism, they accepted some practices based on shared cultural beliefs.

Trust in Hong Kong: A Description

Our survey included questions about Hong Kong residents’ trust in state authorities, social institutions and other people. We group respondents’ trust in individuals and social institutions as social trust, and we treat trust in state authorities as political trust.Footnote 43 We further divide trust in political authorities into trust in central authorities and trust in Hong Kong authorities.

Trust in political authorities

The 2021 survey asked questions about public trust in political authorities in Beijing and Hong Kong. National authorities include the Chinese government, the National People's Congress (NPC), the Chinese courts, the central government's agencies in Hong Kong, and the Chinese military stationed in Hong Kong (PLA). The level of trust is divided into four categories: highly trust, relatively trust, relatively distrust and highly distrust.

As presented in Table 5, levels of trust in each of these authorities range from 50 per cent to 52 per cent.Footnote 44 Hong Kong residents’ levels of trust in the political authorities stand in contrast to their mainland counterparts’ trust in the Chinese central authority. Various surveys in China show that mainland Chinese have a much higher level of trust in the Chinese central authority, ranging from 70 to 90 per cent.Footnote 45 One possible reason for the difference between Hong Kong residents and their mainland counterparts is that information control in Hong Kong is not as strict as it is in the mainland.

Table 5. Trust in Political Institutions

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

Note: Respondents could provide more than one answer.

We also asked respondents about their trust in five local political institutions: the Hong Kong police, Hong Kong's current political system, the Special Administrative Region (SAR) government, the Legislative Council and the courts. Table 5 presents Hong Kong residents’ trust in these institutions. The level of trust in Hong Kong authorities is generally higher than trust in central authorities, ranging from 49 per cent for the Hong Kong police to 64 per cent for the courts. The lowest level of trust was for the Hong Kong police, which likely results from the police handling of the 2019 Anti-ELAB Movement.Footnote 46 In contrast, the respondents had the highest level of trust in the courts, which may reflect that the residents still had trust in the court system despite the political turmoil in 2019.

Our survey results show a small difference between Hong Kong residents’ trust in the national authorities and their trust in the Hong Kong authorities. Overall, Hong Kong residents’ trust in local authorities is slightly higher than their trust in the national authorities, and their trust in the Hong Kong courts (64 per cent) is much higher than their trust in Chinese courts (52 per cent). Their trust in Hong Kong's Legislative Council (53 per cent) mirrors their trust in the NPC (51 per cent). Finally, Hong Kong residents displayed a similar level of trust in the SAR government (52 per cent) and the national government (51 per cent).

It must be noted, however, that the survey was conducted in 2021, after the National Security Law (NSL) took effect in July 2020. The timing might have caused inaccuracies in our data as some respondents would have been reluctant to truthfully share their views on issues with political implications. To counter this issue, we informed respondents that the survey would be used purely for academic purposes and their private information would not be disclosed to any other party. Their names were not collected, and their home addresses were not recorded.

Before and after the NSL came into effect, social media posts about the law, including those posted on anonymous platforms, were divided. Positive and neutral messages far outnumbered critical messages across social media platforms regardless of whether a media platform allowed for a high degree of anonymity or not.Footnote 47 The law may not always deter people from expressing their true views; however, the effect of the law on people's willingness to express their views requires further research.

Social trust

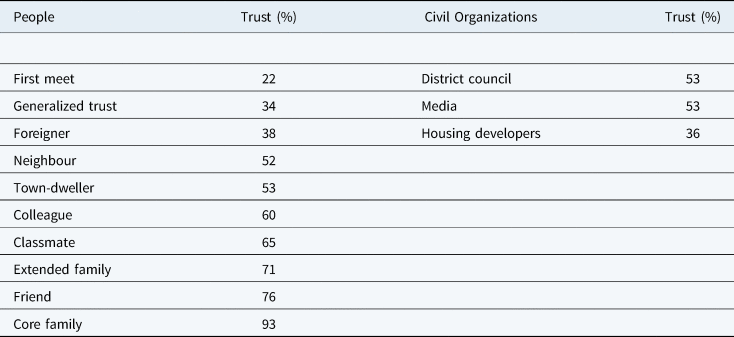

Our survey also covered questions concerning Hong Kong residents’ trust in civil organizations, including the district council, the Hong Kong media and housing developers. The district council is a de facto institution intended to improve community governance and welfare, advise the city government on district affairs, promote recreational and cultural activities, and facilitate environmental improvements within a district. Members of this council are selected through election or appointment. Thus, this council is not a political organization that exerts traditional political power. Next, most media in Hong Kong are owned by private actors and not the government. Finally, housing developers hold a lot of sway in a city that depends on real estate.

As presented in Table 6, Hong Kong residents’ trust in the district council is 53 per cent, which is the same as their trust in the Legislative Council and in local media. Finally, there is a low level of trust in housing developers in Hong Kong (36 per cent), who residents believed benefited greatly from the city's past economic boomtimes at the expense of residents.

Table 6. Social Trust in Hong Kong

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

Note: Respondents could provide more than one answer.

Our survey also included questions that measured interpersonal trust in Hong Kong. Table 6 presents the respondents’ trust in different groups of people. Not surprisingly, the respondents have the lowest level of trust in people they meet for the first time (22 per cent) and the highest level of trust in core family members (93 per cent).

Religion and Trust: Empirical Analysis

In this section, we analyse the effect of religious affiliation on three types of trust: in central authorities, in Hong Kong authorities and in social institutions. For analytical purposes, these three dependent variables of trust are factor indexes. Trust in the central authorities comprises five institutions, listed in Table 5; trust in Hong Kong authorities includes five institutions also listed in Table 5; trust in social institutions includes the three civil organizations presented in Table 6.

Independent variables

We divide respondents’ religious affiliations into four categories as explanatory variables: (1) having no religious affiliation but practising folk religions; (2) Eastern religious affiliation; (3) Western religious affiliation; and (4) no religious affiliation and no practising of folk religions (Table 1). We also include seven control variables: age, education, gender, marital status, social class, ethnic identity and media accessed by the respondents.

Age is divided into four categories: 16–24, 25–44, 45–65, and 65 or older. Education has five levels: primary and lower, lower secondary, upper secondary, sub-college degree, and college degree and higher. Gender is a dummy variable, with male coded as “0.” Marital status is also a dummy variable, with married coded as “1.” Social class has five categories: upper, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, and lower.Footnote 48 Ethnic identity is a categorical variable of four categories: Hongkonger, Chinese, Chinese Hongkonger, and foreigner.

We also measure the respondents’ political orientation by including their media usage. Specifically, we measure political orientation by the respondents’ reported frequency of readership of Apple Daily, the most prominent media outlet critical of the government in the city. The newspaper had more than 3.8 million registered web users, which is equivalent to half of Hong Kong's population, and 630,000 e-subscribers before it was shut down in 2021. There are six options – never, monthly, weekly, several times a week, daily, and several times a day – and answers are coded on a zero-to-one scale.

Trust in political and social institutions

Table 7 presents the results of multilevel OLS regressions.Footnote 49 Belief in an Eastern religion has a significant and positive effect on trust in central authorities, the local political system and social institutions. Belief in a Western religion has a positive and significant effect on trust in social institutions, but not on trust in the central authorities or the local political system. This finding is in line with research that shows that Eastern religions, including Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, act as “state defenders,” legitimizing government decisions.Footnote 50 In contrast, Western religious organizations, including Catholic and Protestant churches and groups, become “state critics” to promote political justice.Footnote 51 Those who do not have any religious affiliation and who do not practise folk religions tend not to trust central authorities or Hong Kong's political system.

Table 7. Religion and Trust in Institutions

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

Notes: The factor indexes of trust in central authorities, in the Hong Kong political system and in social institutions were created through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The variance of each factor is higher than 0.5 and statistically significant, which is the acceptable threshold of variance (Awang 2014). *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

In terms of age, people aged 16–24 and those aged 25–44 lack trust in the local political system. Higher education tends to have a negative effect on trust in the central authorities. People with a college degree or higher education lack trust in the central authorities, local political system and social institutions. Gender does not have a significant effect, whereas marriage has a positive effect on trust in central authorities and a negative effect on trust in civil society.

Being lower-middle class, middle class or upper-middle class has a significant and positive effect on people's trust in central authorities and in the local political system. Belonging to the upper class has a negative but weak effect on trust in the central authorities. Belonging to the lower-middle class has a negative effect on trust in social institutions, whereas upper-middle class status has a positive effect on trust in social institutions.

Overall, social class status demonstrates an inverted-U shape. Both the lowest and highest classes have the least trust in institutions. The middle classes, including the lower-middle, middle and upper-middle classes, are more trusting of institutions overall. The distrust among the lower classes may reflect the increasing income gap in Hong Kong society, whereas a lack of trust among the upper class may reflect the limited subsidies they receive from the government.

Identity has a positive effect on trust in central authorities and the local political system. Those who self-identified as Hongkongers are less trusting of national and local institutions. Meanwhile, those who self-identified as Chinese are less trusting of civil society compared to Hongkongers. We conducted another analysis by relacing ethnic identity with ethnicity (i.e. Chinese, East Asian, South-East Asian, White and others). The effect of religion on trust in central authorities, the Hong Kong system and civil society remains the same. Moreover, compared with Chinese, white people have less trust in the central authorities and the Hong Kong system, whereas East and South Asians are more likely to trust the Hong Kong system and civil society but not the central authorities.

Finally, reading Apple Daily has a significant but negative effect on trust in the central authorities, the Hong Kong system and civil society. For a unit of increase in readership frequency, there is about a 30 per cent decrease in the level of trust in central authorities, a 19 per cent drop in trust in the Hong Kong political system and a 4 per cent drop in the trust in Hong Kong civil society.

To sum up, affiliation with Eastern or Western religions exhibits a different effect on the trust in political authorities. Highly educated people (college degree holders and above) are also less likely to trust the political authorities.

Religion and social attitudes

Religious affiliation may also affect individuals’ attitude to other people in society. Religions often incorporate values of social solidarity, which contributes to believers’ trust in other people.Footnote 52 Previous studies argue that the intrinsic values of religion that emphasize love, brotherhood and compassion increases tolerance.Footnote 53 Different religions also have varying degrees of tolerance towards unconventional behaviour and cultural differences. Research on the relationship between religion and forgiveness in Hong Kong has shown that practitioners of Christianity have more positive concepts of forgiveness.Footnote 54

In this section, we examine how religious affiliation affects believers’ attitudes towards four types of people: (1) people with whom a respondent has had much contact; (2) people with whom a respondent has not had much contact; (3) marginalized groups; and (4) selected groups with different lifestyles or ethnic backgrounds.

The first group includes four types of people with whom the respondent has had close contact (classmates, extended family, friends and core family members), and the second group includes the remaining six types (Table 6). The third group (marginalized or unconventional groups) includes four types of people: drug users, alcoholics, gay people and people living with HIV/AIDS. The fourth group (selected groups) includes three types of people: unmarried cohabitants, people of different ethnic identities and foreign domestic helpers working in Hong Kong. We asked respondents: “To what extent do you accept the following people as your friends?” We gave them a choice of four answers: completely acceptable, relatively acceptable, relatively unacceptable or completely unacceptable.

These four dependent variables are factor indexes created through exploratory and confirmatory analyses, ranging from zero to one. Our analysis aims to show whether a religious affiliation affects interpersonal trust and a surveyed respondent's tolerance of the third and fourth groups.

In addition to religious belief or the main explanatory variable, we used the same sets of control variables – age, education, gender, marital status, social class and ethnic identity – but excluded the political orientation variable (i.e. Apple Daily).

The statistical results are reported in Table 8. Both Eastern and Western religions have a positive effect on trust in people in close or in less close contact. People who did not have a religious belief and did not practise folk religions did not trust people with whom they have close or less close contact.

Table 8. Religion and Interpersonal Trust

Source: Authors’ Hong Kong Political Culture Survey 2021.

Notes: The four dependent variables are factor indexes. The variance of each factor is higher than 0.5 and statistically significant, which is the acceptable threshold of variance (Awang 2014). *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Young people (aged 16–24) are less likely to trust people with whom they have close contact. Educational attainment, except lower secondary education, increases respondents’ trust in people with whom they have close contact, but not in those with whom they have less contact. Compared with males, females are more likely to trust those with whom they have close or less close contact. Marriage has a negative effect on trusting those with whom respondents have close and less close contact.

Class status has a different effect on trust in people with whom there is close contact. Upper-middle class status and upper-class status both have a positive effect on such trust, but lower-middle class status has a negative effect. Middle class status and upper-middle class status both exert a positive effect on trust in people with whom respondents have less contact.

Finally, with regard to ethnic identity, Chinese ethnicity has a positive effect on trust in people with whom respondents have close contact, whereas identifying as Chinese, Chinese Hongkonger or foreigner has a positive effect on trust in people with whom there is less contact.

As far as the relationship between religious affiliation and tolerance of the marginalized and selected groups is concerned, belief in an Eastern religion does not increase a person's tolerance of the selected groups, but it has a positive effect on tolerance of the marginalized groups. In contrast, belief in a Western religion has a strong positive effect on tolerance of both types of groups.

Compared with people aged 65 or older, all age groups seem to tolerate the selected groups. Belonging to the 25–44 or the 45–64 group has a significant and positive effect on tolerating the marginalized groups. This finding seems to suggest that Hong Kong is an open society.

Education has a positive and significant effect on the acceptance of both types of groups, except for lower secondary education. The higher the education level, the stronger the effect. Lower secondary education has a positive effect on tolerance of the selected groups but not of the marginalized groups.

Being a woman has a negative effect on tolerating the marginalized groups. Married people are also less likely to tolerate both types of groups. This may not be surprising given that some unconventional behaviour can contradict family values. Middle class status and upper-middle class status both have a negative effect on tolerance of the marginalized groups.

Both Chinese and foreign identity have a positive effect on the tolerance of selected groups. Only Chinese Hongkonger identity has a positive and significant effect on tolerance of the marginalized, whereas being a foreigner has a negative effect on tolerating the marginalized.

To sum up, practitioners of Western religions appear to be tolerant of marginalized groups and selected groups. This finding is in line with prior research on the effect of Western religions, which often view people as belonging to one moral community.Footnote 55 Moreover, education is a consistent factor that affects the acceptance of unconventional behaviour and selected groups.

Conclusion

As a global city, Hong Kong has a long tradition of religious coexistence, but there have been changes in religious affiliations. According to existing surveys, the proportion of people in the city who claim to have no religious beliefs increased from 59.3 per cent in 1988 to 60.2 per cent in 1995 and to 65.8 per cent in 2021. However, although many residents in Hong Kong do not self-identify as following any religion, many of them engage in practices connected to folk religions. For example, fengshui continues to play an important role in people's daily life, alongside fortune telling.

We find that different religious affiliations have different effects on believers’ trust in political and social institutions and in interpersonal relations. Overall, affiliation with an Eastern religion increases trust in the Chinese central government and the Hong Kong government. Such an affiliation moderately increases acceptance of marginalized groups, but not those selected groups with different lifestyles. In contrast, affiliation with a Western religion does not increase trust in the political authorities, but neither does it reduce trust. This affiliation, however, increases one's trust in civil institutions and enhances acceptance of both marginalized groups and selected groups. This may have to do with the emphasis in many Western religions on respect for individuals as members of a moral community.Footnote 56

The Hong Kong government seems to be cognizant of the relationship between religious affiliation and practitioners’ views of the government, and government policies have reflected the changing attitudes towards different religions.Footnote 57 Since 1997, collaboration between the city government and Western religious organizations has decreased, whereas the government's cooperation with Eastern religious organizations has increased.Footnote 58

Since 1997, the Hong Kong government has put an end to the dominance of Western religion in daily events by, for example, granting Chinese temples the same wedding ceremony licence as was previously held only by churches and introducing Buddha's birthday as a new public holiday.Footnote 59 Churches no longer have such a dominant role in providing education in Hong Kong, as non-faith-based schools and Eastern religious schools now also partner with the government in the provision of education.Footnote 60 The government has also undermined the direct control of churches over schools by democratizing the formation of school management committees with the introduction of the school-based management system.Footnote 61

Owing to the changing political environment in Hong Kong, it is likely that the city government and Beijing will continue to favour Eastern religions and Chinese folk religions. As more residents in Hong Kong, especially younger people, do not belong to any organized religion, it remains to be seen whether the current political environment will affect the number of religious worshippers, especially those who follow Western religions. Future research could examine the political and social consequences of the changing relationship between the government and different religious affiliations in the city.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a General Research Fund (Number: 16601820) and the Anti-Epidemic Fund 2.0 of the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong government.

Competing interests

None.

Yongshun CAI is professor of social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. His research interests include governance in China and Hong Kong society.

Sin Yu HUNG is a research assistant in the Division of Social Science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her research interests focus on Hong Kong society.